- See Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.

| Amenemhat III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammenemes III, Ameres, Lamares, Moeris | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Statue of Amenemhat III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 40 + x according to the Turin Canon but at least 45 years, in the 19th and 18th centuries BC.[1][lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Senusret III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Amenemhat IV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Aat, Khenemetneferhedjet III, Hetepti (?) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Neferuptah, Amenemhat IV (probably), Sobekneferu (probably), Hathorhotep (?), Nubhotep (?), Sithathor (?) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Senusret III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid at Hawara | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid at Dahshur | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amenemhat III (Ancient Egyptian: Ỉmn-m-hꜣt meaning 'Amun is at the forefront'), also known as Amenemhet III, was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the sixth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. He was elevated to throne as co-regent by his father Senusret III, with whom he shared the throne as the active king for twenty years. During his reign, Egypt attained its cultural and economic zenith of the Middle Kingdom.

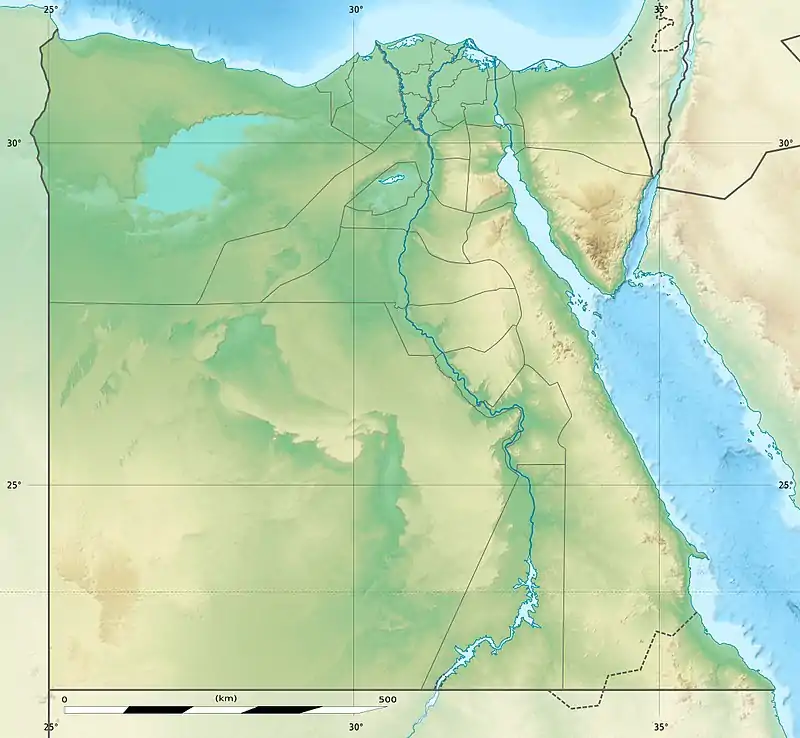

The aggressive military and domestic policies of Senusret III, which re-subjugated Nubia and wrested power from the nomarchs, allowed Amenemhat III to inherit a stable and peaceful Egypt. He directed his efforts towards an extensive building program with particular focus on Faiyum. Here he dedicated a temple to Sobek, a chapel to Renenutet, erected two colossal statues of himself in Biahmu, and contributed to excavation of Lake Moeris. He built for himself two pyramids at Dahshur and Hawara, becoming the first pharaoh since Sneferu in the Fourth Dynasty to build more than one. Near to his Hawara pyramid is a pyramid for his daughter Neferuptah. To acquire resources for the building program, Amenemhat III exploited the quarries of Egypt and the Sinai for turquoise and copper. Other exploited sites includes the schist quarries at Wadi Hammamat, amethyst from Wadi el-Hudi, fine limestone from Tura, alabaster from Hatnub, red granite from Aswan, and diorite from Nubia. A large corpus of inscriptions attest to the activities at these sites, particularly at Serabit el-Khadim. There is scant evidence of military expeditions during his reign, though a small one is attested at Kumma in his ninth regnal year. He also sent a handful of expeditions to Punt.

Amenemhat III reigned for at least 45 years, though a papyrus fragment from El-Lahun mentioning a 46th year probably dates to his reign as well. Toward the end of his reign he instituted a co-regency with Amenemhat IV, as recorded in a rock inscription from Semna in Nubia, which equates regnal year 1 of Amenemhat IV to regnal year 44 or 46–48 of Amenemhat III. Sobekneferu later succeeded Amenemhat IV as the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty.

Sources

Contemporaneous sources

There are a variety of contemporary sources attesting to the reign of Amenemhat III. Chief among these are the collection of inscriptions left at mining sites throughout Egypt, Nubia, and the Sinai peninsula.[13] His activities in the Sinai are particularly well attested to, spanning regnal years 2 to 45.[14][15] It is notable though, that the overwhelming majority of these inscriptions originate outside Egypt.[16] He is also well attested to through his statuary with approximately 80 works attributed to him,[17][16] his building program, particularly concentrated around Faiyum, and the two pyramids that he had built.[14][15] The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus – one of a limited set of evidence attesting to Egyptian knowledge of mathematics[18] – is also thought to have been originally composed during Amenemhat III's time.[19]

Historical sources

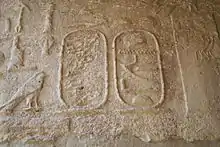

The Karnak king list from the Festival Hall of Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BC)[10] has a lacuna of two entries between Amenemhat II and Amenemhat IV, though three kings are known to have reigned during this period – Senusret II, Senusret III, and Amenemhat III.[20] In the Abydos king list from the temple of Seti I (c. 1290–1279 BC)[21] in Abydos, Amenemhat III is attested by his praenomen Ni-maat-re in the sixty-fourth entry.[22] His praenomen also occupies the sixty-fourth entry in the king list at the temple of Ramesses II (c. 1279–1213 BC)[21] in Abydos.[23] In the Saqqara Tablet from the tomb of the chief lector priest and chief of works Tjuneroy, Amenemhat III's praenomen occupies the twentieth entry.[24][25] The Turin Canon has a lacuna in the mid-Twelfth Dynasty preserving no names and only partial reign lengths. The twenty-fifth entry of the fifth column corresponding to Amenemhat III preserves only a regnal length of 40+x years.[1][26][27] The entries of his presumed children and immediate successors – Amenemhat IV and Sobekneferu – are near-wholly intact preserving their praenomen and reign lengths.[1][27]

Amenemhat III is also mentioned in Manetho's Aegyptiaca, originally composed circa the 3rd century BC, tentatively dated to the reign of Ptolemy II.[28][29][30] The original work is no longer extant, but has persisted through the writings of Josephus, Africanus, Eusebius, and Syncellus.[31] He is accorded a reign of 8 years under the name Λαχάρης (romanized Lacharês / Lamarês) by both Africanus and Eusebius.[32] Syncellus accords him a reign of 43 years under the name Μάρης (romanized Marês) as the thirty-fifth king of Thebes.[33][lower-alpha 2]

Family

.jpg.webp)

Amenemhat III was the son of Senusret III, his predecessor on the throne.[4] There is no explicit testimony to this filial relationship, however, the inference can be made from their co-regency.[35] The identity of his mother is unknown.[36] He had several sisters – Menet, Mereret, Senetsenbetes, Sithathor, and a partially known Khnemet-.[37]

Two of Amenemhat III's wives are known, Aat and Khenemetneferhedjet III, who were both buried in his Pyramid at Dahshur.[38][39] Hetepti – the mother of Amenemhat IV – might be another wife.[36] He had one confirmed daughter, Neferuptah, who appears to have been groomed as his successor, owing to her name being enclosed in cartouche.[40] The Egyptologists Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton indicate that Neferuptah was originally buried at Amenemhat III's second pyramid at Hawara but was eventually moved to her own pyramid after an early death.[40] The Egyptologist Wolfram Grajetzki contradicts this stating that she was never buried in Hawara, but had possibly outlived her father and was buried elsewhere as a result.[36] Two other children, both of whom reigned as king, are also attributed to Amenemhat III: a son, Amenemhat IV and a daughter, Sobekneferu.[41] It has also been suggested that Amenemhat IV may instead have been a grandson.[42] Evidence of burials of three other princesses – Hathorhotep, Nubhotep, and Sithathor – were found at the Dahshur complex, but it is not clear whether these princesses were Amenemhat III's daughters as the complex was used for royal burials throughout the Thirteenth Dynasty.[43]

Reign

Chronology

The relative chronology of rulers in the Twelfth Dynasty is considered settled.[44] The Ramesside king lists and the Turin Canon are a significant source in determining the relative chronology of the rulers.[45] The Turin Canon has a lacuna of four lines between Amenemhat I and Amenemhat IV, recording only partial regnal lengths for the four kings – 10+x, 19, 30+x, and 40+x years respectively.[27][46] The king lists of Seti I and Ramesses II at Abydos and the Saqqara tablet each list Amenemhat III with Senusret III – whose praenomen is Kha-kau-re[11] – as his predecessor and Amenemhat IV – whose praenomen is Maa-kheru-re[11] – as his successor.[47][48][49] Instead Egyptological debate has centred on the existence of co-regencies.[44]

Co-regency

In his twentieth regnal year, Senusret III elevated his son Amenemhat III to the status of co-regent.[50] The co-regency seems to be established from several indicators,[lower-alpha 3] though not all scholars agree and some[lower-alpha 4] instead argue for sole reigns for both kings.[58] For the following twenty years, Senusret III and Amenemhat III shared the throne, with Amenemhat III taking the active role as king.[59][4][60] It is assumed that Amenemhat III took the primary role as the regnal dates roll over from year 19 of Senusret III to year 1 of Amenemhat III.[60][59] His reign is attested for at least 45 years, though a papyrus fragment from El-Lahun mentioning 'regnal year 46, month 1 of akhet, day 22' probably dates to his rule as well,[59][61] since the village was founded by Amenemhat III's grandfather, Senusret II, and no other Twelfth Dynasty ruler after Senusret II reigned for more than 40 years. The highest date might be found on a bowl from Elephantine bearing regnal year 46, month 3 of peret. This attribution is favoured by the Egyptologist Cornelius von Pilgrim, but rejected by the Egyptologist Wolfram Grajetzki who places it in the early Middle Kingdom.[62] In his 30th regnal year, Amenemhat III celebrated his Sed festival which is mentioned in several inscriptions.[63] His reign ends with a brief co-regency with his successor Amenemhat IV.[59][64] This is evidenced from a rock inscription at Semna which equates regnal year 1 of Amenemhat IV with regnal year 44 or perhaps 46–48 of Amenemhat III.[59][65][66]

These two kings – Senusret III and Amenemhat III – presided over the golden age of the Middle Kingdom. Senusret III had pursued aggressive military action to curb incursions from tribes people from Nubia.[4][67] These campaigns were conducted across several years and were brutal against the native populations, including slaughter of men, enslavement of women and children, and the burning of fields.[68] He also sent a military expedition into Syria-Palestine, enemies of Egypt since the reign of Senusret I.[67][69] His internal policies targeted the increasing power of provincial governors, transferring power back to the reigning monarch.[70][4] It is disputed whether he dismantled the nomarchical system.[69] Senusret III also formed the basis for the legendary character Sesostris described by Manetho and Herodotus.[71][68] As a consequence of Senusret III's administrative and military policies, Amenemhat III inherited a peaceful and stable Egypt,[4] which reached its cultural and economic zenith under his direction.[64][9][16]

Military campaigns

There is very little evidence for military expeditions during Amenemhat III's reign. One rock inscription records a small mission in regnal year nine. It was found in Nubia, near the fortress of Kumma. The short text reports that a military mission was guided by the mouth of Nekhen Zamonth who states that he went north with a small troop and that there were no deaths on the return south.[72] There is a stela dated to regnal 33 that was discovered at Kerma, south of the Third Cataract, discussing the construction of a wall, though this stela must have originated elsewhere as Kerma was beyond Egypt's control at this time.[63]

Mining expeditions

Exploitation of the quarries of Egypt and the Sinai for turquoise and copper peaked during his reign.[64] A collection of more than 50 texts were inscribed at Serabit el-Khadim, Wadi Maghara, and Wadi Nasb.[64][14] The efforts here were so extensive that near-permanent settlements formed around them.[64][73] The quarries at Wadi Hammamat (schist), Wadi el-Hudi (amethyst), Tura (limestone), Hatnub (alabaster), Aswan (red granite) and throughout Nubia (diorite) were all also exploited.[64][74][75] These all translated into an extensive building program, particularly in the development of Faiyum.[64][73]

Sinai peninsula

Amenemhat III's activities in the Sinai peninsula are well-attested.[64][14] There were expeditions to Wadi Maghara in regnal years 2, 30, and 41–43, with one further expedition in an indiscernible 20 + x year.[76] The temple of Hathor was decorated during the expedition in year 2, which is also the only expedition for which the mining of copper is attested.[77] A related inscription found in Ayn Soukhna suggests that the mission originated from Memphis and perhaps crossed the Red Sea to the peninsula by boat.[78] A single expedition in Wadi Nasb is attested to his 20th regnal year.[79] Between 18 and 20 expeditions to Serabit el-Khadim have been attested to Amenemhat III's reign:[80] in years 2, 4–8, 13, 15, 20, 23, 25, 27, 30, 38, 40, 44, possibly also 18, 29, and 45, alongside a 10 + x and x + 17 years, and there are many inscriptions whose date is indeterminable.[81]

Egypt

One inscription dating to year 43 of Amenemhat III's reign comes from Tura and refers to the quarrying of limestone there for a mortuary temple, either that at Dahshur or Hawara.[82] A stela retrieved from the massif of Gebel Zeit, 50 km (31 mi) south of Ras Ghareb, on the Red Sea coast shows activity at the Galena mines there. The stela bears a partial date suggesting that it was inscribed after regnal year 10.[83][84]

Several expeditions to Wadi Hammamat where schist was quarried were recorded.[64][85] These date to regnal years 2, 3, 19, 20 and 33.[85] Three inscriptions from year 19 note the workforce of labourers and soldiers employed and the outcome of the efforts resulting in ten 2.6 m (8.5 ft) tall seated statues of the king being made. The statues were destined for the Labyrinth at Hawara.[82][86] A few expeditions were sent to Wadi el-Hudi, south-east of Aswan, at the southern border of Egypt, where amethyst was collected. These enterprises date to regnal years 1, 11, 20, and 28.[87][88][89] An expedition was also sent to Wadi Abu Agag, near Aswan, in regnal year 13.[90]

Nubia

North-west of Abu Simbel and west of Lake Nasser lie the quarries of Gebel el-Asr in Lower Nubia. The site is best known as the source of diorite for six of Khafre's seated statues. The locale was also a source of gneiss and chalcedony in the Middle Kingdom.[91] The Chalcedony deposits are also known as 'stela ridge' as it was a place where commemorative stelae and votive offerings were left.[92] Nine of these commemorative objects date to the reign of Amenemhat III, specifically regnal years 2 and 4.[93]

Trade expeditions

A stela was discovered at Mersa on the Red Sea coast, by Rosanna Pirelli in 2005 that detailed an expedition to Punt during the reign of Amenemhat III. The expedition was organized by chief steward Senbef. Under his direction, two contingents were formed. The first was led by an Amenhotep and bound for Punt to acquire incense. The second led by a Nebesu was sent to the mines referred to as Bia-Punt to procure exotic metals.[94][95] There were a total of between two and five expeditions organized during Amenemhat III's rule.[96] Two of the stelae recovered from the site are dated indicating activity there in his 23rd and 41st regnal years.[97]

Building program

Amenemhat III's building program included monuments in Khatana, Tell el-Yahudiyya, and Bubastis.[4] At Bubastis, Amenemhat III probably built a palace which hosts relief art containing his name. Of note is a relief that depicts Amenemhat III officiating his sed-festival.[13] Further works include the enlargement of the temples to Hathor at Serabit el-Khadim and Ptah in Memphis, the construction of a temple in Quban, and the reinforcement of fortresses at Semna.[64][9] At Elephantine a fragment of stela bearing a building inscription was found dated to his regnal year 44. A very similar inscription from possibly the same year was found at Elkab, which indicates the extension of a defensive wall built by Senusret II. Another find at Elephantine was a door lintel of the Eleventh Dynasty, where Amenemhat III added an inscription dated to his regnal year 34. Inscriptions with the king's name have also been uncovered at Lisht, Memphis, and Heracleopolis and statues of the king were found in Thebes.[13] No site, however, received as much attention as Faiyum, with which Amenemhat III is most closely associated.[64][4]

In Faiyum, Amenemhat built a huge temple dedicated to Sobek at Kiman Faras.[9][16] He dedicated a chapel to Renenutet at Medinet Madi.[64] This small temple with three chapels is the best preserved of his temple works. It was built toward the end of his reign and completed by his successor, Amenemhat IV.[13] In Biahmu, he built a massive structure with two colossal 12 m (39 ft) tall seated quartzite statues of himself.[98][73][4] These face Lake Moeris, for which he is credited with excavating, although how much of this work was conducted by Amenemhat III is unknown.[73][4] The work on Lake Moeris had been inaugurated by Senusret II to link the Faiyum Depression with Bahr Yussef.[99] This project reclaimed land downstream at the edges of Lake Moeris allowing it to be farmed.[100] A naturally formed valley 16 km (9.9 mi) long and 1.5 km (0.93 mi) wide was converted into a canal to link the depression with Bahr Yussef. The canal was cut to a depth of 5 m (16 ft) and given sloped banks at a ratio of 1:10 and an average inclination of 0.01° along its length.[101] It is known as Mer-Wer or the Great Canal.[102] The area continued to be used until 230 BC when the Lahun branch of the Nile silted up.[103] Amenemhat III kept close watch on the inundation levels of the Nile, as demonstrated by inscriptions left at Kumma and Semna. The Nile level peaked in his regnal year 30 at 5.1 m (17 ft), but was followed by a dramatic decline so that it measured 0.5 m (1.6 ft) by regnal year 40.[74] The most enduring of his works are the two pyramids that he built for himself,[64] the first king since Sneferu in the Fourth Dynasty to build more than one.[104] His pyramids are in Dahshur and Hawara.[64][105]

Inscriptions by Amenemhat III in the chapel of Renenutet

Inscriptions by Amenemhat III in the chapel of Renenutet Limestone recumbent lion statue at the temple in Medinet Madi

Limestone recumbent lion statue at the temple in Medinet Madi

Pyramids

Dahshur

The construction of the pyramid at Dahshur, the 'Black Pyramid' (Egyptian language: Sḫm Ỉmn-m-hꜣt meaning 'Amenemhat is Mighty'[106] or Nfr Ỉmn-m-hꜣt meaning 'Amenemhat is Beautiful'[107]/'Perfect One of Amenemhat'[108]) began in the first year of Amenemhat III's reign.[106][109] The pyramid core was constructed entirely of mudbrick and stabilized through the building of a stepped core rather than with a stone framework.[110][109] The structure was then encased by 5 m (16 ft; 9.5 cu) thick, fine white Tura limestone blocks held together by wooden dove-tail pegs.[110] The pyramid was given a base length of 105 metres (344 ft; 200 cu) that was inclined towards the apex at between 54°30′ to 57°15′50″ reaching a height of 75 m (246 ft; 143 cu) for a total volume of 274,625 m3 (9,698,300 cu ft).[111][112] The apogee of the structure was crowned, seemingly, by a grey granite pyramidion 1.3 m (4.3 ft) high.[113] This now resides in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, catalogued as JE 35133.[114] The pyramidion had a band of hieroglyphic text running on all four of its sides.[115] That the name of Amun has been erased on the pyramidion can only be the result of Akhenaten's proscription against the god.[114]

In front of the pyramid, lay a mortuary temple of simple design comprising an offering hall and an open columned courtyard. Surrounding the complex were two mudbrick enclosing walls. From the mortuary temple an open, mudbrick walled causeway led to the valley temple.[116] Beneath the pyramid was built a substructure with an intricate series of passages and chambers, with burial chambers for the king and two queens.[117][114] The two queens, Aat and an unidentified queen, were buried here and their remains were recovered from their chambers.[118][115] The king, though, was not buried here.[119] Shortly after the completion of the pyramid superstructure, in around Amenemhat III's 15th regnal year, the substructure began to buckle with cracks appearing inside as a result of groundwater seepage.[119][120] Rushed efforts were made to prevent the structure collapsing, which were successful, but just as Sneferu had decided to do with his Bent Pyramid, Amenemhat III chose to build a new one.[120]

Hawara

The second pyramid is at Hawara (Egyptian language: Uncertain, possibly ꜥnḫ Ỉmn-m-hꜣt 'Amenemhat Lives'[120]), in the Faiyum Oasis.[121] This pyramid project was begun around Amenemhat III's 15th regnal year, after problems with the Dahshur pyramid persisted.[36][120] The choice of Hawara suggests that the cultivation of Faiyum was complete and that Amenemhat III was diverting resources to that area.[122] The pyramid had a core constructed entirely of mudbrick encased in fine white Tura limestone.[123][120] The pyramid had a base length of between 102 m (335 ft; 195 cu) and 105 m (344 ft; 200 cu) with a shallower inclination of between 48° and 52° up to a peak height 58 m (190 ft; 111 cu) for a total volume of 200,158 m3 (7,068,500 cu ft).[111][112] The shallower inclination angle was a step taken to guard against the threat of a collapse and avoid a repeat of the failure at Dahshur.[120] Inside the substructure, builders took further precautions, such as lining chamber pits with limestone.[123] The burial chamber was chiselled out of a single quartzite block measuring 7 m (23 ft) by 2.5 m (8.2 ft) by 1.83 m (6.0 ft) and weighing over 100 t (110 short tons).[123][120]

Before the pyramid lay a mortuary temple, that has been identified as "the Labyrinth" which Classical travellers such as Herodotus and Strabo referred to and which was said to have inspired the 'Labyrinth of Minos'.[124][120] The temple was destroyed in antiquity and can only be partially reconstructed.[124][120] Its floorplan covered an estimated 28,000 m2 (300,000 sq ft).[124] According to Strabo's account, the temple contained as many rooms as there were nomes in Egypt,[125] while Herodotus wrote about being led 'from courtyards into rooms, rooms into galleries, galleries into more rooms, thence into more courtyards'.[120] A limestone statue of Sobek and another of Hathor were discovered here[125] as were two granite shrines each containing two statues of Amenemhat III.[120] A north-south oriented perimeter wall enclosed the entire complex[125] which thus measured 385 m (1,263 ft) by 158 m (518 ft).[120] The causeway has been identified near the south-west corner of the complex, but neither it nor the valley temple have been investigated.[126]

Neferuptah

The pyramid of Neferuptah was built 2 km (1.2 mi) south-east of Amenemhat III's Hawara pyramid. It was excavated by Nagib Farag and Zaky Iskander in 1956.[127] The superstructure of the pyramid is near completely lost and the substructure was found full of groundwater, but her burial was otherwise undisturbed including both her sarcophagus and funerary equipment.[128]

Sculpture

Amenemhat III and Sensuret III are the best attested rulers of the Middle Kingdom by number of statues, with about 80 statues that can be assigned to the former. The sculpture of Amenemhat III continued the tradition of Senusret III, though it pursued a more natural and expressive physiognomy, while retaining an idealized image.[129] A wide range of stones were used for the sculpture of the king, include white limestone, obsidian, chalcedony and copper alloy.[130] Furthermore, the king introduced new and re-interpreted types of sculptures, many of which were inspired by far older works.[17] Two broad facial types can be assigned to Amenemhat III. An expressive style in which the face of the king has its musculature, bone structure, and furrows clearly marked. This style is evidently inspired by the sculpture of Senusret III. A humanized style in which the face is simplified with few or no folds or furrows and averse to sharp transitions between features. These have a generally softer, more youthful expression.[131]

A sculpture of the expressive type in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

A sculpture of the expressive type in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen A sculpture of the humanized type in the Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst, Munich

A sculpture of the humanized type in the Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst, Munich_III._Mottled_diorite%252C_half_life-size._12th_Dynasty._From_Egypt._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%252C_London.jpg.webp) Half-lifesized head in mottled diorite from the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Half-lifesized head in mottled diorite from the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Amenemhat III dressed in panther skin from the Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Amenemhat III dressed in panther skin from the Egyptian Museum, Cairo Granite statue in the Egyptian Collection of the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Granite statue in the Egyptian Collection of the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Egyptian alabaster statuette head of Amenemhat III from the Louvre, Paris

Egyptian alabaster statuette head of Amenemhat III from the Louvre, Paris

Officials

The vizier Kheti (H̱ty) held office around year 29 of Amenemhat III's reign,[132] as is attested on a papyrus from el-Lahun.[133] The papyrus is a business document authored by the vizier in his office discussing payment of two brothers named Ahy-seneb (Ỉhy-snb) for their services.[134] At that time one brother, Ahy-seneb Ankh-ren (ꜥnḫ-rn), was an 'assistant to the treasurer', yet on a later papyrus containing his will, dated to year 44 of Amenemhat III's reign, he had become the 'director of works'.[135][136] This latter papyrus contains two dates: year 44, month II of Shemu, day 13 and year 2, month II of Akhet, day 18.[137] The latter date refers to the reign of either Amenemhat IV or Sobekneferu.[138] There is one other hieratic text and also a limestone table on which Ahy-seneb Ankh-ren is attested.[136] The other brother, Ahy-seneb Wah (Wꜣḥ), was a wab-priest and 'superintendent of priestly orders of Sepdu, lord of the East'.[133][139]

A further vizier datable to the reign was Ameny (Ỉmny).[140] Ameny is attested on two rock inscriptions from Aswan.[141] The first found by Flinders Petrie on the road between Philae and Aswan,[142] and the second found by Jacques de Morgan on the right bank of the river nile between Bar and Aswan.[143] The inscriptions bear the names of his family members,[141] including his wife Sehotepibre Nehy (Sḥtp-ỉb-rꜥ Nḥy) who is also attested on a stela in Copenhagen National Museum.[144]

Khnumhotep (H̱nmw-ḥtp) was an official that held office for at least three decades from Senusret II's first regnal year through to Amenemhat III's reign.[145] At the beginning of Senusret II's reign he was a chamberlain, but by the end of his life he held both the office of vizier and chief steward.[146] His tomb in Dahshur also attests to many other titles including 'high official', 'royal seal-bearer', 'chief lector-priest', 'master of secrets', and 'overseer of the city'.[147][148]

The treasurer Ikhernofret (Y-ẖr-nfrt) was still in office in the early years of the king's reign,[149] as is demonstrated by a funerary stela in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[150] This official is among the best attested for the Middle Kingdom, though there is little known of his family.[149] His funerary stela is dated to Amenemhat III's first regnal year and bears his name along with three of his titles: 'sealbearer of the King of Lower Egypt', 'sole friend of the king', and 'treasurer'.[151][152] The treasurer is mentioned on the funerary stela of an Ameny (Ỉmny) 'chief of staff of the bureau of the vizier'. The latter part of the stela tells of the attendance of Ikhernofret and Sasetet (Sꜣ-sṯt) at a feast in Abydos at the instruction of Senusret III after a campaign against Nubia in his regnal year 19.[153][154] Ameny is also mentioned on the 'stela of Sasetet' dating to the first year of Amenemhat III, where he still held the same position.[155][156] Sasetet holds the title 'chief of staff of the bureau of the treasurer' in that stela.[155]

Another treasurer under Amenemhat III is Senusretankh (S-n-wsrt-ꜥnḫ), who is known from his recently uncovered mastaba at Dahshur, near the pyramid of Senusret III. The surviving fragments of a red granite offering table recovered from the tomb bear the birth and throne names of Amenemhat III. The table further bears numerous other epithets and titles with which the owner connects himself to the king.[157]

Another chief steward, Senbef (Snb=f) is known from an expedition stela found at Mersa and from a papyrus document.[158] The stela contains an image of Amenemhat III presenting offerings to the god Min.[159] Behind the king stands another official, Nebsu (Nbsw) the 'Overseer of the Cabinet of the Head of the South', effectively meaning that he was the head of a workforce. Beneath the image are inscriptions recording two expeditions to Punt alongside the names of the expedition leaders. The leads of the two expeditions are Nebsu himself and his brother Amenhotep (Ỉmn-htp), holding the title of 'scribe in charge of the seal of the treasury'.[160][161]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Proposed dates for the reign of Amenemhat III: c. 1859–1813 BC,[2] c. 1844–1797 BC,[3] c. 1843–1797 BC,[4] c. 1842–1797 BC,[5][6] c. 1842–1794 BC,[7] c. 1831–1786 BC,[8][9] c. 1818–1773 BC.[10]

- ↑ Syncellus attributes his list to Apollodorus, whom himself attributed to Eratosthenes, and himself attributed to 'the scribes of Diospolis', but which is ultimately supposed to originate from none of these, and was instead derived from an Egyptian king list.[34]

- ↑ These include:

The presence of double dates that appear to conflate the reigns of two kings.[51][52]

The co-naming of two kings present on many artefacts, but without dates. This is weak evidence as it is not unusual for two kings, one living and one deceased, to be named together.[53]

Single-dated monuments during the assumed period of co-rule favour the junior partner and this is suggested to indicate the quasi-retirement of the elder king.[54]

Textual evidence for co-regency, but it is scant, indirect, and of malleable interpretation.[55] - ↑ Such as the Egyptologists Robert Delia, Claude Obsomer, and Pierre Tallet.[56][57]

References

- 1 2 3 Schneider 2006, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Oppenheim et al. 2015, p. xix.

- ↑ Lehner 2008, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Leprohon 2001, p. 69.

- ↑ Clayton 1994, p. 84.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 391.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 289.

- ↑ Shaw 2003, p. 483.

- 1 2 3 4 Callender 2003, p. 156.

- 1 2 Krauss & Warburton 2006, p. 492.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Leprohon 2013, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 von Beckerath 1984, p. 199.

- 1 2 3 4 Grajetzki 2006, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 Clayton 1994, pp. 87–88.

- 1 2 Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 4 Clayton 1994, p. 87.

- 1 2 Connor 2015, p. 58.

- ↑ Shute 2001, p. 348.

- ↑ Clagett 1989, p. 113.

- ↑ Redford 1986, p. 34.

- 1 2 Krauss & Warburton 2006, p. 493.

- ↑ Kitchen 1975, pp. 177–179.

- ↑ Kitchen 1979, pp. 539–541.

- ↑ Kitchen 1980, pp. 479–481.

- ↑ Kitchen 2001, p. 237.

- ↑ Ryholt 1997, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Kitchen 1979, pp. 827 & 834.

- ↑ Waddell 1964, p. vii.

- ↑ Redford 2001, p. 336.

- ↑ Hornung, Krauss & Warburton 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Hornung, Krauss & Warburton 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Waddell 1964, pp. 69 & 71.

- ↑ Waddell 1964, p. 224.

- ↑ Waddell 1964, pp. 213.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 94–95.

- 1 2 3 4 Grajetzki 2006, p. 58.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 93 & 96–98.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 93, 95–96 & 99.

- ↑ Roth 2001, p. 440.

- 1 2 Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 95 & 98.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 93 & 95.

- ↑ Callender 2003, p. 158.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 92 & 95–98.

- 1 2 Schneider 2006, p. 70.

- ↑ Grajetzki 2015, p. 306.

- ↑ Schneider 2006, p. 174.

- ↑ Kitchen 1975, pp. 177 & 179.

- ↑ Kitchen 1979, pp. 539 & 541.

- ↑ Kitchen 1980, pp. 479 & 481.

- ↑ Schneider 2006, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Saladino Haney 2020, p. 39.

- ↑ Schneider 2006, pp. 171–173.

- ↑ Saladino Haney 2020, p. 41.

- ↑ Saladino Haney 2020, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Saladino Haney 2020, p. 43.

- ↑ Saladino Haney 2020, p. 40, footnote 7.

- ↑ Schneider 2006, p. 170.

- ↑ Saladino Haney 2020, pp. 39–97.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schneider 2006, p. 173.

- 1 2 Simpson 2001, p. 455.

- ↑ Griffith 1897, p. 40; Griffith 1898, p. Pl. XIV.

- ↑ Grajetzki 2006, p. 180.

- 1 2 Grajetzki 2006, p. 60.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Grimal 1992, p. 170.

- ↑ Ryholt 1997, p. 212.

- ↑ Murnane 1977, pp. 12–13 & footnote. 55.

- 1 2 Grimal 1992, p. 168.

- 1 2 Callender 2003, p. 154.

- 1 2 Callender 2003, p. 155.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 167.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 166.

- ↑ Hintze & Reineke 1989, pp. 145–147.

- 1 2 3 4 Callender 2003, pp. 156–157.

- 1 2 Callender 2003, p. 157.

- ↑ Leprohon 1999, p. 54.

- ↑ Gardiner, Peet & Černý 1955, pp. 66–71.

- ↑ Tallet 2002, pp. 371–372.

- ↑ Tallet 2002, p. 372.

- ↑ Gardiner, Peet & Černý 1955, p. 76.

- ↑ Mumford 1999, p. 882.

- ↑ Gardiner, Peet & Černý 1955, pp. 78–81, 90–121, 133–134, 141–143.

- 1 2 Uphill 2010, p. 46.

- ↑ Castel & Soukiassian 1985, pp. 285 & 288.

- ↑ Mahfouz 2008, p. 275, footnote 130.

- 1 2 Seyfried 1981, pp. 254–256.

- ↑ Couyat & Montet 1912, pp. 40–41 & 51.

- ↑ Shaw & Jameson 1993, p. 97.

- ↑ Seyfried 1981, pp. 105–116.

- ↑ Sadek 1980, pp. 41–43.

- ↑ Rothe, Miller & Rapp 2008, pp. 382–385 & 499.

- ↑ Shaw et al. 2010, pp. 293–294.

- ↑ Darnell & Manassa 2013, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Darnell & Manassa 2013, p. 58.

- ↑ Mahfouz 2008, pp. 253, 259–261.

- ↑ Bard, Fattovich & Manzo 2013, p. 539.

- ↑ Bard, Fattovich & Manzo 2013, p. 537.

- ↑ Mahfouz 2008, pp. 253–255 & 273–274.

- ↑ Zecchi 2010, p. 38.

- ↑ Callender 2003, pp. 152–153 & 157.

- ↑ Callender 2003, p. 152.

- ↑ Chanson 2004, p. 544.

- ↑ Gorzo 1999, p. 429.

- ↑ Chanson 2004, pp. 545.

- ↑ Clayton 1994, p. 88.

- ↑ Callender 2003, pp. 157–158.

- 1 2 Verner 2001, p. 421.

- ↑ Lehner 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Allen 2008, p. 31.

- 1 2 Lehner 2008, p. 179.

- 1 2 Verner 2001, p. 422.

- 1 2 Verner 2001, p. 465.

- 1 2 Lehner 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Verner 2001, pp. 422–423.

- 1 2 3 Verner 2001, p. 423.

- 1 2 Lehner 2008, p. 180.

- ↑ Verner 2001, pp. 424–426.

- ↑ Lehner 2008, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Verner 2001, p. 424.

- 1 2 Verner 2001, p. 427.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Lehner 2008, p. 181.

- ↑ Verner 2001, pp. 427–428.

- ↑ Grajetzki 2006, pp. 58–59.

- 1 2 3 Verner 2001, p. 428.

- 1 2 3 Verner 2001, p. 430.

- 1 2 3 Verner 2001, p. 431.

- ↑ Verner 2001, pp. 431–432.

- ↑ Farag & Iskander 1971.

- ↑ Hölzl 1999, p. 437.

- ↑ Connor 2015, pp. 58 & 60.

- ↑ Connor 2015, p. 59.

- ↑ Connor 2015, pp. 60–62.

- ↑ Grajetzki 2009, p. 34.

- 1 2 Griffith 1897, p. 35.

- ↑ Griffith 1897, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Griffith 1897, pp. 31 & 35.

- 1 2 JGU 2022, Person PD 189.

- ↑ Griffith 1897, pp. 31–35; Griffith 1898, p. Plate XII.

- ↑ Griffith 1897, p. 34.

- ↑ JGU 2022, Person wꜥb; ḥrj-sꜣ n spdw nb jꜣbtt jḥjj-snb/wꜣḥ.

- ↑ de Meulenaere 1981, p. 78–79.

- 1 2 JGU 2022, Person PD 116.

- ↑ Petrie 1888, p. Pl. VI, no. 137.

- ↑ de Morgan et al. 1894, pp. 29–31, no. 10.

- ↑ Thirion 1995, p. 174.

- ↑ Allen 2008, pp. 29–31.

- ↑ Allen 2008, p. 29.

- ↑ Allen 2008, pp. 32.

- ↑ JGU 2022, Person DAE 161.

- 1 2 Tolba 2016, p. 135.

- ↑ Universität zu Köln 2021.

- ↑ Tolba 2016, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ JGU 2022, Person PD 27.

- ↑ MAH 2021.

- ↑ JGU 2022, Person PD 551.

- 1 2 Louvre 2021.

- ↑ JGU 2022, Person PD 94.

- ↑ Yamamoto 2021, pp. 249–255.

- ↑ JGU 2022, Person DAE 204.

- ↑ Bard & Fattovich 2018, p. 64.

- ↑ Bard & Fattovich 2018, p. 65.

- ↑ JGU 2022, sš ḥr.j-ḫtm n pr-ḥḏ.

Bibliography

- "136780: Stele". Arachne. Universität zu Köln. 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- Allen, James (2008). "The Historical Inscription of Khnumhotep at Dahshur: Preliminary Report". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 352 (352): 29–39. doi:10.1086/BASOR25609300. ISSN 2161-8062. JSTOR 25609300. S2CID 163394832.

- Bard, Kathryn; Fattovich, Rodolfo; Manzo, Andrea (2013). "The ancient harbor at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis and how to get there: New evidence of Pharaonic seafaring expeditions in the Red Sea". In Förster, Frank; Riemer, Heiko (eds.). Desert Road Archaeology in Ancient Egypt and Beyond. Cologne: Heinrich-Barth-Institut. pp. 533–557. ISBN 9783927688414.

- Bard, Kathryn; Fattovich, Rodolfo (2018). Seafaring Expeditions to Punt in the Middle Kingdom. Culture and history of the ancient Near East, 96. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004368507.

- Callender, Gae (2003). "The Middle Kingdom Renaissance (c. 2055–1650 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 137–171. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Castel, Georges; Soukiassian, Georges (1985). "Dépôt de stèles dans le sanctuaire du Nouvel Empire au Gebel Zeit [avec 5 planches]". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale (in French) (85): 285–293. ISSN 2429-2869.

- Chanson, Hubert (2004). Hydraulics of Open Channel Flow. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 9780750659789.

- Clagett, Marshall (1989). Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871691842.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- Connor, Simon (2015). "The statue of the steward Nemtyhotep (Berlin ÄM 15700) and some considerations about Royal and Private Portrait under Amenemhat III". In Miniaci, Gianluca; Grajetzki, Wolfram (eds.). The World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000–1550 BC) Contributrions on Archaeology, Art, Religion, and Written Sources. Vol. 1. London: Golden House Publications. pp. 57–79. ISBN 978-1-906137-43-4.

- Couyat, Jules; Montet, Pierre (1912). Les inscriptions hiéroglyphiques et hiératiques du Ouâdi Hammâmât. Mémoires publiés par l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire (in French) (34 ed.). Le Caire: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. OCLC 422048959.

- Darnell, John C.; Manassa, Colleen (2013). "A Trustworthy Seal-Bearer on a Mission: The Monuments of Sabastet from the Khepren Diorite Quarries". In Parkinson, Richards; Fischer-Elfert, Hans-Werner (eds.). Studies on the Middle Kingdom. Philippika (41 ed.). Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag. pp. 55–92. ISBN 9783447063968.

- de Morgan, Jacques; Bouriant, Urbain; Legrain, Georges; Jéquier, Gustave; Barsanti, Alfred (1894). Catalogue des Monuments et Inscriptions de l'Egypt Antique. Haute Égypt (in French). Vol. 1. Vienna: Adolphe Holzhausen. OCLC 730929779.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. OCLC 602048312.

- Farag, Naguib; Iskander, Z (1971). The discovery of Neferwptah. Cairo: General Organization for Govt. Print. Offices. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

- Gardiner, Alan; Peet, Eric; Černý, Jaroslavl (1955). The Inscriptions of Sinai : Translations and Commentary. Vol. 2. London: Egypt Exploration Society. OCLC 941051594.

- Gorzo, Darlene (1999). "Gurob". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 429–433. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2006). The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: History, Archaeology and Society. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-3435-6.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2009). Court Officials of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780715637456.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2015). Oppenheim, Adela; Arnold, Dorothea; Arnold, Dieter; Yamamoto, Kumiko (eds.). Ancient Egypt Transformed: the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588395641.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1897). The Petrie Papyri : Hieratic Papyri from Kahun and Gurob (Principally of the Middle Kingdom). Vol. 1. London: Bernard Quaritch. doi:10.11588/diglit.6444.

- Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1898). The Petrie Papyri : Hieratic Papyri from Kahun and Gurob (Principally of the Middle Kingdom). Vol. 2. London: Bernard Quaritch. doi:10.11588/diglit.6445.

- Hintze, Fritz; Reineke, Walter (1989). Felsinschriften aus dem sudanesischen Nubien. Publikation der Nubien-Expedition 1961–1963. Vol. I. Berlin: Akedemie Verlag. ISBN 3-05-000370-7.

- Hölzl, Christian (1999). "Hawara". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 436–438. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David A. (2006). "The Editors: Royal Annals". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Leiden: Brill. pp. 19–25. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5.

- Ilin-Tomich, Alexander (n.d.). "Persons and Names of the Middle Kingdom". Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz. Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1975). Ramesside Inscriptions: Historical and Biographical. Vol. 1. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-903563-08-8.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1979). Ramesside Inscriptions: Historical and Biographical. Vol. 2. Oxford: Blackwell. OCLC 258591788.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1980). Ramesside Inscriptions: Historical and Biographical. Vol. 3. Oxford: Blackwell. OCLC 254744548.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2001). "King Lists". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 234–238. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David (2006). "Conclusions and Chronological Tables". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Leiden: Brill. pp. 473–498. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (1999). "Middle Kingdom". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 50–56. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2001). "Amenemhat III". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Writings from the ancient world. Vol. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

- Mahfouz, El-Sayed (2008). "Amenemhat III au ouadi Gaouasis". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale (in French) (108): 253–279. ISSN 2429-2869.

- de Meulenaere, Herman (1981). "Contributions à la prospographie du Moyen Empire [1. - Le vizir Imeny. 2. - Quelques anthroponymes d'Edfou du Moyen Empire. 3. - Une stèle d' Elkab] [avec 1 plance]". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale (in French). 81 (1): 77–85. ISSN 2429-2869.

- Mumford, Gregory Duncan (1999). "Serabit el-Khadim". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 881–885. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Murnane, William (1977). Ancient Egyptian Coregencies. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. Vol. 40. Chicago, IL: The Oriental Institute. OCLC 462126791.

- Oppenheim, Adela; Arnold, Dorothea; Arnold, Dieter; Yamamoto, Kumiko, eds. (2015). Ancient Egypt Transformed: the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588395641.

- Petrie, Flinders (1888). A Season in Egypt, 1887. London: Field & Tuer, "The Leadenhall Press", EC. OCLC 314103922.

- Redford, Donald B. (1986). Pharaonic King-lists, Annals, and Day-books. Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 4. Mississauga: Benben Rubl. ISBN 0920168078.

- Redford, Donald B. (2001). "Manetho". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 336–337. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Roth, Silke (2001). Die Königsmütter des Alten Ägypten von der Frühzeit bis zum Ende der 12. Dynastie (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3-447-04368-7.

- Rothe, Russel; Miller, William; Rapp, George (2008). Pharaonic Inscriptions from the Southern Eastern Desert of Egypt. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-147-4.

- Ryholt, Kim (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt During the Second Intermediate Period, C. 1800-1550 B.C. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-7289-421-0.

- Sadek, Ashraf (1980). The Amethyst Mining Inscriptions of Wadi el-Hudi Part I : Text. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 0-85668-162-8.

- Saladino Haney, Lisa (2020). Visualizing Coregency. An Exploration of the Link between Royal Image and Co-Rule during the Reign of Senwosret III and Amenemhet III. Brill, London, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-42214-8.

- Schneider, Thomas (2006). "The Relative Chronology of the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos Period (Dyns. 12-17)". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Leiden: Brill. pp. 168–196. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5.

- Seyfried, Karl-Joachim (1981). Beiträge zu den Expeditionen des Mittleren Reiches in die Ost-Wüste. Hildesheim: Hildesheim Gerstenberg Verlag. ISBN 3806780560.

- Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert (1993). "Amethyst Mining in the Eastern Desert: A Preliminary Survey at Wadi el-Hudi". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 79: 81–97. doi:10.2307/3822159. ISSN 0307-5133. JSTOR 3822159.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Shaw, Ian; Bloxam, Elisabeth; Heldal, Tom; Storemyr, Per (2010). "Quarrying and landscape at Gebel el-Asr in the Old and Middle Kingdoms". In Raffaele, Francesco; Nuzzollo, Massimiliano; Incordino, Ilaria (eds.). Recent Discoveries and Latest Researches in Egyptology : Proceedings of the First Neapolitan Congress of Egyptology, Naples, June 18th-20th 2008. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz Verlag. pp. 293–312. ISBN 978-3-447-06251-0.

- Shute, Charles (2001). "Mathematics". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 348–351. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Simpson, William Kelly (2001). "Twelfth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 453–457. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- "Stèle de Sasatis". Louvre (in French). Louvre. 13 January 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- "Stèle funéraire : Sésostris III (an 19, soit 1868 av. JC selon l'inscription)". Musée d'Art et d'Histoire de Genève (in French). Musée d'Art et d'Histoire de Genève. 10 July 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- Tallet, Pierre (2002). "Notes sur le ouadi Maghara et sa région au Moyen Empire". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale (in French) (102): 371–378. ISSN 2429-2869.

- Thirion, Michelle (1995). "Notes d'Onomastique Contribution à une Revision du Ranke PN [Dixième Série". Revue d'Égyptologie (in French) (46): 171–186. ISSN 1783-1733.

- Tolba, Nevine Hussein Abd el moneim (2016). "La stèle CGC 20140 d'Ikhernofret au Grand Musée égyptien GEM:20140" (PDF). The Conference Book of the General Union of Arab Archaeologists (in French) (19): 135–170. doi:10.21608/cguaa.2016.29699. ISSN 2536-9938.

- Uphill, Eric (2010). Pharaoh's Gateway to Eternity : The Hawara Labyrinth of Amenemhat III. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7103-0627-2.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1984). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. München: Deutscher Kunstverlag. ISBN 9783422008328.

- Waddell, William Gillan (1964) [1940]. Page, Thomas Ethelbert; Capps, Edward; Rouse, William Henry Denham; Post, Levi Arnold; Warmington, Eric Herbert (eds.). Manetho with an English Translation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 610359927.

- Yamamoto, Kei (2021). "Treasurer Senwosretankh, favored of Amenemhat III". In Geisen, Christina; Li, Jean; Shubert, Steven; Yamamoto, Kei (eds.). His good name: essays on identity and self-presentation in ancient Egypt in honor of Ronald J. Leprohon. Atlanta, GA: Lockwood Press. pp. 249–255. ISBN 9781948488372.

- Zecchi, Marco (2010). Sobek of Shedet : The Crocodile God in the Fayyum in the Dynastic Period. Studi sull'antico Egitto. Todi: Tau Editrice. ISBN 978-88-6244-115-5.