| Ptolemy III Euergetes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek: Πτολεμαῖος Εὐεργέτης | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

King of the Ptolemaic Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 28 January 246 – November/December 222 BC[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ptolemy II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Ptolemy IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Berenice II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Ptolemy IV Arsinoe III Alexander Magas Berenice | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Ptolemy II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Arsinoe I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | c. 280 BC[1] Kos or Egypt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | November/December 222 BC (aged c. 58)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Alexandria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ptolemaic dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ptolemy III Euergetes (Greek: Πτολεμαῖος Εὐεργέτης, romanized: Ptolemaios Euergetes, "Ptolemy the Benefactor"; c. 280 – November/December 222 BC) was the third pharaoh of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt from 246 to 222 BC. The Ptolemaic Kingdom reached the height of its military and economic power during his kingship, as initiated by his father Ptolemy II Philadelphus.

Ptolemy III was the eldest son of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe I. When Ptolemy III was young, his mother was disgraced and he was removed from the succession. He was restored as heir to the throne in the late 250s BC and succeeded his father as king without issue in 246 BC. On his succession, Ptolemy III married Berenice II, reigning queen of Cyrenaica, thereby bringing her territory into the Ptolemaic realm. In the Third Syrian War (246–241 BC), Ptolemy III invaded the Seleucid empire and won a near total victory, but was forced to abandon the campaign as a result of an uprising in Egypt. In the aftermath of this rebellion, Ptolemy forged a closer bond with the Egyptian priestly elite, which was codified in the Canopus decree of 238 BC and set a trend for Ptolemaic power in Egypt for the rest of the dynasty. In the Aegean, Ptolemy III suffered a major setback when his fleet was defeated by the Antigonids at the Battle of Andros around 246 BC, but he continued to offer financial support to their opponents in mainland Greece for the rest of his reign. At his death, Ptolemy III was succeeded by his eldest son, Ptolemy IV.

Background and early life

Ptolemy III was born some time around 280 BC, as the eldest son of Ptolemy II and his first wife Arsinoe I, daughter of King Lysimachus of Thrace. His father had become co-regent of Egypt in 284 BC and sole ruler in 282 BC. Around 279 BC, the collapse of Lysimachus' kingdom led to the return to Egypt of Ptolemy II's sister Arsinoe II, who had been married to Lysimachus. A conflict quickly broke out between Arsinoe I and Arsinoe II. Sometime after 275 BC, Arsinoe I was charged with conspiracy and exiled to Coptos.[3] When Ptolemy II married Arsinoe II probably in 273/2 BC, her victory in this conflict was complete. As children of Arsinoe I, Ptolemy III and his two siblings seem to have been removed from the succession after their mother's fall.[4] This political background may explain why Ptolemy III seems to have been raised on Thera in the Aegean, rather than in Egypt.[5][1] His tutors included the poet and polymath Apollonius of Rhodes, later head of the Library of Alexandria.[6]

From 267 BC, a figure known as Ptolemy "the Son" was co-regent with Ptolemy II. He led naval forces in the Chremonidean war (267–261 BC), but revolted in 259 BC at the beginning of the Second Syrian War and was removed from the co-regency. Some scholars have identified Ptolemy the Son with Ptolemy III. This seems unlikely, since Ptolemy III was probably too young to lead forces in the 260s and does not seem to have suffered any of the negative consequences that would be expected if he had revolted from his father in 259 BC. Chris Bennett has argued that Ptolemy the Son was a son of Arsinoe II by Lysimachus.[7][notes 1] Around the time of the rebellion, Ptolemy II legitimised the children of Arsinoe I by having them posthumously adopted by Arsinoe II.[4]

In the late 250s BC, Ptolemy II arranged the engagement of Ptolemy III to Berenice, the sole child of Ptolemy II's half-brother King Magas of Cyrene.[8] The decision to single Ptolemy III out for this marriage indicates that, by this time, he was the heir presumptive. On his father's death, Ptolemy III succeeded him without issue, taking the throne on 28 January 246 BC.[1]

Reign

Cyrenaica (246 BC)

Cyrene had been the first Ptolemaic territory outside Egypt, but Magas had rebelled against Ptolemy II and declared himself king of Cyrenaica in 276 BC. The aforementioned engagement of Ptolemy III to Berenice had been intended to lead to the reunification of Egypt and Cyrene after Magas' death. However, when Magas died in 250 BC, Berenice's mother Apame refused to honour the agreement and invited an Antigonid prince, Demetrius the Fair to Cyrene to marry Berenice instead. With Apame's help, Demetrius seized control of the city, but he was assassinated by Berenice.[9] A republican government, led by two Cyrenaeans named Ecdelus and Demophanes, controlled Cyrene for four years.[10]

It was only with Ptolemy III's accession in 246 BC, that the wedding of Ptolemy III and Berenice seems to have actually taken place. Ptolemaic authority over Cyrene was forcefully reasserted. Two new port cities were established, named Ptolemais and Berenice (modern Tolmeita and Benghazi) after the dynastic couple. The cities of Cyrenaica were unified in a League overseen by the king, as a way of balancing the cities' desire for political autonomy against the Ptolemaic desire for control.[11]

Third Syrian War (246–241 BC)

%252C_Antioch_mint.jpg.webp)

In July 246 BC, Antiochus II, king of the Seleucid empire, died suddenly. By his first wife Laodice I, Antiochus II had had a son, Seleucus II, who was about 19 years old in 246 BC. However, in 253 BC, he had agreed to repudiate Laodice and marry Ptolemy III's sister Berenice. Antiochus II and Berenice had a son named Antiochus, who was still an infant when his father died. A succession dispute broke out immediately after Antiochus II's death. Ptolemy III quickly invaded Syria in support of his sister and her son, marking the beginning of the Third Syrian War (also known as the Laodicean War).[12][13]

An account of the initial phase of this war, written by Ptolemy III himself, is preserved on the Gurob papyrus. At the outbreak of war, Laodice I and Seleucus II were based in western Asia Minor, while the widowed Queen Berenice was in Antioch. The latter quickly seized control of Cilicia to prevent Laodice I from entering Syria. Meanwhile, Ptolemy III marched along the Levantine coast encountering minimal resistance. The cities of Seleucia and Antioch surrendered to him without a fight in late autumn.[14] At Antioch, Ptolemy III went to the royal palace to plan his next moves with Berenice in person, only to discover that she and her young son had been murdered.[15][13]

Rather than accept defeat in the face of this setback, Ptolemy III continued his campaign through Syria and into Mesopotamia, where he conquered Babylon at the end of 246 or beginning of 245 BC.[16] In light of this success, he may have been crowned 'Great King' of Asia.[17] Early in 245 BC, he established a governor of the land 'on the other side' of the Euphrates, indicating an intention to permanently incorporate the region into the Ptolemaic kingdom.[18][19]

At this point however, Ptolemy III received notice that a revolt had broken out in Egypt and he was forced to return home to suppress it.[20] By July 245 BC, the Seleucids had recaptured Mesopotamia.[21] The Egyptian revolt is significant as the first of a series of native Egyptian uprisings which would trouble Egypt for the next century. One reason for this revolt was the heavy tax-burdens placed on the people of Egypt by Ptolemy III's war in Syria. Furthermore, papyri records indicate that the inundation of the Nile river failed in 245 BC, resulting in famine.[19] Climate proxy studies suggest that this resulted from changes of the monsoon pattern at the time, resulting from a volcanic eruption which took place in 247 BC.[22]

After his return to Egypt and suppression of the revolt, Ptolemy III made an effort to present himself as a victorious king in both Egyptian and Greek cultural contexts. Official propaganda, like OGIS 54, an inscription set up in Adulis, vastly exaggerated Ptolemy III's conquests, claiming even Bactria among his conquests.[23] At the new year in 243 BC, Ptolemy III incorporated himself and his wife Berenice II into the Ptolemaic state cult, to be worshipped as the Theoi Euergetai (Benefactor Gods), in honour of his restoration to Egypt of statues found in the Seleucid territories, which had been seized by the Persians.[18][19]

There may also have been a second theatre to this war in the Aegean. The general Ptolemy Andromachou, ostensibly an illegitimate son of Ptolemy II and the half-brother of Ptolemy III,[24] captured Ephesus from the Seleucids in 246 BC. At an uncertain date around 245 BC, he fought a sea-battle at Andros against King Antigonus II of Macedon, in which the Ptolemaic forces were defeated. It appears that he then led an invasion of Thrace, where Maroneia and Aenus were under Ptolemaic control as of 243 BC. Ptolemy Andromachou was subsequently assassinated at Ephesus by Thracian soldiers under his control.[25][26]

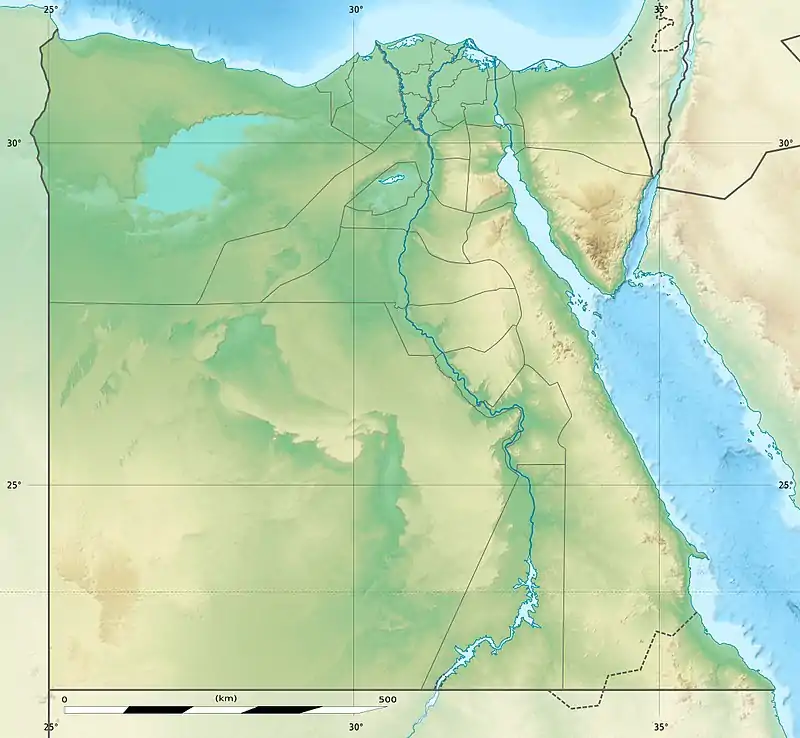

The only further action known from the war is some fighting near Damascus in 242 BC.[27] Shortly after this, in 241 BC, Ptolemy made peace with the Seleucids, retaining all the conquered territory in Asia Minor and northern Syria. Nearly the whole Mediterranean coast from Maroneia in Thrace to the Syrtis in Libya was now under Ptolemaic control. One of the most significant acquisitions was Seleucia Pieria, the port of Antioch, whose loss was a significant economic and logistical set-back for the Seleucids.[28]

Later reign (241–222 BC)

The conclusion of the Third Syrian War marked the end of military intervention in the Seleucid territories, but Ptolemy III continued to offer covert financial assistance to the opponents of Seleucus II. From 241 BC, this included Antiochus Hierax, the younger brother of Seleucus II, who rebelled against his brother and established his own separate kingdom in Asia Minor. Ptolemy III sent military forces to support him only when a group of Galatian mercenaries rebelled against him[29] but is likely to have supported him more tacitly throughout his conflict with Seleucus II. He offered similar support to Attalus I, the dynast of Pergamum, who took advantage of this civil conflict to expand his territories in northwestern Asia Minor. When the Seleucid general Achaeus was sent in 223 BC to reconquer the territories in Asia Minor that had been lost to Attalus, Ptolemy III sent his son Magas with a military force to aid Attalus, but he was unable to prevent Attalus' defeat.[30]

Ptolemy III maintained his father's hostile policy to Macedonia. This probably involved direct conflict with Antigonus II during the Third Syrian War, but after the defeat at Andros in c. 245 BC, Ptolemy III seems to have returned to the policy of indirect opposition, financing enemies of the Antigonids in mainland Greece. The most prominent of these was the Achaian League, a federation of Greek city-states in the Peloponnese that were united by their opposition to Macedon. From 243 BC, Ptolemy III was the nominal leader (hegemon) and military commander of the League[31] and supplied them with a yearly payment.[32] After 240 BC, Ptolemy also forged an alliance with the Aetolian League in northwest Greece.[33] From 238 to 234 BC, the two leagues waged the Demetrian War against Macedon with Ptolemaic financial support.[34]

However, in 229 BC, the Cleomenean War (229–222 BC) broke out between the Achaian League and Cleomenes III of Sparta. As a result, in 226 BC, Aratos of Sicyon the leader of the Achaian League forged an alliance with the Macedonian king Antigonus III. Ptolemy III responded by immediately breaking off relations with the Achaian League and redirecting his financial support to Sparta. Most of the rest of the Greek states were brought under the Macedonian umbrella in 224 BC when Antigonus established the "Hellenic League". However Aetolia and Athens remained hostile to Macedon and redoubled their allegiance to Ptolemy III. In Athens, in 224 BC, extensive honours were granted to Ptolemy III to entrench their alliance with him, including the creation of a new tribe named Ptolemais in his honour and a new deme named Berenicidae in honour of Queen Berenice II.[35] The Athenians instituted a state religious cult in which Ptolemy III and Berenice II were worshipped as gods, including a festival, the Ptolemaia. The centre of the cult was the Ptolemaion,[36] which also served as the gymnasium where young male citizens undertook civic and military training.[37]

Cleomenes III suffered serious defeats in 223 BC and Ptolemy III abandoned his support for him in the next year – probably as a result of an agreement with Antigonus. The Egyptian king seems to have been unwilling to commit actual troops to Greece, particularly as the threat of renewed war with the Seleucids was looming. Cleomenes III was defeated and forced to flee to Alexandria, where Ptolemy III offered him hospitality and promised to help restore him to power.[38] However, these promises were not fulfilled, and the Cleomenian War would in fact be the last time that the Ptolemies intervened in mainland Greece.[36]

In November or December 222 BC, shortly after Cleomenes' arrival in Egypt and Magas' failure in Asia Minor, Ptolemy III died of natural causes.[39][1] He was succeeded by his son Ptolemy IV without incident.

Regime

Pharaonic ideology and Egyptian religion

Ptolemy III built on the efforts of his predecessors to conform to the traditional model of the Egyptian pharaoh. He was responsible for the first known example of a series of decrees published as trilingual inscriptions on massive stone blocks in Ancient Greek, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and demotic. Earlier decrees, like the Satrap stele and the Mendes stele, had been in hieroglyphs alone and had been directed at single individual sanctuaries. By contrast, Ptolemy III's Canopus decree was the product of a special synod of all the priests of Egypt, which was held in 238 BC. The decree instituted a number of reforms and represents the establishment of a full partnership between Ptolemy III as pharaoh and the Egyptian priestly elite. This partnership would endure until the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty. In the decree, the priesthood praise Ptolemy III as a perfect pharaoh. They emphasise his support of the priesthood, his military success in defending Egypt and in restoring religious artefacts supposedly held by the Seleucids, and his good governance, especially an incident when Ptolemy III imported, at his own expense, a vast amount of grain to compensate for a weak inundation. The rest of the decree consists of reforms to the priestly orders (phylai). The decree also added a leap day to the Egyptian calendar of 365 days, and instituted related changes in festivals. Ptolemy III's infant daughter Berenice died during the synod and the stele arranges for her deification and ongoing worship. Further decrees would be issued by priestly synods under Ptolemy III's successors. The best-known examples are the Decree of Memphis passed by his son Ptolemy IV in about 218 BC and the Rosetta Stone erected by his grandson Ptolemy V in 196 BC.

The Ptolemaic kings before Ptolemy III, his grandfather Ptolemy I and his father Ptolemy II, had followed the lead of Alexander the Great in prioritising the worship of Amun, worshipped at Karnak in Thebes among the Egyptian deities. With Ptolemy III the focus shifted strongly to Ptah, worshipped at Memphis. Ptah's earthly avatar, the Apis bull came to play a crucial role in royal new year festivals and coronation festivals. This new focus is referenced by two elements of Ptolemy III's Pharaonic titulary: his nomen which included the phrase Mery-Ptah (beloved of Ptah), and his golden Horus name, Neb khab-used mi ptah-tatenen (Lord of the Jubilee-festivals as well as Ptah Tatjenen).[40]

Ptolemy III financed construction projects at temples across Egypt. The most significant of these was the Temple of Horus at Edfu, one of the masterpieces of ancient Egyptian temple architecture and now the best-preserved of all Egyptian temples. The king initiated construction on it on 23 August 237 BC.[41] Work continued for most of the Ptolemaic dynasty; the main temple was finished in the reign of Ptolemy IV in 231 BC, and the full complex was only completed in 142 BC, during the reign of Ptolemy VIII, while the reliefs on the great pylon were finished in the reign of Ptolemy XII. Other construction work took place at a range of sites, including (from north to south):

- Serapeum of Alexandria

- Temple of Osiris at Canopus;[41]

- Decorative work on the Temple of Isis at Behbeit El Hagar, near Sebennytos;[41]

- A sacred lake in the Temple of Montu at Medamud;[41]

- The Gateway of Ptolemy III in the Temple of Khonsu and decorative work on the Temple of Opet at Karnak Thebes.[41][42]

- Temple of Khnum at Esna

- A birth house at the Temple of Isis at Philae.[41]

Scholarship and culture

Ptolemy III continued his predecessor's sponsorship of scholarship and literature. The Great Library in the Musaeum was supplemented by a second library built in the Serapeum. He was said to have had every book unloaded in the Alexandria docks seized and copied, returning the copies to their owners and keeping the originals for the Library.[43] Galen attests that he borrowed the official manuscripts of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides from Athens and forfeited the considerable deposit he paid for them in order to keep them for the Library rather than returning them.[44] The most distinguished scholar at Ptolemy III's court was the polymath and geographer Eratosthenes, most noted for his remarkably accurate calculation of the circumference of the world. Other prominent scholars include the mathematicians Conon of Samos and Apollonius of Perge.[45]

Red Sea trade

Ptolemy III's reign was also marked by trade with other contemporaneous polities. In the 1930s, excavations by Mattingly at a fortress close to Port Dunford (the likely Nikon of antiquity) in present-day southern Somalia yielded a number of Ptolemaic coins. Among these pieces were 17 copper coins from the reigns of Ptolemy III to Ptolemy V, as well as late Imperial Rome and Mamluk Sultanate coins.[46]

Marriage and issue

Ptolemy III married his half-cousin Berenice of Cyrene in 244/243 BC. Their children were:

| Name | Image | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsinoe III |  | 246/5 BC | 204 BC | Married her brother Ptolemy IV in 220 BC. |

| Ptolemy IV |  | May/June 244 BC | July/August 204 BC | King of Egypt from 222 to 204 BC. |

| A son | July/August 243 BC | Perhaps 221 BC | Name unknown, possibly 'Lysimachus'. He was probably killed in or before the political purge of 221 BC.[47] | |

| Alexander | September/October 242 BC | Perhaps 221 BC | He was probably killed in or before the political purge of 221 BC.[48] | |

| Magas | November/December 241 BC | 221 BC | Scalded to death in his bath by Theogos or Theodotus, at the orders of Ptolemy IV.[49] | |

| Berenice | January/February 239 BC | February/March 238 BC | Posthumously deified on 7 March 238 BC by the Canopus Decree, as Berenice Anasse Parthenon (Berenice, mistress of virgins).[50] |

See also

- History of Ptolemaic Egypt

- Ptolemais – towns and cities named after members of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Notes

- ↑ This identification of Ptolemy son of Lysimachus, with Ptolemy the Son who is attested as Ptolemy II's co-regent is argued in detail by Chris Bennett. Other scholars have identified the co-regent as an illegitimate or otherwise unknown son of Ptolemy II.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy III". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- 1 2 Ronald J. Leprohon, The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary, Society of Biblical Literature (2013), p. 190.

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 36

- 1 2 Bennett, Chris. "Arsinoe II". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ↑ IG XII.3 464

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 63

- ↑ Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy "the son"". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ↑ Justin 26.3.2

- ↑ Justin 26.3.3–6; Catullus 66.25–28

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 44–46

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Bevan

- 1 2 Hölbl 2001, p. 48

- ↑ Gurob Papyrus

- ↑ Justin Epitome of Pompeius Trogus 27.1, Polyaenus Stratagems 8.50

- ↑ Ptolemy III chronicle; Appian, Syriaca 11.65.

- ↑ OGIS 54 (the 'Adulis inscription').

- 1 2 Jerome, Commentary on Daniel 11.7–9

- 1 2 3 Hölbl 2001, p. 49

- ↑ Justin 27.1.9; Porphyry FGrH 260 F43

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 49–50

- ↑ "Volcanic eruptions linked to social unrest in Ancient Egypt". EurekAlert. 2017.

- ↑ Rossini, A. (December 2021). "Iscrizione trionfale di Tolomeo III ad Aduli". Axon. 5 (2): 93–142. doi:10.30687/Axon/2532-6848/2021/02/005. S2CID 245042574.

- ↑ Ptolemy Andromachou by Chris Bennett

- ↑ P. Haun 6; Athenaeus Deipnosophistae 13.593a

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 50

- ↑ Porphyry FGrH 260 F 32.8

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 50–51

- ↑ Porphyry FGrH 260 F32.8

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 53–4

- ↑ Plutarch Life of Aratus 24.4

- ↑ Plutarch Life of Aratus 41.5

- ↑ Frontinus Stratagems 2.6.5; P. Haun. 6

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 51

- ↑ Pausanias 1.5.5; Stephanus of Byzantium sv. Βερενικίδαι

- 1 2 Hölbl 2001, p. 52

- ↑ Pélékidis, Ch. (1962). Histoire de l'éphébie attique des origines à 31 av. J.-C. pp. 263–64.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Cleomenes 29–32

- ↑ Polybius 2.71.3; Justin 29.1 claims that Ptolemy III was murdered by his son, but this is probably slander.

- ↑ Holbl 2001, pp. 80–81

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Holbl 2001, pp. 86–87

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 163. ISBN 9780500283967.

- ↑ Galen Commentary on the Epidemics 3.17.1.606

- ↑ El-Abbadi, Mostafa. "Library of Alexandria". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 63–65

- ↑ Hildegard Temporini, ed. (1978). Politische Geschichte: (Provinzien und Randvölker: Mesopotamien, Armenien, Iran, Südarabien, Rom und der Ferne Osten), Part 2, Volume 9. Walter de Gruyter. p. 977. ISBN 3110071754. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Lysimachus by Chris Bennett

- ↑ Alexander by Chris Bennett

- ↑ Magas by Chris Bennett

- ↑ Berenice by Chris Bennett

Bibliography

External links

- Ptolemy Euergetes I at LacusCurtius — (Chapter VI of E. R Bevan's House of Ptolemy, 1923)

- Ptolemy III — (Royal Egyptian Genealogy)

- Ptolemy III Euergetes entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Bust of Ptolemy III from Herculaneum – now in the Museo Nazionale, Naples.