| Neferirkare Kakai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neferirkara, Neferarkare, Nefercherês | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | Eight, ten, eleven or much less likely twenty years, in the early to mid-25th century BCE.[note 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Sahure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Neferefre (most likely) or Shepseskare | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Khentkaus II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Neferefre ♂, Nyuserre Ini ♂, Iryenre ♂, Khentkaus III ♀ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Sahure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Meretnebty (also known as Neferetnebty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Neferirkare | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid Ba-Neferirkare Sun temple Setibre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 5th Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Neferirkare Kakai (known in Greek as Nefercherês, Νεφερχέρης) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the third king of the Fifth Dynasty. Neferirkare, the eldest son of Sahure with his consort Meretnebty, was known as Ranefer A before he came to the throne. He acceded the day after his father's death and reigned for eight to eleven years, sometime in the early to mid-25th century BCE. He was himself very likely succeeded by his eldest son, born of his queen Khentkaus II, the prince Ranefer B who would take the throne as king Neferefre. Neferirkare fathered another pharaoh, Nyuserre Ini, who took the throne after Neferefre's short reign and the brief rule of the poorly known Shepseskare.

Neferirkare was acknowledged by his contemporaries as a kind and benevolent ruler, intervening in favour of his courtiers after a mishap. His rule witnessed a growth in the number of administration and priesthood officials, who used their expanded wealth to build architecturally more sophisticated mastabas, where they recorded their biographies for the first time. Neferirkare was the last pharaoh to significantly modify the standard royal titulary, separating the nomen or birth name, from the prenomen or throne name. From his reign onwards, the former was written in a cartouche preceded by the "Son of Ra" epithet. His rule witnessed continuing trade relations with Nubia to the south and possibly with Byblos on the Levantine coast to the north.

Neferirkare started a pyramid for himself in the royal necropolis of Abusir, called Ba-Neferirkare meaning "Neferirkare is a Ba". It was initially planned to be a step pyramid, a form which had not been employed since the days of the Third Dynasty circa 120 years earlier. This plan was modified to transform the monument into a true pyramid, the largest in Abusir, which was never completed owing to the death of the king. In addition, Neferirkare built a temple to the sun god Ra called Setibre, that is "Site of the heart of Ra". Ancient sources state that it was the largest one built during the Fifth Dynasty but as of the early 21st century it has not yet been located.

After his death, Neferirkare benefited from a funerary cult taking place in his mortuary temple, which had been completed by his son Nyuserre Ini. This cult seems to have disappeared at the end of the Old Kingdom period, although it might have been revived during the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, albeit in a very limited form. In all probability, it was also around this time that the story of the Papyrus Westcar was first written, a tale where Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare are said to be brothers, the sons of Ra with a woman Rededjet.

Sources

Contemporaneous sources

Neferirkare is well attested in sources contemporaneous with his reign. Beyond his pyramid complex, he is mentioned in the tomb of many of his contemporaries such as his vizier Washptah, the courtier Rawer[23] and the priest Akhethetep.[24] Neferirkare also appears in the nearly contemporaneous Giza writing board, a short list grouping six kings from different dynasties dating to the later Fifth or early Sixth Dynasty.[25] The writing board was uncovered in the tomb of a high official named Mesdjerw, who may have composed it for his use in the afterlife.[26]

Historical sources

Neferirkare is attested in two ancient Egyptian king lists, both dating to the New Kingdom. The earliest of these is the Abydos King List written during the reign of Seti I (fl. 1290–1279 BCE). There, Neferirkare's nomen "Kakai" occupies the 28th entry, in between those of Sahure and Neferefre. During the subsequent reign of Ramesses II (fl. 1279–1213 BCE), Neferirkare's prenomen was recorded on the 27th entry of the Saqqara Tablet, but this time as a successor of Sahure and predecessor of Shepseskare.[27]

Neferirkare was also given an entry in the Turin canon, a document dating to the reign of Ramesses II as well. Neferirkare's entry is commonly believed to be in the third column-19th row; unfortunately this line has been lost in a large lacuna affecting the papyrus, and neither his reign length nor his successor can be ascertained from the surviving fragments. The Egyptologist Miroslav Verner has furthermore proposed that the Turin canon makes a new dynasty start with this entry and thus that Neferirkare would be its founder.[28][29][30] The division of the Turin canon list of kings into dynasties is a currently debated topic. The Egyptologist Jaromír Málek, for example, sees the divisions between groups of kings occurring in the canon as marking transfers of royal residence rather than the rise and fall of royal dynasties, as this term is currently understood. That usage only began in the Egyptian context with the 3rd-century BCE work of the priest Manetho.[31] Similarly, the Egyptologist Stephan Seidlmeyer, considers the break in the Turin Canon at the end of the Eighth Dynasty to represent the relocation of the royal residence from Memphis to Herakleopolis.[32] The Egyptologist John Baines holds views that are closer to Verner's, believing that the canon was divided into dynasties, with totals for the time elapsed given at the end of each, though only a few such divisions have survived.[33] Similarly, Professor John Van Seters views the breaks in the canon as divisions between dynasties, but in contrast, states that the criterion for these divisions remains unknown. He speculates that the pattern of dynasties may have been taken from the nine divine kings of the Greater and Lesser Enneads.[34] The Egyptologist Ian Shaw believes that the Turin Canon gives some credibility to Manetho's division of dynasties, but considers the king lists to be a form of ancestor worship and not a historical record.[35] This whole problem could be mooted by another of Verner's speculations, where he proposes that Neferirkare's entry may have been located on the 20th line rather than the 19th, as is usually believed. This would credit Neferirkare with a seven-year reign,[29] and would make Sahure the dynasty founder, according to the hypothesis that the canon records such events. Archaeological evidence has established that the transitions from Userkaf to Sahure and from Sahure to Neferirkare were father–son transitions, so that neither Sahure nor Neferirkare can be dynasty founders in the modern sense of the term.[36][37]

Neferirkare was mentioned in the Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BCE during the reign of Ptolemy II (283–246 BCE) by Manetho. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived to this day and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius. The Byzantine scholar George Syncellus reports that Africanus relates that the Aegyptiaca mentioned the succession "Sephrês → Nefercherês → Sisirês" for the early Fifth Dynasty. Sephrês, Nefercherês and Sisirês are believed to be the hellenized forms for Sahure, Neferirkare and Shepseskare, respectively. Thus, Manetho's reconstruction of the Fifth Dynasty is in agreement with the Saqqara tablet.[38] In Africanus' epitome of the Aegyptiaca, Nefercherês is reported to have reigned for 20 years.[39]

Family

Parents and siblings

Until 2005, the identity of Neferirkare's parents was uncertain. Some Egyptologists, including Nicolas Grimal, William C. Hayes, Hartwig Altenmüller, Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton, viewed him as a son of Userkaf and Khentkaus I, and a brother to his predecessor Sahure.[5][41][42][43][44] The main impetus behind this theory was the Westcar Papyrus, an Ancient Egyptian story narrating the rise of the Fifth Dynasty. In it, a magician prophesizes to Khufu that the future demise of his lineage will be in the form of three brothers – the first three kings of the Fifth Dynasty, born of the god Ra and a woman named Rededjet.[45] Egyptologists such as Verner have sought to discern a historical truth in this account, proposing that Sahure and Neferirkare were siblings born of queen Khentkaus I.[note 2][47]

In 2005, excavations of the causeway leading up to Sahure's pyramid yielded new relief fragments which showed indisputably that pharaoh Sahure and his consort, queen Meretnebty, were Neferirkare's parents. Indeed, these reliefs—discovered by Verner and Tarek El Awady—depict Sahure and Meretnebty together with their two sons, Ranefer and Netjerirenre.[36] While both sons are given the title of "king's eldest son", possibly indicating that they were twins,[49] Ranefer is shown closer to Sahure and also given the title of "chief lector-priest", which may reflect that he was born first and thus given higher positions.[50] Since Ranefer is known to have been the name of Neferirkare before he took the throne, as indicated by reliefs from the mortuary temple of Sahure (see below), no doubt remains as to Neferirkare's filiation.[36] Nothing more is known about Netjerirenre, an observation which has led Verner and El-Awady to speculate that he could have attempted to seize the throne upon the unexpected death of Neferirkare's son and successor Neferefre, who died in his early twenties after two years on the throne. In this conjectural hypothesis, he would be the ephemeral Shepseskare.[51][50] Finally, the same relief, as well as an additional one, record a further four sons of Sahure – Khakare,[52] Horemsaf,[53] Raemsaf and Nebankhre. The identity of their mother(s) is unknown,[54] so they are, at minimum, half-brothers to Neferirkare.[55]

|

|

|

|

| |

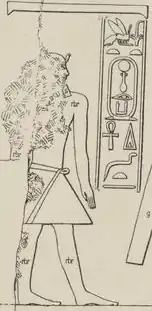

| Fragments of reliefs from the mortuary temple of Sahure showing Neferirkare as a prince. The reliefs were altered during the latter's reign with the addition of royal titles and regalia.[56][57] | ||

Consort and children

As of the early 21st century, the only known queen of Neferirkare is Khentkaus II. This is due to the position of her pyramid next to that of Neferirkare as was normal for the consort of a king, as well as her title of "king's wife" and several reliefs representing both of them together.[58] Neferirkare could possibly have had at least one other spouse, as suggested by the presence of a small pyramid next to that of Khentkaus, but this remains conjectural.[57]

Neferirkare and his consort Khentkaus II were, in all likelihood, the parents of prince Ranefer B, the future pharaoh Neferefre.[4][59][60][61] This relationship is confirmed by a relief on a limestone slab discovered in a house in the village near Abusir[62] depicting Neferirkare and his wife Khentkaus with "the king's eldest son Ranefer",[note 3][63] a name identical with some variants of Neferefre's own.[64] This indicates that, just as for Neferirkare, Ranefer was Neferefre's name when he was still only a crown prince, that is, before his accession to the throne.[65]

Neferirkare and Khentkaus II had at least one other child together, the future pharaoh Nyuserre Ini.[61][66] Indeed, Neferirkare's consort Khentkaus II is known to have been Nyuserre's mother, since excavations of her mortuary temple yielded a fragmentary relief showing her facing Nyuserre and his family.[67][68][69] Remarkably, on this relief both Khentkaus and Nyuserre appear on the same scale,[68] an observation which may be connected with Khentkaus' enhanced status during Nyuserre's reign, as he sought to legitimise his rule following the premature death of Neferefre and the possible challenge by Shepseskare.[70][71] Further evidence for the filiation of Nyuserre are the location of his pyramid next to that of Neferirkare, as well as his reuse for his own valley temple of materials from Neferikare's unfinished constructions.[72]

Yet another son of Neferirkare and Khentkhaus has been proposed,[73] probably younger[74] than both Neferefre and Nyuserre: Iryenre, a prince iry-pat[note 4] whose relationship is suggested by the fact that his funerary cult was associated with that of his mother, both having taken place in the temple of Khentkaus II.[76][77]

Finally, Neferirkare and Khentkaus II may also be the parents of queen Khentkaus III,[78] whose tomb was discovered in Abusir in 2015. Indeed, based on the location and general date for her tomb, as well as her titles of "king's wife" and "king's mother", Khentkaus III was almost certainly Neferefre's consort[79] and the mother of either Menkauhor Kaiu or Shepseskare.[78]

Reign

Duration

Manetho's Aegyptiaca assigns Neferirkare a reign of 20 years, but the archaeological evidence now suggests that this is an overestimate. First, the damaged Palermo Stone preserves the year of the 5th cattle count for Neferirkare's time on the throne.[80] The cattle count was an important event aimed at evaluating the amount of taxes to be levied on the population. By the reign of Neferirkare, this involved counting cattle, oxen and small livestock.[81] This event is believed to have been biennial during the Old Kingdom period, that is occurring once every two years, meaning that Neferirkare reigned at least ten years. Given the shape of the Palermo stone, this record must correspond to his final year or be close to it,[82] so that he ruled no more than eleven years. This is further substantiated by two cursive inscriptions left by masons on stone blocks from the pyramids of Khentkaus II and Neferirkare, both of which also date to Neferirkare's fifth cattle count, its highest known regnal year.[80][83] Finally, Verner has pointed out that a 20-year-long reign would be difficult to reconcile with the unfinished state of his pyramid in Abusir.[84]

Activities in Egypt

Beyond his construction of a pyramid and sun temple, little is known of Neferirkare's activities during his time on the throne.[86] Some events dating to his first and final years of reign are recorded on the surviving fragments of the Palermo stone,[87][88][89] a royal annal covering the period from the start of the reign of Menes of the First Dynasty until around the time of Neferirkare's rule.[note 6][91][92] According to the Palermo stone, the future pharaoh Neferirkare, then called prince Ranefer,[note 7] ascended the throne the day after his father Sahure's death, which occurred on the 28th day of the ninth month.[94][95]

The annal then records that in his first year as king, Neferirkare granted land to the agricultural estates serving the cults of the Ennead, the Souls of Pe and Nekhen and the gods of Keraha.[note 8][97][49] To Ra and Hathor, he dedicated an offering table provided with 210 daily offerings, and ordered the construction of two store rooms and the employment of new dependents in the host temple.[97] Neferirkare also commanded "the fashioning and opening of the mouth of an electrum statue of [the god] Ihy, escorting [it] to the mrt-chapel of Snefru of the nht-shrine of Hathor".[98][99] Later in his reign, in the year of the fifth cattle count, Neferirkare had a bronze statue of himself erected and set up four barques for Ra and Horus in and around his sun temple, two of which were of copper. The Souls of Pe and Nekhen and Wadjet received electrum endowments, while Ptah was given lands.[100]

The fact that the Palermo stone terminates[90] around Neferirkare's rule led some scholars, such as Grimal, to propose that they might have been compiled during his reign.[86]

Administration

Few specific administrative actions taken by Neferirkare are known. One decree of his inscribed on a limestone slab was excavated in 1903 in Abydos and is now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.[15] The decree exempts personnel belonging to a temple of Khenti-Amentiu from undertaking compulsory labour in perpetuity, under penalty of forfeiture of all property and freedom and be forced to work the fields or in a stone quarry.[101][102][81] This decree indirectly suggests that taxation and compulsory labour was imposed on everybody as a general rule.[103]

More generally, Neferirkare's reign saw the growth of the Egyptian administration and priesthood, which amassed more power than in earlier reigns, although the king remained a living god.[4] In particular the positions of viziers and overseer of the expedition, that is the highest offices, were opened to people from outside the royal family.[89] In conjunction with this trend, the mastabas of high officials started to become more elaborate, with, for example, chapels including multiple rooms,[104][105] and from the mid to late Fifth Dynasty, wide entrance porticoes with columns[106] and family tomb complexes.[105] It is also at this time that these officials started to record autobiographies on the walls of their tombs.[60]

Modification of the royal titulary

The reign of Neferirkare Kakai saw the last[107] important modification to the titulary of pharaohs. He was the earliest pharaoh to separate the nswt-bjtj ("King of Upper and Lower Egypt") and Z3-Rˁ ("Son of Ra") epithets of the royal titulary. He associated these two epithets with two different, independent names: the prenomen and nomen, respectively. The prenomen or throne name, taken by the new king as he ascended the throne, was written in a cartouche immediately after the bee and sedge signs for nswt-bjtj.[107][108] From Neferirkare's time onwards,[109] the nomen, or birth name, was also written in a cartouche[110] systematically preceded by the glyphs for "Son of Ra", an epithet which had seen little use in preceding times.[41]

Trade and military activities

There is little evidence for military action during Neferirkare's reign. William C. Hayes proposed that a few fragmentary limestone statues of kneeling and bound prisoners of war discovered in his mortuary temple[111][112] possibly attest to punitive raids in Libya to the west or the Sinai and Canaan to the east during his reign.[41] The art historian William Stevenson Smith commented that such statues were customary[111] elements of the decoration of royal temples and mastabas, suggesting that they may not be immediately related to actual military campaigns. Similar statues and small wooden figures of kneeling captives were discovered in the mortuary complexes of Neferefre,[113] Djedkare Isesi,[114] Unas,[115] Teti,[116] Pepi I[117] and Pepi II[111] as well as in the tomb of vizier Senedjemib Mehi.[118][119]

Trade relations with Nubia are the only ones attested to during Neferirkare's reign.[60] The archaeological evidence for this are seal impressions and ostracon bearing his name uncovered in the fortress of Buhen, on the second cataract of the Nile.[120] Contacts with Byblos on the Levantine coast might also have happened during Neferirkare's rule, as suggested by a single alabaster bowl inscribed with his name unearthed there.[120]

Personality

Neferirkare's reign was unusual for the significant number of surviving contemporary records which describe him as a kind and gentle ruler. When Rawer, an elderly nobleman and royal courtier, was accidentally touched by the king's mace during a religious ceremony[11]—a dangerous situation which could have caused this official to be put immediately to death[60] or banished from court since the pharaoh was viewed as a living god in Old Kingdom mythology—Neferirkare quickly pardoned Rawer and commanded that no harm should occur to the latter for the incident.[121][122] As Rawer gratefully states in an inscription from his Giza tomb:

Now the priest Rawer in his priestly robes was following the steps of the king in order to conduct the royal costume, when the sceptre in the king's hand struck the priest Rawer's foot. The king said, "You are safe". So the king said, and then, "It is the king's wish that he be perfectly safe, since I have not struck at him. For he is more worthy before the king than any man."[23][123][124]

Similarly, Neferirkare gave the Priest of Ptah Ptahshepses the unprecedented honour of kissing his feet[11][125] rather than the ground in front of him.[126] Finally, when the vizier Washptah suffered a stroke while attending court, the king quickly summoned the palace's chief doctors to treat his dying vizier.[11] When Washptah died, Neferirkare was reportedly inconsolable and retired to his personal quarters to mourn the loss of his friend. The king then ordered the purification of Washptah's body in his presence and ordered an ebony coffin made for the deceased vizier. Washptah was buried with special endowments and rituals courtesy of Neferirkare.[127] The records of the king's actions are inscribed in Washptah's tomb itself[128] and emphasize Neferirkare's humanity towards his subjects.[129]

Building activities

Pyramid complex

Pyramid

The Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai, known to the Ancient Egyptians as Ba-Neferirkare and variously translated as "Neferirkare is a Ba"[130] or "Neferirkare takes form",[5] is located in the royal necropolis of Abusir.[131] It is the largest one built during the Fifth Dynasty, equalling roughly the size of the Pyramid of Menkaure.[5] Workers and artisans who built the pyramid and its surrounding complex lived in pyramid town "Neferirkare-is-the-soul" or "Kakai-is-the-soul", located in Abusir.[132]

The pyramid construction comprised three stages:[133] first built were six steps[28] of rubble, their retaining walls made of locally quarried limestone[134] indicating that the monument was originally planned to be a step pyramid,[135][136] an unusual design for the time which had not been used since the Third Dynasty, some 120 years earlier.[28] At this point the pyramid, had it been completed, would have reached 52 m (171 ft).[28] This plan was then altered by a second construction stage with the addition of filling between the steps meant to transform the monument into a true pyramid.[136] At a later stage, the workers enlarged the pyramid further, adding a girdle of masonry and smooth casing stones of red granite.[136] This work was never finished,[135] even after the works implemented by Nyuserre.[137] With a square base of 108-metre-long (354 ft) sides,[138] the pyramid would have reached 72 m (236 ft) high had it been completed.[28] Today it is in ruins owing to extensive stone robbing.[139] The entrance to the pyramid's substructures was located on its north side. There, a descending corridor with a gable roof made of limestone beams led into a burial chamber. No pieces of the sarcophagus of the king were found there.[136]

The pyramid of Neferirkare is surrounded by smaller pyramids and tombs which seem to form an architectural unit, the cemetery of his close family.[28] This ensemble was meant to be reached from the Nile via a causeway and a valley temple near the river. At the death of Neferirkare, only the foundations of both had been laid and Nyuserre later diverted the unfinished causeway to his own pyramid.[136]

Mortuary temple

The mortuary temple was far from finished at the death of Neferirkare but it was completed later, by his sons Neferefre and Nyuserre Ini using cheap mudbricks and wood rather than stone.[140] A significant cache of administrative papyri, known as the Abusir papyri, was uncovered there by illegal diggers in 1893 and subsequently by Borchardt in 1903.[141] Further papyri were also uncovered in the mid-seventies during a University of Prague Egyptological Institute excavation.[86] The presence of this cache is due to the peculiar historical circumstances of the mid-Fifth Dynasty.[142] As both Neferirkare and his heir Neferefre died before their pyramid complexes could be finished, Nyuserre altered their planned layout, diverting the causeway leading to Neferirkare's pyramid to his own. This meant that Neferefre's and Neferirkare's mortuary complexes became somewhat isolated on the Abusir plateau, their priests therefore had to live next to the temple premises in makeshift dwellings,[143] and they stored the administrative records onsite.[142] In contrast, the records of other temples were kept in the pyramid town close to Sahure's or Nyuserre's pyramid, where the current level of ground water means any papyrus has long since disappeared.[144]

The Abusir papyri record some details pertaining to Neferirkare's mortuary temple. Its central chapel housed a niche with five statues of the king. The central one is described in the papyri as being a representation of the king as Osiris, while the first and last ones depicted him as the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, respectively.[145][146] The temple also comprised store-rooms for the offerings, where numerous stone vessels—now broken—had been deposited.[147] Finally the papyri indicate that of the four boats included in the mortuary complex, two were buried to the north and south of the pyramid, one of which was unearthed by Verner.[148]

During the Late Period of ancient Egypt (664–332 BCE) the mortuary temple of Neferirkare was used as a secondary cemetery. A gravestone made of yellow calcite was discovered by Borchardt bearing an Aramaic inscription reading "Belonging to Nesneu, son of Tapakhnum".[149] Another inscription[150] in Aramaic found on a limestone block and dating to the fifth century BCE reads "Mannukinaan son of Sewa".[151]

Sun temple

Neferirkare is known from ancient sources to have built a temple to the sun god Ra, which is yet to be identified archaeologically.[5] It was called Setibre,[note 9] meaning "Site of the heart of Ra",[5] and was, according to contemporary sources, the largest one built during the Fifth Dynasty.[4] It is possible that the temple was only built out of mudbricks, with a planned completion in stone which had not started when Neferirkare died. In this case, it would rapidly have turned into ruins that would be very difficult to locate for archaeologists.[153] Alternatively, the Egyptologist Rainer Stadelmann has proposed that the Setibre as well as the sun temples of Sahure and Userkaf were one and the same known building, that attributed to Userkaf in Abusir.[154] This hypothesis has been dispelled in late 2018 thanks to advanced analyses of the verso of the Palermo stone by the Czech Institute of Archeology, which enabled the reading of inscriptions mentioning precisely the architecture of the temple as well as lists of donations it received.[155]

Of all the sun temples built during the Fifth Dynasty, the Setibre is the one most commonly cited in ancient sources. Due to this, some details of its layout are known: it had a large central obelisk, an altar and store-rooms, a sealed barque room housing two boats[148] and a "hall of the 'Sed festival'". Religious festivals did certainly take place in sun temples, as is attested to by the Abusir papyri. In the case of the Setibre, the festival of the "Night of Ra"[note 10] is specifically said to have taken place there.[157] This was a festival concerned with Ra's journey during the night and connected with the ideas of renewal and rebirth that were central to sun temples.[156]

The temple played an important role in the distribution of food offerings which were brought everyday from there to the mortuary temple of the king.[158][159][160] This journey was made by boat, indicating that the Setibre was not adjacent to Neferirkare's pyramid. This also underscores the dependent position of the king with respect to Ra, as offerings were made to the sun god and then to the deceased king.[158]

Sun temple of Userkaf

The Egyptologist Werner Kaiser proposed, based on a study of the evolution of the hieroglyph determinative for "sun temple", that Neferirkare completed the sun temple of Userkaf—known in Ancient Egyptian as Nekhenre[note 11]—sometime around the fifth cattle count of his reign.[162][163] This opinion is shared by the Egyptologists and archaeologists Ogden Goelet, Mark Lehner and Herbert Ricke.[164][161][165] In this hypothesis, Neferirkare would have provided the Nekhenre with its monumental obelisk of limestone and red granite.[166] Verner and the Egyptologist Paule Posener-Kriéger have pointed out two difficulties with the hypothesis. Firstly, it would imply a long interlude between the two phases of construction of Userkaf's temple: nearly 25 years between the erection of the temple and that of its obelisk. Secondly, they observe that both the pyramid and sun temple of Neferirkare were unfinished at his death, raising the question as to why the king would have devoted exceptional effort on a monument of Userkaf when his own still required substantial works to be completed.[167][168] Instead, Verner proposes that it was Sahure who finished the Nekhenre.[169]

Funerary cult

As with the other pharaohs of the Fifth Dynasty, Neferirkare was the object of a funerary cult after his death. Cylinder seals belonging to priests and priestesses serving in this cult attest his existence during the Old Kingdom period. For example, a black steatite seal, now in the Metropolitan Museum bears the inscription "Votary of Hathor and priestess of the good god Neferirkare, beloved of the gods".[170] Some of these officials had roles in the cults of several kings, as well as in their sun temples.[171] Offerings for the funerary cult of deceased rulers were provided by dedicated agricultural estates set up during the king's reign. A few of these are known for Neferirkare, including "The estate of Kakai (named) the i3gt of Kakai",[note 12] "Strong is the power of Kakai",[note 13] "The plantations of Kakai",[note 14] "Nekhbet desires that Kakai lives",[175] "Neferirkare is beloved of the ennead"[97] and "The mansion of the Ba of Neferirkare".[97]

Traces of the continued existence of the funerary cult of Neferirkare beyond the Old Kingdom period are scant. A pair of statues belonging to a certain Sekhemhotep were uncovered in Giza, one of which is inscribed with the standard Ancient Egyptian offering formula followed by "of the temple of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Neferirkare, true of voice".[176] The statues, which date to the early 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom period are the only archaeological evidence that Neferirkare's funerary cult still existed or had been revived around Abusir at the time,[177][178] albeit in a very limited form.[179][180]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ↑ Proposed dates for Neferirkare Kakai's reign: 2539–2527 BCE,[3] 2492–2482 BCE,[4][5][6][7] 2483–2463 BCE,[8] 2477–2467 BCE,[9] 2475–2455 BCE,[10][11] 2458–2438 BCE[12] 2446–2438 BCE,[13][14][15] 2416–2407 BCE,[16] 2415–2405 BCE.[17]

- ↑ In this theory, Khentkaus I possibly remarried Userkaf after the death of her first husband Shepseskaf[46] and became the mother of Sahure and his successor on the throne Neferirkare Kakai.[47] This theory is based on the fact that Khentkaus was known to have borne the title of mwt nswt bity nswt bity, which could be translated as "mother of two kings". Some Egyptologists have therefore proposed that Khentkaus was the mother of Sahure and the historical figure on which the Rededjet of the Westcar Papyrus is based.[48] Following the discoveries of Verner and El-Awady in Abusir this theory was abandoned and the role of Khentkaus has been re-appraised. In particular, it is now understood that there were two queens Khentkaus, both of whom may have bore two kings, the latest one being the mother of Neferefre and Nyuserre Ini. In addition, an ephemeral pharaoh Djedefptah may have ruled between Shepseskaf and Userkaf, further troubling the circumstances of the rise of the Fifth Dynasty.[46]

- ↑ The transliteration of the inscription is [zȝ-nswt] smsw Rˁ-nfr.[59]

- ↑ Often translated as "Hereditary prince" or "Hereditary noble" and more precisely "Concerned with the nobility", this title denotes a highly exalted position.[75]

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt, who discovered this heset vase, noticed that the vase was not functional, being of plain wood, plaster, mortar and with no cavity. Consequently, he hypothesised that the vase was meant to be used in funerary rituals as a symbol of the functioning vessels made of precious materials employed in the temple.[85]

- ↑ The surviving fragments of the annal likely date to the much later 25th Dynasty (fl. 760–656 BCE), but they were certainly copied or compiled from Old Kingdom sources.[90]

- ↑ Known in modern Egyptology as Ranefer A since pharaoh Neferefre was also called Ranefer before ascending the throne and is thus called Ranefer B.[93]

- ↑ Located in Heliopolis, Keraha was believed to be the site of the battle between Horus and Seth.[96]

- ↑ Or Setibrau, transliteration St-ib-Rˁ(.w) in Ancient Egyptian.[152]

- ↑ Ancient Egyptian transliteration Grḥ n Rˁ(.w).[156]

- ↑ Nḫn-Rˁ means "Stronghold of Ra".[161]

- ↑ Transliteration ḥwt K3k3i i3gt K3k3i.[172]

- ↑ Transliteration W3š-b3w-K3k3i.[173]

- ↑ Transliteration Šw-K3k3i, uncertain reading[174]

References

- ↑ Borchardt 1910, plates 33 and 34.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. 337.

- ↑ Hayes 1978, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 Verner 2001b, p. 589.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Altenmüller 2001, p. 598.

- ↑ Hawass & Senussi 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ El-Shahawy & Atiya 2005, p. 85.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. xxx.

- ↑ Clayton 1994, p. 60.

- ↑ Málek 2000a, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 Rice 1999, p. 132.

- ↑ von Beckerath 1999, p. 285.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. xx.

- ↑ MET 2002.

- 1 2 Decree of Neferirkare, BMFA 2017.

- ↑ Strudwick 1985, p. 3.

- ↑ Hornung 2012, p. 491.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Leprohon 2013, p. 39.

- ↑ Leprohon 2013, p. 39, footnote 52.

- ↑ Clayton 1994, p. 61.

- ↑ Leprohon 2013, p. 38.

- ↑ Scheele-Schweitzer 2007, pp. 91–94.

- 1 2 Allen et al. 1999, p. 396.

- ↑ de Rougé 1918, p. 81.

- ↑ Helck 1987, p. 117.

- ↑ Brovarski 1987, pp. 29–52.

- ↑ Mariette 1864, p. 4, plate 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 77.

- 1 2 Verner 2001a, p. 395.

- ↑ Verner 2000, p. 587.

- ↑ Málek 2004, p. 84, 103–104.

- ↑ Seidlmeyer 2004, p. 108.

- ↑ Baines 2007, p. 198.

- ↑ Seters 1997, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Shaw 2004, pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 3 El-Awady 2006, pp. 208–213.

- ↑ El-Awady 2006, pp. 192–198.

- ↑ Verner 2000, p. 581.

- ↑ Waddell 1971, p. 51.

- ↑ Burkard, Thissen & Quack 2003, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 Hayes 1978, p. 66.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, pp. 68, 72, 74.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica 2017.

- ↑ Lichteim 2000, pp. 215–220.

- 1 2 Hayes 1978, pp. 66–68, 71.

- 1 2 Rice 1999, p. 173.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 62.

- 1 2 Bárta 2017, p. 6.

- 1 2 Verner 2007.

- ↑ El-Awady 2006, pp. 213–214.

- ↑ Baud 1999b, p. 535.

- ↑ Baud 1999b, p. 521.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 62–69.

- ↑ El-Awady 2006, pp. 191–218.

- ↑ Borchardt 1913, Plate 17.

- 1 2 Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Lehner 2008, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 Verner 1985a, p. 282.

- 1 2 3 4 Altenmüller 2001, p. 599.

- 1 2 Rice 1999, p. 97.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 135.

- ↑ Posener-Kriéger 1976, vol. II, p. 530.

- ↑ Verner 1980b, p. 261.

- ↑ Verner 1985a, pp. 281–284.

- ↑ Baud 1999a, p. 335.

- ↑ Verner 1980a, p. 161, fig. 5.

- 1 2 Baud 1999a, p. 234.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 126.

- ↑ Roth 2001, p. 317.

- ↑ Nolan 2012, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Schmitz 1976, p. 29.

- ↑ Verner, Posener-Kriéger & Jánosi 1995, p. 171.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 27.

- ↑ Baud 1999b, p. 418, see n. 24.

- ↑ Verner, Posener-Kriéger & Jánosi 1995, p. 70.

- 1 2 Krejčí, Kytnarová & Odler 2015, p. 35.

- ↑ Krejčí, Kytnarová & Odler 2015, p. 34.

- 1 2 Verner 2001a, p. 393.

- 1 2 Katary 2001, p. 352.

- ↑ Daressy 1912, p. 176.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, pp. 394–395.

- 1 2 3 Allen et al. 1999, p. 345.

- 1 2 3 Grimal 1992, p. 77.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Wilkinson 2000, p. 179.

- 1 2 Altenmüller 2001, p. 597.

- 1 2 Bárta 2017, p. 2.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. 3.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 46.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Verner 2000, p. 590.

- ↑ Schäfer 1902, p. 38.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 79, footnote 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Strudwick 2005, p. 73.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 92.

- ↑ Sethe 1903, p. 247.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 74.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, pp. 98–101.

- ↑ Sethe 1903, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ Schneider 2002, p. 173.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. 34.

- 1 2 Brovarski 2001, p. 11.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 12.

- 1 2 Teeter 1999, p. 495.

- ↑ Gardiner 1961, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 89.

- ↑ Clayton 1994, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 Smith 1949, p. 58.

- ↑ Hayes 1978, p. 115.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, pp. 146–147, 148–149.

- ↑ Porter, Moss & Burney 1981, p. 424.

- ↑ Porter, Moss & Burney 1981, p. 421.

- ↑ Porter, Moss & Burney 1981, p. 394.

- ↑ Porter, Moss & Burney 1981, p. 422.

- ↑ Smith 1949, plates 126d & e; fig. 130b.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 158.

- 1 2 Baker 2008, p. 260.

- ↑ Hornung 1997, p. 288.

- ↑ Baer 1960, pp. 98, 292.

- ↑ Manley 1996, p. 28.

- ↑ Sethe 1903, p. 232.

- ↑ Verner 2001c, p. 269.

- ↑ Breasted 1906, p. 118.

- ↑ Breasted 1906, pp. 243–249.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Roccati 1982, pp. 108–111.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 115.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. 24.

- ↑ Verner 2012, p. 407.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 76.

- ↑ Lehner 1999, p. 784.

- 1 2 Verner 2001d, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lehner 2008, p. 144.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, p. 394.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 116.

- ↑ Leclant 1999, p. 865.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 39.

- 1 2 Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 169.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, pp. 79, 170.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, pp. 79, 169.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. 97.

- ↑ Posener-Kriéger 1976, pp. 502, 544–545.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. 125.

- 1 2 Altenmüller 2002, p. 270.

- ↑ Porten, Botta & Azzoni 2013, p. 55.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 93.

- ↑ Porten, Botta & Azzoni 2013, pp. 67–69.

- ↑ Janák, Vymazalová & Coppens 2010, p. 431.

- ↑ Verner 2005, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Stadelmann 2000, pp. 541–542.

- ↑ Czech Institute of Egyptology website 2018.

- 1 2 Janák, Vymazalová & Coppens 2010, p. 438.

- ↑ Posener-Kriéger 1976, pp. 116–118.

- 1 2 Janák, Vymazalová & Coppens 2010, p. 436.

- ↑ Posener-Kriéger 1976, pp. 259, 521.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. 350.

- 1 2 Lehner 2008, p. 150.

- ↑ Kaiser 1956, p. 108.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, p. 388.

- ↑ Goelet 1999, p. 86.

- ↑ Ricke, Edel & Borchardt 1965, pp. 15–18.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, pp. 387–389.

- ↑ Posener-Kriéger 1976, p. 519.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, pp. 388–389.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, p. 390.

- ↑ Hayes 1978, p. 72.

- ↑ Brooklyn Museum 2017.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 70.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, pp. 70, 152.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 152.

- ↑ Murray 1905, plate IX.

- ↑ Málek 2000b, p. 249.

- ↑ Morales 2006, p. 313.

- ↑ Bareš 1985, pp. 87–94.

- ↑ Bareš 1985, p. 93.

- ↑ Málek 2000b, pp. 246–248.

Sources

- Allen, James; Allen, Susan; Anderson, Julie; Arnold, Arnold; Arnold, Dorothea; Cherpion, Nadine; David, Élisabeth; Grimal, Nicolas; Grzymski, Krzysztof; Hawass, Zahi; Hill, Marsha; Jánosi, Peter; Labée-Toutée, Sophie; Labrousse, Audran; Lauer, Jean-Phillippe; Leclant, Jean; Der Manuelian, Peter; Millet, N. B.; Oppenheim, Adela; Craig Patch, Diana; Pischikova, Elena; Rigault, Patricia; Roehrig, Catharine H.; Wildung, Dietrich; Ziegler, Christiane (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6543-0. OCLC 41431623.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2002). "Funerary Boats and Boat Pits of the Old Kingdom" (PDF). In Coppens, Filip (ed.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2001. Vol. 70. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 269–290.

- Baer, Klaus (1960). Rank and Title in the Old Kingdom: The Structure of the Egyptian Administration in the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. OCLC 911725773.

- Baker, Darrell (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC. London: Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9.

- Bareš, Ladislav (1985). "Eine Statue des Würdenträgers Sachmethotep und ihre Beziehung zum Totenkult des Mittleren Reiches in Abusir". Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (in German). Berlin/Leipzig. 112 (1–2): 87–94. doi:10.1524/zaes.1985.112.12.87. S2CID 192097104.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2017). "Radjedef to the Eighth Dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

- Baines, John (2007). Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198152507.

- Baud, Michel (1999a). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 1 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/1 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Baud, Michel (1999b). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 2 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/2 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1910). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs S'aḥu-Re (Band 1): Der Bau: Blatt 1–15 (in German). Leipzig: Hinrichs. ISBN 978-3-535-00577-1.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1913). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs S'aḥu-Re (Band 2): Die Wandbilder: Abbildungsblätter (in German). Leipzig: Hinrichs. OCLC 310832679.

- Breasted, James Henry (1906). Ancient records of Egypt; historical documents from the earliest times to the Persian conquest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 3931162.

- Brovarski, Edward (1987). "Two Old Kingdom writing boards from Giza". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Cairo. 71: 29–52.

- Brovarski, Edward (2001). Der Manuelian, Peter; Simpson, William Kelly (eds.). The Senedjemib Complex, Part 1. The Mastabas of Senedjemib Inti (G 2370), Khnumenti (G 2374), and Senedjemib Mehi (G 2378). Giza Mastabas. Vol. 7. Boston: Art of the Ancient World, Museum of Fine Arts. ISBN 978-0-87846-479-1.

- Burkard, Günter; Thissen, Heinz Josef; Quack, Joachim Friedrich (2003). Einführung in die altägyptische Literaturgeschichte. Band 1: Altes und Mittleres Reich. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie. Vol. 1, 3, 6. Münster: LIT. ISBN 978-3-82-580987-4.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- Collection of the Brooklyn Museum (2017). "Cylinder seal 44.123.30".

- Czech Institute of Egyptology website (1 October 2018). "New research and insights into the Palermo Stone". cegu.ff.cuni.cz. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Daressy, Georges (1912). "La Pierre de Palerme et la chronologie de l'Ancien Empire". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale (in French). 12: 161–214.

- "Decree of Neferirkare, catalog number 03.1896". Boston Museum of Fine Arts (BMFA). 2017.

- de Rougé, Emmanuel (1918). Maspero, Gaston; Naville, Édouard (eds.). Œuvres diverses, volume 6 (PDF). Bibliothèque Egyptologique (in French). Vol. 26. Paris: Ernest Leroux. OCLC 369027133.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- El-Awady, Tarek (2006). "The royal family of Sahure. New evidence." (PDF). In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2011.

- El-Shahawy, Abeer; Atiya, Farid (2005). The Egyptian Museum in Cairo: a walk through the alleys of ancient Egypt. Cairo: Farid Atiya Press. ISBN 978-9-77-172183-3.

- Gardiner, Alan Henderson (1961). Egypt of the Pharaohs: An Introduction. Galaxy books. Vol. 165. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-500267-6.

- Goelet, Ogden (1999). "Abu Gurab". In Bard, Kathryn; Shubert, Stephen Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Hawass, Zahi; Senussi, Ashraf (2008). Old Kingdom Pottery from Giza. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-305-986-6.

- Hayes, William (1978). The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 7427345.

- Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2002). "List of Rulers of Ancient Egypt and Nubia".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Helck, Wolfgang (1987). Untersuchungen zur Thinitenzeit. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen. Vol. 45. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-44-702677-2.

- Hornung, Erik (1997). "The pharaoh". In Donadoni, Sergio (ed.). The Egyptians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22-615556-2.

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David, eds. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5. ISSN 0169-9423.

- Janák, Jiří; Vymazalová, Hana; Coppens, Filip (2010). "The Fifth Dynasty 'sun temples' in a broader context". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010. Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts. pp. 430–442.

- Kaiser, Werner (1956). "Zu den Sonnenheiligtümern der 5. Dynastie". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. 14: 104–116.

- Katary, Sally (2001). "Taxation". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 351–356. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Krejčí, Jaromír; Kytnarová, Katarína Arias; Odler, Martin (2015). "Archaeological excavation of the mastaba of Queen Khentkaus III (tomb AC 30) in Abusir". Prague Egyptological Studies. Czech Institute of Egyptology. XV: 28–42.

- Leclant, Jean (1999). "Saqqara, pyramids of the 5th and 6th Dynasties". In Bard, Kathryn; Shubert, Stephen Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 865–868. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Lehner, Mark (1999). "Pyramids (Old Kingdom), construction of". In Bard, Kathryn; Shubert, Stephen Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 778–786. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The great name: ancient Egyptian royal titulary. Writings from the ancient world, no. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

- Lichteim, Miriam (2000). Ancient Egyptian Literature: a Book of Readings. The Old and Middle Kingdoms, Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02899-9.

- Málek, Jaromír (2000a). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2160–2055 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Málek, Jaromír (2000b). "Old Kingdom rulers as "local saints" in the Memphite area during the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 241–258. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Málek, Jaromír (2004). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2160 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–107. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Manley, Bill (1996). The Penguin historical atlas of ancient Egypt. London, New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051331-8.

- Mariette, Auguste (1864). "La table de Saqqarah". Revue Archéologique (in French). Paris: Didier. 10: 168–186. OCLC 458108639.

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27–July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4.

- Murray, Margaret Alice (1905). Saqqara Mastabas. Part I (PDF). Egyptian research account, 10th year. London: Bernard Quaritch. OCLC 458801811.

- "Neferirkare". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Nolan, John (2012). "Fifth Dynasty Renaissance at Giza" (PDF). AERA Gram. Vol. 13, no. 2. Boston: Ancient Egypt Research Associates. ISSN 1944-0014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Porten, Bezalel; Botta, Alejandro; Azzoni, Annalisa (2013). In the shadow of Bezalel : Aramaic, biblical, and ancient Near Eastern studies in honor of Bezalel Porten. Culture and history of the ancient Near East. Vol. 60. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00-424083-4.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind L. B.; Burney, Ethel W. (1981). Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, reliefs, and paintings. III/1. Memphis. Abû Rawâsh to Abûṣîr (PDF) (second, revised and augmented by Jaromír Málek ed.). Oxford: Griffith Institute, Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-900416-19-4.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule (1976). Les archives du temple funéraire de Neferirkare-Kakai (Les papyrus d'Abousir). Tomes I & II (complete set). Traduction et commentaire. Bibliothèque d'études (in French). Vol. 65. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. OCLC 4515577.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who is who in Ancient Egypt. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-44328-6.

- Ricke, Herbert; Edel, Elmar; Borchardt, Ludwig (1965). Das Sonnenheiligtum des Königs Userkaf. Band 1: Der Bau. Beiträge zur Ägyptischen Bauforschung und Altertumskunde (in German). Vol. 7. Cairo: Schweizerisches Institut für Ägyptische Bauforschung und Altertumskunde. OCLC 163256368.

- Roccati, Alessandro (1982). La Littérature historique sous l'ancien empire égyptien. Littératures anciennes du Proche-Orient (in French). Vol. 11. Paris: Editions du Cerf. ISBN 978-2-204-01895-1.

- Roth, Silke (2001). Die Königsmütter des Alten Ägypten von der Frühzeit bis zum Ende der 12. Dynastie. Ägypten und Altes Testament (in German). Vol. 46. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-04368-7.

- Schäfer, Heinrich (1902). Borchardt, Ludwig; Sethe, Kurt (eds.). Ein Bruchstück altägyptischer Annalen (in German). Berlin: Verlag der Königl. Akadamie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 912724377.

- Scheele-Schweitzer, Katrin (2007). "Zu den Königsnamen der 5. und 6. Dynastie". Göttinger Miszellen (in German). Göttingen: Universität der Göttingen, Seminar für Agyptologie und Koptologie. 215: 91–94. ISSN 0344-385X.

- Schmitz, Bettina (1976). Untersuchungen zum Titel s3-njśwt "Königssohn". Habelts Dissertationsdrucke: Reihe Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 2. Bonn: Habelt. ISBN 978-3-7749-1370-7.

- Schneider, Thomas (2002). Lexikon der Pharaonen (in German). Düsseldorf: Albatros. pp. 173–174. ISBN 3-491-96053-3.

- Seidlmeyer, Stephen (2004). "The First Intermediate Period (c. 2160–2055 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 108–136. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Seters, John Van (1997). In Search of History:Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History. Warsaw, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 1575060132.

- Sethe, Kurt Heinrich (1903). Urkunden des Alten Reichs (in German). wikipedia entry: Urkunden des Alten Reichs. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 846318602.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2004). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Smith, William Stevenson (1949). A History of Egyptian Sculpture and Painting in the Old Kingdom (second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. OCLC 558013099.

- Stadelmann, Rainer (2000). "Userkaf in Sakkara und Abusir. Untersuchungen zur Thronfolge in der 4. und frühen 5. Dynastie". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000 (in German). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 529–542. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Strudwick, Nigel (1985). The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders (PDF). Studies in Egyptology. London; Boston: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0107-9.

- Strudwick, Nigel (2005). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Writings from the Ancient World (book 16). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-680-8.

- Teeter, Emily (1999). "Kingship". In Bard, Kathryn; Shubert, Stephen Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 494–498. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Verner, Miroslav (1980a). "Excavations at Abusir". Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. 107: 158–169. doi:10.1524/zaes.1980.107.1.158. S2CID 201699676.

- Verner, Miroslav (1980b). "Die Königsmutter Chentkaus von Abusir und einige Bemerkungen zur Geschichte der 5. Dynastie". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur (in German). 8: 243–268. JSTOR 25150079.

- Verner, Miroslav (1985a). "Un roi de la Ve dynastie. Rêneferef ou Rênefer ?". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 85: 281–284.

- Verner, Miroslav; Zemina, Milan (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Prague: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Verner, Miroslav; Posener-Kriéger, Paule; Jánosi, Peter (1995). Abusir III : the pyramid complex of Khentkaus. Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Prague: Universitas Carolina Pragensis: Academia. ISBN 978-80-200-0535-9.

- Verner, Miroslav (2000). "Who was Shepseskara, and when did he reign?". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 581–602. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální. 69 (3): 363–418.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001c). The Pyramids; The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-80-213935-1.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001d). "Pyramid". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 87–95. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2005). "Die Sonnenheiligtümer der 5. Dynastie". Sokar (in German). 10: 43–44.

- Verner, Miroslav (2007). "New Archaeological Discoveries in the Abusir Pyramid Field: Sahure's causeway". Archaeogate. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- Verner, Miroslav (2012). "Pyramid towns of Abusir". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 41: 407–410. JSTOR 41812236.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Münchner ägyptologische Studien (in German). Vol. 49. Mainz: Philip von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2591-2.

- Waddell, William Gillan (1971). Manetho. Loeb classical library, 350. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; W. Heinemann. OCLC 6246102.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2000). Royal annals of ancient Egypt : the Palermo Stone and its associated fragments. Studies in Egyptology. London: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-71-030667-8.

External links

Media related to Neferirkare Kakai at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Neferirkare Kakai at Wikimedia Commons