| Ptolemy II Philadelphus | |

|---|---|

Bust of Ptolemy II, National Archaeological Museum, Naples | |

| Pharaoh | |

King of the Ptolemaic Kingdom | |

| Reign | 28 March 284 – 28 January 246 BC |

| Predecessor | Ptolemy I |

| Successor | Ptolemy III |

| Consorts | Arsinoe I Arsinoe II |

| Children | With Arsinoe I: Ptolemy III Lysimachus Berenice, Queen of Syria With Bilistiche: Ptolemy Andromachou |

| Father | Ptolemy I |

| Mother | Berenice I |

| Born | c.309 BC Kos |

| Died | 28 January 246 BC (aged 62–63) |

| Dynasty | Ptolemaic dynasty |

Ptolemy II Philadelphus (Greek: Πτολεμαῖος Φιλάδελφος Ptolemaios Philadelphos, "Ptolemy, sibling-lover"; 309 – 28 January 246 BC) was the pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt from 284 to 246 BC. He was the son of Ptolemy I, the Macedonian Greek general of Alexander the Great who founded the Ptolemaic Kingdom after the death of Alexander, and Queen Berenice I, originally from Macedon in northern Greece.

During Ptolemy II's reign, the material and literary splendour of the Alexandrian court was at its height. He promoted the Museum and Library of Alexandria. In addition to Egypt, Ptolemy's empire encompassed much of the Aegean and Levant. He pursued an aggressive and expansionist foreign policy with mixed success. From 275 to 271 BC, he led the Ptolemaic Kingdom against the rival Seleucid Empire in the First Syrian War and extended Ptolemaic power into Cilicia and Caria, but lost control of Cyrenaica after the defection of his half-brother Magas. In the Chremonidean War (c. 267–261 BC), Ptolemy confronted Antigonid Macedonia for control of the Aegean and suffered serious setbacks. This was followed by a Second Syrian War (260–253 BC) against the Seleucid empire, in which many of the gains from the first war were lost.

Early life

Ptolemy II was the son of Ptolemy I and his third wife, Berenice I. He was born on the island of Kos in 309/308 BC, during his father's invasion of the Aegean in the Fourth Diadoch War. He had two full sisters, Arsinoe II and Philotera.[2][3] Ptolemy was educated by a number of the most distinguished intellectuals of the age, including Philitas of Cos and Strato of Lampsacus.[4][5]

Ptolemy II had numerous half-siblings.[6] Two of his father's sons by his previous marriage to Eurydice, Ptolemy Keraunos and Meleager, became kings of Macedonia.[7] The children by his mother Berenice's first marriage to Philip included Magas of Cyrene and Antigone, the wife of Pyrrhus of Epirus.[3]

At Ptolemy II's birth, his older half-brother Ptolemy Keraunos was the heir presumptive. As Ptolemy II grew older a struggle for the succession developed between them, which culminated in Ptolemy Keraunos' departure from Egypt around 287 BC. On 28 March 284 BC, Ptolemy I had Ptolemy II declared king, formally elevating him to the status of co-regent.[8][9]

In contemporary documents, Ptolemy is usually referred to as "King Ptolemy son of Ptolemy" to distinguish him from his father. The co-regency between Ptolemy II and his father continued until the latter's death in April–June 282 BC. One ancient account claims that Ptolemy II murdered his father, but other sources say that he died of old age, which is more likely given that he was in his mid-eighties.[10][9][notes 1]

Reign

%252C_da_hermitage.jpg.webp)

Arsinoe I and Arsinoe II

The fall-out from the succession conflict between Ptolemy II and Ptolemy Keraunos continued even after Ptolemy II's accession. The conflict was probably the reason why Ptolemy executed two of his brothers, probably full brothers of Keraunos, in 281 BC.[11][12][13] Keraunos himself had gone to the court of Lysimachus, who ruled Thrace and western Asia Minor following his expulsion from Egypt. Lysimachus' court was divided on the question of supporting Keraunos. On the one hand, Lysimachus himself had been married to Ptolemy II's full sister, Arsinoe II, since 300 BC. On the other hand, Lysimachus' heir, Agathocles, was married to Keraunos' full sister Lysandra. Lysimachus chose to support Ptolemy II and sealed that decision at some point between 284 and 281 BC by marrying his daughter Arsinoe I to Ptolemy II.[14]

Continued conflict over the issue within his kingdom led to the execution of Agathocles and the collapse of Lysimachus' kingdom in 281 BC. Around 279 BC, Arsinoe II returned to Egypt, where she clashed with her sister-in-law Arsinoe I. Some time after 275 BC, Arsinoe I was charged with conspiracy and exiled to Coptos. Probably in 273/2 BC, Ptolemy married his older sister, Arsinoe II. As a result, both were given the epithet "Philadelphoi" (Koinē Greek: Φιλάδελφοι "Sibling-lovers"). While sibling-marriage conformed to the traditional practice of the Egyptian pharaohs, it was shocking to the Greeks, who considered it incestuous. Sotades, a poet who mocked the marriage, was exiled and assassinated.[15] The marriage may not have been consummated, since it produced no children.[16] Another poet Theocritus defended the marriage by comparing it to the marriage of the gods Zeus and his older sister Hera.[17] The marriage provided a model which was followed by most subsequent Ptolemaic monarchs.[13]

The three children of Arsinoe I, who included the future Ptolemy III, seem to have been removed from the succession after their mother's fall.[18] Ptolemy II seems to have adopted Arsinoe II's son by Lysimachus, also named Ptolemy, as his heir, eventually promoting him to co-regent in 267 BC, the year after Arsinoe II's death. He retained that position until his rebellion in 259 BC.[19][notes 2] Around the time of the rebellion, Ptolemy II legitimised the children of Arsinoe I by having them posthumously adopted by Arsinoe II.[18]

Conflict with Seleucids and Cyrene (281–275 BC)

Ptolemy I had originally supported the establishment of his friend Seleucus I as ruler of Mesopotamia, but relations had cooled after the Battle of Ipsos in 301 BC, when both kings claimed Syria. At that time, Ptolemy I had occupied the southern portion of the region, Coele Syria, up to the Eleutherus river, while Seleucus established control over the territory north of that point. As long as the two kings lived, this dispute did not lead to war, but with the death of Ptolemy I in 282 and of Seleucus I in 281 BC that changed.

Seleucus I's son Antiochus I spent several years fighting to re-establish control over his father's empire. Ptolemy II took advantage of this to expand his realm at Seleucid expense. The acquisitions of the Ptolemaic kingdom at this time can be traced in epigraphic sources and seem to include Samos, Miletus, Caria, Lycia, Pamphylia, and perhaps Cilicia. Antiochus I acquiesced to these losses in 279 BC, but began to build up his forces for a rematch.[20]

Antiochus did this by pursuing ties with Ptolemy II's maternal half-brother, Magas, who had been governor of Cyrenaica since around 300 BC and had declared himself king of Cyrene sometime after Ptolemy I's death. Around 275 BC Antiochus entered into an alliance with Magas by marrying his daughter Apama to him.[21] Shortly thereafter, Magas invaded Egypt, marching on Alexandria, but he was forced to turn back when the Libyan nomads launched an attack on Cyrene. At this same moment, Ptolemy's own forces were hamstrung. He had hired 4,000 galatian mercenaries, but soon after their arrival the Gauls mutinied and so Ptolemy marooned them on a deserted island in the Nile where "they perished at one another's hands or by famine."[22] This victory was celebrated on a grand scale. Several of Ptolemy's contemporary kings had fought serious wars against Gallic invasions in Greece and Asia Minor, and Ptolemy presented his own victory as equivalent to theirs.[23][24][25]

Around this time Ptolemy was also ostensibly considering some military action in Pre-Islamic Arabia, and so sent Ariston to reconnoiter the western coast of Arabia.[26]

Invasion of Nubia (c. 275 BC)

Ptolemy clashed with the kingdom of Nubia, located to the south of Egypt, over the territory known as the Triakontaschoinos ('thirty-mile land'). This was the stretch of the Nile river between the First Cataract at Syene and the Second Cataract at Wadi Halfa (the whole area is now submerged under Lake Nasser). The region may have been used by the Nubians as a base for raids on southern Egypt.[27] Around 275 BC, Ptolemaic forces invaded Nubia and annexed the northern twelve miles of this territory, subsequently known as the Dodekaschoinos ('twelve-mile land').[28] The conquest was publicly celebrated in the panegyric court poetry of Theocritus and by the erection of a long list of Nubian districts at the Temple of Isis at Philae, near Syene.[29][30] The conquered territory included the rich gold mines at Wadi Allaqi, where Ptolemy founded a city called Berenice Panchrysus and instituted a large-scale mining programme.[31] The region's gold production was a key contributor to the prosperity and power of the Ptolemaic empire in the third century BC.[30]

First Syrian war (274–271 BC)

Probably in response to the alliance with Magas, Ptolemy declared war on Antiochus I in 274 BC by invading Seleucid Syria. After some initial success, Ptolemy's forces were defeated in battle by Antiochus and forced to retreat back to Egypt. Invasion was imminent and Ptolemy and Arsinoe spent the winter of 274/3 BC reinforcing the defences in the eastern Nile Delta. However, the expected Seleucid invasion never took place. The Seleucid forces were afflicted by economic problems and an outbreak of plague. In 271 BC, Antiochus abandoned the war and agreed to peace, with a return to the status quo ante bellum. This was celebrated in Egypt as a great victory, both in Greek poetry, such as Theocritus' Idyll 17 and by the Egyptian priesthood in the Pithom stele.[32]

Colonisation of the Red Sea

Ptolemy revived earlier Egyptian programmes to access the Red Sea. A canal from the Nile near Bubastis to the Gulf of Suez – via Pithom, Lake Timsah and the Bitter Lakes – had been dug by Darius I in the sixth century BC. However, by Ptolemy's time it had silted up. He had it cleared and restored to operation in 270/269 BC – an act which is commemorated in the Pithom Stele. The city of Arsinoe was established at the mouth of the canal on the Gulf of Suez. From there, two exploratory missions were sent down the east and west coasts of the Red Sea all the way down to the Bab-el-Mandeb. The leaders of these missions established a chain of 270 harbour bases along the coasts, some of which grew to be important commercial centres.[33]

Along the Egyptian coast, Philotera, Myos Hormos, and Berenice Troglodytica would become important termini of caravan routes running through the Egyptian desert and key ports for the Indian Ocean trade which began to develop over the next three centuries. Even further south was Ptolemais Theron (possibly located near the modern Port Sudan), which was used as a base for capturing elephants. The adults were killed for their ivory, the children were captured to be trained as war elephants.[34][35]

On the east coast of the sea, the key settlements were Berenice (modern Aqaba/Eilat)[36] and Ampelone (near modern Jeddah). These settlements allowed the Ptolemies access to the western end of the caravan routes of the incense trade, run by the Nabataeans, who became close allies of the Ptolemaic empire.[33]

Chremonidean war (267–261 BC)

Throughout the early period of Ptolemy II's reign, Egypt was the preeminent naval power in the eastern Mediterranean. The Ptolemaic sphere of power extended over the Cyclades to Samothrace in the northern Aegean. Ptolemaic naval forces even entered the Black Sea, waging a campaign in support of the free city of Byzantion.[37] Ptolemy was able to pursue this interventionist policy without any challenge because a long-running civil war in Macedon had left a power vacuum in the northern Aegean. This vacuum was threatened after Antigonus II firmly established himself as king of Macedon in 272 BC. As Antigonus expanded his power through mainland Greece, Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II positioned themselves as defenders of 'Greek freedom' from Macedonian aggression. Ptolemy forged alliances with the two most powerful Greek cities, Athens and Sparta.[38]

The Athenian politician Chremonides forged a further alliance with Sparta in 269 BC.[39] In late 268 BC, Chremonides declared war on Antigonus II. The Ptolemaic admiral Patroclus sailed into the Aegean in 267 BC and established a base on the island of Keos. From there, he sailed to Attica in 266 BC. The plan seems to have been for him to rendezvous with the Spartan army and then use their combined forces to isolate and expel the Antigonid garrisons at Sounion and Piraeus which held the Athenians in check. However, the Spartan army was unable to break through to Attica and the plan failed.[40][41] In 265/4 BC, the Spartan king Areus I once again tried to cross the Isthmus of Corinth and aid the beleaguered Athenians, but Antigonus II concentrated his forces against him and defeated the Spartans, with Areus himself among the dead.[42] After a prolonged siege, the Athenians were forced to surrender to Antigonus in early 261 BC. Chremonides and his brother Glaucon, who were responsible for the Athenian participation in the war, fled to Alexandria, where Ptolemy welcomed them into his court.[43]

Despite the presence of Patroclus and his fleet, it appears that Ptolemy II hesitated to fully commit himself to the conflict in mainland Greece. The reasons for this reluctance are unclear, but it appears that, especially in the last years of the war, Ptolemaic involvement was limited to financial support for the Greek city-states and naval assistance.[44][45] Gunther Hölb argues that the Ptolemaic focus was on the eastern Aegean, where naval forces under the command of Ptolemy II's nephew and co-regent Ptolemy took control of Ephesus and perhaps Lesbos in 262 BC.[38] The end of Ptolemaic involvement may be related to the Battle of Kos, whose chronology is much disputed by modern scholars. Almost nothing is known about the events of the battle, except that Antigonus II, although outnumbered, led his fleet to defeat Ptolemy's unnamed commanders. Some scholars, such as Hans Hauben, argue that Kos belongs to the Chremonidean War and was fought around 262/1 BC, with Patroclus in command of the Ptolemaic fleet. Others, however, place the battle around 255 BC, at the time of the Second Syrian War.[46][47][48]

The Chremonidean War and the Battle of Kos marked the end of absolute Ptolemaic thalassocracy in the Aegean.[47] The League of the Islanders, which had been controlled by the Ptolemies and used by them to manage the Cycladic islands seems to have dissolved in the aftermath of the war. However, the conflict did not mean the complete end of the Ptolemaic presence in the Aegean. On the contrary, the naval bases established during the war at Keos and Methana endured until the end of the third century BC, while those at Thera, and Itanos in Crete remained bulwarks of Ptolemaic sea power until 145 BC.[49]

Second Syrian war (260–253 BC)

Around 260 BC, war broke out once more between Ptolemy II and the Seleucid realm, now ruled by Antiochus II. The cause of this war seems to have been the two kings' competing claims to the cities of western Asia Minor, particularly Miletus and Ephesus. Its outbreak seems to be connected to the revolt of Ptolemy II's co-regent Ptolemy, who had been leading the Ptolemaic naval forces against Antigonus II. The younger Ptolemy and an associate took control of the Ptolemaic territories in western Asia Minor and the Aegean. Antiochus II took advantage of this upset to declare war on Ptolemy II and he was joined by the Rhodians.[50]

The course of this war is very unclear, with the chronological and causal relationship of events attested at different times and in different theatres being open to debate.[51]

- Between 259 and 255 BC, the Ptolemaic navy, commanded by Chremonides, was defeated in a sea battle at Ephesus. Antiochus II then took control of the Ptolemaic cities in Ionia: Ephesus, Miletus, and Samos. Epigraphic evidence shows that this was complete by 254/3 BC.[51]

- Ptolemy II himself invaded Syria in 257 BC. We do not know what the outcome of this invasion was. At the end of the war, Ptolemy had lost sections of Pamphylia and Cilicia, but none of the Syrian territory south of the Eleutheros River.[51]

- It is possible, but not certain, that Antigonus was still at war with Ptolemy II during this period and that his great naval victory over Ptolemy at the Battle of Kos (mentioned above) took place in 255 BC within the context of the Second Syrian War.[51]

In 253 BC, Ptolemy negotiated a peace treaty, in which he conceded large amounts of territory in Asia Minor to Antiochus. The peace was sealed by Antiochus' marriage to Ptolemy's daughter Berenice, which took place in 252 BC. Ptolemy presented large indemnity payments to the Seleucids as the dowry connected to this wedding.[52][51]

After the war was over, in July 253 BC Ptolemy travelled to Memphis. There he rewarded his soldiers by distributing large plots of land that had been reclaimed from Lake Moeris in the Fayyum to them as estates (kleroi). The area was established as a new nome, named the Arsinoite nome, in honour of the long-dead Arsinoe II.[53]

Later reign and death (252–246 BC)

After the Second Syrian War, Ptolemy refocused his attention on the Aegean and mainland Greece. Some time around 250 BC, his forces defeated Antigonus in a naval battle at an uncertain location.[54] In Delos, Ptolemy established a festival, called the Ptolemaia in 249 BC, which advertised continued Ptolemaic investment and involvement in the Cyclades, even though political control seems to have been lost by this time. Around the same time, Ptolemy was convinced to pay large subsidies to the Achaean League by their envoy Aratus of Sicyon. The Achaean League was a relatively small collection of minor city-states in the northwestern Peloponnese at this date, but with the help of Ptolemy's money, over the next forty years Aratus would expand the League to encompass nearly the whole of the Peloponnese and transform it into a serous threat to Antigonid power in mainland Greece.[55]

Also in the late 250s BC, Ptolemy renewed his efforts to reach a settlement with his brother Magas. It was agreed that Ptolemy II's heir, Ptolemy III, would marry Magas' sole child, Berenice.[56] On Magas' death in 250 BC, however, Berenice's mother Apame refused to honour the agreement and invited an Antigonid prince, Demetrius the Fair, to Cyrene to marry Berenice instead. With Apame's help, Demetrius seized control of the city, but he was assassinated by Berenice.[57] A republican government led by two Cyrenaeans named Ecdelus and Demophanes controlled Cyrene until Berenice married Ptolemy III in 246 BC after his accession to the throne.[55]

Ptolemy died on 28 January 246 BC and was succeeded by Ptolemy III without incident.[55][58]

Regime

Ruler cult

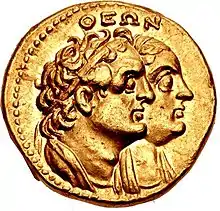

Ptolemy II was responsible for the transformation of the cult of Alexander the Great which had been established by Ptolemy I into a state cult of the Ptolemaic dynasty. At the start of his sole reign, Ptolemy II deified his father. He deified his mother Berenice I as well after her death in the 270s. The couple were worshipped as a pair, the Theoi Soteres (Saviour Gods). Around 272 BC, Ptolemy II promoted himself and his sister-wife Arsinoe II to divine status as the Theoi Adelphoi (Sibling Gods).

The eponymous priest of the deified Alexander, who served annually and whose name was used to date all official documents, became the 'Priest of Alexander and the Theoi Adelphoi'. Each subsequent royal couple would be added to the priest's title until the late second century BC. In artistic depictions, Ptolemy II was often depicted with divine attributes, namely the club of Heracles and the elephant-scalp headdress associated with Alexander the Great, while Arsinoe was shown carrying a pair of cornucopiae with a small ram's horn behind her ear.[59]

Ptolemy also instituted cults for a number of relatives. Following her death around 269 BC, Arsinoe II was honoured with a separate cult in her own right, with every temple in Egypt required to include a statue of her as a 'temple-sharing deity' alongside the sanctuary's main god. Her cult would prove extremely popular in Egypt throughout the Ptolemaic period. Ptolemy's other sister Philotera also received a cult. Even Ptolemy's mistress Bilistiche received sanctuaries in which she was identified with the goddess Aphrodite.[60][59]

A festival, called the Ptolemaia, was held in Ptolemy I's honour at Alexandria every four years from 279/278 BC. The festival provided an opportunity for Ptolemy II to showcase the splendour, wealth, and reach of the Ptolemaic empire. One of the Ptolemaia festivals from the 270s BC was described by the historian Callixenus of Rhodes and part of his account survives, giving a sense of the enormous scale of the event. The festival included a feast for 130 people in a vast royal pavilion and athletic competitions. The highlight was a Grand Procession, composed on a number of individual processions in honour of each of the gods, beginning with the Morning Star, followed by the Theoi Soteres, and culminating with the Evening Star. The procession for Dionysus alone contained dozens of festival floats, each pulled by hundreds of people, including a four-metre high statue of Dionysus himself, several vast wine-sacks and wine krateres, a range of tableaux of mythological or allegorical scenes, many with automata, and hundreds of people dressed in costume as satyrs, sileni, and maenads. Twenty-four chariots drawn by elephants were followed by a procession of lions, leopards, panthers, camels, antelopes, wild asses, ostriches, a bear, a giraffe and a rhinoceros.[61]

Most of the animals were in pairs - as many as eight pairs of ostriches - and although the ordinary chariots were likely led by a single elephant, others which carried a 7-foot-tall (2.1 m) golden statue may have been led by four.[62] At the end of the whole procession marched a military force numbering 57,600 infantry and 23,200 cavalry. Over 2,000 talents were distributed to attendees as largesse.

Although this ruler cult was centred on Alexandria, it was propagated throughout the Ptolemaic empire. The Nesiotic League, which contained the Aegean islands under Ptolemaic control, held its own Ptolemaia festival at Delos from the early 270s BC. Priests and festivals are also attested on Cyprus at Lapethos, at Methymna on Lesbos, on Thera, and possibly at Limyra in Lycia.

Pharaonic ideology and Egyptian religion

Ptolemy II followed the example of his father in making an effort to present himself in the guise of a traditional Egyptian pharaoh and to support the Egyptian priestly elite. Two hieroglyphic stelae commemorate Ptolemy's activities in this context. The Mendes stele celebrates Ptolemy's performance of rituals in honour of the ram god Banebdjedet at Mendes, shortly after his accession. The Pithom stele records the inauguration of a temple at Pithom by Ptolemy, in 279 BC on his royal jubilee. Both stelae record his achievements in terms of traditional Pharaonic virtues. Particularly stressed is the recovery of religious statuary from the Seleucids through military action in 274 BC – a rhetorical claim which cast the Seleucids in the role of earlier national enemies like the Hyksos, Assyrians, and Persians.[63]

As part of his patronage of Egyptian religion and the priestly elite, Ptolemy II financed large-scale building works at temples throughout Egypt. Ptolemy ordered the erection of the core of the Temple of Isis at Philae was erected in his reign and assigned the tax income from the newly conquered Dodekaschoinos region to the temple. Although the temple had existed since the sixth century BC, it was Ptolemy's sponsorship that converted it into one of the most important in Egypt.[64]

In addition, Ptolemy initiated work at a number of other sites, including (from north to south):

- Decorative work on the Temple of Anhur-Shu at Sebennytos and the nearby Temple of Isis at Behbeit El Hagar;[65][66]

- Temple of Horus at Tanis;[67]

- Temple of Arsinoe at Pithom;[68]

- Anubeion in the Serapeum at Saqqara;[65]

- Restoration of the Temple of Min at Akhmin;[69]

- Temple of Min and Isis at Koptos;[65][70]

- Expansion of the birth house of the Dendera Temple complex;[65]

- Decorative work on the Temple of Opet at Karnak and the north pylon of the Precinct of Mut at Karnak, Thebes.[65][71]

Administration

Ptolemaic Egypt was administered by a complicated bureaucratic structure. It is possible that much of the structure had already been developed in the reign of Ptolemy I, but evidence for it – chiefly in the form of documentary papyri – only exists from the reign of Ptolemy II. At the top of the hierarchy, in Alexandria, there were a small group of officials, drawn from the king's philoi (friends). These included the epistolographos ('letter-writer', responsible for diplomacy), the hypomnematographos ('memo-writer' or the chief secretary), the epi ton prostagmaton ('in charge of commands', who produced the drafts of royal edicts), the key generals, and the dioiketes ('household manager', who was in charge of taxation and provincial administration). The dioiketes for most of Ptolemy II's reign was Apollonius (262–245 BC). The enormous archive of his personal secretary, Zenon of Kaunos, happens to have survived. As a result, it is the administration of the countryside that is best known to modern scholarship.[72][73]

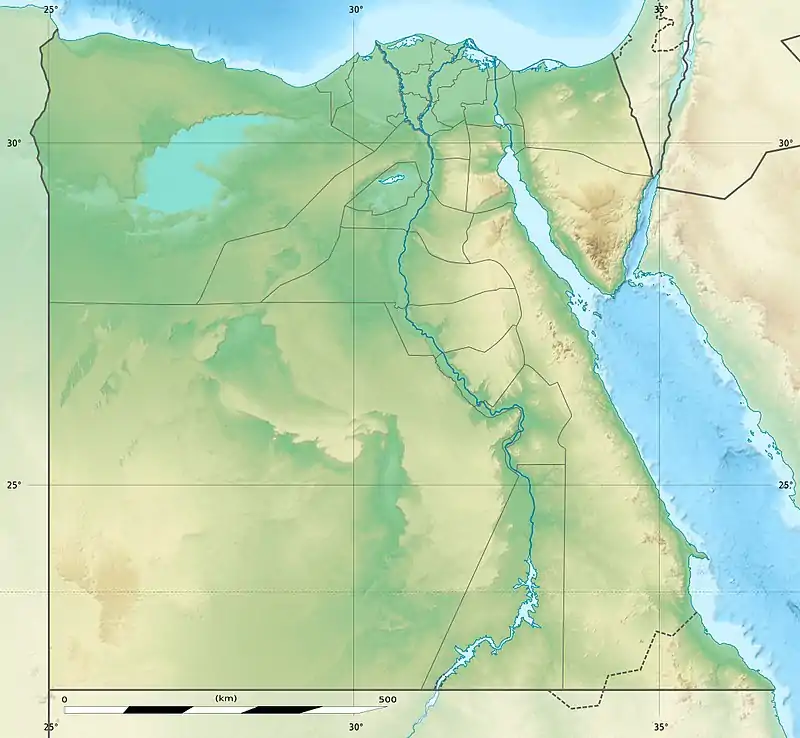

The whole of Egypt was divided into thirty-nine districts, called nomes (portions), whose names and borders had remained roughly the same since early Pharaonic times. Within each nome, there were three officials: the nomarch (nome-leader) who was in charge of agricultural production, the oikonomos (household steward) who was in charge of finances, and the basilikos grammateus (royal secretary), who was in charge of land surveying and record-keeping. All three of these officials answered to the dioiketes and held equal rank, the idea being that each would act as a check on the others and thus prevent officials from developing regional power bases that might threaten the power of the king. Each village had a komarch (village-leader) and a komogrammateus (village-secretary), who reported to the nomarch and the basilikos grammateus respectively.

Through this system, a chain of command was created which ran from the king all the way down to each of the three thousand villages of Egypt. Each nome also had its own strategos (general), who was in charge of the troops settled in the nome and answered directly to the king.[72][73]

A key goal of this administrative system was to extract as much wealth as possible from the land, so that it could be deployed for royal purposes, particularly war. It achieved this goal with greatest efficiency under Ptolemy II.[74]

Particular measures to increase efficiency and income are attested from the start of the Second Syrian War. A decree, known as the Revenue Laws Papyrus was issued in 259 BC to increase tax yields. It is one of our key pieces of evidence for the intended operation of the Ptolemaic tax system. The papyrus establishes a regime of tax farming (telonia) for wine, fruit, and castor oil. [74]

Private individuals paid the king a lump sum up front for the right to oversee the collection of the taxes (though the actual collection was carried out by royal officials). The tax farmers received any excess from the collected taxes as profit.[74]

This decree was followed in 258 BC by a 'General Inventory' in which the whole of Egypt was surveyed to determine the quantity of different types of land, irrigation, canals, and forests within the kingdom and the amount of income that could be levied from it.[74] Efforts were made to increase the amount of arable land in Egypt, particularly by reclaiming large amounts of land from Lake Moeris in the Fayyum. Ptolemy distributed this land to the Ptolemaic soldiers as agricultural estates in 253 BC.[74]

The Zenon papyri also record experiments by the dioiketes Apollonius to establish cash crop regimes, particularly growing castor oil, with mixed success. In addition to these measures focused on agriculture, Ptolemy II also established extensive gold mining operations, in Nubia at Wadi Allaqi and in the eastern desert at Abu Zawal.

Scholarship and culture

Ptolemy II was an eager patron of scholarship, funding the expansion of the Library of Alexandria and patronising scientific research. Poets like Callimachus, Theocritus, Apollonius of Rhodes, and Posidippus were provided with stipends and produced masterpieces of Hellenistic poetry, including panegyrics in honour of the Ptolemaic family. Other scholars operating under Ptolemy's aegis included the mathematician Euclid and the astronomer Aristarchus. Ptolemy is thought to have commissioned Manetho to compose his Aegyptiaca, an account of Egyptian history, perhaps intended to make Egyptian culture intelligible to its new rulers.[75]

A tradition preserved in the pseudepigraphical Letter of Aristeas presents Ptolemy as the driving force behind the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek as the Septuagint. This account contains several anachronisms and is unlikely to be true.[76] The Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible is likely to have taken place among the Jews of Alexandria, but the role of Ptolemy II is unclear and only the Pentateuch is likely to have been translated during his reign.[76][77]

Relations with the western Mediterranean

Ptolemy II and King Hiero II of Syracuse are regularly referred to as having enjoyed particularly close relations. There is substantial evidence for the exchange of goods and ideas between Syracuse and Alexandria. Hiero seems to have modelled various aspects of his royal self-representation and perhaps his tax system, the Lex Hieronica on Ptolemaic models. Two of the luminaries of Ptolemy II's court, the poet Theocritus and the mathematician and engineer Archimedes came from and eventually returned to Syracuse.[78] Numismatic evidence seems to indicate that Ptolemy II funded Hiero II's original rise to power – a series of Ptolemaic bronze coins known as the 'Galatian shield without Sigma' minted between 271 and 265 BC, have been shown to have been minted in Sicily itself, on the basis of their style, flan shape, die axes, weight and find spots. The first set seem to have been minted by a Ptolemaic mint, perhaps left there in 276 BC after Pyrrhus of Epirus' withdrawal from Sicily. They are succeeded by a series that seems to have been minted by the regular Syracusan mint, perhaps on the outbreak of the First Punic War in 265 BC.[79]

Ptolemy II cultivated good relations with Carthage, in contrast to his father, who seems to have gone to war with them at least once. One reason for this may have been the desire to outflank Magas of Cyrene, who shared a border with the Carthaginian empire at the Altars of Philaeni.[80] Ptolemy was also the first Egyptian ruler to enter into formal relations with the Roman Republic. An embassy from Ptolemy visited the city of Rome in 273 BC and established a relationship of friendship (Latin: amicitia).[81] These two friendships were tested in 264 BC, when the First Punic War broke out between Carthage and Rome, but Ptolemy II remained studiously neutral in the conflict, refusing a direct Carthaginian request for financial assistance.[82][80]

Relations with India

Ptolemy is recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court at Pataliputra in India,[83] probably to Emperor Ashoka:

"But [India] has been treated of by several other Greek writers who resided at the courts of Indian kings, such, for instance, as Megasthenes, and by Dionysius, who was sent thither by [Ptolemy II] Philadelphus, expressly for the purpose: all of whom have enlarged upon the power and vast resources of these nations." Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History", Chap. 21[84]

He is also mentioned in the Edicts of Ashoka as a recipient of the Buddhist proselytism of Ashoka:

Now it is conquest by Dhamma that Beloved-Servant-of-the-Gods considers to be the best conquest. And it [conquest by Dhamma] has been won here, on the borders, even six hundred yojanas away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni. Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika)

Marriages and issue

Ptolemy married Arsinoe I, daughter of Lysimachus, between 284 and 281 BC. She was the mother of his legitimate children:[85][58]

| Name | Image | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ptolemy III |  | c. 285–275 BC | October/December 222 BC | Succeeded his father as king in 246 BC. |

| Lysimachus | 221 BC | |||

| Berenice | c. 275 BC? | September/October 246 BC | Married the Seleucid king Antiochus II. |

Ptolemy II repudiated Arsinoe I in the 270s BC. Probably in 273 BC, he married his sister Arsinoe II, widow of Lysimachus. They had no offspring, but in the 260s BC, the children of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe I were legally declared to be Arsinoe II's children.[86]

Ptolemy II also had several concubines and mistresses, including Agathoclea (?), Aglais (?) daughter of Megacles, the cup-bearer Cleino, Didyme, the Chian harp player Glauce, the flautist Mnesis, the actress Myrtion, the flautist Pothine and Stratonice.[58] With a woman named Bilistiche he is said to have had an illegitimate son named Ptolemy Andromachou.[87]

See also

- Alexandrian Pleiad

- Library of Alexandria

- Ptolemaic period – period of Egyptian history during the Ptolemaic dynasty

- Ptolemais (disambiguation) – towns and cities named after members of the Ptolemaic dynasty

- Ancient Greece–Ancient India relations

Notes

- ↑ C. Bennett established the date of Ptolemy I's death in April–June. Previously, the standard date was January 282 BC, following A.E. Samuel Ptolemaic Chronology.

- ↑ This identification of Ptolemy son of Lysimachus, with Ptolemy "the son" who is attested as Ptolemy II's co-regent is argued in detail by Chris Bennett. Other scholars have identified the co-regent as the future Ptolemy III or some otherwise unknown son of Ptolemy II.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. SBL Press. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ↑ Clayman, Dee L. (2014). Berenice II and the Golden Age of Ptolemaic Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780195370881.

- 1 2 Berenice I Archived 17 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Livius.org; accessed 5 October 2021.

- ↑ Konstantinos Spanoudakis (2002). Philitas of Cos. Mnemosyne, Supplements, 229. Leiden: Brill. p. 29. ISBN 90-04-12428-4.

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 26

- ↑ Ogden, Daniel (1999). Polygamy Prostitutes and Death. The Hellenistic Dynasties. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. p. 150. ISBN 07156-29301.

- ↑ Macurdy, Grace Harriet (1985). Hellenistic Queens (Reprint of 1932 ed.). Ares Publishers. ISBN 0-89005-542-4.

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 24–5

- 1 2 Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy I". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ↑ Murder: Cornelius Nepos XXI.3; Illness: Justin 16.2.

- ↑ Pausanias 1.7.1

- ↑ Bennett, Chris. "Argaeus". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- 1 2 Hölbl 2001, p. 36

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 35

- ↑ Athenaeus Deipnosophistae 14.621a-b

- ↑ Scholia on Theocritus 17.128; Pausanias 1.7.3

- ↑ Theocritus Idyll 17

- 1 2 Bennett, Chris. "Arsinoe II". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ↑ Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy "the son"". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 38

- ↑ Pausanias 1.7.3

- ↑ Hinds, Kathryn (September 2009). Ancient Celts: Europe's Tribal Ancestors. Marshall Cavendish. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7614-4514-2.

- ↑ Pausanias 1.7.2; Callimachus Hymn 4.185-7, with Scholia

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 39

- ↑ Mitchell, Stephen (2003). "The Galatians: Representation and Reality". In Erskine, Andrew (ed.). A Companion to the Hellenistic World. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 280–293. ISBN 9780631225379.

- ↑ Tarn, W. W. "Ptolemy II and Arabia". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 15 (1): 9–25. doi:10.1177/030751332901500103. JSTOR 3854009.

- ↑ Referenced in a papyrus: SB 5111

- ↑ Agatharchides FGrH 86 F20; Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca 1.37.5

- ↑ Theocritus Idyll 17.87

- 1 2 Hölbl 2001, p. 55

- ↑ Diodorus, Bibliotheca 3.12; Pliny the Elder Natural History 6.170. Excavations of the city have been undertaken: Castiglioni, Alfredo; Castiglioni., Andrea; Negro, A. (1991). "A la recherche de Berenice Pancrisia dans le désert oriental nubien". Bulletin de la Société française d'égyptologie. 121: 5–24.

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 40

- 1 2 Hölbl 2001, p. 56

- ↑ Agatharchides F86; Strabo Geography 16.4.8; Pliny the Elder, Natural History 6.171

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 57

- ↑ Josephus Antiquities of the Jews 8.163–164

- ↑ Stephanus of Byzantium s.v. Ἄγκυρα; Dionysius of Byzantium, On the Navigation of the Bosporus 2.34.

- 1 2 Hölb 2001, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Byrne, Sean. "IG II3 1 912: Alliance between Athens and Sparta". Attic Inscriptions Online. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ↑ Hauben 2013

- ↑ O'Niel 2008, pp. 74–76

- ↑ O'Neil 2008, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Hölb 2001, p. 41

- ↑ Hauben 2013, p. 61.

- ↑ O'Neil 2008, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ O'Neil 2008, pp. 84–85.

- 1 2 Hauben 2013, p. 62.

- ↑ Hölb 2001, p. 44

- ↑ Hölb 2001, pp. 42–43

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 43–44

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hölbl 2001, p. 44

- ↑ Porphyry FGrH 260 F 43

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, p. 61

- ↑ Letter of Aristeas 180; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 12.93

- 1 2 3 Hölbl 2001, pp. 44–46

- ↑ Justin 26.3.2

- ↑ Justin 26.3.3–6; Catullus 66.25–28

- 1 2 3 Bennett, Chris. "Ptolemy II". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- 1 2 Holbl 2001, pp. 94–98

- ↑ Plutarch Moralia 753F

- ↑ Callixenus FGrH 627 F2 = Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, 5.196a-203be; detailed studies in: Rice, E. E. (1983). The grand procession of Ptolemy Philadelphus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. and Hazzard, R. A. (2000). Imagination of a monarchy : studies in Ptolemaic propaganda. University of Toronto Press. pp. 60–81. ISBN 9780802043139.

- ↑ Scullard, H.H The Elephant in the Greek and Roman World Thames and Hudson. 1974, pg 125 "At the head of an imposing array of animals (including...)"

- ↑ Holbl 2001, p. 81 & 84

- ↑ Holbl 2001, p. 86

- 1 2 3 4 5 Holbl 2001, pp. 86–87

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 105. ISBN 9780500283967.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 113. ISBN 9780500283967.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 111. ISBN 9780500283967.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 142. ISBN 9780500283967.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 151–152. ISBN 9780500283967.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 164. ISBN 9780500283967.

- 1 2 Hölbl 2001, pp. 58–59

- 1 2 Bagnall, Roger; Derow, Peter (2004). The Hellenistic Period: Historical Sources in Translation (2 ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell. pp. 285–288.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hölbl 2001, pp. 62–63

- ↑ Hölbl 2001, pp. 63–65

- 1 2 Gruen 2016, pp. 413–416.

- ↑ Dorival, 2021 & 14-17, 18.

- ↑ De Sensi Sestito, Giovanna (1995). "Rapporti tra la Sicilia, Roma e l'Egitto". In Caccamo Caltabiano, Maria (ed.). La Sicilia tra l'Egitto e Roma: la monetazione siracusana dell'età di Ierone II. Messina: Accademia peloritana dei pericolanti. pp. 38–44 & 63–64.

- ↑ Wolf, Daniel; Lorber, Catharine (2011). "The 'Galatian Shield without Σ' Series". The Numismatic Chronicle. 171: 7–57.

- 1 2 Holbl 2001, p. 54

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus Roman Antiquities 14.1; Livy Periochae 14.

- ↑ Appian Sicelica 1

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 38.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History", Chap. 21 Archived 28 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt". Ancient Egypt Online. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ Bennett, Chris. "Arsinoe II". Egyptian Royal Genealogy. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ↑ Ptolemy Andromachou by Chris Bennett

Bibliography

- Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicles of the Pharaohs: the reign-by-reign record of the rulers and dynasties of ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

- Dorival, Gilles (2021). The Septuagint from Alexandria to Constantinople : canon, New Testament, Church fathers, catenae (First ed.). Oxford. ISBN 9780192898098.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Grainger, John D. (2010). The Syrian Wars. pp. 281–328. ISBN 9789004180505.

- Gruen, Erich S. (2016). The Construct of Identity in Hellenistic Judaism Essays on Early Jewish Literature and History. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-037555-8. JSTOR j.ctvbkjxph.

- Hauben, Hans (2013). "Callicrates of Samos and Patroclus of Macedon, champions of Ptolemaic thalassocracy". In Buraselis, Kostas; Stefanou, Mary; Thompson, Dorothy J. (eds.). The Ptolemies, the Sea and the Nile: Studies in Waterborne Power. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–65. ISBN 9781107033351.

- Hazzard, R. A. (2000). Imagination of a Monarchy: Studies in Ptolemaic Propaganda. Toronto ; London: University of Toronto Press.

- Hölbl, Günther (2001). A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. London & New York: Routledge. pp. 143–152 & 181–194. ISBN 0415201454.

- Marquaille, Céline (2008). "The Foreign Policy of Ptolemy II". In McKechnie, Paul R.; Guillaume, Philippe (eds.). Ptolemy II Philadelphus and his World. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 39–64. ISBN 9789004170896.

- O'Neil, James L. (2008). "A Re-Examination of the Chremonidean War". In McKechnie, Paul R.; Guillaume, Philippe (eds.). Ptolemy II Philadelphus and his World. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 65–90. ISBN 9789004170896.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ptolemies". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 616–618.

External links

- Ptolemy Philadelphus at LacusCurtius — (Chapter III of E. R Bevan's House of Ptolemy, 1923)

- Ptolemy II Philadelphus entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- the Great Mendes Stele of Ptolemy II