| Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator | |

|---|---|

| Πτολεμαῖος Νέος Φιλοπάτωρ Pa netjer hunu meriyetef[1] | |

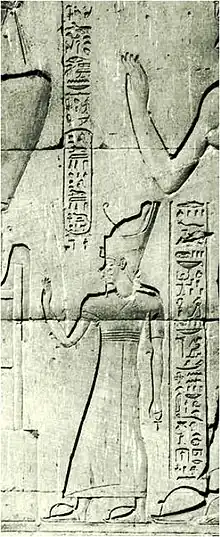

Ptolemy Memphites on a relief from the Temple of Edfu | |

| Pharaoh | |

| Coregency | Cleopatra II of Egypt? |

| Predecessor | Ptolemy VI Philometor? |

| Successor | Ptolemy VIII Physcon? |

| Father | Ptolemy VI Philometor or Ptolemy VIII Physcon |

| Mother | Cleopatra II of Egypt |

| Born | 2nd c. BC |

| Died | 2nd c. BC |

| Dynasty | Ptolemaic |

Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator[note 1] (Greek: Πτολεμαῖος Νέος Φιλοπάτωρ, Ptolemaĩos Néos Philopátōr "Ptolemy the Father-loving [God]") was, ostensibly, a Ptolemaic king of Egypt. His identity and reign are controversial, and it is likely that he did not reign at all, but was only granted royal dignity posthumously. Depending on the historical reconstruction, he was a son of Cleopatra II of Egypt by either Ptolemy VI Philometor or Ptolemy VIII Physcon, with current scholarship leaning toward the second option.[2]

Identity

The identity and role of the person usually designated Ptolemy Neos Philopator are unclear, and are based primarily on inferences from the succinct and possibly distorted information provided by Justin in his Epitome of the Philippic History of Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus.[3] Other relevant passages are found in Diodorus Siculus,[4] Josephus,[5] Livy,[6] and Orosius.[7]

Ptolemy, second son of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II

According to what used to be the dominant reconstruction, Ptolemy Neos Philopator was the second son of the siblings Ptolemy VI Philometor and Cleopatra II of Egypt, who reigned briefly with his father in 145 BC, and for a short time after his father's death, and was murdered by his uncle, Ptolemy VIII Physcon, when the latter married his mother Cleopatra II and became king of Egypt in 145 BC, as described by Justin.[8]

Reassessment

The identification described above had become traditional in scholarship for much of the 20th century, before being subjected to a fundamental challenge in a series of publications by Michel Chauveau.[9] Chauveau demonstrated that, while a second son of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II existed, born perhaps before 152 BC (when his older brother, Ptolemy Eupator, co-ruler in 152 BC, is described as their father's "eldest son"),[10] he was not associated on the throne with his father Ptolemy VI in 145 BC (the alleged evidence for that, a double dating of Year 36 = Year 1 in July-August 145 BC, is shown to reflect a brief parallel regnal count for Ptolemy VI as king in Syria[11]), and did not become king on his father's death later in 145 BC.[12] Moreover, Chauveau demonstrated that the surviving son of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II was not murdered on the return of Ptolemy VIII and his marriage to Cleopatra II in 145 BC, since he served as eponymous priest of Alexander and the dynastic cult in 143 BC.[13] Chauveau concluded that this Ptolemy, never king or co-ruler, was likely eliminated at a slightly later point, perhaps in relation to the birth of his half-brother Ptolemy Memphites, son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II in August 143 BC or the marriage between Ptolemy VIII and his niece Cleopatra III in 141 BC.[14] An alternative date for the elimination of the surviving son of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II is during the civil war of 132-127 BC, when Cleopatra II expelled Ptolemy VIII from Alexandria and he, according to Justin, summoned his eldest son (assuming this was actually his stepson) from Cyrene to Cyprus, where he had him executed, lest the Alexandrians proclaimed him king.[15] This reassessment of the evidence does not contradict the ancient sources, none of which explicitly states that the surviving son of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II became king, but it corrects Justin's assertion that he was eliminated on the occasion of his mother's marriage to Ptolemy VIII (likely inspired by a similar narrative about the marriage of Ptolemy Ceraunus to Arsinoe II[16]).

Ptolemy Memphites, only son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II

The reassessment of the evidence about the second son of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II has led to the alternative identification of Ptolemy Neos Philopator with Ptolemy Memphites, the son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II, who was born probably in August 143 BC, owing his by-name to his father's installation as pharaoh at the traditional capital Memphis at about the same time.[17] When Ptolemy VIII fled Alexandria in 132 BC, he took Ptolemy Memphites with him to Cyprus. According to Diodorus and Justin, here Ptolemy Memphites was murdered and dismembered on the orders of his father, who sent the remains of the boy to his mother Cleopatra II as a gruesome birthday gift. Subsequently, after the reconciliation between Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II in 124 BC, and in connection with the amnesty decrees of 118 BC, Ptolemy Memphites was integrated into the dynastic cult as Theos Neos Philopator ("the New Father-loving God").[18] Ptolemy Memphites, become Ptolemy Neos Philopator, was thus posthumously deified and added to the cult of the deified royals. But he had never been real king or co-ruler, except just possibly in absentia, if it really was the intention of his mother Cleopatra II of making him co-ruler.

Depictions

There are two preserved depictions of Ptolemy Memphites, on the western and eastern exteriors of the Naos of the Temple of Horus at Edfu. In these two parallel scenes, the god Thoth is represented offering eternity to the enthroned Ptolemy VIII Euergetes Physcon, behind whom stand the diminutive figure of a son, wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, and Cleopatra II, wearing a headdress with horns and tall plumes. The labels on the western exterior read: "The living ka of the King, the image of Swajba, the divine seed of the Lord of the Country, the King's Eldest Son, the King's Beloved, Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy, may he live forever, the Beloved of Ptah." The labels on the eastern exterior read: "Heir of the King, given birth by the Queen, who takes over from the Sole Lord, the King's Eldest Son, the King's Beloved, Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy, may he live forever, Beloved of Ptah, the God Euergetes." The heir, Ptolemy Memphites, is represented as king and his name is inscribed in a royal cartouche, although there is no attestation of any formal co-regency between him and his father. The epithet Euergetes is shared by all three royal figures, and is derived from the style of the senior king, Ptolemy VIII Euergetes Physcon. The reliefs representing Ptolemy Memphites are dated to 140 BC or a little earlier, long before his death and subsequent deification as Neos Philopator.[19]

Numbering

The now "traditional" numbering of the Ptolemies is based on a combination of the order of names in the Ptolemaic dynastic cult and the older historical reconstruction disproved by Chauveau. The numbering generally excludes co-rulers who did not become sole or senior monarchs, like Ptolemy "the Son", co-ruler, adopted son, and biological nephew of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, and Ptolemy Eupator, co-ruler and son of Ptolemy VI Philometor. The notion that Ptolemy Neos Philopator was the surviving son of Ptolemy VI Philometor and reigned in 145 BC, combined with his listing in the dynastic cult (in order of death and deification, not reign) before Ptolemy Euergetes Physcon, led to the numbering Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator and Ptolemy VIII Euergetes Physcon. This is certainly erroneous, as Ptolemy Euergetes Physcon had already come to the throne as co-ruler in 170 BC and as sole ruler in 164-163 BC, long before any of his nephews or sons could have done so. However, to avoid a potentially confusing renumbering of all Ptolemaic kings subsequent to Ptolemy VI, although Ptolemy Euergetes Physcon ought to be counted as Ptolemy VII, he is generally still labeled Ptolemy VIII.[20] Occasionally, the numbering is reversed, and Ptolemy VIII Physcon is numbered as Ptolemy VII, with the posthumously royal Ptolemy Neos Philopator (Memphites) numbered Ptolemy VIII, keeping subsequent regnal numbers unchanged. In some older works, Ptolemy Neos Philopator is omitted altogether; alternatively he is counted, as is Ptolemy Eupator. This results in the numbers 1 higher or 1 lower for the successors of Ptolemy VI. For these reasons, it is recommended that Ptolemaic kings be referenced alongside their epithets and nicknames, which provide less ambiguous identification.

Notes

- ↑ Numbering the Ptolemies is a modern convention. Older sources may give a number one higher or lower. The most reliable way of determining which Ptolemy is being referred to in any given case is by epithet (e.g. "Philopator").

References

- ↑ pɜ nṯr ḥwnw mrj-jt.f: Beckerath 1999: 238-239. The full style is not preserved.

- ↑ For both candidates, see Dodson and Hilton 2004: 268-269, 273, 280-281.

- ↑ Justin 38.8, translation by Yardley 1994: 243-244.

- ↑ Diodorus 33.6/61, 33.13, 33.20, 34/35.14, translation by Walton 1967: 18-19, 26-27, 36-39, 100-103.

- ↑ Josephus, Against Apion 2.49-53, translation by Thackeray 1926: 312-315

- ↑ Livy, Epitomes 52 and 59, translation by Schlesinger 1967: 43, 67.

- ↑ Orosius 5.10.6, translation by Fear 2010: 225-226.

- ↑ Gruen 1984: 712-714; Green 1990: 537, 544; Whitehorne 1994: 106-107; Ogden 1999: 86-87.

- ↑ Chauveau 1990, 1991, 2000.

- ↑ Chauveau 1990: 157; 2000: 258.

- ↑ Chauveau 1990: 146-153. This interpretation has gained wide acceptance, e.g., by Bennett, Lanciers 1995, and Hölbl 2001: 193-194.

- ↑ Chauveau 2000: 258-259. In fact, Chauveau 1990 and 1991 doubted the survival of any second son of Ptolemy VI or Cleopatra II, apart from the possibly illegitimate or pretended son propped up as king abroad by the Athamanian mercenary general Galaistes.

- ↑ Chauveau 2000: 257-258.

- ↑ Chauveau 2000: 259.

- ↑ Bielman 2017: 86, 95-98.

- ↑ As noted by Ogden 1999: 87.

- ↑ Chauveau 1990: 165; 2000: 259-261.

- ↑ Chauveau 1990: 155-156; Hölbl 2001: 202-203; Dodson and Hilton 2004: 268-269, 273, 280-281; Errington 2008: 298

- ↑ Cauville and Devauchelle 1984: 51-52, arguing that both reliefs represent Ptolemy Memphites, although some scholars thought only the eastern one did so; hieroglyphic texts in Chassinat 1929: 92, 229; photographs in Chassinat 1934, pl. 439 and 446.

- ↑ As recommended by Chauveau 1990: 165 n. 111; compare Errington 2008: 258.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

- Diodorus = Walton, F. R. (transl.), Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes, 12: Fragments of Books XXXIII-XL, Cambridge, MA, 1967.

- Josephus = Thackeray, H. S. J. (transl.), Josephus in Eight Volumes, 1: The Life; Against Apion, London, 1926.

- Justin = Yardley, J. C. (transl.), Justin: Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, Atlanta, 1994.

- Livy = Schlesinger, A. C. (transl.), Livy with an English Translation in Fourteen Volumes, 14: Summaries, Fragments, and Obsequens, Cambridge, MA, 1967.

- Orosius = Fear, A. T. (transl.), Orosius: Seven Books of History against the Pagans, Liverpool, 2010.

Secondary Literature:

- Beckerath, J. von, Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen, Mainz, 1999.

- Bielman, A., "Stéréotypes et réalités du pouvoir politique féminin: la guerre civile en Égypte entre 132 et 124 av. J.-C.," EuGeStA 7 (2017) 84-114.

- Chassinat, E., Le Temple d'Edfou 4, Cairo, 1929.

- Chassinat, E., Le Temple d'Edfou 13, Cairo, 1934.

- Chauveau, M., "Un été 145. Post-scriptum," BIFAO 90 (1990) 135-168. online

- Chauveau, M., "Un été 145.," BIFAO 91 (1991) 129-134. online

- Chauveau, M., "Encore Ptolémée «VII» et le dieu Neos Philopatôr!," Revue d’Égyptologie 51 (2000) 257-261.

- Cauville, S., and D. Devauchelle, "Le temple d'Edfou: étapes de la construction nouvelles données historiques," Revue d'Égyptologie 35 (1984) 31-55.

- Dodson, A., and D. Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, London, 2004.

- Errington, R. M., A History of the Hellenistic World 323-30 BC, Malden, MA, 2008.

- Green, P., From Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, Berkeley, 1990.

- Gruen, E., The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome, London, 1984.

- Hölbl, G., A History of the Ptolemaic Empire, London, 2001.

- Lanciers, E., "Some Observations on the Events in Egypt in 145 B.C.," in L. Criscuolo et al. (eds.) Simblos scritti di storia antica, Bologna, 1995: 33-39.

- Whitehorne, J., Cleopatras, London, 1994.

External links

- Ptolemy, second son of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II entry in the online Ptolemaic Genealogy by Chris Bennett.

- Ptolemy Memphites, son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II entry in the online Ptolemaic Genealogy by Chris Bennett.

- Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith.