| Galba | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.png.webp) | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 8 June 68 – 15 January 69 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Nero | ||||||||

| Successor | Otho | ||||||||

| Born | 24 December 3 BC Near Terracina, Italy, Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Died | 15 January AD 69 (aged 71) Rome, Italy, Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Spouse | Aemilia Lepida | ||||||||

| Issue | Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi Licinianus (adopted) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Father | Gaius Sulpicius Galba | ||||||||

| Mother | Mummia Achaica Livia Ocellina (adoptive) | ||||||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year of the Four Emperors | ||

| Chronology | ||

| Succession | ||

|

||

Galba (/ˈɡælbə/, GAL-bə; born Servius Sulpicius Galba; 24 December 3 BC – 15 January AD 69) was Roman emperor, ruling from AD 68 to 69. He was the first emperor in the Year of the Four Emperors and assumed the throne following Emperor Nero's suicide.

Born into a wealthy family, Galba held at various times the positions of praetor, consul, and governor to the provinces of Gallia Aquitania, Germania Superior, and Africa during the first half of the first century AD. He retired from his positions during the latter part of Claudius' reign (with the advent of Agrippina the Younger), but Nero later granted him the governorship of Hispania. Taking advantage of the defeat of Vindex's rebellion and Nero's suicide, he became emperor with the support of the Praetorian Guard.

Galba's physical weakness and general apathy led to his being dominated by favorites. Unable to gain popularity with the people or maintain the support of the Praetorian Guard, Galba was murdered on the orders of Otho, who became emperor in his place.

Origins and family life

_(35867773310)_edited.jpg.webp)

Galba was not related to any of the emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, but he was a member of a distinguished noble family. The origin of the cognomen Galba is uncertain. Suetonius offers a number of possible explanations; the first member of the gens Sulpicia to bear the name might have gotten the name from the term galba, which the Romans used to describe the Gauls, or after an insect called galbae.[6] One of Galba's ancestors had been consul in 200 BC, and another of his ancestors was consul in 144 BC; the later emperor's father and brother, both named Gaius, would hold the office in 5 BC and AD 22 respectively.[7][8] Galba's grandfather was a historian and his son was a barrister whose first marriage was to Mummia Achaica, granddaughter of Quintus Lutatius Catulus and great-granddaughter of Lucius Mummius Achaicus;[7] Galba prided himself on his descent from his great-grandfather Catulus. According to Suetonius, he fabricated a genealogy of paternal descent from the god Jupiter and maternal descent from the legendary Pasiphaë, wife of Minos.[8] Reportedly, Galba was distantly related to Livia[9] to whom he had much respect and in turn by whom he was advanced in his career; in her will she left him fifty million sesterces; Emperor Tiberius however cheated Galba by reducing the amount to five hundred thousand sesterces and never even paid Galba the reduced amount.[10]

Servius Sulpicius Galba was born near Terracina on 24 December 3 BC.[11] His elder brother Gaius fled from Rome and committed suicide because the emperor Tiberius would not allow him to control a Roman province. Livia Ocellina became the second wife of Galba's father, whom she may have married because of his wealth; he was short and hunchbacked. Ocellina adopted Galba, and he took the name "Lucius Livius Ocella Sulpicius Galba", although he probably kept his original name in unofficial context, as evidenced by the fact that he reverted back to it upon his accession as emperor.[12] Galba preferred males over females in terms of sexual attraction;[7] according to Suetonius, he "preferred full-grown, strong men".[13] Nevertheless, he married a woman named Aemilia Lepida and had two sons.[14] Aemilia and their sons died during the early years of the reign of Claudius (r. 41–54). Galba would remain a widower for the rest of his life.[15]

Public service

Galba became praetor in about 30,[14] then governor of Aquitania for about a year,[16] then consul in 33.[14] In 39 the emperor Caligula learned of a plot against himself in which Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, the general of the legions of Germania Superior, was an important figure; Caligula installed Galba in the post held by Gaetulicus.[17] According to one report Galba ran alongside Caligula's chariot for twenty miles.[18] As commander of the legions of Germania Superior, Galba gained a reputation as a disciplinarian.[16] Suetonius writes that Galba was advised to take the throne following the assassination of Caligula in 41, but loyally served Caligula's uncle and successor Claudius (r. 41–54); this story may simply be fictional. Galba was appointed as governor of Africa in 44 or 45. He retired at an uncertain time during the reign of Claudius, possibly in 49. He was recalled in 59 or 60 by the emperor Nero (r. 54–68) to govern Hispania.[17]

A rebellion against Nero was orchestrated by Gaius Julius Vindex in Gaul on the anniversary of the death of Nero's mother, Agrippina the Younger, in 68. Shortly afterwards Galba, in rebellion against Nero, rejected the title "General of Caesar" in favor of "General of The Senate and People of Rome". He was supported by the imperial official Tigellinus. At midnight on 8 June, another imperial official, Nymphidius Sabinus, falsely announced to the Praetorian Guard that Nero had fled to Egypt, and the Senate proclaimed Galba emperor. Nero then committed assisted suicide with help from his secretary.[19][25]

Emperor (June 68)

Rule

Upon becoming emperor, Galba was faced by the rebellion of Nymphidius Sabinus, who had his own aspirations for the imperial throne. However, Sabinus was killed by the Praetorians before he could take the throne. While Galba was arriving to Rome with the Lusitanian governor Marcus Salvius Otho, his army was attacked by a legion that had been organized by Nero; a number of Galba's troops were killed in the fighting.[26] Galba, who suffered from chronic gout by the time he came to the throne,[7] was advised by a corrupt group which included the general Titus Vinius, commander of one of the legions in Hispania; the praetorian prefect Cornelius Laco, and Icelus, a freedman of Galba. Galba seized the property of Roman citizens, disbanded the Germanian legions, and did not pay the Praetorians and the soldiers who fought against Vindex. These actions caused him to become unpopular.[26]

Suetonius wrote the following descriptions of Galba's character and physical description:

Even before he reached middle life, he persisted in keeping up an old and forgotten custom of his country, which survived only in his own household, of having his freedmen and slaves appear before him twice a day in a body, greeting him in the morning and bidding him farewell at evening, one by one.

His double reputation for cruelty and avarice had gone before him; men said that he had punished the cities of the Spanish and Gallic provinces which had hesitated about taking sides with him by heavier taxes and some even by the razing of their walls, putting to death the governors and imperial deputies along with their wives and children. Further, that he had melted down a golden crown of fifteen pounds weight, which the people of Tarraco had taken from their ancient temple of Jupiter and presented to him, with orders that the three ounces which were found lacking be exacted from them. This reputation was confirmed and even augmented immediately on his arrival in the city. For having compelled some marines whom Nero had made regular soldiers to return to their former position as rowers, upon their refusing and obstinately demanding an eagle and standards, he not only dispersed them by a cavalry charge, but even decimated them. He also disbanded a cohort of Germans, whom the previous Caesars had made their body-guard and had found absolutely faithful in many emergencies, and sent them back to their native country without any rewards, alleging that they were more favourably inclined towards Gnaeus Dolabella, near whose gardens they had their camp. The following tales too were told in mockery of him, whether truly or falsely: that when an unusually elegant dinner was set before him, he groaned aloud; that when his duly appointed steward presented his expense account, he handed him a dish of beans in return for his industry and carefulness; and that when the flute player Canus greatly pleased him, he presented him with five denarii, which he took from his own purse with his own hand.

Accordingly, his coming was not so welcome as it might have been, and this was apparent at the first performance in the theatre; for when the actors of an Atellan farce began the familiar lines "Here comes Onesimus from his farm" all the spectators at once finished the song in chorus and repeated it several times with appropriate gestures, beginning with that verse. Thus his popularity and prestige were greater when he won, than while he ruled the empire, though he gave many proofs of being an excellent prince; but he was by no means so much loved for those qualities as he was hated for his acts of the opposite character.

— Suetonius

Particularly bad was his becoming under the influence of Vinius, Laco and Icelus:[27]

...To these brigands, each with his different vice, he so entrusted and handed himself over as their tool, that his conduct was far from consistent; for now he was more exacting and niggardly, and now more extravagant and reckless than became a prince chosen by the people and of his time of life. He condemned to death distinguished men of both orders on trivial suspicions without a trial. He rarely granted Roman citizenship, and the privileges of threefold paternity to hardly one or two, and even to those only for a fixed and limited time. When the jurors petitioned that a sixth division be added to their number, he not only refused, but even deprived them of the privilege granted by Claudius, of not being summoned for court duty in winter and at the beginning of the year.

— Suetonius

In regard to his appointment of Vitellius to Germania Inferior:[28]

Galba surprised everyone by sending him to Lower Germany. Some think that it was due to Titus Vinius, who had great influence at the time, and whose friendship Vitellius had long since won through their common support of the Blues. But since Galba openly declared that no men were less to be feared than those who thought of nothing but eating, and that Vitellius's bottomless gullet might be filled from the resources of the province, it is clear to anyone that he was chosen rather through contempt than favour.

— Suetonius

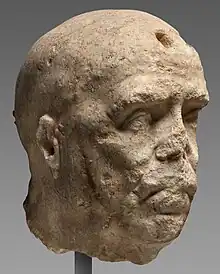

Further on his physical appearance and end of reign:[29]

He was of average height, very bald, with blue eyes and a hooked nose. His hands and feet were so distorted by gout that he could not endure a shoe for long, unroll a book, or even hold one. The flesh on his right side too had grown out and hung down to such an extent, that it could with difficulty be held in place by a bandage. It is said that he was a heavy eater and in winter time was in the habit of taking food even before daylight, while at dinner he helped himself so lavishly that he would have the leavings which remained in a heap before him passed along and distributed among the attendants who waited on him..... He met his end in the seventy-third year of his age and the seventh month of his reign. The senate, as soon as it was allowed to do so, voted him a statue standing upon a column adorned with the beaks of ships, in the part of the Forum where he was slain; but Vespasian annulled this decree, believing that Galba had sent assassins from Spain to Judaea, to take his life.

— Suetonius

Tacitus comments on the character of Galba: "He seemed too great to be a subject so long as he was subject, and all would have agreed that he was equal to the imperial office if he had never held it."[30]

Suetonius went on to say that Galba was visited by the Roman Goddess Fortuna in his dreams twice; on the latter occasion she "withdrew her support". This happened right before his later downfall.[31]

Mutiny on the frontier and assassination

On 1 January 69, the day Galba and Vinius took the office of consul,[37] the fourth and twenty-second legions of Germania Superior refused to swear loyalty to Galba. They toppled his statues, demanding that a new emperor be chosen. On the following day, the soldiers of Germania Inferior also refused to swear their loyalty and proclaimed the governor of the province, Aulus Vitellius, as emperor. Galba tried to ensure his authority as emperor was recognised by adopting the nobleman Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus as his successor. Nevertheless, Galba was killed by the Praetorians on 15 January.[38][39] Otho was angry that he had been passed over for adoption, and organised a conspiracy with a small number of Praetorian Guards to murder the aged emperor and elevate himself. The soldiery in the capital, composed not just of Praetorians but of Galba's legion from Hispania and several detachments of men from the Roman fleet, Illyria, Britannia, and Germania, were angered at not having received a donative.[40] They also resented Galba's purges of their officers and fellow soldiers (this was especially true of the men from the fleet). Many in the Praetorian Guard were shaken by the recent murder of their Prefect Nymphidius Sabinus – some of the waverers were convinced to come over to Otho's side out of fear Galba might yet take revenge on them for their connection to Sabinus.[41]

According to Suetonius, Galba put on a linen corset although remarking it was little protection against so many swords; when a soldier claimed to have killed Otho, Galba snapped "On what authority?" He was lured out to the scene of his assassination in the Forum by a false report of the conspirators. Galba either tried to buy his life with a promise of the withheld bounty or asked that he be beheaded. The only help for him was a centurion in the Praetorian Guard named Sempronius Densus, who was killed trying to defend Galba with a pugio; one hundred and twenty persons later petitioned Otho that they had killed Galba; they would be executed by Vitellius.[42] A company of Germanic soldiers to whom he had once done a kindness rushed to help him; however they took a wrong turn and arrived too late. He was killed near the Lacus Curtius.[43] Vinius tried to run away, calling out that Otho had not ordered him killed, but was run through with a spear.[44] Laco was banished to an island where he was later murdered by soldiers of Otho. Icelus was publicly executed.[45] Piso was also killed; his head along with Galba's and Vinius' were placed on poles and Otho was then acclaimed as emperor.[39] Galba's head was brought by a soldier to Otho's camp where camp boys mocked it on a lance – Galba had angered them previously by remarking his vigor was still unimpeded. Vinius' head was sold to his daughter for 2500 drachmas; Piso's head was given to his wife.[46] Galba's head was bought for 100 gold pieces by a freeman who threw it at Sessorium where his master Patrobius Neronianus had been killed by Galba. The body of Galba was taken up by Priscus Helvidius with the permission of Otho; at night [46] Galba's steward Argivus took both the head and body to a tomb in Galba's private gardens on the Aurelian Way.[47]

References

Citations

- ↑ Fasti Ostienses; AE 1978, 295

- ↑ Sometimes "Servius Galba Imperator Caesar Augustus" or "Imperator Servius Sulpicius Galba Caesar Augustus". Hammond, Mason (1957). "Imperial Elements in the Formula of the Roman Emperors during the First Two and a Half Centuries of the Empire". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 25: 19–64 (24). doi:10.2307/4238646. JSTOR 4238646.

- ↑ "Gammal man, kallad Galba. Porträtthuvud från sen republikansk tid" [Old man, called Galba. Portrait head from the late republican era]. Nationalmuseum.se.

- ↑ Slive, Seymour (2019). Rembrandt Drawings. Getty Publications. pp. 160–164. ISBN 978-1-60606-636-2.

- ↑ Benesch, Otto (1955). The Drawings of Rembrandt. Phaidon Press.

The shape of the cranium of the Stockholm bust is so different from that of the drawing — bulging and protruding in the Stockholm bust, receding and flattened in the Rembrandt drawing — that the identification, in spite of the similarity of the features, may be questioned.

- ↑ Suetonius, 3.1.

- 1 2 3 4 Greenhalgh 1975, p. 11.

- 1 2 Morgan 2006, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Suetonius Life of Galba Chapter 23

- ↑ Suetonius Life of Galba Chapter 3

- ↑ Suetonius, 4.1., in the year of the consulship of Cornelius Lentulus and Messalla Messallinus. This information is later contradicted by the statement that he died "in the seventy-third year of his age", which would place his birth in 5 BC. This number is repeated by Tacitus in Histories 1.49..

- ↑ Morgan 2006, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Suetonius, 22.

- 1 2 3 Lendering 2006.

- ↑ Morgan 2006, p. 32.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh 1975, p. 15.

- 1 2 Morgan 2006, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Suentonius "Life of Galba" Chapter 6

- ↑ Greenhalgh 1975, pp. 7–11.

- ↑ To Autolycus III.27. "7 months 6 days".

- ↑ Wilson, William (trans.) (1867). "The Writings of Clement of Alexandria". p. 444. "Seven months and six days".

- ↑ The Jewish War IV.491. "Reigned seven months and as many days".

- ↑ Epitome de Caesaribus 6. "Ruled seven months and an equal number of days".

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Historia Romana LXIII, 26.

- ↑ Theophilus of Antioch and Clement of Alexandria (2nd century) give 9 June as the beginning of Galba's rule.[20][21] Josephus (1st century) and Aurelius Victor (4th century) give 8 June.[22][23] Cassius Dio states that Galba was proclaimed emperor by the Senate the night before Nero's suicide, i.e. 8 June.[24]

- 1 2 Donahue 1999.

- ↑ Suetonius "Life of Galba" Chapters 4; 12–14

- ↑ Suetonius "Life of Vitellius" Chapter 7

- ↑ Suetonius "Life of Galba" Chapters 21–23

- ↑ Histories 1.49

- ↑ Hekster, Olivier (March 2009). "Reversed Epiphanies: Roman Emperors Deserted by Gods". Mnemosyne. 63 (4): 601–615. doi:10.1163/156852510X456228. hdl:2066/61695. JSTOR 25801887. S2CID 162876998.

- ↑ "Over Life-Size Relief Head of Emperor Galba?". J. Paul Getty Museum Collection.

- 1 2 Frel, Jiří (1994). Studia Varia. L'Erma di Bretschneider. p. 124. ISBN 978-88-7062-814-2.

- 1 2 Varner, Eric (2004). Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture. Brill. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-90-474-0470-5.

- ↑ "House of Galba (Casa di Galba) (Herculaneum)". ermakvagus.com.

- ↑ The other one is a damaged silver bust in the so-called "House of Galba", in Herculaneum.[33][34][35]

- ↑ Wellesley 1989, p. 1.

- ↑ Plutarch 24.1: "the eighteenth before the Calends of February", also in Tacitus, Histories 27-49.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh 1975, pp. 30, 37, 45, 47–54.

- ↑ Tacitus, Histories; Book I. 5–8

- ↑ Tacitus, Histories; Book I. 25–28

- ↑ Plutarch "Life of Galba" Chapters 26–27

- ↑ Suetonius "Life of Galba" Chapters 19–20

- ↑ Cornelius Tacitus (1770). The Works of Tacitus. J. and F. Rivington. p. 12.

- ↑ Tacitus p. 46

- 1 2 Plutarch "Life of Galba" Chapter 28

- ↑ Suetonius, Galba, 20, 21.

Bibliography

Ancient sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, fragments of Book 63 (English translation by Earnest Cary on LacusCurtius).

- Plutarch, Life of Galba (English translation by A.H. Clough on Wikisource).

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Galba (English translation by John Carew Rolfe on Wikisource).

Modern sources

- Donahue, John (7 August 1999). "Galba". De Imperatoribus Romanis. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Galba". The Royal Titulary of Ancient Egypt. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Greenhalgh, P. A. L. (1975). The Year of the Four Emperors. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 9780297768760.

- Morgan, Gwyn (2006). 69 A.D.: The Year of the Four Emperors. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195124682.

- Lendering, Jona (2006). "Galba". Livius. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Tranquillus, C. Suetonius (2018) [121]. De Vita Caesarum [The Lives of the Twelve Caesars] (in Latin). Translated by Rolfe, J. C. DOVER PUBNS. ISBN 9780486822198.

- Wellesley, Kenneth (1989). The Long Year A.D. 69. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 9781853990496.

External links

Media related to Galba at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Galba at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)

_(reverse).jpg.webp)