Third Dynasty of Egypt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2686 BCE–c. 2613 BCE | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Memphis | ||||||||

| Common languages | Egyptian language | ||||||||

| Religion | ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Established | c. 2686 BCE | ||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 2613 BCE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt |

|---|

|

All years are BC |

|

See also: List of pharaohs by period and dynasty Periodization of ancient Egypt |

The Third Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty III) is the first dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Other dynasties of the Old Kingdom include the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth. The capital during the period of the Old Kingdom was at Memphis.

Overview

After the turbulent last years of the Second Dynasty, which might have included civil war, Egypt came under the rule of Djoser, marking the beginning of the Third Dynasty.[1] Both the Turin King List and the Abydos King List record five kings,[2] while the Saqqara Tablet only records four, and Manetho records nine,[3] many of whom did not exist or are simply the same king under multiple names.

- The Turin King List gives Nebka, Djoser, Djoserti, Hudjefa I, and Huni.

- The Abydos King List gives Nebka, Djoser, Teti, Sedjes, and Neferkare.

- The Saqqara Tablet gives Djoser, Djoserteti, Nebkare, and Huni.

- Manetho gives Necheróphes (Nebka), Tosorthrós (Djoser), Týreis (Djoserti/Sekhemkhet), Mesôchris (Sanakht, probably the same person as Nebka), Sôÿphis (also Djoser), Tósertasis (also Djoserti/Sekhemkhet), Achês (Nebtawy Nebkare; unlikely Khaba, perhaps nonexistent), Sêphuris (Qahedjet), and Kerpherês (Huni).

The archaeological evidence shows that Khasekhemwy, the last ruler of the Second Dynasty, was succeeded by Djoser, who at the time was only attested by his presumed Horus name Netjerikhet. Djoser's successor was Sekhemkhet, who had the Nebty name Djeserty. The last king of the dynasty is Huni, who may be the same person as Qahedjet or, less likely, Khaba. There are three remaining Horus names of known 3rd dynasty kings: Sanakht, Khaba, and perhaps Qahedjet. One of these three, by far most likely Sanakht, went by the nebty name Nebka.[2]

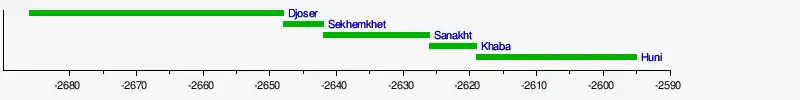

Dating the Third Dynasty is similarly challenging. Shaw gives the dates as being approximately from 2686 to 2613 BCE.[4] The Turin King List suggests a total of 75 years for the third dynasty. Baines and Malek have placed the third dynasty as spanning the years 2650–2575 BCE,[2] while Dodson and Hilton date the dynasty to 2584–2520 BCE. It is not uncommon for these estimates to differ by more than a century.[1]

Some scholars have proposed a southern origin for the Third Dynasty. Egyptologist, Flinders Petrie, believed the dynasty originated from Sudan based on the iconographic evidence whereas S.O.Y. Keita, a biological anthropologist, differed in his view and argued an origin in southern Egypt was “equally likely”.[5] He cited a previous X-ray and anthropological study which suggested that the Third Dynasty nobles had “Nubian affinities”. The author also interpreted the portrait of Djoser as having little resemblance to “portraits of late dynastic Greek/Roman conquerors” and cited an iconographic review conducted by anthropologist, John Drake, as supporting evidence.[6] In a separate article, Keita noted that the archaeological remains of the southern elites and their descendants which he discussed in reference to the Second Dynastic rulers and Djoser were eventually buried in the north and not at Abydos, Egypt.[7]

Rulers

The pharaohs of the Third Dynasty ruled for approximately seventy-five years. Due to recent archaeological findings in Abydos revealing that Djoser was the one who buried Khasekhemwy, the last king of the Second Dynasty, it is now widely believed that Djoser is the founder of the Third Dynasty, as the direct successor of Khasekhemwy and the one responsible for finishing his tomb.[8] These findings contradict earlier writings, like Wilkinson 1999, which proposed that Nebka/Sanakht was the founder of the dynasty. However, the two were not very far apart temporally; they may have been brothers, along with Sekhemkhet,[9][10] as the sons of Khasekhemwy and his favoured consort Nimaathap.

| Horus-name | Personal Name | Regnal years | Burial | Consort(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netjerikhet | Djoser |  | 19 or 28 | Saqqara: Pyramid of Djoser | Hetephernebti |

| Sekhemkhet | Djoserty |  | 6–7 | Saqqara: Buried Pyramid | Djeseretnebti |

| Sanakht | Nebka |  | 6–28 years, depending on identification; most likely six, 18, or 19 years | Possibly mastaba K2 at Beit Khallaf | |

| Khaba | Teti |  | 6 ? 24, if identical to Huni | Zawyet el'Aryan: Layer Pyramid | |

| Uncertain, Qahedjet ? | Huni |  | 24 | Meidum ? | Djefatnebti Meresankh I |

While Manetho names Necherophes, and the Turin King List names Nebka (a.k.a. Sanakht), as the first pharaoh of the Third Dynasty,[2] many contemporary Egyptologists believe Djoser was the first king of this dynasty, pointing out the order in which some predecessors of Khufu are mentioned in the Papyrus Westcar suggests that Nebka should be placed between Djoser and Huni, and not before Djoser. More importantly, seals naming Djoser were found at the entrance to Khasekhemwy's tomb at Abydos, which demonstrates that it was Djoser, rather than Sanakht, who buried and succeeded this king.[2] The Turin King List scribe wrote Djoser's name in red ink, which indicates the Ancient Egyptians' recognition of this king's historical importance in their culture. In any case, Djoser is the best known king of this dynasty, for commissioning his vizier Imhotep to build the earliest surviving pyramids, the Step Pyramid.

Nebka's identification with Sanakht is uncertain; though many Egyptologists continue to support the theory that the two kings were one and the same man, opposition exists because this opinion rests on a single fragmentary clay seal discovered in 1903 by John Garstang. Though damaged, the seal displays the serekh of Sanakht, together with a cartouche containing a form of the sign for "ka," with just enough room for the sign for "Neb." Nebka's reign length is given as eighteen years by both Manetho and the Turin Canon, though it is important to note that these sources write over 2,300 and 1,400 years after his lifetime, so their accuracy is uncertain. In contrast to Djoser, both Sanakht and Nebka are attested in considerably few relics for a ruler of nearly two decades; the Turin Canon gives a reign of only six years to an unnamed immediate predecessor of Huni. Toby Wilkinson suggests that this number fits Sanakht (whom he identifies concretely with Nebka), given the sparsity of archaeological evidence for him, but it could also be the reign length of Khaba or even Qahedjet, kings whose identities are uncertain. (Wilkinson places Nebka as the penultimate king of the Third Dynasty, before Huni, but this is by no means definitively known or even overwhelmingly supported among Egyptologists.)

Some authorities believe that Imhotep lived into the reign of the Pharaoh Huni. Little is known for certain of Sekhemkhet, but his reign is considered to have been only six or seven years, according to the Turin Canon and Palermo Stone, respectively. Attempts to equate Sekhemkhet with Tosertasis, a king assigned nineteen years by Manetho, find almost no support given the unfinished state of his tomb, the Buried Pyramid. It is believed that Khaba possibly built the Layer Pyramid at Zawyet el'Aryan; the pyramid is far smaller than it was intended to be, but it is not known whether this is due to natural erosion or because it, like Sekhemkhet's own tomb, was never completed to begin with. In any case, the duration of Khaba's reign is uncertain; a few Egyptologists believe Khaba was identical to Huni, but if Khaba is the same person as the Ramesside names Hudjeta II and Sednes, he could have reigned for six years.

Third Dynasty timeline

References

- 1 2 Dodson, Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, 2004

- 1 2 3 4 5 Toby A.H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge, 2001

- ↑ Aidan Dodson: The Layer Pyramid of Zawiyet el-Aryan: Its Layout and Context. In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt (JARCE), No. 37 (2000). American Research Center (Hg.), Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake/Bristol 2000, ISSN 0065-9991, pp. 81–90.

- ↑ Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 480. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ↑ Keita, S. O. Y. (March 1992). "Further studies of crania from ancient Northern Africa: An analysis of crania from First Dynasty Egyptian tombs, using multiple discriminant functions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 87 (3): 245–254. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330870302. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 1562056.

- ↑ Keita, S. O. Y. (1993). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa. 20: 129–154. doi:10.2307/3171969. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3171969. S2CID 162330365.

- ↑ Keita, S. O. Y. (March 1992). "Further studies of crania from ancient Northern Africa: An analysis of crania from First Dynasty Egyptian tombs, using multiple discriminant functions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 87 (3): 245–254. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330870302. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 1562056.

- ↑ Bard, Kathryn (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 140–145. ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2.

- ↑ Toby A. H. Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, London 2001, ISBN 0415260116, pp. 80–82, 94–97.

- ↑ Silke Roth: Die Königsmütter des Alten Ägypten von der Frühzeit bis zum Ende der 12. Dynastie (= Ägypten und Altes Testament, vol. 46). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04368-7, pp. 59–61, 65–67.