Modernism is a philosophical, religious, and art movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, and social organization which reflected the newly emerging industrial world, including features such as urbanization, architecture, new technologies, and war. Artists attempted to depart from traditional forms of art, which they considered outdated or obsolete. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 injunction to "Make it New" was the touchstone of the movement's approach.

Modernist innovations included abstract art, the stream of consciousness novel, montage cinema, atonal and twelve-tone music, divisionist painting and modern architecture. Modernism explicitly rejected the ideology of realism[lower-alpha 1][2][3] and made use of the works of the past by the employment of reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody.[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3][4] Modernism also rejected the certainty of Enlightenment thinking, and many modernists also rejected religious belief.[5][lower-alpha 4] A notable characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness concerning artistic and social traditions, which often led to experimentation with form, along with the use of techniques that drew attention to the processes and materials used in creating works of art.[7]

While some scholars see modernism continuing into the 21st century, others see it evolving into late modernism or high modernism.[8] Postmodernism is a departure from modernism and rejects its basic assumptions.[9][10][11]

Definition

Some commentators define modernism as a mode of thinking—one or more philosophically defined characteristics, like self-consciousness or self-reference, that run across all the novelties in the arts and the disciplines.[12] More common, especially in the West, are those who see it as a socially progressive trend of thought that affirms the power of human beings to create, improve, and reshape their environment with the aid of practical experimentation, scientific knowledge, or technology.[lower-alpha 5] From this perspective, modernism encouraged the re-examination of every aspect of existence, from commerce to philosophy, with the goal of finding that which was holding back progress, and replacing it with new ways of reaching the same end.

According to Roger Griffin, modernism can be defined as a broad cultural, social, or political initiative, sustained by the ethos of "the temporality of the new". Modernism sought to restore, Griffin writes, a "sense of sublime order and purpose to the contemporary world, thereby counteracting the (perceived) erosion of an overarching 'nomos', or 'sacred canopy', under the fragmenting and secularizing impact of modernity." Therefore, phenomena apparently unrelated to each other such as "Expressionism, Futurism, vitalism, Theosophy, psychoanalysis, nudism, eugenics, utopian town planning and architecture, modern dance, Bolshevism, organic nationalism – and even the cult of self-sacrifice that sustained the hecatomb of the First World War – disclose a common cause and psychological matrix in the fight against (perceived) decadence." All of them embody bids to access a "supra-personal experience of reality", in which individuals believed they could transcend their own mortality, and eventually that they had ceased to be victims of history to become instead its creators.[14]

Modernism, Romanticism, Philosophy and Symbol

Literary modernism is often summed up in a line from W. B. Yeats: "Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold" (in 'The Second Coming').[15] Modernists often search for a metaphysical 'centre' but experience its collapse.[16] (Postmodernism, by way of contrast, celebrate that collapse, exposing the failure of metaphysics, for instance in Jacques Derrida's deconstruction of metaphysical claims.)[17]

Philosophically, the collapse of metaphysics can be traced back to the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–1776), who argued that we never actually perceive one event causing another. We only experience the 'constant conjunction' of events, and do not perceive a metaphysical 'cause'. Similarly, Hume argues (without using the actual terms) that we never know the self as object, only the self as subject, and we are thus blind to our true natures.[18] More generally, if we only 'know' through sensory experience (seeing, touching, etc.), then we cannot 'know' or make metaphysical claims.

Modernism is thus often driven emotionally by the desire for metaphysical truths, while understanding their impossibility. Modernist novels, for instance, feature characters like Marlow in Heart of Darkness or Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby who believe that they have encountered some great truth about nature or character, truths that the novels themselves treat ironically, offering more mundane explanations.[19] Similarly, many poems of Wallace Stevens struggle with the sense of nature's significance, falling under two headings: poems in which the speaker denies that nature has meaning, only for nature to loom up by the end of the poem; and poems in which the speaker claims nature has meaning, only for that meaning to collapse by the end of the poem.

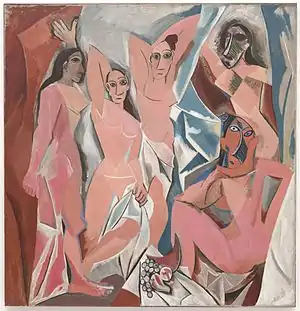

Modernism often rejects nineteenth century realism, if the latter is understood as focusing on the embodiment of meaning within a naturalistic representation. At the same time, some modernists aim at a more 'real' realism, one that is decentred. Picasso's proto-cubist painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon of 1907 (see picture above) does not present its subjects from a single point of view (that of a single viewer), but instead presents a flat, two-dimensional picture plane. 'The Poet' of 1911 is similarly decentred, presenting the body from every point of view. As the Peggy Guggenheim Collections website puts it, 'Picasso presents multiple views of each object, as if he had moved around it, and synthesizes them into a single compound image'.[20]

Modernism, with its sense that 'things fall apart,' can be seen as the apotheosis of romanticism, if romanticism is the (often frustrated) quest for metaphysical truths about character, nature, God and meaning in the world.[21] Modernism often yearns for a romantic or metaphysical centre, but finds only its collapse.

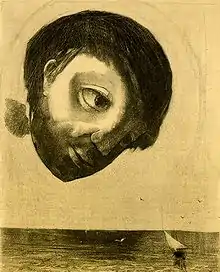

This distinction between modernism and romanticism extends to their respective treatments of 'symbol'. The romantics at times see an essential relation (the 'ground') between the symbol (the 'vehicle', in I.A. Richards's terms)[22] and its 'tenor' (its meaning)—for example in Coleridge's description of nature as 'that eternal language which thy God / Utters'.[23] But while nature and its symbols may be God's language, for some romantic theorists it remains inscrutable. As Goethe (not quite a romantic) said, 'the idea [or meaning] remains eternally and infinitely active and inaccessible in the image'.[24] This was extended in modernist theory which, drawing on its Symbolist precursors, often emphasises the inscrutability and failure of symbol and metaphor—for example in Stevens who seeks and fails to find meaning in nature, even if he at times seems to sense such a meaning. As such, symbolists and modernists at times adopt a mystical approach to suggest a non-rational sense of meaning.[25]

For these reasons, modernist metaphors are often unnatural, as for instance in T.S. Eliot's description of an evening 'spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a table'.[26] Similarly, in many later modernist poets nature is unnaturalised and at times mechanised, as for example in Stephen Oliver's image of the moon busily 'hoisting' itself into consciousness.[27]

Early history

Origins

According to a critic, modernism developed out of Romanticism's revolt against the effects of the Industrial Revolution and bourgeois values: "The ground motive of modernism, Graff asserts, was criticism of the nineteenth-century bourgeois social order and its world view [...] the modernists, carrying the torch of romanticism."[lower-alpha 1][2][3] While J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851), one of the greatest landscape painters of the 19th century, was a member of the Romantic movement, as "a pioneer in the study of light, colour, and atmosphere", he "anticipated the French Impressionists" and therefore modernism "in breaking down conventional formulas of representation; [though] unlike them, he believed that his works should always express significant historical, mythological, literary, or other narrative themes."[29]

The dominant trends of industrial Victorian England were opposed, from about 1850, by the English poets and painters that constituted the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, because of their "opposition to technical skill without inspiration."[30]: 815 They were influenced by the writings of the art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), who had strong feelings about the role of art in helping to improve the lives of the urban working classes, in the rapidly expanding industrial cities of Britain.[30]: 816 Art critic Clement Greenberg describes the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as proto-Modernists: "There the proto-Modernists were, of all people, the pre-Raphaelites (and even before them, as proto-proto-Modernists, the German Nazarenes). The Pre-Raphaelites actually foreshadowed Manet (1832–1883), with whom Modernist painting most definitely begins. They acted on a dissatisfaction with painting as practiced in their time, holding that its realism wasn't truthful enough."[31] Rationalism has also had opponents in the philosophers Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855)[32] and later Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), both of whom had significant influence on existentialism and nihilism.[33]: 120

However, the Industrial Revolution continued. Influential innovations included steam-powered industrialization, and especially the development of railways, starting in Britain in the 1830s,[34] and the subsequent advancements in physics, engineering, and architecture associated with this. A major 19th-century engineering achievement was The Crystal Palace, the huge cast-iron and plate glass exhibition hall built for the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Glass and iron were used in a similar monumental style in the construction of major railway terminals in London, such as Paddington Station (1854)[35] and King's Cross station (1852).[36] These technological advances led to the building of later structures like the Brooklyn Bridge (1883) and the Eiffel Tower (1889). The latter broke all previous limitations on how tall man-made objects could be. These engineering marvels radically altered the 19th-century urban environment and the daily lives of people. The human experience of time itself was altered, with the development of the electric telegraph from 1837,[37] and the adoption of standard time by British railway companies from 1845, and in the rest of the world over the next fifty years.[38]

Despite continuing technological advances, the idea that history and civilization were inherently progressive, and that progress was always good, came under increasing attack in the nineteenth century. Arguments arose that the values of the artist and those of society were not merely different, but that Society was antithetical to Progress, and could not move forward in its present form. Early in the century, the philosopher Schopenhauer (1788–1860) (The World as Will and Representation, 1819) had called into question the previous optimism, and his ideas had an important influence on later thinkers, including Nietzsche.[32] Two of the most significant thinkers of the mid nineteenth century were biologist Charles Darwin (1809–1882), author of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859), and political scientist Karl Marx (1818–1883), author of Das Kapital (1867). Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection undermined religious certainty and the idea of human uniqueness. In particular, the notion that human beings were driven by the same impulses as "lower animals" proved to be difficult to reconcile with the idea of an ennobling spirituality.[39] Karl Marx argued that there were fundamental contradictions within the capitalist system, and that the workers were anything but free.[40]

The beginnings in the late nineteenth century

Historians, and writers in different disciplines, have suggested various dates as starting points for modernism. Historian William Everdell, for example, has argued that modernism began in the 1870s, when metaphorical (or ontological) continuity began to yield to the discrete with mathematician Richard Dedekind's (1831–1916) Dedekind cut, and Ludwig Boltzmann's (1844–1906) statistical thermodynamics.[12] Everdell also thinks modernism in painting began in 1885–1886 with Seurat's Divisionism, the "dots" used to paint A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. On the other hand, visual art critic Clement Greenberg called Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) "the first real Modernist",[41] though he also wrote, "What can be safely called Modernism emerged in the middle of the last century—and rather locally, in France, with Baudelaire in literature and Manet in painting, and perhaps with Flaubert, too, in prose fiction. (It was a while later, and not so locally, that Modernism appeared in music and architecture)."[31] The poet Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), and Flaubert's novel Madame Bovary were both published in 1857. Baudelaire's essay "The Painter of Modern Life" (1863) inspired young artists to break away from tradition and innovate new ways of portraying their world in art.

In the arts and letters, two important approaches developed separately in France, beginning in the 1860s. The first was Impressionism, a school of painting that initially focused on work done, not in studios, but outdoors (en plein air). Impressionist paintings attempted to convey that human beings do not see objects, but instead see light itself. The school gathered adherents despite internal divisions among its leading practitioners, and became increasingly influential. Initially rejected from the most important commercial show of the time, the government-sponsored Paris Salon, the Impressionists organized yearly group exhibitions in commercial venues during the 1870s and 1880s, timing them to coincide with the official Salon. A significant event of 1863 was the Salon des Refusés, created by Emperor Napoleon III to display all of the paintings rejected by the Paris Salon. While most were in standard styles, but by inferior artists, the work of Manet attracted tremendous attention, and opened commercial doors to the movement. The second French school was Symbolism, which literary historians see beginning with Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), and including the later poets, Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891) Une Saison en Enfer (A Season in Hell, 1873), Paul Verlaine (1844–1896), Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898), and Paul Valéry (1871–1945). The symbolists "stressed the priority of suggestion and evocation over direct description and explicit analogy," and were especially interested in "the musical properties of language."[42]

Cabaret, which gave birth to so many of the arts of modernism, including the immediate precursors of film, may be said to have begun in France in 1881 with the opening of the Black Cat in Montmartre, the beginning of the ironic monologue, and the founding of the Society of Incoherent Arts.[43]

Influential in the early days of modernism were the theories of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). Freud's first major work was Studies on Hysteria (with Josef Breuer, 1895). Central to Freud's thinking is the idea "of the primacy of the unconscious mind in mental life," so that all subjective reality was based on the play of basic drives and instincts, through which the outside world was perceived. Freud's description of subjective states involved an unconscious mind full of primal impulses, and counterbalancing self-imposed restrictions derived from social values.[30]: 538

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) was another major precursor of modernism,[45] with a philosophy in which psychological drives, specifically the "will to power" (Wille zur Macht), was of central importance: "Nietzsche often identified life itself with 'will to power', that is, with an instinct for growth and durability."[46][47] Henri Bergson (1859–1941), on the other hand, emphasized the difference between scientific, clock time and the direct, subjective, human experience of time.[33]: 131 His work on time and consciousness "had a great influence on twentieth-century novelists," especially those modernists who used the stream of consciousness technique, such as Dorothy Richardson, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf (1882–1941).[48] Also important in Bergson's philosophy was the idea of élan vital, the life force, which "brings about the creative evolution of everything."[33]: 132 His philosophy also placed a high value on intuition, though without rejecting the importance of the intellect.[33]: 132

Important literary precursors of modernism were Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), who wrote the novels Crime and Punishment (1866) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880);[49] Walt Whitman (1819–1892), who published the poetry collection Leaves of Grass (1855–1891); and August Strindberg (1849–1912), especially his later plays, including the trilogy To Damascus 1898–1901, A Dream Play (1902) and The Ghost Sonata (1907). Henry James has also been suggested as a significant precursor, in a work as early as The Portrait of a Lady (1881).[50]

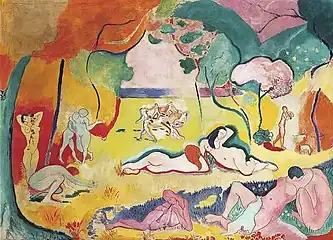

Out of the collision of ideals derived from Romanticism, and an attempt to find a way for knowledge to explain that which was as yet unknown, came the first wave of works in the first decade of the 20th century, which, while their authors considered them extensions of existing trends in art, broke the implicit contract with the general public that artists were the interpreters and representatives of bourgeois culture and ideas. These "Modernist" landmarks include the atonal ending of Arnold Schoenberg's Second String Quartet in 1908, the expressionist paintings of Wassily Kandinsky starting in 1903, and culminating with his first abstract painting and the founding of the Blue Rider group in Munich in 1911, and the rise of fauvism and the inventions of cubism from the studios of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and others, in the years between 1900 and 1910.

Main period

Early 20th century to 1930

.jpg.webp)

An important aspect of modernism is how it relates to tradition through its adoption of techniques like reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3]

T. S. Eliot made significant comments on the relation of the artist to tradition, including: "[W]e shall often find that not only the best, but the most individual parts of [a poet's] work, may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously."[53] However, the relationship of Modernism with tradition was complex, as literary scholar Peter Childs indicates: "There were paradoxical if not opposed trends towards revolutionary and reactionary positions, fear of the new and delight at the disappearance of the old, nihilism and fanatical enthusiasm, creativity and despair."[4]

An example of how Modernist art can be both revolutionary and yet be related to past tradition, is the music of the composer Arnold Schoenberg. On the one hand Schoenberg rejected traditional tonal harmony, the hierarchical system of organizing works of music that had guided music making for at least a century and a half. He believed he had discovered a wholly new way of organizing sound, based in the use of twelve-note rows. Yet while this was indeed wholly new, its origins can be traced back in the work of earlier composers, such as Franz Liszt,[54] Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss and Max Reger.[55][56] Schoenberg also wrote tonal music throughout his career.

In the world of art, in the first decade of the 20th century, young painters such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were causing a shock with their rejection of traditional perspective as the means of structuring paintings,[57][58] though the impressionist Monet had already been innovative in his use of perspective.[59] In 1907, as Picasso was painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Oskar Kokoschka was writing Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murderer, Hope of Women), the first Expressionist play (produced with scandal in 1909), and Arnold Schoenberg was composing his String Quartet No.2 in F sharp minor (1908), his first composition without a tonal centre.

A primary influence that led to Cubism was the representation of three-dimensional form in the late works of Paul Cézanne, which were displayed in a retrospective at the 1907 Salon d'Automne.[60] In Cubist artwork, objects are analyzed, broken up and reassembled in an abstracted form; instead of depicting objects from one viewpoint, the artist depicts the subject from a multitude of viewpoints to represent the subject in a greater context.[61] Cubism was brought to the attention of the general public for the first time in 1911 at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris (held 21 April – 13 June). Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger and Roger de La Fresnaye were shown together in Room 41, provoking a 'scandal' out of which Cubism emerged and spread throughout Paris and beyond. Also in 1911, Kandinsky painted Bild mit Kreis (Picture with a Circle), which he later called the first abstract painting.[62]: 167 In 1912, Metzinger and Gleizes wrote the first (and only) major Cubist manifesto, Du "Cubisme", published in time for the Salon de la Section d'Or, the largest Cubist exhibition to date. In 1912 Metzinger painted and exhibited his enchanting La Femme au Cheval (Woman with a Horse) and Danseuse au Café (Dancer in a Café). Albert Gleizes painted and exhibited his Les Baigneuses (The Bathers) and his monumental Le Dépiquage des Moissons (Harvest Threshing). This work, along with La Ville de Paris (City of Paris) by Robert Delaunay, was the largest and most ambitious Cubist painting undertaken during the pre-War Cubist period.[63]

In 1905, a group of four German artists, led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, formed Die Brücke (the Bridge) in the city of Dresden. This was arguably the founding organization for the German Expressionist movement, though they did not use the word itself. A few years later, in 1911, a like-minded group of young artists formed Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in Munich. The name came from Wassily Kandinsky's Der Blaue Reiter painting of 1903. Among their members were Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Paul Klee, and August Macke. However, the term "Expressionism" did not firmly establish itself until 1913.[62]: 274 Though initially mainly a German artistic movement,[lower-alpha 6] most predominant in painting, poetry and the theatre between 1910 and 1930, most precursors of the movement were not German. Furthermore, there have been expressionist writers of prose fiction, as well as non-German speaking expressionist writers, and, while the movement had declined in Germany with the rise of Adolf Hitler in the 1930s, there were subsequent expressionist works.

Expressionism is notoriously difficult to define, in part because it "overlapped with other major 'isms' of the modernist period: with Futurism, Vorticism, Cubism, Surrealism and Dada."[66] Richard Murphy also comments: "the search for an all-inclusive definition is problematic to the extent that the most challenging expressionists" such as the novelist Franz Kafka, poet Gottfried Benn, and novelist Alfred Döblin were simultaneously the most vociferous anti-expressionists.[67]: 43 What, however, can be said, is that it was a movement that developed in the early 20th century mainly in Germany in reaction to the dehumanizing effect of industrialization and the growth of cities, and that "one of the central means by which expressionism identifies itself as an avant-garde movement, and by which it marks its distance to traditions and the cultural institution as a whole is through its relationship to realism and the dominant conventions of representation."[67]: 43 More explicitly: that the expressionists rejected the ideology of realism.[67]: 43–48 [68] There was a concentrated Expressionist movement in early 20th century German theatre, of which Georg Kaiser and Ernst Toller were the most famous playwrights. Other notable Expressionist dramatists included Reinhard Sorge, Walter Hasenclever, Hans Henny Jahnn, and Arnolt Bronnen. They looked back to Swedish playwright August Strindberg and German actor and dramatist Frank Wedekind as precursors of their dramaturgical experiments. Oskar Kokoschka's Murderer, the Hope of Women was the first fully Expressionist work for the theatre, which opened on 4 July 1909 in Vienna.[69] The extreme simplification of characters to mythic types, choral effects, declamatory dialogue and heightened intensity would become characteristic of later Expressionist plays. The first full-length Expressionist play was The Son by Walter Hasenclever, which was published in 1914 and first performed in 1916.[70]

Futurism is yet another modernist movement.[71] In 1909, the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro published F. T. Marinetti's first manifesto. Soon afterwards a group of painters (Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, and Gino Severini) co-signed the Futurist Manifesto. Modeled on Marx and Engels' famous "Communist Manifesto" (1848), such manifestoes put forward ideas that were meant to provoke and to gather followers. However, arguments in favor of geometric or purely abstract painting were, at this time, largely confined to "little magazines" which had only tiny circulations. Modernist primitivism and pessimism were controversial, and the mainstream in the first decade of the 20th century was still inclined towards a faith in progress and liberal optimism.

Abstract artists, taking as their examples the impressionists, as well as Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and Edvard Munch (1863–1944), began with the assumption that color and shape, not the depiction of the natural world, formed the essential characteristics of art.[73] Western art had been, from the Renaissance up to the middle of the 19th century, underpinned by the logic of perspective and an attempt to reproduce an illusion of visible reality. The arts of cultures other than the European had become accessible and showed alternative ways of describing visual experience to the artist. By the end of the 19th century many artists felt a need to create a new kind of art which would encompass the fundamental changes taking place in technology, science and philosophy. The sources from which individual artists drew their theoretical arguments were diverse, and reflected the social and intellectual preoccupations in all areas of Western culture at that time.[74] Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich all believed in redefining art as the arrangement of pure color. The use of photography, which had rendered much of the representational function of visual art obsolete, strongly affected this aspect of modernism.[75]

Modernist architects and designers, such as Frank Lloyd Wright[76] and Le Corbusier,[77] believed that new technology rendered old styles of building obsolete. Le Corbusier thought that buildings should function as "machines for living in", analogous to cars, which he saw as machines for traveling in.[78] Just as cars had replaced the horse, so modernist design should reject the old styles and structures inherited from Ancient Greece or from the Middle Ages. Following this machine aesthetic, modernist designers typically rejected decorative motifs in design, preferring to emphasize the materials used and pure geometrical forms.[79] The skyscraper is the archetypal modernist building, and the Wainwright Building, a 10-story office building built 1890–91, in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, is among the first skyscrapers in the world.[80] Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Seagram Building in New York (1956–1958) is often regarded as the pinnacle of this modernist high-rise architecture.[81] Many aspects of modernist design still persist within the mainstream of contemporary architecture, though previous dogmatism has given way to a more playful use of decoration, historical quotation, and spatial drama.

In 1913—which was the year of philosopher Edmund Husserl's Ideas, physicist Niels Bohr's quantized atom, Ezra Pound's founding of imagism, the Armory Show in New York, and in Saint Petersburg the "first futurist opera", Mikhail Matyushin's Victory over the Sun—another Russian composer, Igor Stravinsky, composed The Rite of Spring, a ballet that depicts human sacrifice, and has a musical score full of dissonance and primitive rhythm. This caused uproar on its first performance in Paris. At this time though modernism was still "progressive", increasingly it saw traditional forms and traditional social arrangements as hindering progress, and was recasting the artist as a revolutionary, engaged in overthrowing rather than enlightening society. Also in 1913 a less violent event occurred in France with the publication of the first volume of Marcel Proust's important novel sequence À la recherche du temps perdu (1913–1927) (In Search of Lost Time). This is often presented as an early example of a writer using the stream-of-consciousness technique, but Robert Humphrey comments that Proust "is concerned only with the reminiscent aspect of consciousness" and that he "was deliberately recapturing the past for the purpose of communicating; hence he did not write a stream-of-consciousness novel."[82]

Stream of consciousness was an important modernist literary innovation, and it has been suggested that Arthur Schnitzler (1862–1931) was the first to make full use of it in his short story "Leutnant Gustl" ("None but the Brave") (1900).[83] Dorothy Richardson was the first English writer to use it, in the early volumes of her novel sequence Pilgrimage (1915–1967).[lower-alpha 7] The other modernist novelists that are associated with the use of this narrative technique include James Joyce in Ulysses (1922) and Italo Svevo in La coscienza di Zeno (1923).[85]

However, with the coming of the Great War of 1914–1918 and the Russian Revolution of 1917, the world was drastically changed and doubt cast on the beliefs and institutions of the past. The failure of the previous status quo seemed self-evident to a generation that had seen millions die fighting over scraps of earth: prior to 1914 it had been argued that no one would fight such a war, since the cost was too high. The birth of a machine age which had made major changes in the conditions of daily life in the 19th century now had radically changed the nature of warfare. The traumatic nature of recent experience altered basic assumptions, and realistic depiction of life in the arts seemed inadequate when faced with the fantastically surreal nature of trench warfare. The view that mankind was making steady moral progress now seemed ridiculous in the face of the senseless slaughter, described in works such as Erich Maria Remarque's novel All Quiet on the Western Front (1929). Therefore, modernism's view of reality, which had been a minority taste before the war, became more generally accepted in the 1920s.

In literature and visual art some modernists sought to defy expectations mainly in order to make their art more vivid, or to force the audience to take the trouble to question their own preconceptions. This aspect of modernism has often seemed a reaction to consumer culture, which developed in Europe and North America in the late 19th century. Whereas most manufacturers try to make products that will be marketable by appealing to preferences and prejudices, high modernists rejected such consumerist attitudes in order to undermine conventional thinking. The art critic Clement Greenberg expounded this theory of modernism in his essay Avant-Garde and Kitsch.[86] Greenberg labeled the products of consumer culture "kitsch", because their design aimed simply to have maximum appeal, with any difficult features removed. For Greenberg, modernism thus formed a reaction against the development of such examples of modern consumer culture as commercial popular music, Hollywood, and advertising. Greenberg associated this with the revolutionary rejection of capitalism.

Some modernists saw themselves as part of a revolutionary culture that included political revolution. In Russia after the 1917 Revolution there was indeed initially a burgeoning of avant-garde cultural activity, which included Russian Futurism. However others rejected conventional politics as well as artistic conventions, believing that a revolution of political consciousness had greater importance than a change in political structures. But many modernists saw themselves as apolitical. Others, such as T. S. Eliot, rejected mass popular culture from a conservative position. Some even argue that modernism in literature and art functioned to sustain an elite culture which excluded the majority of the population.[86]

Surrealism, which originated in the early 1920s, came to be regarded by the public as the most extreme form of modernism, or "the avant-garde of Modernism".[87] The word "surrealist" was coined by Guillaume Apollinaire and first appeared in the preface to his play Les Mamelles de Tirésias, which was written in 1903 and first performed in 1917. Major surrealists include Paul Éluard, Robert Desnos,[88] Max Ernst, Hans Arp, Antonin Artaud, Raymond Queneau, Joan Miró, and Marcel Duchamp.[89]

By 1930, Modernism had won a place in the establishment, including the political and artistic establishment, although by this time Modernism itself had changed.

Modernism continues: 1930–1945

Modernism continued to evolve during the 1930s. Between 1930 and 1932 composer Arnold Schoenberg worked on Moses und Aron, one of the first operas to make use of the twelve-tone technique,[90] Pablo Picasso painted in 1937 Guernica, his cubist condemnation of fascism, while in 1939 James Joyce pushed the boundaries of the modern novel further with Finnegans Wake. Also by 1930 Modernism began to influence mainstream culture, so that, for example, The New Yorker magazine began publishing work, influenced by Modernism, by young writers and humorists like Dorothy Parker,[91] Robert Benchley, E. B. White, S. J. Perelman, and James Thurber, amongst others.[92] Perelman is highly regarded for his humorous short stories that he published in magazines in the 1930s and 1940s, most often in The New Yorker, which are considered to be the first examples of surrealist humor in America.[93] Modern ideas in art also began to appear more frequently in commercials and logos, an early example of which, from 1916, is the famous London Underground logo designed by Edward Johnston.[94]

One of the most visible changes of this period was the adoption of new technologies into daily life of ordinary people in Western Europe and North America. Electricity, the telephone, the radio, the automobile—and the need to work with them, repair them and live with them—created social change. The kind of disruptive moment that only a few knew in the 1880s became a common occurrence. For example, the speed of communication reserved for the stock brokers of 1890 became part of family life, at least in middle class North America. Associated with urbanization and changing social mores also came smaller families and changed relationships between parents and their children.

Another strong influence at this time was Marxism. After the generally primitivistic/irrationalist aspect of pre-World War I Modernism (which for many modernists precluded any attachment to merely political solutions) and the neoclassicism of the 1920s (as represented most famously by T. S. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky—which rejected popular solutions to modern problems), the rise of fascism, the Great Depression, and the march to war helped to radicalise a generation. Bertolt Brecht, W. H. Auden, André Breton, Louis Aragon and the philosophers Antonio Gramsci and Walter Benjamin are perhaps the most famous exemplars of this Modernist form of Marxism. There were, however, also modernists explicitly of 'the right', including Salvador Dalí, Wyndham Lewis, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, the Dutch author Menno ter Braak and others.[95]

Significant Modernist literary works continued to be created in the 1920s and 1930s, including further novels by Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, Robert Musil, and Dorothy Richardson. The American Modernist dramatist Eugene O'Neill's career began in 1914, but his major works appeared in the 1920s, 1930s and early 1940s. Two other significant Modernist dramatists writing in the 1920s and 1930s were Bertolt Brecht and Federico García Lorca. D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover was privately published in 1928, while another important landmark for the history of the modern novel came with the publication of William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury in 1929. In the 1930s, in addition to further major works by Faulkner, Samuel Beckett published his first major work, the novel Murphy (1938). Then in 1939 James Joyce's Finnegans Wake appeared. This is written in a largely idiosyncratic language, consisting of a mixture of standard English lexical items and neologistic multilingual puns and portmanteau words, which attempts to recreate the experience of sleep and dreams.[96] In poetry T. S. Eliot, E. E. Cummings, and Wallace Stevens were writing from the 1920s until the 1950s. While Modernist poetry in English is often viewed as an American phenomenon, with leading exponents including Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, H.D., and Louis Zukofsky, there were important British Modernist poets, including David Jones, Hugh MacDiarmid, Basil Bunting, and W. H. Auden. European Modernist poets include Federico García Lorca, Anna Akhmatova, Constantine Cavafy, and Paul Valéry.

The Modernist movement continued during this period in Soviet Russia. In 1930 composer Dimitri Shostakovich's (1906–1975) opera The Nose was premiered, in which he uses a montage of different styles, including folk music, popular song and atonality. Amongst his influences was Alban Berg's (1885–1935) opera Wozzeck (1925), which "had made a tremendous impression on Shostakovich when it was staged in Leningrad."[97] However, from 1932 Socialist realism began to oust Modernism in the Soviet Union,[98] and in 1936 Shostakovich was attacked and forced to withdraw his 4th Symphony.[99] Alban Berg wrote another significant, though incomplete, Modernist opera, Lulu, which premiered in 1937. Berg's Violin Concerto was first performed in 1935. Like Shostakovich, other composers faced difficulties in this period.

In Germany Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) was forced to flee to the U.S. when Hitler came to power in 1933, because of his Modernist atonal style as well as his Jewish ancestry.[100] His major works from this period are a Violin Concerto, Op. 36 (1934/36), and a Piano Concerto, Op. 42 (1942). Schoenberg also wrote tonal music in this period with the Suite for Strings in G major (1935) and the Chamber Symphony No. 2 in E♭ minor, Op. 38 (begun in 1906, completed in 1939).[100] During this time Hungarian Modernist Béla Bartók (1881–1945) produced a number of major works, including Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936) and the Divertimento for String Orchestra (1939), String Quartet No. 5 (1934), and No. 6 (his last, 1939). But he too left for the US in 1940, because of the rise of fascism in Hungary.[100] Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) continued writing in his neoclassical style during the 1930s and 1940s, writing works like the Symphony of Psalms (1930), Symphony in C (1940) and Symphony in Three Movements (1945). He also emigrated to the US because of World War II. Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992), however, served in the French army during the war and was imprisoned at Stalag VIII-A by the Germans, where he composed his famous Quatuor pour la fin du temps ("Quartet for the End of Time"). The quartet was first performed in January 1941 to an audience of prisoners and prison guards.[101]

In painting, during the 1920s and the 1930s and the Great Depression, modernism was defined by Surrealism, late Cubism, Bauhaus, De Stijl, Dada, German Expressionism, and Modernist and masterful color painters like Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard as well as the abstractions of artists like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky which characterized the European art scene. In Germany, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz and others politicized their paintings, foreshadowing the coming of World War II, while in America, modernism is seen in the form of American Scene painting and the social realism and regionalism movements that contained both political and social commentary dominated the art world. Artists like Ben Shahn, Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, George Tooker, John Steuart Curry, Reginald Marsh, and others became prominent. Modernism is defined in Latin America by painters Joaquín Torres-García from Uruguay and Rufino Tamayo from Mexico, while the muralist movement with Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Pedro Nel Gómez and Santiago Martínez Delgado, and Symbolist paintings by Frida Kahlo, began a renaissance of the arts for the region, characterized by a freer use of color and an emphasis on political messages.

Diego Rivera is perhaps best known by the public world for his 1933 mural, Man at the Crossroads, in the lobby of the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. When his patron Nelson Rockefeller discovered that the mural included a portrait of Vladimir Lenin and other communist imagery, he fired Rivera, and the unfinished work was eventually destroyed by Rockefeller's staff. Frida Kahlo's works are often characterized by their stark portrayals of pain. Kahlo was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in her paintings' bright colors and dramatic symbolism. Christian and Jewish themes are often depicted in her work as well; she combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition, which were often bloody and violent. Frida Kahlo's Symbolist works relate strongly to Surrealism and to the magic realism movement in literature.

Political activism was an important piece of David Siqueiros' life, and frequently inspired him to set aside his artistic career. His art was deeply rooted in the Mexican Revolution. The period from the 1920s to the 1950s is known as the Mexican Renaissance, and Siqueiros was active in the attempt to create an art that was at once Mexican and universal. The young Jackson Pollock attended the workshop and helped build floats for the parade.

During the 1930s radical leftist politics characterized many of the artists connected to Surrealism, including Pablo Picasso.[102] On 26 April 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, the Basque town of Gernika was bombed by Nazi Germany's Luftwaffe. The Germans were attacking to support the efforts of Francisco Franco to overthrow the Basque government and the Spanish Republican government. Pablo Picasso painted his mural-sized Guernica to commemorate the horrors of the bombing.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s and through the years of World War II, American art was characterized by social realism and American Scene painting, in the work of Grant Wood, Edward Hopper, Ben Shahn, Thomas Hart Benton, and several others. Nighthawks (1942) is a painting by Edward Hopper that portrays people sitting in a downtown diner late at night. It is not only Hopper's most famous painting, but one of the most recognizable in American art. The scene was inspired by a diner in Greenwich Village. Hopper began painting it immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After this event there was a large feeling of gloominess over the country, a feeling that is portrayed in the painting. The urban street is empty outside the diner, and inside none of the three patrons is apparently looking or talking to the others but instead is lost in their own thoughts. This portrayal of modern urban life as empty or lonely is a common theme throughout Hopper's work.

American Gothic is a painting by Grant Wood from 1930. Portraying a pitchfork-holding farmer and a younger woman in front of a house of Carpenter Gothic style, it is one of the most familiar images in 20th-century American art. Art critics had favorable opinions about the painting; like Gertrude Stein and Christopher Morley, they assumed the painting was meant to be a satire of rural small-town life. It was thus seen as part of the trend towards increasingly critical depictions of rural America, along the lines of Sherwood Anderson's 1919 Winesburg, Ohio, Sinclair Lewis's 1920 Main Street, and Carl Van Vechten's The Tattooed Countess in literature.[103] However, with the onset of the Great Depression, the painting came to be seen as a depiction of steadfast American pioneer spirit.

The situation for artists in Europe during the 1930s deteriorated rapidly as the Nazis' power in Germany and across Eastern Europe increased. Degenerate art was a term adopted by the Nazi regime in Germany for virtually all modern art. Such art was banned on the grounds that it was un-German or Jewish Bolshevist in nature, and those identified as degenerate artists were subjected to sanctions. These included being dismissed from teaching positions, being forbidden to exhibit or to sell their art, and in some cases being forbidden to produce art entirely. Degenerate Art was also the title of an exhibition, mounted by the Nazis in Munich in 1937. The climate became so hostile for artists and art associated with modernism and abstraction that many left for the Americas. German artist Max Beckmann and scores of others fled Europe for New York. In New York City a new generation of young and exciting Modernist painters led by Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and others were just beginning to come of age.

Arshile Gorky's portrait of someone who might be Willem de Kooning is an example of the evolution of abstract expressionism from the context of figure painting, cubism and surrealism. Along with his friends de Kooning and John D. Graham, Gorky created biomorphically shaped and abstracted figurative compositions that by the 1940s evolved into totally abstract paintings. Gorky's work seems to be a careful analysis of memory, emotion and shape, using line and color to express feeling and nature.

After World War II

While The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature states that modernism ended by c. 1939[104] with regard to British and American literature, "When (if) Modernism petered out and postmodernism began has been contested almost as hotly as when the transition from Victorianism to Modernism occurred."[105] Clement Greenberg sees modernism ending in the 1930s, with the exception of the visual and performing arts,[31] but with regard to music, Paul Griffiths notes that, while Modernism "seemed to be a spent force" by the late 1920s, after World War II, "a new generation of composers—Boulez, Barraqué, Babbitt, Nono, Stockhausen, Xenakis" revived modernism".[106] In fact many literary modernists lived into the 1950s and 1960s, though generally they were no longer producing major works. The term "late modernism" is also sometimes applied to Modernist works published after 1930.[107][108] Among modernists (or late modernists) still publishing after 1945 were Wallace Stevens, Gottfried Benn, T. S. Eliot, Anna Akhmatova, William Faulkner, Dorothy Richardson, John Cowper Powys, and Ezra Pound. Basil Bunting, born in 1901, published his most important Modernist poem Briggflatts in 1965. In addition, Hermann Broch's The Death of Virgil was published in 1945 and Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus in 1947. Samuel Beckett, who died in 1989, has been described as a "later Modernist".[109] Beckett is a writer with roots in the expressionist tradition of Modernism, who produced works from the 1930s until the 1980s, including Molloy (1951), Waiting for Godot (1953), Happy Days (1961), and Rockaby (1981). The terms "minimalist" and "post-Modernist" have also been applied to his later works.[110] The poets Charles Olson (1910–1970) and J. H. Prynne (born 1936) are among the writers in the second half of the 20th century who have been described as late modernists.[111]

More recently the term "late modernism" has been redefined by at least one critic and used to refer to works written after 1945, rather than 1930. With this usage goes the idea that the ideology of modernism was significantly re-shaped by the events of World War II, especially the Holocaust and the dropping of the atom bomb.[112]

The postwar period left the capitals of Europe in upheaval with an urgency to economically and physically rebuild and to politically regroup. In Paris (the former center of European culture and the former capital of the art world) the climate for art was a disaster. Important collectors, dealers, and Modernist artists, writers, and poets had fled Europe for New York and America. The surrealists and modern artists from every cultural center of Europe had fled the onslaught of the Nazis for safe haven in the United States. Many of those who did not flee perished. A few artists, notably Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Pierre Bonnard, remained in France and survived.

The 1940s in New York City heralded the triumph of American abstract expressionism, a Modernist movement that combined lessons learned from Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, surrealism, Joan Miró, cubism, Fauvism, and early modernism via great teachers in America like Hans Hofmann and John D. Graham. American artists benefited from the presence of Piet Mondrian, Fernand Léger, Max Ernst and the André Breton group, Pierre Matisse's gallery, and Peggy Guggenheim's gallery The Art of This Century, as well as other factors.

Paris, moreover, recaptured much of its luster in the 1950s and 60s as the center of a machine art florescence, with both of the leading machine art sculptors Jean Tinguely and Nicolas Schöffer having moved there to launch their careers—and which florescence, in light of the technocentric character of modern life, may well have a particularly long lasting influence.[113]

Theatre of the Absurd

The term "Theatre of the Absurd" is applied to plays, written primarily by Europeans, that express the belief that human existence has no meaning or purpose and therefore all communication breaks down. Logical construction and argument gives way to irrational and illogical speech and to its ultimate conclusion, silence.[114] While there are significant precursors, including Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), the Theatre of the Absurd is generally seen as beginning in the 1950s with the plays of Samuel Beckett.

Critic Martin Esslin coined the term in his 1960 essay "Theatre of the Absurd". He related these plays based on a broad theme of the Absurd, similar to the way Albert Camus uses the term in his 1942 essay, The Myth of Sisyphus.[115] The Absurd in these plays takes the form of man's reaction to a world apparently without meaning, and/or man as a puppet controlled or menaced by invisible outside forces. Though the term is applied to a wide range of plays, some characteristics coincide in many of the plays: broad comedy, often similar to vaudeville, mixed with horrific or tragic images; characters caught in hopeless situations forced to do repetitive or meaningless actions; dialogue full of clichés, wordplay, and nonsense; plots that are cyclical or absurdly expansive; either a parody or dismissal of realism and the concept of the "well-made play".

Playwrights commonly associated with the Theatre of the Absurd include Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), Eugène Ionesco (1909–1994), Jean Genet (1910–1986), Harold Pinter (1930–2008), Tom Stoppard (born 1937), Alexander Vvedensky (1904–1941), Daniil Kharms (1905–1942), Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921–1990), Alejandro Jodorowsky (born 1929), Fernando Arrabal (born 1932), Václav Havel (1936–2011) and Edward Albee (1928–2016).

Pollock and abstract influences

During the late 1940s Jackson Pollock's radical approach to painting revolutionized the potential for all contemporary art that followed him. To some extent Pollock realized that the journey toward making a work of art was as important as the work of art itself. Like Pablo Picasso's innovative reinventions of painting and sculpture in the early 20th century via Cubism and constructed sculpture, Pollock redefined the way art is made. His move away from easel painting and conventionality was a liberating signal to the artists of his era and to all who came after. Artists realized that Jackson Pollock's process—placing unstretched raw canvas on the floor where it could be attacked from all four sides using artistic and industrial materials; dripping and throwing linear skeins of paint; drawing, staining, and brushing; using imagery and nonimagery—essentially blasted artmaking beyond any prior boundary. Abstract expressionism generally expanded and developed the definitions and possibilities available to artists for the creation of new works of art. The other abstract expressionists followed Pollock's breakthrough with new breakthroughs of their own. In a sense the innovations of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, Hans Hofmann, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Motherwell, Peter Voulkos and others opened the floodgates to the diversity and scope of all the art that followed them. Rereadings into abstract art by art historians such as Linda Nochlin,[116] Griselda Pollock[117] and Catherine de Zegher[118] critically show, however, that pioneering women artists who produced major innovations in modern art had been ignored by official accounts of its history.

International figures from British art

Henry Moore (1898–1986) emerged after World War II as Britain's leading sculptor. He was best known for his semi-abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. His forms are usually abstractions of the human figure, typically depicting mother-and-child or reclining figures, usually suggestive of the female body, apart from a phase in the 1950s when he sculpted family groups. His forms are generally pierced or contain hollow spaces.

In the 1950s, Moore began to receive increasingly significant commissions, including a reclining figure for the UNESCO building in Paris in 1958.[119] With many more public works of art, the scale of Moore's sculptures grew significantly. The last three decades of Moore's life continued in a similar vein, with several major retrospectives taking place around the world, notably a prominent exhibition in the summer of 1972 in the grounds of the Forte di Belvedere overlooking Florence. By the end of the 1970s, there were some 40 exhibitions a year featuring his work. On the campus of the University of Chicago in December 1967, 25 years to the minute after the team of physicists led by Enrico Fermi achieved the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, Moore's Nuclear Energy was unveiled.[120][121] Also in Chicago, Moore commemorated science with a large bronze sundial, locally named Man Enters the Cosmos (1980), which was commissioned to recognise the space exploration program.[122]

The "London School" of figurative painters, including Francis Bacon (1909–1992), Lucian Freud (1922–2011), Frank Auerbach (born 1931), Leon Kossoff (born 1926), and Michael Andrews (1928–1995), have received widespread international recognition.[123]

Francis Bacon was an Irish-born British figurative painter known for his bold, graphic and emotionally raw imagery.[124] His painterly but abstracted figures typically appear isolated in glass or steel geometrical cages set against flat, nondescript backgrounds. Bacon began painting during his early 20s but worked only sporadically until his mid-30s. His breakthrough came with the 1944 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion which sealed his reputation as a uniquely bleak chronicler of the human condition.[125] His output can be crudely described as consisting of sequences or variations on a single motif; beginning with the 1940s male heads isolated in rooms, the early 1950s screaming popes, and mid to late 1950s animals and lone figures suspended in geometric structures. These were followed by his early 1960s modern variations of the crucifixion in the triptych format. From the mid-1960s to early 1970s, Bacon mainly produced strikingly compassionate portraits of friends. Following the suicide of his lover George Dyer in 1971, his art became more personal, inward-looking, and preoccupied with themes and motifs of death. During his lifetime, Bacon was equally reviled and acclaimed.[126]

Lucian Freud was a German-born British painter, known chiefly for his thickly impastoed portrait and figure paintings, who was widely considered the pre-eminent British artist of his time.[127][128][129][130] His works are noted for their psychological penetration, and for their often discomforting examination of the relationship between artist and model.[131] According to William Grimes of The New York Times, "Lucien Freud and his contemporaries transformed figure painting in the 20th century. In paintings like Girl with a White Dog (1951–1952),[132] Freud put the pictorial language of traditional European painting in the service of an anti-romantic, confrontational style of portraiture that stripped bare the sitter's social facade. Ordinary people—many of them his friends—stared wide-eyed from the canvas, vulnerable to the artist's ruthless inspection."[127]

In the 1960s after abstract expressionism

In abstract painting during the 1950s and 1960s several new directions like hard-edge painting and other forms of geometric abstraction began to appear in artist studios and in radical avant-garde circles as a reaction against the subjectivism of abstract expressionism. Clement Greenberg became the voice of post-painterly abstraction when he curated an influential exhibition of new painting that toured important art museums throughout the United States in 1964. color field painting, hard-edge painting and lyrical abstraction[133] emerged as radical new directions.

By the late 1960s however, postminimalism, process art and Arte Povera[134] also emerged as revolutionary concepts and movements that encompassed both painting and sculpture, via lyrical abstraction and the postminimalist movement, and in early conceptual art.[134] Process art as inspired by Pollock enabled artists to experiment with and make use of a diverse encyclopedia of style, content, material, placement, sense of time, and plastic and real space. Nancy Graves, Ronald Davis, Howard Hodgkin, Larry Poons, Jannis Kounellis, Brice Marden, Colin McCahon, Bruce Nauman, Richard Tuttle, Alan Saret, Walter Darby Bannard, Lynda Benglis, Dan Christensen, Larry Zox, Ronnie Landfield, Eva Hesse, Keith Sonnier, Richard Serra, Pat Lipsky, Sam Gilliam, Mario Merz and Peter Reginato were some of the younger artists who emerged during the era of late modernism that spawned the heyday of the art of the late 1960s.[135]

Pop art

In 1962 the Sidney Janis Gallery mounted The New Realists, the first major pop art group exhibition in an uptown art gallery in New York City. Janis mounted the exhibition in a 57th Street storefront near his gallery. The show sent shockwaves through the New York School and reverberated worldwide. Earlier in England in 1958 the term "Pop Art" was used by Lawrence Alloway to describe paintings that celebrated the consumerism of the post World War II era. This movement rejected abstract expressionism and its focus on the hermeneutic and psychological interior in favor of art that depicted and often celebrated material consumer culture, advertising, and the iconography of the mass production age. The early works of David Hockney and the works of Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi (who created the groundbreaking I was a Rich Man's Plaything, 1947) are considered seminal examples in the movement. Meanwhile, in the downtown scene in New York's East Village 10th Street galleries, artists were formulating an American version of pop art. Claes Oldenburg had his storefront, and the Green Gallery on 57th Street began to show the works of Tom Wesselmann and James Rosenquist. Later Leo Castelli exhibited the works of other American artists, including those of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein for most of their careers. There is a connection between the radical works of Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, the rebellious Dadaists with a sense of humor, and pop artists like Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein, whose paintings reproduce the look of Ben-Day dots, a technique used in commercial reproduction.

Minimalism

Minimalism describes movements in various forms of art and design, especially visual art and music, wherein artists intend to expose the essence or identity of a subject through eliminating all nonessential forms, features, or concepts. Minimalism is any design or style wherein the simplest and fewest elements are used to create the maximum effect.

As a specific movement in the arts it is identified with developments in post–World War II Western art, most strongly with American visual arts in the 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with this movement include Donald Judd, John McCracken, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Ronald Bladen, Anne Truitt, and Frank Stella.[136] It derives from the reductive aspects of modernism and is often interpreted as a reaction against Abstract expressionism and a bridge to Postminimal art practices. By the early 1960s minimalism emerged as an abstract movement in art (with roots in the geometric abstraction of Kazimir Malevich,[137] the Bauhaus and Piet Mondrian) that rejected the idea of relational and subjective painting, the complexity of abstract expressionist surfaces, and the emotional zeitgeist and polemics present in the arena of action painting. Minimalism argued that extreme simplicity could capture all of the sublime representation needed in art. Minimalism is variously construed either as a precursor to postmodernism, or as a postmodern movement itself. In the latter perspective, early minimalism yielded advanced Modernist works, but the movement partially abandoned this direction when some artists like Robert Morris changed direction in favor of the anti-form movement.

Hal Foster, in his essay The Crux of Minimalism,[138] examines the extent to which Donald Judd and Robert Morris both acknowledge and exceed Greenbergian Modernism in their published definitions of minimalism.[138] He argues that minimalism is not a "dead end" of Modernism, but a "paradigm shift toward postmodern practices that continue to be elaborated today."[138]

Minimal music

The terms have expanded to encompass a movement in music that features such repetition and iteration as those of the compositions of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and John Adams. Minimalist compositions are sometimes known as systems music. The term 'minimal music' is generally used to describe a style of music that developed in America in the late 1960s and 1970s; and that was initially connected with the composers.[139] The minimalism movement originally involved some composers, and other lesser known pioneers included Pauline Oliveros, Phill Niblock, and Richard Maxfield. In Europe, the music of Louis Andriessen, Karel Goeyvaerts, Michael Nyman, Howard Skempton, Eliane Radigue, Gavin Bryars, Steve Martland, Henryk Górecki, Arvo Pärt and John Tavener.

Postminimalism

In the late 1960s Robert Pincus-Witten[134] coined the term "postminimalism" to describe minimalist-derived art which had content and contextual overtones that minimalism rejected. The term was applied by Pincus-Whitten to the work of Eva Hesse, Keith Sonnier, Richard Serra and new work by former minimalists Robert Smithson, Robert Morris, Sol LeWitt, Barry Le Va, and others. Other minimalists including Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Agnes Martin, John McCracken and others continued to produce late Modernist paintings and sculpture for the remainders of their careers.

Since then, many artists have embraced minimal or postminimal styles, and the label "Postmodern" has been attached to them.

Collage, assemblage, installations

Related to abstract expressionism was the emergence of combining manufactured items with artist materials, moving away from previous conventions of painting and sculpture. The work of Robert Rauschenberg exemplifies this trend. His "combines" of the 1950s were forerunners of pop art and installation art, and used assemblages of large physical objects, including stuffed animals, birds and commercial photographs. Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Larry Rivers, John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, George Segal, Jim Dine, and Edward Kienholz were among important pioneers of both abstraction and pop art. Creating new conventions of art-making, they made acceptable in serious contemporary art circles the radical inclusion in their works of unlikely materials. Another pioneer of collage was Joseph Cornell, whose more intimately scaled works were seen as radical because of both his personal iconography and his use of found objects.

Neo-Dada

In the early 20th century Marcel Duchamp submitted for exhibition a urinal as a sculpture.[140] He professed his intent that people look at the urinal as if it were a work of art because he said it was a work of art. He referred to his work as "readymades". Fountain was a urinal signed with the pseudonym "R. Mutt", the exhibition of which shocked the art world in 1917. This and Duchamp's other works are generally labelled as Dada. Duchamp can be seen as a precursor to conceptual art, other famous examples being John Cage's 4′33″, which is four minutes and thirty three seconds of silence, and Rauschenberg's Erased de Kooning Drawing. Many conceptual works take the position that art is the result of the viewer viewing an object or act as art, not of the intrinsic qualities of the work itself. In choosing "an ordinary article of life" and creating "a new thought for that object" Duchamp invited onlookers to view Fountain as a sculpture.[141]

Marcel Duchamp famously gave up "art" in favor of chess. Avant-garde composer David Tudor created a piece, Reunion (1968), written jointly with Lowell Cross, that features a chess game in which each move triggers a lighting effect or projection. Duchamp and Cage played the game at the work's premier.[142]

Steven Best and Douglas Kellner identify Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns as part of the transitional phase, influenced by Duchamp, between Modernism and Postmodernism. Both used images of ordinary objects, or the objects themselves, in their work, while retaining the abstraction and painterly gestures of high Modernism.[143]

Performance and happenings

During the late 1950s and 1960s artists with a wide range of interests began to push the boundaries of contemporary art. Yves Klein in France, Carolee Schneemann, Yayoi Kusama, Charlotte Moorman and Yoko Ono in New York City, and Joseph Beuys, Wolf Vostell and Nam June Paik in Germany were pioneers of performance-based works of art. Groups like The Living Theatre with Julian Beck and Judith Malina collaborated with sculptors and painters creating environments, radically changing the relationship between audience and performer, especially in their piece Paradise Now. The Judson Dance Theater, located at the Judson Memorial Church, New York; and the Judson dancers, notably Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Elaine Summers, Sally Gross, Simonne Forti, Deborah Hay, Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton and others; collaborated with artists Robert Morris, Robert Whitman, John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, and engineers like Billy Klüver. Park Place Gallery was a center for musical performances by electronic composers Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and other notable performance artists including Joan Jonas.

These performances were intended as works of a new art form combining sculpture, dance, and music or sound, often with audience participation. They were characterized by the reductive philosophies of minimalism and the spontaneous improvisation and expressivity of abstract expressionism. Images of Schneeman's performances of pieces meant to shock are occasionally used to illustrate these kinds of art, and she is often seen photographed while performing her piece Interior Scroll. However, according to modernist philosophy surrounding performance art, it is cross-purposes to publish images of her performing this piece, for performance artists reject publication entirely: the performance itself is the medium. Thus, other media cannot illustrate performance art; performance is momentary, evanescent, and personal, not for capturing; representations of performance art in other media, whether by image, video, narrative or otherwise, select certain points of view in space or time or otherwise involve the inherent limitations of each medium. The artists deny that recordings illustrate the medium of performance as art.

During the same period, various avant-garde artists created Happenings, mysterious and often spontaneous and unscripted gatherings of artists and their friends and relatives in various specified locations, often incorporating exercises in absurdity, physicality, costuming, spontaneous nudity, and various random or seemingly disconnected acts. Notable creators of happenings included Allan Kaprow—who first used the term in 1958,[145] Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Red Grooms, and Robert Whitman.[146]

Intermedia, multi-media

Another trend in art which has been associated with the term postmodern is the use of a number of different media together. Intermedia is a term coined by Dick Higgins and meant to convey new art forms along the lines of Fluxus, concrete poetry, found objects, performance art, and computer art. Higgins was the publisher of the Something Else Press, a concrete poet married to artist Alison Knowles and an admirer of Marcel Duchamp. Ihab Hassan includes "Intermedia, the fusion of forms, the confusion of realms," in his list of the characteristics of postmodern art.[147] One of the most common forms of "multi-media art" is the use of video-tape and CRT monitors, termed video art. While the theory of combining multiple arts into one art is quite old, and has been revived periodically, the postmodern manifestation is often in combination with performance art, where the dramatic subtext is removed, and what is left is the specific statements of the artist in question or the conceptual statement of their action.

Fluxus

Fluxus was named and loosely organized in 1962 by George Maciunas (1931–1978), a Lithuanian-born American artist. Fluxus traces its beginnings to John Cage's 1957 to 1959 Experimental Composition classes at The New School for Social Research in New York City. Many of his students were artists working in other media with little or no background in music. Cage's students included Fluxus founding members Jackson Mac Low, Al Hansen, George Brecht and Dick Higgins.

Fluxus encouraged a do-it-yourself aesthetic and valued simplicity over complexity. Like Dada before it, Fluxus included a strong current of anti-commercialism and an anti-art sensibility, disparaging the conventional market-driven art world in favor of an artist-centered creative practice. Fluxus artists preferred to work with whatever materials were at hand, and either created their own work or collaborated in the creation process with their colleagues.

Andreas Huyssen criticises attempts to claim Fluxus for Postmodernism as "either the master-code of postmodernism or the ultimately unrepresentable art movement—as it were, postmodernism's sublime."[148] Instead he sees Fluxus as a major Neo-Dadaist phenomena within the avant-garde tradition. It did not represent a major advance in the development of artistic strategies, though it did express a rebellion against "the administered culture of the 1950s, in which a moderate, domesticated modernism served as ideological prop to the Cold War."[148]

Avant-garde popular music

Modernism had an uneasy relationship with popular forms of music (both in form and aesthetic) while rejecting popular culture.[149] Despite this, Stravinsky used jazz idioms on his pieces like "Ragtime" from his 1918 theatrical work Histoire du Soldat and 1945's Ebony Concerto.[150]

In the 1960s, as popular music began to gain cultural importance and question its status as commercial entertainment, musicians began to look to the post-war avant-garde for inspiration.[151] In 1959, music producer Joe Meek recorded I Hear a New World (1960), which Tiny Mix Tapes' Jonathan Patrick calls a "seminal moment in both electronic music and avant-pop history [...] a collection of dreamy pop vignettes, adorned with dubby echoes and tape-warped sonic tendrils" which would be largely ignored at the time.[152] Other early avant-pop productions included the Beatles's 1966 song "Tomorrow Never Knows", which incorporated techniques from musique concrète, avant-garde composition, Indian music, and electro-acoustic sound manipulation into a 3-minute pop format, and the Velvet Underground's integration of La Monte Young's minimalist and drone music ideas, beat poetry, and 1960s pop art.[151]

Late period

The continuation of abstract expressionism, color field painting, lyrical abstraction, geometric abstraction, minimalism, abstract illusionism, process art, pop art, postminimalism, and other late 20th-century Modernist movements in both painting and sculpture continued through the first decade of the 21st century and constitute radical new directions in those mediums.[153][154][155]

At the turn of the 21st century, well-established artists such as Sir Anthony Caro, Lucian Freud, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Agnes Martin, Al Held, Ellsworth Kelly, Helen Frankenthaler, Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, James Rosenquist, Alex Katz, Philip Pearlstein, and younger artists including Brice Marden, Chuck Close, Sam Gilliam, Isaac Witkin, Sean Scully, Mahirwan Mamtani, Joseph Nechvatal, Elizabeth Murray, Larry Poons, Richard Serra, Walter Darby Bannard, Larry Zox, Ronnie Landfield, Ronald Davis, Dan Christensen, Pat Lipsky, Joel Shapiro, Tom Otterness, Joan Snyder, Ross Bleckner, Archie Rand, Susan Crile, and others continued to produce vital and influential paintings and sculpture.

Modern architecture

Many skyscrapers in Hong Kong and Frankfurt have been inspired by Le Corbusier and modernist architecture, and his style is still used as influence for buildings worldwide.[156]

Modernism in Africa and Asia

Peter Kalliney suggests that "Modernist concepts, especially aesthetic autonomy, were fundamental to the literature of decolonization in anglophone Africa."[157] In his opinion, Rajat Neogy, Christopher Okigbo, and Wole Soyinka, were among the writers who "repurposed modernist versions of aesthetic autonomy to declare their freedom from colonial bondage, from systems of racial discrimination, and even from the new postcolonial state".[158]

The terms "modernism" and "modernist", according to scholar William J. Tyler, "have only recently become part of the standard discourse in English on modern Japanese literature and doubts concerning their authenticity vis-a-vis Western European modernism remain". Tyler finds this odd, given "the decidedly modern prose" of such "well-known Japanese writers as Kawabata Yasunari, Nagai Kafu, and Jun'ichirō Tanizaki". However, "scholars in the visual and fine arts, architecture, and poetry readily embraced "modanizumu" as a key concept for describing and analyzing Japanese culture in the 1920s and 1930s".[159] In 1924, various young Japanese writers, including Kawabata and Riichi Yokomitsu started a literary journal Bungei Jidai ("The Artistic Age"). This journal was "part of an 'art for art's sake' movement, influenced by European Cubism, Expressionism, Dada, and other modernist styles".[160]

Japanese modernist architect Kenzō Tange (1913–2005) was one of the most significant architects of the 20th century, combining traditional Japanese styles with modernism, and designing major buildings on five continents. Tange was also an influential patron of the Metabolist movement. He said: "It was, I believe, around 1959 or at the beginning of the sixties that I began to think about what I was later to call structuralism",[161] He was influenced from an early age by the Swiss modernist, Le Corbusier, Tange gained international recognition in 1949 when he won the competition for the design of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

In China the "New Sensationists" (新感觉派, Xīn Gǎnjué Pài) were a group of writers based in Shanghai who in the 1930s and 1940s were influenced, to varying degrees, by Western and Japanese modernism. They wrote fiction that was more concerned with the unconscious and with aesthetics than with politics or social problems. Among these writers were Mu Shiying and Shi Zhecun.

In India, the Progressive Artists' Group was a group of modern artists, mainly based in Mumbai, India formed in 1947. Though it lacked any particular style, it synthesised Indian art with European and North America influences from the first half of the 20th century, including Post-Impressionism, Cubism and Expressionism.

Differences between modernism and postmodernism

By the early 1980s the Postmodern movement in art and architecture began to establish its position through various conceptual and intermedia formats. Postmodernism in music and literature began to take hold earlier. In music, postmodernism is described in one reference work as a "term introduced in the 1970s",[162] while in British literature, The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature sees modernism "ceding its predominance to postmodernism" as early as 1939.[104] However, dates are highly debatable, especially as according to Andreas Huyssen: "one critic's postmodernism is another critic's modernism."[163] This includes those who are critical of the division between the two and see them as two aspects of the same movement, and believe that late Modernism continues.[163]

Modernism is an encompassing label for a wide variety of cultural movements. Postmodernism is essentially a centralized movement that named itself, based on sociopolitical theory, although the term is now used in a wider sense to refer to activities from the 20th century onwards which exhibit awareness of and reinterpret the modern.[164][165][166]

Postmodern theory asserts that the attempt to canonise Modernism "after the fact" is doomed to undisambiguable contradictions.[167]