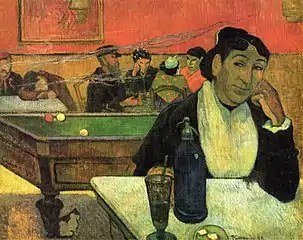

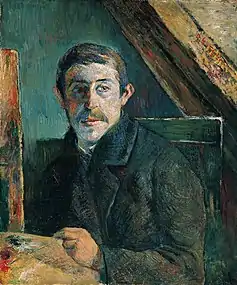

Paul Gauguin | |

|---|---|

Gauguin in 1891 | |

| Born | Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin 7 June 1848 Paris, French Second Republic |

| Died | 8 May 1903 (aged 54) |

| Known for | |

| Movement | |

| Spouses |

|

| Signature | |

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (UK: /ˈɡoʊɡæ̃/, US: /ɡoʊˈɡæ̃/, French: [øʒɛn ɑ̃ʁi pɔl ɡoɡɛ̃]; 7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903) was a French Post-Impressionist artist. Unappreciated until after his death, Gauguin is now recognized for his experimental use of colour and Synthetist style that were distinct from Impressionism. Toward the end of his life, he spent ten years in French Polynesia. The paintings from this time depict people or landscapes from that region.

His work was influential on the French avant-garde and many modern artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, and he is well known for his relationship with Vincent and Theo van Gogh. Gauguin's art became popular after his death, partially from the efforts of dealer Ambroise Vollard, who organized exhibitions of his work late in his career and assisted in organizing two important posthumous exhibitions in Paris.[1][2]

Gauguin was an important figure in the Symbolist movement as a painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramist, and writer. His expression of the inherent meaning of the subjects in his paintings, under the influence of the cloisonnist style, paved the way for Primitivism and the return to the pastoral. He was also an influential practitioner of wood engraving and woodcuts as art forms.[3][4] In the 21st century, Gauguin's Primitivist representations of Polynesian cultures and peoples, the artist's sexual relationships with teenage Tahitian girls, and the legacy of European colonialism in his work have been a subject of renewed scholarly debate and controversy.[5][6][7]

Biography

Family history and early life

Gauguin was born in Paris to Clovis Gauguin and Aline Chazal on 7 June 1848, the year of revolutionary upheavals throughout Europe. His father, a 34-year-old liberal journalist from a family of entrepreneurs in Orléans,[8] was compelled to flee France when the newspaper for which he wrote was suppressed by French authorities.[9][10] Gauguin's mother was the 22-year-old daughter of André Chazal, an engraver, and Flora Tristan, an author and activist in early socialist movements. Their union ended when André assaulted his wife Flora and was sentenced to prison for attempted murder.[11]

Paul Gauguin's maternal grandmother, Flora Tristan, was the illegitimate daughter of Thérèse Laisnay and Don Mariano de Tristan Moscoso. Details of Thérèse's family background are not known; Don Mariano came from an aristocratic Spanish family from the Peruvian city of Arequipa. He was an officer of the Dragoons.[12] Members of the wealthy Tristan Moscoso family held powerful positions in Peru.[13] Nonetheless, Don Mariano's unexpected death plunged his mistress and daughter Flora into poverty.[14] When Flora's marriage with André failed, she petitioned for and obtained a small monetary settlement from her father's Peruvian relatives. She sailed to Peru in hopes of enlarging her share of the Tristan Moscoso family fortune. This never materialized; but she successfully published a popular travelogue of her experiences in Peru which launched her literary career in 1838. An active supporter of early socialist societies, Gauguin's maternal grandmother helped to lay the foundations for the 1848 revolutionary movements. Placed under surveillance by French police and suffering from overwork, she died in 1844.[15] Her grandson Paul "idolized his grandmother, and kept copies of her books with him to the end of his life".[16]

In 1850, Clovis Gauguin departed for Peru with his wife Aline and young children in hopes of continuing his journalistic career under the auspices of his wife's South American relations.[17] He died of a heart attack en route, and Aline arrived in Peru as a widow with the 18-month-old Paul and his 21⁄2 year-old sister, Marie. Gauguin's mother was welcomed by her paternal granduncle, whose son-in-law, José Rufino Echenique, would shortly assume the presidency of Peru.[18] To the age of six, Paul enjoyed a privileged upbringing, attended by nursemaids and servants. He retained a vivid memory of that period of his childhood which instilled "indelible impressions of Peru that haunted him the rest of his life".[19][20]

Gauguin's idyllic childhood ended abruptly when his family mentors fell from political power during Peruvian civil conflicts in 1854. Aline returned to France with her children, leaving Paul with his paternal grandfather, Guillaume Gauguin, in Orléans. Deprived by the Peruvian Tristan Moscoso clan of a generous annuity arranged by her granduncle, Aline settled in Paris to work as a dressmaker.[21]

Education and first job

After attending a couple of local schools, Gauguin was sent to the prestigious Catholic boarding school Petit Séminaire de La Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin.[22] He spent three years at the school. At the age of 14, he entered the Loriol Institute in Paris, a naval preparatory school, before returning to Orléans to take his final year at the Lycée Jeanne D'Arc. Gauguin signed on as a pilot's assistant in the merchant marine. Three years later, he joined the French navy in which he served for two years.[23] His mother died on 7 July 1867, but he did not learn of it for several months until a letter from his sister Marie caught up with him in India.[24][25]

In 1871, Gauguin returned to Paris where he secured a job as a stockbroker. A close family friend, Gustave Arosa, got him a job at the Paris Bourse; Gauguin was 23. He became a successful Parisian businessman and remained one for the next 11 years. In 1879 he was earning 30,000 francs a year (about $145,000 in 2019 US dollars) as a stockbroker, and as much again in his dealings in the art market.[26][27] But in 1882 the Paris stock market crashed and the art market contracted. Gauguin's earnings deteriorated sharply and he eventually decided to pursue painting full-time.[28][29]

Marriage

In 1873, he married a Danish woman, Mette-Sophie Gad (1850–1920). Over the next ten years, they had five children: Émile (1874–1955); Aline (1877–1897); Clovis (1879–1900); Jean René (1881–1961); and Paul Rollon (1883–1961). By 1884, Gauguin had moved with his family to Copenhagen, Denmark, where he pursued a business career as a tarpaulin salesman. It was not a success: He could not speak Danish, and the Danes did not want French tarpaulins. Mette became the chief breadwinner, giving French lessons to trainee diplomats.[30]

His middle-class family and marriage fell apart after 11 years when Gauguin was driven to paint full-time. He returned to Paris in 1885, after his wife and her family asked him to leave because he had renounced the values they shared.[31][32] Gauguin's last physical contact with them was in 1891, and Mette eventually broke with him decisively in 1894.[33][34][35][36]

First paintings

In 1873, around the time he became a stockbroker, Gauguin began painting in his free time. His Parisian life centered on the 9th arrondissement of Paris. Gauguin lived at 15, rue la Bruyère.[37][38] Nearby were the cafés frequented by the Impressionists. Gauguin also visited galleries frequently and purchased work by emerging artists. He formed a friendship with Camille Pissarro[39] and visited him on Sundays to paint in his garden. Pissarro introduced him to various other artists. In 1877 Gauguin "moved downmarket and across the river to the poorer, newer, urban sprawls" of Vaugirard. Here, on the third floor at 8 rue Carcel, he had his first home with a studio.[38]

His close friend Émile Schuffenecker, a former stockbroker who also aspired to become an artist, lived close by. Gauguin showed paintings in Impressionist exhibitions held in 1881 and 1882 (earlier, a sculpture of his son Émile had been the only sculpture in the 4th Impressionist Exhibition of 1879). His paintings received dismissive reviews, although several of them, such as The Market Gardens of Vaugirard, are now highly regarded.[40][41]

In 1882, the stock market crashed and the art market contracted. Paul Durand-Ruel, the Impressionists' primary art dealer, was especially affected by the crash, and for a period of time stopped buying pictures from painters such as Gauguin. Gauguin's earnings contracted sharply, and over the next two years he slowly formulated his plans to become a full-time artist.[39] The following two summers, he painted with Pissarro and occasionally Paul Cézanne.

In October 1883, he wrote to Pissarro saying that he had decided to make his living from painting at all costs and asked for his help, which Pissarro at first readily provided. The following January, Gauguin moved with his family to Rouen, where they could live more cheaply and where he thought he had discerned opportunities when visiting Pissarro there the previous summer. However, the venture proved unsuccessful, and by the end of the year Mette and the children moved to Copenhagen, Gauguin following shortly after in November 1884, bringing with him his art collection, which subsequently remained in Copenhagen.[42][43]

Life in Copenhagen proved equally difficult, and their marriage grew strained. At Mette's urging, supported by her family, Gauguin returned to Paris the following year.[44][45]

The Market Gardens of Vaugirard, 1879, Smith College Museum of Art

The Market Gardens of Vaugirard, 1879, Smith College Museum of Art Winter Landscape, 1879, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Winter Landscape, 1879, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_116_x_81_cm%252C_Foundation_E.G._B%C3%BChrle.jpg.webp) Portrait of Madame Gauguin, c. 1880–81, Foundation E.G. Bührle, Zürich

Portrait of Madame Gauguin, c. 1880–81, Foundation E.G. Bührle, Zürich Garden in Vaugirard (Painter's Family in the Garden in Rue Carcel), 1881, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Garden in Vaugirard (Painter's Family in the Garden in Rue Carcel), 1881, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

France 1885–1886

After a brief period in Italy, spent in the small towns of San Salvo and Ururi, Gauguin returned to Paris in June 1885, accompanied by his six-year-old son Clovis. The other children remained with Mette in Copenhagen, where they had the support of family and friends while Mette herself was able to get work as a translator and French teacher. Gauguin initially found it difficult to re-enter the art world in Paris and spent his first winter back in real poverty, obliged to take a series of menial jobs. Clovis eventually fell ill and was sent to a boarding school, Gauguin's sister Marie providing the funds.[46][47] During this first year, Gauguin produced very little art. He exhibited 19 paintings and a wood relief at the eighth (and last) Impressionist exhibition in May 1886.[48]

Most of these paintings were earlier work from Rouen or Copenhagen and there was nothing really novel in the few new ones, although his Baigneuses à Dieppe ("Women Bathing") introduced what was to become a recurring motif, the woman in the waves. Nevertheless, Félix Bracquemond did purchase one of his paintings. This exhibition also established Georges Seurat as leader of the avant-garde movement in Paris. Gauguin contemptuously rejected Seurat's Neo-Impressionist Pointillist technique and later in the year broke decisively with Pissarro, who from that point on was rather antagonistic towards Gauguin.[49][50]

Gauguin spent the summer of 1886 in the artist's colony of Pont-Aven in Brittany. He was attracted in the first place because it was cheap to live there. However, he found himself an unexpected success with the young art students who flocked there in the summer. His naturally pugilistic temperament (he was both an accomplished boxer and fencer) was no impediment in the socially relaxed seaside resort. He was remembered during that period as much for his outlandish appearance as for his art. Amongst these new associates was Charles Laval, who would accompany Gauguin the following year to Panama and Martinique.[51][52]

That summer, he executed some pastel drawings of nude figures in the manner of Pissarro and those by Degas exhibited at the 1886 eighth Impressionist exhibition. He mainly painted landscapes such as La Bergère Bretonne ("The Breton Shepherdess"), in which the figure plays a subordinate role. His Jeunes Bretons au bain ("Young Breton Boys Bathing"), introducing a theme he returned to each time he visited Pont-Aven, is clearly indebted to Degas in its design and bold use of pure colour. The naive drawings of the English illustrator Randolph Caldecott, used to illustrate a popular guide-book on Brittany, had caught the imagination of the avant-garde student artists at Pont-Aven, anxious to free themselves from the conservatism of their academies, and Gauguin consciously imitated them in his sketches of Breton girls.[53] These sketches were later worked up into paintings back in his Paris studio. The most important of these is Four Breton Women, which shows a marked departure from his earlier Impressionist style as well as incorporating something of the naive quality of Caldecott's illustration, exaggerating features to the point of caricature.[52][54]

Gauguin, along with Émile Bernard, Charles Laval, Émile Schuffenecker and many others, re-visited Pont-Aven after his travels in Panama and Martinique. The bold use of pure colour and Symbolist choice of subject matter distinguish what is now called the Pont-Aven School. Disappointed with Impressionism, Gauguin felt that traditional European painting had become too imitative and lacked symbolic depth. By contrast, the art of Africa and Asia seemed to him full of mystic symbolism and vigour. There was a vogue in Europe at the time for the art of other cultures, especially that of Japan (Japonism). He was invited to participate in the 1889 exhibition organized by Les XX.

Women Bathing, 1885, National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

Women Bathing, 1885, National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo La Bergère Bretonne, 1886, Laing Art Gallery

La Bergère Bretonne, 1886, Laing Art Gallery Breton Girl, 1886, Burrell Collection, Glasgow

Breton Girl, 1886, Burrell Collection, Glasgow Breton Bather, 1886–87, Art Institute of Chicago

Breton Bather, 1886–87, Art Institute of Chicago

Cloisonnism and synthetism

Under the influence of folk art and Japanese prints, Gauguin's work evolved towards Cloisonnism, a style given its name by the critic Édouard Dujardin to describe Émile Bernard's method of painting with flat areas of colour and bold outlines, which reminded Dujardin of the Medieval cloisonné enameling technique. Gauguin was very appreciative of Bernard's art and of his daring with the employment of a style which suited Gauguin in his quest to express the essence of the objects in his art.[55]

In Gauguin's The Yellow Christ (1889), often cited as a quintessential Cloisonnist work, the image was reduced to areas of pure colour separated by heavy black outlines. In such works Gauguin paid little attention to classical perspective and boldly eliminated subtle gradations of colour, thereby dispensing with the two most characteristic principles of post-Renaissance painting. His painting later evolved towards Synthetism in which neither form nor colour predominate but each has an equal role.

The Yellow Christ (Le Christ jaune), 1889, Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

The Yellow Christ (Le Christ jaune), 1889, Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

Panama Canal

In 1887, Gauguin left France along with his friend, another young painter, Charles Laval. His dream was to purchase land of his own on the small Panamanian island of Taboga, where he stated he desired to live "on fish and fruit and for nothing… without anxiety for the day or for the morrow." By the time he reached the port city of Colón, Gauguin was out of money and found work as a laborer on the French construction of the Panama Canal. During this time, Gauguin penned letters to his wife, Mette, lamenting the arduous conditions: "I have to dig… from five-thirty in the morning to six in the evening, under the tropical sun and rain," he wrote. "At night I am devoured by mosquitoes." Meanwhile, Laval had been earning money by drawing portraits of canal officials, work which Gauguin detested since only portraits done in a lewd manner would sell.[56]

Gauguin held a profound contempt for Panama, and at one point was arrested in Panama City for urinating in public. Marched across town at gunpoint, Gauguin was ordered to pay a fine of four francs. After discovering that land on Taboga was priced far beyond reach (and after falling deathly ill on the island where he was subsequently interned in a yellow fever and malaria sanatorium),[57] he decided to leave Panama.[56]

Martinique

Later that same year, Gauguin and Laval spent the time from June to November near Saint Pierre on the Caribbean island of Martinique, a French colony. His thoughts and experiences during this time are recorded in his letters to his wife and his artist friend Emile Schuffenecker.[58] At the time, France had a policy of repatriation where if a citizen became broke or stranded on a French colony, the state would pay for the boat ride back. Upon leaving Panama, protected by the repatriation policy, Gauguin and Laval decided to disembark at the Martinique port of St. Pierre. Scholars disagree on whether Gauguin intentionally or spontaneously decided to stay on the island.

At first, the 'negro hut' in which they lived suited him, and he enjoyed watching people in their daily activities.[59] However, the weather in the summer was hot and the hut leaked in the rain. Gauguin also suffered dysentery and marsh fever. While in Martinique, he produced between 10 and 20 works (12 being the most common estimate), traveled widely and apparently came into contact with a small community of Indian immigrants; a contact that would later influence his art through the incorporation of Indian symbols. During his stay, the writer Lafcadio Hearn was also on the island.[60] His account provides an historical comparison to accompany Gauguin's images.

Gauguin finished 11 known paintings during his stay in Martinique, many of which seem to be derived from his hut. His letters to Schuffenecker express an excitement about the exotic location and natives represented in his paintings. Gauguin asserted that four of his paintings on the island were better than the rest.[61] The works as a whole are brightly coloured, loosely painted, outdoor figural scenes. Even though his time on the island was short, it surely was influential. He recycled some of his figures and sketches in later paintings, such as the motif in Among the Mangoes,[62] which is replicated on his fans. Rural and indigenous populations remained a popular subject in Gauguin's work after he left the island.

Huttes sous les arbres, 1887, Private collection, Washington

Huttes sous les arbres, 1887, Private collection, Washington Bord de Mer II, 1887, Private collection, Paris

Bord de Mer II, 1887, Private collection, Paris At the Pond, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

At the Pond, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam Conversation Tropiques (Négresses Causant), 1887, Private collection, Dallas

Conversation Tropiques (Négresses Causant), 1887, Private collection, Dallas Among the Mangoes (La Cueillette des Fruits), 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam[62]

Among the Mangoes (La Cueillette des Fruits), 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam[62]

Vincent and Theo van Gogh

.jpg.webp)

Gauguin's Martinique paintings were exhibited at his colour merchant Arsène Poitier's gallery. There they were seen and admired by Vincent van Gogh and his art dealer brother Theo, whose firm Goupil & Cie had dealings with Portier. Theo purchased three of Gauguin's paintings for 900 francs and arranged to have them hung at Goupil's, thus introducing Gauguin to wealthy clients. This arrangement with Goupil's continued past Theo's death in 1891. At the same time, Vincent and Gauguin became close friends (on Vincent's part it amounted to something akin to adulation) and they corresponded together on art, a correspondence that was instrumental in Gauguin formulating his philosophy of art.[63][64]

In 1888, at Theo's instigation, Gauguin and Vincent spent nine weeks painting together at Vincent's Yellow House in Arles in the South of France. Gauguin's relationship with Vincent proved fraught. Their relationship deteriorated and eventually Gauguin decided to leave. On the evening of 23 December 1888, according to a much later account of Gauguin's, Vincent confronted Gauguin with a straight razor. Later the same evening, he cut off his own left ear. He wrapped the severed tissue in newspaper and handed it to a woman who worked at a brothel Gauguin and Vincent had both visited, and asked her to "keep this object carefully, in remembrance of me". Vincent was hospitalized the following day and Gauguin left Arles.[65] They never saw each other again, but they continued to correspond, and in 1890 Gauguin went so far as to propose they form an artist studio in Antwerp.[66] An 1889 sculptural self-portrait Jug in the Form of a Head appears to reference Gauguin's traumatic relationship with Vincent.

Gauguin later claimed to have been instrumental in influencing Vincent van Gogh's development as a painter at Arles. While Vincent did briefly experiment with Gauguin's theory of "painting from the imagination" in paintings such as Memory of the Garden at Etten, it did not suit him and he quickly returned to painting from nature.[67][68]

Edgar Degas

Although Gauguin made some of his early strides in the world of art under Pissarro, Edgar Degas was Gauguin's most admired contemporary artist and a great influence on his work from the beginning, with his figures and interiors as well as a carved and painted medallion of singer Valérie Roumi.[69] He had a deep reverence for Degas' artistic dignity and tact.[70] It was Gauguin's healthiest, longest-lasting friendship, spanning his entire artistic career until his death.

In addition to being one of his earliest supporters, including buying Gauguin's work and persuading dealer Paul Durand-Ruel to do the same, there was never a public support for Gauguin more unwavering than from Degas.[71] Gauguin also purchased work from Degas in the early to mid-1870s and his own monotyping predilection was probably influenced by Degas' advancements in the medium.[72]

_(recto)%252C_1894%252C_NGA_11586.jpg.webp)

Gauguin's Durand-Ruel exhibition in November 1893, which Degas chiefly organized, received mixed reviews. Among the mocking were Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and former friend Pissarro. Degas, however, praised his work, purchasing Te faaturuma and admiring the exotic sumptuousness of Gauguin's conjured folklore.[73][74][75] In appreciation, Gauguin presented Degas with The Moon and the Earth, one of the exhibited paintings that had attracted the most hostile criticism.[76] Gauguin's late canvas Riders on the Beach (two versions) recalls Degas' horse pictures that he started in the 1860s, specifically Racetrack and Before the Race, testifying to his enduring effect on Gauguin.[77] Degas later purchased two paintings at Gauguin's 1895 auction to raise funds for his final trip to Tahiti. These were Vahine no te vi (Woman with a Mango) and the version Gauguin painted of Édouard Manet's Olympia.[76][78]

First visit to Tahiti

By 1890, Gauguin had conceived the project of making Tahiti his next artistic destination. A successful auction of paintings in Paris at the Hôtel Drouot in February 1891, along with other events such as a banquet and a benefit concert, provided the necessary funds.[79] The auction had been greatly helped by a flattering review from Octave Mirbeau, courted by Gauguin through Camille Pissarro.[80] After visiting his wife and children in Copenhagen, for what turned out to be the last time, Gauguin set sail for Tahiti on 1 April 1891, promising to return a rich man and make a fresh start.[81] His avowed intent was to escape European civilization and "everything that is artificial and conventional".[82][83] Nevertheless, he took care to take with him a collection of visual stimuli in the form of photographs, drawings and prints.[84][lower-alpha 1]

He spent the first three months in Papeete, the capital of the colony and already much influenced by French and European culture. His biographer Belinda Thomson observes that he must have been disappointed in his vision of a primitive idyll. He was unable to afford the pleasure-seeking life-style in Papeete, and an early attempt at a portrait, Suzanne Bambridge, was not well liked.[86] He decided to set up his studio in Mataiea, Papeari, some 45 kilometres (28 mi) from Papeete, installing himself in a native-style bamboo hut. Here he executed paintings depicting Tahitian life such as Fatata te Miti (By the Sea) and Ia Orana Maria (Ave Maria), the latter to become his most prized Tahitian painting.[87]

Many of his finest paintings date from this period. His first portrait of a Tahitian model is thought to be Vahine no te tiare (Woman with a Flower). The painting is notable for the care with which it delineates Polynesian features. He sent the painting to his patron George-Daniel de Monfreid, a friend of Schuffenecker, who was to become Gauguin's devoted champion in Tahiti. By late summer 1892 this painting was being displayed at Goupil's gallery in Paris.[88] Art historian Nancy Mowll Mathews believes that Gauguin's encounter with exotic sensuality in Tahiti, so evident in the painting, was by far the most important aspect of his sojourn there.[89]

Gauguin was lent copies of Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout's 1837 Voyage aux îles du Grand Océan and Edmond de Bovis' 1855 État de la société tahitienne à l'arrivée des Européens, containing full accounts of Tahiti's forgotten culture and religion. Gauguin was fascinated by the accounts of Arioi society and their god 'Oro. Because these accounts contained no illustrations and the Tahitian models had in any case long disappeared, he could give free rein to his imagination. He executed some twenty paintings and a dozen woodcarvings over the next year. The first of these was Te aa no areois (The Seed of the Areoi), representing Oro's terrestrial wife Vairaumati, now held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His illustrated notebook of the time, Ancien Culte Mahorie, is preserved in the Louvre and was published in facsimile form in 1951.[90][91][92]

In all, Gauguin sent nine of his paintings to Monfreid in Paris. These were eventually exhibited in Copenhagen in a joint exhibition with the late Vincent van Gogh. Reports that they had been well received (though in fact only two of the Tahitian paintings were sold and his earlier paintings were unfavourably compared with van Gogh's) were sufficiently encouraging for Gauguin to contemplate returning with some seventy others he had completed.[93][94] He had in any case largely run out of funds, depending on a state grant for a free passage home. In addition he had some health problems diagnosed as heart problems by the local doctor, which Mathews suggests may have been the early signs of cardiovascular syphilis.[95]

Gauguin later wrote a travelogue (first published 1901) titled Noa Noa, originally conceived as commentary on his paintings and describing his experiences in Tahiti. Modern critics have suggested that the contents of the book were in part fantasized and plagiarized.[96][97] In it he revealed that he had at this time taken a 13-year-old girl as native wife or vahine (the Tahitian word for "woman"), a marriage contracted in the course of a single afternoon. This was Teha'amana, called Tehura in the travelogue, who was pregnant by him by the end of summer 1892.[98][99][100][101] Teha'amana was the subject of several of Gauguin's paintings, including Merahi metua no Tehamana and the celebrated Spirit of the Dead Watching, as well as a notable woodcarving Tehura now in the Musée d'Orsay.[102] By the end of July 1893, Gauguin had decided to leave Tahiti and he would never see Teha'amana or her child again even after returning to the island several years later.[103] A digital catalogue raisonné of the paintings from this period was released by the Wildenstein Plattner Institute in 2021.[104]

Page from Gauguin's notebook (date unknown), Ancien Culte Mahorie. Louvre

Page from Gauguin's notebook (date unknown), Ancien Culte Mahorie. Louvre Te aa no areois (The Seed of the Areoi), 1892, Museum of Modern Art

Te aa no areois (The Seed of the Areoi), 1892, Museum of Modern Art.JPG.webp)

%252C_polychromed_pua_wood%252C_H._22.2_cm._Realized_during_Gauguin's_first_voyage_to_Tahiti._Mus%C3%A9e_d'Orsay%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Tehura (Teha'amana), 1891–3, polychromed pua wood, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Tehura (Teha'amana), 1891–3, polychromed pua wood, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Return to France

%252C_partially_glazed_stoneware%252C_75_x_19_x_27_cm%252C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Orsay.jpg.webp)

In August 1893, Gauguin returned to France, where he continued to execute paintings on Tahitian subjects such as Mahana no atua (Day of the God) and Nave nave moe (Sacred spring, sweet dreams).[107][103] An exhibition at the Durand-Ruel gallery in November 1894 was a moderate success, selling at quite elevated prices 11 of the 40 paintings exhibited. He set up an apartment at 6 rue Vercingétorix, on the edge of the Montparnasse district frequented by artists, and began to conduct a weekly salon. He affected an exotic persona, dressing in Polynesian costume, and conducted a public affair with a young woman still in her teens, "half Indian, half Malayan", known as Annah the Javanese.[108][109]

Despite the moderate success of his November exhibition, he subsequently lost Durand-Ruel's patronage in circumstances that are not clear. Mathews characterises this as a tragedy for Gauguin's career. Amongst other things he lost the chance of an introduction to the American market.[110] The start of 1894 found him preparing woodcuts using an experimental technique for his proposed travelogue Noa Noa. He returned to Pont-Aven for the summer. In February 1895 he attempted an auction of his paintings at Hôtel Drouot in Paris, similar to the one of 1891, but this was not a success. The dealer Ambroise Vollard, however, showed his paintings at his gallery in March 1895, but they unfortunately did not come to terms at that date.[111]

He submitted a large ceramic sculpture he called Oviri he had fired the previous winter to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts 1895 salon opening in April.[105] There are conflicting versions of how it was received: his biographer and Noa Noa collaborator, the Symbolist poet Charles Morice, contended (1920) that the work was "literally expelled" from the exhibition, while Vollard said (1937) that the work was admitted only when Chaplet threatened to withdraw all his own work.[112] In any case, Gauguin took the opportunity to increase his public exposure by writing an outraged letter on the state of modern ceramics to Le Soir.[113]

By this time it had become clear that he and his wife Mette were irrevocably separated. Although there had been hopes of a reconciliation, they had quickly quarrelled over money matters and neither visited the other. Gauguin initially refused to share any part of a 13,000-franc inheritance from his uncle Isidore which he had come into shortly after returning. Mette was eventually gifted 1,500 francs, but she was outraged and from that point on kept in contact with him only through Schuffenecker—doubly galling for Gauguin, as his friend thus knew the true extent of his betrayal.[114][36]

By mid 1895 attempts to raise funds for Gauguin's return to Tahiti had failed, and he began accepting charity from friends. In June 1895 Eugène Carrière arranged a cheap passage back to Tahiti, and Gauguin never saw Europe again.[115]

.jpg.webp) Nave nave moe (Sacred spring, sweet dreams), 1894, Hermitage Museum

Nave nave moe (Sacred spring, sweet dreams), 1894, Hermitage Museum Annah the Javanese, (1893), Private collection[116]

Annah the Javanese, (1893), Private collection[116] Paul Gauguin, Alfons Mucha, Luděk Marold, and Annah the Javanese at Mucha's studio, 1893

Paul Gauguin, Alfons Mucha, Luděk Marold, and Annah the Javanese at Mucha's studio, 1893 Nave Nave Fenua (Delightful Land), woodcut in Noa Noa series, 1894, Art Gallery of Ontario

Nave Nave Fenua (Delightful Land), woodcut in Noa Noa series, 1894, Art Gallery of Ontario

Residence in Tahiti

Gauguin set out for Tahiti again on 28 June 1895. His return is characterised by Thomson as an essentially negative one, his disillusionment with the Paris art scene compounded by two attacks on him in the same issue of Mercure de France;[118][119] one by Emile Bernard, the other by Camille Mauclair. Mathews remarks that his isolation in Paris had become so bitter that he had no choice but to try to reclaim his place in Tahiti society.[120][121]

He arrived in September 1895 and was to spend the next six years living, for the most part, an apparently comfortable life as an artist-colon near, or at times in, Papeete. During this time he was able to support himself with an increasingly steady stream of sales and the support of friends and well-wishers, though there was a period of time 1898–1899 when he felt compelled to take a desk job in Papeete, of which there is not much record. He built a spacious reed and thatch house at Puna'auia in an affluent area ten miles east of Papeete, settled by wealthy families, in which he installed a large studio, sparing no expense. Jules Agostini, an acquaintance of Gauguin's and an accomplished amateur photographer, photographed the house in 1896.[122][123][124] Later a sale of land obliged him to build a new one in the same neighbourhood.[125][126]

He maintained a horse and trap, so was in a position to travel daily to Papeete to participate in the social life of the colony should he wish. He subscribed to the Mercure de France (indeed was a shareholder), by then France's foremost critical journal, and kept up an active correspondence with fellow artists, dealers, critics, and patrons in Paris.[127] During his year in Papeete and thereafter, he played an increasing role in local politics, contributing abrasively to a local journal opposed to the colonial government, Les Guêpes (The Wasps), that had recently been formed, and eventually edited his own monthly publication Le Sourire: Journal sérieux (The Smile: A Serious Newspaper), later titled simply Journal méchant (A Wicked Newspaper).[128] A certain amount of artwork and woodcuts from his newspaper survive.[129] In February 1900 he became the editor of Les Guêpes itself, for which he drew a salary, and he continued as editor until he left Tahiti in September 1901. The paper under his editorship was noted for its scurrilous attacks on the governor and officialdom in general, but was not in fact a champion of native causes, although perceived as such nevertheless.[130][131]

For the first year at least he produced no paintings, informing Monfreid that he proposed henceforth to concentrate on sculpture. Few of his wooden carvings from this period survive, most of them collected by Monfreid. Thomson cites Oyez Hui Iesu (Christ on the Cross), a wooden cylinder half a metre (20") tall featuring a curious hybrid of religious motifs. The cylinder may have been inspired by similar symbolic carvings in Brittany, such as at Pleumeur-Bodou, where ancient menhirs have been Christianised by local craftsmen.[132] When he resumed painting, it was to continue his long-standing series of sexually charged nudes in paintings such as Te tamari no atua (Son of God) and O Taiti (Nevermore). Thomson observes a progression in complexity.[133] Mathews notes a return to Christian symbolism that would have endeared him to the colonists of the time, now anxious to preserve what was left of native culture by stressing the universality of religious principles. In these paintings, Gauguin was addressing an audience amongst his fellow colonists in Papeete, not his former avant-garde audience in Paris.[134][135]

His health took a decided turn for the worse and he was hospitalised several times for a variety of ailments. While he was in France, he had his ankle shattered in a drunken brawl on a seaside visit to Concarneau.[136] The injury, an open fracture, never healed properly. Then painful and debilitating sores that restricted his movement began erupting up and down his legs. These were treated with arsenic. Gauguin blamed the tropical climate and described the sores as "eczema", but his biographers agree this must have been the progress of syphilis.[95][137][lower-alpha 2]

In April 1897, he received word that his favorite daughter Aline had died from pneumonia. This was also the month he learned he had to vacate his house because its land had been sold. He took out a bank loan to build a much more extravagant wooden house with beautiful views of the mountains and sea. But he overextended himself in so doing, and by the end of the year faced the real prospect of his bank foreclosing on him.[139] Failing health and pressing debts brought him to the brink of despair. At the end of the year he completed his monumental Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, which he regarded as his masterpiece and final artistic testament (in a letter to Monfreid he explained that he tried to kill himself after finishing it).[140][141][142] The painting was exhibited at Vollard's gallery in November the following year, along with eight thematically related paintings he had completed by July.[143] This was his first major exhibition in Paris since his Durand-Ruel show in 1893 and it was a decided success, critics praising his new serenity. Where do we come from?, however, received mixed reviews and Vollard had difficulty selling it. He eventually sold it in 1901 for 2,500 francs (about $10,000 in year 2000 US dollars) to Gabriel Frizeau, of which Vollard's commission was perhaps as much as 500 francs.

Georges Chaudet, Gauguin's Paris dealer, died in the fall of 1899. Vollard had been buying Gauguin's paintings through Chaudet and now made an agreement with Gauguin directly.[144][145] The agreement provided Gauguin a regular monthly advance of 300 francs against a guaranteed purchase of at least 25 unseen paintings a year at 200 francs each, and in addition Vollard undertook to provide him with his art materials. There were some initial problems on both sides, but Gauguin was finally able to realise his long cherished plan of resettling in the Marquesas Islands in search of a yet more primitive society. He spent his final months in Tahiti living in considerable comfort, as attested by the liberality with which he entertained his friends at that time.[146][147][148]

Gauguin was unable to continue his work in ceramics in the islands for the simple reason that suitable clay was not available.[149] Similarly, without access to a printing press (Le Sourire was hectographed),[150] he was obliged to turn to the monotype process in his graphic work.[151] Surviving examples of these prints are rather rare and command very high prices in the saleroom.[152]

During this time Gauguin maintained a relationship with Pahura (Pau'ura) a Tai, the daughter of neighbours in Puna'auia. Gauguin began this relationship when Pau'ura was 14+1⁄2 years old.[153] He fathered two children with her, of which a daughter died in infancy. The other, a boy, she raised herself. His descendants still inhabited Tahiti at the time of Mathews' biography. Pahura refused to accompany Gauguin to the Marquesas away from her family in Puna'auia (earlier she had left him when he took work in Papeete just 10 miles away).[154] When the English writer Willam Somerset Maugham visited her in 1917, she could offer him no useful memory of Gauguin and chided him for visiting her without bringing money from Gauguin's family.[155]

.jpg.webp) Oyez Hui Iesu (Christ on the Cross), rubbing (reverse print) from an 1896 wooden cylinder, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Oyez Hui Iesu (Christ on the Cross), rubbing (reverse print) from an 1896 wooden cylinder, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

%252C_1899%E2%80%931900_monotype.jpg.webp) Eve (The Nightmare), 1899–1900, monotype, J. Paul Getty Museum

Eve (The Nightmare), 1899–1900, monotype, J. Paul Getty Museum

Marquesas Islands

.JPG.webp)

Gauguin had nurtured his plan of settling in the Marquesas ever since seeing a collection of intricately carved Marquesan bowls and weapons in Papeete during his first months in Tahiti.[156] However, he found a society that, as in Tahiti, had lost its cultural identity. Of all the Pacific island groups, the Marquesas were the most affected by the import of Western diseases (especially tuberculosis).[157] An 18th-century population of some 80,000 had declined to just 4,000.[158] Catholic missionaries held sway and, in their effort to control drunkenness and promiscuity, obliged all native children to attend missionary schools into their teens. French colonial rule was enforced by a gendarmerie noted for its malevolence and stupidity, while traders, both Western and Chinese, exploited the natives appallingly.[159][160]

Gauguin settled in Atuona on the island of Hiva-Oa, arriving 16 September 1901.[lower-alpha 3] This was the administrative capital of the island group, but considerably less developed than Papeete although there was an efficient and regular steamer service between the two. There was a military doctor but no hospital. The doctor was relocated to Papeete the following February and thereafter Gauguin had to rely on the island's two health care workers, the Vietnamese exile Nguyen Van Cam (Ky Dong), who had settled on the island but had no formal medical training, and the Protestant pastor Paul Vernier, who had studied medicine in addition to theology.[161][162] Both of these were to become close friends.[163]

He bought a plot of land in the center of the town from the Catholic mission, having first ingratiated himself with the local bishop by attending mass regularly. This bishop was Monseigneur Joseph Martin, initially well disposed to Gauguin because he was aware that Gauguin had sided with the Catholic party in Tahiti in his journalism.[164]

Gauguin built a two-floor house on his plot, sturdy enough to survive a later cyclone which washed away most other dwellings in the town. He was helped in the task by the two best Marquesan carpenters on the island, one of them called Tioka, tattooed from head to toe in the traditional Marquesan way (a tradition suppressed by the missionaries). Tioka was a deacon in Vernier's congregation and became Gauguin's neighbour after the cyclone when Gauguin gifted him a corner of his plot. The ground floor was open-air and used for dining and living, while the top floor was used for sleeping and as his studio. The door to the top floor was decorated with a polychrome wood-carved lintel and jambs that still survive in museums. The lintel named the house as Maison du Jouir (i.e. House of Pleasure), while the jambs echoed his earlier 1889 wood-carving Soyez amoureuses vous serez heureuses (i.e. Be in Love, You Will Be Happy). The walls were decorated with, amongst other things, his prized collection of forty-five pornographic photographs he had purchased in Port Said on his way out from France.[165]

In the early days at least, until Gauguin found a vahine, the house drew appreciative crowds in the evenings from the natives, who came to stare at the pictures and party half the night away.[166] Needless to say, all this did not endear Gauguin to the bishop, still less when Gauguin erected two sculptures he placed at the foot of his steps lampooning the bishop and a servant reputed to be the bishop's mistress,[167] and yet still less when Gauguin later attacked the unpopular missionary school system.[168] The sculpture of the bishop, Père Paillard, is to be found at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, while its pendant piece Thérèse realized a record $30,965,000 for a Gauguin sculpture at a Christie's New York 2015 sale.[169][170] These were among at least eight sculptures that adorned the house according to a posthumous inventory, most of which are lost today. Together they represented a very public attack on the hypocrisy of the church in sexual matters.[171][172]

State funding for the missionary schools had ceased as a result of the 1901 Associations Bill promulgated throughout the French empire.[157][164][173] The schools continued with difficulty as private institutions, but these difficulties were compounded when Gauguin established that attendance at any given school was only compulsory within a catchment area of some two and a half miles radius. This led to numerous teenage daughters being withdrawn from the schools (Gauguin called this process "rescuing"). He took as vahine one such girl, Vaeoho (also called Marie-Rose), the 14-year-old daughter of a native couple who lived in an adjoining valley six miles distant.[174] This can scarcely have been a pleasant task for her as Gauguin's sores were by then extremely noxious and required daily dressing.[162] Nevertheless, she lived willingly with him and the following year gave birth to a healthy daughter whose descendants continue to live on the island.[175][176]

By November he had settled into his new home with Vaeoho, a cook (Kahui), two other servants (nephews of Tioka), his dog, Pegau (a play on his initials PG), and a cat. The house itself, although in the center of the town, was set amongst trees and secluded from view. The partying ceased and he began a period of productive work, sending twenty canvases to Vollard the following April.[177] He had thought he would find new motifs in the Marquesas, writing to Monfreid:[178][179]

I think in the Marquesas, where it is easy to find models (a thing that is growing more and more difficult in Tahiti), and with new country to explore – with new and more savage subject matter in brief – that I shall do beautiful things. Here my imagination has begun to cool, and then, too, the public has grown so used to Tahiti. The world is so stupid that if one shows it canvases containing new and terrible elements, Tahiti will become comprehensible and charming. My Brittany pictures are now rose-water because of Tahiti; Tahiti will become eau de Cologne because of the Marquesas.

— Paul Gauguin, Letter LII to George Daniel de Monfreid, June 1901

In fact, his Marquesas work for the most part can only be distinguished from his Tahiti work by experts or by their dates,[180] paintings such as Two Women remaining uncertain in their location.[181] For Anna Szech, what distinguishes them is their repose and melancholy, albeit containing elements of disquiet. Thus, in the second of two versions of Cavaliers sur la Plage (Riders on the Beach), gathering clouds and foamy breakers suggest an impending storm while the two distant figures on grey horses echo similar figures in other paintings that are taken to symbolise death.[178]

Gauguin chose to paint landscapes, still lifes, and figure studies at this time, with an eye to Vollard's clientele, avoiding the primitive and lost paradise themes of his Tahiti paintings.[182] But there is a significant trio of pictures from this last period that suggest deeper concerns. The first two of these are Jeune fille à l'éventail (Young Girl with Fan) and Le Sorcier d'Hiva Oa (Marquesan Man in a Red Cape). The model for Jeune fille was the red-headed Tohotaua, the daughter of a chieftain on a neighbouring island. The portrait appears to have been taken from a photograph that Vernier later sent to Vollard. The model for Le sorcier may have been Haapuani, an accomplished dancer as well as a feared magician, who was a close friend of Gauguin's and, according to Bengt Danielsson, married to Tohotau.[183] Szech notes that the white colour of Tohotau's dress is a symbol of power and death in Polynesian culture, the sitter doing duty for a Maohi culture as a whole threatened with extinction.[178] Le Sorcier appears to have been executed at the same time and depicts a long-haired young man wearing an exotic red cape. The androgynous nature of the image has attracted critical attention, giving rise to speculation that Gauguin intended to depict a māhū (i.e. a third gender person) rather than a taua or priest.[180][184][185] The third picture of the trio is the mysterious and beautiful Contes barbares (Primitive Tales) featuring Tohotau again at the right. The left figure is Jacob Meyer de Haan, a painter friend of Gauguin's from their Pont-Aven days who had died a few years previously, while the middle figure is again androgynous, identified by some as Haapuani. The Buddha-like pose and the lotus blossoms suggests to Elizabeth Childs that the picture is a meditation on the perpetual cycle of life and the possibility of rebirth.[182] As these paintings reached Vollard after Gauguin's sudden death, nothing is known about Gauguin's intentions in their execution.[186]

In March 1902, the governor of French Polynesia, Édouard Petit, arrived in the Marquesas to make an inspection. He was accompanied by Édouard Charlier as head of the judicial system. Charlier was an amateur painter who had been befriended by Gauguin when he first arrived as magistrate at Papeete in 1895.[187] However their relationship had turned to enmity when Charlier refused to prosecute Gauguin's then vahine Pau'ura for a number of trivial offences, allegedly housebreaking and theft, she had committed at Puna'auia while Gauguin was away working in Papeete. Gauguin had gone so far as to publish an open letter attacking Charlier about the affair in Les Guêpes.[188][189][190] Petit, presumably suitably forewarned, refused to see Gauguin to deliver the settlers' protests (Gauguin their spokesman) about the invidious taxation system, which saw most revenue from the Marquesas spent in Papeete. Gauguin responded in April by refusing to pay his taxes and encouraging the settlers, traders and planters, to do likewise.[191]

At around the same time, Gauguin's health began to deteriorate again, revisited by the same familiar constellation of symptoms involving pain in the legs, heart palpitations, and general debility. The pain in his injured ankle grew insupportable and in July he was obliged to order a trap from Papeete so that he could get about town.[161] By September the pain was so extreme that he resorted to morphine injections. However he was sufficiently concerned by the habit he was developing to turn his syringe set over to a neighbour, relying instead on laudanum. His sight was also beginning to fail him, as attested by the spectacles he wears in his last known self-portrait. This was actually a portrait commenced by his friend Ky Dong that he completed himself, thus accounting for its uncharacteristic style.[192] It shows a man tired and aged, yet not entirely defeated.[193] For a while he considered returning to Europe, to Spain, to get treatment. Monfreid advised him:[194][195]

In returning you will risk damaging that process of incubation which is taking place in the public's appreciation of you. At present you are a unique and legendary artist, sending to us from the remote South Seas disconcerting and inimitable works which are the definitive creations of a great man who, in a way, has already gone from this world. Your enemies – and like all who upset the mediocrities you have many enemies – are silent; but they dare not attack you, do not even think of it. You are so far away. You should not return... You are already as unassailable as all the great dead; you already belong to the history of art.

— George Daniel Monfreid, Letter to Paul Gauguin circa October 1902

In July 1902, Vaeoho, by then seven months pregnant, left Gauguin to return home to her neighbouring valley of Hekeani to have her baby amongst family and friends. She gave birth in September but did not return. Gauguin did not subsequently take another vahine. It was at this time that his quarrel with Bishop Martin over missionary schools reached its height. The local gendarme, Désiré Charpillet, at first friendly to Gauguin, wrote a report to the administrator of the island group, who resided on the neighbouring island of Nuku Hiva, criticizing Gauguin for encouraging natives to withdraw their children from school as well as encouraging settlers to withhold payment of their taxes. As luck would have it, the post of administrator had recently been filled by François Picquenot, an old friend of Gauguin's from Tahiti and essentially sympathetic to him. Picquenot advised Charpillet not to take any action over the schools issue, since Gauguin had the law on his side, but authorised Charpillet to seize goods from Gauguin in lieu of payment of taxes if all else failed.[196] Possibly prompted by loneliness, and at times unable to paint, Gauguin took to writing.[197][198]

In 1901, the manuscript of Noa Noa that Gauguin had prepared along with woodcuts during his interlude in France was finally published with Morice's poems in book form in the La Plume edition (the manuscript itself is now lodged in the Louvre museum). Sections of it (including his account of Teha'amana) had previously been published without woodcuts in 1897 in La Revue Blanche, while he himself had published extracts in Les Guêpes while he was editor. The La Plume edition was planned to include his woodcuts, but he withheld permission to print them on smooth paper as the publishers wished.[199] In truth he had grown uninterested in the venture with Morice and never saw a copy, declining an offer of one hundred complimentary copies.[200] Nevertheless, its publication inspired him to consider writing other books.[201] At the beginning of the year (1902), he had revised an old 1896–97 manuscript, L'Esprit Moderne et le Catholicisme (The Modern Spirit and Catholicism), on the Roman Catholic Church, adding some twenty pages containing insights gleaned from his dealings with Bishop Martin. He sent this text to Bishop Martin, who responded by sending him an illustrated history of the Church. Gauguin returned the book with critical remarks he later published in his autobiographical reminisces.[202][203] He next prepared a witty and well-documented essay, Racontars de Rapin (Tales of a Dabbler) on critics and art criticism, which he sent for publication to André Fontainas, art critic at the Mercure de France whose favourable review of Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? had done much to restore his reputation. Fontainas, however, replied that he dared not publish it. It was not subsequently published until 1951.[201][204][205][206][207]

On 27 May that year, the steamer service, Croix du Sud, was shipwrecked off the Apataki atoll, and for a period of three months the island was left without mail or supplies.[208][209] When mail service resumed, Gauguin penned an angry attack on Governor Petit in an open letter, complaining amongst other things about the way they had been abandoned following the shipwreck. The letter was published by L'Indepéndant, the successor newspaper to Les Guêpes, that November in Papeete. Petit had in fact followed an independent and pro-native policy, to the disappointment of the Roman Catholic Party, and the newspaper was preparing an attack on him. Gauguin also sent the letter to the Mercure de France, which published a redacted version of it after his death.[204] He followed this with a private letter to the head of the gendarmerie in Papeete, complaining about his own local gendarme Charpillet's excesses in making prisoners labor for him. Danielsson notes that, while these and similar complaints were well-founded, the motivation for them all was wounded vanity and simple animosity. As it happened, the relatively supportive Charpillet was replaced that December by another gendarme, Jean-Paul Claverie, from Tahiti, much less well disposed to Gauguin and who in fact had fined him in his earliest Mataiea days for public indecency, having caught him bathing naked in a local stream following complaints from the missionaries there.[210]

His health further deteriorated in December to the extent that he was scarcely able to paint. He began an autobiographical memoir he called Avant et après (Before and After) (published in translation in the US as Intimate Journals), which he completed over the next two months.[68] The title was supposed to reflect his experiences before and after coming to Tahiti and as tribute to his own grandmother's unpublished memoir Past and Future. His memoir proved to be a fragmented collection of observations about life in Polynesia, his own life, and comments on literature and paintings. He included in it attacks on subjects as diverse as the local gendarmerie, Bishop Martin, his wife Mette and the Danes in general, and concluded with a description of his personal philosophy conceiving life as an existential struggle to reconcile opposing binaries.[211][lower-alpha 4] Mathews notes two closing remarks as a distillation of his philosophy:

No one is good; no one is evil; everyone is both, in the same way and in different ways. …

It is so small a thing, the life of a man, and yet there is time to do great things, fragments of the common task.— Paul Gauguin, Intimate Journals, 1903[214]

He sent the manuscript to Fontainas for editing, but the rights reverted to Mette after Gauguin's death, and it was not published until 1918 (in a facsimile edition); the American translation appearing in 1921.[215]

Death

At the beginning of 1903, Gauguin engaged in a campaign designed to expose the incompetence of the island's gendarmes, in particular Jean-Paul Claverie, for taking the side of the natives directly in a case involving the alleged drunkenness of a group of them.[216] Claverie, however, escaped censure. At the beginning of February, Gauguin wrote to the administrator, François Picquenot, alleging corruption by one of Claverie's subordinates. Picquenot investigated the allegations but could not substantiate them. Claverie responded by filing a charge against Gauguin of libeling a gendarme. He was subsequently fined 500 francs and sentenced to three months' imprisonment by the local magistrate on 27 March 1903. Gauguin immediately filed an appeal in Papeete and set about raising the funds to travel to Papeete to hear his appeal.[217]

At this time Gauguin was very weak and in great pain and resorted once again to using morphine. He died suddenly on the morning of 8 May 1903. [218][219][lower-alpha 5]

![Cavaliers sur la Plage [II] (Riders on the Beach), 1902, Private collection](../I/Paul_Gauguin_106.jpg.webp) Cavaliers sur la Plage [II] (Riders on the Beach), 1902, Private collection

Cavaliers sur la Plage [II] (Riders on the Beach), 1902, Private collection_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Landscape with a Pig and a Horse (Hiva Oa), 1903, Ateneum, Helsinki

Landscape with a Pig and a Horse (Hiva Oa), 1903, Ateneum, Helsinki Still life with Exotic Birds, 1902, Pushkin Museum

Still life with Exotic Birds, 1902, Pushkin Museum Jeune fille à l'éventail (Young Girl with a Fan), 1902, Museum Folkwang

Jeune fille à l'éventail (Young Girl with a Fan), 1902, Museum Folkwang Contes barbares (Primitive Tales), 1902, Museum Folkwang

Contes barbares (Primitive Tales), 1902, Museum Folkwang

Earlier, he had sent for his pastor, Paul Vernier, complaining of fainting fits. They had chatted together, and Vernier had left, believing him in a stable condition. However, Gauguin's neighbour, Tioka, found him dead at 11 o'clock, confirming the fact in the traditional Marquesan way by chewing his head in an attempt to revive him. By his bedside was an empty bottle of laudanum, which has given rise to speculation that he was the victim of an overdose.[220][221] Vernier believed he died of a heart attack.[222]

Gauguin was buried in the Catholic Calvary Cemetery (Cimetière Calvaire), Atuona, Hiva 'Oa, at 2 p.m. the next day. In 1973, a bronze cast of his Oviri figure was placed on his grave, as he had indicated was his wish.[223] Ironically, his nearest neighbor in the cemetery is Bishop Martin, his grave surmounted by a large white cross. Vernier wrote an account of Gauguin's last days and burial, reproduced in O'Brien's edition of Gauguin's letters to Monfreid.[224]

Word of Gauguin's death did not reach France (to Monfreid) until 23 August 1903. In the absence of a will, his less valuable effects were auctioned in Atuona while his letters, manuscripts, and paintings were auctioned in Papeete on 5 September 1903. Mathews notes that this speedy dispersal of his effects led to the loss of much valuable information about his later years. Thomson notes that the auction inventory of his effects (some of which were burned as pornography) revealed a life that was not as impoverished or primitive as he had liked to maintain.[225] Mette Gauguin in due course received the proceeds of the auction, some 4,000 francs.[226] One of the paintings auctioned in Papeete was Maternité II, a smaller version of Maternité I in the Hermitage Museum. The original was painted at the time his then vahine, Pau'ura, in Puna'auia, gave birth to their son Emile. It is not known why he painted the smaller copy. It was sold for 150 francs to a French naval officer, Commandant Cochin, who said that Governor Petit himself had bid up to 135 francs for the painting. It was sold at Sotheby's for US$39,208,000 in 2004.[227]

The Paul Gauguin Cultural Center at Atuona has a reconstruction of the Maison du Jouir. The original house stood empty for a few years, the door still carrying Gauguin's carved lintel. This was eventually recovered, four of the five pieces held at the Musée D'Orsay and the fifth at the Paul Gauguin Museum in Tahiti.[228]

In 2014, forensic examination of four teeth found in a glass jar in a well near Gauguin's house threw into question the conventional belief that Gauguin had suffered from syphilis. DNA examination established that the teeth were almost certainly Gauguin's, but no traces were found of the mercury that was used to treat syphilis at the time, suggesting either that Gauguin did not suffer from syphilis or that he was not being treated for it.[229][230] In 2007, four rotten molars, which may have been Gauguin's, were found by archaeologists at the bottom of a well that he built on the island of Hiva Oa, on the Marquese Islands.[231]

Children

Gauguin outlived three of his children; his favorite daughter Aline died of pneumonia, his son Clovis died of a blood infection following a hip operation,[232] and a daughter, whose birth was portrayed in Gauguin's painting of 1896 Te tamari no atua, the child of Gauguin's young Tahitian mistress, Pau'ura, died only a few days after her birth on Christmas Day 1896.[233] His son, Émile Gauguin, worked as a construction engineer in the U.S. and is buried in Lemon Bay Historical Cemetery, in Florida. Another son, Jean René, became a well-known sculptor and a staunch socialist. He died on 21 April 1961 in Copenhagen. Pola (Paul Rollon) became an artist and art critic and wrote a memoir, My Father, Paul Gauguin (1937). Gauguin had several other children by his mistresses: Germaine (born 1891) with Juliette Huais (1866–1955); Émile Marae a Tai (born 1899) with Pau'ura; and a daughter (born 1902) with Vaeoho (Marie-Rose). There is some speculation that the Belgian artist, Germaine Chardon, was Gauguin's daughter. Emile Marae a Tai, illiterate and raised in Tahiti by Pau'ura, was brought to Chicago in 1963 by the French journalist Josette Giraud and was an artist in his own right, his descendants still living in Tahiti as of 2001.[232][234]

Historical significance

Primitivism was an art movement of late 19th-century painting and sculpture, characterized by exaggerated body proportions, animal totems, geometric designs, and stark contrasts. The first artist to systematically use these effects and achieve broad public success was Paul Gauguin.[235] The European cultural elite, discovering the art of Africa, Micronesia, and Native Americans for the first time, were fascinated, intrigued, and educated by the newness, wildness, and the stark power embodied in the art of those faraway places. Like Pablo Picasso in the early days of the 20th century, Gauguin was inspired and motivated by the raw power and simplicity of the so-called Primitive Art of those foreign cultures.[236]

Gauguin is also considered a Post-Impressionist painter. His bold, colourful, and design oriented paintings significantly influenced Modern art. Artists and movements in the early 20th century inspired by him include Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, André Derain, Fauvism, Cubism, and Orphism, among others. Later, he influenced Arthur Frank Mathews and the American Arts and Crafts movement.

John Rewald, recognized as a foremost authority on late 19th-century art, wrote a series of books about the Post-Impressionist period, including Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin (1956) and an essay, Paul Gauguin: Letters to Ambroise Vollard and André Fontainas (included in Rewald's Studies in Post-Impressionism, 1986), discusses Gauguin's years in Tahiti and the struggles of his survival as seen through correspondence with the art dealer Vollard and others.[237]

Influence on Picasso

Gauguin's posthumous retrospective exhibitions at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1903, and an even larger one in 1906, had a stunning and powerful influence on the French avant-garde and in particular Pablo Picasso's paintings. In the autumn of 1906, Picasso made paintings of oversized nude women and monumental sculptural figures that recalled the work of Paul Gauguin and showed his interest in primitive art. Picasso's paintings of massive figures from 1906 were directly influenced by Gauguin's sculpture, painting, and his writing as well. The power evoked by Gauguin's work led directly to Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in 1907.[238]

According to Gauguin biographer, David Sweetman, Picasso, as early as 1902, became a fan of Gauguin's work when he met and befriended the expatriate Spanish sculptor and ceramist Paco Durrio, in Paris. Durrio had several of Gauguin's works on hand because he was a friend of Gauguin's and an unpaid agent of his work. Durrio tried to help his poverty-stricken friend in Tahiti by promoting his oeuvre in Paris. After they met, Durrio introduced Picasso to Gauguin's stoneware, helped Picasso make some ceramic pieces, and gave Picasso a first La Plume edition of Noa Noa: The Tahiti Journal of Paul Gauguin.[239] In addition to seeing Gauguin's work at Durrio's, Picasso also saw the work at Ambroise Vollard's gallery where both he and Gauguin were represented.

Concerning Gauguin's impact on Picasso, John Richardson wrote:

The 1906 exhibition of Gauguin's work left Picasso more than ever in this artist's thrall. Gauguin demonstrated the most disparate types of art—not to speak of elements from metaphysics, ethnology, symbolism, the Bible, classical myths, and much else besides—could be combined into a synthesis that was of its time yet timeless. An artist could also confound conventional notions of beauty, he demonstrated, by harnessing his demons to the dark gods (not necessarily Tahitian ones) and tapping a new source of divine energy. If in later years Picasso played down his debt to Gauguin, there is no doubt that between 1905 and 1907 he felt a very close kinship with this other Paul, who prided himself on Spanish genes inherited from his Peruvian grandmother. Had not Picasso signed himself 'Paul' in Gauguin's honor.[240]

Both David Sweetman and John Richardson point to the Gauguin sculpture called Oviri (literally meaning 'savage'), the gruesome phallic figure of the Tahitian goddess of life and death that was intended for Gauguin's grave, exhibited in the 1906 retrospective exhibition that even more directly led to Les Demoiselles. Sweetman writes, "Gauguin's statue Oviri, which was prominently displayed in 1906, was to stimulate Picasso's interest in both sculpture and ceramics, while the woodcuts would reinforce his interest in print-making, though it was the element of the primitive in all of them which most conditioned the direction that Picasso's art would take. This interest would culminate in the seminal Les Demoiselles d'Avignon."[241]

According to Richardson,

Picasso's interest in stoneware was further stimulated by the examples he saw at the 1906 Gauguin retrospective at the Salon d'Automne. The most disturbing of those ceramics (one that Picasso might have already seen at Vollard's) was the gruesome Oviri. Until 1987, when the Musée d'Orsay acquired this little-known work (exhibited only once since 1906) it had never been recognized as the masterpiece it is, let alone recognized for its relevance to the works leading up to the Demoiselles. Although just under 30 inches high, Oviri has an awesome presence, as befits a monument intended for Gauguin's grave. Picasso was very struck by Oviri. 50 years later he was delighted when [Douglas] Cooper and I told him that we had come upon this sculpture in a collection that also included the original plaster of his cubist head. Has it been a revelation, like Iberian sculpture? Picasso's shrug was grudgingly affirmative. He was always loath to admit Gauguin's role in setting him on the road to Primitivism.[242]

Technique and style

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_73.2_x_91.5_cm%252C_Kunstmuseum_Basel.jpg.webp)

Gauguin's initial artistic guidance was from Pissarro, but the relationship left more of a mark personally than stylistically. Gauguin's masters were Giotto, Raphael, Ingres, Eugène Delacroix, Manet, Degas, and Cézanne.[243][71][77][244][245] His own beliefs, and in some cases the psychology behind his work, were also influenced by philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and poet Stéphane Mallarmé.[246][245]

Gauguin, like some of his contemporaries such as Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, employed a technique for painting on canvas known as peinture à l'essence. For this, the oil (binder) is drained from the paint and the remaining sludge of pigment is mixed with turpentine. He may have used a similar technique in preparing his monotypes, using paper instead of metal, as it would absorb oil giving the final images a matte appearance he desired.[247] He also proofed some of his existing drawings with the aid of glass, copying an underneath image onto the glass surface with watercolour or gouache for printing. Gauguin's woodcuts were no less innovative, even to the avant-garde artists responsible for the woodcut revival happening at that time. Instead of incising his blocks with the intent of making a detailed illustration, Gauguin initially chiseled his blocks in a manner similar to wood sculpture, followed by finer tools to create detail and tonality within his bold contours. Many of his tools and techniques were considered experimental. This methodology and use of space ran parallel to his painting of flat, decorative reliefs.[248]

Starting in Martinique, Gauguin began using analogous colours in close proximity to achieve a muted effect.[249] Shortly after this, he also made his breakthroughs in non-representational colour, creating canvases that had an independent existence and vitality all their own.[250] This gap between surface reality and himself displeased Pissarro and quickly led to the end of their relationship.[251] His human figures at this time are also a reminder of his love affair with Japanese prints, particularly gravitating to the naivety of their figures and compositional austerity as an influence on his primitive manifesto.[249] For that very reason, Gauguin was also inspired by folk art. He sought out a bare emotional purity of his subjects conveyed in a straightforward way, emphasizing major forms and upright lines to clearly define shape and contour.[252] Gauguin also used elaborate formal decoration and colouring in patterns of abstraction, attempting to harmonize man and nature.[253] His depictions of the natives in their natural environment are frequently evident of serenity and a self-contained sustainability.[254] This complemented one of Gauguin's favorite themes, which was the intrusion of the supernatural into day-to-day life, in one instance going so far as to recall ancient Egyptian tomb reliefs with Her Name is Vairaumati and Ta Matete.[255]

In an interview with L'Écho de Paris published on 15 March 1895, Gauguin explains that his developing tactical approach is reaching for synesthesia.[256] He states:

- Every feature in my paintings is carefully considered and calculated in advance. Just as in a musical composition, if you like. My simple object, which I take from daily life or from nature, is merely a pretext, which helps me by the means of a definite arrangement of lines and colours to create symphonies and harmonies. They have no counterparts at all in reality, in the vulgar sense of that word; they do not give direct expression to any idea, their only purpose is to stimulate the imagination—just as music does without the aid of ideas or pictures—simply by that mysterious affinity which exists between certain arrangements of colours and lines and our minds.[257]

In an 1888 letter to Schuffenecker, Gauguin explains the enormous step he had taken away from Impressionism and that he was now intent on capturing the soul of nature, the ancient truths and character of its scenery and inhabitants. Gauguin wrote:

- Don't copy nature too literally. Art is an abstraction. Derive it from nature as you dream in nature's presence, and think more about the act of creation than the outcome.[258]

Other media

Gauguin began making prints in 1889, highlighted by a series of zincographs commissioned by Theo van Gogh known as the Volpini Suite, which also appeared in the Cafe des Arts show of 1889. Gauguin was not hindered by his printing inexperience, and made a number of provocative and unorthodox choices, such as a zinc plate instead of limestone (lithography), wide margins and large sheets of yellow poster paper.[259][260] The result was vivid to the point of garish, but foreshadows his more elaborate experiments with colour printing and intent to elevate monochromatic images. His first masterpieces of printing were from the Noa Noa Suite of 1893–94 where he was one of a number of artists reinventing the technique of the woodcut, bringing it into the modern era. He started the series shortly after returning from Tahiti, eager to reclaim a leadership position within the avant-garde and share pictures based on his French Polynesia excursion. These woodcuts were shown at his unsuccessful 1893 show at Paul Durand-Ruel's, and most were directly related to paintings of his in which he had revised the original composition. They were shown again at a small show in his studio in 1894, where he garnered rare critical praise for his exceptional painterly and sculptural effects. Gauguin's emerging preference for the woodcut was not only a natural extension of his wood reliefs and sculpture, but may have also been provoked by its historical significance to medieval artisans and the Japanese.[261]

%252C_from_the_Noa_Noa_suite%252C_1893%E2%80%9394.jpg.webp)

_-_Paul_Gauguin.jpg.webp)

Gauguin started making watercolour monotypes in 1894, likely overlapping his Noa Noa woodcuts, perhaps even serving as a source of inspiration for them. His techniques remained innovative and it was an apt technique for him as it did not require elaborate equipment, such as a printing press. Despite often being a source of practice for related paintings, sculptures or woodcuts, his monotype innovation offers a distinctly ethereal aesthetic; ghostly afterimages that may express his desire to convey the immemorial truths of nature. His next major woodcut and monotype project was not until 1898–99, known as the Vollard Suite. He completed this enterprising series of 475 prints from some twenty different compositions and sent them to the dealer Ambroise Vollard, despite not compromising to his request for salable, conformed work. Vollard was unsatisfied and made no effort to sell them. Gauguin's series is starkly unified with black and white aesthetic and may have intended the prints to be similar to a set of myriorama cards, in which they may be laid out in any order to create multiple panoramic landscapes.[262] This activity of arranging and rearranging was similar to his own process of repurposing his images and motifs, as well as a symbolism tendency.[263] He printed the work on tissue-thin Japanese paper and the multiple proofs of gray and black could be arranged on top of one another, each transparency of colour showing through to produce a rich, chiaroscuro effect.[264]

In 1899 he started his radical experiment: oil transfer drawings. Much like his watercolour monotype technique, it was a hybrid of drawing and printmaking. The transfers were the grand culmination of his quest for an aesthetic of primordial suggestion, which seems to be relayed in his results that echo ancient rubbings, worn frescos and cave paintings. Gauguin's technical progress from monotyping to the oil transfers is quite noticeable, advancing from small sketches to ambitiously large, highly finished sheets. With these transfers he created depth and texture by printing multiple layers onto the same sheet, beginning with graphite pencil and black ink for delineation, before moving to blue crayon to reinforce line and add shading. He would often complete the image with a wash of oiled-down olive or brown ink. The practice consumed Gauguin until his death, fueling his imagination and conception of new subjects and themes for his paintings. This collection was also sent to Vollard who remained unimpressed. Gauguin prized oil transfers for the way they transformed the quality of drawn line. His process, nearly alchemical in nature, had elements of chance by which unexpected marks and textures regularly arose, something that fascinated him. In metamorphosing a drawing into a print, Gauguin made a calculated decision of relinquishing legibility in order to gain mystery and abstraction.[265][266]

He worked in wood throughout his career, particularly during his most prolific periods, and is known for having achieved radical carving results before doing so with painting. Even in his earliest shows, Gauguin often included wood sculpture in his display, from which he built his reputation as a connoisseur of the so-called primitive. A number of his early carvings appear to be influenced by Gothic and Egyptian art.[267] In correspondence, he also asserts a passion for Cambodian art and the masterful colouring of Persian carpet and Oriental rug.[268]

Legacy