The Louis XIV style or Louis Quatorze (/ˌluːi kæˈtɔːrz, - kəˈ-/ LOO-ee ka-TORZ, - kə-, French: [lwi katɔʁz] ⓘ), also called French classicism, was the style of architecture and decorative arts intended to glorify King Louis XIV and his reign. It featured majesty, harmony and regularity. It became the official style during the reign of Louis XIV (1643–1715), imposed upon artists by the newly established Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) and the Académie royale d'architecture (Royal Academy of Architecture). It had an important influence upon the architecture of other European monarchs, from Frederick the Great of Prussia to Peter the Great of Russia. Major architects of the period included François Mansart, Jules Hardouin Mansart, Robert de Cotte, Pierre Le Muet, Claude Perrault, and Louis Le Vau. Major monuments included the Palace of Versailles, the Grand Trianon at Versailles, and the Church of Les Invalides (1675–1691).

The Louis XIV style had three periods. During the first period, which coincided with the youth of the King (1643–1660) and the regency of Anne of Austria, architecture and art were strongly influenced by the earlier style of Louis XIII and by the Baroque style imported from Italy. The early period saw the beginning of French classicism, particularly in the early works of Francois Mansart, such as the Chateau de Maisons (1630–1651). During the second period (1660–1690), under the personal rule of the King, the style of architecture and decoration became more classical, triumphant and ostentatious, expressed in the building of the Chateau of Versailles, first by Louis Le Vau and then Jules Hardouin-Mansart.[1] Until 1680, furniture was massive, decorated with a profusion of sculpture and gilding. In the later period, thanks to the development of the craft of marquetry, the furniture was decorated with different colors and different woods. The most prominent creator of furniture in the later period was André Charles Boulle.[2] The final period of Louis XIV style, from about 1690 to 1715, is called the period of transition; it was influenced by Hardouin-Mansart and by the King's designer of fetes and ceremonies, Jean Bérain the Elder. The new style was lighter in form, and featured greater fantasy and freedom of line, thanks in part to the use of wrought iron decoration, and greater use of arabesque, grotesque and coquille designs, which continued into the Louis XV style.[3]

Civil architecture

The model of civil architecture in the early part of the reign was Vaux le Vicomte (1658), by Louis Le Vau, built for the King's chief of finance Nicolas Fouquet and completed in 1658. Louis XIV charged Fouquet with theft, put him prison, and took the building for himself. The design was strongly influenced by the classicism of François Mansart. It combined a facade dominated and rhymed by colossal classical columns, beneath a dome, imported from the Italian Baroque architecture, along with a number of original features, such as a semicircular salon which looked out on the vast French formal garden created by André Le Nôtre.[4]

Based on the success of Vaux le Vicomte, Louis XIV selected Le Vau to construct an immense new palace at Versailles, to augment a smaller palace transformed from a hunting lodge by Louis XIII. This gradually became, over the decades, the master work of the Louis XIV style. Following the death of Le Vau in 1680, Jules Hardouin-Mansart took over the Versailles project; he broke away from the picturesque projections and dome and made a more sober and uniform facade of columns, with a flat roof topped by a balustrade and row of columns (1681). He used the same style to harmonize the other new buildings he created at Versailles, including the Orangerie and the Stables. Hardouin-Mansart constructed the Grand Trianon (completed 1687), single-story royal retreat with arched windows alternating with pairs of columns, and a flat roof and balustrade.

Another major new project undertaken by Louis was the construction of a new facade for the east side of the Louvre. In 1665 Louis invited the most famous sculptor architect of the Italian Baroque, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, to submit a design, but in 1667 rejected it in favor of a more sober and classical colonnade, designed by a committee of three, comprising Louis Le Vau, Charles Le Brun, and Claude Perrault.

Vaux le Vicomte by Louis Le Vau (1658)

Vaux le Vicomte by Louis Le Vau (1658)

The Grand Trianon by Jules Hardouin-Mansart (1680–1687)

The Grand Trianon by Jules Hardouin-Mansart (1680–1687) Facade of the Hotel de Soubise by Pierre-Alexis Delamair (1704–1708)

Facade of the Hotel de Soubise by Pierre-Alexis Delamair (1704–1708)

Religious architecture

In the early period of his reign, Louis began building the church of Val-de-Grâce (1645–1710), the chapel of the Val-de-Grace hospital. The design was worked on successively by Mansart, Jacques Lemercier and Pierre Le Muet before being completed by Gabriel Leduc. Its picturesque tripartite facade, peristyle, detached columns, statues, and tondi, make it the most Italianate and Baroque of Paris churches. It served as the prototype for the later domes of Les Invalides and the Pantheon.[5]

The next major church built under Louis XIV was the church of Les Invalides (1680–1706). The nave of the church, by Libéral Bruant, was comparable to those of other churches of the period, with ionic pilasters and penetrating vaults, and an interior that resembled the high baroque style. The dome, by Hardouin-Mansart, was more revolutionary, sitting upon a structure with the plan of a Greek Cross. The design used superimposed orders of columns, in the classical style, but the dome achieved greater height, by resting on a double tambour or drum, and the facade and dome itself were richly decorated with sculptures, entablements in niches, and ornaments of gilded bronze alternating with the nervures, or ribs of the dome.[5]

The finest church interior of the late Louis XIV period is the chapel of the Chateau of Versailles, created between 1697 and 1710 by Hardouin-Mansart and his successor as court architect, Robert de Cotte. The decor was carefully restrained, with light colors and sculptural detail in slight relief on the columns. The interior of the chapel opened up and lightened by the use of classical columns placed on the tribune, one level above the ground floor, to support the weight of the vaulted ceiling.[5]

Church of Val de Grace by Louis Le Vau (1645–1710)

Church of Val de Grace by Louis Le Vau (1645–1710).jpg.webp) Eglise Saint-Roch, Paris, by Jacques Lemercier (1653–1690)

Eglise Saint-Roch, Paris, by Jacques Lemercier (1653–1690) Les Invalides by Hardouin Mansart (1680–1706)

Les Invalides by Hardouin Mansart (1680–1706) Chapel of the Palace of Versailles by Jules Hardouin-Mansart and Robert de Cotte (1689–1710)

Chapel of the Palace of Versailles by Jules Hardouin-Mansart and Robert de Cotte (1689–1710)

The Grand Style: Paris

Though Louis XIV was later accused of having ignored Paris, his reign saw several massive architectural projects which opened up space and ornamented the center of the city. The idea of monumental urban squares surrounded by uniform architecture had begun in Italy, like many architectural ideas of Baroque period. The first such square in Paris was the Place Royal (now Place des Vosges) begun by Henry IV of France, completed later with an equestrian statue of Louis XIII; then the Place Dauphine on the Île de la Cité, which featured, adjacent to it, an equestrian statue of Henry IV. The initial grand Paris projects of Louis XIV were new facades on the Louvre, especially the Colonnade, facing to the east. These were showcases of the new monumental style of Louis XIV. The old brick and stone of the Henry IV squares was replaced by the Grand Style of monumental columns, which usually were part of the facade itself, rather than standing separately. All the buildings around the square were connected and built to the same height, in the same style. The ground floor featured a covered arcade for pedestrians.[6]

The first such complex of buildings built under Louis XIV was the Collège des Quatre-Nations (now the Institut de France) (1662–1668), facing the Louvre. It was designed by Louis Le Vau and François d'Orbay, and combined the new college donated by Mazarin, a chapel, and the library of Cardinal Mazarin. (Later, as the Institute of France, it would become the headquarters of the academies founded by the King.) The Hôtel Royal des Invalides – a complex for war veterans consisting of residences, a hospital, and a chapel – was constructed by Libéral Bruant and Jules Hardouin-Mansart (1671–1679). Louis XIV then commissioned Mansart to construct a separate private royal chapel featuring a striking dome, the Église du Dôme, which was added to complete the complex in 1708.

The next major project was the Place des Victoires (1684–1697), a real estate development of seven large buildings in three segments around a circular square, with a standing figure statue of Louis XIV (later replaced with an equestrian statue) planned for the centerpiece. This was built by an enterprising entrepreneur and nobleman of the court, Jean-Baptiste Prédot, combined with the architect Jules Haroudin-Mansart. The final urban project became the best-known, the Place Vendôme, also by Harouin-Mansart, between 1699 and 1702. Its centerpiece was an equestrian statue of Louis XIV (later replaced with a statue of Napoleon atop the Vendome Column). In another innovation, this project was partially financed by the sale of lots around the square. All of these projects featured monumental facades in the Louis XIV style, giving a particular harmony to the squares.[7]

Place des Victoires (1684–1697) by Jules Hardouin-Mansart

Place des Victoires (1684–1697) by Jules Hardouin-Mansart Place Vendôme (1699–1702) by Jules Hardouin-Mansart

Place Vendôme (1699–1702) by Jules Hardouin-Mansart Court of Honor of Les Invalides (1671–1706)

Court of Honor of Les Invalides (1671–1706)

Interior decoration

In the early Louis XIV style, the principle characteristics of decor were a richness of materials and an effort to achieve a monumental effect. The materials used included marble, often combined with multicolor stones, bronze, paintings, and mirrors. These were inserted into an extremely framework of columns, pilasters, niches, which extended up the walls and up upon the ceiling. The doors were surrounded with medallions, frontons and bas-reliefs. The fireplaces were smaller than those during the Louis XIII era, but more ornate, with a marble shelf supporting vases, below a carved frame with a painting or mirrors, all surrounded by a thick border of carved leaves or flowers.

Decorative elements on the walls of the early Louis XIV style were usually intended to celebrate the military success, majesty and cultural achievements of the King. They often featured military trophies, with helmets, oak leaves symbolizing victory, and masses of weapons, usually made of glided bronze or sculpted wood, in relief surrounded by marble. Other decorative elements celebrated the King personally: the head of the King was often represented as the sun god Apollo, surrounded by palm leaves or gilded rays of light. An eagle usually represented Jupiter. Other ornamental details included gilded numbers, royal batons, and crowns.

The Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles (1678–1684) was the summit of the early Louis XIV style. Designed by Charles Le Brun, it combined a richness of materials (marble, gold, and bronze) which reflected in the mirrors.

In the late Louis XIV period, after 1690, new elements began to appear, that were less militaristic and more fantastic; particularly seashells, surrounded by elaborate sinuous lines and curves; and exotic designs, including arabesques and Chinoiserie.[8]

Early Louis XIV style; the Salon de Vénus at the Palace of Versailles by Charles Le Brun

Early Louis XIV style; the Salon de Vénus at the Palace of Versailles by Charles Le Brun Hall of Mirrors at Palace of Versailles by Charles Le Brun (1678–1684)

Hall of Mirrors at Palace of Versailles by Charles Le Brun (1678–1684) Bedchamber of the Queen, Palace of Versailles

Bedchamber of the Queen, Palace of Versailles

Furniture

During the first period of the reign of Louis XIV, furniture followed the previous style of Louis XIII, and was massive, and profusely decorated with sculpture and gilding. After 1680, thanks in large part to the furniture designer André Charles Boulle, a more original and delicate style appeared, sometimes known as Boulle work. It was based on the inlay of ebony and other rare woods, a technique first used in Florence in the 15th century, which was refined and developed by Boulle and others working for Louis XIV. Furniture was inlaid with plaques of ebony, copper, and exotic woods of different colors.[9]

New and often enduring types of furniture appeared; the commode, with two to four drawers, replaced the old coffre, or chest. The canapé, or sofa, appeared, in the form of a combination of two or three armchairs. New kinds of armchairs appeared, including the fauteuil en confessionale or "confessional armchair", which had padded cushions on either side of the back of the chair. The console table also made its first appearance; it was designed to be placed against a wall. Another new type of furniture was the table à gibier, a marble-topped table for holding dishes. Early varieties of the desk appeared; the Mazarin desk had a central section set back, placed between two columns of drawers, with four feet on each column.[10]

%252C_1708%252C_Grand_Trianon.jpg.webp) Commode by André Charles Boulle for the Grand Trianon (1710)

Commode by André Charles Boulle for the Grand Trianon (1710) Early Mazarin desk

Early Mazarin desk Desk of Nicolas Fouquet at the Chateau of Vaux-le-Vicomte

Desk of Nicolas Fouquet at the Chateau of Vaux-le-Vicomte.jpg.webp) Sofa and chairs à la reine (1710–1720), Louvre Museum

Sofa and chairs à la reine (1710–1720), Louvre Museum

Ceramics

After about 1650, Nevers faience (tin-glazed earthenware), which had long made wares in the Italian maiolica istoriato style, adopted the new French Court style, borrowing from metalwork and other decorative arts, and using prints after the new generation of court painters such as Simon Vouet and Charles Lebrun for the images, which were also painted in many colours. The pieces were often extremely large and ornate, and apart from garden vases and wine-coolers, no doubt decorative rather than practical.[11]

In 1663 Colbert, recently made Louis XIV's finance minister, made a note that the other leading centre of French faience, Rouen faience, should be protected and encouraged, sent designs, and given commissions by the king.[12] Around 1670 the Poterat family of Rouen received part of the large and prestigious commissions for Louis XIV's Trianon de porcelaine, a small palace whose walls were largely covered in painted tiles, in fact of faience rather than porcelain, which was demolished not long after. Nevers and other centres shared these commissions, and others for large fittings and decorations for Louis's other palaces. Nevers garden vases in blue and white were prominently used in the gardens of the Château de Versailles.[13]

The French faience industry received another huge boost when, late in Louis's reign in 1709, the king pressured the wealthy to donate their silver plate, previously what they normally used to dine, to his treasury to help pay for his wars. There was an "overnight frenzy" as the elite rushed to get faience replacements of the best quality.[14]

The reign also saw the earliest French porcelain in Rouen porcelain, although production was on a tiny scale; only nine small pieces are thought to survive.[15] The next factory, Saint-Cloud porcelain, from perhaps 1695 onwards, was more successful,[16] though it was only in the following reign that French porcelain was produced in quantity.

Nevers faience; central dish is 58 cm across, the main scene is the Rape of Europa, after an illustration of Ovid by François Chauveau, published in 1674

Nevers faience; central dish is 58 cm across, the main scene is the Rape of Europa, after an illustration of Ovid by François Chauveau, published in 1674.jpg.webp) Nevers wine-cooler with The Drunkenness of Bacchus, c. 1680

Nevers wine-cooler with The Drunkenness of Bacchus, c. 1680_MET_DT8115_(cropped).jpg.webp) Nevers pair of wine jugs, c. 1685, 56 cm high. François Chauveau's Rape of Europa is again used (left).

Nevers pair of wine jugs, c. 1685, 56 cm high. François Chauveau's Rape of Europa is again used (left)..jpg.webp) Large Nevers ewer with dancing bacchantes and satyrs, 1685

Large Nevers ewer with dancing bacchantes and satyrs, 1685.jpg.webp)

Painting

In the first part of the reign, French painters were largely influenced by the Italians, particularly Caravaggio. Notable French painters included Nicolas Poussin, who was living in Rome; Claude Lorrain, who specialized in landscapes and spent most of his career in Rome; Louis Le Nain, who, along with his brothers, did mostly genre works; Eustache Le Sueur, and Charles Le Brun, who studied with Poussin in Rome and were influenced by him.

With the death in 1661 of Cardinal Mazarin, the King's prime minister, Louis decided to take personal charge of all aspects of government, including the arts. His chief advisor on the arts was Jean Colbert (1619–1683), who was also his finance minister. In 1663 Colbert reorganized the Royal furniture workshops, which made a wide variety of luxury goods, and added to it the Gobelins tapestry workshops. At the same time, with the assistance of Le Brun, Colbert took charge of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, which had been founded by Cardinal Mazarin. Colbert also took a dominant role in architecture, taking the title of Superintendent of buildings in 1664. In 1666, the French Academy in Rome was founded, to take advantage of Rome's position as the leading art center of Europe, and to assure a stream of well-trained painters. Le Brun became the dean of French painters under Louis XIV, involved in architectural projects and interior design. His notable decorative works included the ceiling of the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles.[18]

The major painters of the later reign of Louis XIV included Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743) who came to Paris in 1681, and attracted the attention of LeBrun. LeBrun oriented him toward portrait painting, and he made a celebrated portrait of Louis XIV in 1701, surrounded by all the attributes of power, from the crown on the table to the red heels of his shoes. Rigaud soon had an elaborate workshop in place for making portraits of the nobility; he employed specialized artists to create the costumes and draperies, and others to paint the backgrounds, ranging from battlefields to gardens to salons, while he concentrated on the composition, colors and especially the faces.[18]

Georges de La Tour (1593–1652) was another important figure in the Louis XIV style; he was given a title, named court painter of the King, and received high payments for his portraits, though he rarely ever came to Paris, preferring to work in his home town of Lunéville. His paintings, with their unusual light and dark effects, were unusually somber, the figures barely seen in the darkness, lit by torchlight, evoking meditation and pity. In addition to religious scenes, he did genre paintings, including the famous Tricheur or card cheat, showing a young noble being cheated at cards while others look on passively. The writer and later French culture minister Andre Malraux wrote in 1951, "No other painter, not even Rembrandt, ever suggested such a vast and mysterious silence. La Tour is the only interpreter of the serene aspect of shadows."[19]

In his final years, Louis XIV's tastes changed again, under the influence of his morganic wife, Madame de Maintenon, toward more religious and meditative themes. He had all the paintings in his private room removed and replaced by a single canvas, Saint Sebastien being tended by Saint Irene (c. 1649) by Georges de La Tour.[20]

The Card Sharp with the Ace of Diamonds by Georges de La Tour (late 1630s)

The Card Sharp with the Ace of Diamonds by Georges de La Tour (late 1630s) Section of the ceiling of the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles, representing capture of fortress of Ghent by Louis XIV, by Charles Le Brun (1678)

Section of the ceiling of the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles, representing capture of fortress of Ghent by Louis XIV, by Charles Le Brun (1678)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Portrait of Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud, (1701)

Portrait of Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud, (1701)

Sculpture

The most influential sculptor of the period was the Italian Gian Lorenzo Bernini, whose work in Rome inspired sculptors all over Europe. He traveled to France; his proposal for a new facade of the Louvre was rejected by the King, who wanted a more specifically French style, but the Bernini did make a bust of Louis XIV in 1665 which was greatly admired and imitated in France.

One of the most prominent sculptors under Louis XIV was Antoine Coysevox (pronounced "quazevo") (1640–1720) from Lyon. He studied sculpture under Louis Lerambert and copied in marble ancient Roman works, including the Venus de Medici. In 1776, his bust of the King's official painter Charles Le Brun won him admission to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. He was soon producing monumental sculpture to accompany the new buildings constructed by Louis XIV; he made a Charlemagne for the royal chapel at Les Invalides, and then a large number of statues for the new Park at Versailles and then at the Château de Marly. He originally made the outdoor statues in weather-resistant stucco, then replaced them with marble works when they were finished in 1705. His work of Neptune from Marly is now in the Louvre, and his statues of Pan and a Flora and Dryad are now found in the Tuileries Gardens. His statue of The King's Fame riding Pegasus was originally made for the Château of Marly. After the Revolution it was moved to the Tuileries Gardens, and is now inside the Louvre. He also made a series of greatly admired portrait sculptures of the leading statesmen and artists of the time; Louis XIV at Versailles, Colbert (for his tomb at the Church of Saint Eustache; Cardinal Mazarin in the Collège des Quatre-Nations (now the Institut de France) in Paris; the playwright Jean Racine; the architect Vauban and the garden designer Andre Le Notre.[21]

Jacques Sarazin was another notable sculptor working on projects for Louis XIV. He made many statues and decorations for the Palace of Versailles, as well as the Caryatids for the eastern facade of the Pavilion du Horloge of the Louvre, facing the Cour Carré, which were based both on a study of the original Greek models, and on the work of Michelangelo.

Another notable sculptor of the Style Louis XV was Pierre Paul Puget (1620–1694), who was a sculptor, painter, engineer and architect. He was born in Marseille, and first sculpted ornaments for ships under construction. He then travelled to Italy, where he worked as an apprentice on the Baroque ceilings of the Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Pitti. He travelled back and forth between Italy and France, painting, sculpting and wood-carving. He made his celebrated statue of caryatids for the city hall of Toulon in 1665–1667, then was employed by Nicolas Fouquet to make a statue of Hercules for his chateau at Vaux-le-Vicomte. He continued to live in the south of France, making notable statues of Milo of Croton, Perseus, and Andromeda (now in the Louvre).[22]

Caryatids of Louvre by Jacques Sarazin

Caryatids of Louvre by Jacques Sarazin_03_black_bg.jpg.webp) Bust of Louis XIV by Bernini (1665), now in Palace of Versailles

Bust of Louis XIV by Bernini (1665), now in Palace of Versailles The King's Fame riding Pegasus, by Antoine Coysevox, made for Marly, now in the Louvre. (1702)

The King's Fame riding Pegasus, by Antoine Coysevox, made for Marly, now in the Louvre. (1702).jpg.webp) Louis XIV by Coysevox, now at Musée Carnavalet

Louis XIV by Coysevox, now at Musée Carnavalet

Perseus and Andromeda by Pierre Puget (Louvre)

Perseus and Andromeda by Pierre Puget (Louvre)

Tapestries

In 1662 Jean Baptiste Colbert purchased the tapestry workshop of a family of Flemish artisans and transformed it into a royal workshop for the manufacture of furniture and tapestries, under the name of Gobelins tapestry. Colbert placed the workshop under the direction of the royal court painter, Charles Le Brun, who served in that position from 1663 until 1690. The workshop worked closely with the major painters of the court, who produced the designs. After 1697 the enterprise was reorganized, and thereafter was devoted entirely to the production of tapestries for the King.[23]

The themes and styles of the tapestry were largely similar to the themes in the paintings of the period, celebrating the majesty of the King and triumphal scenes of military victories, mythological and pastoral scenes. While at first they were made only for use of the King and nobility, the factory soon began exporting its products to the other courts of Europe.

The royal Gobelins manufactory had competition from two private enterprises, the Beauvais Manufactory and the Aubusson tapestry workshop, which produced works in the same style but with a low-warp process, with slightly lesser quality. Jean Bérain the Elder, the royal draftsman and designer of the King, created a series of grotesque carpets for Aubusson. These tapestries sometimes celebrated contemporary themes, such as a work designed by Aubusson An late 17th to early 18th century tapestry done by the Beauvais Manufactory depicting Chinese astronomers at the Beijing Ancient Observatory using new more accurate instruments brought to them by Europeans (Jesuits) which were installed in 1644.

Louis XIV visits the Gobelins with Colbert, design by Charles Le Brun (between 1667 and 1672)

Louis XIV visits the Gobelins with Colbert, design by Charles Le Brun (between 1667 and 1672)

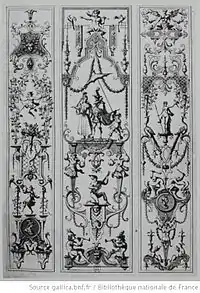

One of a set of five "Grotesques" by Jean Bérain from the Beauvais Manufactory (woven 1690–1711)

One of a set of five "Grotesques" by Jean Bérain from the Beauvais Manufactory (woven 1690–1711) Aubusson tapestry celebrating Jesuit mission to China (1697–1705)

Aubusson tapestry celebrating Jesuit mission to China (1697–1705)

Design and spectacle

In the early years of the King's reign, the most important public royal ceremony was the carrousel, a series of exercises and games on horseback. These events were designed to replace the tournament, which had been banned after 1559 when King Henry II was killed in a jousting accident. In the new, less dangerous version, riders usually had to pass their lance through the interior of a ring, or strike mannequins with the heads of Medusa, Moors and Turks. A grand carrousel was held on June 5–6, 1662 to celebrate the birth of the Dauphin, the son of Louis XIV. It was held on the square separating the Louvre from the Tuileries Palace, which afterwards became known as the Place du Carrousel.[24]

The ceremonial entry of the King into Paris also became an occasion for festivities. The return of Louis XIV and Queen Marie-Thérèse to Paris after his coronation in 1660 was celebrated by a grand event on a fairground at the gates of the city, where large thrones were constructed for the new monarchs. After the ceremony the site became known as the Place du Trône, or place of the Throne, until it became the Place de la Nation in 1880.[25]

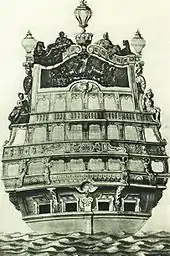

An office existed in the royal household of Louis XIV called Menus-Plaisirs du Roi, which was responsible the decoration at royal ceremonies and spectacles, including ballets, masques, illuminations, fireworks, theater performances and other entertainments. This office was held from 1674 to 1711 by Jean Bérain the Elder (1640–1711). He was also designer of the King's bedchamber and offices, and had an enormous influence upon what became known as Louis XIV style; his studio was located in the Grand Gallery of the Louvre, along with those of the royal furniture designer André Charles Boulle. He was particularly responsible for introducing the a modified version of the grotesque style of ornament, originally created in Italy by Raphael, into French interior design. He used the grotesque stele not only on wall panels, but also on tapestries made by the Aubusson tapestry workshops. His many varied other designs included the highly-ornate design of transom of the warship Soleil Royal (1670), named for the King.[26]

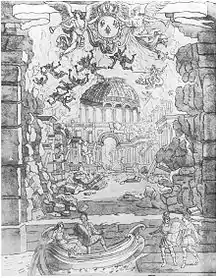

In addition to interior decoration, he designed the costumes and scenery for the royal theaters, including for the opera Amadis by Jean-Baptiste Lully performed at the Theater of the Palais Royal (1684), and for the opera-ballet Les Saisons by Lully's successor, Pascal Colasse, in 1695.[27]

Louis XIV in the Grand Carousel of 1662

Louis XIV in the Grand Carousel of 1662 Arabesque designs by Jean Bérain the Elder

Arabesque designs by Jean Bérain the Elder Bérain Set design for opera Amadis by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1684)

Bérain Set design for opera Amadis by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1684) Bérain design for transom of the warship Soleil Royal named for Louis XIV (1670)

Bérain design for transom of the warship Soleil Royal named for Louis XIV (1670)

The garden à la française

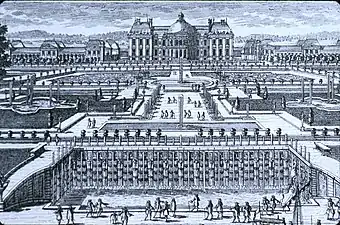

One of the most enduring and popular forms of the Style Louis XIV is the jardin à la française or French formal garden, a style based on symmetry and the principle of imposing order on nature. The most famous example is the Gardens of Versailles designed by André Le Nôtre, which inspired copies all across Europe. The first important garden à la française was the Château of Vaux-le-Vicomte, created for Nicolas Fouquet, the superintendent of finances to Louis XIV, beginning in 1656. Fouquet commissioned Louis Le Vau to design the chateau, Charles Le Brun to design statues for the garden, and André Le Nôtre to create the gardens. For the first time the garden and the chateau were perfectly integrated. A grand perspective of 1500 meters extended from the foot of the chateau to the statue of the Hercules of Farnese; and the space was filled with parterres of evergreen shrubs in ornamental patterns, bordered by colored sand, and the alleys were decorated at regular intervals by statues, basins, fountains, and carefully sculpted topiaries. "The symmetry attained at Vaux achieved a degree of perfection and unity rarely equalled in the art of classic gardens. The chateau is at the center of this strict spatial organization which symbolizes power and success."[28]

The Gardens of Versailles, created by André Le Nôtre between 1662 and 1700, were the greatest achievement of the French formal garden. They were the largest gardens in Europe, with an area of 15,000 hectares, and were laid out on an east–west axis followed the course of the sun: the sun rose over the Court of Honor, lit the Marble Court, crossed the Château and lit the bedroom of the King, and set at the end of the Grand Canal, reflected in the mirrors of the Hall of Mirrors.[29] In contrast with the grand perspectives, reaching to the horizon, the garden was full of surprises: fountains, small gardens filled with statuary, which provided a more human scale and intimate spaces. The central symbol of the garden was the sun; the emblem of Louis XIV, illustrated by the statue of Apollo in the central fountain of the garden. "The views and perspectives, to and from the palace, continued to infinity. The king ruled over nature, recreating in the garden not only his domination of his territories, but over the court and his subjects."[30]

17th-century engraving of gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte

17th-century engraving of gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte Gardens of the Palace of Versailles

Gardens of the Palace of Versailles The Bassin d'Apollon in the Gardens of Versailles

The Bassin d'Apollon in the Gardens of Versailles.jpg.webp) Parterres of the Versailles Orangerie

Parterres of the Versailles Orangerie Gardens of the Grand Trianon at the Palace of Versailles

Gardens of the Grand Trianon at the Palace of Versailles

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ducher, Robert, Caractéristique des styles (1988), p. 120

- ↑ Renault and Lazé, Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (2006), Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot, Paris (in French), pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, p. 120.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 Ducher 1988, p. 124.

- ↑ Texier, Simon (2012), pp. 38–39

- ↑ Texier, Simon (2012), pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, pp. 126–129.

- ↑ Renault and Lazé, Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (2006), pg. 59

- ↑ Renault and Lazé, Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (2006), p. 59

- ↑ McNab, 20–21; Moon; V&A, Nevers Jardiniere

- ↑ Pottier, 12

- ↑ Moon; McNab, 22

- ↑ Moon; McNab, 30

- ↑ Munger & Sullivan, 135–137

- ↑ Munger & Sullivan, 138–142

- ↑ Munger & Sullivan, 135–137

- 1 2 Bauer & Prater 2016, p. 16.

- ↑ cited in Bauer and Prater, Baroque (2016), p. 86.

- ↑ Bauer & Prater 2016, p. 86.

- ↑ "Coysevox, Charles Antoine". Chisholm, Hugh (ed., 1911). Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 355–56

- ↑ "Puget, Pierre". Chisholm, Hugh (ed., 1911). Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. p. 637

- ↑ "Gobelin". Chisholm, Hugh (ed., 1911). Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. p. 165

- ↑ Fierro 1996, p. 754.

- ↑ Dictionnaire historique de Paris 2013, p. 272.

- ↑ "Bérain, Jean". Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- ↑ "Bérain, Jean". Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopedia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- ↑ Prevot, Histoire des jardins, p. 146

- ↑ Prevot, Histoire des jardins, p. 152

- ↑ Lucia Impelluso, Jardins, potagers et labyrinthes, p. 64.

References

- Yves-Marie Allain and Janine Christiany, L'art des jardins en Europe, Citadelles et Mazenod, Paris, 2006

- Bauer, Hermann; Prater, Andreas (2016), Baroque (in French), Cologne: Taschen, ISBN 978-3-8365-4748-2

- Cabanne, Perre (1988), L'Art Classique et le Baroque, Paris: Larousse, ISBN 978-2-03-583324-2

- Ducher, Robert (1988), Caractéristique des Styles, Paris: Flammarion, ISBN 2-08-011539-1

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221--07862-4.

- Impelluso, Lucia,Jardins, potagers et labyrinthes, Hazan, Paris, 2007.

- McNab, Jessie, Seventeenth-Century French Ceramic Art, 1987, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0870994905, 9780870994906, google books

- Moon, Iris, "French Faience", in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 2016, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, online

- Munger, Jeffrey, Sullivan Elizabeth, European Porcelain in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Highlights of the collection, 2018, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 1588396436, 9781588396433, google books

- Pottier, André, Histoire de la faïence de Rouen, Volume 1, 1870, Le Brument (Rouen), google books (in French)

- Prevot, Philippe (2006), Histoire des jardins (in French), Paris: Editions Sud Ouest

- Renault, Christophe (2006), Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, Paris: Gisserot, ISBN 978-2-877-4746-58

- Texier, Simon (2012), Paris- Panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours, Paris: Parigramme, ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8

- Wenzler, Claude, Architecture du jardin, Editions Ouest-France, 2003

- Dictionnaire Historique de Paris. Le Livre de Poche. 2013. ISBN 978-2-253-13140-3.