| Part of a series on |

| Performing arts |

|---|

In the most general of terms, Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise expressive content.[1][2][3] Definitions of music vary depending on culture,[4] though it is an aspect of all human societies and a cultural universal.[5] While scholars agree that music is defined by a few specific elements, there is no consensus on their precise definitions.[6] The creation of music is commonly divided into musical composition, musical improvisation, and musical performance,[7] though the topic itself extends into academic disciplines, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and therapeutic contexts. Music may be performed or improvised using a vast range of instruments, including the human voice, thus is often credited for it's extreme versatility, and opportunity for creativity.[8]

In some musical contexts, a performance or composition may be to some extent improvised. For instance, in Hindustani classical music, the performer plays spontaneously while following a partially defined structure and using characteristic motifs. In modal jazz, the performers may take turns leading and responding while sharing a changing set of notes. In a free jazz context, there may be no structure whatsoever, with each performer acting at their discretion. Music may be deliberately composed to be unperformable or agglomerated electronically from many performances. Music is played in public and private areas, highlighted at events such as festivals, rock concerts, and orchestra performances, and heard incidentally as part of a score or soundtrack to a film, TV show, opera, or video game. Musical playback is the primary function of an MP3 player or CD player, and a universal feature of radios and smartphones.

Music often plays a key role in social activities, religious rituals, rite of passage ceremonies, celebrations, and cultural activities. The music industry includes songwriters, performers, sound engineers, producers, tour organizers, distributors of instruments, accessories, and sheet music. Compositions, performances, and recordings are assessed and evaluated by music critics, music journalists, and music scholars, as well as amateurs.

Etymology and terminology

The modern English word 'music' came into use in the 1630s.[9] It is derived from a long line of successive precursors: the Old English 'musike' of the mid-13th century; the Old French musique of the 12th century; and the Latin mūsica.[10][8][n 1] The Latin word itself derives from the Ancient Greek mousiké (technē)—μουσική (τέχνη)—literally meaning "(art) of the Muses".[10][n 2] The Muses were nine deities in Ancient Greek mythology who presided over the arts and sciences.[13][14] They were included in tales by the earliest Western authors, Homer and Hesiod,[15] and eventually came to be associated with music specifically.[14] Over time, Polyhymnia would reside over music more prominently than the other muses.[11] The Latin word musica was also the originator for both the Spanish música and French musique via spelling and linguistic adjustment, though other European terms were probably loanwords, including the Italian musica, German Musik, Dutch muziek, Norwegian musikk, Polish muzyka and Russian muzïka.[14]

The modern Western world usually defines music as an all-encompassing term used to describe diverse genres, styles, and traditions.[16] This is not the case worldwide, and languages such as modern Indonesian (musik) and Shona (musakazo) have recently adopted words to reflect this universal conception, as they did not have words that fit exactly the Western scope.[14] Before Western contact in East Asia, neither Japan nor China had a single word that encompasses music in a broad sense, but culturally, they often regarded music in such a fashion.[17] The closest word to mean music in Chinese, yue, shares a character with le, meaning joy, and originally referred to all the arts before narrowing in meaning.[17] Africa is too diverse to make firm generalizations, but the musicologist J. H. Kwabena Nketia has emphasized African music's often inseparable connection to dance and speech in general.[18] Some African cultures, such as the Songye people of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Tiv people of Nigeria, have a strong and broad conception of 'music' but no corresponding word in their native languages.[18] Other words commonly translated as 'music' often have more specific meanings in their respective cultures: the Hindi word for music, sangita, properly refers to art music,[19] while the many Indigenous languages of the Americas have words for music that refer specifically to song but describe instrumental music regardless.[20] Though the Arabic musiqi can refer to all music, it is usually used for instrumental and metric music, while khandan identifies vocal and improvised music.[21]

History

Origins and prehistory

It is often debated to what extent the origins of music will ever be understood,[24] and there are competing theories that aim to explain it.[25] Many scholars highlight a relationship between the origin of music and the origin of language, and there is disagreement surrounding whether music developed before, after, or simultaneously with language.[26] A similar source of contention surrounds whether music was the intentional result of natural selection or was a byproduct spandrel of evolution.[26] The earliest influential theory was proposed by Charles Darwin in 1871, who stated that music arose as a form of sexual selection, perhaps via mating calls.[27] Darwin's original perspective has been heavily criticized for its inconsistencies with other sexual selection methods,[28] though many scholars in the 21st century have developed and promoted the theory.[29] Other theories include that music arose to assist in organizing labor, improving long-distance communication, benefiting communication with the divine, assisting in community cohesion or as a defense to scare off predators.[30]

Prehistoric music can only be theorized based on findings from paleolithic archaeology sites. The Divje Babe flute, carved from a cave bear femur, is thought to be at least 40,000 years old, though there is considerable debate surrounding whether it is truly a musical instrument or an object formed by animals.[31] The earliest objects whose designations as musical instruments are widely accepted are bone flutes from the Swabian Jura, Germany, namely from the Geissenklösterle, Hohle Fels and Vogelherd caves.[32] Dated to the Aurignacian (of the Upper Paleolithic) and used by Early European modern humans, from all three caves there are eight examples, four made from the wing bones of birds and four from mammoth ivory; three of these are near complete.[32] Three flutes from the Geissenklösterle are dated as the oldest, c. 43,150–39,370 BP.[22][n 3]

Antiquity

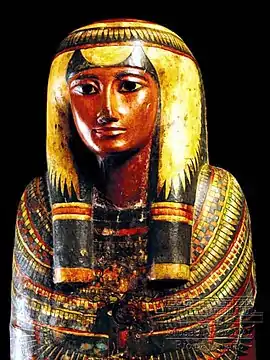

The earliest material and representational evidence of Egyptian musical instruments dates to the Predynastic period, but the evidence is more securely attested in the Old Kingdom when harps, flutes and double clarinets were played.[33] Percussion instruments, lyres, and lutes were added to orchestras by the Middle Kingdom. Cymbals[34] frequently accompanied music and dance, much as they still do in Egypt today. Egyptian folk music, including the traditional Sufi dhikr rituals, are the closest contemporary music genre to ancient Egyptian music, having preserved many of its features, rhythms and instruments.[35][36]

The "Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal", found on clay tablets in the ancient Syrian city of Ugarit, is the oldest surviving notated work of music, dating back to approximately 1400 BCE.[37][38]

Music was an important part of social and cultural life in ancient Greece, in fact it was one of the main subjects taught to children. Musical education was considered to be important for the development of an individual's soul. Musicians and singers played a prominent role in Greek theater,[39] and those who received a musical education were seen as nobles and in perfect harmony (as can be read in the Republic, Plato). Mixed gender choruses performed for entertainment, celebration, and spiritual ceremonies.[40] Instruments included the double-reed aulos and a plucked string instrument, the lyre, principally a special kind called a kithara. Music was an important part of education, and boys were taught music starting at age six. Greek musical literacy created significant musical development. Greek music theory included the Greek musical modes, that eventually became the basis for Western religious and classical music. Later, influences from the Roman Empire, Eastern Europe, and the Byzantine Empire changed Greek music. The Seikilos epitaph is the oldest surviving example of a complete musical composition, including musical notation, from anywhere in the world.[41] The oldest surviving work written on the subject of music theory is Harmonika Stoicheia by Aristoxenus.[42]

Asian cultures

Asian music covers a swath of music cultures surveyed in the articles on Arabia, Central Asia, East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Several have traditions reaching into antiquity.

Indian classical music is one of the oldest musical traditions in the world.[43] Sculptures from the Indus Valley civilization show dance[44] and old musical instruments, like the seven-holed flute. Stringed instruments and drums have been recovered from Harappa and Mohenjo Daro by excavations carried out by Mortimer Wheeler.[45] The Rigveda, an ancient Hindu text, has elements of present Indian music, with musical notation to denote the meter and mode of chanting.[46] Indian classical music (marga) is monophonic, and based on a single melody line or raga rhythmically organized through talas. The poem Cilappatikaram provides information about how new scales can be formed by modal shifting of the tonic from an existing scale.[47] Present day Hindi music was influenced by Persian traditional music and Afghan Mughals. Carnatic music, popular in the southern states, is largely devotional; the majority of the songs are addressed to the Hindu deities. There are songs emphasizing love and other social issues.

Indonesian music has been formed since the Bronze Age culture migrated to the Indonesian archipelago in the 2nd-3rd centuries BCE. Indonesian traditional music uses percussion instruments, especially kendang and gongs. Some of them developed elaborate and distinctive instruments, such as the sasando stringed instrument on the island of Rote, the Sundanese angklung, and the complex and sophisticated Javanese and Balinese gamelan orchestras. Indonesia is the home of gong chime, a general term for a set of small, high pitched pot gongs. Gongs are usually placed in order of note, with the boss up on a string held in a low wooden frame. The most popular form of Indonesian music is gamelan, an ensemble of tuned percussion instruments that include metallophones, drums, gongs and spike fiddles along with bamboo suling (like a flute).[48][49]

Chinese classical music, the traditional art or court music of China, has a history stretching over about 3,000 years. It has its own unique systems of musical notation, as well as musical tuning and pitch, musical instruments and styles or genres. Chinese music is pentatonic-diatonic, having a scale of twelve notes to an octave (5 + 7 = 12) as does European-influenced music.[50]

Western classical

Early music

The medieval music era (500 to 1400), which took place during the Middle Ages, started with the introduction of monophonic (single melodic line) chanting into Catholic Church services. Musical notation was used since ancient times in Greek culture, but in the Middle Ages, notation was first introduced by the Catholic Church, so chant melodies could be written down, to facilitate the use of the same melodies for religious music across the Catholic empire. The only European Medieval repertory that has been found, in written form, from before 800 is the monophonic liturgical plainsong chant of the Catholic Church, the central tradition of which was called Gregorian chant. Alongside these traditions of sacred and church music there existed a vibrant tradition of secular song (non-religious songs). Examples of composers from this period are Léonin, Pérotin, Guillaume de Machaut, and Walther von der Vogelweide.[51][52][53][54]

Renaissance music (c. 1400 to 1600) was more focused on secular themes, such as courtly love. Around 1450, the printing press was invented, which made printed sheet music much less expensive and easier to mass-produce (prior to the invention of the press, all notated music was hand-copied). The increased availability of sheet music spread musical styles quicker and across a larger area. Musicians and singers often worked for the church, courts and towns. Church choirs grew in size, and the church remained an important patron of music. By the middle of the 15th century, composers wrote richly polyphonic sacred music, in which different melody lines were interwoven simultaneously. Prominent composers from this era include Guillaume Du Fay, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Thomas Morley, Orlando di Lasso and Josquin des Prez. As musical activity shifted from the church to aristocratic courts, kings, queens and princes competed for the finest composers. Many leading composers came from the Netherlands, Belgium, and France; they are called the Franco-Flemish composers.[55] They held important positions throughout Europe, especially in Italy. Other countries with vibrant musical activity included Germany, England, and Spain.

Common practice period

Baroque

The Baroque era of music took place from 1600 to 1750, as the Baroque artistic style flourished across Europe; and during this time, music expanded in its range and complexity. Baroque music began when the first operas (dramatic solo vocal music accompanied by orchestra) were written. During the Baroque era, polyphonic contrapuntal music, in which multiple, simultaneous independent melody lines were used, remained important (counterpoint was important in the vocal music of the Medieval era). German Baroque composers wrote for small ensembles including strings, brass, and woodwinds, as well as for choirs and keyboard instruments such as pipe organ, harpsichord, and clavichord. During this period several major music forms were defined that lasted into later periods when they were expanded and evolved further, including the fugue, the invention, the sonata, and the concerto.[56] The late Baroque style was polyphonically complex and richly ornamented. Important composers from the Baroque era include Johann Sebastian Bach (Cello suites), George Frideric Handel (Messiah), Georg Philipp Telemann and Antonio Vivaldi (The Four Seasons).

Classicism

The music of the Classical period (1730 to 1820) aimed to imitate what were seen as the key elements of the art and philosophy of Ancient Greece and Rome: the ideals of balance, proportion and disciplined expression. (Note: the music from the Classical period should not be confused with Classical music in general, a term which refers to Western art music from the 5th century to the 2000s, which includes the Classical period as one of a number of periods). Music from the Classical period has a lighter, clearer and considerably simpler texture than the Baroque music which preceded it. The main style was homophony,[57] where a prominent melody and a subordinate chordal accompaniment part are clearly distinct. Classical instrumental melodies tended to be almost voicelike and singable. New genres were developed, and the fortepiano, the forerunner to the modern piano, replaced the Baroque era harpsichord and pipe organ as the main keyboard instrument (though pipe organ continued to be used in sacred music, such as Masses).

Importance was given to instrumental music. It was dominated by further development of musical forms initially defined in the Baroque period: the sonata, the concerto, and the symphony. Other main kinds were the trio, string quartet, serenade and divertimento. The sonata was the most important and developed form. Although Baroque composers also wrote sonatas, the Classical style of sonata is completely distinct. All of the main instrumental forms of the Classical era, from string quartets to symphonies and concertos, were based on the structure of the sonata. The instruments used chamber music and orchestra became more standardized. In place of the basso continuo group of the Baroque era, which consisted of harpsichord, organ or lute along with a number of bass instruments selected at the discretion of the group leader (e.g., viol, cello, theorbo, serpent), Classical chamber groups used specified, standardized instruments (e.g., a string quartet would be performed by two violins, a viola and a cello). The practice of improvised chord-playing by the continuo keyboardist or lute player, a hallmark of Baroque music, underwent a gradual decline between 1750-1800.[58]

One of the most important changes made in the Classical period was the development of public concerts. The aristocracy still played a significant role in the sponsorship of concerts and compositions, but it was now possible for composers to survive without being permanent employees of queens or princes. The increasing popularity of classical music led to a growth in the number and types of orchestras. The expansion of orchestral concerts necessitated the building of large public performance spaces. Symphonic music including symphonies, musical accompaniment to ballet and mixed vocal/instrumental genres, such as opera and oratorio, became more popular.[59][60][61]

The best known composers of Classicism are Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Christoph Willibald Gluck, Johann Christian Bach, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert. Beethoven and Schubert are also considered to be composers in the later part of the Classical era, as it began to move towards Romanticism.

Romanticism

Romantic music (c. 1820 to 1900) from the 19th century had many elements in common with the Romantic styles in literature and painting of the era. Romanticism was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement was characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism as well as glorification of all the past and nature. Romantic music expanded beyond the rigid styles and forms of the Classical era into more passionate, dramatic expressive pieces and songs. Romantic composers such as Wagner and Brahms attempted to increase emotional expression and power in their music to describe deeper truths or human feelings. With symphonic tone poems, composers tried to tell stories and evoke images or landscapes using instrumental music. Some composers promoted nationalistic pride with patriotic orchestral music inspired by folk music. The emotional and expressive qualities of music came to take precedence over tradition.[62]

Romantic composers grew in idiosyncrasy, and went further in the syncretism of exploring different art-forms in a musical context, (such as literature), history (historical figures and legends), or nature itself. Romantic love or longing was a prevalent theme in many works composed during this period. In some cases, the formal structures from the classical period continued to be used (e.g., the sonata form used in string quartets and symphonies), but these forms were expanded and altered. In many cases, new approaches were explored for existing genres, forms, and functions. Also, new forms were created that were deemed better suited to the new subject matter. Composers continued to develop opera and ballet music, exploring new styles and themes.[39]

In the years after 1800, the music developed by Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert introduced a more dramatic, expressive style. In Beethoven's case, short motifs, developed organically, came to replace melody as the most significant compositional unit (an example is the distinctive four note figure used in his Fifth Symphony). Later Romantic composers such as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Antonín Dvořák, and Gustav Mahler used more unusual chords and more dissonance to create dramatic tension. They generated complex and often much longer musical works. During the late Romantic period, composers explored dramatic chromatic alterations of tonality, such as extended chords and altered chords, which created new sound "colors." The late 19th century saw a dramatic expansion in the size of the orchestra, and the industrial revolution helped to create better instruments, creating a more powerful sound. Public concerts became an important part of well-to-do urban society. It also saw a new diversity in theatre music, including operetta, and musical comedy and other forms of musical theatre.[39]

20th and 21st century

In the 19th century, a key way new compositions became known to the public, was by the sales of sheet music, which middle class amateur music lovers would perform at home, on their piano or other common instruments, such as the violin. With 20th-century music, the invention of new electric technologies such as radio broadcasting and mass market availability of gramophone records meant sound recordings heard by listeners (on the radio or record player), became the main way to learn about new songs and pieces.[63] There was a vast increase in music listening as the radio gained popularity and phonographs were used to replay and distribute music, anyone with a radio or record player could hear operas, symphonies and big bands in their own living room. During the 19th century, the focus on sheet music had restricted access to new music to middle and upper-class people who could read music and who owned pianos and other instruments. Radios and record players allowed lower-income people, who could not afford an opera or symphony concert ticket to hear this music. It meant people could hear music from different parts of the country, or even different parts of the world, even if they could not afford to travel to these locations. This helped to spread musical styles.[64]

The focus of art music in the 20th century was characterized by exploration of new rhythms, styles, and sounds. The horrors of World War I influenced many of the arts, including music, and composers began exploring darker, harsher sounds. Traditional music styles such as jazz and folk music were used by composers as a source of ideas for classical music. Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, and John Cage were influential composers in 20th-century art music. The invention of sound recording and the ability to edit music gave rise to new subgenres of classical music, including the acousmatic[65] and Musique concrète schools of electronic composition. Sound recording was a major influence on the development of popular music genres, because it enabled recordings of songs and bands to be widely distributed. The introduction of the multitrack recording system had a major influence on rock music, because it could do more than record a band's performance. Using a multitrack system, a band and their music producer could overdub many layers of instrument tracks and vocals, creating new sounds that would not be possible in a live performance.[66][67]

Jazz evolved and became an important genre of music over the course of the 20th century, and during the second half, rock music did the same. Jazz is an American musical artform that originated in the beginning of the 20th century, in African American communities in the Southern United States from a confluence of African and European music traditions. The style's West African pedigree is evident in its use of blue notes, improvisation, polyrhythms, syncopation, and the swung note.[68]

Rock music is a genre of popular music that developed in the 1950s from rock and roll, rockabilly, blues, and country music.[69] The sound of rock often revolves around the electric or acoustic guitar, and it uses a strong back beat laid down by a rhythm section. Along with the guitar or keyboards, saxophone and blues-style harmonica are used as soloing instruments. In its "purest form", it "has three chords, a strong, insistent back beat, and a catchy melody."[70] The traditional rhythm section for popular music is rhythm guitar, electric bass guitar, drums. Some bands have keyboard instruments such as organ, piano, or, since the 1970s, analog synthesizers. In the 1980s, pop musicians began using digital synthesizers, such as the DX-7 synthesizer, electronic drum machines such as the TR-808 and synth bass devices (such as the TB-303) or synth bass keyboards. In the 1990s, an increasingly large range of computerized hardware musical devices and instruments and software (e.g. digital audio workstations) were used. In the 2020s, soft synths and computer music apps make it possible for bedroom producers to create and record types of music, such as electronic dance music, in their home, adding sampled and digital instruments and editing the recording digitally. In the 1990s, bands in genres such as nu metal began including DJs in their bands. DJs create music by manipulating recorded music, using a DJ mixer.[71][72]

Innovation in music technology continued into the 21st century, including the development of isomorphic keyboards and Dynamic Tonality.

Creation

Composition

"Composition" is the act or practice of creating a song, an instrumental music piece, a work with both singing and instruments, or another type of music. In many cultures, including Western classical music, the act of composing also includes the creation of music notation, such as a sheet music "score", which is then performed by the composer or by other singers or musicians. In popular music and traditional music, the act of composing, which is typically called songwriting, may involve the creation of a basic outline of the song, called the lead sheet, which sets out the melody, lyrics and chord progression. In classical music, the composer typically orchestrates his or her own compositions, but in musical theatre and in pop music, songwriters may hire an arranger to do the orchestration. In some cases, a songwriter may not use notation at all, and instead, compose the song in her mind and then play or record it from memory. In jazz and popular music, notable recordings by influential performers are given the weight that written scores play in classical music.[73][74]

Even when music is notated relatively precisely, as in classical music, there are many decisions that a performer has to make, because notation does not specify all of the elements of music precisely. The process of deciding how to perform music that has been previously composed and notated is termed "interpretation". Different performers' interpretations of the same work of music can vary widely, in terms of the tempos that are chosen and the playing or singing style or phrasing of the melodies. Composers and songwriters who present their own music are interpreting their songs, just as much as those who perform the music of others. The standard body of choices and techniques present at a given time and a given place is referred to as performance practice, whereas interpretation is generally used to mean the individual choices of a performer.[75]

Although a musical composition often uses musical notation and has a single author, this is not always the case. A work of music can have multiple composers, which often occurs in popular music when a band collaborates to write a song, or in musical theatre, when one person writes the melodies, a second person writes the lyrics, and a third person orchestrates the songs. In some styles of music, such as the blues, a composer/songwriter may create, perform and record new songs or pieces without ever writing them down in music notation. A piece of music can also be composed with words, images, or computer programs that explain or notate how the singer or musician should create musical sounds. Examples range from avant-garde music that uses graphic notation, to text compositions such as Aus den sieben Tagen, to computer programs that select sounds for musical pieces. Music that makes heavy use of randomness and chance is called aleatoric music,[76] and is associated with contemporary composers active in the 20th century, such as John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Witold Lutosławski. A commonly known example of chance-based music is the sound of wind chimes jingling in a breeze.

The study of composition has traditionally been dominated by examination of methods and practice of Western classical music, but the definition of composition is broad enough to include the creation of popular music and traditional music songs and instrumental pieces as well as spontaneously improvised works like those of free jazz performers and African percussionists such as Ewe drummers.

Performance

Performance is the physical expression of music, which occurs when a song is sung or piano piece, guitar melody, symphony, drum beat or other musical part is played. In classical music, a work is written in music notation by a composer and then performed once the composer is satisfied with its structure and instrumentation. However, as it gets performed, the interpretation of a song or piece can evolve and change. In classical music, instrumental performers, singers or conductors may gradually make changes to the phrasing or tempo of a piece. In popular and traditional music, the performers have more freedom to make changes to the form of a song or piece. As such, in popular and traditional music styles, even when a band plays a cover song, they can make changes such as adding a guitar solo or inserting an introduction.[77]

A performance can either be planned out and rehearsed (practiced)—which is the norm in classical music, jazz big bands, and many popular music styles–or improvised over a chord progression (a sequence of chords), which is the norm in small jazz and blues groups. Rehearsals of orchestras, concert bands and choirs are led by a conductor. Rock, blues and jazz bands are usually led by the bandleader. A rehearsal is a structured repetition of a song or piece by the performers until it can be sung or played correctly and, if it is a song or piece for more than one musician, until the parts are together from a rhythmic and tuning perspective.

Many cultures have strong traditions of solo performance (in which one singer or instrumentalist performs), such as in Indian classical music, and in the Western art-music tradition. Other cultures, such as in Bali, include strong traditions of group performance. All cultures include a mixture of both, and performance may range from improvised solo playing to highly planned and organized performances such as the modern classical concert, religious processions, classical music festivals or music competitions. Chamber music, which is music for a small ensemble with only one or a few of each type of instrument, is often seen as more intimate than large symphonic works.[78]

Improvisation

Musical improvisation is the creation of spontaneous music, often within (or based on) a pre-existing harmonic framework, chord progression, or riffs. Improvisers use the notes of the chord, various scales that are associated with each chord, and chromatic ornaments and passing tones which may be neither chord tones nor from the typical scales associated with a chord. Musical improvisation can be done with or without preparation. Improvisation is a major part of some types of music, such as blues, jazz, and jazz fusion, in which instrumental performers improvise solos, melody lines, and accompaniment parts..[79]

In the Western art music tradition, improvisation was an important skill during the Baroque era and during the Classical era. In the Baroque era, performers improvised ornaments, and basso continuo keyboard players improvised chord voicings based on figured bass notation. As well, the top soloists were expected to be able to improvise pieces such as preludes. In the Classical era, solo performers and singers improvised virtuoso cadenzas during concerts.

However, in the 20th and early 21st century, as "common practice" Western art music performance became institutionalized in symphony orchestras, opera houses, and ballets, improvisation has played a smaller role, as more and more music was notated in scores and parts for musicians to play. At the same time, some 20th and 21st century art music composers have increasingly included improvisation in their creative work. In Indian classical music, improvisation is a core component and an essential criterion of performances.

Art and entertainment

.jpg.webp)

Music is composed and performed for many purposes, ranging from aesthetic pleasure, religious or ceremonial purposes, or as an entertainment product for the marketplace. When music was only available through sheet music scores, such as during the Classical and Romantic eras, music lovers would buy the sheet music of their favourite pieces and songs so that they could perform them at home on the piano. With the advent of the phonograph, records of popular songs, rather than sheet music became the dominant way that music lovers would enjoy their favourite songs. With the advent of home tape recorders in the 1980s and digital music in the 1990s, music lovers could make tapes or playlists of favourite songs and take them with them on a portable cassette player or MP3 player. Some music lovers create mix tapes of favourite songs, which serve as a "self-portrait, a gesture of friendship, prescription for an ideal party... [and] an environment consisting solely of what is most ardently loved".[80]

Amateur musicians can compose or perform music for their own pleasure and derive income elsewhere. Professional musicians are employed by institutions and organisations, including armed forces (in marching bands, concert bands and popular music groups), religious institutions, symphony orchestras, broadcasting or film production companies, and music schools. Professional musicians sometimes work as freelancers or session musicians, seeking contracts and engagements in a variety of settings. There are often many links between amateur and professional musicians. Beginning amateur musicians take lessons with professional musicians. In community settings, advanced amateur musicians perform with professional musicians in a variety of ensembles such as community concert bands and community orchestras.

A distinction is often made between music performed for a live audience and music that is performed in a studio so that it can be recorded and distributed through the music retail system or the broadcasting system. However, there are also many cases where a live performance in front of an audience is also recorded and distributed. Live concert recordings are popular in both classical music and in popular music forms such as rock, where illegally taped live concerts are prized by music lovers. In the jam band scene, live, improvised jam sessions are preferred to studio recordings.[81]

Notation

Music notation typically means the written expression of music notes and rhythms on paper using symbols. When music is written down, the pitches and rhythm of the music, such as the notes of a melody, are notated. Music notation often provides instructions on how to perform the music. For example, the sheet music for a song may state the song is a "slow blues" or a "fast swing", which indicates the tempo and the genre. To read notation, a person must have an understanding of music theory, harmony and the performance practice associated with a particular song or piece's genre.

Written notation varies with the style and period of music. Nowadays, notated music is produced as sheet music or, for individuals with computer scorewriter programs, as an image on a computer screen. In ancient times, music notation was put onto stone or clay tablets.[38] To perform music from notation, a singer or instrumentalist requires an understanding of the rhythmic and pitch elements embodied in the symbols and the performance practice that is associated with a piece of music or genre. In genres requiring musical improvisation, the performer often plays from music where only the chord changes and form of the song are written, requiring the performer to have a great understanding of the music's structure, harmony and the styles of a particular genre e.g., jazz or country music.

In Western art music, the most common types of written notation are scores, which include all the music parts of an ensemble piece, and parts, which are the music notation for the individual performers or singers. In popular music, jazz, and blues, the standard musical notation is the lead sheet, which notates the melody, chords, lyrics (if it is a vocal piece), and structure of the music. Fake books are also used in jazz; they may consist of lead sheets or simply chord charts, which permit rhythm section members to improvise an accompaniment part to jazz songs. Scores and parts are also used in popular music and jazz, particularly in large ensembles such as jazz "big bands." In popular music, guitarists and electric bass players often read music notated in tablature (often abbreviated as "tab"), which indicates the location of the notes to be played on the instrument using a diagram of the guitar or bass fingerboard. Tablature was used in the Baroque era to notate music for the lute, a stringed, fretted instrument.[82]

Oral and aural tradition

Many types of music, such as traditional blues and folk music were not written down in sheet music; instead, they were originally preserved in the memory of performers, and the songs were handed down orally, from one musician or singer to another, or aurally, in which a performer learns a song "by ear". When the composer of a song or piece is no longer known, this music is often classified as "traditional" or as a "folk song". Different musical traditions have different attitudes towards how and where to make changes to the original source material, from quite strict, to those that demand improvisation or modification to the music. A culture's history and stories may also be passed on by ear through song.[83]

Elements

Music has many different fundamentals or elements. Depending on the definition of "element" being used, these can include pitch, beat or pulse, tempo, rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, style, allocation of voices, timbre or color, dynamics, expression, articulation, form, and structure. The elements of music feature prominently in the music curriculums of Australia, the UK, and the US. All three curriculums identify pitch, dynamics, timbre, and texture as elements, but the other identified elements of music are far from universally agreed upon. Below is a list of the three official versions of the "elements of music":

- Australia: pitch, timbre, texture, dynamics and expression, rhythm, form and structure.[84]

- UK: pitch, timbre, texture, dynamics, duration, tempo, structure.[85]

- USA: pitch, timbre, texture, dynamics, rhythm, form, harmony, style/articulation.[86]

In relation to the UK curriculum, in 2013 the term: "appropriate musical notations" was added to their list of elements and the title of the list was changed from the "elements of music" to the "inter-related dimensions of music". The inter-related dimensions of music are listed as: pitch, duration, dynamics, tempo, timbre, texture, structure, and appropriate musical notations.[87]

The phrase "the elements of music" is used in a number of different contexts. The two most common contexts can be differentiated by describing them as the "rudimentary elements of music" and the "perceptual elements of music".[n 4]

Pitch

Pitch is an aspect of a sound that we can hear, reflecting whether one musical sound, note, or tone is "higher" or "lower" than another musical sound, note, or tone. We can talk about the highness or lowness of pitch in the more general sense, such as the way a listener hears a piercingly high piccolo note or whistling tone as higher in pitch than a deep thump of a bass drum. We also talk about pitch in the precise sense associated with musical melodies, basslines and chords. Precise pitch can only be determined in sounds that have a frequency that is clear and stable enough to distinguish from noise. For example, it is much easier for listeners to discern the pitch of a single note played on a piano than to try to discern the pitch of a crash cymbal that is struck.[92]

Melody

A melody, also called a "tune", is a series of pitches (notes) sounding in succession (one after the other), often in a rising and falling pattern. The notes of a melody are typically created using pitch systems such as scales or modes. Melodies also often contain notes from the chords used in the song. The melodies in simple folk songs and traditional songs may use only the notes of a single scale, the scale associated with the tonic note or key of a given song. For example, a folk song in the key of C (also referred to as C major) may have a melody that uses only the notes of the C major scale (the individual notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and C; these are the "white notes" on a piano keyboard. On the other hand, Bebop-era jazz from the 1940s and contemporary music from the 20th and 21st centuries may use melodies with many chromatic notes (i.e., notes in addition to the notes of the major scale; on a piano, a chromatic scale would include all the notes on the keyboard, including the "white notes" and "black notes" and unusual scales, such as the whole tone scale (a whole tone scale in the key of C would contain the notes C, D, E, F♯, G♯ and A♯). A low musical line played by bass instruments, such as double bass, electric bass, or tuba, is called a bassline.[93]

Harmony

Harmony refers to the "vertical" sounds of pitches in music, which means pitches that are played or sung together at the same time to create a chord. Usually, this means the notes are played at the same time, although harmony may also be implied by a melody that outlines a harmonic structure (i.e., by using melody notes that are played one after the other, outlining the notes of a chord). In music written using the system of major-minor tonality ("keys"), which includes most classical music written from 1600 to 1900 and most Western pop, rock, and traditional music, the key of a piece determines the "home note" or tonic to which the piece generally resolves, and the character (e.g. major or minor) of the scale in use. Simple classical pieces and many pop and traditional music songs are written so that all the music is in a single key. More complex Classical, pop, and traditional music songs and pieces may have two keys (and in some cases three or more keys). Classical music from the Romantic era (written from about 1820–1900) often contains multiple keys,[94] as does jazz, especially Bebop jazz from the 1940s, in which the key or "home note" of a song may change every four bars or even every two bars.[95]

Rhythm

Rhythm is the arrangement of sounds and silences in time. Meter animates time in regular pulse groupings, called measures or bars, which in Western classical, popular, and traditional music often group notes in sets of two (e.g., 2/4 time), three (e.g., 3/4 time, also known as Waltz time, or 3/8 time), or four (e.g., 4/4 time). Meters are made easier to hear because songs and pieces often (but not always) place an emphasis on the first beat of each grouping. Notable exceptions exist, such as the backbeat used in much Western pop and rock, in which a song that uses a measure that consists of four beats (called 4/4 time or common time) will have accents on beats two and four, which are typically performed by the drummer on the snare drum, a loud and distinctive-sounding percussion instrument. In pop and rock, the rhythm parts of a song are played by the rhythm section, which includes chord-playing instruments (e.g., electric guitar, acoustic guitar, piano, or other keyboard instruments), a bass instrument (typically electric bass or for some styles such as jazz and bluegrass, double bass) and a drum kit player.[96]

Texture

Musical texture is the overall sound of a piece of music or song. The texture of a piece or song is determined by how the melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic materials are combined in a composition, thus determining the overall nature of the sound in a piece. Texture is often described in regard to the density, or thickness, and range, or width, between lowest and highest pitches, in relative terms as well as more specifically distinguished according to the number of voices, or parts, and the relationship between these voices (see common types below). For example, a thick texture contains many 'layers' of instruments. One layer can be a string section or another brass. The thickness is affected by the amount and the richness of the instruments.[97] Texture is commonly described according to the number of and relationship between parts or lines of music:

- monophony: a single melody (or "tune") with neither instrumental accompaniment nor a harmony part. A mother singing a lullaby to her baby would be an example.

- heterophony: two or more instruments or singers playing/singing the same melody, but with each performer slightly varying the rhythm or speed of the melody or adding different ornaments to the melody. Two bluegrass fiddlers playing the same traditional fiddle tune together will typically each vary the melody by some degree and each add different ornaments.

- polyphony: multiple independent melody lines that interweave together, which are sung or played at the same time. Choral music written in the Renaissance music era was typically written in this style. A round, which is a song such as "Row, Row, Row Your Boat", which different groups of singers all start to sing at a different time, is an example of polyphony.

- homophony: a clear melody supported by chordal accompaniment. Most Western popular music songs from the 19th century onward are written in this texture.

Music that contains a large number of independent parts (e.g., a double concerto accompanied by 100 orchestral instruments with many interweaving melodic lines) is generally said to have a "thicker" or "denser" texture than a work with few parts (e.g., a solo flute melody accompanied by a single cello).

Timbre

.jpg.webp)

Timbre, sometimes called "color" or "tone color" is the quality or sound of a voice or instrument.[98] Timbre is what makes a particular musical sound different from another, even when they have the same pitch and loudness. For example, a 440 Hz A note sounds different when it is played on oboe, piano, violin, or electric guitar. Even if different players of the same instrument play the same note, their notes might sound different due to differences in instrumental technique (e.g., different embouchures), different types of accessories (e.g., mouthpieces for brass players, reeds for oboe and bassoon players) or strings made out of different materials for string players (e.g., gut strings versus steel strings). Even two instrumentalists playing the same note on the same instrument (one after the other) may sound different due to different ways of playing the instrument (e.g., two string players might hold the bow differently).

The physical characteristics of sound that determine the perception of timbre include the spectrum, envelope, and overtones of a note or musical sound. For electric instruments developed in the 20th century, such as electric guitar, electric bass and electric piano, the performer can also change the tone by adjusting equalizer controls, tone controls on the instrument, and by using electronic effects units such as distortion pedals. The tone of the electric Hammond organ is controlled by adjusting drawbars.

Expression

Expressive qualities are those elements in music that create change in music without changing the main pitches or substantially changing the rhythms of the melody and its accompaniment. Performers, including singers and instrumentalists, can add musical expression to a song or piece by adding phrasing, by adding effects such as vibrato (with voice and some instruments, such as guitar, violin, brass instruments, and woodwinds), dynamics (the loudness or softness of piece or a section of it), tempo fluctuations (e.g., ritardando or accelerando, which are, respectively slowing down and speeding up the tempo), by adding pauses or fermatas on a cadence, and by changing the articulation of the notes (e.g., making notes more pronounced or accented, by making notes more legato, which means smoothly connected, or by making notes shorter).

Expression is achieved through the manipulation of pitch (such as inflection, vibrato, slides etc.), volume (dynamics, accent, tremolo etc.), duration (tempo fluctuations, rhythmic changes, changing note duration such as with legato and staccato, etc.), timbre (e.g. changing vocal timbre from a light to a resonant voice) and sometimes even texture (e.g. doubling the bass note for a richer effect in a piano piece). Expression therefore can be seen as a manipulation of all elements to convey "an indication of mood, spirit, character etc."[99] and as such cannot be included as a unique perceptual element of music,[100] although it can be considered an important rudimentary element of music.

Form

In music, form describes the overall structure or plan of a song or piece of music,[101] and it describes the layout of a composition as divided into sections.[102] In the early 20th century, Tin Pan Alley songs and Broadway musical songs were often in AABA thirty-two-bar form, in which the A sections repeated the same eight bar melody (with variation) and the B section provided a contrasting melody or harmony for eight bars. From the 1960s onward, Western pop and rock songs are often in verse-chorus form, which comprises a sequence of verse and chorus ("refrain") sections, with new lyrics for most verses and repeating lyrics for the choruses. Popular music often makes use of strophic form, sometimes in conjunction with the twelve bar blues.[103]

In the tenth edition of The Oxford Companion to Music, Percy Scholes defines musical form as "a series of strategies designed to find a successful mean between the opposite extremes of unrelieved repetition and unrelieved alteration."[104] Examples of common forms of Western music include the fugue, the invention, sonata-allegro, canon, strophic, theme and variations, and rondo.

Scholes states that European classical music had only six stand-alone forms: simple binary, simple ternary, compound binary, rondo, air with variations, and fugue (although musicologist Alfred Mann emphasized that the fugue is primarily a method of composition that has sometimes taken on certain structural conventions.[105])

Where a piece cannot readily be broken into sectional units (though it might borrow some form from a poem, story or programme), it is said to be through-composed. Such is often the case with a fantasia, prelude, rhapsody, etude (or study), symphonic poem, Bagatelle, impromptu or similar compostion.[106] Professor Charles Keil classified forms and formal detail as "sectional, developmental, or variational."[107]

Philosophy

The philosophy of music is the study of fundamental questions regarding music and has connections with questions in metaphysics and aesthetics. Questions include:

- What is the definition of music? (What are the necessary and sufficient conditions for classifying something as music?)

- What is the relationship between music and mind?

- What does music history reveal to us about the world?

- What is the connection between music and emotions?

- What is meaning in relation to music?

In ancient times, such as with the Ancient Greeks, the aesthetics of music explored the mathematical and cosmological dimensions of rhythmic and harmonic organization. In the 18th century, focus shifted to the experience of hearing music, and thus to questions about its beauty and human enjoyment (plaisir and jouissance) of music. The origin of this philosophic shift is sometimes attributed to Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten in the 18th century, followed by Immanuel Kant. Through their writing, the ancient term 'aesthetics', meaning sensory perception, received its present-day connotation. In the 2000s, philosophers have tended to emphasize issues besides beauty and enjoyment. For example, music's capacity to express emotion has been foregrounded. [108]

In the 20th century, important contributions were made by Peter Kivy, Jerrold Levinson, Roger Scruton, and Stephen Davies. However, many musicians, music critics, and other non-philosophers have contributed to the aesthetics of music. In the 19th century, a significant debate arose between Eduard Hanslick, a music critic and musicologist, and composer Richard Wagner regarding whether music can express meaning. Harry Partch and some other musicologists, such as Kyle Gann, have studied and tried to popularize microtonal music and the usage of alternate musical scales. Modern composers like La Monte Young, Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca paid much attention to a scale called just intonation.[109][110][111]

It is often thought that music has the ability to affect our emotions, intellect, and psychology; it can assuage our loneliness or incite our passions. The philosopher Plato suggests in The Republic that music has a direct effect on the soul. Therefore, he proposes that in the ideal regime music would be closely regulated by the state (Book VII).[112] In Ancient China, the philosopher Confucius believed that music and rituals or rites are interconnected and harmonious with nature; he stated that music was the harmonization of heaven and earth, while the order was brought by the rites order, making them extremely crucial functions in society.[113]

Psychology

Modern music psychology aims to explain and understand musical behavior and experience.[114] Research in this field and its subfields are primarily empirical; their knowledge tends to advance on the basis of interpretations of data collected by systematic observation of and interaction with human participants. In addition to its focus on fundamental perceptions and cognitive processes, music psychology is a field of research with practical relevance for many areas, including music performance, composition, education, criticism, and therapy, as well as investigations of human aptitude, skill, intelligence, creativity, and social behavior.

Neuroscience

Cognitive neuroscience of music is the scientific study of brain-based mechanisms involved in the cognitive processes underlying music. These behaviours include music listening, performing, composing, reading, writing, and ancillary activities. It also is increasingly concerned with the brain basis for musical aesthetics and musical emotion. The field is distinguished by its reliance on direct observations of the brain, using such techniques as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), magnetoencephalography (MEG), electroencephalography (EEG), and positron emission tomography (PET).

Cognitive musicology

Cognitive musicology is a branch of cognitive science concerned with computationally modeling musical knowledge with the goal of understanding both music and cognition.[115] The use of computer models provides an exacting, interactive medium in which to formulate and test theories and has roots in artificial intelligence and cognitive science.[116]

This interdisciplinary field investigates topics such as the parallels between language and music in the brain. Biologically inspired models of computation are often included in research, such as neural networks and evolutionary programs.[117] This field seeks to model how musical knowledge is represented, stored, perceived, performed, and generated. By using a well-structured computer environment, the systematic structures of these cognitive phenomena can be investigated.[118]

Psychoacoustics

Psychoacoustics is the scientific study of sound perception. More specifically, it is the branch of science studying the psychological and physiological responses associated with sound (including speech and music). It can be further categorized as a branch of psychophysics.

Evolutionary musicology

Evolutionary musicology concerns the "origins of music, the question of animal song, selection pressures underlying music evolution", and "music evolution and human evolution".[119] It seeks to understand music perception and activity in the context of evolutionary theory. Charles Darwin speculated that music may have held an adaptive advantage and functioned as a protolanguage,[120] a view which has spawned several competing theories of music evolution.[121][122][123] An alternate view sees music as a by-product of linguistic evolution; a type of "auditory cheesecake" that pleases the senses without providing any adaptive function.[124] This view has been directly countered by numerous music researchers.[125][126][127]

Cultural effects

An individual's culture or ethnicity plays a role in their music cognition, including their preferences, emotional reaction, and musical memory. Musical preferences are biased toward culturally familiar musical traditions beginning in infancy, and adults' classification of the emotion of a musical piece depends on both culturally specific and universal structural features.[128][129] Additionally, individuals' musical memory abilities are greater for culturally familiar music than for culturally unfamiliar music.[130][131]

Perceptual

Since the emergence of the study of psychoacoustics in the 1930s, most lists of elements of music have related more to how we hear music than how we learn to play it or study it. C.E. Seashore, in his book Psychology of Music,[132] identified four "psychological attributes of sound". These were: "pitch, loudness, time, and timbre" (p. 3). He did not call them the "elements of music" but referred to them as "elemental components" (p. 2). Nonetheless, these elemental components link precisely with four of the most common musical elements: "Pitch" and "timbre" match exactly, "loudness" links with dynamics, and "time" links with the time-based elements of rhythm, duration, and tempo. This usage of the phrase "the elements of music" links more closely with Webster's New 20th Century Dictionary definition of an element as: "a substance which cannot be divided into a simpler form by known methods"[133] and educational institutions' lists of elements generally align with this definition as well.

Although writers of lists of "rudimentary elements of music" can vary their lists depending on their personal (or institutional) priorities, the perceptual elements of music should consist of an established (or proven) list of discrete elements which can be independently manipulated to achieve an intended musical effect. It seems at this stage that there is still research to be done in this area.

A slightly different way of approaching the identification of the elements of music, is to identify the "elements of sound" as: pitch, duration, loudness, timbre, sonic texture and spatial location,[134] and then to define the "elements of music" as: sound, structure, and artistic intent.[134]

Sociological aspects

Ethnographic studies demonstrate that music is a participatory, community-based activity.[135][136] Music is experienced by individuals in a range of social settings from being alone, to attending a large concert, forming a music community, which cannot be understood as a function of individual will or accident; it includes both commercial and non-commercial participants with a shared set of common values. Musical performances take different forms in different cultures and socioeconomic milieus.

In Europe and North America, there was a divide between what types of music were viewed as "high culture" and "low culture." "High culture" included Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and modern-era symphonies, concertos, and solo works, and are typically heard in formal concerts in concert halls and churches, with the audience sitting quietly. Other types of music—including jazz, blues, soul, and country—are often performed in bars, nightclubs, and theatres, where the audience may drink, dance and cheer. Until the 20th century, the division between "high" and "low" musical forms was accepted as a valid distinction that separated out "art music", from popular music heard in bars and dance halls. Musicologists, such as David Brackett, note a "redrawing of high-low cultural-aesthetic boundaries" in the 20th century.[137] And, "when industry and public discourses link categories of music with categories of people, they tend to conflate stereotypes with actual listening communities."[137] Stereotypes can be based on socioeconomic standing, or social class, of the performers or audience of the different types of music.

When composers introduce styles of music that break with convention, there can be strong resistance from academics and others. Late-period Beethoven string quartets, Stravinsky ballet scores, serialism, bebop, hip hop, punk rock, and electronica were controversial and criticised, when they were first introduced. Such themes are examined in the sociology of music, sometimes called sociomusicology, which is pursued in departments of sociology, media studies, or music, and is closely related to ethnomusicology.

Role of women

Women have played a major role in music throughout history, as composers, songwriters, instrumental performers, singers, conductors, music scholars, music educators, music critics/music journalists and other musical professions. In the 2010s, while women comprise a significant proportion of popular music and classical music singers, and a significant proportion of songwriters (many of them being singer-songwriters), there are few women record producers, rock critics and rock instrumentalists. Although there have been a huge number of women composers in classical music, from the medieval period to the present day, women composers are significantly underrepresented in the commonly performed classical music repertoire, music history textbooks and music encyclopedias; for example, in the Concise Oxford History of Music, Clara Schumann is one of the few female composers who is mentioned.

Women comprise a significant proportion of instrumental soloists in classical music and the percentage of women in orchestras is increasing. A 2015 article on concerto soloists in major Canadian orchestras, however, indicated that 84% of the soloists with the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal were men. In 2012, women still made up just 6% of the top-ranked Vienna Philharmonic orchestra. Women are less common as instrumental players in popular music genres such as rock and heavy metal, although there have been a number of notable female instrumentalists and all-female bands. Women are particularly underrepresented in extreme metal genres.[138] In the 1960s pop-music scene, "[l]ike most aspects of the...music business, [in the 1960s,] songwriting was a male-dominated field. Though there were plenty of female singers on the radio, women ...were primarily seen as consumers:... Singing was sometimes an acceptable pastime for a girl, but playing an instrument, writing songs, or producing records simply wasn't done."[139] Young women "...were not socialized to see themselves as people who create [music]."[139]

Women are also underrepresented in orchestral conducting, music criticism/music journalism, music producing, and sound engineering. While women were discouraged from composing in the 19th century, and there are few women musicologists, women became involved in music education "...to such a degree that women dominated [this field] during the later half of the 19th century and well into the 20th century."[140]

According to Jessica Duchen, a music writer for London's The Independent, women musicians in classical music are "...too often judged for their appearances, rather than their talent" and they face pressure "...to look sexy onstage and in photos."[141] Duchen states that while "[t]here are women musicians who refuse to play on their looks,...the ones who do tend to be more materially successful."[141] According to the UK's Radio 3 editor, Edwina Wolstencroft, the music industry has long been open to having women in performance or entertainment roles, but women are much less likely to have positions of authority, such as being the conductor of an orchestra.[142] In popular music, while there are many women singers recording songs, there are very few women behind the audio console acting as music producers, the individuals who direct and manage the recording process.[143] One of the most recorded artists is Asha Bhosle, an Indian singer best known as a playback singer in Hindi cinema.[144]

Media and technology

Since the 20th century, live music can be broadcast over the radio, television or the Internet, or recorded and listened to on a CD player or MP3 player.

In the early 20th century (in the late 1920s), as talking pictures emerged in the early 20th century, with their prerecorded musical tracks, an increasing number of moviehouse orchestra musicians found themselves out of work.[146] During the 1920s, live musical performances by orchestras, pianists, and theater organists were common at first-run theaters.[147] With the coming of the talking motion pictures, those featured performances were largely eliminated. The American Federation of Musicians (AFM) took out newspaper advertisements protesting the replacement of live musicians with mechanical playing devices. One 1929 ad that appeared in the Pittsburgh Press features an image of a can labeled "Canned Music / Big Noise Brand / Guaranteed to Produce No Intellectual or Emotional Reaction Whatever"[148]

Sometimes, live performances incorporate prerecorded sounds. For example, a disc jockey uses disc records for scratching, and some 20th-century works have a solo for an instrument or voice that is performed along with music that is prerecorded onto a tape. Some pop bands use recorded backing tracks. Computers and many keyboards can be programmed to produce and play Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) music. Audiences can also become performers by participating in karaoke, an activity of Japanese origin centered on a device that plays voice-eliminated versions of well-known songs. Most karaoke machines also have video screens that show lyrics to songs being performed; performers can follow the lyrics as they sing over the instrumental tracks.

The advent of the Internet and widespread high-speed broadband access has transformed the experience of music, partly through the increased ease of access to recordings of music via streaming video and vastly increased choice of music for consumers. Another effect of the Internet arose with online communities and social media websites like YouTube and Facebook, a social networking service. These sites make it easier for aspiring singers and amateur bands to distribute videos of their songs, connect with other musicians, and gain audience interest. Professional musicians also use YouTube as a free publisher of promotional material. YouTube users, for example, no longer only download and listen to MP3s, but also actively create their own. According to Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams, in their book Wikinomics, there has been a shift from a traditional consumer role to what they call a "prosumer" role, a consumer who both creates content and consumes. Manifestations of this in music include the production of mashes, remixes, and music videos by fans.[149]

Education

Non-institutional

The incorporation of music into general education from preschool to post secondary education, is common in North America and Europe. Involvement in playing and singing music is thought to teach basic skills such as concentration, counting, listening, and cooperation while also promoting understanding of language, improving the ability to recall information, and creating an environment more conducive to learning in other areas.[150] In elementary schools, children often learn to play instruments such as the recorder, sing in small choirs, and learn about the history of Western art music and traditional music. Some elementary school children also learn about popular music styles. In religious schools, children sing hymns and other religious music. In secondary schools (and less commonly in elementary schools), students may have the opportunity to perform in some types of musical ensembles, such as choirs (a group of singers), marching bands, concert bands, jazz bands, or orchestras. In some school systems, music lessons on how to play instruments may be provided. Some students also take private music lessons after school with a singing teacher or instrument teacher. Amateur musicians typically learn basic musical rudiments (e.g., learning about musical notation for musical scales and rhythms) and beginner- to intermediate-level singing or instrument-playing techniques.

At the university level, students in most arts and humanities programs can receive credit for taking a few music courses, which typically take the form of an overview course on the history of music, or a music appreciation course that focuses on listening to music and learning about different musical styles. In addition, most North American and European universities have some types of musical ensembles that students in arts and humanities are able to participate in, such as choirs, marching bands, concert bands, or orchestras. The study of Western art music is increasingly common outside of North America and Europe, such as the Indonesian Institute of the Arts in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, or the classical music programs that are available in Asian countries such as South Korea, Japan, and China. At the same time, Western universities and colleges are widening their curriculum to include music of non-Western cultures, such as the music of Africa or Bali (e.g. Gamelan music).

Institutional

People aiming to become professional musicians, singers, composers, songwriters, music teachers and practitioners of other music-related professions such as music history professors, sound engineers, and so on study in specialized post-secondary programs offered by colleges, universities and music conservatories. Some institutions that train individuals for careers in music offer training in a wide range of professions, as is the case with many of the top U.S. universities, which offer degrees in music performance (including singing and playing instruments), music history, music theory, music composition, music education (for individuals aiming to become elementary or high school music teachers) and, in some cases, conducting. On the other hand, some small colleges may only offer training in a single profession (e.g., sound recording).

While most university and conservatory music programs focus on training students in classical music, there are universities and colleges that train musicians for careers as jazz or popular music musicians and composers, with notable U.S. examples including the Manhattan School of Music and the Berklee College of Music. Two schools in Canada which offer professional jazz training are McGill University and Humber College. Individuals aiming at careers in some types of music, such as heavy metal music, country music or blues are unlikely to become professionals by completing degrees or diplomas. Instead, they typically learn about their style of music by singing or playing in bands (often beginning in amateur bands, cover bands and tribute bands), studying recordings on DVD and the Internet, and working with already-established professionals in their style of music, either through informal mentoring or regular music lessons. Since the 2000s, the increasing popularity and availability of Internet forums and YouTube "how-to" videos have enabled singers and musicians from metal, blues and similar genres to improve their skills. Many pop, rock and country singers train informally with vocal coaches and voice teachers.[151][152]

Academic study

Musicology

Musicology, the academic study of music, is studied in universities and music conservatories. The earliest definitions from the 19th century defined three sub-disciplines of musicology: systematic musicology, historical musicology, and comparative musicology or ethnomusicology. In 2010-era scholarship, one is more likely to encounter a division into music theory, music history, and ethnomusicology. Research in musicology has often been enriched by cross-disciplinary work, for example in the field of psychoacoustics. The study of music of non-Western cultures, and cultural study of music, is called ethnomusicology. Students can pursue study of musicology, ethnomusicology, music history, and music theory through different types of degrees, including bachelor's, master's and PhD.[153][154][155]

Music theory

Music theory is the study of music, generally in a highly technical manner outside of other disciplines. More broadly it refers to any study of music, usually related in some form with compositional concerns, and may include mathematics, physics, and anthropology. What is most commonly taught in beginning music theory classes are guidelines to write in the style of the common practice period, or tonal music. Theory, even of music of the common practice period, may take other forms.[156] Musical set theory is the application of mathematical set theory to music, first applied to atonal music. Speculative music theory, contrasted with analytic music theory, is devoted to the analysis and synthesis of music materials, for example tuning systems, generally as preparation for composition.[157]

Zoomusicology

Zoomusicology is the study of the music of non-human animals, or the musical aspects of sounds produced by non-human animals. As George Herzog (1941) asked, "do animals have music?" François-Bernard Mâche's Musique, mythe, nature, ou les Dauphins d'Arion (1983), a study of "ornitho-musicology" using a technique of Nicolas Ruwet's Language, musique, poésie (1972) paradigmatic segmentation analysis, shows that bird songs are organised according to a repetition-transformation principle. Jean-Jacques Nattiez (1990), argues that "in the last analysis, it is a human being who decides what is and is not musical, even when the sound is not of human origin. If we acknowledge that sound is not organised and conceptualised (that is, made to form music) merely by its producer, but by the mind that perceives it, then music is uniquely human."[158]

Ethnomusicology

In the West, much of the history of music that is taught deals with the Western civilization's art music, known as classical music. The history of music in non-Western cultures ("world music" or the field of "ethnomusicology") is also taught in Western universities. This includes the documented classical traditions of Asian countries outside the influence of Western Europe, as well as the folk or indigenous music of various other cultures. Popular or folk styles of music in non-Western countries varied from culture to culture, and period to period. Different cultures emphasised different instruments, techniques, singing styles and uses for music. Music has been used for entertainment, ceremonies, rituals, religious purposes and for practical and artistic communication. Non-Western music has also been used for propaganda purposes, as was the case with Chinese opera during the Cultural Revolution.

There is a host of music classifications for non-Western music, many of which are caught up in the argument over the definition of music. Among the largest of these is the division between classical music (or "art" music), and popular music (or commercial music – including non-Western styles of rock, country, and pop music-related styles). Some genres do not fit neatly into one of these "big two" classifications, (such as folk music, world music, or jazz-related music).

As world cultures have come into greater global contact, their indigenous musical styles have often merged with other styles, which produces new styles. For example, the United States bluegrass style contains elements from Anglo-Irish, Scottish, Irish, German and African instrumental and vocal traditions, which were able to fuse in the United States' multi-ethnic "melting pot" society. Some types of world music contain a mixture of non-Western indigenous styles with Western pop music elements. Genres of music are determined as much by tradition and presentation as by the actual music. Some works, like George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, are claimed by both jazz and classical music, while Gershwin's Porgy and Bess and Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story are claimed by both opera and the Broadway musical tradition. Many music festivals for non-Western music, include bands and singers from a particular musical genre, such as world music.[159][160]

Indian music, for example, is one of the oldest and longest living types of music, and is still widely heard and performed in South Asia, as well as internationally (especially since the 1960s). Indian music has mainly three forms of classical music, Hindustani, Carnatic, and Dhrupad styles. It has also a large repertoire of styles, which involve only percussion music such as the talavadya performances famous in South India.

Therapy

Music therapy is an interpersonal process in which a trained therapist uses music and all of its facets—physical, emotional, mental, social, aesthetic, and spiritual—to help clients to improve or maintain their health. In some instances, the client's needs are addressed directly through music; in others they are addressed through the relationships that develop between the client and therapist. Music therapy is used with individuals of all ages and with a variety of conditions, including: psychiatric disorders, medical problems, physical disabilities, sensory impairments, developmental disabilities, substance abuse issues, communication disorders, interpersonal problems, and aging. It is also used to improve learning, build self-esteem, reduce stress, support physical exercise, and facilitate a host of other health-related activities. Music therapists may encourage clients to sing, play instruments, create songs, or do other musical activities.