| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology |

|---|

|

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species.[1][2][3] Social anthropology studies patterns of behavior, while cultural anthropology studies cultural meaning, including norms and values.[1][2][3] A portmanteau term sociocultural anthropology is commonly used today.[4] Linguistic anthropology studies how language influences social life. Biological or physical anthropology studies the biological development of humans.[1][2][3]

Archaeological anthropology, often termed as "anthropology of the past," studies human activity through investigation of physical evidence.[5][6] It is considered a branch of anthropology in North America and Asia, while in Europe, archaeology is viewed as a discipline in its own right or grouped under other related disciplines, such as history and palaeontology.[7]

Etymology

The abstract noun anthropology is first attested in reference to history.[8][n 1] Its present use first appeared in Renaissance Germany in the works of Magnus Hundt and Otto Casmann.[9] Their Neo-Latin anthropologia derived from the combining forms of the Greek words ánthrōpos (ἄνθρωπος, "human") and lógos (λόγος, "study").[8] Its adjectival form appeared in the works of Aristotle.[8] It began to be used in English, possibly via French Anthropologie, by the early 18th century.[8][n 2]

Origin and development of the term

.jpg.webp)

Through the 19th century

In 1647, the Bartholins, early scholars of the University of Copenhagen, defined l'anthropologie as follows:[11]

Anthropology, that is to say the science that treats of man, is divided ordinarily and with reason into Anatomy, which considers the body and the parts, and Psychology, which speaks of the soul.[n 3]

Sporadic use of the term for some of the subject matter occurred subsequently, such as the use by Étienne Serres in 1839 to describe the natural history, or paleontology, of man, based on comparative anatomy, and the creation of a chair in anthropology and ethnography in 1850 at the French National Museum of Natural History by Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau. Various short-lived organizations of anthropologists had already been formed. The Société Ethnologique de Paris, the first to use the term ethnology, was formed in 1839 and focused on methodically studying human races. After the death of its founder, William Frédéric Edwards, in 1842, it gradually declined in activity until it eventually dissolved in 1862.[12]

Meanwhile, the Ethnological Society of New York, currently the American Ethnological Society, was founded on its model in 1842, as well as the Ethnological Society of London in 1843, a break-away group of the Aborigines' Protection Society.[13] These anthropologists of the times were liberal, anti-slavery, and pro-human-rights activists. They maintained international connections.

Anthropology and many other current fields are the intellectual results of the comparative methods developed in the earlier 19th century. Theorists in such diverse fields as anatomy, linguistics, and ethnology, making feature-by-feature comparisons of their subject matters, were beginning to suspect that similarities between animals, languages, and folkways were the result of processes or laws unknown to them then.[14] For them, the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was the epiphany of everything they had begun to suspect. Darwin himself arrived at his conclusions through comparison of species he had seen in agronomy and in the wild.

Darwin and Wallace unveiled evolution in the late 1850s. There was an immediate rush to bring it into the social sciences. Paul Broca in Paris was in the process of breaking away from the Société de biologie to form the first of the explicitly anthropological societies, the Société d'Anthropologie de Paris, meeting for the first time in Paris in 1859.[15][n 4] When he read Darwin, he became an immediate convert to Transformisme, as the French called evolutionism.[16] His definition now became "the study of the human group, considered as a whole, in its details, and in relation to the rest of nature".[17]

Broca, being what today would be called a neurosurgeon, had taken an interest in the pathology of speech. He wanted to localize the difference between man and the other animals, which appeared to reside in speech. He discovered the speech center of the human brain, today called Broca's area after him. His interest was mainly in Biological anthropology, but a German philosopher specializing in psychology, Theodor Waitz, took up the theme of general and social anthropology in his six-volume work, entitled Die Anthropologie der Naturvölker, 1859–1864. The title was soon translated as "The Anthropology of Primitive Peoples". The last two volumes were published posthumously.

Waitz defined anthropology as "the science of the nature of man". Following Broca's lead, Waitz points out that anthropology is a new field, which would gather material from other fields, but would differ from them in the use of comparative anatomy, physiology, and psychology to differentiate man from "the animals nearest to him". He stresses that the data of comparison must be empirical, gathered by experimentation.[18] The history of civilization, as well as ethnology, are to be brought into the comparison. It is to be presumed fundamentally that the species, man, is a unity, and that "the same laws of thought are applicable to all men".[19]

Waitz was influential among British ethnologists. In 1863, the explorer Richard Francis Burton and the speech therapist James Hunt broke away from the Ethnological Society of London to form the Anthropological Society of London, which henceforward would follow the path of the new anthropology rather than just ethnology. It was the 2nd society dedicated to general anthropology in existence. Representatives from the French Société were present, though not Broca. In his keynote address, printed in the first volume of its new publication, The Anthropological Review, Hunt stressed the work of Waitz, adopting his definitions as a standard.[20][n 5] Among the first associates were the young Edward Burnett Tylor, inventor of cultural anthropology, and his brother Alfred Tylor, a geologist. Previously Edward had referred to himself as an ethnologist; subsequently, an anthropologist.

Similar organizations in other countries followed: The Anthropological Society of Madrid (1865), the American Anthropological Association in 1902, the Anthropological Society of Vienna (1870), the Italian Society of Anthropology and Ethnology (1871), and many others subsequently. The majority of these were evolutionists. One notable exception was the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory (1869) founded by Rudolph Virchow, known for his vituperative attacks on the evolutionists. Not religious himself, he insisted that Darwin's conclusions lacked empirical foundation.

During the last three decades of the 19th century, a proliferation of anthropological societies and associations occurred, most independent, most publishing their own journals, and all international in membership and association. The major theorists belonged to these organizations. They supported the gradual osmosis of anthropology curricula into the major institutions of higher learning. By 1898, 48 educational institutions in 13 countries had some curriculum in anthropology. None of the 75 faculty members were under a department named anthropology.[21]

20th and 21st centuries

Anthropology studies as a specialized field of academic study, however much developed through the end of the 19th century. Then it rapidly expanded beginning in the early 20th century to the point where many of the world's higher educational institutions typically included anthropology departments. Thousands of anthropology departments have come into existence, and anthropology has also diversified from a few major subdivisions to dozens more. Practical anthropology, the use of anthropological knowledge and technique to solve specific problems, has arrived; for example, the presence of buried victims might stimulate the use of a forensic archaeologist to recreate the final scene. The organization has also reached a global level. For example, the World Council of Anthropological Associations (WCAA), "a network of national, regional and international associations that aims to promote worldwide communication and cooperation in anthropology", currently contains members from about three dozen nations.[22]

Since the work of Franz Boas and Bronisław Malinowski in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, social anthropology in Great Britain and cultural anthropology in the US have been distinguished from other social sciences by their emphasis on cross-cultural comparisons, long-term in-depth examination of context, and the importance they place on participant-observation or experiential immersion in the area of research. Cultural anthropology, in particular, has emphasized cultural relativism, holism, and the use of findings to frame cultural critiques.[23] This has been particularly prominent in the United States, from Boas' arguments against 19th-century racial ideology, through Margaret Mead's advocacy for gender equality and sexual liberation, to current criticisms of post-colonial oppression and promotion of multiculturalism. Ethnography is one of its primary research designs as well as the text that is generated from anthropological fieldwork.[24][25][26]

In Great Britain and the Commonwealth countries, the British tradition of social anthropology tends to dominate. In the United States, anthropology has traditionally been divided into the four field approach developed by Franz Boas in the early 20th century: biological or physical anthropology; social, cultural, or sociocultural anthropology; archaeological anthropology; and linguistic anthropology. These fields frequently overlap but tend to use different methodologies and techniques.[27]

European countries with overseas colonies tended to practice more ethnology (a term coined and defined by Adam F. Kollár in 1783). It is sometimes referred to as sociocultural anthropology in the parts of the world that were influenced by the European tradition.[28]

Fields

Anthropology is a global discipline involving humanities, social sciences and natural sciences. Anthropology builds upon knowledge from natural sciences, including the discoveries about the origin and evolution of Homo sapiens, human physical traits, human behavior, the variations among different groups of humans, how the evolutionary past of Homo sapiens has influenced its social organization and culture, and from social sciences, including the organization of human social and cultural relations, institutions, social conflicts, etc.[29][30] Early anthropology originated in Classical Greece and Persia and studied and tried to understand observable cultural diversity, such as by Al-Biruni of the Islamic Golden Age.[31][32] As such, anthropology has been central in the development of several new (late 20th century) interdisciplinary fields such as cognitive science,[33] global studies, and various ethnic studies.

According to Clifford Geertz,

...anthropology is perhaps the last of the great nineteenth-century conglomerate disciplines still for the most part organizationally intact. Long after natural history, moral philosophy, philology, and political economy have dissolved into their specialized successors, it has remained a diffuse assemblage of ethnology, human biology, comparative linguistics, and prehistory, held together mainly by the vested interests, sunk costs, and administrative habits of academia, and by a romantic image of comprehensive scholarship.[34]

Sociocultural anthropology has been heavily influenced by structuralist and postmodern theories, as well as a shift toward the analysis of modern societies. During the 1970s and 1990s, there was an epistemological shift away from the positivist traditions that had largely informed the discipline. During this shift, enduring questions about the nature and production of knowledge came to occupy a central place in cultural and social anthropology. In contrast, archaeology and biological anthropology remained largely positivist. Due to this difference in epistemology, the four sub-fields of anthropology have lacked cohesion over the last several decades.

Sociocultural

Sociocultural anthropology draws together the principal axes of cultural anthropology and social anthropology. Cultural anthropology is the comparative study of the manifold ways in which people make sense of the world around them, while social anthropology is the study of the relationships among individuals and groups.[35] Cultural anthropology is more related to philosophy, literature and the arts (how one's culture affects the experience for self and group, contributing to a more complete understanding of the people's knowledge, customs, and institutions), while social anthropology is more related to sociology and history.[35] In that, it helps develop an understanding of social structures, typically of others and other populations (such as minorities, subgroups, dissidents, etc.). There is no hard-and-fast distinction between them, and these categories overlap to a considerable degree.

Inquiry in sociocultural anthropology is guided in part by cultural relativism, the attempt to understand other societies in terms of their own cultural symbols and values.[24] Accepting other cultures in their own terms moderates reductionism in cross-cultural comparison.[36] This project is often accommodated in the field of ethnography. Ethnography can refer to both a methodology and the product of ethnographic research, i.e. an ethnographic monograph. As a methodology, ethnography is based upon long-term fieldwork within a community or other research site. Participant observation is one of the foundational methods of social and cultural anthropology.[37] Ethnology involves the systematic comparison of different cultures. The process of participant-observation can be especially helpful to understanding a culture from an emic (conceptual, vs. etic, or technical) point of view.

The study of kinship and social organization is a central focus of sociocultural anthropology, as kinship is a human universal. Sociocultural anthropology also covers economic and political organization, law and conflict resolution, patterns of consumption and exchange, material culture, technology, infrastructure, gender relations, ethnicity, childrearing and socialization, religion, myth, symbols, values, etiquette, worldview, sports, music, nutrition, recreation, games, food, festivals, and language (which is also the object of study in linguistic anthropology).

Comparison across cultures is a key element of method in sociocultural anthropology, including the industrialized (and de-industrialized) West. The Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (SCCS) includes 186 such cultures.[38]

Biological

Biological anthropology and physical anthropology are synonymous terms to describe anthropological research focused on the study of humans and non-human primates in their biological, evolutionary, and demographic dimensions. It examines the biological and social factors that have affected the evolution of humans and other primates, and that generate, maintain or change contemporary genetic and physiological variation.[39]

Archaeological

Archaeology is the study of the human past through its material remains. Artifacts, faunal remains, and human altered landscapes are evidence of the cultural and material lives of past societies. Archaeologists examine material remains in order to deduce patterns of past human behavior and cultural practices. Ethnoarchaeology is a type of archaeology that studies the practices and material remains of living human groups in order to gain a better understanding of the evidence left behind by past human groups, who are presumed to have lived in similar ways.[40]

Linguistic

Linguistic anthropology (not to be confused with anthropological linguistics) seeks to understand the processes of human communications, verbal and non-verbal, variation in language across time and space, the social uses of language, and the relationship between language and culture.[41] It is the branch of anthropology that brings linguistic methods to bear on anthropological problems, linking the analysis of linguistic forms and processes to the interpretation of sociocultural processes. Linguistic anthropologists often draw on related fields including sociolinguistics, pragmatics, cognitive linguistics, semiotics, discourse analysis, and narrative analysis.[42]

Ethnography

Ethnography is a method of analysing social or cultural interaction. It often involves participant observation though an ethnographer may also draw from texts written by participants of in social interactions. Ethnography views first-hand experience and social context as important.[43]

Tim Ingold distinguishes ethnography from anthropology arguing that anthropology tries to construct general theories of human experience, applicable in general and novel settings, while ethnography concerns itself with fidelity. He argues that the anthropologist must make his writing consistent with their understanding of literature and other theory but notes that ethnography may be of use to the anthropologists and the fields inform one another.[44]

Key topics by field: sociocultural

Art, media, music, dance and film

| Part of a series on the |

| Anthropology of art, media, music, dance and film |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Art

One of the central problems in the anthropology of art concerns the universality of 'art' as a cultural phenomenon. Several anthropologists have noted that the Western categories of 'painting', 'sculpture', or 'literature', conceived as independent artistic activities, do not exist, or exist in a significantly different form, in most non-Western contexts.[45] To surmount this difficulty, anthropologists of art have focused on formal features in objects which, without exclusively being 'artistic', have certain evident 'aesthetic' qualities. Boas' Primitive Art, Claude Lévi-Strauss' The Way of the Masks (1982) or Geertz's 'Art as Cultural System' (1983) are some examples in this trend to transform the anthropology of 'art' into an anthropology of culturally specific 'aesthetics'.

Media

Media anthropology (also known as the anthropology of media or mass media) emphasizes ethnographic studies as a means of understanding producers, audiences, and other cultural and social aspects of mass media. The types of ethnographic contexts explored range from contexts of media production (e.g., ethnographies of newsrooms in newspapers, journalists in the field, film production) to contexts of media reception, following audiences in their everyday responses to media. Other types include cyber anthropology, a relatively new area of internet research, as well as ethnographies of other areas of research which happen to involve media, such as development work, social movements, or health education. This is in addition to many classic ethnographic contexts, where media such as radio, the press, new media, and television have started to make their presences felt since the early 1990s.[46]

Music

Ethnomusicology is an academic field encompassing various approaches to the study of music (broadly defined), that emphasize its cultural, social, material, cognitive, biological, and other dimensions or contexts instead of or in addition to its isolated sound component or any particular repertoire.

Ethnomusicology can be used in a wide variety of fields, such as teaching, politics, cultural anthropology etc. While the origins of ethnomusicology date back to the 18th and 19th centuries, it was formally termed "ethnomusicology" by Dutch scholar Jaap Kunst c. 1950. Later, the influence of study in this area spawned the creation of the periodical Ethnomusicology and the Society of Ethnomusicology.[47]

Visual

Visual anthropology is concerned, in part, with the study and production of ethnographic photography, film and, since the mid-1990s, new media. While the term is sometimes used interchangeably with ethnographic film, visual anthropology also encompasses the anthropological study of visual representation, including areas such as performance, museums, art, and the production and reception of mass media. Visual representations from all cultures, such as sandpaintings, tattoos, sculptures and reliefs, cave paintings, scrimshaw, jewelry, hieroglyphs, paintings, and photographs are included in the focus of visual anthropology.

Economic, political economic, applied and development

| Part of a series on |

| Economic, applied, and development anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Economic

Economic anthropology attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It has a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which it is highly critical. Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology begin with the Polish-British founder of anthropology, Bronisław Malinowski, and his French compatriot, Marcel Mauss, on the nature of gift-giving exchange (or reciprocity) as an alternative to market exchange. Economic Anthropology remains, for the most part, focused upon exchange. The school of thought derived from Marx and known as Political Economy focuses on production, in contrast.[48] Economic anthropologists have abandoned the primitivist niche they were relegated to by economists, and have now turned to examine corporations, banks, and the global financial system from an anthropological perspective.[49]

Political economy

Political economy in anthropology is the application of the theories and methods of historical materialism to the traditional concerns of anthropology, including, but not limited to, non-capitalist societies. Political economy introduced questions of history and colonialism to ahistorical anthropological theories of social structure and culture. Three main areas of interest rapidly developed. The first of these areas was concerned with the "pre-capitalist" societies that were subject to evolutionary "tribal" stereotypes. Sahlin's work on hunter-gatherers as the "original affluent society" did much to dissipate that image. The second area was concerned with the vast majority of the world's population at the time, the peasantry, many of whom were involved in complex revolutionary wars such as in Vietnam. The third area was on colonialism, imperialism, and the creation of the capitalist world-system.[50] More recently, these political economists have more directly addressed issues of industrial (and post-industrial) capitalism around the world.

Applied

Applied anthropology refers to the application of the method and theory of anthropology to the analysis and solution of practical problems. It is a "complex of related, research-based, instrumental methods which produce change or stability in specific cultural systems through the provision of data, initiation of direct action, and/or the formulation of policy".[51] Applied anthropology is the practical side of anthropological research; it includes researcher involvement and activism within the participating community. It is closely related to development anthropology (distinct from the more critical anthropology of development).

Development

Anthropology of development tends to view development from a critical perspective. The kind of issues addressed and implications for the approach involve pondering why, if a key development goal is to alleviate poverty, is poverty increasing? Why is there such a gap between plans and outcomes? Why are those working in development so willing to disregard history and the lessons it might offer? Why is development so externally driven rather than having an internal basis? In short, why does so much planned development fail?

Kinship, feminism, gender and sexuality

| Part of a series on the |

| Anthropology of kinship |

|---|

|

|

Social anthropology Cultural anthropology |

Kinship

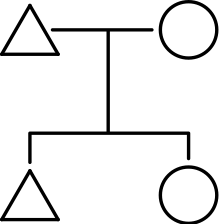

Kinship can refer both to the study of the patterns of social relationships in one or more human cultures, or it can refer to the patterns of social relationships themselves. Over its history, anthropology has developed a number of related concepts and terms, such as "descent", "descent groups", "lineages", "affines", "cognates", and even "fictive kinship". Broadly, kinship patterns may be considered to include people related both by descent (one's social relations during development), and also relatives by marriage. Within kinship you have two different families. People have their biological families and it is the people they share DNA with. This is called consanguinity or "blood ties".[52] People can also have a chosen family in which they chose who they want to be a part of their family. In some cases, people are closer with their chosen family more than with their biological families.[53]

Feminist

Feminist anthropology is a four field approach to anthropology (archeological, biological, cultural, linguistic) that seeks to reduce male bias in research findings, anthropological hiring practices, and the scholarly production of knowledge. Anthropology engages often with feminists from non-Western traditions, whose perspectives and experiences can differ from those of white feminists of Europe, America, and elsewhere. From the perspective of the Western world, historically such 'peripheral' perspectives have been ignored, observed only from an outsider perspective, and regarded as less-valid or less-important than knowledge from the Western world. Exploring and addressing that double bias against women from marginalized racial or ethnic groups is of particular interest in intersectional feminist anthropology.

Feminist anthropologists have stated that their publications have contributed to anthropology, along the way correcting against the systemic biases beginning with the "patriarchal origins of anthropology (and (academia)" and note that from 1891 to 1930 doctorates in anthropology went to males more than 85%, more than 81% were under 35, and only 7.2% to anyone over 40 years old, thus reflecting an age gap in the pursuit of anthropology by first-wave feminists until later in life.[54] This correction of systemic bias may include mainstream feminist theory, history, linguistics, archaeology, and anthropology. Feminist anthropologists are often concerned with the construction of gender across societies. Gender constructs are of particular interest when studying sexism.

According to St. Clair Drake, Vera Mae Green was, until "[w]ell into the 1960s", the only African American female anthropologist who was also a Caribbeanist. She studied ethnic and family relations in the Caribbean as well as the United States, and thereby tried to improve the way black life, experiences, and culture were studied.[55] However, Zora Neale Hurston, although often primarily considered to be a literary author, was trained in anthropology by Franz Boas, and published Tell my Horse about her "anthropological observations" of voodoo in the Caribbean (1938).[56]

Feminist anthropology is inclusive of the anthropology of birth[57] as a specialization, which is the anthropological study of pregnancy and childbirth within cultures and societies.

Medical, nutritional, psychological, cognitive and transpersonal

| Part of a series on |

| Medical and psychological anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Medical

Medical anthropology is an interdisciplinary field which studies "human health and disease, health care systems, and biocultural adaptation".[58] It is believed that William Caudell was the first to discover the field of medical anthropology. Currently, research in medical anthropology is one of the main growth areas in the field of anthropology as a whole. It focuses on the following six basic fields:[59]

- The development of systems of medical knowledge and medical care

- The patient-physician relationship

- The integration of alternative medical systems in culturally diverse environments

- The interaction of social, environmental and biological factors which influence health and illness both in the individual and the community as a whole

- The critical analysis of interaction between psychiatric services and migrant populations ("critical ethnopsychiatry": Beneduce 2004, 2007)

- The impact of biomedicine and biomedical technologies in non-Western settings

Other subjects that have become central to medical anthropology worldwide are violence and social suffering (Farmer, 1999, 2003; Beneduce, 2010) as well as other issues that involve physical and psychological harm and suffering that are not a result of illness. On the other hand, there are fields that intersect with medical anthropology in terms of research methodology and theoretical production, such as cultural psychiatry and transcultural psychiatry or ethnopsychiatry.

Nutritional

Nutritional anthropology is a synthetic concept that deals with the interplay between economic systems, nutritional status and food security, and how changes in the former affect the latter. If economic and environmental changes in a community affect access to food, food security, and dietary health, then this interplay between culture and biology is in turn connected to broader historical and economic trends associated with globalization. Nutritional status affects overall health status, work performance potential, and the overall potential for economic development (either in terms of human development or traditional western models) for any given group of people.

Psychological

Psychological anthropology is an interdisciplinary subfield of anthropology that studies the interaction of cultural and mental processes. This subfield tends to focus on ways in which humans' development and enculturation within a particular cultural group – with its own history, language, practices, and conceptual categories – shape processes of human cognition, emotion, perception, motivation, and mental health.[60] It also examines how the understanding of cognition, emotion, motivation, and similar psychological processes inform or constrain our models of cultural and social processes.[61][62]

Cognitive

Cognitive anthropology seeks to explain patterns of shared knowledge, cultural innovation, and transmission over time and space using the methods and theories of the cognitive sciences (especially experimental psychology and evolutionary biology) often through close collaboration with historians, ethnographers, archaeologists, linguists, musicologists and other specialists engaged in the description and interpretation of cultural forms. Cognitive anthropology is concerned with what people from different groups know and how that implicit knowledge changes the way people perceive and relate to the world around them.[61]

Transpersonal

Transpersonal anthropology studies the relationship between altered states of consciousness and culture. As with transpersonal psychology, the field is much concerned with altered states of consciousness (ASC) and transpersonal experience. However, the field differs from mainstream transpersonal psychology in taking more cognizance of cross-cultural issues – for instance, the roles of myth, ritual, diet, and text in evoking and interpreting extraordinary experiences.[63][64]

Political and legal

| Part of a series on |

| Political and legal anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Political

Political anthropology concerns the structure of political systems, looked at from the basis of the structure of societies. Political anthropology developed as a discipline concerned primarily with politics in stateless societies, a new development started from the 1960s, and is still unfolding: anthropologists started increasingly to study more "complex" social settings in which the presence of states, bureaucracies and markets entered both ethnographic accounts and analysis of local phenomena. The turn towards complex societies meant that political themes were taken up at two main levels. Firstly, anthropologists continued to study political organization and political phenomena that lay outside the state-regulated sphere (as in patron-client relations or tribal political organization). Secondly, anthropologists slowly started to develop a disciplinary concern with states and their institutions (and on the relationship between formal and informal political institutions). An anthropology of the state developed, and it is a most thriving field today. Geertz's comparative work on "Negara", the Balinese state, is an early, famous example.

Legal

Legal anthropology or anthropology of law specializes in "the cross-cultural study of social ordering".[65] Earlier legal anthropological research often focused more narrowly on conflict management, crime, sanctions, or formal regulation. More recent applications include issues such as human rights, legal pluralism,[66] and political uprisings.

Public

Public anthropology was created by Robert Borofsky, a professor at Hawaii Pacific University, to "demonstrate the ability of anthropology and anthropologists to effectively address problems beyond the discipline – illuminating larger social issues of our times as well as encouraging broad, public conversations about them with the explicit goal of fostering social change".[67]

Nature, science, and technology

| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of nature, science and technology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Cyborg

Cyborg anthropology originated as a sub-focus group within the American Anthropological Association's annual meeting in 1993. The sub-group was very closely related to STS and the Society for the Social Studies of Science.[68] Donna Haraway's 1985 Cyborg Manifesto could be considered the founding document of cyborg anthropology by first exploring the philosophical and sociological ramifications of the term. Cyborg anthropology studies humankind and its relations with the technological systems it has built, specifically modern technological systems that have reflexively shaped notions of what it means to be human beings.

Digital

Digital anthropology is the study of the relationship between humans and digital-era technology and extends to various areas where anthropology and technology intersect. It is sometimes grouped with sociocultural anthropology, and sometimes considered part of material culture. The field is new, and thus has a variety of names with a variety of emphases. These include techno-anthropology,[69] digital ethnography, cyberanthropology,[70] and virtual anthropology.[71]

Ecological

Ecological anthropology is defined as the "study of cultural adaptations to environments".[72] The sub-field is also defined as, "the study of relationships between a population of humans and their biophysical environment".[73] The focus of its research concerns "how cultural beliefs and practices helped human populations adapt to their environments, and how their environments change across space and time.[74] The contemporary perspective of environmental anthropology, and arguably at least the backdrop, if not the focus of most of the ethnographies and cultural fieldworks of today, is political ecology. Many characterize this new perspective as more informed with culture, politics and power, globalization, localized issues, century anthropology and more.[75] The focus and data interpretation is often used for arguments for/against or creation of policy, and to prevent corporate exploitation and damage of land. Often, the observer has become an active part of the struggle either directly (organizing, participation) or indirectly (articles, documentaries, books, ethnographies). Such is the case with environmental justice advocate Melissa Checker and her relationship with the people of Hyde Park.[76]

Environment

Social sciences, like anthropology, can provide interdisciplinary approaches to the environment. Professor Kay Milton, Director of the Anthropology research network in the School of History and Anthropology,[77] describes anthropology as distinctive, with its most distinguishing feature being its interest in non-industrial indigenous and traditional societies. Anthropological theory is distinct because of the consistent presence of the concept of culture; not an exclusive topic but a central position in the study and a deep concern with the human condition. Milton describes three trends that are causing a fundamental shift in what characterizes anthropology: dissatisfaction with the cultural relativist perspective, reaction against cartesian dualisms which obstructs progress in theory (nature culture divide), and finally an increased attention to globalization (transcending the barriers or time/space).

Environmental discourse appears to be characterized by a high degree of globalization. (The troubling problem is borrowing non-indigenous practices and creating standards, concepts, philosophies and practices in western countries.) Anthropology and environmental discourse now have become a distinct position in anthropology as a discipline. Knowledge about diversities in human culture can be important in addressing environmental problems - anthropology is now a study of human ecology. Human activity is the most important agent in creating environmental change, a study commonly found in human ecology which can claim a central place in how environmental problems are examined and addressed. Other ways anthropology contributes to environmental discourse is by being theorists and analysts, or by refinement of definitions to become more neutral/universal, etc. In exploring environmentalism - the term typically refers to a concern that the environment should be protected, particularly from the harmful effects of human activities. Environmentalism itself can be expressed in many ways. Anthropologists can open the doors of environmentalism by looking beyond industrial society, understanding the opposition between industrial and non-industrial relationships, knowing what ecosystem people and biosphere people are and are affected by, dependent and independent variables, "primitive" ecological wisdom, diverse environments, resource management, diverse cultural traditions, and knowing that environmentalism is a part of culture.[78]

Historical

Ethnohistory is the study of ethnographic cultures and indigenous customs by examining historical records. It is also the study of the history of various ethnic groups that may or may not exist today. Ethnohistory uses both historical and ethnographic data as its foundation. Its historical methods and materials go beyond the standard use of documents and manuscripts. Practitioners recognize the utility of such source material as maps, music, paintings, photography, folklore, oral tradition, site exploration, archaeological materials, museum collections, enduring customs, language, and place names.[79]

Religion

| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of religion |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

The anthropology of religion involves the study of religious institutions in relation to other social institutions, and the comparison of religious beliefs and practices across cultures. Modern anthropology assumes that there is complete continuity between magical thinking and religion,[80][n 6] and that every religion is a cultural product, created by the human community that worships it.[81]

Urban

Urban anthropology is concerned with issues of urbanization, poverty, and neoliberalism. Ulf Hannerz quotes a 1960s remark that traditional anthropologists were "a notoriously agoraphobic lot, anti-urban by definition". Various social processes in the Western World as well as in the "Third World" (the latter being the habitual focus of attention of anthropologists) brought the attention of "specialists in 'other cultures'" closer to their homes.[82] There are two main approaches to urban anthropology: examining the types of cities or examining the social issues within the cities. These two methods are overlapping and dependent of each other. By defining different types of cities, one would use social factors as well as economic and political factors to categorize the cities. By directly looking at the different social issues, one would also be studying how they affect the dynamic of the city.[83]

Key topics by field: archaeological and biological

Anthrozoology

Anthrozoology (also known as "human–animal studies") is the study of interaction between living things. It is an interdisciplinary field that overlaps with a number of other disciplines, including anthropology, ethology, medicine, psychology, veterinary medicine and zoology. A major focus of anthrozoologic research is the quantifying of the positive effects of human-animal relationships on either party and the study of their interactions.[84] It includes scholars from a diverse range of fields, including anthropology, sociology, biology, and philosophy.[85][86][n 7]

Biocultural

Biocultural anthropology is the scientific exploration of the relationships between human biology and culture. Physical anthropologists throughout the first half of the 20th century viewed this relationship from a racial perspective; that is, from the assumption that typological human biological differences lead to cultural differences.[87] After World War II the emphasis began to shift toward an effort to explore the role culture plays in shaping human biology.

Evolutionary

Evolutionary anthropology is the interdisciplinary study of the evolution of human physiology and human behaviour and the relation between hominins and non-hominin primates. Evolutionary anthropology is based in natural science and social science, combining the human development with socioeconomic factors. Evolutionary anthropology is concerned with both biological and cultural evolution of humans, past and present. It is based on a scientific approach, and brings together fields such as archaeology, behavioral ecology, psychology, primatology, and genetics. It is a dynamic and interdisciplinary field, drawing on many lines of evidence to understand the human experience, past and present.

Forensic

Forensic anthropology is the application of the science of physical anthropology and human osteology in a legal setting, most often in criminal cases where the victim's remains are in the advanced stages of decomposition. A forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification of deceased individuals whose remains are decomposed, burned, mutilated or otherwise unrecognizable. The adjective "forensic" refers to the application of this subfield of science to a court of law.

Palaeoanthropology

Paleoanthropology combines the disciplines of paleontology and physical anthropology. It is the study of ancient humans, as found in fossil hominid evidence such as petrifacted bones and footprints. Genetics and morphology of specimens are crucially important to this field.[88] Markers on specimens, such as enamel fractures and dental decay on teeth, can also give insight into the behaviour and diet of past populations.[89]

Organizations

Contemporary anthropology is an established science with academic departments at most universities and colleges. The single largest organization of anthropologists is the American Anthropological Association (AAA), which was founded in 1903.[90] Its members are anthropologists from around the globe.[91]

In 1989, a group of European and American scholars in the field of anthropology established the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) which serves as a major professional organization for anthropologists working in Europe. The EASA seeks to advance the status of anthropology in Europe and to increase visibility of marginalized anthropological traditions and thereby contribute to the project of a global anthropology or world anthropology.

Hundreds of other organizations exist in the various sub-fields of anthropology, sometimes divided up by nation or region, and many anthropologists work with collaborators in other disciplines, such as geology, physics, zoology, paleontology, anatomy, music theory, art history, sociology and so on, belonging to professional societies in those disciplines as well.[92][93]

List of major organizations

- American Anthropological Association

- American Ethnological Society

- Asociación de Antropólogos Iberoamericanos en Red, AIBR

- Anthropological Society of London

- Center for World Indigenous Studies

- Ethnological Society of London

- European Association of Social Anthropologists

- Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

- Network of Concerned Anthropologists

- N.N. Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology

- Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland

- Society for Anthropological Sciences

- Society for Applied Anthropology

- USC Center for Visual Anthropology

Ethics

As the field has matured it has debated and arrived at ethical principles aimed at protecting both the subjects of anthropological research as well as the researchers themselves, and professional societies have generated codes of ethics.[94]

Anthropologists, like other researchers (especially historians and scientists engaged in field research), have over time assisted state policies and projects, especially colonialism.[95][96]

Some commentators have contended:

- That the discipline grew out of colonialism, perhaps was in league with it, and derives some of its key notions from it, consciously or not. (See, for example, Gough, Pels and Salemink, but cf. Lewis 2004).[97]

- That ethnographic work is often ahistorical, writing about people as if they were "out of time" in an "ethnographic present" (Johannes Fabian, Time and Its Other).

- In his article "The Misrepresentation of Anthropology and Its Consequence", Herbert S. Lewis critiqued older anthropological works that presented other cultures as if they were strange and unusual. While the findings of those researchers should not be discarded, the field should learn from its mistakes.[98]

Cultural relativism

As part of their quest for scientific objectivity, present-day anthropologists typically urge cultural relativism, which has an influence on all the sub-fields of anthropology.[24] This is the notion that cultures should not be judged by another's values or viewpoints, but be examined dispassionately on their own terms. There should be no notions, in good anthropology, of one culture being better or worse than another culture.[99][100]

Ethical commitments in anthropology include noticing and documenting genocide, infanticide, racism, sexism, mutilation (including circumcision and subincision), and torture. Topics like racism, slavery, and human sacrifice attract anthropological attention and theories ranging from nutritional deficiencies,[101] to genes,[102] to acculturation, to colonialism, have been proposed to explain their origins and continued recurrences.

To illustrate the depth of an anthropological approach, one can take just one of these topics, such as "racism" and find thousands of anthropological references, stretching across all the major and minor sub-fields.[103][104][105][106]

Military involvement

Anthropologists' involvement with the U.S. government, in particular, has caused bitter controversy within the discipline. Franz Boas publicly objected to US participation in World War I, and after the war he published a brief exposé and condemnation of the participation of several American archaeologists in espionage in Mexico under their cover as scientists.[107]

But by the 1940s, many of Boas' anthropologist contemporaries were active in the allied war effort against the Axis Powers (Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan). Many served in the armed forces, while others worked in intelligence (for example, Office of Strategic Services and the Office of War Information). At the same time, David H. Price's work on American anthropology during the Cold War provides detailed accounts of the pursuit and dismissal of several anthropologists from their jobs for communist sympathies.[108]

Attempts to accuse anthropologists of complicity with the CIA and government intelligence activities during the Vietnam War years have turned up little. Many anthropologists (students and teachers) were active in the antiwar movement. Numerous resolutions condemning the war in all its aspects were passed overwhelmingly at the annual meetings of the American Anthropological Association (AAA).[109]

Professional anthropological bodies often object to the use of anthropology for the benefit of the state. Their codes of ethics or statements may proscribe anthropologists from giving secret briefings. The Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth (ASA) has called certain scholarship ethically dangerous. The "Principles of Professional Responsibility" issued by the American Anthropological Association and amended through November 1986 stated that "in relation with their own government and with host governments ... no secret research, no secret reports or debriefings of any kind should be agreed to or given."[110] The current "Principles of Professional Responsibility" does not make explicit mention of ethics surrounding state interactions.[111]

Anthropologists, along with other social scientists, are working with the US military as part of the US Army's strategy in Afghanistan.[112] The Christian Science Monitor reports that "Counterinsurgency efforts focus on better grasping and meeting local needs" in Afghanistan, under the Human Terrain System (HTS) program; in addition, HTS teams are working with the US military in Iraq.[113] In 2009, the American Anthropological Association's Commission on the Engagement of Anthropology with the US Security and Intelligence Communities (CEAUSSIC) released its final report concluding, in part, that:

When ethnographic investigation is determined by military missions, not subject to external review, where data collection occurs in the context of war, integrated into the goals of counterinsurgency, and in a potentially coercive environment – all characteristic factors of the HTS concept and its application – it can no longer be considered a legitimate professional exercise of anthropology. In summary, while we stress that constructive engagement between anthropology and the military is possible, CEAUSSIC suggests that the AAA emphasize the incompatibility of HTS with disciplinary ethics and practice for job seekers and that it further recognize the problem of allowing HTS to define the meaning of 'anthropology' within DoD.[114]

Post-World War II developments

Before WWII British 'social anthropology' and American 'cultural anthropology' were still distinct traditions. After the war, enough British and American anthropologists borrowed ideas and methodological approaches from one another that some began to speak of them collectively as 'sociocultural' anthropology.

Basic trends

There are several characteristics that tend to unite anthropological work. One of the central characteristics is that anthropology tends to provide a comparatively more holistic account of phenomena and tends to be highly empirical.[23] The quest for holism leads most anthropologists to study a particular place, problem or phenomenon in detail, using a variety of methods, over a more extensive period than normal in many parts of academia.

In the 1990s and 2000s, calls for clarification of what constitutes a culture, of how an observer knows where his or her own culture ends and another begins, and other crucial topics in writing anthropology were heard. These dynamic relationships, between what can be observed on the ground, as opposed to what can be observed by compiling many local observations remain fundamental in any kind of anthropology, whether cultural, biological, linguistic or archaeological.[115][116]

Biological anthropologists are interested in both human variation[117][118] and in the possibility of human universals (behaviors, ideas or concepts shared by virtually all human cultures).[119][120] They use many different methods of study, but modern population genetics, participant observation and other techniques often take anthropologists "into the field," which means traveling to a community in its own setting, to do something called "fieldwork." On the biological or physical side, human measurements, genetic samples, nutritional data may be gathered and published as articles or monographs.

Along with dividing up their project by theoretical emphasis, anthropologists typically divide the world up into relevant time periods and geographic regions. Human time on Earth is divided up into relevant cultural traditions based on material, such as the Paleolithic and the Neolithic, of particular use in archaeology. Further cultural subdivisions according to tool types, such as Olduwan or Mousterian or Levalloisian help archaeologists and other anthropologists in understanding major trends in the human past. Anthropologists and geographers share approaches to culture regions as well, since mapping cultures is central to both sciences. By making comparisons across cultural traditions (time-based) and cultural regions (space-based), anthropologists have developed various kinds of comparative method, a central part of their science.

Commonalities between fields

Because anthropology developed from so many different enterprises (see History of anthropology), including but not limited to fossil-hunting, exploring, documentary film-making, paleontology, primatology, antiquity dealings and curatorship, philology, etymology, genetics, regional analysis, ethnology, history, philosophy, and religious studies,[121][122] it is difficult to characterize the entire field in a brief article, although attempts to write histories of the entire field have been made.[123]

Some authors argue that anthropology originated and developed as the study of "other cultures", both in terms of time (past societies) and space (non-European/non-Western societies).[124] For example, the classic of urban anthropology, Ulf Hannerz in the introduction to his seminal Exploring the City: Inquiries Toward an Urban Anthropology mentions that the "Third World" had habitually received most of attention; anthropologists who traditionally specialized in "other cultures" looked for them far away and started to look "across the tracks" only in late 1960s.[82]

Now there exist many works focusing on peoples and topics very close to the author's "home".[125] It is also argued that other fields of study, like History and Sociology, on the contrary focus disproportionately on the West.[126]

In France, the study of Western societies has been traditionally left to sociologists, but this is increasingly changing,[127] starting in the 1970s from scholars like Isac Chiva and journals like Terrain ("fieldwork") and developing with the center founded by Marc Augé (Le Centre d'anthropologie des mondes contemporains, the Anthropological Research Center of Contemporary Societies).

Since the 1980s it has become common for social and cultural anthropologists to set ethnographic research in the North Atlantic region, frequently examining the connections between locations rather than limiting research to a single locale. There has also been a related shift toward broadening the focus beyond the daily life of ordinary people; increasingly, research is set in settings such as scientific laboratories, social movements, governmental and nongovernmental organizations and businesses.[128]

See also

- Anthropological science fiction

- Christian anthropology, a sub-field of theology

- Circumscription theory – Political theory

- Culture – Social behavior and norms of a society

- Dual inheritance theory – Theory of human behavior

- Emic and etic – Two kinds of anthropologic field research

- Engaged theory – Comprehensive Critical Theory

- Ethnobiology – Study of how living things are used by human cultures

- Human behavioral ecology – Study of human behavior and cultural diversity

- Human ethology – The study of human behavior

- Human Relations Area Files – International nonprofit membership organization

- Intangible cultural heritage – Class of UNESCO designated cultural heritage

- Origins of society – topic within evolutionary biology, anthropology, prehistory and palaeolithic archaeology

- Philosophical anthropology, a sub-field of philosophy

- Prehistoric medicine – Medicine in the time before the invention of writing

- Qualitative research – Form of research

Lists

- Outline of anthropology – Overview of and topical guide to anthropology

- List of indigenous peoples

- List of anthropologists

Notes

- ↑ Richard Harvey's 1593 Philadelphus, a defense of the legend of Brutus in British history, includes the passage "Genealogy or issue which they had, Artes which they studied, Actes which they did. This part of History is named Anthropology."

- ↑ John Kersey's 1706 edition of The New World of English Words includes the definition "Anthropology, a Discourse or Description of Man, or of a Man's Body."

- ↑ In French: L'Anthropologie, c'est à dire la science qui traite de l'homme, est divisée ordinairment & avec raison en l'Anatomie, qui considere le corps & les parties, et en la Psychologie, qui parle de l'Ame.[11]

- ↑ As Fletcher points out, the French society was by no means the first to include anthropology or parts of it as its topic. Previous organizations used other names. The German Anthropological Association of St. Petersburg, however, met first in 1861, but due to the death of its founder never met again.[15]

- ↑ Hunt's choice of theorists does not exclude the numerous other theorists that were beginning to publish a large volume of anthropological studies.[20]

- ↑ "It seems to be one of the postulates of modern anthropology that there is complete continuity between magic and religion. [note 35: See, for instance, RR Marett, Faith, Hope, and Charity in Primitive Religion, the Gifford Lectures (Macmillan, 1932), Lecture II, pp. 21 ff.] ... We have no empirical evidence at all that there ever was an age of magic that has been followed and superseded by an age of religion."[80]

- ↑ Anthrozoology should not be confused with "animal studies", which often refers to animal testing.

References

- 1 2 3 "anthropology". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 "anthropology". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 "What is Anthropology?". American Anthropological Association. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Sociocultural Anthropology and Ethnography | Department of Anthropology". Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ↑ "Archaeological Anthropology". UAPress. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ↑ "Archaeological Anthropology". Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ↑ "Paleoanthropology | Britannica".

- 1 2 3 4 Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "anthropology, n." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1885.

- ↑ Israel Institute of the History of Medicine (1952). Koroth. Brill. p. 19. GGKEY:34XGYHLZ7XY. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Burkhart, Louise M. (2003). "Bernardino de Sahagun: First Anthropologist (review)". The Catholic Historical Review. 89 (2): 351–352. doi:10.1353/cat.2003.0100. S2CID 162350550.

- 1 2 Bartholin, Caspar; Bartholin, Thomas (1647). "Preface". Institutions anatomiques de Gaspar Bartholin, augmentées et enrichies pour la seconde fois tant des opinions et observations nouvelles des modernes. Translated from the Latin by Abr. Du Prat. Paris: M. Hénault et J. Hénault.

- ↑ Sibeud, Emmanuelle (2008). "The Metamorphosis of Ethnology in France, 1839–1930". In Kuklick, Henrika (ed.). A New History of Anthropology. Blackwell Publishing. p. 98. ISBN 9780470766217.

- ↑ Schiller 1979, pp. 130–132

- ↑ Schiller 1979, p. 221

- 1 2 Fletcher, Robert (1882). "Paul Broca and the French School of Anthropology". The Saturday Lectures, Delivered in the Lecture-room of the U. S. National Museum under the Auspices of the Anthropological and Biological Societies of Washington in March and April 1882. Boston; Washington, DC: D. Lothrop & Co.; Judd & Detweiler.

- ↑ Schiller 1979, p. 143

- ↑ Schiller 1979, p. 136

- ↑ Waitz 1863, p. 5

- ↑ Waitz 1863, pp. 11–12

- 1 2 Hunt 1863, Introductory Address

- ↑ Maccurdy, George Grant (1899). "Extent of Instruction in Anthropology in Europe and the United States". Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. 10 (260): 382–390. Bibcode:1899Sci....10..910M. doi:10.1126/science.10.260.910. PMID 17837336.

- ↑ "Home". World Council of Anthropological Associations. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- 1 2 Hylland Eriksen, Thomas. (2004) "What is Anthropology" Pluto. London. p. 79. ISBN 0-7453-2320-0.

- 1 2 3 Ingold, Tim (1994). "Introduction to culture". Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-415-02137-1.

- ↑ On varieties of cultural relativism in anthropology, see Spiro, Melford E. (1987) "Some Reflections on Cultural Determinism and Relativism with Special Reference to Emotion and Reason," in Culture and Human Nature: Theoretical Papers of Melford E. Spiro. Edited by B. Kilborne and L.L. Langness, pp. 32–58. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Heyck, Thomas William; Stocking, George W.; Goody, Jack (1997). "After Tylor: British Social Anthropology 1888–1951". The American Historical Review. 102 (5): 1486–1488. doi:10.2307/2171126. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 2171126.

- ↑ "What is Anthropology?".

- ↑ Layton, Robert (1998) An Introduction to Theory in Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ What is Anthropology – American Anthropological Association Archived 15 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Aaanet.org. Retrieved on 2 November 2016.

- ↑ What is Anthropology Archived 10 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Living Anthropologically. Retrieved on 2017-17-01.

- ↑ Ahmed, Akbar S. (1984). "Al-Beruni: The First Anthropologist". RAIN. 60 (60): 9–10. doi:10.2307/3033407. JSTOR 3033407.

- ↑ Understanding Other Religions: Al-Biruni's and Gadamer's "fusion of Horizons" By Kemal Ataman p. 59

- ↑ Bloch, Maurice (1991). "Language, Anthropology and Cognitive Science". Man. 26 (2): 183–198. doi:10.2307/2803828. JSTOR 2803828.

- ↑ Daniel A. Segal; Sylvia J. Yanagisako, eds. (2005). Unwrapping the Sacred Bundle. Durham and London: Duke University Press. pp. Back Cover. ISBN 978-0-8223-8684-1.

- 1 2 Ingold, Tim (1994). "General Introduction". Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Taylor & Francis. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-415-02137-1.

- ↑ Tim Ingold (1996). Key Debates in Anthropology. p. 18.

the traditional anthropological project of cross-cultural or cross-societal comparison

- ↑ Bernard, H. Russell (2002). Research Methods in Anthropology (PDF). Altamira Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-7591-0868-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2016.

- ↑ George Peter Murdock; Douglas R. White (1969). "Standard Cross-Cultural Sample". Ethnology. 9: 329–369. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ "Research Subfields: Physical or Biological". University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Robbins, R.H. & Larkin, S.N. (2007). Cultural Anthropology: A problem-based approach. Toronto, ON: Nelson Education Ltd.

- ↑ "What is Anthropology? – Advance Your Career". www.americananthro.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ↑ Salzmann, Zdeněk. (1993) Language, culture, and society: an introduction to linguistic anthropology. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- ↑ Atkinson, Paul; Coffey, Amanda; Delamont, Sara; Lofland, Lyn; Lofland, John; Lofland, Professor Lyn H. (2001). Handbook of Ethnography. Sage. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7619-5824-6.

- ↑ Ingold, Timothy (2008). "Anthropology is not ethnography". Proceedings of the British Academy. 154: 69–92. ISSN 0068-1202.

- ↑ Layton, Robert. (1981) The Anthropology of Art.

- ↑ Spitulnik, Deborah (1993). "Anthropology and Mass Media" (PDF). Annual Review of Anthropology. 22: 293. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.22.100193.001453. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "Ethnomusicology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ Hann, Chris; Hart, Keith (2011). Economic Anthropology. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 55–71. ISBN 978-0-7456-4482-0.

- ↑ Heffernan, Timothy (2022). Economic Anthropology in View of the Global Financial Crisis, in The Palgrave Handbook of the History of Human Sciences. Singapore: Springer Nature. pp. 457–481. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-7255-2_14.

- ↑ Roseberry, William (1988). "Political Economy". Annual Review of Anthropology. 17: 161–185. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.17.100188.001113.

- ↑ Kedia, Satish, and Willigen J. Van (2005). Applied Anthropology: Domains of Application. Westport, Conn: Praeger. pp. 16, 150. ISBN 978-0-275-97841-9.

- ↑ "Types of Kinship- Consanguineal and Affinal" (PDF). inflibnet.ac.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ↑ Pountney, Laura (2015). Introducing anthropology. Maric, Tomislav. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-9977-6. OCLC 909318382.

- ↑ Cattell, Maria and Marjorie M. Schweitzer, editors. Women in Anthropology: Autobiographical Narratives and Social History. (Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek), pp. 15–40. ISBN 1-59874-083-0

- ↑ Cole, Johnnetta B. (September 1982). "Vera Mae Green, 1928–1982". American Anthropologist. 84 (3): 633–635. doi:10.1525/aa.1982.84.3.02a00080.

- ↑ Trefzer, Annette (28 November 2023). "Possessing the Self: Caribbean Identities in Zora Neale Hurston's Tell My Horse". African American Review. 34 (2): 299–312. doi:10.2307/2901255. JSTOR 2901255.

- ↑ Sargent, Carolyn (2004). "Birth". Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology. pp. 224–230. doi:10.1007/0-387-29905-X_26. ISBN 978-0-306-47754-6.

- ↑ McElroy, A (1996). "Medical Anthropology" (PDF). In D. Levinson; M. Ember (eds.). Encyclopedia of Cultural Anthropology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ↑ Campbell, Dave (24 October 2016). "Anthropology's Contribution to Public Health Policy Development". McGill Journal of Medicine. 13 (1): 76. ISSN 1201-026X. PMC 3277334. PMID 22363184.

- ↑ LeVine, R. A., Norman, K. (2001). "The infant's acquisition of culture: Early attachment reexamined in anthropological perspective". Publications – Society for Psychological Anthropology. 12: 83–104.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 D'Andrade, R. (1999). "The Sad Story of Anthropology: 1950–1999". In Cerroni-Long, E.L. (ed.). Anthropological Theory in North America. Westport: Berin & Garvey. ISBN 978-0-89789-685-6.

- ↑ Schwartz, T.; G.M. White; et al., eds. (1992). New Directions in Psychological Anthropology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Schroll, M. A., & Schwartz, S. A. (2005). "Whither Psi and Anthropology? An Incomplete History of SAC's Origins, Its Relationship with Transpersonal Psychology and the Untold Stories of Castaneda's Controversy". Anthropology of Consciousness. 16: 6–24. doi:10.1525/ac.2005.16.1.6.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Young, David E.; Goulet, J.G. (1994). Being Changed by Cross-cultural Encounters: The Anthropology of Extraordinary Experiences. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Carol J. (1986). Praying for Justice: Faith, Order, and Community in an American Town. Ithaca: Cornell UP. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8014-1971-3.

- ↑ Hent de Vries; Lawrence E. Sullivan, eds. (2006). Political theologies: public religions in a post-secular world. New York: Fordham University Press.

- ↑ "Center for a Public Anthropology". Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ↑ Dumit, Joseph. Davis-Floyd, Robbie (2001). "Cyborg Anthropology". in Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92092-2.

- ↑ "Techno-Anthropology course guide". Aalborg University. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ↑ Knorr, Alexander (2011). Cyberanthropology. Peter Hammer Verlag Gmbh. ISBN 978-3-7795-0359-0. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ↑ Weber, Gerhard; Bookstein, Fred (2011). Virtual Anthropology: A guide to a new interdisciplinary field. Springer. ISBN 978-3-211-48647-4.

- ↑ Kottak, Conrad Phillip (2010). Anthropology : appreciating human diversity (14th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 579–584. ISBN 978-0-07-811699-5.

- ↑ Townsend, Patricia K. (2009). Environmental anthropology : from pigs to policies (2nd ed.). Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-57766-581-6.

- ↑ Kottak, Conrad P. (1999). "The New Ecological Anthropology". American Anthropologist. 101 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1525/aa.1999.101.1.23. hdl:2027.42/66329. JSTOR 683339. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Pyke, G H (1984). "Optimal Foraging Theory: A Critical Review". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 15: 523. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.15.110184.002515. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Melissa Checker (2005). Polluted promises: environmental racism and the search for justice in a southern town. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1657-1.

- ↑ "Milton, Kay 1951". OCLC WorldCat Identities. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ↑ Milton, Kay (1996). Environmentalism and Cultural Theory; Exploring the Role of Anthropology in Environmental Discourse. New York.: Routledge Press.

- ↑ Axtell, J. (1979). "Ethnohistory: An Historian's Viewpoint". Ethnohistory. 26 (1): 3–4. doi:10.2307/481465. JSTOR 481465.

- 1 2 Cassirer, Ernst (1944) An Essay On Man Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, pt.II, ch.7 Myth and Religion, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Guthrie (2000) Guide to the Study of Religion. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 225–226 Archived 25 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 0-304-70176-9.

- 1 2 Hannerz, Ulf (1980) Exploring the City: Inquiries Toward an Urban Anthropology, ISBN 0-231-08376-9, p. 1. Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Griffiths, M. B.; Chapman, M.; Christiansen, F. (2010). "Chinese consumers: The Romantic reappraisal". Ethnography. 11 (3): 331–357. doi:10.1177/1466138110370412. JSTOR 24047982. S2CID 144152261.

- ↑ Mills, Daniel S (2010). "Anthrozoology" Archived 3 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Encyclopedia of Applied Animal Behaviour and Welfare. CABI, pp. 28–30. ISBN 0-85199-724-4.

- ↑ DeMello, Margo (2010). Teaching the Animal: Human–Animal Studies Across the Disciplines. Lantern Books. p. xi. ISBN 1-59056-168-6

- ↑ "Animals & Society Institute". Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ Goodman, Alan H.; Leatherman, Thomas L., eds. (1998). Building A New Biocultural Synthesis. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06606-3. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ Kelso, Janet; Pääbo, Svante; Meyer, Matthias; Prüfer, Kay; Reich, David; Patterson, Nick; Slatkin, Montgomery; Nickel, Birgit; Nagel, Sarah (March 2018). "Reconstructing the genetic history of late Neanderthals" (PDF). Nature. 555 (7698): 652–656. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..652H. doi:10.1038/nature26151. hdl:1887/70268. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 6485383. PMID 29562232. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ↑ Towle, Ian; Irish, Joel D.; De Groote, Isabelle (2017). "Behavioral inferences from the high levels of dental chipping in Homo naledi". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 164 (1): 184–192. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23250. PMID 28542710. S2CID 24296825.

- ↑ AAAnet.org Archived 22 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. AAAnet.org. Retrieved on 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "American Anthropological Association – Monthly Membership Report" (PDF). 13 June 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2010.

- ↑ Johanson, Donald and Wong, Kate (2007). Lucy's Legacy. Kindle Books.

- ↑ Netti, Bruno (2005). The Study of Ethnomusicology. Ch. 1. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-03033-8.

- ↑ "Final Report of the Commission to Review the AAA Statements on Ethics – Participate & Advocate". American Anthropological Association. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ Asad, Talal, ed. (1973) Anthropology & the Colonial Encounter. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press.

- ↑ van Breman, Jan, and Akitoshi Shimizu (1999) Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press.

- ↑ Gellner, Ernest (1992) Postmodernism, Reason, and Religion Archived 3 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 26–29. ISBN 0-415-08024-X.

- ↑ Lewis, Herbert S. (1998). "The Misrepresentation of Anthropology and Its Consequences". American Anthropologist. 100 (3): 716–731. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.716. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 682051. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Levi-Strauss, Claude (1962). The Savage Mind.

- ↑ Womack, Mari (2001). Being Human.

- ↑ Harris, Marvin. Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches.

- ↑ "Is there a gene for racism?". Times Higher Education. 3 August 2007. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "Statement on "Race"". American Anthropological Association. 17 May 1998. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- ↑ Marshall, E. (1998). "Cultural Anthropology: DNA Studies Challenge the Meaning of Race". Science. 282 (5389): 654–655. Bibcode:1998Sci...282..654M. doi:10.1126/science.282.5389.654. PMID 9841421. S2CID 22257033.

- ↑ Goodman, Allan (1995). "The Problematics of "Race" in Contemporary Biological Anthropology." In Biological Anthropology: The State of the Science. International Institute for Human Evolutionary Research. ISBN 0-9644248-0-0.

- ↑ De Montellano, Bernard R. Ortiz (1993). "Melanin, afrocentricity, and pseudoscience". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 36: 33–58. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330360604. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Browman, David (22 November 2011). "Spying by American Archaeologists in World War I". Bulletin of the History of Archaeology. 21 (2): 10–17. doi:10.5334/bha.2123. ISSN 2047-6930.

- ↑ Price, David H. (1 June 1998). "Cold war anthropology: Collaborators and victims of the national security state". Identities. 4 (3–4): 389–430. doi:10.1080/1070289X.1998.9962596. ISSN 1070-289X.

- ↑ Lee, Richard Borshay (June 2016). "The anti-imperialist tradition in North American anthropology: Vietnam, the Left Academy, and the founding of ARPA". Dialectical Anthropology. 40 (2): 60. doi:10.1007/s10624-016-9412-y. JSTOR 43895186. S2CID 146855589. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ↑ "Past AAA Statements on Ethics – Participate & Advocate". www.americananthro.org. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ↑ "Ethics Forum » Full Text of the 2012 Ethics Statement". Ethics Forum. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ↑ US Army's strategy in Afghanistan: better anthropology Archived 11 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. CSMonitor.com (7 September 2007). Retrieved on 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Human Terrain System: A CORDS for the 21st Century". Archived from the original on 21 January 2014.

- ↑ AAA Commission on the Engagement of Anthropology with the US Security and Intelligence Communities (14 October 2009). Final Report on The Army's Human Terrain System Proof of Concept Program (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ↑ Rosaldo, Renato (1993). Culture and Truth: The remaking of social analysis. Beacon Press. Inda

- ↑ Xavier, John and Rosaldo, Renato (2007). The Anthropology of Globalization. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ↑ Jurmain, Robert; Kilgore, Lynn; Trevathan, Wenda and Ciochon, Russell L. (2007). Introduction to Physical Anthropology. 11th ed. Wadsworth. chapters I, III and IV. ISBN 0-495-18779-8.

- ↑ Wompack, Mari (2001). Being Human. Prentice Hall. pp. 11–20. ISBN 0-13-644071-1

- ↑ Brown, Donald (1991). Human Universals. McGraw Hill.

- ↑ Roughley, Neil (2000). Being Humans: Anthropological Universality and Particularity in Transciplinary Perspectives. Walter de Gruyter Publishing.

- ↑ Erickson, Paul A. and Liam D. Murphy (2003). A History of Anthropological Theory. Broadview Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 1-4426-0110-8.

- ↑ Stocking, George (1992) "Paradigmatic Traditions in the History of Anthropology", pp. 342–361 in George Stocking, The Ethnographer's Magic and Other Essays in the History of Anthropology. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-13414-8.

- ↑ Leaf, Murray (1979). Man, Mind and Science: A History of Anthropology. Columbia University Press.

- ↑ See the many essays relating to this in Prem Poddar and David Johnson, Historical Companion to Postcolonial Thought in English, Edinburgh University Press, 2004. See also Prem Poddar et al., Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures – Continental Europe and its Empires, Edinburgh University Press, 2008