This timeline of troodontid research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the troodontids, a group of bird-like theropod dinosaurs including animals like Troodon. Troodontid remains were among the first dinosaur fossils to be reported from North America after paleontologists began performing research on the continent, specifically the genus Troodon itself.[1] Since the type specimen of this genus was only a tooth and Troodon teeth are unusually similar to those of the unrelated thick-headed pachycephalosaurs, Troodon and its relatives would be embroiled in taxonomic confusion for over a century. Troodon was finally recognized as distinct from the pachycephalosaurs by Phil Currie in 1987. By that time many other species now recognized as troodontid had been discovered but had been classified in the family Saurornithoididae. Since these families were the same but the Troodontidae named first, it carries scientific legitimacy.[2]

Many milestones of troodontid research occurred between the description of Troodon and the resolution of their confusion with pachycephalosaurs. The family itself was named by Charles Whitney Gilmore in 1924.[2] That same year Henry Fairfield Osborn named the genus Saurornithoides.[3] In the 1960s and 1970s researchers like Russell and Hopson observed that troodontids had very large brains for their body size. Both attributed this enlargement of the brain to a need for processing the animal's especially sharp senses.[4] Also in the 1970s, Barsbold described the new species Saurornithoides (now Zanabazar) junior[3] and named the family Saurornithoidae, but as noted this was just a junior synonym of the Troodontidae in the first place.[2]

In the 1980s Gauthier classed them with the dromaeosaurids in the Deinonychosauria.[2] That same decade Jack Horner reported the discovery of Troodon nests in Montana.[5] Interest in the life history of Troodon continued in the 1990s with a study of its growth rates based on histological sections of fossils taken from a bonebed in Montana[4] and the apparent pairing of eggs in Troodon nests.[5] This decade also saw the first potential report of European troodontid remains, although this claim has been controversial.[4] A single mysterious tooth from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the United States was described as the oldest known troodontid remains, although this has also been controversial.[2] In the 2000s, several new kinds of troodontid were named, like Byronosaurus and Sinovenator.[3]

19th century

1850s

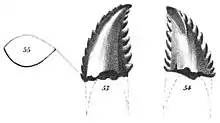

- Joseph Leidy described the new genus and species Troodon formosus based on an isolated tooth crown. It was one of the first dinosaurs from North America to be formally named, though it was believed to be a lizard until 1877.[2]

1870s

- Edward Drinker Cope described the new species Laelaps explanatus. He also described the new genus and species Paronychodon lacustris.[6]

- Cope described the new species Laelaps cristatus and L. laevifrons. He also described the new genus and species Zapsalis abradens.[6]

20th century

1900s

- Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás classified Troodon as a megalosaurid.[8]

1910s

- Roy Chapman Andrews described the new genus and species Elopteryx nopcsai.[3] Initially thought to be a bone fragment from a bird, it was later considered a troodontid, but may in fact be an alvarezsaurid.[9]

1920s

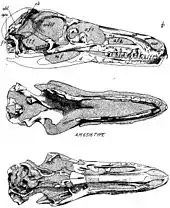

- Henry Fairfield Osborn described the first troodontid known from more than teeth; a reasonably complete skeleton and skull was placed in the new genus and species Saurornithoides mongoliensis.[3]

- Charles Whitney Gilmore named the Troodontidae. At the time the name mainly applied to taxa now considered to be pachycephalosaurs because the groups have vaguely similar teeth.[2]

1930s

- Gilmore described the new genus and species Polyodontosaurus grandis.[3]

- C.M. Sternberg described the new genus and species Stenonychosaurus inequalis.[3]

1940s

1960s

- Estes synonymized Paronychodon with the mammal Tripriodon caperatus, based on similar teeth, though this was later shown to be an error.[6]

- Russell noted the large brain to body size ratio in troodontids and hypothesized that this relatively high level of brain power was used to process its sharpened senses.[4]

1970s

- Rinchen Barsbold described the new species Saurornithoides junior[3] and named the Saurornithoididae.[2]

- Colin James Oliver Harrison and Cyril Alexander Walker described the new genus and species Bradycneme draculae.[3] They also described the new genus and species Heptasteornis andrewsi.[6] Both fragmentary fossils were at first identified as birds, and later as troodontids, though researchers currently classify them as alvarezsaurids.[11]

- James Hopson noted the large brain to body size ratio in troodontids and hypothesized that this relatively high level of brain power was used to process its sharpened senses.[4]

1980s

- Russell and Ronald Séguin interpreted troodontids as carnivores who ate small prey items like mammals, dinosaur eggs and hatchlings, as well as insects.[4]

- Halszka Osmólska disputed the idea that troodontids used the large claw on their second toe in hunting large prey because it was smaller than the equivalent claw in dromaeosaurids.[4]

- Horner reported troodontid nests from Montana.[5]

- Kenneth Carpenter described the new genus and species Pectinodon bakkeri.[3]

- Lev Nesov described the new genus and species Pectinodon asiamericanus.[6]

- Phil Currie hypothesized that troodontids' basisphenoid bullae may have helped them hear very low frequency sounds.[4]

- Jacques Gauthier classified troodontids as deinonychosaurs.[2]

- James H. Madsen described the new genus and species Borogovia gracilicrus.[3]

- Currie noted traits in the teeth of Troodon that distinguished them from those of pachycephalosaurs. He split the Troodontidae off from the latter group and noted that the family Saurornithoididae, which then classified many dinosaurs now considered troodontids, was actually it junior synonym.[2]

- Rinchen Barsbold and others described a new genus the early Cenomanian Khamareen Us site in Mongolia, however he decided not to name it because the specimen was so incomplete.[12]

1990s

- Osmólska and Barsbold reported possible troodontid remains from Europe, although without substantial evidentiary support.[2] They also published the first evolutionary tree of the Troodontids, based on changes in proportions of the second phalanx in the second toe rather than a standard cladistic character matrix. They found Troodon formosus to be the sister taxon to the genus Saurornithoides and Borogovia.[12]

- Barsbold and Osmólska disputed the idea that troodontids used the large claw on their second toe in hunting large prey because it was smaller than the equivalent claw in dromaeosaurids.[4]

- Currie and others proposed that Paronychodon teeth were not the remains of a distinct species but were actually injured, diseased, or deformed teeth belonging to many different species.[13]

- Miguel Telles Antunes and Denise Sigogneau-Russell described the new genus and species Euronychodon portucalensis.[3]

- Sergei Mikhailovich Kurzanov and Osmólska described the new genus and species Tochisaurus nemegtensis.[3]

- Russell and Dong Zhiming described the new genus and species Sinornithoides youngi.[3] They found troodontids to be the sister group of a clade containing the oviraptorosaurs and therizinosaurs.[2]

- Stafford Howse and Andrew Milner reported possible troodontid remains from Europe, although without substantial evidentiary support.[2]

- David Varricchio studied the remains of many Troodon formosus preserved in a bonebed. The co-occurrence of so many individuals of the same species preserved together suggested to him that this species may have been a social animal. Varrichio also studied histological sections of bones taken from individuals preserved in this bonebed at varying stages of growth. He found that it took less than five years for a hatchling Troodon to reach adult size, at which point it stopped growing.[4]

- Daniel Chure described the new genus and species Koparion douglassi.[6] This Late Jurassic taxon may be the oldest known troodontid, but since the type specimen consisted only of a single tooth it is impossible to know for sure if it is actually a troodontid.[2]

- Thomas Richard Holtz Jr found troodontids to be the sister group to the ornithomimosaurs in the Bullatosauria.[2]

- Holtz and others noted similarities in the teeth of troodontids and iguanine lizards and suggested that the former family may not have been strict carnivores.[4]

- Nesov described the new species Euronychodon asiaticus.[3] He also described the new species Troodon isfarensis.[6]

- Nesov described the new species Troodon asiamericanus.[6]

- Darla Zelenitsky and Leonard Hills described the eggs of Troodon formosus. They found that the surface of Troodon eggs were smooth and their pores occurred singly or in pairs. When viewed in thin section, the eggshell exhibited two distinct layers. The inner layer was composed of blocky calcite crystals while crystals composing the outer layer were prismatic. Similar eggs in the past had been attributed to primitive ornithopods and relatives of Protoceratops but were actually laid by theropods.[5]

- Paul Callistus Sereno classified troodontids as deinonychosaurs.[2]

- Richard Ciffeli and others reported possible troodontid teeth from a Cenomanian-aged microvertebrate fossil site in Utah. The teeth are similar to those referred to the controversial genus Paronychodon. If these fossils really are troodontid, they might well be the oldest known occurrence of the family in North America.[13]

- Varricchio and others published a detailed study of troodontid nests from Montana. The eggs were laid in a tight circular formation with the narrow end pointed down. Although the eggs were at least partially covered by sediment the nest itself was basically open. Since one nest preserved a partial adult skeleton, the researchers concluded that these troodontids may have brooded their eggs like modern birds. The researchers also subjected the positions of individual eggs to statistical analysis and found that the eggs seemed to cluster in pairs. This is evidence that these dinosaurs had two functioning oviducts. Varrichio and the other researchers also noted that the ratio between the size of the egg and the body of the mother in these troodontids were between those of modern crocodiles and birds.[5]

- Peter Makovicky and Hans-Dieter Sues classified troodontids as deinonychosaurs.[2]

- Holtz and others noted similarities in the teeth of troodontids and iguanine lizards and suggested that the former family may not have been strict carnivores.[4]

- Holtz found that troodontids were the sister group to the ornithomimosaurs.[2]

- Catherine Forster and others found that troodontids were the sister group of the avialans.[2]

- Sereno defined the Troodontidae as all taxa more closely related to Troodon formosus than to Velociraptor mongoliensis.[14]

- Fernando Emilio Novas and others reported a possible troodontid specimen from Coniacian to Turonian-aged sediments in South America. If this report is accurate it suggests that after first evolving in Asia, troodontids dispersed into North America and then traveled further down to South America.[13]

- Sereno classified troodontids as deinonychosaurs.[2]

21st century

2000s

- Mark Norell, Makovicky and Clark described the new genus and species Byronosaurus jaffei.[3] They performed a cladistic analysis of the troodontids based on 38 characters in 10 taxa. Norell and others found troodontids to be the sister group of a clade containing the oviraptorosaurs and therizinosaurs. They found Byronosaurus to be the sister group of a polytomy consisting of the two Saurornithoides species from Asia and Troodon formosus of North America.[12] Sinornithoides was the sister group to this clade, with the unnamed Khamaryn Us troodontid being the sister group to all others.[15]

- Norell and others studied the evolutionary relationships between troodontids and other coelurosaurs. They found troodontids to be the sister group of a clade containing the oviraptorosaurs and therizinosaurs. Within Troodontidae they obtained similar results to their 2000 study, although this time they excluded the unnamed Khamaryn Us trodontid.[15]

- Makovicky and Gerald Grellet-Tinner noted commonalities between the type of egg microstructure seen in troodontid eggs and those of modern neognathous birds. However, they also noted that these similarities may have evolved separately rather than being inherited from a shared common ancestor.[5]

- Kevin Padian, Ji Qiang and Ji Shuan published a review of known feathered dinosaurs and their implications for the origin of flight.[16] The authors observed that many aspects of the distribution of feather homologues in the dinosaur family tree met the expectations of earlier phylogenetic hypotheses,[17] yet feathers were notably absent among troodontids despite the family's derived position within the coelurosaur family tree.[18]

- Xu Xing and others performed a cladistic analysis of the Dromaeosauridae.[19] They found the Troodontidae to be to sister taxon of the Dromaeosauridae.[19]

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Sinovenator changii.[3] They performed a cladistic analysis of the troodontidae based on the same character matrix as Norell and others used back in 2001. Xu and the others recovered the same relationships among troodontids as the other researchers with the exception of Sinovenator's presence at the base of the tree. Since it was extremely primitive for a troodontid Sinovenator may offer insights into the family's relationships with other theropod groups.[20]

- Xu and Norell described the new genus and species Mei long.[21]

- Xu and Wang described the new genus and species Sinusonasus magnodens.[22]

- Ji and others described the new genus and species Jinfengopteryx elegans.[23]

- Averianov and Sues described the new genus and species Urbacodon itemirensis.[24]

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Anchiornis huxleyi.[25]

- Norell and others described the new genus Zanabazar.[26]

2010s

- Senter and others described the new genus and species Geminiraptor suarezarum.[27]

- Lü Junchang and others described the new genus and species Xixiasaurus henanensis.[28]

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Linhevenator tani.[29]

- Zanno and others described the new genus and species Talos sampsoni.[30]

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Philovenator curriei.[31]

- Tsuihiji and others described the new genus and species Gobivenator mongoliensis.[32]

- Evans and others described the new genus and species Albertavenator curriei.

- Pei and others described the new genus and species Almas ukhaa.

- Shen and others described the new genus and species Daliansaurus liaoningensis.

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Jianianhualong tengi.

- van der Reest and Currie described the new genus and species Latenivenatrix mcmasterae.

- Shen and others described the new genus and species Liaoningvenator curriei.

- Troodon has a massive reassignment. The reassignment stated that Stenonychosaurus and the newly created genus Latenivenatrix are valid and not part of T.formosus. This limits Troodon to one species, with a range that is restricted to the Judith river formation. However David J. Varricchio disagreed with the reassessment [33]

- Hartman and others described the new genus and species Hesperornithoides miessleri.[34]

2020

- Remains of a Troodon species from the Prince Creek Formation were reported, but were not given an official name or formally described.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Horner (2001); "History of Dinosaur Collecting in Montana", page 44.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Introduction", page 184.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Table 9.1: Troodontidae", page 185.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Paleobiology", page 194.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Paleobiology", page 195.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Table 9.1: Troodontidae", page 186.

- ↑ Cope (1877).

- ↑ Nopcsa (1901).

- ↑ Kessler, Grigorescu, and Csiki (2005).

- ↑ Sternberg (1945).

- ↑ Holtz (2011); "Winter Appendix 2010".

- 1 2 3 Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", page 193.

- 1 2 3 Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Biogeography", page 194.

- ↑ Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Definition and Diagnosis", page 184.

- 1 2 Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", pages 193–194.

- ↑ Padian, Ji, and Ji (2001); "Abstract," page 117.

- ↑ Padian, Ji, and Ji (2001); "Conclusions," pages 131–132.

- ↑ Padian, Ji, and Ji (2001); "Conclusions," page 132.

- 1 2 Norell and Makovicky (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", page 207.

- ↑ Makovicky and Norell (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", page 194.

- ↑ Xu and Norell (2004); "Abstract," page 838.

- ↑ Xu and Wang (2004); "Abstract," page 22.

- ↑ Ji et al. (2005); "Abstract," page 197.

- ↑ Averianov and Sues (2007); "Abstract," page 87.

- ↑ Xu et al. (2009); "Abstract," page 430.

- ↑ Norell et al. (2009); "Abstract," page 63.

- ↑ Senter et al. (2010); "Abstract," page 1.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2010); "Abstract," page 381.

- ↑ Xu et al. (2011); "Abstract," page 1.

- ↑ Zanno et al. (2011); "Abstract," page 1.

- ↑ Xu et al. (2012); "Abstract," page 140.

- ↑ Tsuihiji et al. (2014); "Abstract," page 131.

- ↑ Varricchio, David J.; Kundrát, Martin; Hogan, Jason (2018). "An Intermediate Incubation Period and Primitive Brooding in a Theropod Dinosaur". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 12454. Bibcode:2018NatSR...812454V. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30085-6. PMC 6102251. PMID 30127534.

- ↑ Hartman, Scott; Mortimer, Mickey; Wahl, William R.; Lomax, Dean R.; Lippincott, Jessica; Lovelace, David M. (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

References

- Averianov, A.O.; Sues, H.-D. (2007). "A new troodontid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Cenomanian of Uzbekistan, with a review of troodontid records from the territories of the former Soviet Union". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[87:ANTDTF]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 9743271.

- Cope, Edward Drinker (1877). "Report on the geology of the region of the Judith River, Montana, and on vertebrate fossils obtained on or near the Missouri River". Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey. 3 (3): 565–597.

- Horner, John R. (2001). Dinosaurs Under the Big Sky. Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87842-445-8.

- Holtz, Thomas R. (2011). "Winter 2010 Appendix" (PDF). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.

- Ji, Q.; Ji, S.; Lu, J.; You, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. (2005). "First avialan bird from China (Jinfengopteryx elegans gen. et sp. nov.)". Geological Bulletin of China. 24 (3): 197–205.

- Junchang Lü; Li Xu; Yongqing Liu; Xingliao Zhang; Songhai Jia & Qiang Ji (2010). "A new troodontid (Theropoda: Troodontidae) from the Late Cretaceous of central China, and the radiation of Asian troodontids" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 55 (3): 381–388. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0047.

- Kessler, E.; Grigorescu, D.; Csiki, Z. (2005). "Elopteryx revisited – a new bird-like specimen from the Maastrichtian of the Hateg Basin". Acta Palaeontologica Romaniae. 5: 249–258.

- Mackovicky, Peter J.; Norell, Mark A. (2004). "Troodontidae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 184–195. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Nopcsa (1901). "Synopsis un Abstammung der Dinosaurier". Földtani Közlöny. Budapest. 31: 247–288.

- Norell, M.A. & Makovicky, P.J. (2004). "Dromaeosauridae". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 196–210. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Norell, M.A.; Makovicky, P.J.; Bever, G.S.; Balanoff, A.M.; Clark, J.M.; Barsbold, R.; Rowe, T. (2009). "A Review of the Mongolian Cretaceous Dinosaur Saurornithoides (Troodontidae: Theropoda)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3654): 63. doi:10.1206/648.1. hdl:2246/5973.

- Padian, K.; Ji, Qiang; Ji, Shu-An (2001). "Feathered dinosaurs and origin of flight". In Tanke, D. H.; Carpenter, K. (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Life of the Past. Indiana University Press. pp. 117–135.

- Phil Senter; James I. Kirkland; John Bird; Jeff A. Bartlett (2010). "A New Troodontid Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e14329. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514329S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014329. PMC 3002269. PMID 21179513.

- Sternberg, C.M. (1945). "Pachycephalosauridae proposed for domeheaded dinosaurs, Stegoceras lambei n. sp., described". Journal of Paleontology. 19: 534–538.

- Tsuihiji, T.; Barsbold, R.; Watabe, M.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Chinzorig, T.; Fujiyama, Y.; Suzuki, S. (2014). "An exquisitely preserved troodontid theropod with new information on the palatal structure from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". Naturwissenschaften. 101 (2): 131–142. Bibcode:2014NW....101..131T. doi:10.1007/s00114-014-1143-9. PMID 24441791. S2CID 13920021.

- Xing Xu & Mark A. Norell (2004). "A new troodontid dinosaur from China with avian-like sleeping posture" (PDF). Nature. 431 (7010): 838–841. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..838X. doi:10.1038/nature02898. PMID 15483610. S2CID 4362745.

- Xu, X.; Wang, X.-L. (2004). "A New Troodontid (Theropoda: Troodontidae) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Western Liaoning, China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 78 (1): 22–26. Bibcode:2004AcGlS..78...22X. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2004.tb00671.x. S2CID 129952609.

- Xu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Norell, M.; Sullivan, C.; Hone, D.; Erickson, G.; Wang, X.; Han, F. & Guo, Y. (2009). "A new feathered maniraptoran dinosaur fossil that fills a morphological gap in avian origin". Chinese Science Bulletin. 54 (3): 430–435. Bibcode:2009SciBu..54..430X. doi:10.1007/s11434-009-0009-6.

- Xing Xu; Qingwei Tan; Corwin Sullivan; Fenglu Han; Dong Xiao (2011). "A Short-Armed Troodontid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia and Its Implications for Troodontid Evolution". PLOS ONE. 6 (9): e22916. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622916X. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022916. PMC 3168428. PMID 21915256.

- Lindsay E. Zanno, David J. Varricchio, Patrick M. O'Connor, Alan L. Titus and Michael J. Knell (2011). "A new troodontid theropod, Talos sampsoni gen. et sp. nov., from the Upper Cretaceous Western Interior Basin of North America". PLOS ONE. 6 (9): e24487. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624487Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024487. PMC 3176273. PMID 21949721.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Xu Xing, Zhao Ji, Corwin Sullivan, Tan Qing-Wei, Martin Sander and Ma Qing-Yu (2012). "The taxonomy of the troodontid IVPP V 10597 reconsidered" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 50 (2): 140–150.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

Media related to Troodontidae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Troodontidae at Wikimedia Commons