| Zapsalis Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tooth of cf. Zapsalis from the Milk River Formation, with close up of denticles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Clade: | †Eudromaeosauria |

| Subfamily: | †Dromaeosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Zapsalis Cope, 1876 |

| Type species | |

| †Zapsalis abradens Cope, 1876 | |

Zapsalis is a genus of dromaeosaurine theropod dinosaurs. It is a tooth taxon, often considered dubious because of the fragmentary nature of the fossils, which include teeth but no other remains.

Etymology

The generic name is derived from Greek za~, "thorough", and psalis, "pair of scissors". The specific name means "abrading" in Latin.

History and classification

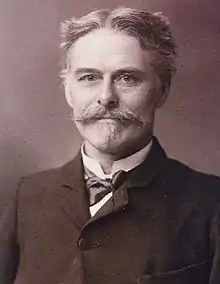

Fossils of Zapsalis were first described by American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in 1876 but as species of the large carnivorous theropod Laelaps (now Dryptosaurus).[1] Cope erected 2 species, Laelaps explanatus and L. laevifrons, the former based on a collection of 27 teeth and the latter based on a single tooth.[2][1] It wasn't until later in 1876 that Cope made the genus Zapsalis, with Z. abradens as the type, based on a second premaxillary tooth.[3] All of the fossils were collected from the Campanian age strata of the Judith River Formation in Montana, USA.[3][4][2] Cope named Zapsalis during the Bone Wars, his competition with Yale paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, to collect and describe as many fossil taxa as possible.[5]

After the Bone Wars, the type fossils of Zapsalis and the Laelaps species were sold to the American Museum of Natural History in New York.[2] In the wake of the Bone Wars, the complicated errors in dinosaur taxonomy were left to other paleontologists, with the Laelaps species being moved to other theropod dinosaurs like Deinodon,[6][7] Aublysodon,[8] and Dromaeosaurus.[9][10] Z. abradens was moved to Dromaeosaurus[9] and synonymized with the other Dromaeosaur Paronychodon.[11] It wasn't until 2002 that Julia Sankey e.a. concluded the teeth represented a separate "?Dromaeosaurus Morphotype A".[12] In 2013 Derek Larson and Philip Currie recognised Zapsalis as a valid taxon from the Judith River and Dinosaur Park Formation. The teeth are typified by a combination of rounded denticles, straight rear edge and vertical grooves. Similar teeth from the older Milk River Formation were referred to a cf. Zapsalis.[13] In 2019, Currie and Evans announced that the Zapsalis teeth from the Dinosaur Park Formation represented the second premaxillary tooth of Saurornitholestes langstoni, in a paper describing a complete skull of that species.[4] The authors kept the species distinct because the type species' holotype is likely indeterminate on a species level.[14]

As for Laelaps explanatus and L. laevifrons, they were never synonymized with Zapsalis but have been synonymized with Saurornitholestes langstoni and in turn, Zapsalis, as well.[2][4]

Description

The type tooth of Z. abradens is flat lingually, with no mesial serrations and 3 distal serrations per millimeter and is 12 mm in total length. There are three lingual ridges and four labial ones.[3][2] Currie & Evans, 2019 diagnosed Zapsalis from Saurornitholestes by noting the type of the former is lacking mesial serrations and being concave apicodistally, and therefore "recommended that the two genera be kept separate."[4] The second premaxillary teeth of Zapsalis and other dromaeosaurids may have been structurally specialized for preening feathers, as seen in some Oviraptorosaurs as well.[4]

Paleoenvironment

All 4 named species are known from the Judith River Formation, the site of expeditions first by Edward Drinker Cope's crews during the early stages of the Bone Wars, including the discoveries of many taxa that he named, though all are now seen as dubious. These include fossils of large, carnivorous tyrannosaurid theropods like Aublysodon and Deinodon. As for the herbivorous Ornithischians, like the beaked hadrosaurids Trachodon and Cionodon were named. The most common fossils are those of the horned Ceratopsians like Monoclonius, Ceratops, and Pteropelyx. Lastly, the armored ankylosaur Palaeoscincus is known from scattered teeth.[15]

See also

References

- 1 2 Cope, E. D. (1876). Descriptions of some vertebrate remains from the Fort Union beds of Montana. Proceedings of the Academy of natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 248-261.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Dromaeosaurs". www.theropoddatabase.com. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- 1 2 3 Cope, E. D. (1876). On some extinct reptiles and Batrachia from the Judith River and Fox Hills beds of Montana. Proceedings of the Academy of natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 340-359.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Currie, Philip J.; Evans, David C. (2019). "Cranial Anatomy of New Specimens of Saurornitholestes langstoni (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from the Dinosaur Park Formation (Campanian) of Alberta". The Anatomical Record. 303 (4): 691–715. doi:10.1002/ar.24241. PMID 31497925. S2CID 202002676.

- ↑ Brinkman, P. D. (2010). The second Jurassic dinosaur rush. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Osborn, H. F., & Lambe, L. M. (1902). On Vertebrata of the Mid-Cretaceous of the North West Territory (Vol. 3). Government Printing Bureau.

- ↑ Lambe, L. M. (1902). New genera and species from the Belly River series (Mid-Cretaceous). Contributions to Canadian Paleontology, Geological Survey of Canada 3: 25-81. 1918. The Cretaceous genus Stegoceras typifying a new family referred provisionally to the Stegosauria. Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, 12, 23-36.

- ↑ Hatcher, J. B. (1903). Osteology of Haplocanthosaurus, with description of a new species and remarks on the probable habits of the Sauropoda and the age and origin of the Atlantosaurus beds: additional remarks on Diplodocus (Vol. 2, No. 1). Carnegie Museum.

- 1 2 Matthew, W. D., & Brown, B. (1922). The family Deinodontidae, with notice of a new genus from the Cretaceous of Alberta. Bulletin of the AMNH; v. 46, article 6.

- ↑ Kuhn, O. (1939). Saurischia, Fossilium Catalogus I: Animalia, Pars 87. W. Quenstedt, Munich.

- ↑ Hotton III, N. (1965). Fossil Vertebrates from the Late Cretaceous Lance Formation, Eastern Wyoming.

- ↑ Sankey, J.T.; Brinkman, D.B.; Guenther, M.; Currie, P.J. (2002). "Small theropod and bird teeth from the Late Cretaceous (Upper Campanian) Judith River Group, Alberta" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 76: 751–763. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2002)076<0751:stabtf>2.0.co;2. S2CID 85973327.

- ↑ Larson, D. W.; Currie, P. J. (2013). Evans, Alistair Robert (ed.). "Multivariate Analyses of Small Theropod Dinosaur Teeth and Implications for Paleoecological Turnover through Time". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e54329. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...854329L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054329. PMC 3553132. PMID 23372708.

- ↑ Baszio, S. (1997). Systematic palaeontology of isolated dinosaur teeth from the latest Cretaceous of south Alberta, Canada. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, 196, 33-77.

- ↑ Cope, E.D. (1879). Hayden, F.V. (ed.). "The Relations of the Horizons of Extinct Vertebrata". United States Geological and Geographical Survey. 5 (1): 37–38.

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)