| Part of a series on |

| Paleontology |

|---|

|

|

Paleontology Portal Category |

The history of paleontology traces the history of the effort to understand the history of life on Earth by studying the fossil record left behind by living organisms. Since it is concerned with understanding living organisms of the past, paleontology can be considered to be a field of biology, but its historical development has been closely tied to geology and the effort to understand the history of Earth itself.

In ancient times, Xenophanes (570–480 BC), Herodotus (484–425 BC), Eratosthenes (276–194 BC), and Strabo (64 BC–24 AD) wrote about fossils of marine organisms, indicating that land was once under water. The ancient Chinese considered them to be dragon bones and documented them as such.[1] During the Middle Ages, fossils were discussed by Persian naturalist Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Europe) in The Book of Healing (1027), which proposed a theory of petrifying fluids that Albert of Saxony would elaborate on in the 14th century. The Chinese naturalist Shen Kuo (1031–1095) would propose a theory of climate change based on evidence from petrified bamboo.

In early modern Europe, the systematic study of fossils emerged as an integral part of the changes in natural philosophy that occurred during the Age of Reason.[2] The nature of fossils and their relationship to life in the past became better understood during the 17th and 18th centuries, and at the end of the 18th century, the work of Georges Cuvier had ended a long running debate about the reality of extinction, leading to the emergence of paleontology – in association with comparative anatomy – as a scientific discipline. The expanding knowledge of the fossil record also played an increasing role in the development of geology, and stratigraphy in particular.

In 1822, the word "paleontology" was used by the editor of a French scientific journal to refer to the study of ancient living organisms through fossils, and the first half of the 19th century saw geological and paleontological activity become increasingly well organized with the growth of geologic societies and museums and an increasing number of professional geologists and fossil specialists. This contributed to a rapid increase in knowledge about the history of life on Earth, and progress towards definition of the geologic time scale largely based on fossil evidence. As knowledge of life's history continued to improve, it became increasingly obvious that there had been some kind of successive order to the development of life. This would encourage early evolutionary theories on the transmutation of species.[3] After Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, much of the focus of paleontology shifted to understanding evolutionary paths, including human evolution, and evolutionary theory.[3]

The last half of the 19th century saw a tremendous expansion in paleontological activity, especially in North America.[2] The trend continued in the 20th century with additional regions of the Earth being opened to systematic fossil collection, as demonstrated by a series of important discoveries in China near the end of the 20th century. Many transitional fossils have been discovered, and there is now considered to be abundant evidence of how all classes of vertebrates are related, much of it in the form of transitional fossils.[4] The last few decades of the 20th century saw a renewed interest in mass extinctions and their role in the evolution of life on Earth.[5] There was also a renewed interest in the Cambrian explosion that saw the development of the body plans of most animal phyla. The discovery of fossils of the Ediacaran biota and developments in paleobiology extended knowledge about the history of life back far before the Cambrian.

Prior to the 17th century

As early as the 6th century BC, the Greek philosopher Xenophanes of Colophon (570–480 BC) recognized that some fossil shells were remains of shellfish, which he used to argue that what was at the time dry land was once under the sea.[6] Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), in an unpublished notebook, also concluded that some fossil sea shells were the remains of shellfish. However, in both cases, the fossils were complete remains of shellfish species that closely resembled living species, and were therefore easy to classify.[7]

In 1027, the Persian naturalist, Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Europe), proposed an explanation of how the stoniness of fossils was caused in The Book of Healing.[2] He modified an idea of Aristotle's, which explained it in terms of vaporous exhalations. Ibn Sina modified this into the theory of petrifying fluids (succus lapidificatus), which was elaborated on by Albert of Saxony in the 14th century and was accepted in some form by most naturalists by the 16th century.[8]

Shen Kuo (Chinese: 沈括) (1031–1095) of the Song Dynasty used marine fossils found in the Taihang Mountains to infer the existence of geological processes such as geomorphology and the shifting of seashores over time.[9] In 1088 AD, he discovered preserved petrified bamboos found underground in Yan'an, Shanbei region, Shaanxi province. Using his observation, he argued for a theory of gradual climate change, since Shaanxi was part of a dry climate zone that did not support a habitat for the growth of bamboos.[10]

As a result of a new emphasis on observing, classifying, and cataloging nature, 16th-century natural philosophers in Europe began to establish extensive collections of fossil objects (as well as collections of plant and animal specimens), which were often stored in specially built cabinets to help organize them. Conrad Gesner published a 1565 work on fossils that contained one of the first detailed descriptions of such a cabinet and collection. The collection belonged to a member of the extensive network of correspondents that Gesner drew on for his works. Such informal correspondence networks among natural philosophers and collectors became increasingly important during the course of the 16th century and were direct forerunners of the scientific societies that would begin to form in the 17th century. These cabinet collections and correspondence networks played an important role in the development of natural philosophy.[11]

However, most 16th-century Europeans did not recognize that fossils were the remains of living organisms. The etymology of the word fossil comes from the Latin for things having been dug up. As this indicates, the term was applied to a wide variety of stone and stone-like objects without regard to whether they might have an organic origin. 16th-century writers such as Gesner and Georg Agricola were more interested in classifying such objects by their physical and mystical properties than they were in determining the objects' origins.[12] In addition, the natural philosophy of the period encouraged alternative explanations for the origin of fossils. Both the Aristotelian and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy provided support for the idea that stony objects might grow within the earth to resemble living things. Neoplatonic philosophy maintained that there could be affinities between living and non-living objects that could cause one to resemble the other. The Aristotelian school maintained that the seeds of living organisms could enter the ground and generate objects resembling those organisms.[13]

Leonardo da Vinci and the development of paleontology

Leonardo da Vinci established a line of continuity between the two main branches of paleontology: body fossil palaeontology and ichnology.[14] In fact, Leonardo dealt with both major classes of fossils: (1) body fossils, e.g. fossilized shells; (2) ichnofossils (also known as trace fossils), i.e. the fossilized products of life-substrate interactions (e.g. burrows and borings). In folios 8 to 10 of the Leicester code, Leonardo examined the subject of body fossils, tackling one of the vexing issues of his contemporaries: why do we find petrified seashells on mountains?[14] Leonardo answered this question by correctly interpreting the biogenic nature of fossil mollusks and their sedimentary matrix.[15] The interpretation of Leonardo da Vinci appears extraordinarily innovative as he surpassed three centuries of scientific debate on the nature of body fossils.[16][17][18] Da Vinci took into consideration invertebrate ichnofossils to prove his ideas on the nature of fossil objects. To da Vinci, ichnofossils played a central role in demonstrating: (1) the organic nature of petrified shells and (2) the sedimentary origin of the rock layers bearing fossil objects. Da Vinci described what are bioerosion ichnofossils:[19]

The hills around Parma and Piacenza show abundant mollusks and bored corals still attached to the rocks. When I was working on the great horse in Milan, certain peasants brought me a huge bagful of them

— Leicester Code, folio 9r

Such fossil borings allowed Leonardo to confute the Inorganic theory, i.e. the idea that so-called petrified shells (mollusk body fossils) are inorganic curiosities. With the words of Leonardo da Vinci:[20][14]

[the Inorganic theory is not true] because there remains the trace of the [animal's] movements on the shell which [it] consumed in the same manner of a woodworm in wood ...

— Leicester Code, folio 9v

Da Vinci discussed not only fossil borings, but also burrows. Leonardo used fossil burrows as paleoenvironmental tools to demonstrate the marine nature of sedimentary strata:[19]

Between one layer and the other there remain traces of the worms that crept between them when they had not yet dried. All the sea mud still contains shells, and the shells are petrified together with the mud

— Leicester Code, folio 10v

Other Renaissance naturalists studied invertebrate ichnofossils during the Renaissance, but none of them reached such accurate conclusions.[21] Leonardo's considerations of invertebrate ichnofossils are extraordinarily modern not only when compared to those of his contemporaries, but also to interpretations in later times. In fact, during the 1800s invertebrate ichnofossils were explained as fucoids, or seaweed, and their true nature was widely understood only by the early 1900s.[22][23][24] For these reasons, Leonardo da Vinci is deservedly considered the founding father of both the major branches of palaeontology, i.e. the study of body fossils and ichnology.[14]

17th century

During the Age of Reason, fundamental changes in natural philosophy were reflected in the analysis of fossils. In 1665 Athanasius Kircher attributed giant bones to extinct races of giant humans in his Mundus subterraneus. In the same year Robert Hooke published Micrographia, an illustrated collection of his observations with a microscope. One of these observations was entitled "Of Petrify'd wood, and other Petrify'd bodies", which included a comparison between petrified and ordinary wood. He concluded that petrified wood was ordinary wood that had been soaked with "water impregnated with stony and earthy particles". He then suggested that several kinds of fossil sea shells were formed from ordinary shells by a similar process. He argued against the prevalent view that such objects were "Stones form'd by some extraordinary Plastick virtue latent in the Earth itself".[25] Hooke believed that fossils provided evidence about the history of life on Earth writing in 1668:

...if the finding of Coines, Medals, Urnes, and other Monuments of famous persons, or Towns, or Utensils, be admitted for unquestionable Proofs, that such Persons or things have, in former times had a being, certainly those Petrifactions may be allowed to be of equal Validity and Evidence, that there have formerly been such Vegetables or Animals... and are true universal Characters legible to all rational Men.[26]

Hooke was prepared to accept the possibility that some such fossils represented species that had become extinct, possibly in past geological catastrophes.[26]

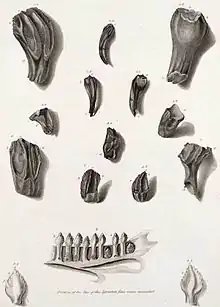

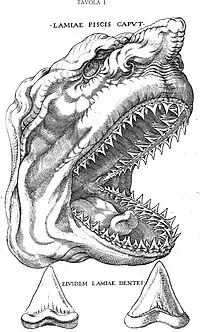

In 1667 Nicholas Steno wrote a paper about a shark head he had dissected. He compared the teeth of the shark with the common fossil objects known as "tongue stones" or glossopetrae. He concluded that the fossils must have been shark teeth. Steno then took an interest in the question of fossils, and to address some of the objections to their organic origin he began studying rock strata. The result of this work was published in 1669 as Forerunner to a Dissertation on a solid naturally enclosed in a solid. In this book, Steno drew a clear distinction between objects such as rock crystals that really were formed within rocks and those such as fossil shells and shark teeth that were formed outside of those rocks. Steno realized that certain kinds of rock had been formed by the successive deposition of horizontal layers of sediment and that fossils were the remains of living organisms that had become buried in that sediment. Steno who, like almost all 17th-century natural philosophers, believed that the earth was only a few thousand years old, resorted to the Biblical flood as a possible explanation for fossils of marine organisms that were far from the sea.[27]

Despite the considerable influence of Forerunner, naturalists such as Martin Lister (1638–1712) and John Ray (1627–1705) continued to question the organic origin of some fossils. They were particularly concerned about objects such as fossil Ammonites, which Hooke claimed were organic in origin, that did not resemble any known living species. This raised the possibility of extinction, which they found difficult to accept for philosophical and theological reasons.[28] In 1695 Ray wrote to the Welsh naturalist Edward Lluyd complaining of such views: "... there follows such a train of consequences, as seem to shock the Scripture-History of the novity of the World; at least they overthrow the opinion received, & not without good reason, among Divines and Philosophers, that since the first Creation there have been no species of Animals or Vegetables lost, no new ones produced."[29]

18th century

In his 1778 work Epochs of Nature Georges Buffon referred to fossils, in particular the discovery of fossils of tropical species such as elephants and rhinoceros in northern Europe, as evidence for the theory that the earth had started out much warmer than it currently was and had been gradually cooling.

In 1796 Georges Cuvier presented a paper on living and fossil elephants comparing skeletal remains of Indian and African elephants to fossils of mammoths and of an animal he would later name mastodon utilizing comparative anatomy. He established for the first time that Indian and African elephants were different species, and that mammoths differed from both and must be extinct. He further concluded that the mastodon was another extinct species that also differed from Indian or African elephants, more so than mammoths. Cuvier made another powerful demonstration of the power of comparative anatomy in paleontology when he presented a second paper in 1796 on a large fossil skeleton from Paraguay, which he named Megatherium and identified as a giant sloth by comparing its skull to those of two living species of tree sloth. Cuvier's ground-breaking work in paleontology and comparative anatomy led to the widespread acceptance of extinction.[30] It also led Cuvier to advocate the geological theory of catastrophism to explain the succession of organisms revealed by the fossil record. He also pointed out that since mammoths and woolly rhinoceros were not the same species as the elephants and rhinoceros currently living in the tropics, their fossils could not be used as evidence for a cooling earth.

In a pioneering application of stratigraphy, William Smith, a surveyor and mining engineer, made extensive use of fossils to help correlate rock strata in different locations. He created the first geological map of England during the late 1790s and early 19th century. He established the principle of faunal succession, the idea that each strata of sedimentary rock would contain particular types of fossils, and that these would succeed one another in a predictable way even in widely separated geologic formations. At the same time, Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart, an instructor at the Paris school of mine engineering, used similar methods in an influential study of the geology of the region around Paris.

Early to mid-19th century

The study of fossils and the origin of the word paleontology

The Smithsonian Libraries consider that the first edition of a work which laid the foundation to vertebrate paleontology was Georges Cuvier's Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes (Researches on quadruped fossil bones), published in France in 1812.[31] Referring to the second edition of this work (1821), Cuvier's disciple and editor of the scientific publication Journal de physique Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville published in January 1822, in the Journal de physique, an article titled "Analyse des principaux travaux dans les sciences physiques, publiés dans l'année 1821" ("Analysis of the main works in the physical sciences, published in the year 1821"). In this article Blainville unveiled for the first time the printed word palæontologie[32] which later gave the English word "paleontology". Blainville had already coined the term paléozoologie in 1817 to refer to the work Cuvier and others were doing to reconstruct extinct animals from fossil bones. However, Blainville began looking for a term that could refer to the study of both fossil animal and plant remains. After trying some unsuccessful alternatives, he hit on "palaeontologie" in 1822. Blainville's term for the study of the fossilized organisms quickly became popular and was anglicized into "paleontology".[33]

In 1828 Alexandre Brongniart's son, the botanist Adolphe Brongniart, published the introduction to a longer work on the history of fossil plants. Adolphe Brongniart concluded that the history of plants could roughly be divided into four parts. The first period was characterized by cryptogams. The second period was characterized by the appearance of the conifers. The third period brought emergence of the cycads, and the fourth by the development of the flowering plants (such as the dicotyledons). The transitions between each of these periods was marked by sharp discontinuities in the fossil record, with more gradual changes within the periods. Brongniart's work is the foundation of paleobotany and reinforced the theory that life on earth had a long and complex history, and different groups of plants and animals made their appearances in successive order.[34] It also supported the idea that the Earth's climate had changed over time as Brongniart concluded that plant fossils showed that during the Carboniferous the climate of Northern Europe must have been tropical.[35] The term "paleobotany" was coined in 1884 and "palynology" in 1944.

The age of mammals

In 1804, Cuvier identified two fossil mammal genera from the gypsum quarries of the outskirts of Paris (known as the Paris Basin) in France (although the fossils were known by him as early as at least 1800). Unlike earlier-discovered fossil mammals like Megatherium and Mammut, the 1804-described fossil mammals were discovered from deeper deposits instead of surface deposits, indicating older ages (late Eocene epoch). He identified that the two genera were definitely mammals based on dental and postcranial evidence and were similar to extant mammals such as tapirs, camels, and pigs. However, he also identified that they differed from each other and extant mammals based on dental evidence. He named the two genera Palaeotherium and Anoplotherium.[39][40][41] Later in 1807, he wrote about two incomplete skeletons of A. commune that were just recently uncovered from the communes of Pantin and Antony, respectively. Despite the skeletons being incomplete and the first being partially damaged from not being carefully collected by workers, he was able to determine based on postcranial evidence that A. commune was similar to animals that would eventually be classified in the order Artiodactyla after his lifetime. However, Cuvier expressed his surprise at how A. commune sported highly unusual traits of which there are no modern analogues in its extant relatives, such as a long and robust tail of 22 caudal vertebrae and third small fingers in its feet in addition to two long ones.[42][43]

In 1812, Cuvier followed up with published drawn reconstructions on known remains of "Palaeotherium" minor (= Plagiolophus minor), "Anoplotherium medium" (= Xiphodon gracilis), and, most famously, Anoplotherium commune. In A. commune, he was able to predict accurately that A. commune had robust muscles in its entire body to support its short limbs and long tail. He also described hypothesized paleobiologies of the different species assigned to Anoplotherium (some of which would eventually be assigned to different Paleogene artiodactyls such as Xiphodon and Dichobune). His skeletal reconstructions of fossil mammal genera and hypothesis of paleoecological behaviors are considered amongst the earliest instances within paleontology.[36][44] He also drew muscle reconstructions of A. commune based on known skeletal remains of the species, which were reprinted but never published to the public out of his concern that they were too speculative. Today, however, his muscle reconstructions of A. commune are seen as accurate and having paved the way for paleoart and biomechanics.[45]

The age of reptiles

In 1808, Cuvier identified a fossil found in Maastricht as a giant marine reptile that would later be named Mosasaurus. He also identified, from a drawing, another fossil found in Bavaria as a flying reptile and named it Pterodactylus. He speculated, based on the strata in which these fossils were found, that large reptiles had lived prior to what he was calling "the age of mammals".[46] Cuvier's speculation would be supported by a series of finds that would be made in Great Britain over the course of the next two decades. Mary Anning, a professional fossil collector since age eleven, collected the fossils of a number of marine reptiles and prehistoric fish from the Jurassic marine strata at Lyme Regis. These included the first ichthyosaur skeleton to be recognized as such, which was collected in 1811, and the first two plesiosaur skeletons ever found in 1821 and 1823. Mary Anning was only 12 when she and her brother discovered the Ichthyosaurus skeleton. Many of her discoveries would be described scientifically by the geologists William Conybeare, Henry De la Beche, and William Buckland.[47] It was Anning who observed that stony objects known as "bezoar stones" were often found in the abdominal region of ichthyosaur skeletons, and she noted that if such stones were broken open they often contained fossilized fish bones and scales as well as sometimes bones from small ichthyosaurs. This led her to suggest to Buckland that they were fossilized feces, which he named coprolites, and which he used to better understand ancient food chains.[48] Mary Anning made many fossil discoveries that revolutionized science. However, despite her phenomenal scientific contributions, she was rarely recognized officially for her discoveries. Her discoveries were often credited to wealthy men who bought her fossils.[49]

In 1824, Buckland found and described a lower jaw from Jurassic deposits from Stonesfield. He determined that the bone belonged to a carnivorous land-dwelling reptile he called Megalosaurus. That same year Gideon Mantell realized that some large teeth he had found in 1822, in Cretaceous rocks from Tilgate, belonged to a giant herbivorous land-dwelling reptile. He called it Iguanodon, because the teeth resembled those of an iguana. All of this led Mantell to publish an influential paper in 1831 entitled "The Age of Reptiles" in which he summarized the evidence for there having been an extended time during which the earth had teemed with large reptiles, and he divided that era, based in what rock strata different types of reptiles first appeared, into three intervals that anticipated the modern periods of the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous.[50] In 1832 Mantell would find, in Tilgate, a partial skeleton of an armored reptile he would call Hylaeosaurus. In 1841 the English anatomist Richard Owen would create a new order of reptiles, which he called Dinosauria, for Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus.[51]

This evidence that giant reptiles had lived on Earth in the past caused great excitement in scientific circles,[52] and even among some segments of the general public.[53] Buckland did describe the jaw of a small primitive mammal, Phascolotherium, that was found in the same strata as Megalosaurus. This discovery, known as the Stonesfield mammal, was a much discussed anomaly. Cuvier at first thought it was a marsupial, but Buckland later realized it was a primitive placental mammal. Due to its small size and primitive nature, Buckland did not believe it invalidated the overall pattern of an age of reptiles, when the largest and most conspicuous animals had been reptiles rather than mammals.[54]

Catastrophism, uniformitarianism and the fossil record

In Cuvier's landmark 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he referred to a single catastrophe that destroyed life to be replaced by the current forms. As a result of his studies of extinct mammals, he realized that animals such as Palaeotherium and Anoplotherium had lived before the time of the mammoths, which led him to write in terms of multiple geological catastrophes that had wiped out a series of successive faunas.[55] By 1830, a scientific consensus had formed around his ideas as a result of paleobotany and the dinosaur and marine reptile discoveries in Britain.[56] In Great Britain, where natural theology was very influential in the early 19th century, a group of geologists that included Buckland, and Robert Jameson insisted on explicitly linking the most recent of Cuvier's catastrophes to the biblical flood. Catastrophism had a religious overtone in Britain that was absent elsewhere.[57]

Partly in response to what he saw as unsound and unscientific speculations by William Buckland and other practitioners of flood geology, Charles Lyell advocated the geological theory of uniformitarianism in his influential work Principles of Geology.[58] Lyell amassed evidence, both from his own field research and the work of others, that most geological features could be explained by the slow action of present-day forces, such as vulcanism, earthquakes, erosion, and sedimentation rather than past catastrophic events.[59] Lyell also claimed that the apparent evidence for catastrophic changes in the fossil record, and even the appearance of directional succession in the history of life, were illusions caused by imperfections in that record. For instance he argued that the absence of birds and mammals from the earliest fossil strata was merely an imperfection in the fossil record attributable to the fact that marine organisms were more easily fossilized.[59] Also Lyell pointed to the Stonesfield mammal as evidence that mammals had not necessarily been preceded by reptiles, and to the fact that certain Pleistocene strata showed a mixture of extinct and still surviving species, which he said showed that extinction occurred piecemeal rather than as a result of catastrophic events.[60] Lyell was successful in convincing geologists of the idea that the geological features of the earth were largely due to the action of the same geologic forces that could be observed in the present day, acting over an extended period of time. He was not successful in gaining support for his view of the fossil record, which he believed did not support a theory of directional succession.[61]

Transmutation of species and the fossil record

In the early 19th century Jean Baptiste Lamarck used fossils to argue for his theory of the transmutation of species.[62] Fossil finds, and the emerging evidence that life had changed over time, fueled speculation on this topic during the next few decades.[63] Robert Chambers used fossil evidence in his 1844 popular science book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, which advocated an evolutionary origin for the cosmos as well as for life on earth. Like Lamarck's theory it maintained that life had progressed from the simple to the complex.[64] These early evolutionary ideas were widely discussed in scientific circles but were not accepted into the scientific mainstream.[65] Many of the critics of transmutational ideas used fossil evidence in their arguments. In the same paper that coined the term dinosaur Richard Owen pointed out that dinosaurs were at least as sophisticated and complex as modern reptiles, which he claimed contradicted transmutational theories.[66] Hugh Miller would make a similar argument, pointing out that the fossil fish found in the Old Red Sandstone formation were fully as complex as any later fish, and not the primitive forms alleged by Vestiges.[67] While these early evolutionary theories failed to become accepted as mainstream science, the debates over them would help pave the way for the acceptance of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection a few years later.[68]

Geological time scale and the history of life

Geologists such as Adam Sedgwick, and Roderick Murchison continued, in the course of disputes such as the Great Devonian controversy, to make advances in stratigraphy. They described newly recognized geological periods, such as the Cambrian, the Silurian, the Devonian, and the Permian. Increasingly, such progress in stratigraphy depended on the opinions of experts with specialized knowledge of particular types of fossils such as William Lonsdale (fossil corals), and John Lindley (fossil plants) who both played a role in the Devonian controversy and its resolution.[69] By the early 1840s much of the geologic time scale had been developed. In 1841, John Phillips formally divided the geologic column into three major eras, the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic, based on sharp breaks in the fossil record.[70] He identified the three periods of the Mesozoic era and all the periods of the Paleozoic era except the Ordovician. His definition of the geological time scale is still used today.[71] It remained a relative time scale with no method of assigning any of the periods' absolute dates. It was understood that not only had there been an "age of reptiles" preceding the current "age of mammals", but there had been a time (during the Cambrian and the Silurian) when life had been restricted to the sea, and a time (prior to the Devonian) when invertebrates had been the largest and most complex forms of animal life.

Expansion and professionalization of geology and paleontology

This rapid progress in geology and paleontology during the 1830s and 1840s was aided by a growing international network of geologists and fossil specialists whose work was organized and reviewed by an increasing number of geological societies. Many of these geologists and paleontologists were now paid professionals working for universities, museums and government geological surveys. The relatively high level of public support for the earth sciences was due to their cultural impact, and their proven economic value in helping to exploit mineral resources such as coal.[72]

Another important factor was the development in the late 18th and early 19th centuries of museums with large natural history collections. These museums received specimens from collectors around the world and served as centers for the study of comparative anatomy and morphology. These disciplines played key roles in the development of a more technically sophisticated form of natural history. One of the first and most important examples was the Museum of Natural History in Paris, which was at the center of many of the developments in natural history during the first decades of the 19th century. It was founded in 1793 by an act of the French National Assembly, and was based on an extensive royal collection plus the private collections of aristocrats confiscated during the French Revolution, and expanded by material seized in French military conquests during the Napoleonic Wars. The Paris museum was the professional base for Cuvier, and his professional rival Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. The English anatomists Robert Grant and Richard Owen both spent time studying there. Owen would go on to become the leading British morphologist while working at the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons.[73][74]

Late 19th century

Evolution

Charles Darwin's publication of the On the Origin of Species in 1859 was a watershed event in all the life sciences, especially paleontology. Fossils had played a role in the development of Darwin's theory. In particular he had been impressed by fossils he had collected in South America during the voyage of the Beagle of giant armadillos, giant sloths, and what at the time he thought were giant llamas that seemed to be related to species still living on the continent in modern times.[75] The scientific debate that started immediately after the publication of Origin led to a concerted effort to look for transitional fossils and other evidence of evolution in the fossil record. There were two areas where early success attracted considerable public attention, the transition between reptiles and birds, and the evolution of the modern single-toed horse.[76] In 1861 the first specimen of Archaeopteryx, an animal with both teeth and feathers and a mix of other reptilian and avian features, was discovered in a limestone quarry in Bavaria and described by Richard Owen. Another would be found in the late 1870s and put on display at the Natural History Museum, Berlin in 1881. Other primitive toothed birds were found by Othniel Marsh in Kansas in 1872. Marsh also discovered fossils of several primitive horses in the Western United States that helped trace the evolution of the horse from the small 5-toed Hyracotherium of the Eocene to the much larger single-toed modern horses of the genus Equus. Thomas Huxley would make extensive use of both the horse and bird fossils in his advocacy of evolution. Acceptance of evolution occurred rapidly in scientific circles, but acceptance of Darwin's proposed mechanism of natural selection as the driving force behind it was much less universal. In particular some paleontologists such as Edward Drinker Cope and Henry Fairfield Osborn preferred alternatives such as neo-Lamarckism, the inheritance of characteristics acquired during life, and orthogenesis, an innate drive to change in a particular direction, to explain what they perceived as linear trends in evolution.[77]

There was also great interest in human evolution. Neanderthal fossils were discovered in 1856, but at the time it was not clear that they represented a different species from modern humans. Eugene Dubois created a sensation with his discovery of Java Man, the first fossil evidence of a species that seemed clearly intermediate between humans and apes, in 1891.[78]

Developments in North America

A major development in the second half of the 19th century was a rapid expansion of paleontology in North America. In 1858 Joseph Leidy described a Hadrosaurus skeleton, which was the first North American dinosaur to be described from good remains. However, it was the massive westward expansion of railroads, military bases, and settlements into Kansas and other parts of the Western United States following the American Civil War that really fueled the expansion of fossil collection.[79] The result was an increased understanding of the natural history of North America, including the discovery of the Western Interior Sea that had covered Kansas and much of the rest of the Midwestern United States during parts of the Cretaceous, the discovery of several important fossils of primitive birds and horses, and the discovery of a number of new dinosaur genera including Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Triceratops. Much of this activity was part of a fierce personal and professional rivalry between two men, Othniel Marsh, and Edward Cope, which has become known as the Bone Wars.[80]

Overview of developments in the 20th century

Developments in geology

Two 20th-century developments in geology had a big effect on paleontology. The first was the development of radiometric dating, which allowed absolute dates to be assigned to the geologic timescale. The second was the theory of plate tectonics, which helped make sense of the geographical distribution of ancient life.

Geographical expansion of paleontology

During the 20th century, paleontological exploration intensified everywhere and ceased to be a largely European and North American activity. In the 135 years between Buckland's first discovery and 1969 a total of 170 dinosaur genera were described. In the 25 years after 1969 that number increased to 315. Much of this increase was due to the examination of new rock exposures, particularly in previously little-explored areas in South America and Africa.[81] Near the end of the 20th century the opening of China to systematic exploration for fossils has yielded a wealth of material on dinosaurs and the origin of birds and mammals.[82] Also study of the Chengjiang fauna, a Cambrian fossil site in China, during the 1990s has provided important clues to the origin of vertebrates.[83]

Mass extinctions

The 20th century saw a major renewal of interest in mass extinction events and their effect on the course of the history of life. This was particularly true after 1980 when Luis and Walter Alvarez put forward the Alvarez hypothesis claiming that an impact event caused the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which killed off the non-avian dinosaurs along with many other living things.[84] Also in the early 1980s Jack Sepkoski and David M. Raup published papers with statistical analysis of the fossil record of marine invertebrates that revealed a pattern (possibly cyclical) of repeated mass extinctions with significant implications for the evolutionary history of life.

Evolutionary paths and theory

Throughout the 20th century new fossil finds continued to contribute to understanding the paths taken by evolution. Examples include major taxonomic transitions such as finds in Greenland, starting in the 1930s (with more major finds in the 1980s), of fossils illustrating the evolution of tetrapods from fish, and fossils in China during the 1990s that shed light on the dinosaur-bird relationship. Other events that have attracted considerable attention have included the discovery of a series of fossils in Pakistan that have shed light on whale evolution, and most famously of all a series of finds throughout the 20th century in Africa (starting with Taung child in 1924[85]) and elsewhere have helped illuminate the course of human evolution. Increasingly, at the end of the 20th century, the results of paleontology and molecular biology were being brought together to reveal detailed phylogenetic trees.

The results of paleontology have also contributed to the development of evolutionary theory. In 1944 George Gaylord Simpson published Tempo and Mode in Evolution, which used quantitative analysis to show that the fossil record was consistent with the branching, non-directional, patterns predicted by the advocates of evolution driven by natural selection and genetic drift rather than the linear trends predicted by earlier advocates of neo-Lamarckism and orthogenesis. This integrated paleontology into the modern evolutionary synthesis.[86] In 1972 Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould used fossil evidence to advocate the theory of punctuated equilibrium, which maintains that evolution is characterized by long periods of relative stasis and much shorter periods of relatively rapid change.[87]

Cambrian explosion

One area of paleontology that has seen a lot of activity during the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond is the study of the Cambrian explosion during which many of the various phyla of animals with their distinctive body plans first appear. The well-known Burgess Shale Cambrian fossil site was found in 1909 by Charles Doolittle Walcott, and another important site in Chengjiang China was found in 1912. However, new analysis in the 1980s by Harry B. Whittington, Derek Briggs, Simon Conway Morris and others sparked a renewed interest and a burst of activity including discovery of an important new fossil site, Sirius Passet, in Greenland, and the publication of a popular and controversial book, Wonderful Life by Stephen Jay Gould in 1989.[88]

Pre-Cambrian fossils

Prior to 1950 there was no widely accepted fossil evidence of life before the Cambrian period. When Charles Darwin wrote The Origin of Species he acknowledged that the lack of any fossil evidence of life prior to the relatively complex animals of the Cambrian was a potential argument against the theory of evolution, but expressed the hope that such fossils would be found in the future. In the 1860s there were claims of the discovery of pre-Cambrian fossils, but these would later be shown not to have an organic origin. In the late 19th century Charles Doolittle Walcott would discover stromatolites and other fossil evidence of pre-Cambrian life, but at the time the organic origin of those fossils was also disputed. This would start to change in the 1950s with the discovery of more stromatolites along with microfossils of the bacteria that built them, and the publication of a series of papers by the Soviet scientist Boris Vasil'evich Timofeev announcing the discovery of microscopic fossil spores in pre-Cambrian sediments. A key breakthrough would come when Martin Glaessner would show that fossils of soft bodied animals discovered by Reginald Sprigg during the late 1940s in the Ediacaran hills of Australia were in fact pre-Cambrian not early Cambrian as Sprigg had originally believed, making the Ediacaran biota the oldest animals known. By the end of the 20th century, paleobiology had established that the history of life extended back at least 3.5 billion years.[89]

See also

- History of biology

- History of evolutionary thought

- History of geology

- History of science

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of years in paleontology

- Taxonomy of commonly fossilised invertebrates

- Timeline of paleontology

- Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology

- History of paleontology in the United States

Notes

- ↑ Dong 1992

- 1 2 3 Garwood, Russell J. (2012). "Life as a palaeontologist: Palaeontology for dummies, Part 2". Palaeontology Online. 4 (2): 1–1o. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- 1 2 Buckland W, Gould SJ (1980). Geology and Mineralogy Considered With Reference to Natural Theology (History of Paleontology). Ayer Company Publishing. ISBN 978-0-405-12706-9.

- ↑ Prothero, D (2008-02-27). "Evolution: What missing link?". New Scientist. No. 2645. pp. 35–40.

- ↑ Bowler Evolution: The History of an Idea pp. 351–352

- ↑ Desmond pp. 692–697.

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils p. 39

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils p. 24

- ↑ Shen Kuo,Mengxi Bitan (梦溪笔谈; Dream Pool Essays) (1088)

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, p. 614.

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 9–17

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 23–33

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 33–36

- 1 2 3 4 Baucon, A. (2010). "Leonardo da Vinci, the founding father of ichnology". PALAIOS. 25 (6): 361–367. Bibcode:2010Palai..25..361B. doi:10.2110/palo.2009.p09-049r. S2CID 86011122.

- ↑ Baucon A., Bordy E., Brustur T., Buatois L., Cunningham T., De C., Duffin C., Felletti F., Gaillard C., Hu B., Hu L., Jensen S., Knaust D., Lockley M., Lowe P., Mayor A., Mayoral E., Mikulas R., Muttoni G., Neto de Carvalho C., Pemberton S., Pollard J., Rindsberg A., Santos A., Seike K., Song H., Turner S., Uchman A., Wang Y., Yi-ming G., Zhang L., Zhang W. (2012). "A history of ideas in ichnology". In Bromley, R.G.; Knaust, D. (eds.). Trace Fossils as Indicators of Sedimentary Environments. Developments in Sedimentology. Vol. 64. ISBN 9780444538147.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Rudwick, M.J.S., 1976, The Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in the History of Palaeontology: University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 308 p.

- ↑ VAI, G.B., 1995, Geological priorities in Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks and paintings, in Giglia, G., Maccagni, C., and Morello, N., eds., Rocks, Fossils and History: INHIGEO, Festina Lente, Firenze, pp. 13–26

- ↑ VAI, G.B., 2003, I viaggi di Leonardo lungo le valli romagnole: Riflessi di geologia nei quadri, disegni e codici, in Perdetti, C., ed., Leonardo, Macchiavelli, Cesare Borgia (1500–1503): Arte Storia e Scienza in Romagna: De Luca Editori d’Arte, Rome, pp. 37–48

- 1 2 Baucon, A. 2010. Da Vinci’s Paleodictyon: the fractal beauty of traces. Acta Geologica Polonica, 60(1). Available from the author's homepage

- ↑ Baucon, A. 2008. Italy, the Cradle of Ichnology: the legacy of Aldrovandi and Leonardo. In: Avanzini M., Petti F. Italian Ichnology, Studi Trent. Sci. Nat. Acta Geol., 83. Paper available from the author's homepage

- ↑ Baucon A. 2009. Ulisse Aldrovandi: the study of trace fossils during the Renaissance. Ichnos 16(4). Abstract available from the author's homepage

- ↑ Osgood, R.G., 1975, The history of invertebrate ichnology, in Frey, R.W., ed., The Study of Trace Fossils: Springer Verlag, New York, pp. 3–12.

- ↑ Osgood, R.G., 1970, Trace fossils of the Cincinnati area: Paleontographica Americana, v. 6, no. 41, pp. 281–444.

- ↑ Pemberton, S.G., MacEachern, J.A., and Gingras, M.K., 2007, The antecedents of invertebrate ichnology in North America: The Canadian and Cincinnati schools, in Miller, W., III, ed., Trace Fossils. Concepts, Problems, Prospects: Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 14–31.

- ↑ Hooke Micrographia observation XVII

- 1 2 Bowler The Earth Encompassed (1992) pp. 118–119

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 72–73

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 61–65

- ↑ Bowler The Earth Encompassed (1992) p. 117

- ↑ McGowan the dragon seekers pp. 3–4

- ↑ Georges Cuvier, [https://archive.org/details/recherchessurles21812cuvi Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes, 1812, Paris ("First edition of a work which laid the foundation to vertebrate paleontology")

- ↑ Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville, "Analyse des principaux travaux dans les sciences physiques, publiés dans l'année 1821", Journal de phyique, tome XCIV, p. 54

- ↑ Rudwick Worlds before Adam p. 48

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 145–147

- ↑ Bowler The Earth Encompassed (1992)

- 1 2 Cuvier, Geoges (1812). "Résumé général et rétablissement des Squelettes des diverses espèces". Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes: où l'on rétablit les caractères de plusieurs espèces d'animaux que les révolutions du globe paroissent avoir détruites (in French). Vol. 3. Chez Deterville.

- ↑ Dor, M. (1938). "Sur la biologie de l'Anoplotherium (L'Anoplotherium était-il aquatique?)". Mammalia. 2: 43–48.

- ↑ Hooker, Jerry J. (2007). "Bipedal browsing adaptations of the unusual Late Eocene–earliest Oligocene tylopod Anoplotherium (Artiodactyla, Mammalia)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 151 (3): 609–659. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00352.x.

- ↑ Cuvier, Georges (1804). "Suite des Recherches: Sur les espèces d'animaux dont proviennent les os fossiles répandus dans la pierre à plâtre des environs de Paris". Annales du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris (in French). 3: 364–387.

- ↑ Rudwick, Martin J. S. (2022). "Georges Cuvier's appeal for international collaboration, 1800". History of Geology. 46 (1): 117–125. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2022/022002. S2CID 246893918.

- ↑ Belhoste, Bruno (2017). "Chapter 10: From Quarry to Paper. Cuvier's Three Epistemological Cultures". In Chemla, Karine; Keller, Evelyn Fox (eds.). Cultures without Culturalism: The Making of Scientific Knowledge. Duke University Press. pp. 250–277.

- ↑ Cuvier, Georges (1807). "Suite des recherches sur les os fossiles des environs de Paris. Troisième mémoire, troisième section, les phalanges. Quatrième mémoire sur les os des extrémités, première section, les os longs des extrémités postérieures". Annales du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle. 9: 10–44.

- ↑ Cuvier, Georges (1807). "Suite des recherches sur les os fossiles des environs de Paris. Ve mémoire, IIe section, description de deux skelettes presque entiers d'Anoplotherium commune". Annales du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle (in French). 9: 272–282.

- ↑ Rudwick, Martin J. S. (1997). "Chapter 6: The Animals from the Gypsum Beds around Paris". Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes: New Translations and Interpretations of the Primary Texts. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Witton, Mark P.; Michel, Ellinor (2022). "Chapter 4: The sculptures: mammals". The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. The Crowood Press. pp. 68–91.

- ↑ Rudwick Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones and Geological Catastrophes p. 158

- ↑ McGowan pp. 11–27

- ↑ Rudwick, Martin Worlds Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform (2008) pp. 154–155.

- ↑ "Mary Anning: the unsung hero of fossil discovery". www.nhm.ac.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ↑ Cadbury, Deborah The Dinosaur Hunters (2000) pp. 171–175.

- ↑ McGowan p. 176

- ↑ McGowan pp. 70–87

- ↑ McGowan p. 109

- ↑ McGowan pp. 78–79

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 124–125

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 156–157

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 133–136

- ↑ McGowan pp. 93–95

- 1 2 McGowan pp. 100–103

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 178–184

- ↑ McGowan pp. 100

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils p. 119

- ↑ McGowan p. 8

- ↑ McGowan pp. 188–191

- ↑ Larson p. 73

- ↑ Larson p. 44

- ↑ Ruckwick The Meaning of fossils pp. 206–207

- ↑ Larson p. 51

- ↑ Rudwick The Great Devonian Controversy p. 94

- ↑ Larson pp. 36–37

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils p. 213

- ↑ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp. 200–201

- ↑ Greene and Depew The Philosophy of Biology pp. 128–130

- ↑ Bowler and Morus Making Modern Science pp. 168–169

- ↑ Bowler Evolution: The History of an Idea p. 150

- ↑ Larson Evolution p. 139

- ↑ Larson pp. 126–127

- ↑ Larson pp. 145–147

- ↑ Everhart Oceans of Kansas p. 17

- ↑ The Bone Wars. From Wyoming Tales and Trails Wyoming Tales and Trails.

- ↑ McGowan p. 105

- ↑ Bowler Evolution p. 349

- ↑ Prothero ch. 8

- ↑ Alvarez, LW, Alvarez, W, Asaro, F, and Michel, HV (1980). "Extraterrestrial cause for the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction". Science. 208 (4448): 1095–1108. Bibcode:1980Sci...208.1095A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.126.8496. doi:10.1126/science.208.4448.1095. PMID 17783054. S2CID 16017767.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Garwin, Laura; Tim Lincoln. "A Century of Nature: Twenty-One Discoveries that Changed Science and the World". University of Chicago Press. pp. 3–9. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ Bowler Evolution p. 337

- ↑ Eldredge, Niles and S. J. Gould (1972). "Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism" In T.J.M. Schopf, ed., Models in Paleobiology. San Francisco: Freeman Cooper. pp. 82–115. Reprinted in N. Eldredge Time frames. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1985. Available here "Niles Eldredge Library of Evolution". Archived from the original on 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2009-07-20..

- ↑ Briggs, D. E. G.; Fortey, R. A. (2005). "Wonderful strife: systematics, stem groups, and the phylogenetic signal of the Cambrian radiation" (PDF). Paleobiology. 31 (2 (Supplement)): 94–112. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0094:WSSSGA]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 44066226.

- ↑ Schopf, J. William (June 2000). "Solution to Darwin's dilemma: Discovery of the missing Precambrian record of life". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (13): 6947–53. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.6947S. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.13.6947. PMC 34368. PMID 10860955.

References

- Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: The History of an Idea. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23693-6.

- Bowler, Peter J. (1992). The Earth Encompassed: A History of the Environmental Sciences. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32080-0.

- Bowler, Peter J.; Iwan Rhys Morus (2005). Making Modern Science. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06861-9.

- Desmond, Adrian (1975). "The Discovery of Marine Transgressions and the Explanation of Fossils in Antiquity". American Journal of Science, Volume 275.

- Larson, Edward J. (2004). Evolution: the remarkable history of scientific theory. Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-679-64288-6.

- McGowan, Christopher (2001). The Dragon Seekers. Persus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7382-0282-2.

- Everhart, Michael J. (2005). Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34547-9.

- Greene, Marjorie; David Depew (2004). The Philosophy of Biology: An Episodic History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64371-9.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Caves Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-253-34547-9.

- Robert Hooke (1665) Micrographia The Royal Society

- Palmer, Douglas (2005) Earth Time: Exploring the Deep Past from Victorian England to the Grand Canyon. Wiley, Chichester. ISBN 978-0-470-02221-4

- Rudwick, Martin J.S. (1997). Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73106-3.

- Prothero, Donald .R (2015). The Story of Life in 25 Fossils. Columbia University Press New York. ISBN 978-0-231-53942-5.

- Rudwick, Martin J.S. (1985). The Meaning of Fossils (2nd ed.). The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73103-2.

- Rudwick, Martin J.S. (1985). The Great Devonian Controversy: The Shaping of Scientific Knowledge among Gentlemanly Specialists. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73102-5.

- Rudwick, Martin J.S. (2008). Worlds Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73128-5.

- Zittel, Karl Alfred von (1901). History of geology and palaentology to the end of the Nineteenth Century. Charles Scribner's Sons, London.

- Dong, Zhiming (1992). Dinosaurian Faunas of China (English ed.). Beijing; Berlin; New York: China Ocean Press; Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-52084-9. LCCN 92207835. OCLC 26522845.