| Regular (2D) polygons | |

|---|---|

| Convex | Star |

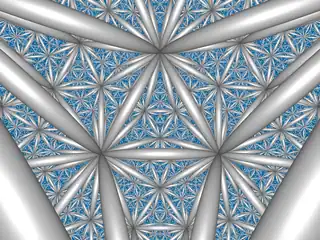

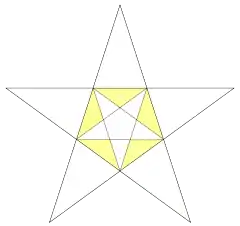

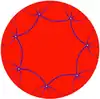

{5} |

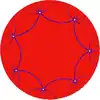

{5/2} |

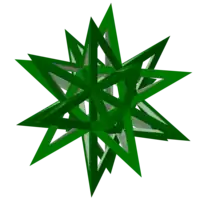

| Regular (3D) polyhedra | |

| Convex | Star |

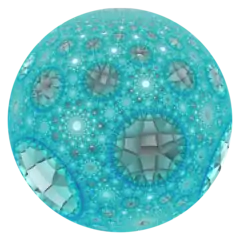

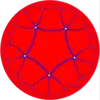

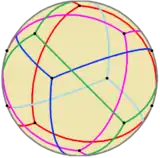

{5,3} |

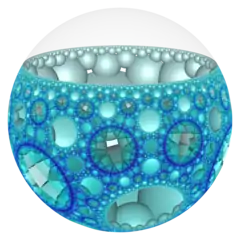

{5/2,5} |

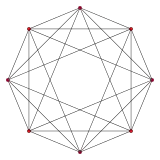

| Regular 4D polytopes | |

| Convex | Star |

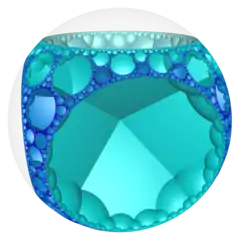

{5,3,3} |

{5/2,5,3} |

| Regular 2D tessellations | |

| Euclidean | Hyperbolic |

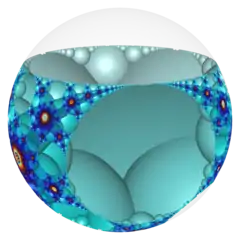

{4,4} |

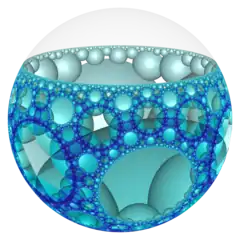

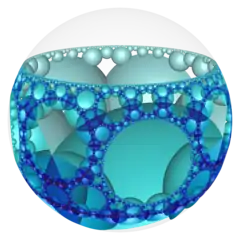

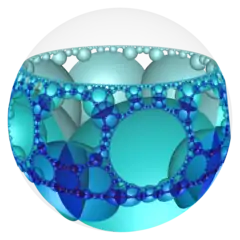

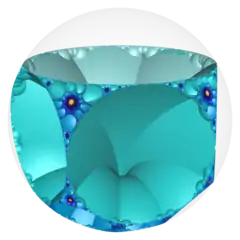

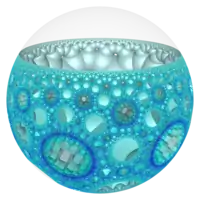

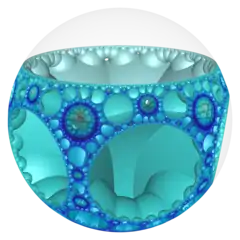

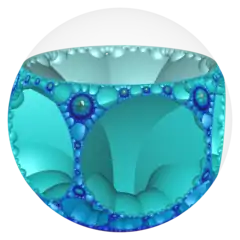

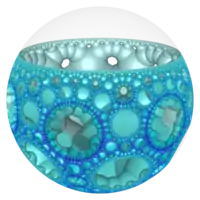

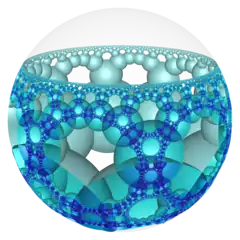

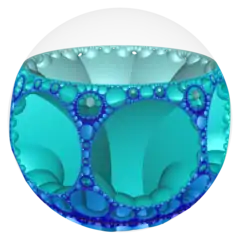

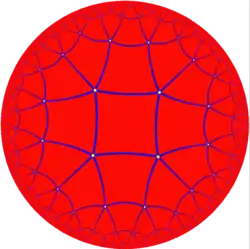

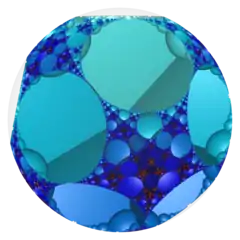

{5,4} |

| Regular 3D tessellations | |

| Euclidean | Hyperbolic |

{4,3,4} |

{5,3,4} |

This article lists the regular polytopes and regular polytope compounds in Euclidean, spherical and hyperbolic spaces.

The Schläfli symbol describes every regular tessellation of an n-sphere, Euclidean and hyperbolic spaces. A Schläfli symbol describing an n-polytope equivalently describes a tessellation of an (n − 1)-sphere. In addition, the symmetry of a regular polytope or tessellation is expressed as a Coxeter group, which Coxeter expressed identically to the Schläfli symbol, except delimiting by square brackets, a notation that is called Coxeter notation. Another related symbol is the Coxeter–Dynkin diagram which represents a symmetry group with no rings, and the represents regular polytope or tessellation with a ring on the first node. For example, the cube has Schläfli symbol {4,3}, and with its octahedral symmetry, [4,3] or ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , it is represented by Coxeter diagram

, it is represented by Coxeter diagram ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

The regular polytopes are grouped by dimension and subgrouped by convex, nonconvex and infinite forms. Nonconvex forms use the same vertices as the convex forms, but have intersecting facets. Infinite forms tessellate a one-lower-dimensional Euclidean space.

Infinite forms can be extended to tessellate a hyperbolic space. Hyperbolic space is like normal space at a small scale, but parallel lines diverge at a distance. This allows vertex figures to have negative angle defects, like making a vertex with seven equilateral triangles and allowing it to lie flat. It cannot be done in a regular plane, but can be at the right scale of a hyperbolic plane.

A more general definition of regular polytopes which do not have simple Schläfli symbols includes regular skew polytopes and regular skew apeirotopes with nonplanar facets or vertex figures.

Overview

This table shows a summary of regular polytope counts by dimension.

Note that the Euclidean and hyperbolic tilings are given one dimension more than what would be expected. This is because of an analogy with finite polytopes: a convex regular n-polytope can be seen as a tessellation of (n−1)-dimensional spherical space. Thus the three regular tilings of the Euclidean plane (by triangles, squares, and hexagons) are listed under dimension three rather than two.

| Dim. | Finite | Euclidean | Hyperbolic | Compounds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compact | Paracompact | ||||||||

| Convex | Star | Skew | Convex | Convex | Star | Convex | Convex | Star | |

| 1 | 1 | none | none | 1 | none | none | none | none | none |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | none | none | |||||

| 3 | 5 | 4 | ? | 3 | 5 | none | |||

| 4 | 6 | 10 | ? | 1 | 4 | none | 11 | 26 | 20 |

| 5 | 3 | none | ? | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | none | none |

| 6 | 3 | none | ? | 1 | none | none | 5 | none | none |

| 7 | 3 | none | ? | 1 | none | none | none | 3 | none |

| 8 | 3 | none | ? | 1 | none | none | none | 6 | none |

| 9+ | 3 | none | ? | 1 | none | none | none | [lower-alpha 1] | none |

There are no Euclidean regular star tessellations in any number of dimensions.

One dimension

|

A Coxeter diagram represent mirror "planes" as nodes, and puts a ring around a node if a point is not on the plane. A dion { }, |

A one-dimensional polytope or 1-polytope is a closed line segment, bounded by its two endpoints. A 1-polytope is regular by definition and is represented by Schläfli symbol { },[1][2] or a Coxeter diagram with a single ringed node, ![]() . Norman Johnson calls it a dion[3] and gives it the Schläfli symbol { }.

. Norman Johnson calls it a dion[3] and gives it the Schläfli symbol { }.

Although trivial as a polytope, it appears as the edges of polygons and other higher dimensional polytopes.[4] It is used in the definition of uniform prisms like Schläfli symbol { }×{p}, or Coxeter diagram ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() as a Cartesian product of a line segment and a regular polygon.[5]

as a Cartesian product of a line segment and a regular polygon.[5]

Two dimensions (polygons)

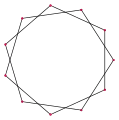

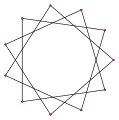

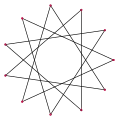

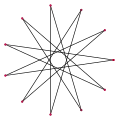

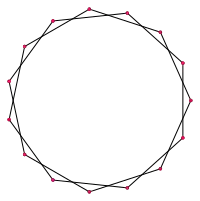

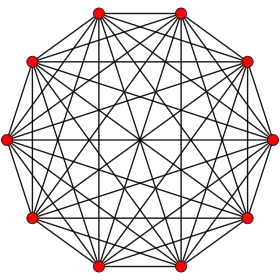

The two-dimensional polytopes are called polygons. Regular polygons are equilateral and cyclic. A p-gonal regular polygon is represented by Schläfli symbol {p}.

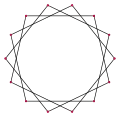

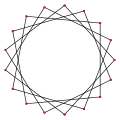

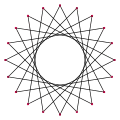

Usually only convex polygons are considered regular, but star polygons, like the pentagram, can also be considered regular. They use the same vertices as the convex forms, but connect in an alternate connectivity which passes around the circle more than once to be completed.

Star polygons should be called nonconvex rather than concave because the intersecting edges do not generate new vertices and all the vertices exist on a circle boundary.

Convex

The Schläfli symbol {p} represents a regular p-gon.

| Name | Triangle (2-simplex) |

Square (2-orthoplex) (2-cube) |

Pentagon (2-pentagonal polytope) |

Hexagon | Heptagon | Octagon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schläfli | {3} | {4} | {5} | {6} | {7} | {8} | |

| Symmetry | D3, [3] | D4, [4] | D5, [5] | D6, [6] | D7, [7] | D8, [8] | |

| Coxeter | |||||||

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Name | Nonagon (Enneagon) |

Decagon | Hendecagon | Dodecagon | Tridecagon | Tetradecagon | |

| Schläfli | {9} | {10} | {11} | {12} | {13} | {14} | |

| Symmetry | D9, [9] | D10, [10] | D11, [11] | D12, [12] | D13, [13] | D14, [14] | |

| Dynkin | |||||||

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Name | Pentadecagon | Hexadecagon | Heptadecagon | Octadecagon | Enneadecagon | Icosagon | ...p-gon |

| Schläfli | {15} | {16} | {17} | {18} | {19} | {20} | {p} |

| Symmetry | D15, [15] | D16, [16] | D17, [17] | D18, [18] | D19, [19] | D20, [20] | Dp, [p] |

| Dynkin | |||||||

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spherical

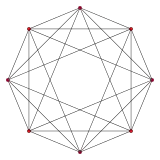

The regular digon {2} can be considered to be a degenerate regular polygon. It can be realized non-degenerately in some non-Euclidean spaces, such as on the surface of a sphere or torus. For example, digon can be realised non-degenerately as a spherical lune. A monogon {1} could also be realised on the sphere as a single point with a great circle through it.[6] However, a monogon is not a valid abstract polytope because its single edge is incident to only one vertex rather than two.

| Name | Monogon | Digon |

|---|---|---|

| Schläfli symbol | {1} | {2} |

| Symmetry | D1, [ ] | D2, [2] |

| Coxeter diagram | ||

| Image |  |

|

Stars

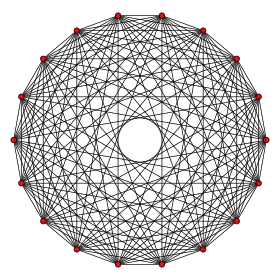

There exist infinitely many regular star polytopes in two dimensions, whose Schläfli symbols consist of rational numbers {n/m}. They are called star polygons and share the same vertex arrangements of the convex regular polygons.

In general, for any natural number n, there are n-pointed star regular polygonal stars with Schläfli symbols {n/m} for all m such that m < n/2 (strictly speaking {n/m}={n/(n−m)}) and m and n are coprime (as such, all stellations of a polygon with a prime number of sides will be regular stars). Cases where m and n are not coprime are called compound polygons.

| Name | Pentagram | Heptagrams | Octagram | Enneagrams | Decagram | ...n-grams | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schläfli | {5/2} | {7/2} | {7/3} | {8/3} | {9/2} | {9/4} | {10/3} | {p/q} |

| Symmetry | D5, [5] | D7, [7] | D8, [8] | D9, [9], | D10, [10] | Dp, [p] | ||

| Coxeter | ||||||||

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{11/2} |

{11/3} |

{11/4} |

{11/5} |

{12/5} |

{13/2} |

{13/3} |

{13/4} |

{13/5} |

{13/6} | |

{14/3} |

{14/5} |

{15/2} |

{15/4} |

{15/7} |

{16/3} |

{16/5} |

{16/7} | |||

{17/2} |

{17/3} |

{17/4} |

{17/5} |

{17/6} |

{17/7} |

{17/8} |

{18/5} |

{18/7} | ||

{19/2} |

{19/3} |

{19/4} |

{19/5} |

{19/6} |

{19/7} |

{19/8} |

{19/9} |

{20/3} |

{20/7} |

{20/9} |

Star polygons that can only exist as spherical tilings, similarly to the monogon and digon, may exist (for example: {3/2}, {5/3}, {5/4}, {7/4}, {9/5}), however these do not appear to have been studied in detail.

There also exist failed star polygons, such as the piangle, which do not cover the surface of a circle finitely many times.[7]

Skew polygons

In 3-dimensional space, a regular skew polygon is called an antiprismatic polygon, with the vertex arrangement of an antiprism, and a subset of edges, zig-zagging between top and bottom polygons.

| Hexagon | Octagon | Decagons | ||

| D3d, [2+,6] | D4d, [2+,8] | D5d, [2+,10] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| {3}#{ } | {4}#{ } | {5}#{ } | {5/2}#{ } | {5/3}#{ } |

|

|

|

|

|

In 4-dimensions a regular skew polygon can have vertices on a Clifford torus and related by a Clifford displacement. Unlike antiprismatic skew polygons, skew polygons on double rotations can include an odd-number of sides.

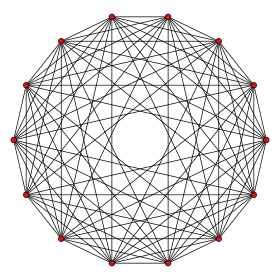

They can be seen in the Petrie polygons of the convex regular 4-polytopes, seen as regular plane polygons in the perimeter of Coxeter plane projection:

| Pentagon | Octagon | Dodecagon | Triacontagon |

|---|---|---|---|

5-cell |

16-cell |

24-cell |

600-cell |

Three dimensions (polyhedra)

In three dimensions, polytopes are called polyhedra:

A regular polyhedron with Schläfli symbol {p,q}, Coxeter diagrams ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , has a regular face type {p}, and regular vertex figure {q}.

, has a regular face type {p}, and regular vertex figure {q}.

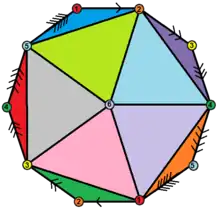

A vertex figure (of a polyhedron) is a polygon, seen by connecting those vertices which are one edge away from a given vertex. For regular polyhedra, this vertex figure is always a regular (and planar) polygon.

Existence of a regular polyhedron {p,q} is constrained by an inequality, related to the vertex figure's angle defect:

By enumerating the permutations, we find five convex forms, four star forms and three plane tilings, all with polygons {p} and {q} limited to: {3}, {4}, {5}, {5/2}, and {6}.

Beyond Euclidean space, there is an infinite set of regular hyperbolic tilings.

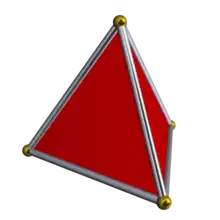

Convex

The five convex regular polyhedra are called the Platonic solids. The vertex figure is given with each vertex count. All these polyhedra have an Euler characteristic (χ) of 2.

| Name | Schläfli {p,q} |

Coxeter |

Image (solid) |

Image (sphere) |

Faces {p} |

Edges | Vertices {q} |

Symmetry | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedron (3-simplex) |

{3,3} |  |

|

4 {3} |

6 | 4 {3} |

Td [3,3] (*332) |

(self) | |

| Hexahedron Cube (3-cube) |

{4,3} |  |

|

6 {4} |

12 | 8 {3} |

Oh [4,3] (*432) |

Octahedron | |

| Octahedron (3-orthoplex) |

{3,4} |  |

|

8 {3} |

12 | 6 {4} |

Oh [4,3] (*432) |

Cube | |

| Dodecahedron | {5,3} |  |

|

12 {5} |

30 | 20 {3} |

Ih [5,3] (*532) |

Icosahedron | |

| Icosahedron | {3,5} |  |

|

20 {3} |

30 | 12 {5} |

Ih [5,3] (*532) |

Dodecahedron |

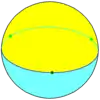

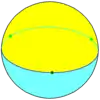

Spherical

In spherical geometry, regular spherical polyhedra (tilings of the sphere) exist that would otherwise be degenerate as polytopes. These are the hosohedra {2,n} and their dual dihedra {n,2}. Coxeter calls these cases "improper" tessellations.[8]

The first few cases (n from 2 to 6) are listed below.

| Name | Schläfli {2,p} |

Coxeter diagram |

Image (sphere) |

Faces {2}π/p |

Edges | Vertices {p} |

Symmetry | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digonal hosohedron | {2,2} |  |

2 {2}π/2 |

2 | 2 {2}π/2 |

D2h [2,2] (*222) |

Self | |

| Trigonal hosohedron | {2,3} |  |

3 {2}π/3 |

3 | 2 {3} |

D3h [2,3] (*322) |

Trigonal dihedron | |

| Square hosohedron | {2,4} |  |

4 {2}π/4 |

4 | 2 {4} |

D4h [2,4] (*422) |

Square dihedron | |

| Pentagonal hosohedron | {2,5} |  |

5 {2}π/5 |

5 | 2 {5} |

D5h [2,5] (*522) |

Pentagonal dihedron | |

| Hexagonal hosohedron | {2,6} |  |

6 {2}π/6 |

6 | 2 {6} |

D6h [2,6] (*622) |

Hexagonal dihedron |

| Name | Schläfli {p,2} |

Coxeter diagram |

Image (sphere) |

Faces {p} |

Edges | Vertices {2} |

Symmetry | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digonal dihedron | {2,2} |  |

2 {2}π/2 |

2 | 2 {2}π/2 |

D2h [2,2] (*222) |

Self | |

| Trigonal dihedron | {3,2} |  |

2 {3} |

3 | 3 {2}π/3 |

D3h [3,2] (*322) |

Trigonal hosohedron | |

| Square dihedron | {4,2} |  |

2 {4} |

4 | 4 {2}π/4 |

D4h [4,2] (*422) |

Square hosohedron | |

| Pentagonal dihedron | {5,2} |  |

2 {5} |

5 | 5 {2}π/5 |

D5h [5,2] (*522) |

Pentagonal hosohedron | |

| Hexagonal dihedron | {6,2} |  |

2 {6} |

6 | 6 {2}π/6 |

D6h [6,2] (*622) |

Hexagonal hosohedron |

Star-dihedra and hosohedra {p/q,2} and {2,p/q} also exist for any star polygon {p/q}.

Stars

The regular star polyhedra are called the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra and there are four of them, based on the vertex arrangements of the dodecahedron {5,3} and icosahedron {3,5}:

As spherical tilings, these star forms overlap the sphere multiple times, called its density, being 3 or 7 for these forms. The tiling images show a single spherical polygon face in yellow.

| Name | Image (skeletonic) |

Image (solid) |

Image (sphere) |

Stellation diagram |

Schläfli {p,q} and Coxeter |

Faces {p} |

Edges | Vertices {q} verf. |

χ | Density | Symmetry | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small stellated dodecahedron |  |

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

{5/2,5} |

12 {5/2} |

30 | 12 {5} |

−6 | 3 | Ih [5,3] (*532) | Great dodecahedron |

| Great dodecahedron |  |

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

{5,5/2} |

12 {5} |

30 | 12 {5/2} |

−6 | 3 | Ih [5,3] (*532) | Small stellated dodecahedron |

| Great stellated dodecahedron |  |

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

{5/2,3} |

12 {5/2} |

30 | 20 {3} |

2 | 7 | Ih [5,3] (*532) | Great icosahedron |

| Great icosahedron |  |

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

{3,5/2} |

20 {3} |

30 | 12 {5/2} |

2 | 7 | Ih [5,3] (*532) | Great stellated dodecahedron |

There are infinitely many failed star polyhedra. These are also spherical tilings with star polygons in their Schläfli symbols, but they do not cover a sphere finitely many times. Some examples are {5/2,4}, {5/2,9}, {7/2,3}, {5/2,5/2}, {7/2,7/3}, {4,5/2}, and {3,7/3}.

Skew polyhedra

Regular skew polyhedra are generalizations to the set of regular polyhedron which include the possibility of nonplanar vertex figures.

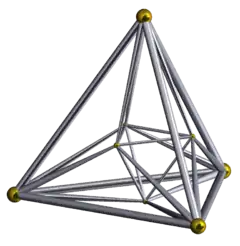

For 4-dimensional skew polyhedra, Coxeter offered a modified Schläfli symbol {l,m|n} for these figures, with {l,m} implying the vertex figure, m l-gons around a vertex, and n-gonal holes. Their vertex figures are skew polygons, zig-zagging between two planes.

The regular skew polyhedra, represented by {l,m|n}, follow this equation:

- 2 sin(π/l) sin(π/m) = cos(π/n)

Four of them can be seen in 4-dimensions as a subset of faces of four regular 4-polytopes, sharing the same vertex arrangement and edge arrangement:

|

|

|

|

| {4, 6 | 3} | {6, 4 | 3} | {4, 8 | 3} | {8, 4 | 3} |

|---|

Four dimensions

Regular 4-polytopes with Schläfli symbol have cells of type , faces of type , edge figures , and vertex figures .

- A vertex figure (of a 4-polytope) is a polyhedron, seen by the arrangement of neighboring vertices around a given vertex. For regular 4-polytopes, this vertex figure is a regular polyhedron.

- An edge figure is a polygon, seen by the arrangement of faces around an edge. For regular 4-polytopes, this edge figure will always be a regular polygon.

The existence of a regular 4-polytope is constrained by the existence of the regular polyhedra . A suggested name for 4-polytopes is "polychoron".[9]

Each will exist in a space dependent upon this expression:

-

- : Hyperspherical 3-space honeycomb or 4-polytope

- : Euclidean 3-space honeycomb

- : Hyperbolic 3-space honeycomb

These constraints allow for 21 forms: 6 are convex, 10 are nonconvex, one is a Euclidean 3-space honeycomb, and 4 are hyperbolic honeycombs.

The Euler characteristic for convex 4-polytopes is zero:

Convex

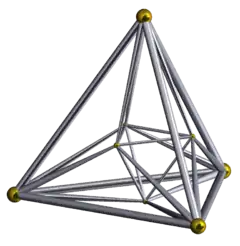

The 6 convex regular 4-polytopes are shown in the table below. All these 4-polytopes have an Euler characteristic (χ) of 0.

| Name |

Schläfli {p,q,r} |

Coxeter |

Cells {p,q} |

Faces {p} |

Edges {r} |

Vertices {q,r} |

Dual {r,q,p} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-cell (4-simplex) |

{3,3,3} | 5 {3,3} |

10 {3} |

10 {3} |

5 {3,3} |

(self) | |

| 8-cell (4-cube) (Tesseract) |

{4,3,3} | 8 {4,3} |

24 {4} |

32 {3} |

16 {3,3} |

16-cell | |

| 16-cell (4-orthoplex) |

{3,3,4} | 16 {3,3} |

32 {3} |

24 {4} |

8 {3,4} |

Tesseract | |

| 24-cell | {3,4,3} | 24 {3,4} |

96 {3} |

96 {3} |

24 {4,3} |

(self) | |

| 120-cell | {5,3,3} | 120 {5,3} |

720 {5} |

1200 {3} |

600 {3,3} |

600-cell | |

| 600-cell | {3,3,5} | 600 {3,3} |

1200 {3} |

720 {5} |

120 {3,5} |

120-cell |

| 5-cell | 8-cell | 16-cell | 24-cell | 120-cell | 600-cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| {3,3,3} | {4,3,3} | {3,3,4} | {3,4,3} | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| Wireframe (Petrie polygon) skew orthographic projections | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Solid orthographic projections | |||||

tetrahedral envelope (cell/ vertex-centered) |

cubic envelope (cell-centered) |

cubic envelope (cell-centered) |

cuboctahedral envelope (cell-centered) |

truncated rhombic triacontahedron envelope (cell-centered) |

Pentakis icosidodecahedral envelope (vertex-centered) |

| Wireframe Schlegel diagrams (Perspective projection) | |||||

(cell-centered) |

(cell-centered) |

(cell-centered) |

(cell-centered) |

(cell-centered) |

(vertex-centered) |

| Wireframe stereographic projections (Hyperspherical) | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spherical

Di-4-topes and hoso-4-topes exist as regular tessellations of the 3-sphere.

Regular di-4-topes (2 facets) include: {3,3,2}, {3,4,2}, {4,3,2}, {5,3,2}, {3,5,2}, {p,2,2}, and their hoso-4-tope duals (2 vertices): {2,3,3}, {2,4,3}, {2,3,4}, {2,3,5}, {2,5,3}, {2,2,p}. 4-polytopes of the form {2,p,2} are the same as {2,2,p}. There are also the cases {p,2,q} which have dihedral cells and hosohedral vertex figures.

| Schläfli {2,p,q} |

Coxeter |

Cells {2,p}π/q |

Faces {2}π/p,π/q |

Edges | Vertices | Vertex figure {p,q} |

Symmetry | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| {2,3,3} | 4 {2,3}π/3  |

6 {2}π/3,π/3 |

4 | 2 | {3,3} |

[2,3,3] | {3,3,2} | |

| {2,4,3} | 6 {2,4}π/3  |

12 {2}π/4,π/3 |

8 | 2 | {4,3} |

[2,4,3] | {3,4,2} | |

| {2,3,4} | 8 {2,3}π/4  |

12 {2}π/3,π/4 |

6 | 2 | {3,4} |

[2,4,3] | {4,3,2} | |

| {2,5,3} | 12 {2,5}π/3  |

30 {2}π/5,π/3 |

20 | 2 | {5,3} |

[2,5,3] | {3,5,2} | |

| {2,3,5} | 20 {2,3}π/5  |

30 {2}π/3,π/5 |

12 | 2 | {3,5} |

[2,5,3] | {5,3,2} |

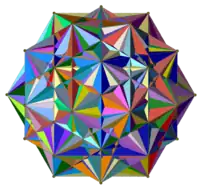

Stars

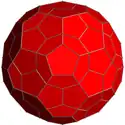

There are ten regular star 4-polytopes, which are called the Schläfli–Hess 4-polytopes. Their vertices are based on the convex 120-cell {5,3,3} and 600-cell {3,3,5}.

Ludwig Schläfli found four of them and skipped the last six because he would not allow forms that failed the Euler characteristic on cells or vertex figures (for zero-hole tori: F+V−E=2). Edmund Hess (1843–1903) completed the full list of ten in his German book Einleitung in die Lehre von der Kugelteilung mit besonderer Berücksichtigung ihrer Anwendung auf die Theorie der Gleichflächigen und der gleicheckigen Polyeder (1883).

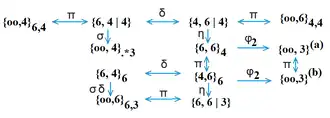

There are 4 unique edge arrangements and 7 unique face arrangements from these 10 regular star 4-polytopes, shown as orthogonal projections:

| Name |

Wireframe | Solid | Schläfli {p, q, r} Coxeter |

Cells {p, q} |

Faces {p} |

Edges {r} |

Vertices {q, r} |

Density | χ | Symmetry group | Dual {r, q,p} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Icosahedral 120-cell (faceted 600-cell) |

|

|

{3,5,5/2} |

120 {3,5} |

1200 {3} |

720 {5/2} |

120 {5,5/2} |

4 | 480 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Small stellated 120-cell |

| Small stellated 120-cell |  |

|

{5/2,5,3} |

120 {5/2,5} |

720 {5/2} |

1200 {3} |

120 {5,3} |

4 | −480 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Icosahedral 120-cell |

| Great 120-cell |  |

|

{5,5/2,5} |

120 {5,5/2} |

720 {5} |

720 {5} |

120 {5/2,5} |

6 | 0 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Self-dual |

| Grand 120-cell |  |

|

{5,3,5/2} |

120 {5,3} |

720 {5} |

720 {5/2} |

120 {3,5/2} |

20 | 0 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Great stellated 120-cell |

| Great stellated 120-cell |  |

|

{5/2,3,5} |

120 {5/2,3} |

720 {5/2} |

720 {5} |

120 {3,5} |

20 | 0 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Grand 120-cell |

| Grand stellated 120-cell |  |

|

{5/2,5,5/2} |

120 {5/2,5} |

720 {5/2} |

720 {5/2} |

120 {5,5/2} |

66 | 0 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Self-dual |

| Great grand 120-cell |  |

|

{5,5/2,3} |

120 {5,5/2} |

720 {5} |

1200 {3} |

120 {5/2,3} |

76 | −480 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Great icosahedral 120-cell |

| Great icosahedral 120-cell (great faceted 600-cell) |

|

|

{3,5/2,5} |

120 {3,5/2} |

1200 {3} |

720 {5} |

120 {5/2,5} |

76 | 480 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Great grand 120-cell |

| Grand 600-cell |  |

|

{3,3,5/2} |

600 {3,3} |

1200 {3} |

720 {5/2} |

120 {3,5/2} |

191 | 0 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Great grand stellated 120-cell |

| Great grand stellated 120-cell |  |

|

{5/2,3,3} |

120 {5/2,3} |

720 {5/2} |

1200 {3} |

600 {3,3} |

191 | 0 | H4 [5,3,3] |

Grand 600-cell |

There are 4 failed potential regular star 4-polytopes permutations: {3,5/2,3}, {4,3,5/2}, {5/2,3,4}, {5/2,3,5/2}. Their cells and vertex figures exist, but they do not cover a hypersphere with a finite number of repetitions.

Five and more dimensions

In five dimensions, a regular polytope can be named as where is the 4-face type, is the cell type, is the face type, and is the face figure, is the edge figure, and is the vertex figure.

- A vertex figure (of a 5-polytope) is a 4-polytope, seen by the arrangement of neighboring vertices to each vertex.

- An edge figure (of a 5-polytope) is a polyhedron, seen by the arrangement of faces around each edge.

- A face figure (of a 5-polytope) is a polygon, seen by the arrangement of cells around each face.

A regular 5-polytope exists only if and are regular 4-polytopes.

The space it fits in is based on the expression:

-

- : Spherical 4-space tessellation or 5-space polytope

- : Euclidean 4-space tessellation

- : hyperbolic 4-space tessellation

Enumeration of these constraints produce 3 convex polytopes, zero nonconvex polytopes, 3 4-space tessellations, and 5 hyperbolic 4-space tessellations. There are no non-convex regular polytopes in five dimensions or higher.

Convex

In dimensions 5 and higher, there are only three kinds of convex regular polytopes.[10]

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p1,...,pn−1} |

Coxeter | k-faces | Facet type |

Vertex figure |

Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-simplex | {3n−1} | {3n−2} | {3n−2} | Self-dual | ||

| n-cube | {4,3n−2} | {4,3n−3} | {3n−2} | n-orthoplex | ||

| n-orthoplex | {3n−2,4} | {3n−2} | {3n−3,4} | n-cube |

There are also improper cases where some numbers in the Schläfli symbol are 2. For example, {p,q,r,...2} is an improper regular spherical polytope whenever {p,q,r...} is a regular spherical polytope, and {2,...p,q,r} is an improper regular spherical polytope whenever {...p,q,r} is a regular spherical polytope. Such polytopes may also be used as facets, yielding forms such as {p,q,...2...y,z}.

5 dimensions

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p,q,r,s} Coxeter |

Facets {p,q,r} |

Cells {p,q} |

Faces {p} |

Edges | Vertices | Face figure {s} |

Edge figure {r,s} |

Vertex figure {q,r,s} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-simplex | {3,3,3,3} | 6 {3,3,3} | 15 {3,3} | 20 {3} | 15 | 6 | {3} | {3,3} | {3,3,3} |

| 5-cube | {4,3,3,3} | 10 {4,3,3} | 40 {4,3} | 80 {4} | 80 | 32 | {3} | {3,3} | {3,3,3} |

| 5-orthoplex | {3,3,3,4} | 32 {3,3,3} | 80 {3,3} | 80 {3} | 40 | 10 | {4} | {3,4} | {3,3,4} |

5-simplex |

5-cube |

5-orthoplex |

6 dimensions

| Name | Schläfli | Vertices | Edges | Faces | Cells | 4-faces | 5-faces | χ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-simplex | {3,3,3,3,3} | 7 | 21 | 35 | 35 | 21 | 7 | 0 |

| 6-cube | {4,3,3,3,3} | 64 | 192 | 240 | 160 | 60 | 12 | 0 |

| 6-orthoplex | {3,3,3,3,4} | 12 | 60 | 160 | 240 | 192 | 64 | 0 |

6-simplex |

6-cube |

6-orthoplex |

7 dimensions

| Name | Schläfli | Vertices | Edges | Faces | Cells | 4-faces | 5-faces | 6-faces | χ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-simplex | {3,3,3,3,3,3} | 8 | 28 | 56 | 70 | 56 | 28 | 8 | 2 |

| 7-cube | {4,3,3,3,3,3} | 128 | 448 | 672 | 560 | 280 | 84 | 14 | 2 |

| 7-orthoplex | {3,3,3,3,3,4} | 14 | 84 | 280 | 560 | 672 | 448 | 128 | 2 |

7-simplex |

7-cube |

7-orthoplex |

8 dimensions

| Name | Schläfli | Vertices | Edges | Faces | Cells | 4-faces | 5-faces | 6-faces | 7-faces | χ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-simplex | {3,3,3,3,3,3,3} | 9 | 36 | 84 | 126 | 126 | 84 | 36 | 9 | 0 |

| 8-cube | {4,3,3,3,3,3,3} | 256 | 1024 | 1792 | 1792 | 1120 | 448 | 112 | 16 | 0 |

| 8-orthoplex | {3,3,3,3,3,3,4} | 16 | 112 | 448 | 1120 | 1792 | 1792 | 1024 | 256 | 0 |

8-simplex |

8-cube |

8-orthoplex |

9 dimensions

| Name | Schläfli | Vertices | Edges | Faces | Cells | 4-faces | 5-faces | 6-faces | 7-faces | 8-faces | χ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9-simplex | {38} | 10 | 45 | 120 | 210 | 252 | 210 | 120 | 45 | 10 | 2 |

| 9-cube | {4,37} | 512 | 2304 | 4608 | 5376 | 4032 | 2016 | 672 | 144 | 18 | 2 |

| 9-orthoplex | {37,4} | 18 | 144 | 672 | 2016 | 4032 | 5376 | 4608 | 2304 | 512 | 2 |

9-simplex |

9-cube |

9-orthoplex |

10 dimensions

| Name | Schläfli | Vertices | Edges | Faces | Cells | 4-faces | 5-faces | 6-faces | 7-faces | 8-faces | 9-faces | χ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-simplex | {39} | 11 | 55 | 165 | 330 | 462 | 462 | 330 | 165 | 55 | 11 | 0 |

| 10-cube | {4,38} | 1024 | 5120 | 11520 | 15360 | 13440 | 8064 | 3360 | 960 | 180 | 20 | 0 |

| 10-orthoplex | {38,4} | 20 | 180 | 960 | 3360 | 8064 | 13440 | 15360 | 11520 | 5120 | 1024 | 0 |

10-simplex |

10-cube |

10-orthoplex |

...

Non-convex

There are no non-convex regular polytopes in five dimensions or higher, excluding hosotopes formed from lower-dimensional non-convex regular polytopes.

Regular projective polytopes

A projective regular (n+1)-polytope exists when an original regular n-spherical tessellation, {p,q,...}, is centrally symmetric. Such a polytope is named hemi-{p,q,...}, and contain half as many elements. Coxeter gives a symbol {p,q,...}/2, while McMullen writes {p,q,...}h/2 with h as the coxeter number.[11]

Even-sided regular polygons have hemi-2n-gon projective polygons, {2p}/2.

There are 4 regular projective polyhedra related to 4 of 5 Platonic solids.

The hemi-cube and hemi-octahedron generalize as hemi-n-cubes and hemi-n-orthoplexes in any dimensions.

Regular projective polyhedra

| Name | Coxeter McMullen | Image | Faces | Edges | Vertices | χ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemi-cube | {4,3}/2 {4,3}3 |

| 3 | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| Hemi-octahedron | {3,4}/2 {3,4}3 |

| 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Hemi-dodecahedron | {5,3}/2 {5,3}5 |

| 6 | 15 | 10 | 1 |

| Hemi-icosahedron | {3,5}/2 {3,5}5 |

| 10 | 15 | 6 | 1 |

Regular projective 4-polytopes

In 4-dimensions 5 of 6 convex regular 4-polytopes generate projective 4-polytopes. The 3 special cases are hemi-24-cell, hemi-600-cell, and hemi-120-cell.

| Name | Coxeter symbol | McMullen Symbol | Cells | Faces | Edges | Vertices | χ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemi-tesseract | {4,3,3}/2 | {4,3,3}4 | 4 | 12 | 16 | 8 | 0 |

| Hemi-16-cell | {3,3,4}/2 | {3,3,4}4 | 8 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| Hemi-24-cell | {3,4,3}/2 | {3,4,3}6 | 12 | 48 | 48 | 12 | 0 |

| Hemi-120-cell | {5,3,3}/2 | {5,3,3}15 | 60 | 360 | 600 | 300 | 0 |

| Hemi-600-cell | {3,3,5}/2 | {3,3,5}15 | 300 | 600 | 360 | 60 | 0 |

Regular projective 5-polytopes

There are only 2 convex regular projective hemi-polytopes in dimensions 5 or higher: they are the hemi versions of the regular hypercube and orthoplex. They are tabulated below in dimension 5, for example:

| Name | Schläfli | 4-faces | Cells | Faces | Edges | Vertices | χ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hemi-penteract | {4,3,3,3}/2 | 5 | 20 | 40 | 40 | 16 | 1 |

| hemi-pentacross | {3,3,3,4}/2 | 16 | 40 | 40 | 20 | 5 | 1 |

Apeirotopes

An apeirotope or infinite polytope is a polytope which has infinitely many facets. An n-apeirotope is an infinite n-polytope: a 2-apeirotope or apeirogon is an infinite polygon, a 3-apeirotope or apeirohedron is an infinite polyhedron, etc.

There are two main geometric classes of apeirotope:[12]

- Regular honeycombs in n dimensions, which completely fill an n-dimensional space.

- Regular skew apeirotopes, comprising an n-dimensional manifold in a higher space.

One dimension (apeirogons)

The straight apeirogon is a regular tessellation of the line, subdividing it into infinitely many equal segments. It has infinitely many vertices and edges. Its Schläfli symbol is {∞}, and Coxeter diagram ![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

...![]() ...

...

It exists as the limit of the p-gon as p tends to infinity, as follows:

| Name | Monogon | Digon | Triangle | Square | Pentagon | Hexagon | Heptagon | p-gon | Apeirogon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schläfli | {1} | {2} | {3} | {4} | {5} | {6} | {7} | {p} | {∞} |

| Symmetry | D1, [ ] | D2, [2] | D3, [3] | D4, [4] | D5, [5] | D6, [6] | D7, [7] | [p] | |

| Coxeter | |||||||||

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

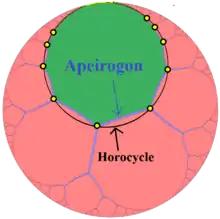

Apeirogons in the hyperbolic plane, most notably the regular apeirogon, {∞}, can have a curvature just like finite polygons of the Euclidean plane, with the vertices circumscribed by horocycles or hypercycles rather than circles.

Regular apeirogons that are scaled to converge at infinity have the symbol {∞} and exist on horocycles, while more generally they can exist on hypercycles.

| {∞} | {πi/λ} |

|---|---|

Apeirogon on horocycle |

Apeirogon on hypercycle |

Above are two regular hyperbolic apeirogons in the Poincaré disk model, the right one shows perpendicular reflection lines of divergent fundamental domains, separated by length λ.

Skew apeirogons

A skew apeirogon in two dimensions forms a zig-zag line in the plane. If the zig-zag is even and symmetrical, then the apeirogon is regular.

Skew apeirogons can be constructed in any number of dimensions. In three dimensions, a regular skew apeirogon traces out a helical spiral and may be either left- or right-handed.

| 2-dimensions | 3-dimensions |

|---|---|

Zig-zag apeirogon |

Helix apeirogon |

Two dimensions (apeirohedra)

Euclidean tilings

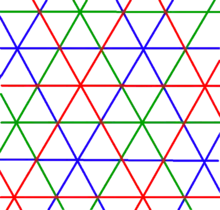

There are three regular tessellations of the plane. All three have an Euler characteristic (χ) of 0.

| Name | Square tiling (quadrille) |

Triangular tiling (deltille) |

Hexagonal tiling (hextille) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | p4m, [4,4], (*442) | p6m, [6,3], (*632) | |

| Schläfli {p,q} | {4,4} | {3,6} | {6,3} |

| Coxeter diagram | |||

| Image |  |

|

|

There are two improper regular tilings: {∞,2}, an apeirogonal dihedron, made from two apeirogons, each filling half the plane; and secondly, its dual, {2,∞}, an apeirogonal hosohedron, seen as an infinite set of parallel lines.

{∞,2}, |

{2,∞}, |

Euclidean star-tilings

There are no regular plane tilings of star polygons. There are many enumerations that fit in the plane (1/p + 1/q = 1/2), like {8/3,8}, {10/3,5}, {5/2,10}, {12/5,12}, etc., but none repeat periodically.

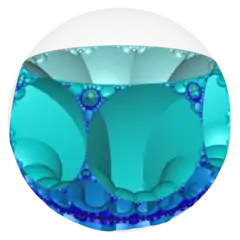

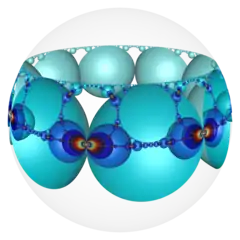

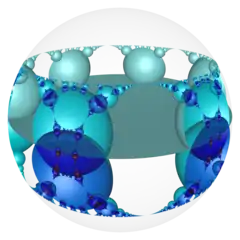

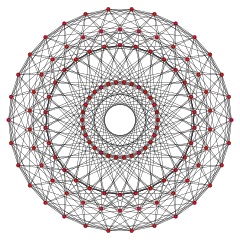

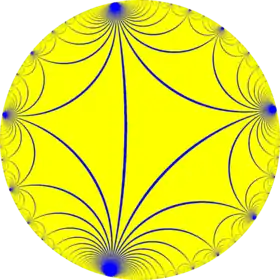

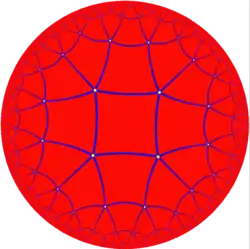

Hyperbolic tilings

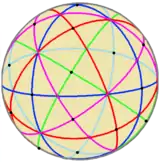

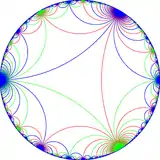

Tessellations of hyperbolic 2-space are hyperbolic tilings. There are infinitely many regular tilings in H2. As stated above, every positive integer pair {p,q} such that 1/p + 1/q < 1/2 gives a hyperbolic tiling. In fact, for the general Schwarz triangle (p, q, r) the same holds true for 1/p + 1/q + 1/r < 1.

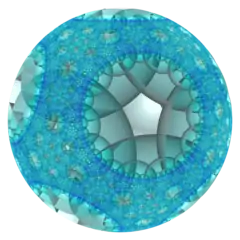

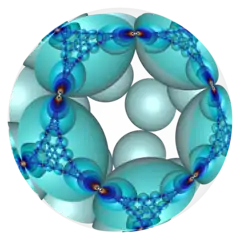

There are a number of different ways to display the hyperbolic plane, including the Poincaré disc model which maps the plane into a circle, as shown below. It should be recognized that all of the polygon faces in the tilings below are equal-sized and only appear to get smaller near the edges due to the projection applied, very similar to the effect of a camera fisheye lens.

There are infinitely many flat regular 3-apeirotopes (apeirohedra) as regular tilings of the hyperbolic plane, of the form {p,q}, with p+q<pq/2. (previously listed above as tessellations)

- {3,7}, {3,8}, {3,9} ... {3,∞}

- {4,5}, {4,6}, {4,7} ... {4,∞}

- {5,4}, {5,5}, {5,6} ... {5,∞}

- {6,4}, {6,5}, {6,6} ... {6,∞}

- {7,3}, {7,4}, {7,5} ... {7,∞}

- {8,3}, {8,4}, {8,5} ... {8,∞}

- {9,3}, {9,4}, {9,5} ... {9,∞}

- ...

- {∞,3}, {∞,4}, {∞,5} ... {∞,∞}

A sampling:

| Regular hyperbolic tiling table | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical (improper/Platonic)/Euclidean/hyperbolic (Poincaré disc: compact/paracompact/noncompact) tessellations with their Schläfli symbol | |||||||||||

| p \ q | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ... | ∞ | ... | iπ/λ |

| 2 |  {2,2} |

{2,3} |

{2,4} |

{2,5} |

{2,6} |

{2,7} |

{2,8} |

{2,∞} |

{2,iπ/λ} | ||

| 3 |  {3,2} |

(tetrahedron) {3,3} |

(octahedron) {3,4} |

(icosahedron) {3,5} |

(deltille) {3,6} |

{3,7} |

{3,8} |

{3,∞} |

{3,iπ/λ} | ||

| 4 |  {4,2} |

(cube) {4,3} |

(quadrille) {4,4} |

{4,5} |

{4,6} |

{4,7} |

{4,8} |

{4,∞} |

{4,iπ/λ} | ||

| 5 |  {5,2} |

(dodecahedron) {5,3} |

{5,4} |

{5,5} |

{5,6} |

{5,7} |

{5,8} |

{5,∞} |

{5,iπ/λ} | ||

| 6 |  {6,2} |

(hextille) {6,3} |

{6,4} |

{6,5} |

{6,6} |

{6,7} |

{6,8} |

{6,∞} |

{6,iπ/λ} | ||

| 7 | {7,2} |

{7,3} |

{7,4} |

{7,5} |

{7,6} |

{7,7} |

{7,8} |

{7,∞} |

{7,iπ/λ} | ||

| 8 | {8,2} |

{8,3} |

{8,4} |

{8,5} |

{8,6} |

{8,7} |

{8,8} |

{8,∞} |

{8,iπ/λ} | ||

| ... | |||||||||||

| ∞ |  {∞,2} |

{∞,3} |

{∞,4} |

{∞,5} |

{∞,6} |

{∞,7} |

{∞,8} |

{∞,∞} |

{∞,iπ/λ} | ||

| ... | |||||||||||

| iπ/λ |  {iπ/λ,2} |

{iπ/λ,3} |

{iπ/λ,4} |

{iπ/λ,5} |

{iπ/λ,6} |

{iπ/λ,7} |

{iπ/λ,8} |

{iπ/λ,∞} |

{iπ/λ, iπ/λ} | ||

The tilings {p, ∞} have ideal vertices, on the edge of the Poincaré disc model. Their duals {∞, p} have ideal apeirogonal faces, meaning that they are inscribed in horocycles. One could go further (as is done in the table above) and find tilings with ultra-ideal vertices, outside the Poincaré disc, which are dual to tiles inscribed in hypercycles; in what is symbolised {p, iπ/λ} above, infinitely many tiles still fit around each ultra-ideal vertex.[13] (Parallel lines in extended hyperbolic space meet at an ideal point; ultraparallel lines meet at an ultra-ideal point.)[14]

Hyperbolic star-tilings

There are 2 infinite forms of hyperbolic tilings whose faces or vertex figures are star polygons: {m/2, m} and their duals {m, m/2} with m = 7, 9, 11, .... The {m/2, m} tilings are stellations of the {m, 3} tilings while the {m, m/2} dual tilings are facetings of the {3, m} tilings and greatenings of the {m, 3} tilings.

The patterns {m/2, m} and {m, m/2} continue for odd m < 7 as polyhedra: when m = 5, we obtain the small stellated dodecahedron and great dodecahedron, and when m = 3, the case degenerates to a tetrahedron. The other two Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra (the great stellated dodecahedron and great icosahedron) do not have regular hyperbolic tiling analogues. If m is even, depending on how we choose to define {m/2}, we can either obtain degenerate double covers of other tilings or compound tilings.

| Name | Schläfli | Coxeter diagram | Image | Face type {p} |

Vertex figure {q} |

Density | Symmetry | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order-7 heptagrammic tiling | {7/2,7} |  |

{7/2} |

{7} |

3 | *732 [7,3] |

Heptagrammic-order heptagonal tiling | |

| Heptagrammic-order heptagonal tiling | {7,7/2} |  |

{7} |

{7/2} |

3 | *732 [7,3] |

Order-7 heptagrammic tiling | |

| Order-9 enneagrammic tiling | {9/2,9} |  |

{9/2} |

{9} |

3 | *932 [9,3] |

Enneagrammic-order enneagonal tiling | |

| Enneagrammic-order enneagonal tiling | {9,9/2} |  |

{9} |

{9/2} |

3 | *932 [9,3] |

Order-9 enneagrammic tiling | |

| Order-11 hendecagrammic tiling | {11/2,11} |  |

{11/2} |

{11} |

3 | *11.3.2 [11,3] |

Hendecagrammic-order hendecagonal tiling | |

| Hendecagrammic-order hendecagonal tiling | {11,11/2} |  |

{11} |

{11/2} |

3 | *11.3.2 [11,3] |

Order-11 hendecagrammic tiling | |

| Order-p p-grammic tiling | {p/2,p} | {p/2} | {p} | 3 | *p32 [p,3] |

p-grammic-order p-gonal tiling | ||

| p-grammic-order p-gonal tiling | {p,p/2} | {p} | {p/2} | 3 | *p32 [p,3] |

Order-p p-grammic tiling |

Skew apeirohedra in Euclidean 3-space

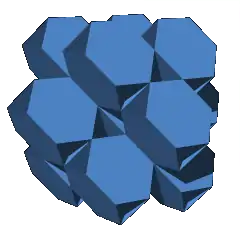

There are three regular skew apeirohedra in Euclidean 3-space, with regular skew polygon vertex figures.[15][16][17] They share the same vertex arrangement and edge arrangement of 3 convex uniform honeycombs.

- 6 squares around each vertex: {4,6|4}

- 4 hexagons around each vertex: {6,4|4}

- 6 hexagons around each vertex: {6,6|3}

| Regular skew polyhedra | ||

|---|---|---|

{4,6|4} |

{6,4|4} |

{6,6|3} |

There are thirty regular apeirohedra in Euclidean 3-space.[19] These include those listed above, as well as 8 other "pure" apeirohedra, all related to the cubic honeycomb, {4,3,4}, with others having skew polygon faces: {6,6}4, {4,6}4, {6,4}6, {∞,3}a, {∞,3}b, {∞,4}.*3, {∞,4}6,4, {∞,6}4,4, and {∞,6}6,3.

Skew apeirohedra in hyperbolic 3-space

There are 31 regular skew apeirohedra in hyperbolic 3-space:[20]

- 14 are compact: {8,10|3}, {10,8|3}, {10,4|3}, {4,10|3}, {6,4|5}, {4,6|5}, {10,6|3}, {6,10|3}, {8,8|3}, {6,6|4}, {10,10|3},{6,6|5}, {8,6|3}, and {6,8|3}.

- 17 are paracompact: {12,10|3}, {10,12|3}, {12,4|3}, {4,12|3}, {6,4|6}, {4,6|6}, {8,4|4}, {4,8|4}, {12,6|3}, {6,12|3}, {12,12|3}, {6,6|6}, {8,6|4}, {6,8|4}, {12,8|3}, {8,12|3}, and {8,8|4}.

Three dimensions (4-apeirotopes)

Tessellations of Euclidean 3-space

There is only one non-degenerate regular tessellation of 3-space (honeycombs), {4, 3, 4}:[21]

| Name | Schläfli {p,q,r} |

Coxeter |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Edge figure {r} |

Vertex figure {q,r} |

χ | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic honeycomb | {4,3,4} | {4,3} | {4} | {4} | {3,4} | 0 | Self-dual |

Improper tessellations of Euclidean 3-space

There are six improper regular tessellations, pairs based on the three regular Euclidean tilings. Their cells and vertex figures are all regular hosohedra {2,n}, dihedra, {n,2}, and Euclidean tilings. These improper regular tilings are constructionally related to prismatic uniform honeycombs by truncation operations. They are higher-dimensional analogues of the order-2 apeirogonal tiling and apeirogonal hosohedron.

| Schläfli {p,q,r} |

Coxeter diagram |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Edge figure {r} |

Vertex figure {q,r} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| {2,4,4} | {2,4} | {2} | {4} | {4,4} | |

| {2,3,6} | {2,3} | {2} | {6} | {3,6} | |

| {2,6,3} | {2,6} | {2} | {3} | {6,3} | |

| {4,4,2} | {4,4} | {4} | {2} | {4,2} | |

| {3,6,2} | {3,6} | {3} | {2} | {6,2} | |

| {6,3,2} | {6,3} | {6} | {2} | {3,2} |

Tessellations of hyperbolic 3-space

There are ten flat regular honeycombs of hyperbolic 3-space:[22] (previously listed above as tessellations)

- 4 are compact: {3,5,3}, {4,3,5}, {5,3,4}, and {5,3,5}

- while 6 are paracompact: {3,3,6}, {6,3,3}, {3,4,4}, {4,4,3}, {3,6,3}, {4,3,6}, {6,3,4}, {4,4,4}, {5,3,6}, {6,3,5}, and {6,3,6}.

| ||||

|

Tessellations of hyperbolic 3-space can be called hyperbolic honeycombs. There are 15 hyperbolic honeycombs in H3, 4 compact and 11 paracompact.

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p,q,r} |

Coxeter |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Edge figure {r} |

Vertex figure {q,r} |

χ | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Icosahedral honeycomb | {3,5,3} | {3,5} | {3} | {3} | {5,3} | 0 | Self-dual | |

| Order-5 cubic honeycomb | {4,3,5} | {4,3} | {4} | {5} | {3,5} | 0 | {5,3,4} | |

| Order-4 dodecahedral honeycomb | {5,3,4} | {5,3} | {5} | {4} | {3,4} | 0 | {4,3,5} | |

| Order-5 dodecahedral honeycomb | {5,3,5} | {5,3} | {5} | {5} | {3,5} | 0 | Self-dual |

There are also 11 paracompact H3 honeycombs (those with infinite (Euclidean) cells and/or vertex figures): {3,3,6}, {6,3,3}, {3,4,4}, {4,4,3}, {3,6,3}, {4,3,6}, {6,3,4}, {4,4,4}, {5,3,6}, {6,3,5}, and {6,3,6}.

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p,q,r} |

Coxeter |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Edge figure {r} |

Vertex figure {q,r} |

χ | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order-6 tetrahedral honeycomb | {3,3,6} | {3,3} | {3} | {6} | {3,6} | 0 | {6,3,3} | |

| Hexagonal tiling honeycomb | {6,3,3} | {6,3} | {6} | {3} | {3,3} | 0 | {3,3,6} | |

| Order-4 octahedral honeycomb | {3,4,4} | {3,4} | {3} | {4} | {4,4} | 0 | {4,4,3} | |

| Square tiling honeycomb | {4,4,3} | {4,4} | {4} | {3} | {4,3} | 0 | {3,3,4} | |

| Triangular tiling honeycomb | {3,6,3} | {3,6} | {3} | {3} | {6,3} | 0 | Self-dual | |

| Order-6 cubic honeycomb | {4,3,6} | {4,3} | {4} | {4} | {3,6} | 0 | {6,3,4} | |

| Order-4 hexagonal tiling honeycomb | {6,3,4} | {6,3} | {6} | {4} | {3,4} | 0 | {4,3,6} | |

| Order-4 square tiling honeycomb | {4,4,4} | {4,4} | {4} | {4} | {4,4} | 0 | Self-dual | |

| Order-6 dodecahedral honeycomb | {5,3,6} | {5,3} | {5} | {5} | {3,6} | 0 | {6,3,5} | |

| Order-5 hexagonal tiling honeycomb | {6,3,5} | {6,3} | {6} | {5} | {3,5} | 0 | {5,3,6} | |

| Order-6 hexagonal tiling honeycomb | {6,3,6} | {6,3} | {6} | {6} | {3,6} | 0 | Self-dual |

Noncompact solutions exist as Lorentzian Coxeter groups, and can be visualized with open domains in hyperbolic space (the fundamental tetrahedron having ultra-ideal vertices). All honeycombs with hyperbolic cells or vertex figures and do not have 2 in their Schläfli symbol are noncompact.

| {p,3} \ r | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ... ∞ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

{2,3} |

{2,3,2} |

{2,3,3} | {2,3,4} | {2,3,5} | {2,3,6} | {2,3,7} | {2,3,8} | {2,3,∞} |

{3,3} |

{3,3,2} |

{3,3,3} |

{3,3,4} |

{3,3,5} |

{3,3,6} |

{3,3,7} |

{3,3,8} |

{3,3,∞} |

| {4,3} |

{4,3,2} |

{4,3,3} |

{4,3,4} |

{4,3,5} |

{4,3,6} |

{4,3,7} |

{4,3,8} |

{4,3,∞} |

{5,3} |

{5,3,2} |

{5,3,3} |

{5,3,4} |

{5,3,5} |

{5,3,6} |

{5,3,7} |

{5,3,8} |

{5,3,∞} |

{6,3} |

{6,3,2} |

{6,3,3} |

{6,3,4} |

{6,3,5} |

{6,3,6} |

{6,3,7} |

{6,3,8} |

{6,3,∞} |

{7,3} |

{7,3,2} |  {7,3,3} |

{7,3,4} |

{7,3,5} |

{7,3,6} |

{7,3,7} |

{7,3,8} |

{7,3,∞} |

{8,3} |

{8,3,2} |  {8,3,3} |

{8,3,4} |

{8,3,5} |

{8,3,6} |

{8,3,7} |

{8,3,8} |

{8,3,∞} |

... {∞,3} |

{∞,3,2} |  {∞,3,3} |

{∞,3,4} |

{∞,3,5} |

{∞,3,6} |

{∞,3,7} |

{∞,3,8} |

{∞,3,∞} |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are no regular hyperbolic star-honeycombs in H3: all forms with a regular star polyhedron as cell, vertex figure or both end up being spherical.

Ideal vertices now appear when the vertex figure is a Euclidean tiling, becoming inscribable in a horosphere rather than a sphere. They are dual to ideal cells (Euclidean tilings rather than finite polyhedra). As the last number in the Schläfli symbol rises further, the vertex figure becomes hyperbolic, and vertices become ultra-ideal (so the edges do not meet within hyperbolic space). In honeycombs {p, q, ∞} the edges intersect the Poincaré ball only in one ideal point; the rest of the edge has become ultra-ideal. Continuing further would lead to edges that are completely ultra-ideal, both for the honeycomb and for the fundamental simplex (though still infinitely many {p, q} would meet at such edges). In general, when the last number of the Schläfli symbol becomes ∞, faces of codimension two intersect the Poincaré hyperball only in one ideal point.[13]

Four dimensions (5-apeirotopes)

Tessellations of Euclidean 4-space

There are three kinds of infinite regular tessellations (honeycombs) that can tessellate Euclidean four-dimensional space:

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p,q,r,s} |

Facet type {p,q,r} |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Face figure {s} |

Edge figure {r,s} |

Vertex figure {q,r,s} |

Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tesseractic honeycomb | {4,3,3,4} | {4,3,3} | {4,3} | {4} | {4} | {3,4} | {3,3,4} | Self-dual |

| 16-cell honeycomb | {3,3,4,3} | {3,3,4} | {3,3} | {3} | {3} | {4,3} | {3,4,3} | {3,4,3,3} |

| 24-cell honeycomb | {3,4,3,3} | {3,4,3} | {3,4} | {3} | {3} | {3,3} | {4,3,3} | {3,3,4,3} |

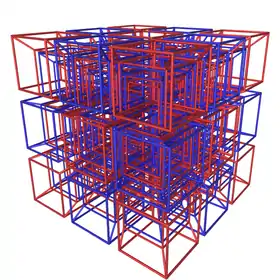

Projected portion of {4,3,3,4} (Tesseractic honeycomb) |

Projected portion of {3,3,4,3} (16-cell honeycomb) |

Projected portion of {3,4,3,3} (24-cell honeycomb) |

There are also the two improper cases {4,3,4,2} and {2,4,3,4}.

There are three flat regular honeycombs of Euclidean 4-space:[21]

- {4,3,3,4}, {3,3,4,3}, and {3,4,3,3}.

There are seven flat regular convex honeycombs of hyperbolic 4-space:[22]

- 5 are compact: {3,3,3,5}, {5,3,3,3}, {4,3,3,5}, {5,3,3,4}, {5,3,3,5}

- 2 are paracompact: {3,4,3,4}, and {4,3,4,3}.

There are four flat regular star honeycombs of hyperbolic 4-space:[22]

- {5/2,5,3,3}, {3,3,5,5/2}, {3,5,5/2,5}, and {5,5/2,5,3}.

Tessellations of hyperbolic 4-space

There are seven convex regular honeycombs and four star-honeycombs in H4 space.[23] Five convex ones are compact, and two are paracompact.

Five compact regular honeycombs in H4:

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p,q,r,s} |

Facet type {p,q,r} |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Face figure {s} |

Edge figure {r,s} |

Vertex figure {q,r,s} |

Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order-5 5-cell honeycomb | {3,3,3,5} | {3,3,3} | {3,3} | {3} | {5} | {3,5} | {3,3,5} | {5,3,3,3} |

| 120-cell honeycomb | {5,3,3,3} | {5,3,3} | {5,3} | {5} | {3} | {3,3} | {3,3,3} | {3,3,3,5} |

| Order-5 tesseractic honeycomb | {4,3,3,5} | {4,3,3} | {4,3} | {4} | {5} | {3,5} | {3,3,5} | {5,3,3,4} |

| Order-4 120-cell honeycomb | {5,3,3,4} | {5,3,3} | {5,3} | {5} | {4} | {3,4} | {3,3,4} | {4,3,3,5} |

| Order-5 120-cell honeycomb | {5,3,3,5} | {5,3,3} | {5,3} | {5} | {5} | {3,5} | {3,3,5} | Self-dual |

The two paracompact regular H4 honeycombs are: {3,4,3,4}, {4,3,4,3}.

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p,q,r,s} |

Facet type {p,q,r} |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Face figure {s} |

Edge figure {r,s} |

Vertex figure {q,r,s} |

Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order-4 24-cell honeycomb | {3,4,3,4} | {3,4,3} | {3,4} | {3} | {4} | {3,4} | {4,3,4} | {4,3,4,3} |

| Cubic honeycomb honeycomb | {4,3,4,3} | {4,3,4} | {4,3} | {4} | {3} | {4,3} | {3,4,3} | {3,4,3,4} |

Noncompact solutions exist as Lorentzian Coxeter groups, and can be visualized with open domains in hyperbolic space (the fundamental 5-cell having some parts inaccessible beyond infinity). All honeycombs which are not shown in the set of tables below and do not have 2 in their Schläfli symbol are noncompact.

| Spherical/Euclidean/hyperbolic(compact/paracompact/noncompact) honeycombs {p,q,r,s} | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Star tessellations of hyperbolic 4-space

There are four regular star-honeycombs in H4 space, all compact:

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p,q,r,s} |

Facet type {p,q,r} |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Face figure {s} |

Edge figure {r,s} |

Vertex figure {q,r,s} |

Dual | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small stellated 120-cell honeycomb | {5/2,5,3,3} | {5/2,5,3} | {5/2,5} | {5/2} | {3} | {3,3} | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5,5/2} | 5 |

| Pentagrammic-order 600-cell honeycomb | {3,3,5,5/2} | {3,3,5} | {3,3} | {3} | {5/2} | {5,5/2} | {3,5,5/2} | {5/2,5,3,3} | 5 |

| Order-5 icosahedral 120-cell honeycomb | {3,5,5/2,5} | {3,5,5/2} | {3,5} | {3} | {5} | {5/2,5} | {5,5/2,5} | {5,5/2,5,3} | 10 |

| Great 120-cell honeycomb | {5,5/2,5,3} | {5,5/2,5} | {5,5/2} | {5} | {3} | {5,3} | {5/2,5,3} | {3,5,5/2,5} | 10 |

Five dimensions (6-apeirotopes)

There is only one flat regular honeycomb of Euclidean 5-space: (previously listed above as tessellations)[21]

- {4,3,3,3,4}

There are five flat regular regular honeycombs of hyperbolic 5-space, all paracompact: (previously listed above as tessellations)[22]

- {3,3,3,4,3}, {3,4,3,3,3}, {3,3,4,3,3}, {3,4,3,3,4}, and {4,3,3,4,3}

Tessellations of Euclidean 5-space

The hypercubic honeycomb is the only family of regular honeycombs that can tessellate each dimension, five or higher, formed by hypercube facets, four around every ridge.

| Name | Schläfli {p1, p2, ..., pn−1} |

Facet type |

Vertex figure |

Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square tiling | {4,4} | {4} | {4} | Self-dual |

| Cubic honeycomb | {4,3,4} | {4,3} | {3,4} | Self-dual |

| Tesseractic honeycomb | {4,32,4} | {4,32} | {32,4} | Self-dual |

| 5-cube honeycomb | {4,33,4} | {4,33} | {33,4} | Self-dual |

| 6-cube honeycomb | {4,34,4} | {4,34} | {34,4} | Self-dual |

| 7-cube honeycomb | {4,35,4} | {4,35} | {35,4} | Self-dual |

| 8-cube honeycomb | {4,36,4} | {4,36} | {36,4} | Self-dual |

| n-hypercubic honeycomb | {4,3n−2,4} | {4,3n−2} | {3n−2,4} | Self-dual |

In E5, there are also the improper cases {4,3,3,4,2}, {2,4,3,3,4}, {3,3,4,3,2}, {2,3,3,4,3}, {3,4,3,3,2}, and {2,3,4,3,3}. In En, {4,3n−3,4,2} and {2,4,3n−3,4} are always improper Euclidean tessellations.

Tessellations of hyperbolic 5-space

There are 5 regular honeycombs in H5, all paracompact, which include infinite (Euclidean) facets or vertex figures: {3,4,3,3,3}, {3,3,4,3,3}, {3,3,3,4,3}, {3,4,3,3,4}, and {4,3,3,4,3}.

There are no compact regular tessellations of hyperbolic space of dimension 5 or higher and no paracompact regular tessellations in hyperbolic space of dimension 6 or higher.

| Name | Schläfli Symbol {p,q,r,s,t} |

Facet type {p,q,r,s} |

4-face type {p,q,r} |

Cell type {p,q} |

Face type {p} |

Cell figure {t} |

Face figure {s,t} |

Edge figure {r,s,t} |

Vertex figure {q,r,s,t} |

Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-orthoplex honeycomb | {3,3,3,4,3} | {3,3,3,4} | {3,3,3} | {3,3} | {3} | {3} | {4,3} | {3,4,3} | {3,3,4,3} | {3,4,3,3,3} |

| 24-cell honeycomb honeycomb | {3,4,3,3,3} | {3,4,3,3} | {3,4,3} | {3,4} | {3} | {3} | {3,3} | {3,3,3} | {4,3,3,3} | {3,3,3,4,3} |

| 16-cell honeycomb honeycomb | {3,3,4,3,3} | {3,3,4,3} | {3,3,4} | {3,3} | {3} | {3} | {3,3} | {4,3,3} | {3,4,3,3} | self-dual |

| Order-4 24-cell honeycomb honeycomb | {3,4,3,3,4} | {3,4,3,3} | {3,4,3} | {3,4} | {3} | {4} | {3,4} | {3,3,4} | {4,3,3,4} | {4,3,3,4,3} |

| Tesseractic honeycomb honeycomb | {4,3,3,4,3} | {4,3,3,4} | {4,3,3} | {4,3} | {4} | {3} | {4,3} | {3,4,3} | {3,3,4,3} | {3,4,3,3,4} |

Since there are no regular star n-polytopes for n ≥ 5, that could be potential cells or vertex figures, there are no more hyperbolic star honeycombs in Hn for n ≥ 5.

6 dimensions and higher (7-apeirotopes+)

Tessellations of hyperbolic 6-space and higher

There are no regular compact or paracompact tessellations of hyperbolic space of dimension 6 or higher. However, any Schläfli symbol of the form {p,q,r,s,...} not covered above (p,q,r,s,... natural numbers above 2, or infinity) will form a noncompact tessellation of hyperbolic n-space.[13]

Compound polytopes

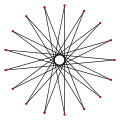

Two dimensional compounds

For any natural number n, there are n-pointed star regular polygonal stars with Schläfli symbols {n/m} for all m such that m < n/2 (strictly speaking {n/m}={n/(n−m)}) and m and n are coprime. When m and n are not coprime, the star polygon obtained will be a regular polygon with n/m sides. A new figure is obtained by rotating these regular n/m-gons one vertex to the left on the original polygon until the number of vertices rotated equals n/m minus one, and combining these figures. An extreme case of this is where n/m is 2, producing a figure consisting of n/2 straight line segments; this is called a degenerate star polygon.

In other cases where n and m have a common factor, a star polygon for a lower n is obtained, and rotated versions can be combined. These figures are called star figures, improper star polygons or compound polygons. The same notation {n/m} is often used for them, although authorities such as Grünbaum (1994) regard (with some justification) the form k{n} as being more correct, where usually k = m.

A further complication comes when we compound two or more star polygons, as for example two pentagrams, differing by a rotation of 36°, inscribed in a decagon. This is correctly written in the form k{n/m}, as 2{5/2}, rather than the commonly used {10/4}.

Coxeter's extended notation for compounds is of the form c{m,n,...}[d{p,q,...}]e{s,t,...}, indicating that d distinct {p,q,...}'s together cover the vertices of {m,n,...} c times and the facets of {s,t,...} e times. If no regular {m,n,...} exists, the first part of the notation is removed, leaving [d{p,q,...}]e{s,t,...}; the opposite holds if no regular {s,t,...} exists. The dual of c{m,n,...}[d{p,q,...}]e{s,t,...} is e{t,s,...}[d{q,p,...}]c{n,m,...}. If c or e are 1, they may be omitted. For compound polygons, this notation reduces to {nk}[k{n/m}]{nk}: for example, the hexagram may be written thus as {6}[2{3}]{6}.

.svg.png.webp) 2{2} |

3{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{2} |

5{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 6{2} |

7{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 8{2} |

9{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 10{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 11{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 12{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 13{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 14{2} |

.svg.png.webp) 15{2} | |

2{3} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{3} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{3} |

.svg.png.webp) 5{3} |

6{3} |

.svg.png.webp) 7{3} |

.svg.png.webp) 8{3} |

.svg.png.webp) 9{3} |

.svg.png.webp) 10{3} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{4} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{4} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{4} |

.svg.png.webp) 5{4} |

.svg.png.webp) 6{4} |

.svg.png.webp) 7{4} |

2{5} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{5} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{5} |

.svg.png.webp) 5{5} |

.svg.png.webp) 6{5} |

2{5/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{5/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{5/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 5{5/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 6{5/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{6} |

3{6} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{6} |

.svg.png.webp) 5{6} | |

2{7} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{7} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{7} |

2{7/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{7/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{7/2} |

2{7/3} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{7/3} |

.svg.png.webp) 4{7/3} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{8} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{8} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{8/3} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{8/3} | ||

2{9} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{9} |

2{9/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{9/2} |

2{9/4} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{9/4} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{10} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{10} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{10/3} |

.svg.png.webp) 3{10/3} | |||||

.svg.png.webp) 2{11} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{11/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{11/3} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{11/4} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{11/5} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{12} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{12/5} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{13} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{13/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{13/3} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{13/4} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{13/5} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{13/6} | ||

.svg.png.webp) 2{14} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{14/3} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{14/5} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{15} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{15/2} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{15/4} |

.svg.png.webp) 2{15/7} |

Regular skew polygons also create compounds, seen in the edges of prismatic compound of antiprisms, for instance:

| Compound skew squares |

Compound skew hexagons |

Compound skew decagons | |

| Two {2}#{ } | Three {2}#{ } | Two {3}#{ } | Two {5/3}#{ } |

|

|

|

|

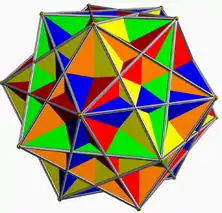

Three dimensional compounds

A regular polyhedron compound can be defined as a compound which, like a regular polyhedron, is vertex-transitive, edge-transitive, and face-transitive. With this definition there are 5 regular compounds.

| Symmetry | [4,3], Oh | [5,3]+, I | [5,3], Ih | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duality | Self-dual | Dual pairs | |||

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

| Spherical |  |

|

|

|

|

| Polyhedra | 2 {3,3} | 5 {3,3} | 10 {3,3} | 5 {4,3} | 5 {3,4} |

| Coxeter | {4,3}[2{3,3}]{3,4} | {5,3}[5{3,3}]{3,5} | 2{5,3}[10{3,3}]2{3,5} | 2{5,3}[5{4,3}] | [5{3,4}]2{3,5} |

Coxeter's notation for regular compounds is given in the table above, incorporating Schläfli symbols. The material inside the square brackets, [d{p,q}], denotes the components of the compound: d separate {p,q}'s. The material before the square brackets denotes the vertex arrangement of the compound: c{m,n}[d{p,q}] is a compound of d {p,q}'s sharing the vertices of an {m,n} counted c times. The material after the square brackets denotes the facet arrangement of the compound: [d{p,q}]e{s,t} is a compound of d {p,q}'s sharing the faces of {s,t} counted e times. These may be combined: thus c{m,n}[d{p,q}]e{s,t} is a compound of d {p,q}'s sharing the vertices of {m,n} counted c times and the faces of {s,t} counted e times. This notation can be generalised to compounds in any number of dimensions.[24]

Euclidean and hyperbolic plane compounds

There are eighteen two-parameter families of regular compound tessellations of the Euclidean plane. In the hyperbolic plane, five one-parameter families and seventeen isolated cases are known, but the completeness of this listing has not yet been proven.

The Euclidean and hyperbolic compound families 2 {p,p} (4 ≤ p ≤ ∞, p an integer) are analogous to the spherical stella octangula, 2 {3,3}.

| Self-dual | Duals | Self-dual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 {4,4} | 2 {6,3} | 2 {3,6} | 2 {∞,∞} |

|

|

|

|

| {{4,4}} or a{4,4} or {4,4}[2{4,4}]{4,4} |

[2{6,3}]{3,6} | a{6,3} or {6,3}[2{3,6}] |

{{∞,∞}} or a{∞,∞} or {4,∞}[2{∞,∞}]{∞,4} |

| 3 {6,3} | 3 {3,6} | 3 {∞,∞} | |

|

|

| |

| 2{3,6}[3{6,3}]{6,3} | {3,6}[3{3,6}]2{6,3} |

||

Four dimensional compounds

|

|

| 75 {4,3,3} | 75 {3,3,4} |

|---|

Coxeter lists 32 regular compounds of regular 4-polytopes in his book Regular Polytopes.[25] McMullen adds six in his paper New Regular Compounds of 4-Polytopes, in which he also proves that the list is now complete.[26] In the following tables, the superscript (var) indicates that the labeled compounds are distinct from the other compounds with the same symbols.

| Compound | Constituent | Symmetry | Vertex arrangement | Cell arrangement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 {3,3,3} | 5-cell | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 120 {3,3,3}(var) | 5-cell | order 1200[26] | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 720 {3,3,3} | 5-cell | [5,3,3], order 14400[26] | 6{5,3,3} | 6{3,3,5} |

| 5 {3,4,3} | 24-cell | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | {3,3,5} | {5,3,3} |

| Compound 1 | Compound 2 | Symmetry | Vertex arrangement (1) | Cell arrangement (1) | Vertex arrangement (2) | Cell arrangement (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 {3,3,4}[27] | 3 {4,3,3} | [3,4,3], order 1152[25] | {3,4,3} | 2{3,4,3} | 2{3,4,3} | {3,4,3} |

| 15 {3,3,4} | 15 {4,3,3} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | {3,3,5} | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} | {5,3,3} |

| 75 {3,3,4} | 75 {4,3,3} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | 5{3,3,5} | 10{5,3,3} | 10{3,3,5} | 5{5,3,3} |

| 75 {3,3,4} | 75 {4,3,3} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | {5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} | 2{5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 75 {3,3,4} | 75 {4,3,3} | order 600[26] | {5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} | 2{5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 300 {3,3,4} | 300 {4,3,3} | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] | 4{5,3,3} | 8{3,3,5} | 8{5,3,3} | 4{3,3,5} |

| 600 {3,3,4} | 600 {4,3,3} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | 8{5,3,3} | 16{3,3,5} | 16{5,3,3} | 8{3,3,5} |

| 25 {3,4,3} | 25 {3,4,3} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | {5,3,3} | 5{5,3,3} | 5{3,3,5} | {3,3,5} |

There are two different compounds of 75 tesseracts: one shares the vertices of a 120-cell, while the other shares the vertices of a 600-cell. It immediately follows therefore that the corresponding dual compounds of 75 16-cells are also different.

| Compound | Symmetry | Vertex arrangement | Cell arrangement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 {5,5/2,5} | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 10 {5,5/2,5} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} |

| 5 {5/2,5,5/2} | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 10 {5/2,5,5/2} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} |

| Compound 1 | Compound 2 | Symmetry | Vertex arrangement (1) | Cell arrangement (1) | Vertex arrangement (2) | Cell arrangement (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 {3,5,5/2} | 5 {5/2,5,3} | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 10 {3,5,5/2} | 10 {5/2,5,3} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} |

| 5 {5,5/2,3} | 5 {3,5/2,5} | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 10 {5,5/2,3} | 10 {3,5/2,5} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} |

| 5 {5/2,3,5} | 5 {5,3,5/2} | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} | {5,3,3} | {3,3,5} |

| 10 {5/2,3,5} | 10 {5,3,5/2} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} | 2{5,3,3} | 2{3,3,5} |

There are also fourteen partially regular compounds, that are either vertex-transitive or cell-transitive but not both. The seven vertex-transitive partially regular compounds are the duals of the seven cell-transitive partially regular compounds.

| Compound 1 Vertex-transitive |

Compound 2 Cell-transitive |

Symmetry |

|---|---|---|

| 2 16-cells[28] | 2 tesseracts | [4,3,3], order 384[25] |

| 25 24-cell(var) | 25 24-cell(var) | order 600[26] |

| 100 24-cell | 100 24-cell | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] |

| 200 24-cell | 200 24-cell | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] |

| 5 600-cell | 5 120-cell | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] |

| 10 600-cell | 10 120-cell | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] |

| Compound 1 Vertex-transitive |

Compound 2 Cell-transitive |

Symmetry |

|---|---|---|

| 5 {3,3,5/2} | 5 {5/2,3,3} | [5,3,3]+, order 7200[25] |

| 10 {3,3,5/2} | 10 {5/2,3,3} | [5,3,3], order 14400[25] |

Although the 5-cell and 24-cell are both self-dual, their dual compounds (the compound of two 5-cells and compound of two 24-cells) are not considered to be regular, unlike the compound of two tetrahedra and the various dual polygon compounds, because they are neither vertex-regular nor cell-regular: they are not facetings or stellations of any regular 4-polytope. However, they are vertex-, edge-, face-, and cell-transitive.

Euclidean 3-space compounds

The only regular Euclidean compound honeycombs are an infinite family of compounds of cubic honeycombs, all sharing vertices and faces with another cubic honeycomb. This compound can have any number of cubic honeycombs. The Coxeter notation is {4,3,4}[d{4,3,4}]{4,3,4}.

Five dimensions and higher compounds

There are no regular compounds in five or six dimensions. There are three known seven-dimensional compounds (16, 240, or 480 7-simplices), and six known eight-dimensional ones (16, 240, or 480 8-cubes or 8-orthoplexes). There is also one compound of n-simplices in n-dimensional space provided that n is one less than a power of two, and also two compounds (one of n-cubes and a dual one of n-orthoplexes) in n-dimensional space if n is a power of two.

The Coxeter notation for these compounds are (using αn = {3n−1}, βn = {3n−2,4}, γn = {4,3n−2}):

- 7-simplexes: cγ7[16cα7]cβ7, where c = 1, 15, or 30

- 8-orthoplexes: cγ8[16cβ8]

- 8-cubes: [16cγ8]cβ8

The general cases (where n = 2k and d = 22k − k − 1, k = 2, 3, 4, ...):

- Simplexes: γn−1[dαn−1]βn−1

- Orthoplexes: γn[dβn]

- Hypercubes: [dγn]βn

Euclidean honeycomb compounds

A known family of regular Euclidean compound honeycombs in five or more dimensions is an infinite family of compounds of hypercubic honeycombs, all sharing vertices and faces with another hypercubic honeycomb. This compound can have any number of hypercubic honeycombs. The Coxeter notation is δn[dδn]δn where δn = {∞} when n = 2 and {4,3n−3,4} when n ≥ 3.

Abstract polytopes

The abstract polytopes arose out of an attempt to study polytopes apart from the geometrical space they are embedded in. They include the tessellations of spherical, Euclidean and hyperbolic space, tessellations of other manifolds, and many other objects that do not have a well-defined topology, but instead may be characterised by their "local" topology. There are infinitely many in every dimension. See this atlas for a sample. Some notable examples of abstract regular polytopes that do not appear elsewhere in this list are the 11-cell, {3,5,3}, and the 57-cell, {5,3,5}, which have regular projective polyhedra as cells and vertex figures.

The elements of an abstract polyhedron are its body (the maximal element), its faces, edges, vertices and the null polytope or empty set. These abstract elements can be mapped into ordinary space or realised as geometrical figures. Some abstract polyhedra have well-formed or faithful realisations, others do not. A flag is a connected set of elements of each dimension - for a polyhedron that is the body, a face, an edge of the face, a vertex of the edge, and the null polytope. An abstract polytope is said to be regular if its combinatorial symmetries are transitive on its flags - that is to say, that any flag can be mapped onto any other under a symmetry of the polyhedron. Abstract regular polytopes remain an active area of research.

Five such regular abstract polyhedra, which can not be realised faithfully, were identified by H. S. M. Coxeter in his book Regular Polytopes (1977) and again by J. M. Wills in his paper "The combinatorially regular polyhedra of index 2" (1987).[29] They are all topologically equivalent to toroids. Their construction, by arranging n faces around each vertex, can be repeated indefinitely as tilings of the hyperbolic plane. In the diagrams below, the hyperbolic tiling images have colors corresponding to those of the polyhedra images.

Polyhedron

Medial rhombic triacontahedron

Dodecadodecahedron

Medial triambic icosahedron

Ditrigonal dodecadodecahedron

Excavated dodecahedronVertex figure {5}, {5/2}

(5.5/2)2

{5}, {5/2}

(5.5/3)3

Faces 30 rhombi

12 pentagons

12 pentagrams

20 hexagons

12 pentagons

12 pentagrams

20 hexagrams

Tiling

{4, 5}

{5, 4}

{6, 5}

{5, 6}

{6, 6}χ −6 −6 −16 −16 −20

These occur as dual pairs as follows:

- The medial rhombic triacontahedron and dodecadodecahedron are dual to each other.

- The medial triambic icosahedron and ditrigonal dodecadodecahedron are dual to each other.

- The excavated dodecahedron is self-dual.

See also

- Polygon

- Polyhedron

- Regular polyhedron (5 regular Platonic solids and 4 Kepler–Poinsot solids)

- Petrial

- 4-polytope

- Regular 4-polytope (16 regular 4-polytopes, 4 convex and 10 star (Schläfli–Hess))

- Uniform 4-polytope

- Tessellation

- Regular polytope

- Regular map (graph theory)

Notes

- ↑ Coxeter (1973), p. 129.

- ↑ McMullen & Schulte (2002), p. 30.

- ↑ Johnson, N.W. (2018). "Chapter 11: Finite symmetry groups". Geometries and Transformations. 11.1 Polytopes and Honeycombs, p. 224. ISBN 978-1-107-10340-5.

- ↑ Coxeter (1973), p. 120.

- ↑ Coxeter (1973), p. 124.

- ↑ Coxeter, Regular Complex Polytopes, p. 9

- ↑ Duncan, Hugh (28 September 2017). "Between a square rock and a hard pentagon: Fractional polygons". chalkdust.

- ↑ Coxeter (1973), pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Abstracts (PDF). Convex and Abstract Polytopes (May 19–21, 2005) and Polytopes Day in Calgary (May 22, 2005).

- ↑ Coxeter (1973), Table I: Regular polytopes, (iii) The three regular polytopes in n dimensions (n>=5), pp. 294–295.

- ↑ McMullen & Schulte (2002), "6C Projective Regular Polytopes" pp. 162-165.

- ↑ Grünbaum, B. (1977). "Regular Polyhedra—Old and New". Aequationes Mathematicae. 16 (1–2): 1–20. doi:10.1007/BF01836414. S2CID 125049930.

- 1 2 3 Roice Nelson and Henry Segerman, Visualizing Hyperbolic Honeycombs

- ↑ Irving Adler, A New Look at Geometry (2012 Dover edition), p.233

- ↑ Coxeter, H.S.M. (1938). "Regular Skew Polyhedra in Three and Four Dimensions". Proc. London Math. Soc. 2. 43: 33–62. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-43.1.33.

- ↑ Coxeter, H.S.M. (1985). "Regular and semi-regular polytopes II". Mathematische Zeitschrift. 188 (4): 559–591. doi:10.1007/BF01161657. S2CID 120429557.

- ↑ Conway, John H.; Burgiel, Heidi; Goodman-Strauss, Chaim (2008). "Chapter 23: Objects with Primary Symmetry, Infinite Platonic Polyhedra". The Symmetries of Things. Taylor & Francis. pp. 333–335. ISBN 978-1-568-81220-5.

- ↑ McMullen & Schulte (2002), p. 224.

- ↑ McMullen & Schulte (2002), Section 7E.

- ↑ Garner, C.W.L. (1967). "Regular Skew Polyhedra in Hyperbolic Three-Space". Can. J. Math. 19: 1179–1186. doi:10.4153/CJM-1967-106-9. S2CID 124086497. Note: His paper says there are 32, but one is self-dual, leaving 31.

- 1 2 3 Coxeter (1973), Table II: Regular honeycombs, p. 296.

- 1 2 3 4 Coxeter (1999), "Chapter 10".

- ↑ Coxeter (1999), "Chapter 10" Table IV, p. 213.

- ↑ Coxeter (1973), p. 48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Coxeter (1973). Table VII, p. 305

- 1 2 3 4 5 McMullen (2018).

- ↑ Klitzing, Richard. "Uniform compound stellated icositetrachoron".

- ↑ Klitzing, Richard. "Uniform compound demidistesseract".

- ↑ David A. Richter. "The Regular Polyhedra (of index two)".

References

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1999), "Chapter 10: Regular Honeycombs in Hyperbolic Space", The Beauty of Geometry: Twelve Essays, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 199–214, ISBN 0-486-40919-8, LCCN 99035678, MR 1717154. See in particular Summary Tables II, III, IV, V, pp. 212–213.

- Originally published in Coxeter, H. S. M. (1956), "Regular honeycombs in hyperbolic space" (PDF), Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians, 1954, Amsterdam, vol. III, Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co., pp. 155–169, MR 0087114, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02.

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1973) [1948]. Regular Polytopes (Third ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-61480-8. MR 0370327. OCLC 798003. See in particular Tables I and II: Regular polytopes and honeycombs, pp. 294–296.

- Johnson, Norman W. (2012), "Regular inversive polytopes" (PDF), International Conference on Mathematics of Distances and Applications (July 2–5, 2012, Varna, Bulgaria), pp. 85–95 Paper 27

- McMullen, Peter; Schulte, Egon (2002), Abstract Regular Polytopes, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, vol. 92, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511546686, ISBN 0-521-81496-0, MR 1965665, S2CID 115688843

- McMullen, Peter (2018), "New Regular Compounds of 4-Polytopes", New Trends in Intuitive Geometry, Bolyai Society Mathematical Studies, 27: 307–320, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-57413-3_12, ISBN 978-3-662-57412-6.

- Nelson, Roice; Segerman, Henry (2015). "Visualizing Hyperbolic Honeycombs". arXiv:1511.02851 [math.HO]. hyperbolichoneycombs.org/

- Sommerville, D. M. Y. (1958), An Introduction to the Geometry of n Dimensions, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., MR 0100239. Reprint of 1930 ed., published by E. P. Dutton. See in particular Chapter X: The Regular Polytopes.

External links

- The Platonic Solids

- Kepler-Poinsot Polyhedra

- Regular 4d Polytope Foldouts

- Multidimensional Glossary (Look up Hexacosichoron and Hecatonicosachoron)

- Polytope Viewer

- Polytopes and optimal packing of p points in n dimensional spheres

- An atlas of small regular polytopes

- Regular polyhedra through time I. Hubard, Polytopes, Maps and their Symmetries

- Regular Star Polytopes, Nan Ma

| Space | Family | / / | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 | Uniform tiling | {3[3]} | δ3 | hδ3 | qδ3 | Hexagonal |

| E3 | Uniform convex honeycomb | {3[4]} | δ4 | hδ4 | qδ4 | |

| E4 | Uniform 4-honeycomb | {3[5]} | δ5 | hδ5 | qδ5 | 24-cell honeycomb |

| E5 | Uniform 5-honeycomb | {3[6]} | δ6 | hδ6 | qδ6 | |

| E6 | Uniform 6-honeycomb | {3[7]} | δ7 | hδ7 | qδ7 | 222 |

| E7 | Uniform 7-honeycomb | {3[8]} | δ8 | hδ8 | qδ8 | 133 • 331 |

| E8 | Uniform 8-honeycomb | {3[9]} | δ9 | hδ9 | qδ9 | 152 • 251 • 521 |

| E9 | Uniform 9-honeycomb | {3[10]} | δ10 | hδ10 | qδ10 | |

| E10 | Uniform 10-honeycomb | {3[11]} | δ11 | hδ11 | qδ11 | |

| En-1 | Uniform (n-1)-honeycomb | {3[n]} | δn | hδn | qδn | 1k2 • 2k1 • k21 |