In geometry, a skew polygon is a polygon whose vertices are not all coplanar.[1] Skew polygons must have at least four vertices. The interior surface (or area) of such a polygon is not uniquely defined.

Skew infinite polygons (apeirogons) have vertices which are not all colinear.

A zig-zag skew polygon or antiprismatic polygon[2] has vertices which alternate on two parallel planes, and thus must be even-sided.

Regular skew polygons in 3 dimensions (and regular skew apeirogons in two dimensions) are always zig-zag.

Antiprismatic skew polygon in three dimensions

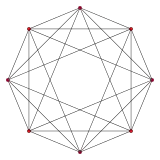

A regular skew polygon is isogonal with equal edge lengths. In 3 dimensions a regular skew polygon is a zig-zag skew (or antiprismatic) polygon, with vertices alternating between two parallel planes. The side edges of an n-antiprism can define a regular skew 2n-gon.

A regular skew n-gon can be given a Schläfli symbol {p}#{ } as a blend of a regular polygon {p} and an orthogonal line segment { }.[3] The symmetry operation between sequential vertices is glide reflection.

Examples are shown on the uniform square and pentagon antiprisms. The star antiprisms also generate regular skew polygons with different connection order of the top and bottom polygons. The filled top and bottom polygons are drawn for structural clarity, and are not part of the skew polygons.

| Skew square | Skew hexagon | Skew octagon | Skew decagon | Skew dodecagon | ||

| {2}#{ } | {3}#{ } | {4}#{ } | {5}#{ } | {5/2}#{ } | {5/3}#{ } | {6}#{ } |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| s{2,4} | s{2,6} | s{2,8} | s{2,10} | sr{2,5/2} | s{2,10/3} | s{2,12} |

A regular compound skew 2n-gon can be similarly constructed by adding a second skew polygon by a rotation. These share the same vertices as the prismatic compound of antiprisms.

| Skew squares | Skew hexagons | Skew decagons | |

| Two {2}#{ } | Three {2}#{ } | Two {3}#{ } | Two {5/3}#{ } |

|

|

|

|

Petrie polygons are regular skew polygons defined within regular polyhedra and polytopes. For example, the five Platonic solids have 4-, 6-, and 10-sided regular skew polygons, as seen in these orthogonal projections with red edges around their respective projective envelopes. The tetrahedron and the octahedron include all the vertices in their respective zig-zag skew polygons, and can be seen as a digonal antiprism and a triangular antiprism respectively.

Regular skew polygon as vertex figure of regular skew polyhedron

A regular skew polyhedron has regular polygon faces, and a regular skew polygon vertex figure.

Three infinite regular skew polyhedra are space-filling in 3-space; others exist in 4-space, some within the uniform 4-polytopes.

| {4,6|4} | {6,4|4} | {6,6|3} |

|---|---|---|

Regular skew hexagon {3}#{ } |

Regular skew square {2}#{ } |

Regular skew hexagon {3}#{ } |

Regular skew polygons in four dimensions

In 4 dimensions, a regular skew polygon can have vertices on a Clifford torus and related by a Clifford displacement. Unlike zig-zag skew polygons, skew polygons on double rotations can include an odd-number of sides.

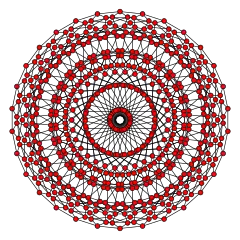

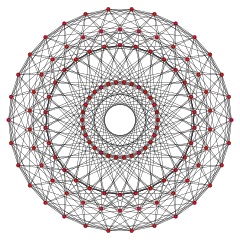

The Petrie polygons of the regular 4-polytopes define regular zig-zag skew polygons. The Coxeter number for each coxeter group symmetry expresses how many sides a Petrie polygon has. This is 5 sides for a 5-cell, 8 sides for a tesseract and 16-cell, 12 sides for a 24-cell, and 30 sides for a 120-cell and 600-cell.

When orthogonally projected onto the Coxeter plane, these regular skew polygons appear as regular polygon envelopes in the plane.

| A4, [3,3,3] | B4, [4,3,3] | F4, [3,4,3] | H4, [5,3,3] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentagon | Octagon | Dodecagon | Triacontagon | ||

5-cell {3,3,3} |

tesseract {4,3,3} |

16-cell {3,3,4} |

24-cell {3,4,3} |

120-cell {5,3,3} |

600-cell {3,3,5} |

The n-n duoprisms and dual duopyramids also have 2n-gonal Petrie polygons. (The tesseract is a 4-4 duoprism, and the 16-cell is a 4-4 duopyramid.)

| Hexagon | Decagon | Dodecagon | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

3-3 duoprism |

3-3 duopyramid |

5-5 duoprism |

5-5 duopyramid |

6-6 duoprism |

6-6 duopyramid |

See also

- Petrie polygon

- Quadrilateral#Skew quadrilaterals

- Regular skew polyhedron

- Skew apeirohedron (infinite skew polyhedron)

- Skew lines

Citations

- ↑ Coxeter 1973, §1.1 Regular polygons; "If the vertices are all coplanar, we speak of a plane polygon, otherwise a skew polygon."

- ↑ Regular complex polytopes, p. 6

- ↑ Abstract Regular Polytopes, p.217

References

- McMullen, Peter; Schulte, Egon (December 2002), Abstract Regular Polytopes (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-81496-0 p. 25

- Williams, Robert (1979). The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-23729-X. "Skew Polygons (Saddle Polygons)" §2.2

- Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973) [1948]. Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). New York: Dover.

- Coxeter, H.S.M.; Regular complex polytopes (1974). Chapter 1. Regular polygons, 1.5. Regular polygons in n dimensions, 1.7. Zigzag and antiprismatic polygons, 1.8. Helical polygons. 4.3. Flags and Orthoschemes, 11.3. Petrie polygons

- Coxeter, H. S. M. Petrie Polygons. Regular Polytopes, 3rd ed. New York: Dover, 1973. (sec 2.6 Petrie Polygons pp. 24–25, and Chapter 12, pp. 213–235, The generalized Petrie polygon)

- Coxeter, H. S. M. & Moser, W. O. J. (1980). Generators and Relations for Discrete Groups. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-09212-9. (1st ed, 1957) 5.2 The Petrie polygon {p,q}.

- John Milnor: On the total curvature of knots, Ann. Math. 52 (1950) 248–257.

- J.M. Sullivan: Curves of finite total curvature, ArXiv:math.0606007v2