| Nabû-mukin-zēri | |

|---|---|

| King of Babylon | |

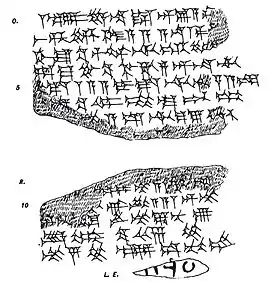

Text dated to Nabû-mukin-zēri's 4th year[i 1] | |

| Reign | 731–729 BC |

| Predecessor | Nabû-šuma-ukîn II |

| Successor | Tukultī-apil-Ešarra III |

| House | Dynasty of E |

Nabû-mukin-zēri, inscribed mdAG-DU-NUMUN,[i 1] also known as Mukin-zēri,[i 2] was the king of Babylon 731–729 BC. The Ptolemaic Canon gives his name as Χινζηρος. His reign was brought to its eventual end by the capture of the stronghold of Šapia by the forces of the Assyrian king Tukultī-apil-Ešarra III (745–727 BC). The chief of the Chaldean Amukanu tribe in southern Babylonia, he took advantage of the instability which attended the revolt against Nabû-nādin-zēri and deposed its leader, Nabû-šuma-ukîn II.

History

The fortuitous discovery in 1952 of a cache of diplomatic correspondence in the chancery offices of the Northwest Palace in a room designated as ZT 4 at Kalhu, modern Nimrud, by archaeologists led by Max Mallowan, has shed much light on events of the Mukin-zēri rebellion. Of the more than three hundred tablets uncovered, a group of more than twenty letters and fragments concerned the events in Babylonia which led to Assyrian intervention and subsequent annexation of the region around 730 BC. They paint a picture of Babylonia riven by splits and rivalries among the various Aramaic, Babylonian and Chaldean factions.

Soon after the Amukanite removed his predecessor from the throne and seized it for himself,[i 3] Tukultī-apil-Ešarra directed his efforts to the removal of the usurper using all available means at his disposal. A letter describes the outcome of a mission to Babylon to win over the support of the city's elders.[i 4] The Assyrian delegation of two officers, Šamaš-bunaya and Nabû-namir, was forced to conduct its diplomacy outside the gates of the city, in full view of Nabû-mukin-zēri's representative, Asinu. “Why do you act in a hostile manner towards us for their sake? They belong among the Chaldeans! It is the Assyrian king who can show favors towards Babylon, maintaining your civic privileges!”[1]

Tukultī-apil-Ešarra's invasion of 731 BC caused Nabû-mukin-zēri to flee Babylon for Šapia, his stronghold in the south, where he remained holed up while the Assyrian forces devastated its surroundings and felled its date palms. The Assyrian king exacted tribute from the other Chaldean tribal leaders, Marduk-apla-iddina II of the Bīt-Yakin, called the “King of the Sealand” in the Assyrian account, Balassu of the Bīt-Dakuri and Nadinu of Larak. Others remained more recalcitrant: Zakiru of the Bīt-Ša’alli was ultimately overthrown, his capital Dur-Illayatu demolished and he was hauled off to Assyria in chains, and Nabû-ušabši of the Bīt-Šilani was impaled. Although the cities of Nippur and Dilbat supported the Assyrian side, the latter city was the subject of reprisals by Mukin-zēri's allies from the religious establishment in Babylon.[i 5] The Assyrian cavalry commander Iasubaya reported on his unsuccessful efforts to lure the Arameans from the usurper's side and to compel them to leave their city and join the Assyrians in their campaign. The fear engendered by Mukin-zēri sometimes kept Assyrian sympathizers from giving them active aid or accepting their generous amnesty terms.[2] But, while Mukin-zēri's forces were engaged in battle in Buharu, his own subjects ("Akkadians") apparently rustled his sheep.[3] Mukin-zēri countered the Assyrians’ propaganda by attempting to divide their allies. He warned Marduk-apla-iddina of the vicissitude of his uncle Balassu.[i 6]

The Chronicle on the Reigns from Nabû-Nasir to Šamaš-šuma-ukin describes the final outcome, “In the third year, the Assyrian king having come down to Akkad, ravaged Bīt-Amukanu and captured Nabû-mukin-zeri. He subsequently ascended the throne in Babylon himself.”[i 3] This chronicle is not wholly accurate as a contemporary letter addressed to Tukultī-apil-Ešarra[i 7] has been preserved which reports that "Mukin-zeri has been killed and Šumu-ukin, his son, has also been killed. The city is conquered." Tukultī-apil-Ešarra did, however, ascend the throne of Babylon, officiating over two successive Akītu festivals.[4]

Inscriptions

References

- ↑ Mogens Herman Hansen (2000). A comparative study of thirty city-state cultures: an investigation, Volume 21. Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. p. 125.

- ↑ J. A. Brinkman (1968). A political history of post-Kassite Babylonia, 1158–722 B.C. Analecta Orientalia. p. 238.

- ↑ Peter Dubovský (2006). Hezekiah and the Assyrian spies. Pontifical Biblical Institute. pp. 161–168.

- ↑ J. A. Brinkman (1984). Prelude to Empire: Babylonian Society and Politics, 747-626 B.C. Vol. 7. Philadelphia: Occasional Publications of the Babylonian Fund. pp. 42–43.