| Vologases V 𐭅𐭋𐭂𐭔 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings | |

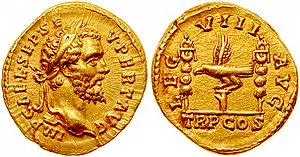

%252C_Hamadan_mint.jpg.webp) Coin of Vologases V, Ecbatana mint | |

| King of Armenia | |

| Reign | 180 – 191 |

| Predecessor | Sohaemus |

| Successor | Khosrov I |

| King of the Parthian Empire | |

| Reign | 191 – 208 |

| Predecessor | Vologases IV |

| Successor | Vologases VI |

| Died | 208 |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Arsacid dynasty |

| Father | Vologases IV |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Vologases V (Parthian: 𐭅𐭋𐭂𐭔 Walagash) was King of Kings of the Parthian Empire from 191 to 208. As king of Armenia (r. 180–191), he is known as Vologases II. Not much is known about his period of kingship of Armenia, except that he put his son Rev I (r. 186–216) on the Iberian throne in 189. Vologases succeeded his father Vologases IV as king of the Parthian Empire in 191; it is uncertain if the transition of power was peaceful or if Vologases took the throne in a civil war. When Vologases acceded the Parthian throne, he passed the Armenian throne to his son Khosrov I (r. 191–217).

Vologases' reign was marked by war with the Roman Empire, lasting from 195 to 202, resulting in the brief capture of the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon, and reaffirmation of Roman rule in Armenia and northern Mesopotamia. At the same time, internal conflict took place in the Parthian realm, with the local Persian prince Pabag seizing Istakhr, the capital of the southern Iranian region of Persis.

Name

Vologases is the Greek and Latin form of the Parthian Walagaš (𐭅𐭋𐭂𐭔). The name is also attested in New Persian as Balāsh and Middle Persian as Wardākhsh (also spelled Walākhsh). The etymology of the name is unclear, although Ferdinand Justi proposes that Walagaš, the first form of the name, is a compound of words "strength" (varəda), and "handsome" (gaš or geš in Modern Persian).[1]

Biography

King of Armenia

During Vologases' early life, he became the ruler of Armenia, succeeding Sohaemus.[2][3][4] Throughout the 1st and 2nd-centuries, the Armenian throne was usually occupied by a close relative of the Parthian King of Kings, who held the title of "Great King of Armenia".[5][lower-alpha 1] Unlike the previous eight Arsacid princes who ruled Armenia, Vologases was able to ensure that his descendants ruled on the Armenian throne; they would rule the country until the Sasanian abolition of the Armenian throne in 428.[2]

In 189, he also imposed his son Rev I (whose mother was the sister of the Pharnavazid ruler Amazasp) on the Iberian throne.[8] His descendants would rule Iberia until 284 when it was replaced by another Parthian family, the Mihranids.[9]

King of the Parthian Empire

In 191 after the death of his father Vologases IV, Vologases ascended the Parthian throne and passed the Armenian throne to his son Khosrov I (r. 191–217).[2][3] It is uncertain if the transition of power was peaceful or marred in a civil war.[1][10] His claim to the throne, however, was not uncontested; a rival king, Osroes II (190), had set himself up in Media even before the death of Vologases IV, but Vologases appears to have quickly put him down.[11]

Vologases supported Emperor Pescennius Niger (r. 193–194) in his struggle for the Roman throne against Emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) in 192–193, during the Year of the Five Emperors. Furthermore, he also intervened in the affairs of the Roman vassal states in northern Mesopotamia—Adiabene and Osroene. Because of this, Septimius Severus, who emerged victorious in the struggle, attacked the Parthian Empire in 195.[12] Severus advanced into Mesopotamia, made Osroene a Roman province, and captured the Parthian capital Ctesiphon in 199.[1][12] At the same time, revolts were occurring in the Parthian provinces of Media and Pars.[13] Septimius Severus now declared himself Parthicus Maximus ("great victor in Parthia"). He was, however, unable to maintain his conquests, due to lack of food supplies and reinforcements. As a result, he withdrew his forces; during his withdrawal, he attempted in vain to conquer the Arab fortress of Hatra twice, later withdrawing his forces to Syria.[1]

In 202, peace was restored, reaffirming Roman rule in Armenia and northern Mesopotamia.[12] But, in the words of Iranologist Touraj Daryaee, "the dynasty [had] lost much of its prestige" and reached a "turning point".[13] The kings of Persis were now unable to depend on their weakened Arsacid overlords.[13] Indeed, in 205/6, Pabag, a local ruler in Persis, rebelled and overthrew his overlord Gochihr, taking the Persis capital Istakhr for himself.[13][14] His son Ardashir I would go on to continue his conquests, overthrowing the Parthian Empire and establishing the Sasanian Empire in 224.[15]

Vologases died in 208, succeeded by his son Vologases VI (r. 208–228), however another son, Artabanus IV (r. 216–224), attempted to seize the throne a few years later, resulting in a civil war.[1][16]

Notes

- ↑ According to the 5th-century Armenian historian Agathangelos, the king of Armenia had the second rank in the Parthian realm, below only to the Parthian king.[6] However the modern historian Lee E. Patterson suggests that Agathangelos may have exaggerated the importance of his homeland.[7]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chaumont & Schippmann 1988, pp. 574–580.

- 1 2 3 Toumanoff 1986, pp. 543–546.

- 1 2 Patterson 2013, pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Russell 1987, p. 161.

- ↑ Lang 1983, p. 517.

- ↑ Patterson 2013, pp. 180, 188.

- ↑ Patterson 2013, p. 188.

- ↑ Rapp 2014, p. 240.

- ↑ Rapp 2017, p. 240.

- ↑ Patterson 2013, p. 181 (see also note 18).

- ↑ Sellwood 1983, p. 297.

- 1 2 3 Dąbrowa 2012, p. 177.

- 1 2 3 4 Daryaee 2010, p. 249.

- ↑ Dąbrowa 2012, p. 187.

- ↑ Daryaee 2012, p. 187.

- ↑ Patterson 2013, p. 177.

Sources

- Chaumont, M. L.; Schippmann, K. (1988). "Balāš". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume III/6: Baḵtīārī tribe II–Banān. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 574–580. ISBN 978-0-71009-118-5.

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2012). "The Arsacid Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–432. ISBN 978-0-19-987575-7. Archived from the original on 2019-01-01. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2010). "Ardashir and the Sasanians' Rise to Power". Anabasis. University of California: 236–255.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2012). "The Sasanian Empire (224–651)". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199732159.

- Lang, David M (1983). "Iran, Armenia and Georgia". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 512–537. ISBN 0-521-20092-X..

- Patterson, Lee E. (2013). "Caracalla's Armenia". Syllecta Classica. Project Muse. 2: 27–61. doi:10.1353/syl.2013.0013. S2CID 140178359.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2014). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1472425522.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2017). "Georgia before the Mongols (2017)". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Oxford University Press: 1–39.

- Russell, James R. (1987). Zoroastrianism in Armenia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674968509.

- Sellwood, David (1983). "Parthian Coins". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 279–298. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Toumanoff, C. (1986). "Arsacids vii. The Arsacid dynasty of Armenia". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume II/5: Armenia and Iran IV–Art in Iran I. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 543–546. ISBN 978-0-71009-105-5.

Further reading

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2013). "Arsacid, Elymaean, and Persid Coinage". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.