Kassite Dynasty | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1595 BC – c. 1155 BC | |||||||||||||

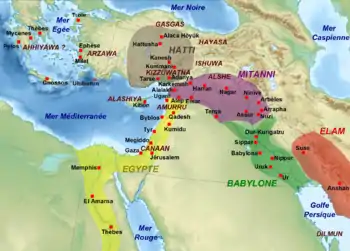

The Babylonian Empire under the Kassite Dynasty, c. 13th century BC. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Babylon | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian language | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

• c. 1531 BC | Agum II (first) | ||||||||||||

• c. 1157—1155 BC | Enlil-nadin-ahi (last) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient History | ||||||||||||

• Established | c. 1595 BC | ||||||||||||

| c. 1531 BC | |||||||||||||

• Invasions by Elam | c. 1155 BC | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 1155 BC | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Iraq | ||||||||||||

The Kassite dynasty, also known as the third Babylonian dynasty, was a line of kings of Kassite origin who ruled from the city of Babylon in the latter half of the second millennium BC and who belonged to the same family that ran the kingdom of Babylon between 1595 and 1155 BC, following the first Babylonian dynasty (Old Babylonian Empire; 1894-1595 BC). It was the longest known dynasty of that state, which ruled throughout the period known as "Middle Babylonian" (1595-1000 BC).

The Kassites were a people from outside Mesopotamia, whose origins are unknown, although many authors theorize that they originated in the Zagros Mountains. It took their kings more than a century to consolidate their power in Babylon under conditions that remain unclear. Despite their external origin, the Kassite kings did not change Babylon's ancestral traditions and, on the contrary, brought order to the country after the turbulence that marked the end of the first dynasty. Not being great conquerors, they undertook a great deal of construction work, notably on the great temples, they contributed to the expansion of agricultural land, and under their auspices Babylonian culture flourished and expanded throughout the Middle East. The Kassite period is still very poorly known, due to the scarcity of sources relating to it, of which few are published. The economic and social aspects, in particular, are very poorly documented, with the exception of what relates to the royal donations attested by the characteristic donation stelae of the period, the kudurrus.

During the term of the dynasty, Babylon's power was definitively established over all the ancient states of Sumer and Akkad, forming the country called "Karduniash" (Karduniaš). From the Kassites on, whoever wanted to dominate Mesopotamia had to reign in Babylon. This stability is remarkable because it is the only Babylonian dynasty whose power did not derive from the inheritance of one or two brilliant founding reigns followed by progressive decline.

Historical sources

Despite its long duration, the period of the dynasty is poorly documented: sources are scarce and few of them have been published. Architectural and artistic traces of this period are also scanty; they come mainly from the site of Dur-Kurigalzu, where the only monumental complex of the Kassite period was found, consisting of a palace and several cult buildings. Other buildings were discovered at several larger Babylonian sites, such as Nippur, Ur, and Uruk. Other minor sites belonging to the Kassite kingdom have also been discovered in the Hanrim hills: Tel Mohammed, Tel Inlie and Tel Zubeidi.[1][2] Further afield, at the site of Terca in the Middle Euphrates, and on the islands of Failaka (in what is now Kuwait) and Bahrain in the Persian Gulf, there are also some traces of Kassite rule. The low reliefs engraved on kudurrus and seal-cylinders are the best-known testimonies to the accomplishments of the artists of the time.[3]

From an epigraphic standpoint, J. A. Brinkman, a leading expert on sources from the period, has estimated that approximately 12,000 texts from the period have been found,[4][note 1] most of them belonging to the administrative archives from Nippur, of which only about 20% have been published.[note 2] They were found in American excavations carried out mainly during the late 19th century and are stored in Istanbul and Philadelphia. The rest come from other sites: there are forty tablets found at Dur-Kurigalzu that have been published,[5][6] others from Ur,[7][8][9] in the city of Babylon sets of private economic tablets and religious texts have been found that have not been published.[10] In the sites of the Hanrim hills, tablets have also been found, most of them unpublished,[note 3] and there are also tablets whose provenance is unknown (the "Peiser archive").[11][12] Most of this documentation is of an administrative and economic nature, but there are also some royal inscriptions and scholarly and religious texts.[13]

The royal inscriptions of the Kassite kings, few in number and generally brief, provide little information about the political history of their dynasty. It is necessary to turn to the later sources, which are the historical chronicles written in the early first millennium BC, the Synchronic History[14] and the P Chronicle,[15] which provide information mainly about the conflicts between the Kassite kings and the Assyrian kings.[16] The royal inscriptions of the latter, which are very abundant, provide essential information about the same wars.[17] The Elamite royal inscriptions are somewhat less reliable. To these sources are also added some letters from the diplomatic correspondence of the Kassite kings with Egypt[18] and the Hittites.[19] The former are part of the so-called Amarna Letters, found in Amarna, the ancient Akhetaten, capital of the pharaoh Akhenaten.[18] The latter were found at Boğazköy, on the site of the ancient Hittite capital, Hattusa.[19]

The type of textual source concerning the administrative and economic life of Kassite Babylon that has attracted the most attention of scholars is a form of royal inscription, found on stelae known as kudurrus (which the Babylonians called narû), commemorating royal donations. Some forty kudurrus are known from the Kassite period. Their texts usually consist of a brief description of the donation and any privileges, a long list of witnesses, and curses for those who did not respect the act.[20][21][22]

Political history

The unfamiliar beginning

In 1595 BC, Samsi-Ditana, king of Babylon, was defeated by Mursili I, king of the Hittites, who seized the statue of Marduk kept in the Esagila, the great temple of the city of Babylon, which he took with him. This defeat marked the end of the Babylonian Amorite dynasty, already greatly weakened by the various rivals, among them the Kassites. According to the Babylonian royal list, Agum II would have taken over Babylon after the city was sacked by the Hittites. According to the same source, Agum II would have been the tenth sovereign of the dynasty of the Kassite kings (founded by a certain Gandas), who would have reigned who knows where during the second half of the 18th century BC.[23] Possibly the Kassites were allied with the Hittites and supported their campaign to seize power.[24][25]

There are no mentions of the exact origin of the kassites in ancient texts.[note 4] The first mention of them dates from the 18th century BC in Babylon, but they are also mentioned in Syria and Upper Mesopotamia in the following centuries. However, most experts place their origin in the Zagros mountain range, where Kassites were still found during the first half of the first millennium BC.[26] The first Kassite sovereign attested as king of Babylon seems to be Burna-Buriash I. This dynasty had as its rival that of the Sea Country, located south of Babylon around the cities of Uruk, Ur and Larsa, which was defeated in the early 15th century BC by the Kassite sovereigns Ulamburiash and Agum III. After this military victory, Babylon's preponderance in southern Mesopotamia was not challenged again and the Kassite sovereigns dominated the entire territories of Sumer and Akkadia, which became the country of Karduniash (Karduniaš; the term Kassite equivalent to Babylon), which was one of the great powers of the Middle East.[27]

The only notable territorial gain made by Kassite rulers thereafter was the island of Bahrain, then called Dilmum, where a seal bearing the name of a Babylonian governor of the island was discovered, although nothing is known about the duration of this rule.[28]

Diplomatic relations

The 14th and 13th centuries BC marked the heyday of Babylon's Kassite dynasty. Its kings equaled their contemporary great sovereigns of Egypt, Hati, Mitanni and Assyria, with whom they maintained diplomatic relations, in which they have the privilege of bearing the title of "great king" (šarru rabû),[29] which involved abundant correspondence and exchanges of gifts (šulmānu).[note 5] This system, attested mainly by the Amarna letters[30][31] in Egypt and of Hatusa (the Hittite capital),[32] was ensured by emissaries called mār šipri, involved important exchanges of luxury goods, which included much gold and other precious metals, in a scheme of gifts and contradons, more or less respected by some sovereigns, which sometimes took place with some minor tensions. These exchanges were made as gifts of friendship or homage when a king was enthroned. The diplomatic language was Babylonian Akkadian, in the so-called "Middle Babylonian" form, as was the case in the preceding period.[33][34]

The courts of the regional powers of this period connected through dynastic marriages, and the Kassite kings took an active part in this process, establishing multi-generational ties with some courts, such as that of the Hittites (which possibly lay behind their seizure of power in the city of Babylon) and the Elamites. Burna-buriash II (ca. 1359-1333 BC) married one of his daughters to the pharaoh Akhenaten (3rd quarter of the 14th century BC)[35] and another to the Hittite king Suppiluliuma II, while he himself espoused the daughter of the Assyrian king Ashur-uballit I.[36] There were also Babylonian princesses who married Elamite sovereigns.[37] These practices were intended to strengthen the ties between the different royal houses, which in the last two cases were direct neighbors, in order to avoid political tensions. With more distant partners, such as the Hittites, they were essentially a form of prestige and influence, since the Babylonian princesses and the specialists (doctors and scribes) who were sent to the Hittite court were protagonists of Babylonian cultural influences in the Hittite kingdom.[38]

Say to Niburrereia (Tutankhamen?), king of Egypt, my brother: so (speaks) Burna-Buriash, king of Karduniash (Babylon), your brother. For me all is well. For you, for your house, your wives, your children, your country, your great ones, your horses, your chariots, may everything go well! Ever since my ancestors and yours proclaimed their friendship to each other, sumptuous gifts have been sent, and never has a request of any magnitude been refused. My brother has now sent me as a gift two mines of gold. Now, if the gold is in abundance, send me as much as your ancestors (sent), but if there is a lack of it, send me half of what your ancestors (sent). Why did you send me (only) two gold mines? Right now my temple work is very costly, and I have trouble completing it. Send me a lot of gold. And for your part, whatever you want for your country, write to me so that it can be sent to you.

— Testimony to a profitable friendship between Babylonian and Egyptian monarchs in a letter from Amarna

Conflicts with Assyria and Elam

Babylon became involved in a series of conflicts with Assyria when Assyrian ruler Ashur-uballit I broke free from Mithani rule in 1365 BC, which marked the beginning of a multi-secular confrontation between northern and southern Mesopotamia. Burna-Buriash II (r. ca. 1359-1333 BC) initially took a dim view of Assyrian independence, as he considered this region one of his vassals, but eventually married the daughter of the Assyrian king, with whom he had a son, Kara-hardash. The latter ascended the throne in 1333 BC, but was assassinated shortly thereafter and was succeeded by Nazi-Bugash. Ashur-uballit reacted to his grandson's murder and invaded Babylon to put his other grandson, Kurigalzu II (r. 1332-1308 BC) on the throne. The latter kept his allegiance to his grandfather until he died, but provoked the next Assyrian king Enlil-nirari, which led to a series of conflicts that lasted for over a century and culminated in the confrontation between Kashtiliash IV (r. 1232-1225 BC) of Babylon and Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. ca. 1243-1207 BC) of Assyria. The latter invaded and devastated Babylon, sacking the capital, from where he deported thousands of people.[39][40]

The situation then became increasingly confused, as the Assyrians failed to establish a lasting domination in Babylon, despite the will of Tukulti-Ninurta, who had his victory described in a long epic text (the Epic of Tukulti-Ninurta) and proclaimed himself king of Babylon. The conflicts continued and escalated when the Elamite king Kidin-Hutran (r. 1245-1215 BC) became involved, possibly in solidarity with the Kassite kings, to whom he was linked by marriage. Kidin-Hutran devastated Nippur and made the situation difficult for the Assyrian-imposed rulers in Babylon, who were deposed one after another until 1217 BC.[41]

After the assassination of Tukulti-Ninurta in 1208 BC and the internal turmoil that followed in Assyria, the kings of Babylon were able to regain their autonomy, to the extent that it was the Babylonian king Merodach-Baladan I (r. 1171-1159 BC) who helped the Assyrian king Ninurta-apil-Ecur take power in the northern kingdom, before the latter turned against him unsuccessfully.[42] Shortly after the end of these conflicts, the Elamite armies entered Mesopotamia, commanded by their king Shutruk-Nakhunte (r. 1185-1160 BC), at a time when Babylon and Assyria were weakened by recent warfare. The Elamite king's intervention in Babylon may have been motivated by his desire to assert his rights to the Babylonian throne resulting from his family ties to the Kassite dynasty, at a time when succession disputes had weakened the legitimacy of the Babylonian sovereigns.[43][44]

Fall of the Dynasty

In 1160 BC, at a time when Merodach-Baladan had managed to stabilize power in Babylon, the Elamite monarch Shutruk-Nakhunte invaded Babylon and sacked its major cities.It was during this period that several major monuments of Mesopotamian history were taken to Susa, the Elamite capital. Among the looted pieces were several statues and stelae, such as that of the victory of Naram-Sim of Akkad or the Code of Hammurabi, as well as other stelae from various eras, including kassite kudurrus. After several years of resistance led by Kassite sovereigns, the next Elamite king, Kutir-Nacunte III, dealt the coup de grace to the Kassite dynasty in 1155 BC and took the statue of the god Marduk to Elam as a symbol of Babylon's submission.[42]

Institutions of the Kassite kingdom

Documentation about the Kassite period is scant compared to the preceding period, focusing mainly on the 14th and 13th centuries BC. It has also been little studied, so little is known about the socioeconomic aspects of Babylon at that time. The largest body of documentation is a batch of 12,000 tablets found at Nippur, of which only a small part has been published and studied. A few archives have also been found elsewhere, but in small quantity. Added to these sources are the kudurrus (see below) and some royal inscriptions.[33][45]

The king

The Kassite king was designated by several titles. In addition to the more traditional "king of the four regions" or "king of totality" (šar kiššati), the new title "king of Karduniash" (šar māt karduniaš) was used, or the original "xacanacu of Enlil"[note 6][note 7] used by the two kings named Kurigalzu.[46] The first titles indicate that the king considered himself ruler of a territory that included the entire Babylonian region. The Kassite kings took up all the traditional attributes of the Mesopotamian monarchies: warrior kings,[47] supreme judges of the kingdom, and undertakers of works, notably the maintenance and restoration of the temples of the traditional Mesopotamian deities.[36] The entire royal family was involved in holding the high offices: there are examples of a king's brother commanding an army, or a king's son becoming the high priest of the god Enlil.[48]

Notwithstanding their ethnic background, the Kassite influences on the political and religious usages of the court seem to have been limited. The names of the sovereigns are Kassite at the beginning of the dynasty, referring to gods of this people, such as Burias, Harbe, or Marutas, but later mix Kassite and Akkadian terms. The royal dynasty placed itself under the protection of a pair of Kassite deities, Sucamuna and Sumalia, who had a temple in the city of Babylon at which kings were crowned.[49] Although, according to a text of the time, the official capital was later moved to Dur-Kurigalzu, the kings continued to be honored in Babylon, which preserved its status as the main capital. Dur-Kurigalzu was a new city founded by Kurigalzu II (r. 1332-1308 BC), where the Kassite kings were honored by the chiefs of the Kassite tribes. Apparently, this secondary capital seems to be more closely linked to the dynasty, without really shadowing Babylon, whose prestige remained intact.[50]

The elites of the royal administration

In the Kassite period some new titles appeared for dignitaries close to the king, such as šakrumaš, a term of Kassite origin that apparently designated a military chief, or the kartappu, who was originally a horse driver. Although the organization of the Kassite army is very poorly known, it is known that this period saw important innovations in military techniques, with the appearance of the light car and the employment of horses, which was apparently one of the Kassite specialties. Among the high dignitaries, the sukkallu (a vague term that can be translated as "minister") were still present. The roles of all these characters are ill-defined and probably unstable. The Kassite nobility is not well known, but it is generally admitted that they held the most important positions and had large estates.[51]

A little more is known about provincial administration.[52][53] The kingdom was divided into provinces (pīhatu), headed by governors, usually called šakin māti or šaknu, to which can be added the eventual tribal territories headed by a bēl bīti, an office we talk about below. The governor of Nippur bore the particular title of šandabakku (in Sumerian: GÚ.EN.NA) and had more power than the rest. This office of governor of Nippur is only well known because of the abundance of archives found in that city about the Kassite period. Governors often succeeded each other within the same family. At the local level, villages and towns were administered by a "mayor" (hazannu), whose functions had a judicial component, although there were judges (dayyānu).[54] The subordinate administrative posts were held by Babylonians, who were well trained for such tasks. The Kassites do not seem to have had much inclination for the profession of scribe-administrator. All subjects were obliged to pay taxes to the royal power, which in some cases could be paid with works: sometimes it happened that the administration requisitioned certain goods from private individuals. These tax contributions are known mainly because they are mentioned in the kudurrus, which record the exemption for certain lands.[54]

In the Kassite period some innovations were made in the field of administrative organization, which are partly due to Kassite traditions. Some territories were called "houses" (in Akkadian: bītu), headed by a chief (bēl bīti, "house chief"), who usually claimed to be descended from an eponymous common ancestor of the group. This was long interpreted as a kassite mode of tribal organization, with each tribe having a territory that it administered. This view has recently been challenged, and it has been proposed that these "houses" of family property inherited from an ancestor were a form of province that complemented the administrative grid described above, in which chiefs were appointed by the king.[55][56]

Royal donations

The dominant economic institutions in Babylon continued to be the "great bodies," the palaces and temples. But except for the case of the lands of the governor of Nippur, there is little documentation about these institutions. One of the rare aspects of the economic organization of the Kassidic period on which there is much documentation is that of the land grants made by the kings: there are thousands of unpublished tablets waiting to be published so that knowledge about this period can be expanded. This is a particular phenomenon that seems to have been initiated in this period, because during the previous period land was granted in a non-definitive way.[22][21][20][57]

These donations are recorded in kudurrus,[22][21][20][57] and 40 have been found from the Kassite dynasty. These are stelae divided into several sections: the description of the donation, with the rights and duties of the beneficiary (taxes, corvees, exemptions), the divine curses to which those who did not respect the donation were subjected, and often carved low reliefs. The kudurrus were placed in temples, under divine protection. Usually the donations involved very large properties, 80 to 1,000 hectares (250 ha on average) and the recipients were high dignitaries close to the king: high officials, members of the court, especially the royal family, generals or priests. They were a reward for people's loyalty or for acts for which they had distinguished themselves. The great temples of Babylon also received important estates: Esagila, the temple of Marduk of Babylon, received 5,000 ha during the period. The land was granted with agricultural workers, who became dependent on the temple. Sometimes the grants were accompanied by tax exemptions or corvees. In extreme cases, the beneficiaries had power over the local population, which took the place of the provincial administration, from which they were protected by special clauses.[note 8]

Some scholars see some similarities of this practice with feudalism,[note 9] which is flatly refuted by most recent studies, according to which these donations did not call into question the traditional Babylonian economic system, which was never feudal as such, although there may have been strong local powers on some occasions. The grants did not concern most of the land, which the sovereign could not alienate and which continued to be administered in the same ways as described above from previous periods.[58][59]

Economy

Agriculture

Very little is known about the economy of Kassite Babylon. The situation in the rural world is obscure as sources are very limited apart from what is known from kudurrus and some economic tables of the period from mainly Nippur. Archaeological surveys carried out in various areas of the Lower Mesopotamian plain indicate that economic recovery was slow after the crisis at the end of the Paleobylonian period, during which the number of occupied areas declined sharply. It is clear that there was a reoccupation of habitats, but this phenomenon focused mainly on small villages and rural settlements, which then became predominant, while urban sites that were previously predominant saw their area reduce, which may indicate a process of "ruralization" that marked a rupture in the history of the region.[60] This situation may have been accompanied by a decline in agricultural production, possibly aggravated in some regions (like Uruk, for example) by displacement of water courses.[61]

The land grants made by the kings seem to have focused mainly on lands located in the vicinity of cultivated areas, which may reflect a desire to take back areas that had become uncultivated after the end of the previous period. It is also noted that the royal administration engaged in the exploitation of intensively cultivated areas around Nippur.[62] However, little is even known about irrigated crops, the main economic sector of Babylon.[63]

Handicrafts and commercial exchanges

Very little is also known about local crafts and trade. In the archives of Dur-Kurigalzu there is a record of deliveries of raw materials such as metal and stone to craftsmen working for a temple,[6] a common situation in the organization of crafts in ancient Mesopotamia. Apparently, long-distance trade was quite developed, particularly with the Persian Gulf (Dilmun, in present-day Bahrain) and with the Mediterranean Levant. The Amarna Letters show that the king was interested in the fates of the Babylonian merchants as far as Palestine, but he cannot state whether this is an indication that these merchants (always called tamkāru) worked for the royal palace partially or completely.[64] The exchanges of goods carried out in the framework of diplomacy between the royal courts, although they cannot be identified as trade proper, did contribute to the circulation of goods on an international scale for the elites. Thus, the cordial diplomatic relations maintained by the Kassites with Egypt seem to have provided an important influx of gold to Babylon, which would have allowed prices to be based on the gold standard rather than silver for the first time in Mesopotamian history.[65]

Babylon exported to its western neighbors (Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia) lapis lazuli, which was imported from Afghanistan, and also horses whose breeding seems to have been a specialty of the Kassites, well attested in the Nippur texts, although these animals came from the mountainous regions of eastern and northeastern Mesopotamia.[66]

Religion and culture

Pantheon and places of worship

The Mesopotamian pantheon of the Kassite period did not undergo profound changes from the preceding period. This can be seen in the low relief of a kudurru from Meli-Shipak II (1186-1172 B.C.) currently preserved in the Louvre Museum.[67] The deities invoked as guarantors of the land grant that is consecrated on this stele are represented according to a functional and hierarchical organization. On the upper part are symbols of the deities that traditionally dominated the Mesopotamian pantheon: Enlil, who remained the king of the gods, Anu, Sin, Shamash, Ishtar and Enki. The Kassite sovereigns adopted Mesopotamian religious usages and traditions, but the cultural preponderance of the city of Babylon and the growing importance of the clergy of its main temple, the Esagila, tended to make the city's tutelary god, Marduk, an increasingly important deity in the Babylonian pantheon by the end of the Kassite period.[68] His son Nabu, god of wisdom, and Gula, goddess of medicine, also enjoyed great popularity.[3]

The original Kassite deities did not acquire an important place in the Babylonian pantheon. The main ones are known through a few mentions in the texts: the patron couple of the Sucamuna-Sumalia dynasty already mentioned, the storm god Burias, the warrior god Marutas, the sun god Surias, and Harbe, who seems to have had a sovereign function.[3]

The various works sponsored in the temples by the Kassite monarchs are poorly known at the architectural level, but there are indications that some innovations were made.[69] A small temple with original decoration built inside Eanna, the main religious complex of Uruk, is known to have been constructed during the reign of Caraindas (15th century BC), and of works carried out at Ebabar, the temple of the god Shamash in Larsa, during the reign of Burna-Buriash II (ca. 1359-1333 BC). However, it is mainly one of two kings named Kurigalzu (probably the first, who reigned in the early 14th century BC) who is known, among other works, for building or rebuilding several temples in the main cities of Babylon, namely in the major religious centers (Babylon, Nippur, Akkadia, Kish, Sippar, Ur and Uruk), in addition to the city he founded, Dur-Kurigalzu, where a ziggurat dedicated to the god Enlil was built. Besides these works, Kurigalzu sponsored the worship of the deities worshipped in these different temples. Resuming the traditional role of Babylonian kings as protectors and funders of the cult of the gods, the Kassite kings played a crucial role in restoring the normal functioning of many of these shrines that had ceased to function following the abandonment of several major sites in southern Babylon at the end of the Paleobylonian Period, such as Nippur, Ur, Uruk and Eridu.[61]

Writings from the Kassite period

The school texts from the Kassite period found at Nippur show that the learning structures of the scribes and the literates remained similar to those of the Paleobylonian period.[70][71] However, a major change took place: texts in Akkadian were included in the school curricula, which kept pace with the evolution of Mesopotamian literature, which increasingly became written in that language, although Sumerian continued to be used. The Kasside period also saw the development of "Standard Babylonian," a literary form of Akkadian that remained fixed in the following centuries in literary works and can therefore be considered a "classic" form of the language. From then on, new Mesopotamian literary works were written exclusively in this dialect.[33]

During the Kassite period, several fundamental works of Mesopotamian literature were written and there was mainly the canonization and standardization of works from previous periods that until then had circulated under various variants. Akkadian versions of some Sumerian myths were also prepared.[72] The Kassite period seems to have enjoyed prestige among the literates of the following periods, who sometimes looked for an ancestor among the literates who were supposed to have been active during this period.[73] Important achievements of this period include the writing of canonical versions of numerous lexical lists,[74] the writing of a "Hymn to Shamash," one of the most notable in ancient Mesopotamia, as well as another dedicated to Gluttony. The standard version of the "Epic of Gilgamesh," which according to tradition is by the exorcist Sîn-lēqi-unninni, is often attributed to this same period. However, precise dating of the literary works is often impossible: at best, these achievements can be placed in the period between 1400 and 1000 BC.[75][76]

One of the most remarkable aspects of the literature of the Middle Babylonian period is the fact that several works reflect a deepening of reflections on human destiny, in particular the relations between gods and men. This is found in several major works of Mesopotamian sapiential literature, a genre that had existed for a millennium, but which then reached its full maturity and proposed deeper reflections.[77] The Ludlul bel nemeqi ("I will praise the Lord of Wisdom"; also known as "Poem of the Just Sufferer" and "Monologue of the Just Sufferer," "Praise to the Lord of Wisdom," or "Babylonian Job") presents a just and pious man who laments over his misfortunes whose cause he does not understand, for he respects the gods. The Dialogue of Pessimism, written after the Kassite period, proposes a similar reflection in the form of a satirical dialogue. The changes leading to the standard version of the Epic of Gilgamesh would also reflect these developments: whereas the previous version accentuated mainly the heroic aspect of Gilgamexe, the new version seems to introduce a reflection on human destiny, in particular on the inevitability of death.[75][76]

Architectural and artistic achievements

As with other cultural aspects, the arrival of the Kassites did not change Babylonian architectural and artistic traditions, although some developments did occur.[3][78]

A few housing blocks from this period have been uncovered in the Babylonian sites at Ur, Nippur, and Dur-Kurigalzu, where no major changes from the preceding period have been noted. In contrast, the religious architecture, although poorly known, seems to witness some innovations.[69] The small shrine built under the Caraindas of the Eanna complex at Uruk has a facade decorated with molded baked bricks representing deities protecting the waters, a type of ornamentation that is an innovation of the Kassite period. However, official architecture is mainly represented in Dur-Kurigalzu, a new city ordered built by one of the kings named Kurigalzu, where the large size of the main buildings shows that a new phase of monumentality has been entered.[79][80]

In that city, a part of a vast palace complex 420,000 m2 (4,500,000 sq ft) in area, organized around eight units, was uncovered.[81] Each of the sections of this building may have been assigned to the main Kassite tribes. According to a text of the time, the palace of Dur-Kurigalzu was the place where these tribes formally recognized the power of the new kings when they ascended the throne, which happened after the coronation had taken place in the city of Babylon, which remained the main capital.[50] Some of the rooms were decorated with paintings, fragments of which have been found, including scenes of processions of male characters, who are identified as dignitaries of the Kassite tribes.[82] Southeast of the palace was a religious complex dedicated to Enlil, dominated by a ziggurat whose ruins still stand over 57 meters high. Other temples were also built on this site.[83]

The stone sculpture of the Kassite period is represented mainly by the low reliefs decorating the kudurrus already mentioned several times, whose iconography is particularly interesting.[84] In them are symbols of the deities that guarantee the legal acts recorded on the stela, which are considerably developed by the artists of this period and replace the anthropomorphic representations of the deities, which allowed many deities to be represented in a minimum space. Nevertheless, sculptors continue to make figurative representations of characters on these stelae, as was common in previous periods. A kudurru from Meli-Shipak represents this king holding hands with his daughter, to whom he made the donation of property recorded in the stela text, and presenting her to the goddess Nanaia, guarantor of the act, who is seated on a throne. Above are depicted the symbols of the astral deities Sin (Crescent Moon), Shamash (solar disk) and Ishtar (morning star, Venus).[67]

The use of vitreous materials developed greatly during the second half of the second millennium BC, with the enamelled glass technique in various colors (blue, yellow, orange and brown), which was used to produce glaze-covered clay vases and architectural elements, of which the tiles and bricks found at Acar Cufe are a good example. The first forms of glass also appeared in this period, and are represented in the artistic field by vases decorated with mosaics.[85][86][87]

The glyptic themes experienced various evolutions during the second half of the second millennium BC, which experts divide into three or four types but whose chronology and geographical distribution are still poorly determined. The type of seal that predominated at the beginning took up the tradition of the preceding period; it associates a seated and a praying deity, with the text accompanying the image, very developed, consisting of a votive prayer; the engraved material is generally a hard stone. The next type of the kassite period is more original; a central character is depicted, often a kind of kthonic figure, a god on a mountain or emerging from the waters, or a hero, a demon, or trees surrounded by genies. The third kassite type is characterized by Assyrian influences and the presence of real or hybrid animals. The later style (also called "pseudo-Kassite"), developed at the end of the Kassite period or shortly thereafter, was engraved on soft stones and the images were dominated by animals associated with trees and framed with friezes of triangles.[88][89][90][91]

List of kings of the Kassite Dynasty

Note: the list is uncertain until Agum II, at least. The dates are approximate.

- Gandas (2nd half of the 18th century BC)

- Agum I

- Kashtiliash I

- Usssi

- Abiratash

- Kashtiliash II

- Urzigurumas

- Harbasiu

- Tipetaquezi

- Agum II (took power in Babylon at the end of the 16th century BC)

- Burna-Buriash I

- Kashtiliash III

- Ulamburiash (early 15th century BC)

- Agum III

- Kadashman-Harbe I

- Karaindash (15th century BC)

- Kurigalzu I

- 1374–1360 BC: Kadashman-Enlil I

- 1359–1333 BC: Burna-Buriash II

- 1333 BC: Kara-hardash

- 1333 BC: Nazi-Bugash

- 1332–1308 BC: Kurigalzu II

- 1307–1282 BC: Nazi-Maruttash

- 1281–1264 BC: Kadashman-Turgu

- 1263–1255 BC: Kadashman-Enlil II

- 1254–1246 BC: Kudur-Enlil

- 1246–1233 BC: Shagarakti-Shuriash

- 1232–1225 BC: Kashtiliash IV

- 1224 BC: Enlil-nadin-shumi

- 1223 BC: Kadashman-Harbe II

- 1222–1217 BC: Adad-shuma-iddina

- 1216–1187 BC: Adad-shuma-usur

- 1186–1172 BC: Meli-Shipak II

- 1171–1159 BC: Marduk-apla-iddina I

- 1158 BC: Zababa-shuma-iddin

- 1157–1155 BC: Enlil-nadin-ahi

References

- ↑ Invernizzi (1980)

- ↑ Boehmer & Dammer (1985)

- 1 2 3 4 Stein (1997, pp. 273–274)

- ↑ Brinkman (1974, p. 395)

- ↑ Gurney (1949)

- 1 2 Gurney (1983)

- ↑ Gurney (1974a)

- ↑ Gurney (1974b)

- ↑ Gurney (1983)

- ↑ André-Salvini (2008, pp. 102–103)

- ↑ Peiser & Kohler (1905)

- ↑ Brinkman (1974, p. 46)

- ↑ Stein (1997, p. 272)

- ↑ "ABC 21 (Synchronic Chronicle)". Livius.org. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ↑ "ABC 22 (Chronicle P)". Livius.org. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ↑ Glassner (1993, pp. 170–178, 223–227)

- ↑ Grayson (1987)

- 1 2 Amarna Letters, EA 1 & EA 15.

- 1 2 Beckman (1999, pp. 132–137)

- 1 2 3 Slanski (2003a)

- 1 2 3 Charpin (2004, pp. 169–191)

- 1 2 3 Brinkman (2006)

- ↑ Astour (1986, pp. 327–331)

- ↑ Richardson (2005, pp. 273–289)

- ↑ Freu, Klock-Fontanille & Mazoyer (2007, pp. 111–117)

- ↑ Potts (2006, pp. 112–114)

- ↑ Lion, B. "Cassites (rois)". In Joannès (2001), p. 164.

- ↑ Lombard (1999, pp. 122–125)

- ↑ Liverani (2000, pp. 15–24)

- ↑ Moran (1987)

- ↑ Liverani (1998–1999)

- ↑ Beckman (1999, p. )

- 1 2 3 Lion, B. "Médio-babylonien". In Joannès (2001), p. 523.

- ↑ Beckman, G. "International Law in the Second Millennium: Late Bronze Age". In Westbrook (2003), pp. 765–766..

- ↑ Amarna letters, EA 13 & EA 14.

- 1 2 Lion, B. "Cassites (rois)". In Joannès (2001), p. 165.

- ↑ van Dijk (1986)

- ↑ Bryce, T. "A View from Hattusa". In Leick (2007), pp. 503–514..

- ↑ Garelli et al. (1997, pp. 200–206)

- ↑ Galter, H. D. "Looking Down the Tigris, The interrelations between Assyria and Babylonia". In Leick (2007), pp. 528–530..

- ↑ Potts (1999, pp. 230–231)

- 1 2 Garelli & Lemaire (2001, pp. 44–45)

- ↑ Potts (1999, pp. 232–233)

- ↑ Goldberg (2004)

- ↑ Slanski (2003, pp. 485–487).

- ↑ Brinkman (1974, p. 405)

- ↑ Brinkman (1974, pp. 399–402)

- ↑ Slanski (2003, pp. 487–489).

- ↑ Brinkman (1974, p. 404)

- 1 2 Meyer (1999, pp. 317–326)

- ↑ Brinkman (1974, p. 402)

- ↑ Brinkman (1974, pp. 406–407)

- ↑ Slanski (2003, pp. 488–489).

- 1 2 Slanski (2003, p. 490).

- ↑ Sassmannshausen (2000, pp. 409–424)

- ↑ Richardson (2007, pp. 25–26)

- 1 2 Sommerfeld (1995a, pp. 920–922)

- ↑ Sommerfeld (1995b, pp. 467–490)

- ↑ Lafont (1998, pp. 575–577)

- ↑ Richardson (2007, pp. 16–17)

- 1 2 Adams & Nissen (1972, pp. 39–41)

- ↑ Nashef (1992, pp. 151–159)

- ↑ van Soldt (1988, pp. 105–120)

- ↑ Brinkman (1974, pp. 397–399)

- ↑ Edzard (1960)

- ↑ Vermaark, P. S. "Relations between Babylonia and the Levant during the Kassite period". In Leick (2007), pp. 520–521..

- 1 2 "Kudurru du roi Meli-Shipak II" (in French). Louvre Museum.

- ↑ Oshima, T. "The Babylonian god Marduk". In Leick (2007), p. 349..

- 1 2 Margueron (1991, pp. 1181–1187)

- ↑ Sassmannshausen (1997)

- ↑ Veldhuis (2000)

- ↑ Joannès (2003, pp. 23–25)

- ↑ Lambert (1957)

- ↑ Taylor, J. E. "Babylonian lists of words and signs". In Leick (2007), pp. 437–440..

- 1 2 George (2003, p. 28)

- 1 2 George, Andrew R. "Gilgamesh and the literary traditions of ancient Mesopotamia". In Leick (2007), pp. 451–453..

- ↑ Lambert (1996, pp. 14–17)

- ↑ Klengel-Brandt, E. "La culture matérielle à l'époque kassite". In André-Salvini (2008), pp. 110–111..

- ↑ al-Khayyat (1986)

- ↑ Clayden (1996, pp. 112–117)

- ↑ Margueron (1982, pp. 451–458 e fig. 328–330)

- ↑ Tomabechi (1983)

- ↑ Margueron (1991, p. 1107)

- ↑ Demange, F. "Les kudurrus, un type de monument kassite?". In André-Salvini (2008), pp. 112–115; 118–121..

- ↑ Caubet (2008)

- ↑ "Faïences antiques" (2005)

- ↑ Sauvage, M.; Joannès, F. "Verre". In Joannès (2001), pp. 909–910..

- ↑ Stein (1997, p. 274)

- ↑ Matthews (1990)

- ↑ Matthews (1992)

- ↑ Collon, D. "Babylonian Seals". In Leick (2007), pp. 107–110..

Notes

This article was originally translated, in whole or in part, from the French Wikipedia article.

- ↑ Brinkman (1974) is a currently dated work, but remains fundamental for the presentation of the sources of this period.

- ↑ The publication of much of the published texts is in Sassmannshausen (2001), the only recent publication of a corpus of sources from Nippur, which doubled the number of texts from the Kassite period published.

- ↑ These Hanrim mound tablets are mentioned, for example, in Kessler (1982).

- ↑ About the Kassite people and their history, see Zadok (2005).

- ↑ On the international relations of this period see the overviews of Liverani (1990) and Bryce (2003).

- ↑ Xacanacu was a title originally used in the Akkadian Empire (24th- 21st century BC) meaning "governor." The rulers of Mari (now Syria) in the period following the independence of that city during the collapse of the Akkadian Empire adopted it as their royal title, so it is often associated with those rulers, whose lineage, ruling until the end of the third millennium BC, is called the "Dynasty of the Xacanacus". in Dossin (1940)

- ↑ Enlil was one of the main gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon.

- ↑ On economic and social analysis of the content of these donations, see Oelsner (1981, pp. 403–410) and Oelsner (1982, pp. 279–284)

- ↑ Kemal Balkan explicitly refers to the alleged parallelism between feudalism and the cassite donation system in his work Studies in Babylonian Feudalism of the Kassite Period, which remains one of the most extensive studies on the social and economic situation of that period. in Balkan (1986)

Bibliography

- Adams, Robert McCormick; Nissen, Hans Jörg (1972). The Uruk Countryside: The Natural Setting of Urban SocietiesThe Uruk Countryside: The Natural Setting of Urban Societies. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226005003.

- André-Salvini, Béatrice, ed. (2008). Babylone (in French). Paris: Hazan - Musée du Louvre éditions. ISBN 9782754102834. expo.

- Astour, M. (1986), "The name of the ninth Kassite ruler", Journal of the American Oriental Society, New Haven American Oriental Society, 106 (2): 327–331, doi:10.2307/601597, ISSN 0003-0279, JSTOR 601597, OCLC 1480509

- Balkan, Kemal (1986). Studies in Babylonian Feudalism of the Kassite Period. Undena Publications. ISBN 9780890031933.

- Alexa Bartelmus and Katja Sternitzke, "Karduniaš: Babylonia under the Kassites. The Proceedings of the Symposium held in Munich 30 June to 2 July 2011 / Tagungsbericht des Münchner Symposiums vom 30. Juni bis 2. Juli 2011", Volume 1 Karduniaš. Babylonia under the Kassites 1, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2017 ISBN 9781501511639 https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501503566

- Alexa Bartelmus and Katja Sternitzke, "Karduniaš: Babylonia under the Kassites. The Proceedings of the Symposium held in Munich 30 June to 2 July 2011 / Tagungsbericht des Münchner Symposiums vom 30. Juni bis 2. Juli 2011", Volume 2 Karduniaš. Babylonia under the Kassites 2, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2017, ISBN 9781501512162 https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501504242

- Beckman, Gary M. (January–April 1983). "Mesopotamians and Mesopotamian Learning at Hattuša". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 35 (1–2): 97–114. doi:10.2307/3515944. hdl:2027.42/77476. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 3515944. OCLC 1782513. S2CID 163616298.

- Beckman, Gary M. (1999). Hittite Diplomatic Texts. Scholars Press. ISBN 9780788505515.

- Boehmer, R. M.; Dammer, H.-W. (1985). Tell Imlihiye, Tell Zubeidi, 'Tell Abbas (in German). Mainz: P. von Zabern.

- Brinkman, John Anthony (1974). "The Monarchy in the Time of Kassite Dynasty". In Garelli, Paul (ed.). Le Palais et la Royauté (Archéologie et civilisation). Paris: Paul Geuthner. pp. 395–408.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1976). Materials and Studies for Kassite History: A catalogue of cuneiform sources pertaining to specific monarchs of the Kassite dynasty. Vol. 1. Oriental institute of the University of Chicago.

- Brinkman, J. A. (2006). "Babylonian Royal Land Grants, Memorials of Financial Interest, and Invocation of the Divine". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. Leida: Brill. 49 (1): 1–47. doi:10.1163/156852006776207242. ISSN 0022-4995. OCLC 6009613.

- Bryce, Trevor R. (2003). Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East: The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age. Routledge. ISBN 9781134575855.

- Caubet, A. (2008). "Babylone, Naissance d'une légende". Les Dossiers d'archéologie (in French): 35–42. ISSN 1141-7137.

- Charpin, Dominique (2004). "Chroniques bibliographiques. 2, La commémoration d'actes juridiques: à propos des kudurrus babyloniens". Revue Assyriologique (in French).

- Clayden, T. (1996). "Kurigalzu I and the Restoration of Babylonia". Iraq. British School of Archaeology in Iraq. 58: 109–121. doi:10.2307/4200423. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200423. OCLC 1714824.

- Cohen, Y. (2004). "Kidin-Gula - The Foreign Teacher at the Emar Scribal School". Revue Assyriologique: 81–100.

- Curtis, John (1995). Later Mesopotamia and Iran: Tribes and Empires, 1600-539 BC: Proceedings of a Seminar in Memory of Vladimir G. Lukonin. Londres: British Museum Press. ISBN 9780714111384.

- van Dijk, J. (1986). "Die dynastischen Heiraten zwischen Kassiten und Elamern: eine verhängnisvolle Politik". Orientalia. Nova Series (in German). Pontificio Istituto Biblico. Facoltà di Studi dell'Antico Oriente. 55 (2): 159–170. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43075392. OCLC 456502479.

- Dossin, Georges (1940). "Inscriptions de fondation provenant de Mari". Syria (in French). Institut français du Proche-Orient. 21 (2): 152–169. doi:10.3406/syria.1940.4187. ISSN 0039-7946. S2CID 191465937.

- Edzard, D. O. (1960). "Die Beziehungen Babyloniens und Ägyptens in der mittelbabylonischen Zeit und das Gold". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (in German). Brill: 38–55. ISSN 0022-4995. OCLC 6009613.

- Freu, Jacques; Klock-Fontanille, Isabelle; Mazoyer, Michel (2007). Des origines à la fin de l'ancien royaume hittite: Les Hittites et leur histoire (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782296167155.

- Garelli, Paul; Durand, Jean-Marie; Gonnet, Hatice; Breniquet, Catherine (1997). Le Proche-Orient asiatique, tome 1: Des origines aux invasions des peuples de la mer [The Asian Middle East, volume 1: From the origins to the invasions of the sea peoples]. Nouvelle Clio (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 9782130737193. OCLC 7292355675 – via Google Books. (1969 ed. via Internet Archive)

- Garelli, Paul; Lemaire, André (2001). Le Proche-Orient Asiatique, tome 2: Les empires mésopotamiens, Israël (in French). Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 9782130520221.

- George, A. R. (2003). "Sîn-leqi-unninni and the Standart Gigames Epic". The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199278411.

- Glassner, Jean-Jacques (1993). Chroniques mésopotamiennes (in French) (2nd ed.). Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 9782251339184.

- Goldberg, J. (2004). "The Berlin Letter, Middle Elamite Chronology and Sutruk-Nahhunte I's Genealogy". Iranica Antiqua. Leida: Brill. 39: 33–42. doi:10.2143/IA.39.0.503891. ISSN 0021-0870.

- Grayson, A. K. (1987). The Royal inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian periods. Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennium B.C. (To 1115 B.C.). University of Toronto Press.

- Gurney, O. R. (1949). "Texts from Dur-Kurigalzu". Iraq. British School of Archaeology in Iraq. 11 (1): 131–149. doi:10.2307/4241691. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4241691. OCLC 1714824. S2CID 163670183.

- Gurney, O. R. (1974a). Middle Babylonian Legal Documents and Other Texts. London: Trustees of the British Museum and of the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania.

- Gurney, O. R. (1974b). Ur Excavations Texts VII. London: British Museum Publications.

- Gurney, O. R. (1983). The Middle Babylonian Legal land Economic Texts from Ur. Oxford: British School of Archaeology in Iraq. ISBN 9780903472074. OCLC 13359170.

- Invernizzi, A. (1980). Excavations in the Yelkhi Area (Hamrin Project, Iraq). Vol. 15. Universidade de Turim. pp. 19–49. ISSN 0076-6615. OCLC 310136669.

- Izre`el, Shlomo (1997). The Amarna Scholarly Tablets. Groningen: Brill. ISBN 9789072371836.

- Joannès, Francis (2001). Joannès (ed.). Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne (in French) (Paris ed.). Robert Laffont. ISBN 9782702866573.

- Joannès, F. (2003). "Le Code d'Hammurabi et les trésors du Louvre. La littérature mésopotamienne". Les Dossiers d'archéologie. 288. ISSN 1141-7137.

- al-Khayyat, A. A. (1986). "La Babylonie: Aqar Quf: capitale des Cassites". Dossiers Histoires et Archéologie (in French). 103: 59–61. ISSN 0299-7339. OCLC 436700634.

- Kessler, K. (1982). "Kassitische Tontafeln von Tell Imlihiye". Baghdader Mitteilungen (in German). Deutsches Archöologisches Institut. Abteilung Baghdad. 13: 51–116. ISSN 0418-9698.

- Klein, Jacob; Skaist, Aaron Jacob, eds. (1990). Bar-Ilan Studies in Assyriology dedicated to Pinḥas Artzi. Bar-Ilan University Press. ISBN 9789652261007.

- Lafont, S. (1998). "Fief et féodalité dans le Proche-Orient ancien". In Bournazel, Éric; Poly, Jean-Pierre (eds.). Les féodalités (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 9782130636595.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1957). "Ancestors, Authors and Canonicity". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. Cambridge, Massachusetts: American Schools of Oriental Research. 11 (1): 1–14. doi:10.2307/1359284. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1359284. OCLC 1782513. S2CID 164095626.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1996). Babylonian Wisdom Literature. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464942.

- Leick, Gwendolyn, ed. (2007). The Babylonian World. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781134261284.

- Liverani, Mario (1990). Prestige and interest: international relations in the Near East ca. 1600-1100 B.C. Padua: Sargon.

- Liverani, M. (1998–1999). Le lettere di el-Amarna (2 vol.) (in Italian). Padua: Le littere di el-Amarna. ISBN 9788839405661.

- Liverani, M. (2000). "The Great Powers' Club". In Cohen, Raymond; Westbrook, Raymond (eds.). Amarna Diplomacy, The Beginning of International Relations. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801871030.

- Lombard, P. (1999). "L'occupation des Kassites de Mésopotamie". Bahreïn, La civilisation des deux mers (in French). Paris: Institut du Monde Arabe.

- Margueron, Jean-Claude (1982). Recherches sur les palais mésopotamiens de l'âge du bronze (in French). Paris: P. Geuthner.

- Margueron, Jean-Claude (1991). "Sanctuaires sémitiques". Supplément au Dictionnaire de la Bible, fasc. 64 B-65 (in French). Paris: Letouzey et Ané.

- Matthews, Donald M. (1990). Principles of Composition in Near Eastern Glyptic of the Later Second Millennium B.C. Fribourg: Universitätsverlag. ISBN 9783525536582.

- Matthews, Donald M. (1992). The Kassite Glyptic of Nippur. Fribourg: Universitätsverlag. ISBN 9783727808074.

- Meyer, Jan-Waalke (1999). "Der Palast von Aqar Quf: Stammesstrukturen in der kassitischen Gesellschaft". In Böck, Barbara; Cancik-Kirschbaum, E.; Richter, T.; Renger, Johannes (eds.). Munuscula Mesopotamica, Festschrift für Johannes Renger (in German). Münster: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9783927120815.

- Moran, William L. (1987). Les lettres d'El-Amarna: correspondance diplomatique du pharaon (in French). Paris: Editions du Cerf. ISBN 9782204026451.

- Nashef, K. (1992). "The Nippur Countryside in the Kassite Period". In Ellis, Maria deJong (ed.). Nippur at the Centennial: Papers Read at the 35e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Philadelphia, 1988. S.N. Kramer Fund, Babylonian Section, University Museum. ISBN 9780924171017.

- Oelsner, J. (1981). "Zur Organisation des gesellschaftlichen Lebens im kassitischen und nachkassitischen Babylonien: Verwaltungsstruktur und Gemeinschaften". In Hirsch, H.; Hunger, H. (eds.). Vorträge gehalten auf der 28 Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale in Wien, 6.-10 Juli 1981 (in German). Vienna: Institut für Orientalistik der Universität Wien.

- Oelsner, J. (1982). "Landvergabe im kassitischen Babylonien". In Dandamayev, M. A.; Gershevitch, I.; Klengel, H.; Komoróczy, G.; Larsen, M. T.; Postgate, J. N. (eds.). Societies and Languages in the Ancient Near East: Studies in Honour of I.M. Diakonoff (in German). Warminster: Aris and Phillips.

- Paulus, Susanne; Clayden, Tim (2020). Babylonia under the Sealand and Kassite Dynasties. Berlin et Boston: De Gruyter.

- Paulus, Susanne (2022). "Kassite Babylonia". In Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller et Daniel T. Potts (ed.). The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East, Volume 3: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 801–868.

- Peiser, Felix Ernst; Kohler, Josef (1905). Urkunden aus der Zeit der dritten babylonischen Dynastie (in German). Berlin: W. Peiser.

- Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521564960.

- Potts, D. T. (2006). "Elamites and Kassites in the Persian Gulf". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. Journal of Near Eastern Studies: University of Chicago. Department of Oriental Languages and Literatures. 65 (2): 111–119. doi:10.1086/504986. ISSN 0022-2968. S2CID 162371671.

- Richardson, S. (2005). "Trouble in the Countryside, ana tar?i Samsuditana: Militarism, Kassites, and the Fall of Babylon I". In Kalvelagen, R.; van Soldt, W. H.; Katz, Dina (eds.). Ethnicity in Ancient Mesopotamia: Papers Read at the 48th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale Leiden, 1-4 July 2002. Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 9789062583133.

- Richardson, S. "The World of the Babylonian Countrysides". In Leick (2007).

- Sassmannshausen, Leonhard (1997). "Mittelbabylonische Runde Tafeln aus Nippur". Baghdader Mitteilungen (in German). Mainz: Deutsches Archöologisches Institut. Abteilung Baghdad. 28: 185–208. ISSN 0418-9698. OCLC 564591813.

- Sassmannshausen, L. (2000). "The Adaptation of the Kassites to the Babylonian Civilization". In van Lerberghe, Karel; Voet, Gabriela (eds.). Languages and Cultures in Contact: At the Crossroads of Civilizations in the Syro-Mesopotamian Realm; Proceedings of the 42th RAI. Leuven: Peeters Press. ISBN 9789042907195.

- Sassmannshausen, L. (2001). Beiträge zur Verwaltung und Gesellschaft Babyloniens in der Kassitenzeit (in German). Mainz: von Zabern. ISBN 9783805324717.

- Slanski, Kathryn. "Middle Babylonian Period". In Westbrook (2003)..

- Slanski, Kathryn E. (2003a). The Babylonian Entitlement Narûs (kudurrus): A Study in Their Form and Function. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. ISBN 9780897570602.

- Sommerfeld, Walter (1995a). "The Kassites of Ancient Mesopotamia: Origins, Politics and Culture". In Sasson, Jack M. (ed.). Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. New York: Scribner. pp. 917–930.

- Sommerfeld, Walter (1995b). "Der babylonische `Feudalismus´". In Dietricht, M.; Loretz, O.; von Soden, Wolfram (eds.). Vom Alten Orient Zum Alten Testament: Festschrift für Wolfram Freiherrn von Soden (in German). Neukirchen-Vluyn: Butzon & Bercker. ISBN 9783766699770.

- van Soldt, W. H. (1988). "Irrigation in Kassite Babylonia". Irrigation and cultivation in Mesopotamia Part I. Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture. Vol. IV. Cambridge: Sumerian Agriculture Group. pp. 104–120. ISSN 0267-0658.

- van Soldt, W. H. (1995). "Babylonian Lexical, Religious and Literary Texts and Scribal Education at Ugarit and its Implications for the Alphabetic Literary Texts". In Dietrich, Manfried; Loretz, Oswald (eds.). Ein ostmediterranes kulturzentrum im Alten Orient: Ergebnisse und Perspektiven der Forschung. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 9783927120174.

- Stein, Diana L. (1997). "Kassites (Mesopotamian peoples)". In Meyers, Eric M. (ed.). Oxford Encyclopaedia of Archaeology in the Ancient Near East. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. pp. 271–275.

- Tomabechi, Y. (1983). "Wall Paintings from Dur Kurigalzu". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. University of Chicago. Department of Oriental Languages and Literatures. 42 (2): 123–131. doi:10.1086/373002. ISSN 0022-2968. S2CID 161783796.

- van der Toorn, Karel (2000). "Cuneiform Documents from Syria-Palestine: Textes, Scribes, and Schools". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. Deutscher verein zur Erforschung Palästinas. 116 (2): 97–113. ISSN 0012-1169. JSTOR 27931644. OCLC 6291473.

- Trokay, M. (1998). "Relations Artistiques entre Hittites et Kassites" [Artistic Relations between Hittites and Kassites]. In Erkanal, H. (ed.). XXXIVème Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale [XXXIVth International Assyriological Meeting] (in French). Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi 1998 [Turkish Historical Society Printing House].

- Veldhuis, N. (2000). "Kassite Exercises: Literary and Lexical Extracts". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. Cambridge, Massachusetts: American Schools of Oriental Research. 52: 67–94. doi:10.2307/1359687. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1359687. OCLC 1782513. S2CID 162919544.

- Westbrook, Raymond, ed. (2003). "A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law". Handbuch der Orientalistik. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill.

- Zadok, R. (2005). "Kassites". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. XVI, Fasc. 2. pp. 113–118. ISSN 2330-4804.

- "Faïences antiques". Les Dossiers d'archéologie (in French). 304: 14–18, 29–31. 2005. ISSN 1141-7137.