Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom Kushanshahr First period c. 230 CE–c. 365 CE Second period 565 CE–651 CE | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

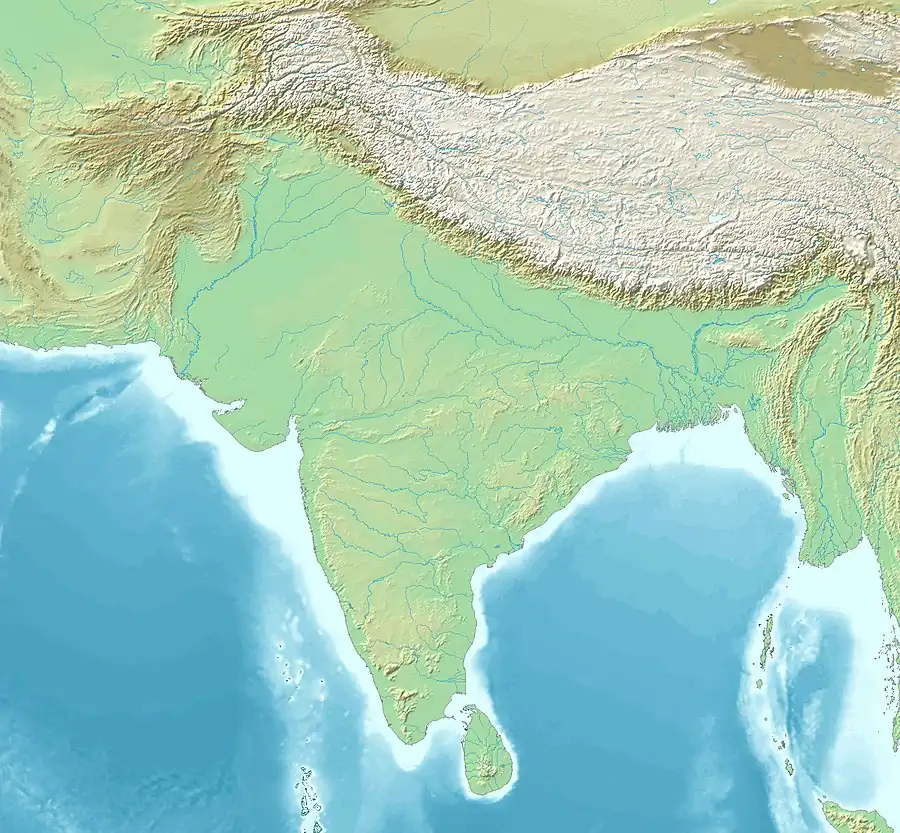

.png.webp)  ◁ ▷ Territory of the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom, with contemporary neighbouring polities | |||||||||||

Map of the domains governed by the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom | |||||||||||

| Capital | Balkh | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Persian Bactrian | ||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism Zoroastrianism Hinduism | ||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom (or Indo-Sasanians) was a polity established by Sasanian Persians in Bactria during the 3rd and 4th centuries CE. The Sasanian Empire captured the provinces of Sogdiana, Bactria and Gandhara from the declining Kushan Empire following a series of warsin 225 CE.[1] The local Sasanian governors then went on to take the title of Kushanshah (KΟÞANΟ ÞAΟ or Koshano Shao in the Bactrian language[2]) or "King of the Kushans", and to mint their own coins.[1] They are sometimes considered as forming a "sub-kingdom" inside the Sasanian Empire.[3] This administration continued until 360-370 CE,[1] when the Kushano-Sasanians lost much of their domains to the invading Kidarite Huns, whilst the rest was incorporated into the imperial Sasanian Empire.[4] Later, the Kidarites were in turn displaced by the Hephthalites.[5] The Sasanians were able to re-establish some authority after they destroyed the Hephthalites with the help of the Turks in 565, but their rule collapsed under Arab attacks in the mid 7th century.

The Kushanshas are mainly known through their coins. Their coins were minted at Kabul, Balkh, Herat, and Merv, attesting the extent of their realm.[6]

A rebellion of Hormizd I Kushanshah (277–286 CE), who issued coins with the title Kushanshahanshah ("King of kings of the Kushans"), seems to have occurred against contemporary emperor Bahram II (276–293 CE) of the Sasanian Empire, but failed.[1]

History

First Kushano-Sassanid period (230-365 CE)

The Sassanids, shortly after victory over the Parthians, extended their dominion into Bactria during the reign of Ardashir I around 230 CE, then further to the eastern parts of their empire in western Pakistan during the reign of his son Shapur I (240–270). Thus the Kushans lost their western territory (including Bactria and Gandhara) to the rule of Sassanid nobles named Kushanshahs or "Kings of the Kushans". The farthest extent of the Kushano-Sasanians to the east appears to have been Gandhara, and they apparently did not cross the Indus river, since almost none of their coinage has been found in the city of Taxila just beyond the Indus.[7]

The Kushano-Sasanians under Hormizd I Kushanshah seem to have led a rebellion against contemporary emperor Bahram II (276-293 CE) of the Sasanian Empire, but failed.[1] According to the Panegyrici Latini (3rd-4th century CE), there was a rebellion of a certain Ormis (Ormisdas) against his brother Bahram II, and Ormis was supported by the people of Saccis (Sakastan).[6] Hormizd I Kushanshah issued coins with the title Kushanshahanshah ("King of kings of the Kushans"),[8] probably in defiance of imperial Sasanian rule.[1]

Around 325, Shapur II was directly in charge of the southern part of the territory, while in the north the Kushanshahs maintained their rule. Important finds of Sasanian coinage beyond the Indus in the city of Taxila only start with the reigns of Shapur II (r.309-379) and Shapur III (r.383-388), suggesting that the expansion of Sasanian control beyond the Indus was the result of the wars of Shapur II "with the Chionites and Kushans" in 350-358 as described by Ammianus Marcellinus.[7] They probably maintained control until the rise of the Kidarites under their ruler Kidara.[7]

350 CE

The decline of the Kushans and their defeat by the Kushano-Sasanians and the Sasanians, was followed by the rise of the Kidarites and then the Hephthalites (Alchon Huns) who in turn conquered Bactria and Gandhara and went as far as central India. They were later followed by Turk Shahi and then the Hindu Shahi, until the arrival of Muslims to north-western parts of India.

Second Sassanid period (565-651 CE)

The Hephthalites dominated the area until they were defeated in 565 CE by an alliance between the First Turkic Khaganate and the Sasanian Empire, and some Sassanid authority was re-established in eastern lands. According to al-Tabari, Khosrow I managed, through his expansionist policy, to take control of "Sind, Bust, Al-Rukkhaj, Zabulistan, Tukharistan, Dardistan, and Kabulistan".[9]

The Hephthalites were able to set up rival states in Kapisa, Bamiyan, and Kabul, before being overrun by the Tokhara Yabghus and the Turk Shahi. The Sasanians may also have expelled by the Nezak-Alchons.[10] The 2nd Indo-Sassanid period ended with the collapse of Sassanids to the Rashidun Caliphate in the mid 7th century. Sind remained independent until the Arab invasions of India in the early 8th century.

Religious influences

Obv: King Varhran I with characteristic head-dress.

Rev: Shiva with bull Nandi, in Kushan style.

Coins depicting Shiva and the Nandi bull have been discovered, indicating a strong influence of Shaivite Hinduism.

The prophet Mani (210–276 CE), founder of Manichaeism, followed the Sassanids' expansion to the east, which exposed him to the thriving Buddhist culture of Gandhara. He is said to have visited Bamiyan, where several religious paintings are attributed to him, and is believed to have lived and taught for some time. He is also related to have sailed to the Indus valley area now in modern-day Pakistan in 240 or 241 AD, and to have converted a Buddhist King, the Turan Shah of India.[11]

On that occasion, various Buddhist influences seem to have permeated Manichaeism: "Buddhist influences were significant in the formation of Mani's religious thought. The transmigration of souls became a Manichaean belief, and the quadripartite structure of the Manichaean community, divided between male and female monks (the 'elect') and lay follower (the 'hearers') who supported them, appears to be based on that of the Buddhist sangha".[11]

Coinage

The Kushano-Sassanids created an extensive coinage with legend in Brahmi, Pahlavi or Bactrian, sometimes inspired from Kushan coinage, and sometimes more clearly Sassanid.

The obverse of the coin usually depicts the ruler with elaborate headdress and on the reverse either a Zoroastrian fire altar, or Shiva with the bull Nandi.

Kushano-Sasanian ruler Ardashir I Kushanshah, circa 230-250 CE. Merv mint.

Kushano-Sasanian ruler Ardashir I Kushanshah, circa 230-250 CE. Merv mint.

Indo-Sassanid coin.

Indo-Sassanid coin. A gold Indo-Sassanid coin.

A gold Indo-Sassanid coin.

Kushano-Sasanian art

The Indo-Sassanids traded goods such as silverware and textiles depicting the Sassanid emperors engaged in hunting or administering justice.

Kushano-Sasanian footed cup with medallion, 3rd-4th century CE, Bactria, Metropolitan Museum of Art.[13]

Kushano-Sasanian footed cup with medallion, 3rd-4th century CE, Bactria, Metropolitan Museum of Art.[13] Possible Kushano-Sasanian plate, excavated in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, 350-400 CE.[14] British Museum 124093.[15][16]

Possible Kushano-Sasanian plate, excavated in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, 350-400 CE.[14] British Museum 124093.[15][16].jpg.webp) Terracotta head of a male figure, Kushano-Sasanian period, Gandhara region, 4th-5th century CE

Terracotta head of a male figure, Kushano-Sasanian period, Gandhara region, 4th-5th century CE

Artistic influences

The example of Sassanid art was influential on Kushan art, and this influence remained active for several centuries in the northwest South Asia. Plates seemingly belonging to the art of the Kushano-Sasanians have also been found in Northern Wei tombs in China, such as a plate depicting a boar hunt found in the 504 CE tomb of Feng Hetu.[20]

Vishnu Nicolo Seal: Kushano-Sasanian or Kidarite prince worshipping Vishnu or Vāsudeva, with Bactrian inscription. Found in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. 4th century CE. British Museum.[21][22][23]

Vishnu Nicolo Seal: Kushano-Sasanian or Kidarite prince worshipping Vishnu or Vāsudeva, with Bactrian inscription. Found in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. 4th century CE. British Museum.[21][22][23] Sasanian dignitary drinking wine, on ceiling of Cave 1, at Ajanta Caves, India, end of the 5th century.[24]

Sasanian dignitary drinking wine, on ceiling of Cave 1, at Ajanta Caves, India, end of the 5th century.[24]

Main Kushano-Sassanid rulers

The following Kushanshahs were:[25]

- Ardashir I Kushanshah (230–245)

- Peroz I Kushanshah (245–275)

- Hormizd I Kushanshah (275–300)

- Hormizd II Kushanshah (300–303)

- Peroz II Kushanshah (303–330)

- Varahran Kushanshah (330-365)

See also

| History of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3, E. Yarshater p.209 ff

- ↑ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2021). "From the Kushans to the Western Turks". King of the Seven Climes: 204.

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas, Cambridge University Press, 2014 p.284 ff

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017b, p. 83.

- ↑ Sasanian Seals and Sealings, Rika Gyselen, Peeters Publishers, 2007, p.1

- 1 2 Encyclopedia Iranica

- 1 2 3 Ghosh, Amalananda (1965). Taxila. CUP Archive. pp. 790–791.

- 1 2 CNG Coins

- ↑ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 125–156. ISBN 9781474400312.

- ↑ ALRAM, MICHAEL (2014). "From the Sasanians to the Huns New Numismatic Evidence from the Hindu Kush". The Numismatic Chronicle. 174: 282. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 44710198.

- 1 2 Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ↑ For the precise date: Sundermann, Werner; Hintze, Almut; Blois, François de (2009). Exegisti Monumenta: Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 284, note 14. ISBN 978-3-447-05937-4.

- ↑ "Plate British Museum". The British Museum.

- ↑ Sims, Vice-President Eleanor G.; Sims, Eleanor; Marshak, Boris Ilʹich; Grube, Ernst J.; I, Boris Marshak (January 2002). Peerless Images: Persian Painting and Its Sources. Yale University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-300-09038-3.

- ↑ Carter, M.L. "Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

A gilt silver plate depicting a princely boar hunt, excavated from a tomb near Datong dated to 504 CE, is close to early Sasanian royal hunting plates in style and technical aspects, but diverges enough to suggest a Bactrian origin dating from the era of the Kushano-Sasanian rule (ca. 275-350 CE)

- ↑ HARPER, PRUDENCE O. (1990). "An Iranian Silver Vessel from the Tomb of Feng Hetu". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 4: 51–59. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24048350.

- ↑ Watt, James C. Y. (2004). China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

- ↑ Carter, M.L. "Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

A gilt silver plate depicting a princely boar hunt, excavated from a tomb near Datong dated to 504 CE, is close to early Sasanian royal hunting plates in style and technical aspects, but diverges enough to suggest a Bactrian origin dating from the era of the Kushano-Sasanian rule (ca. 275-350 CE)

- ↑ "Seal British Museum". The British Museum.

- ↑ "a Sasanian prince is represented adoring before the Indian god Vishnu" in Herzfeld, Ernst (1930). Kushano-Sasanian Coins. Government of India central publication branch. p. 16.

- ↑ "South Asia Bulletin: Volume 27, Issue 2". South Asia Bulletin. University of California, Los Angeles. 2007. p. 478:

A seal inscribed in Bactrian , fourth to fifth century AD , shows a Kushano - Sasanian or Kidarite official worshipping Vishnu : Pierfrancesco Callieri , Seals and Sealings from the North - West of the Indian Subcontinent and Afghanistan.

- ↑ The Buddhist Caves at Aurangabad: Transformations in Art and Religion, Pia Brancaccio, BRILL, 2010 p.82

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017b, p. 78.

Sources

- Cribb, Joe (2018). Rienjang, Wannaporn; Stewart, Peter (eds.). Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd-24th March, 2017. University of Oxford The Classical Art Research Centre Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-78491-855-2.

- Cribb, Joe (2010). Alram, M. (ed.). "The Kidarites, the numismatic evidence.pdf". Coins, Art and Chronology Ii, Edited by M. Alram et al. Coins, Art and Chronology II: 91–146.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017a). "The Sasanian Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 978-0-692-86440-1.

- Payne, Richard (2016). "The Making of Turan: The Fall and Transformation of the Iranian East in Late Antiquity". Journal of Late Antiquity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 9: 4–41. doi:10.1353/jla.2016.0011. S2CID 156673274.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2014). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. London: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4724-2552-2.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017b). "East Iran in Late Antiquity". ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 978-1-4744-0030-5. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8. (registration required)

- Rypka, Jan; Jahn, Karl (1968). History of Iranian literature. D. Reidel. ISBN 9789401034791.

- Sastri, Nilakanta (1957). A Comprehensive History of India: The Mauryas & Satavahanas. Orient Longmans. p. 246. ISBN 9788170070030.

- Vaissière, Étienne de La (2016). "Kushanshahs i. History". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Wiesehöfer, Joseph (1986). "Ardašīr I i. History". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 4. pp. 371–376.