Second Turkic Khaganate 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰃𐰠 Türük el | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 682–744 | |||||||||||||||||||

Approximate map of Second Turkic Khaganate, 720 AD. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Khaganate (Nomadic empire) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Otuken (summer camp) Yarγan yurtï (winter camp)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Turkic (official)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism (official)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Hereditary monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Khagan | |||||||||||||||||||

• 682 – 691 | Elteriš Qaghan | ||||||||||||||||||

• 691 – 716 | Qapγan Qaghan | ||||||||||||||||||

• 716 | İnäl Qaghan | ||||||||||||||||||

• 716 – 734 | Bilgä Qaghan | ||||||||||||||||||

• 744 | Ozmıš Qaghan | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tarkhan | |||||||||||||||||||

• 682 – 716 | Tonyukuk | ||||||||||||||||||

• 716 – 731 | Kul Tigin | ||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Kurultay | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 682 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 744 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

Court of Seljuk ruler Tughril III, circa 1200 CE. |

The Second Turkic Khaganate (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰃𐰠, romanized: Türük el, lit. 'State of the Turks',[4] Chinese: 後突厥; pinyin: Hòu Tūjué, known as Turk Bilge Qaghan country (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰝:𐰋𐰃𐰠𐰏𐰀:𐰴𐰍𐰣:𐰃𐰠𐰭𐰀, romanized: Türük Bilgä Qaγan eli) in Bain Tsokto inscriptions)[5] was a khaganate in Central and Eastern Asia founded by Ashina clan of the Göktürks that lasted between 682–744. It was preceded by the Eastern Turkic Khaganate (552–630) and the early Tang dynasty period (630–682). The Second Khaganate[6][7][8] was centered on Ötüken in the upper reaches of the Orkhon River. It was succeeded by its subject Toquz Oghuz confederation, which became the Uyghur Khaganate.

Outline

A few decades after the fall of Eastern Turkic Khaganate (630), Ashina Nishufu was declared qaghan in 679 but soon revolted against the Tang dynasty.[9] In 680, he was defeated by Pei Xingjian. Shortly afterwards, Nishufu was killed by his men.[9] Following Nishufu's death, Ashina Funian, another scion of the royal clan, was made qaghan and the Eastern Turks once again rebelled against Tang rule.[10] The early stages of the rebellion brought about some victories for Funian, however later, Turks were once again defeated by Pei Xiangjin.[10] According to Tonyukuk, the attempt to revolt against the Tang and set a qaghan on the throne was legitimate action. It was the people's fault that they deposed and killed Nishufu, and subduing themselves again to the Tang dynasty.[11]

The uprising in 679–681 was at first unsuccessful, although it led, in 682, to the withdrawal of Qutlugh into the Gobi desert. Once they had established themselves in the Yin Mountains, Qutlugh, his brother Bögü-chor, and his closest comrade-in-arms, Tonyukuk succeeded in winning the support of most of the Turks and conducted successful military operations against the imperial forces in Shanxi between 682 and 687. In 687 Ilterish Qaghan left the Yin Shan mountains and turned his united and battle-hardened army to the conquest of the Türk heartlands in modern-day central and northern Mongolia. Between 687 and 691 Toquz Oghuz and the Uyghurs, who had occupied these territories, were routed and subjugated. Their chief, Abuz kaghan, fell in battle. The centre of the Second Turkic Khaganate shifted to the Otuken mountains, and the rivers Orkhon, Selenga and Tola.[12]

Rise

In 691 Ilterish Qaghan died and was succeeded by his younger brother, who assumed the title Qapaghan Qaghan. In 696–697 Qapaghan subjugated the Khitans and sealed an alliance with the Kumo Xi (Tatabï in Turkic texts), which stemmed the advance of the Tang armies to the northeast, into the foothills of the Khingan, and secured the empire's eastern frontier. Between 698 and 701 the northern and western frontiers of Qapaghan's state were defined by the Tannu Ola, Altai and Tarbagatai mountain ranges. After defeating the Bayirku tribe in 706–707, the Türks occupied lands extending from the upper reaches of the Kerulen to Lake Baikal. In 709–710 the Türk forces subjugated the Az and the Chik, crossed the Sayan mountains (Kögmen yïš in Turkic texts), and inflicted a crushing defeat on the Yenisei Kyrgyz. The Kyrgyz ruler, Bars beg, fell in battle, and his descendants were to remain vassals of the Göktürks for several generations. In 711 the Türk forces, led by Tonyukuk, crossed the Altai Mountains, clashed with the Türgesh army in Dzungaria on the River Boluchu, and won an outright victory. Tonyukuk forced a crossing over the Syr Darya in pursuit of the retreating Türgesh, leading his troops to the border of Tokharistan. However, in battles with the Arabs near Samarkand the Türk forces were cut off from their rear services and suffered considerable losses; they had difficulty in returning to the Altai in 713–714. There they reinforced the army that was preparing to besiege Beshbalik. The siege was unsuccessful and, after losing in six skirmishes, the Türks lifted it.[13]

Crisis

.jpg.webp)

In violation of custom, the throne was taken by Qapaghan's son Inel Qaghan (716). Inel, who had no right to the throne, and his supporters, were killed by Kul Tigin, who had support of many Turkic families, and set on the throne his elder brother Bilge Qaghan, who ruled from 716 to 734.[14]

Bilge Qaghan mounted the throne at a time when the empire founded by his father was on the verge of collapse. The western lands seceded for good, and immediately after the death of Qapagan, the Türgesh leader Suluk proclaimed himself kaghan. The Kitan and Tatabi tribes refused to pay tribute, the Toquz Oghuz revolt continued, and the Türk tribes themselves began to rebel. Feeling unable to control the situation, Bilge kaghan offered the throne to his brother, Kul Tigin. The latter, however, would not go against the legal order of succession. Then, at last, Bilge decided to act. Kul Tigin was put at the head of the army, and Tonyukuk, who had great authority among the tribes, became the kaghan's closest adviser.

In 720 Emperor Xuanzong of Tang attacked but Tonyukuk defeated his Basmyl cavalry and the Turks pushed into Gansu. Next year Xuanzong bought him off. In 727 he received 100,000 pieces of silk in return for a 'tribute' of 30 horses. He refused to ally with the Tibet Empire against the Tang dynasty. His wisdom was praised by Zhang Yue (Tang dynasty).

Decline

.png.webp)

The deaths of Tonyukuk (726) and Kul Tigin (731) removed Bilge's best advisors. It is reported that Bilge was killed by poison, but the poison was slow-acting and he managed to kill his murderers before he died. Bilge was followed by his elder son Yollig Khagan, and later Yollig was succeeded by his brother Tengri Qaghan. After the death of Tengri Qaghan, the empire began to disintegrate. The Ashina tribe was less and less able to cope with central power. The young Tengri kaghan was killed by his uncle, Kutlug Yabghu, who seized power. War broke out with the tribal groups of the Uyghurs, the Basmils and the Karluks, and Kutluk Yabgu Khagan and his followers perished in the fighting.

Defeat

Kutlug I Bilge Kagan of Uyghurs allied himself with the Karluks and Basmyls, and defeated the Göktürks. In 744 Kutlug seized Ötüken and beheaded the last Göktürk qaghan, Ozmish Qaghan. His head was sent to the Tang court.[15] In the span of a few years, the Uyghurs gained mastery of Inner Asia and established the Uyghur Khaganate. Kulun Beg succeeded his father Ozmish. The Tang emperor Xuanzong decided to destroy the last traces of the Turkic khaganate and sent general Wang Zhongsi Kulun's forces. Meanwhile, Ashina Shi was deposed by Kutlug Bilge Qaghan. Wang Zhongsi, defeated the eastern flank of Turkic army headed by Apa Tarkhan. Although Kulun Beg tried to escape, he was arrested by the Uyghurs and was beheaded just like his father in 745. Most of the Turks fled to other Turkic tribes like Basmyl. However, a group including Qutluğ Säbäg Qatun, Bilge Khagan's widow, and Tonyukuk's daughter, took refuge in the Tang dynasty. The Tang emperor legitimised her as a princess and she was appointed as the ruler of her people.[16]

Rulers of the Second Turkic Khaganate

Khagans

| Khagan | reign | father, grandfather |

Regnal name

(Chinese reading) |

Personal name

(Chinese reading) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ilterish Qaghan | 682–692 | Etmish Beg, unknown |

Xiédiēlìshī Kèhán | 阿史那骨篤祿 Āshǐnà Gǔdǔlù |

| Qapaghan Qaghan | 692–716 | Etmish Beg, unknown |

Qiānshàn Kèhán | 阿史那默啜 Āshǐnà Mòchuài |

| Inel Qaghan | 716–717 | Qapaghan Qaghan, Etmish Beg |

Tàxī Kèhán | 阿史那匐俱 Āshǐnà Fújù |

| Bilge Qaghan | 717–734 | Ilterish Qaghan, Etmish Beg |

Píjiā Kèhán | 阿史那默棘連 Āshǐnà Mòjílián |

| Yollıg Khagan | 734–739 | Bilge Qaghan, Ilterish Qaghan |

Yīrán Kèhán | 阿史那伊然 Āshǐnà Yīrán |

| Tengri Qaghan | 739–741 | Bilge Qaghan, Ilterish Qaghan |

Dēnglì Kèhán | 阿史那骨咄 Āshǐnà Gǔduō |

| Ozmish Qaghan | 742–744 | Pan Kul Tigin, Ashina Duoxifu |

Wūsūmǐshī Kèhán | 阿史那乌苏米施 Āshǐnà Wūsūmǐshī |

Interregnum (741-745)

| Khagans | reign | father, grandfather |

Regnal name

(Chinese reading) |

Personal name

(Chinese reading) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kutluk Yabgu Khagan (usurper) |

741–742 | Unknown (not Ashina) |

N/A | Gǔduō Yèhù |

| Ashina Shi (claimant, Basmyl chief) |

742–744 | Uti beg, Ashina Duoxifu |

Hèlà Píjiā Kèhán | Yīdiēyīshī |

| Kulun Beg (claimant) |

744–745 | Özmiş Khagan, Pan Kul Tigin |

Báiméi Kèhán | Ashina Gulongfu |

- Later claimants

- Eletmish Kagan 747–759[17] (Son of Ashina Duoxifu)

- Bügü Kagan 759–779[17]

Political and social structure

Under Ilterish, the traditional structure of the Turkic state was restored. The empire created by Ilterish and his successors was a territorial union of ethnically related and hierarchically co-ordinated tribes and tribal groups. They were ideologically linked by common beliefs and accepted genealogies, and politically united by a single military and administrative organization (el) and by general legal norms (törü). The tribal organization (bodun) and the political structure (el) complemented one another, defining the strength and durability of social ties. In the words of the Türk inscriptions, the khan controlled the state and was head of the tribal group (el tutup bodunïm bašladïm). The principal group in the empire was composed of twelve Turkic tribes headed by the dynastic tribe of the Ashina.[19] Next in political importance were the Toquz Oghuz.[20]

Economy

The basis of the economy of the Türk tribes was nomadic cattle-raising. Organized hunting in the steppes and mountains was of military as well as economic significance: during these hunts the warriors were trained and the various detachments were coordinated. A Chinese chronicler describes the economy and way of life of the Türks thus: "They live in felt tents and wander following the water and the grass". Horses were of vital importance to the Türks. Although the economy rested on cattle-raising, winter feed for livestock was not stored. The advantage of the horse was that it could be at grass all the year round, feeding even under a light cover of snow. Sheep and goats followed the horses, eating the grass that they themselves would have been unable to clear of snow. Bulls, yaks and camels are also frequently mentioned in Türk texts as valuable items of livestock.[21]

Religion

Tengrism was the official religion of the Second Turkic Khaganate. Khagans believed that ruling Ashina family gained legitimacy "through its support from Tengri".[22] Chinese sources state that Bilge wanted to convert to Buddhism and establish cities and temples. However, Tonyukuk discouraged him from this by pointing out that their nomadic lifestyle was what made them a greater military power when compared to Tang dynasty.[23] While Turks' power rested on their mobility, conversion to Buddhism would bring pacifism among population. Therefore, sticking to Tengriism was necessary to survive.[24][25]

Relations

Tang dynasty

Orkhon inscription

While I have ruled here, I have become reconciled with the Chinese people. The Chinese people, who give in abundance gold, silver, millet, and silk, have always used ingratiating words and have at their disposal enervating riches. While ensnaring them with their ingratiating talk and enervating riches, they have drawn the far-dwelling peoples nearer to themselves. But after settling down near them these we have come to see their cunning.[26]

Sogdia

Camels, women, girls, silver, and gold were seized from Sogdia during a raid by Qapaghan Qaghan.[27]

Bain Tsokto inscription

The whole Sogdian people leading by Asuk came and obeyed. Those days the Turkish people reached the Iron Gates.[28]

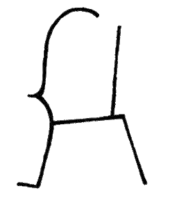

Old Turkic: 𐰦𐰀:𐰘𐰼𐰝𐰃:𐰽𐰀:𐰉𐰽𐰞𐰍𐰺𐰆:𐰺𐰑𐰴:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣:𐰸𐰆𐰯:𐰚𐰠𐱅𐰃:𐰆𐰞:𐰚𐰇𐰤𐱅𐰀:𐱅𐰏𐱅𐰃:𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰝:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣:𐱅𐰢𐰼:𐰴𐰯𐰍𐰴𐰀:𐱅𐰃𐰤𐰾𐰃:𐰆𐰍𐰞𐰃, romanized: Anta berüki As-oq baslïγaru Soγdaq budun qop kelti jükünti ..tegti Türük budun Temir Qapïγqa Tensi oγulï.

Works of art and artifacts

Numerous artifacts of gold and silver are known from the graves of the rulers of the Second Turkic Khaganate.

Silver Deer of Bilge Khan from the burial site at Khoshoo Tsaidam.

Silver Deer of Bilge Khan from the burial site at Khoshoo Tsaidam..jpg.webp) Silver tableware from Kul Tigin's burial site at Khoshoo Tsaidam.

Silver tableware from Kul Tigin's burial site at Khoshoo Tsaidam..jpg.webp) Silver vessels from Kul Tigin's burial site at Khoshoo Tsaidam.

Silver vessels from Kul Tigin's burial site at Khoshoo Tsaidam..jpg.webp)

References

Citations

- ↑ Newly discovered Old Turkic runic inscription of the Ulaanchuluut Mountain (Red Mountain) from the Central Mongolia On the basis of the Mongol-Japanese International Epigraphical Expedition in August 2018, Osawa Takashi

- ↑ David Prager Branner, (2006), The Chinese Rime Tables: Linguistic philosophy and historical-comparative phonology

- ↑ Empires, Diplomacy, and Frontiers. (2018). In N. Di Cosmo & M. Maas (Eds.), Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750 (pp. 269-418). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

"...some scholars see this practice as amounting to a state religion, “Tengrism,” in which the ruling Ashina family gained legitimacy through its support from Tengri." - ↑ Sigfried J. de Laet, Ahmad Hasan Dani, Jose Luis Lorenzo, Richard B. Nunoo Routledge, 1994, History of Humanity, p. 56

- ↑ Aydın (2017), p. 119

- ↑ Elena Vladimirovna Boĭkova, R. B. Rybakov, Kinship in the Altaic World: Proceedings of the 48th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Moscow 10–15 July 2005, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-447-05416-4, p. 225.

- ↑ Anatoly Michailovich Khazanov, Nomads and the Outside World, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0-299-14284-1, p. 256.

- ↑ András Róna-Tas, An introduction to Turkology, Universitas Szegediensis de Attila József Nominata, 1991, p. 29.

- 1 2 Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 202 (in Chinese)

- 1 2 Pan, Yihong (1997). "Chapter 8: China, the Second Turkish Empire and the Western Turks, 679-755". Son of Heaven and Heavenly Qaghan: Sui-Tang China and Its Neighbors. Bellingham, WA: Center for East Asian Studies, Western Washington University. p. 262. ISBN 9780914584209.

- ↑ Mihaly Dobrovits, TEXTOLOGICAL STRUCTURE AND POLITICAL OF THE OLD TURKIC RUNIC INSCRIPTIONS, p. 151

- ↑ Barfield, Thomas J. The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China. Cambridge, Mass.: B. Blackwell, 1989. Print.

- ↑ Klyashtorny, 1964, pp. 35–40.

- ↑ Liu 2006, p. 330-331

- ↑ Grousset 114.

- ↑ L.M. Gumilev, (2002), Eski Türkler, translation: Ahsen Batur, ISBN 975-7856-39-8, OCLC 52822672, p. 441-564 (in Turkish)

- 1 2 Yu. Zuev (I︠U︡. A. Zuev) (2002) (in Russian), Early Türks: Essays on history and ideology (Rannie ti︠u︡rki: ocherki istorii i ideologii), Almaty, Daik-Press, p. 233, ISBN 9985-4-4152-9.

- ↑ SKUPNIEWICZ, Patryk (Siedlce University, Poland) (2017). Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets.The headgear in Iranian history volume I: Pre-Islamic Period. Siedlce-Tehran: K. Maksymiuk & G. Karamian. p. 253.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Czeglédy, 1972, pp. 275–81.

- ↑ Czeglédy, 1982, pp. 89–93.

- ↑ D. Sinor and S. G. Klyashtorny, The Türk Empire, p. 338

- ↑ Empires, Diplomacy, and Frontiers. (2018). In N. Di Cosmo & M. Maas (Eds.), Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750 (pp. 269-418).

- ↑ Denis Sinor (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, vol.1, Cambridge University Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9, 312–313.

- ↑ Wenxian Tongkao, 2693a

- ↑ Ercilasun 2016, pp. 295-296

- ↑ Ross, E. (1930). The Orkhon Inscriptions: Being a Translation of Professor Vilhelm Thomsen's final Danish rendering. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 5(4), 861-876.

- ↑ Tekin, 1968, 289

- ↑ Lucie Šmahelová, (1958), Kül-Tegin monument. Turkic Khaganate and research of the First Czechoslovak-Mongolian expedition in Khöshöö Tsaidam 1958, p. 100

- ↑ G, Reza Karamian; Farrokh, Kaveh; Syvänne, Ilkka; Kubik, Adam; Czerwieniec-Ivasyk, Marta; Maksymiuk, Katarzyna. Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets The headgear in Iranian history volume I: Pre-Islamic Period Edited by Katarzyna Maksymiuk & Gholamreza Karamian Siedlce-Tehran 2017. p. 1252.

- ↑ "National History Museum of Mongolia". September 7, 2019.

Sources

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

|

- Christoph Baumer, History of Central Asia, volume 2, pp255–270. The other usual sources (Grousset, Sinor, Christian, UNESCO have summaries)

- Lev Gumilyov, The Ancient Turks, 1967 (long account in Russian at: )

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)