Mes Aynak

مس عينک | |

|---|---|

Remains of a Buddhist monastery at Mes Aynak | |

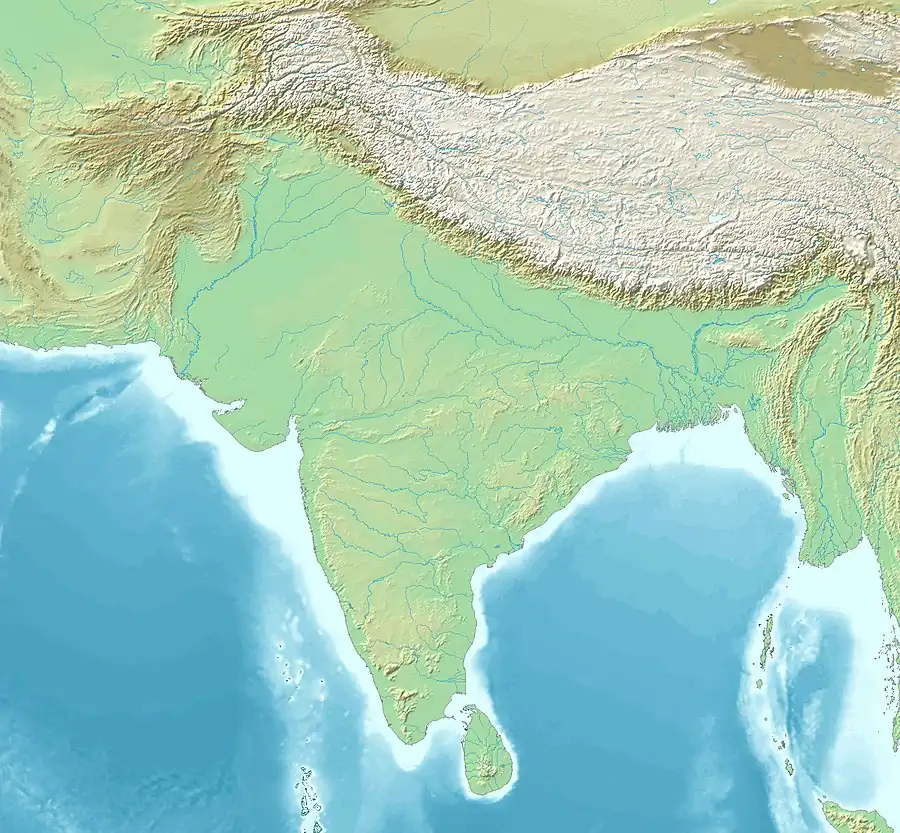

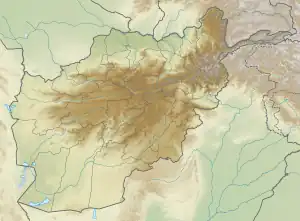

Mes Aynak Mes Aynak  Mes Aynak Mes Aynak (Hindu-Kush)  Mes Aynak Mes Aynak (Afghanistan) | |

| Coordinates: 34°24′N 69°22′E / 34.400°N 69.367°E | |

| Country | Afghanistan |

| Province | Logar Province |

| District | Mohammad Agha District |

| Elevation | 2,120 m (6,958 ft) |

Mes Aynak (Pashto/Persian: مس عينک, meaning "little source of copper"), also called Mis Ainak or Mis-e-Ainak, was a major Buddhist settlement 40 km (25 mi) southeast of Kabul, Afghanistan, located in a barren region of Logar Province. The site is also the location of Afghanistan's largest copper deposit.

The site of Mes Aynak possesses a vast 40 ha (100 acres) complex of Buddhist monasteries, homes, over 400 Buddha statues, stupas and market areas. The site contains artifacts recovered from the Bronze Age, and some of the artifacts recovered have dated back over 3000 years. The wealth of Mes Aynak's residents has been well represented in the site's far-reaching size and well-guarded perimeter. Archaeologists are only beginning to find remnants of an older 5,000-year-old Bronze Age site beneath the Buddhist level, including an ancient copper smelter.

Afghanistan's eagerness to unearth the copper below the site is leading to the site's destruction rather than its preservation. Archaeologists have photographed the site and the relics have been excavated.[1]

Etymology

The word Mes Aynak (مس عينک) literally means "little source of copper"; mis (مس) is "copper", while aynak (عينک) is a diminutive form of ayn (عين), which means "source".

History

As its name suggests, the presence of copper at Mes Aynak has been known about for some time, while the site's archaeological wealth had been discovered by Russian and Afghan geologists in 1973–4.[2]

Mes Aynak was at the peak of its prosperity between the 5th and 7th centuries AD. Coins of the Alchon Hun rulers Khingila and Mehama were found here, which confirms the Alchon presence in this area around 450-500 CE.[3]

A period of slow decline began in the 8th Century, and the settlement was finally abandoned 200 years later.[4]

On 17 May 2020, the Taliban attacked a security checkpoint near the Mes Aynak mine. Eight security guards were killed and five others were wounded.[5][6]

Mining lease

In November 2007, a 30-year lease was granted for the copper mine to the China Metallurgical Group (MCC) for US$3 billion, making it the biggest foreign investment and private business venture in Afghanistan's history.[7][8] Allegations have persisted that the then-minister of mines obstructed the contracting process and accepted a large bribe to eliminate the other companies involved in the bid.

The Afghan Mining Ministry estimates that the mine holds some six million tons of copper (5.52 million metric tons). The mine is expected to be worth tens of billions of dollars, and to generate jobs and economic activity for the country, but threatens the site's archaeological remains.[9][10] The site is accessed via a 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) motorable track from the surfaced road between Kabul and Gardez.[11] The mining lease holders propose to build a railway to serve the copper mine.[12]

As of July 2012, MCC has not developed an environmental impact plan, and has remained secretive about feasibility studies, and the plan regarding the opening and closing of the mine, as well as any guarantees contained in the contract.[13] International experts have warned that the project, and other similar projects in Afghanistan, could be threatened because MCC has not fulfilled promises made to the Afghan government, such as the lack of provision of proper housing for relocated villagers. Other investments that have yet to be fulfilled include a railway, a 400-megawatt power plant and a coal mine.[14] A report by Global Witness, an independent advocacy group that focuses on natural resource exploitation, said there was a "major gap" between the government's promises of transparency and its follow-through.[14][15]

Archaeological work

Archaeologists believe that Mes Aynak is a major historical heritage site. It has been called "one of the most important points along the Silk Road" by French archaeologist, Philippe Marquis.[16] There are thought to be 19 separate archaeological sites in the valley including two small forts, a citadel, four fortified monasteries, several Buddhist stupas and a Zoroastrian fire temple, as well as ancient copper workings, smelting workshops, a mint, and miners habitations.[4] In addition to the Buddhist monasteries and other structures from the Buddhist era that have already been identified, Mes Aynak also holds the remains of prior civilizations likely going back as far as the 3rd century BC. Historians are particularly excited by the prospect of learning more about the early science of metallurgy and mining by exploring this site. It is known to contain coins, glass, and the tools for making these, going back thousands of years.

All of this historical material is in imminent danger of destruction by the mining endeavor. In response to negative reports in the press comparing the Chinese mining company to those who destroyed the Buddhas of Bamiyan, a plan for minimal archaeological excavation was put in place. This plan still foresees the destruction of the site and everything still buried beneath it, but it does allow for the removal of whatever artifacts can be carried away by a small archaeological team led by DAFA, the French archaeological mission to Afghanistan.

Rescue excavations

Between May 2010 and July 2011 archaeologists excavated approximately 400 items; more than what the National Museum of Afghanistan housed before the war. The site covers roughly 400,000 square metres (4,300,000 sq ft), encompassing several separate monasteries and a commercial area. It appears that Buddhists who began settling the area almost two millennia ago were drawn by the availability of copper.[17] More recently, a stone statue, or stele, found in 2010 has been identified as a depiction of Prince Siddhartha before he founded Buddhism and has been taken to support the idea that there was an ancient monastic cult dedicated to Siddhartha's pre-enlightenment life.[18]

In June 2012, a conference of experts in the fields of geology, mining engineering, archaeology, history and economic development met at SAIS in Washington, D.C to assess the situation in Mes Aynak. The provisional findings were tentatively encouraging: because of the length of time before mining can actually start at the site (approximately five years), it is indeed possible for collaboration between archaeologists and mining engineers to work to save Mes Aynak's cultural treasures. The site could either become a positive model for mineral extraction working to preserve cultural heritage or become an irreparable failure. However, a number of measures, that are not currently in place, must be met first. The site is still scheduled for destruction in January 2013.[19][20]

Excavators at Mes Aynak have been denounced as "promoting Buddhism" and threatened by the Taliban and many of the Afghan excavators who are working for purely financial reasons don't feel any connection to the Buddhist artifacts.[21]

Recent developments

The U.S. Embassy in Kabul has provided a million dollars of U.S. military funding to help save the Buddhist ruins.[22] As of June 2013 there is an international team of 67 archaeologists on site, including French, English, Afghans and Tajiks. There are also approximately 550 local labourers, which is set to increase to 650 in the summer. When this occurs Mes Aynak will become "the largest rescue dig anywhere in the world".[4] All these personnel are protected by 200 armed guards. The team are using ground-penetrating radar, georectified photography and aerial 3D images to produce a comprehensive digital map of the ruins.[4]

The rescue work was continuing as of June 2014, in spite of difficulties.[23] There were only 10 international experts working at the site, and fewer than 20 Afghan archaeologists from Kabul's Institute of Archaeology. A team of seven Tajik archaeologists was also helping. Marek Lemiesz, a senior archaeologist at the site, said that more help was needed. Security was also a concern.[24]

There were also indications that mining plans were being delayed because of the declining copper prices.

Site overview-archaeological excavation gallery

Mes Aynak Stupa

Mes Aynak Stupa Mes Aynak monastery overview

Mes Aynak monastery overview Mes Aynak monastery overview

Mes Aynak monastery overview Mes Aynak monastery structure

Mes Aynak monastery structure Mes Aynak north overview

Mes Aynak north overview Mes Aynak monastery structure

Mes Aynak monastery structure Mes Aynak overview

Mes Aynak overview Mes Aynak hill top excavation

Mes Aynak hill top excavation Mes Aynak hill top excavation 2

Mes Aynak hill top excavation 2 Mes Aynak overview East hill

Mes Aynak overview East hill Mes Aynak hill top excavation workers

Mes Aynak hill top excavation workers Mes Aynak overview East 2

Mes Aynak overview East 2

Artefacts

Drachm, Vahram IV, Silver, Mes Aynak, 388–399 CE.

Drachm, Vahram IV, Silver, Mes Aynak, 388–399 CE.

Head of a donator, polychromed stucco, Mes Aynak, 3rd-6th century CE

Head of a donator, polychromed stucco, Mes Aynak, 3rd-6th century CE King and his warriors, relief, Mes Aynak, 3rd-6th century CE

King and his warriors, relief, Mes Aynak, 3rd-6th century CE Statue of bodhisattva Śäkyamuni, Schist. Mes Aynak, 3rd-5th century CE

Statue of bodhisattva Śäkyamuni, Schist. Mes Aynak, 3rd-5th century CE

Paintings

Mes Aynak Buddha painting

Mes Aynak Buddha painting Photography of wall painting

Photography of wall painting

Documentary

A documentary titled Saving Mes Aynak,[25] directed by Brent E. Huffman, tells the story of the archaeological site, as well as the dangerous environment the mine has created for archaeologists, Chinese workers, and local Afghans. The film follows several main characters, including Philippe Marquis, a French archaeologist leading emergency conservation efforts; Abdul Qadeer Temore, an Afghan archaeologist at the Afghan National Institute of Archaeology; Liu Wenming, a manager for the China Metallurgical Group Corporation; and Laura Tedesco, an American archaeologist working for the U.S. State Department.

In July 2014 it was announced that Saving Mes Aynak will be completed by the end of 2014, and is being made with Kartemquin Films.[26]

The documentary Saving Mes Aynak premiered at the 2014 IDFA film festival in Amsterdam and in the US at the 2015 Full Frame Documentary Film Festival.

In April 2015, Brent E. Huffman announced a plan to raise awareness of Mes Aynak through a #SaveMesAynak Global Screening Day and a fundraising campaign.[27]

In June 2015, the film was offered for free streaming within Afghanistan.[28]

See also

- Mundigak — archaeological site in Kandahar Province

- Hadda — archaeological site in Nangarhar Province

- Surkh Kotal — archaeological site in Baghlan Province

- Mehrgarh — archaeological site in Bolan

- Sheri Khan Tarakai — archaeological site in Bannu

- Kharwar District

- Buddhism in Afghanistan

References

- ↑ "Rescuing Mes Aynak - Photo Gallery". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Aynak Information Package, Afghanistan Geological Survey and the British Geological Survey, 2005

- ↑ Alram, Michael (2014). "From the Sasanians to the Huns New Numismatic Evidence from the Hindu Kush". The Numismatic Chronicle. 174: 274. JSTOR 44710198.

- 1 2 3 4 Dalrymple, William (31 May 2013) Mes Aynak: Afghanistan's Buddhist buried treasure faces destruction guardian.co.uk

- ↑ "Insurgents kill guards of Logar copper mine". 17 May 2020 – via http://www.menafn.com/.

{{cite web}}: External link in|via= - ↑ "Militants attacks kill 8 Afghan security personnel in Logar province". 17 May 2020. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020 – via http://www.xinhuanet.com/.

{{cite web}}: External link in|via= - ↑ Bailey, Martin (April 2010) Race to save Buddhist relics in former Bin Laden camp Archived 28 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine theartnewspaper.com

- ↑ Trakimavicius, Lukas (22 March 2021). "Is China really eyeing Afghanistan's mineral resources?". Energy Post. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ↑ Vogt, Heidi (14 November 2010) Chinese Copper Mine In Afghanistan Threatens 2,600-Year-Old Buddhist Monastery The Huffington Post

- ↑ Huffman, Brent (17 May 2012)Are Chinese Miners Destroying a 2,000-Year-Old Buddhist Site in Afghanistan? http://asiasociety.org

- ↑ "Aynak Information Package Part I Introduction" (PDF). Afghanistan Geological Survey and the British Geological Survey. 2005.

- ↑ "Agreement signed for north-south corridor". Railway Gazette International. 23 September 2010.

- ↑ Benard, Dr Cheryl (4 July 2012) Afghanistan’s Mineral Wealth Could Be a Bonanza—or Lead to Disaster thedailybeast.com

- 1 2 Nissenbaum, Dion (14 June 2012) Afghanistan mining wealth thwarted by delays The Australian, theaustralian.com

- ↑ (24 April 2012)Future of Afghan mining sector threatened by weak contracts

- ↑ "Ancient treasures on shaky ground as Chinese miners woo Kabul". 15 November 2010.

- ↑ Baker, Aryn (17 November 2011), "Deciding Between Heritage and Hard Cash in Afghanistan", Time, retrieved 20 August 2012

- ↑ Jarus, Owen (6 June 2012) Ancient Statue Reveals Prince Who Would Become Buddha livescience.com

- ↑ Experts Show How to Preserve Ancient Mes Aynak Ruins While Safely Mining Copper Near Kabul, Afghanistan Archived 29 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine ARCH International, archinternational.org

- ↑ Huffman, Brent (24 September 2012). "Ancient site needs saving not destroying". CNN. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Bloch, Hannah (September 2015). "Mega Copper Deal in Afghanistan Fuels Rush to Save Ancient Treasures". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015.

- ↑ Global Heritage Fund blog article (July 2012) GHF Supports Buddhas of Aynak Documentary Archived 26 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Bloch, Hannah. "Rescuing Mes Aynak". Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ 24 June 2014, Saving Buddhist statues: Afghanistan’s big dig america.aljazeera.com

- ↑ Ward, Olivia (14 December 2012). "Afghanistan archeological site in a race for survival". Toronto Star. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ "Saving Mes Aynak comes to Kartemquin". Kartemquin Films. 1 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ↑ "Filmmakers Launch 'Saving Mes Aynak' Campaign for Afghan Archaeological Site". Variety. 26 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Corey, Joe (25 June 2015). "Saving Mes Aynak is free to watch in Afghanistan". Inside Pulse. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

Kartemquin Films announced today that they will make director Brent E. Huffman's film Saving Mes Aynak available for free to the people of Afghanistan.

Further reading

- Lerner, Judith A. (2018). "A prolegomenon to the study of pottery stamps from Mes Aynak". Afghanistan. 1 (2): 239–256. doi:10.3366/afg.2018.0016. S2CID 194927542.