Regency of Algiers | |

|---|---|

| 1516–1830 | |

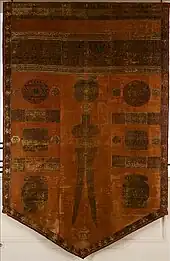

Coat of arms of Algiers

(1516–1830) | |

| Motto: الجزائر المحروسة Algiers the well-guarded[3] | |

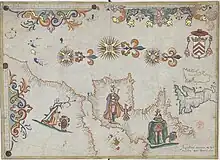

Overall territorial extent of the Regency of Algiers in the late 17th to 19th centuries[5] | |

| Status | State affiliated to the Ottoman Empire (Nominal since 1659)[6] |

| Capital | Algiers |

| Official languages | Arabic and Ottoman Turkish |

| Common languages | Algerian Arabic Berber Sabir (used in trade) |

| Religion | Official, and majority: Sunni Islam (Maliki and Hanafi) Minorities: Ibadi Islam Shia Islam Judaism Christianity |

| Demonym(s) | Algerian or Algerine |

| Government | 1516–1519: Sultanate 1519–1659: Viceroyalty 1659–1830: Stratocracy[7][8] (Political status) |

| Pasha | |

• 1516–1518 | Oruç Reis |

• 1710–1718 | Baba Ali Chaouch |

• 1818–1830 | Hussein Dey |

| Historical era | Early modern period |

| 1509 | |

| 1516 | |

| 1521–1791 | |

| 1541 | |

| 1550–1795 | |

| 1580–1640 | |

| 1627 | |

| 1659 | |

| 1681–1688 | |

| 1699–1702 | |

| 1775–1785 | |

| 1785–1816 | |

| 1830 | |

| Population | |

• 1830 | 3,000,000–5,000,000 |

| Currency | Major coins: mahboub (sultani) budju aspre Minor coins: saïme pataque-chique |

| Today part of | Algeria |

| History of Algeria |

|---|

The Regency of Algiers[lower-roman 1] (Arabic: دولة الجزائر, romanized: Dawlat al-Jaza'ir) was an autonomous eyalet of the Ottoman Empire in North Africa from 1516 to 1830. It was an early modern tributary state founded by the corsair brothers Oruç and Hayreddin Barbarossa, ruled first by viceroys, which later became a sovereign military republic.[lower-roman 2] The Regency was the earliest and most powerful of the Barbary states with the largest navy in North Africa. Situated between the Regency of Tunis in the east, the Sharifian Sultanate of Morocco and Spanish Oran (until 1791) in the west, the Regency originally extended its borders from the Mellegue river in the east to Moulouya river in the west and from Collo to Ouargla, with nominal authority over the Tuat and In Salah to the south. At the end of the Regency, it extended to the present eastern and western borders of Algeria.

The sixteenth century witnessed the clash between the Spanish and Ottoman empires in the Mediterranean and the rise of the Algerian regency in North Africa. When the war between the two empires ended in the early 17th century, Algiers refused to recognize peace. So France, England and the United Kingdom of the Netherlands were embarrassed as their merchant ships and goods were captured and their subjects enslaved. The sultan could not force his vassals to cease their attacks. European powers then had to deal directly with the regency after a century of negotiations and wild sea operations, but by then the pirates had expanded across the Atlantic and the Barbary slave trade reached its apex in Algiers. Meanwhile, its growing autonomy culminated in the Janissary coup in 1659, with rulers emerging and being elected locally.

After successive wars with France, Maghrebi states and Spain in 18th century, linked to the consolidation of territorial soveregnity, diplomatic relations with European states and the regency's attempt to better fit into Mediterranean trade, Algerian privateering, also known as the "Corso", experienced serious bursts with the contraction exchanges during the European wars of the French Revolution and Empire, when Algerian merchant ships were excluded from European ports. This caused the Barbary wars in which the balance between the two shores of the Mediterranean maintaining the permanence of the corso, broke at the beginning of the 19th century. European states acted together in the Anglo-Dutch expedition in 1816 under Lord Exmouth, marking a decisive turning point and practically putting an end to the corso. Internally, central authority weakened due to economical difficulties due to the decline of the corso, this would prompt violent tribal revolts, led mainly by maraboutic orders such as the Darqawis and Tijanis.

France took advantage of this situation to intervene, and invaded in 1830, leading to the French conquest of Algeria and eventually French colonial rule until 1962.

History

Central Maghreb in early 16th century

After the Emirate of Granada fell in 1492, Spanish imperialism manifested through domination of the cities of the Maghreb by establishing "Presidios". Conquered ports that were transformed into strongpoints filled with garrisons and surrounded by formidable walls.[18] This allowed the Spaniards to control waystations for caravans from western Sudan, Tripoli and Tunis in the east and Ceuta and Melilla in the west, passing through Bejaia, Algiers, Oran and Tlemcen. Control over this trade and its two main commodities, gold and slaves, became essential for the Spanish treasury.[19] The loss of the middle Maghreb's role as a mediator of commerce between Europe and Africa - especially in gold - led to economic stagnation, decline in trading resources, and deterioration of craftsmanship in its two historical capitals, Bejaia and Tlemcen. The country subsequently entered a state of political fragmentation and weak centralization, exacerbated by the Iberian trade monopoly on its capacity to collect taxes and the activities of its merchant class.[20]

The Maghreb became vulnerable to incursions from the north shore of the Mediterranean. Within two decades, the Spanish Empire captured multiple important cities and ports along the shores of the Maghreb. The first along the Moroccan coastline to fall was Melilla in 1497,[21] followed by the Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera in 1508. Along the Algerian shores, the city of Mers El Kébir fell in 1505, followed in 1509 by Oran - the most important sea port directly linked to Tlemcen, capital of the Zayyanid Kingdom.[22] Bejaia in eastern Algeria and Tripoli in Libya were taken in 1510. Other coastal cities such as Algiers and Tunis chose to submit to Spanish sovereignty through humiliating agreements.[23]

Establishment

Barbarossa brothers arrive in 1512

Beginning in 1512, Ottoman privateer brothers Oruç and Hayreddin—both known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or "Red Beard", operated successfully off Tunisia under the Hafsids and became famous for victories against Spanish naval vessels at sea and on the shores of Andalusia. That year scholars and notables of Bejaia contacted them, asking their help in dislodging the Spaniards from Bejaia. However, their attempt to do so failed due to the city's formidable fortifications. Oruç was wounded while trying to storm the city, and his arm had to be amputated.[24] He realized that his forces' position in the valley of La Goulette hampered their efforts against the Spaniards and moved them to Jijel, a center of trade between Africa and Italy, occupied since 1260 by the Genoese, where he received pleas for help from its inhabitants. Oruç took the city in 1514, establishing a base of operations there, and its inhabitants pledged allegiance to him as their prince,[25] as did the Emir of Kuku Ahmed Belkadi.[26] He urged Oruç to attack the Spaniards again in Bejaia, so he launched another assault in 1514, besieging the city for nearly three months, ultimately to no avail. Oruç made a third attempt in the spring of the following year with a large force. But he withdrew when his ammunition ran out and the Hafsid emir refused to provide more. Though he succeeded in capturing hundreds of Spanish prisoners.[27]

Capture of Algiers in 1516

The occupation of Bougie and the takeover of Oran by Pedro Navarro and Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros alerted the Algerian population to the imminent threat, and unable to resist the Spanish, they agreed to submit and recognize the Catholic King Ferdinand II of Aragon as their sovereign, pay a yearly tribute, release Christian prisoners, forsake piracy, and prevent the enemies of Spain from entering their harbor. A delegation of significant individuals escorted shaikh Salim al-Tumi of the Thaaliba to Spain, where he swore an oath of allegiance and presented gifts to Ferdinand. To ensure the fulfillment of the piracy requirements and to observe the residents of Algiers,[28] Pedro Navarro captured the island of Peñon, within artillery range of the city, and built a fort there, garrisoned with 200 men. The Algerians sought to break free of the Spanish and took advantage of the excitement over the death of King Ferdinand to seek help from Oruç and his men.[25]

New masters of Algiers

A delegation to Jijel in 1516 complained to Oruç of the constant distress and danger they faced. He had planned a final offensive against Bejaia, but abandoned his plans to help the citizens of Algiers. Oruç set out at the head of a land force of 5,000 Kabyles and 1,500 Turks, followed by 800 arquebusiers, while Hayreddin led a naval fleet of 16 galliots. They rendezvoused in Algiers,[29] whose population celebrated their arrival and hailed them as heroes.[30] Hayreddin launched a naval bombardment of the Spanish fort, and Oruç took Cherchell, where he eliminated another Ottoman captain named Qara Hassan who had been cooperating with some Andalusian immigrants.[25] Oruç did not possess the means to recover the Peñon of Algiers immediately, and as his presence often undermined al-Tumi's own authority, the latter eventually sought the help of the Spaniards to drive him out. In response, Oruc assassinated him.[31] He proclaimed himself "Sultan of Algiers", and raised his banners in green, yellow, and red above the forts of the city.[32] The Spaniards reacted by sending governor of Oran Diego de Vera against Algiers in late September 1516. Oruç allowed his forces to land then moved against them, taking advantage of their retreat and northern wind to drown, kill, and capture many prisoners, in a total defeat for the Spaniards, and a momentous victory for Oruç,[33] which expanded his influence further in the Algerian heartland.[34]

Campaign of Tlemcen in 1518

Oruç decided to take action against the Prince of Ténès and Spanish vassal Hamid bin Abid by seizing his city, where he vanquished the enemy army at the Battle of Oued Djer in June 1517, killed the prince and expelled the Spaniards stationed there. He then divided his newfound kingdom into two parts: An eastern part based out of Dellys to be ruled by his brother Hayreddin, and a western part centered on the city of Algiers to be ruled by him personally.[35] While Oruç was in Ténès, a delegation from the city of Tlemcen came to him to complain about the poor conditions in their country and the growing threat of a Spanish occupation of their city, exacerbated by squabbling between the Zayyanid princes over the throne.[25] Abu Ahmed III had seized the throne in Tlemcen by force after he expelled his nephew, Abu Zian III, and put him in prison. Oruç elected to fulfill the wishes of the delegation, and appointed his brother Hayreddin as a ruler over the city of Algiers and its surroundings.[36]

Death of Oruç Barbarossa

Oruç marched towards Tlemcen, capturing the castle of Banu Rashid along the way, and garrisoning it with a large force led by his brother Isaac in order to protect his rear. Oruç, along with his troops, entered the city and removed Abu Zayan from prison, restoring him to his throne, before progressing westward along the Moulouya to bring the Beni Amer and Beni Snassen tribes under his authority.[37] Abu Zayan began to conspire against Oruç who arrested and executed him. Meanwhile, the deposed Abu Ahmed III fled to Oran to beg for help from his former enemies - the Spaniards - to retake his throne. The Spaniards chose to answer his pleas, capturing the Banu Rashid castle and killing Isaac in late January 1519, then layed siege on Tlmecen. Oruç locked himself inside the Mechouar palace for several days to avoid a hostile populace which eventually opened the gates for the Spanish troops.[37] Oruç attempted to flee Tlemcen, but the Spaniards pursued and killed him along with his Ottoman companions. His head was then sent to Spain, where it was paraded across its cities and those of Europe. His robes were also sent to the Church of St. Jerome in Cordoba, where they were kept as a trophy.[38]

Algiers joins the Ottoman Empire (1519-1533)

Hayreddin was proclaimed Sultan of Algiers in late 1519.[39] Following a disastrous attempt by the Spanish Empire to take Algiers in 1519 led by Hugo of Moncada,[40] a rebellion attempt in Algiers and the reversal of his alliance with the Kingdom of Kuku after the death of its ruler, Ahmed Belkadi the elder, along with the deterioration of various forms of support on the internal level and growing Hafsid hostility in Tunis, Hayreddin became increasingly aware of the necessity of external Ottoman support to maintain his possessions around Algiers.[41] Thus, an assembly made up of Algerian notables and ulemas led a delegation to present to the Ottoman Sultan Selim I a proposal to attach Algiers to the Ottoman Empire.[42]

The delegation was tasked with making the strategic importance of Algiers in the Western Mediterranean understood to the Ottoman Sultan. The proposal was not initially welcomed with enthusiasm by Constantinople, which found the idea of integrating a territory so distant and so close to Spain perilous and was only definitively accepted under Suleiman in 1521.[43] Hayreddin Barbarossa was named Beylerbey.[39] The important role of the regency fleet in the Ottoman maritime campaigns and this voluntary membership gave a particular character to the relations between Algiers and Constantinople. The regency was considered not a simple province but an Imperial Estate.[42] This state was very important in the eyes of the Ottomans, because it was the spearhead of Ottoman power in the western Mediterranean.[44]

Hayreddin's reconquest of Algiers

After the defeat at Issers against the joined Kuku-Hafsid forces then the capture of Algiers in 1520, the Kabyles of Kuku began a five to seven years period of rule under Sultan Belkadi over Algiers (1520-1525/1527).[45] Hayreddin retreated to Jijel in 1521, from whence he allied himself with the Kabyles of Beni Abbas, rivals of Kuku.[46] Hayreddin continued his progress in the east: taking Collo in 1521, Annaba and Constantine in 1523, then with the support of the Beni Abbès, crossed their stronghold of the Babors and the Soummam River. The Djurdjura was crossed without incident, but at Iflissen they had to face a detachment of Belkadi, which they defeated. Belkadi then withdrew to Tizi Naït Aicha (Thénia) to block the main access roads to Algiers. Hayreddin detoured to enter the Mitidja plain. Before the battle, Belkadi was killed by one of his soldiers, and so the debacle caused by the assassination opened the way to Algiers, where the population, which had complained about Belkadi opened the doors to Hayreddin in 1525 or 1527.[47]

But Algiers was still threatened by the Spaniards on the Peñon, from which they controlled the port. Hayreddin summoned the Spanish commander, Don Martin de Vargas, to surrender with his garrison of two hundred soldiers. With this ultimatum rejected, he attacked and bombarded the Peñon and captured it on May 27, 1529.[48] With the materials salvaged, the island was attached to the land; Thus the harbor was enlarged to what would become a major Port and headquarters of the Algerian corsair fleet.[49] The capture of the Peñon had a huge impact in Europe and Africa. The Ottomans were firmly established in Algiers; A new destiny was about to open up in the central Maghreb, a new state to be founded there.[48]

The Morisco rescue missions

After he successfully repelled Andrea Doria's Genoese landing on Cherchell in 1531,[50] Barbarossa sent ships to help the Moriscos to flee the Spanish inquisition. Hayreddin's ships transported to the shores of Algiers about 70,000 of them.[51] Often, the number of ships was not sufficient to carry all the refugees, so the garrison was forced to land on the enemy's coast, leaving its place to the immigrants and remaining there as a guard for the ones left behind. In Algiers they settled at the top of the city from the suburb close to the Kasbah Palace in Algiers, which is the area known today as the "Tagarin", while others settled in Algerian cities east and west, where they built - as Leo Africanus said: "2,000 houses, and among them were those who settled in Morocco and Tunisia. the Maghreb people learned much of their craft, imitated their luxury, and rejoiced in them".[51]

Now that Barbarossa has established the military basis of the regency,[52] he was called in 1533 by the Sultan to exercise the function of Kapudan Pasha, he left Hasan Agha in command as his deputy when he had to leave for Constantinople in 1533.[53]

Hayreddin's successors

War with Spain for the Zayyanid Kingdom

Two years later in 1535, Charles V of Spain conquered Tunis against the troops of Hayreddin Barbarossa. In October 1541, a massive Imperial expedition was led by the emperor himself this time against Algiers to put an end to the Barbary pirates who were spreading terror in the western Mediterranean, ending in a total disaster for the Christian army.[54][55]

.jpg.webp)

Successive expeditions set out to try to gain control of the city of Mostaganem. A first expedition was carried out in 1543, then a second one In 1547, in which Martín Alonso Fernández, Count of Alcaudete and his son Alonso de Córdoba were defeated due to poor campaign planning, a shortage of ammunition, and a lack of experience and discipline among the Spanish troops.[56][57]

In 1544, Hasan Pasha, Hayreddin's son, became the first governor of the Regency of Algiers to be directly appointed by the Ottoman Sultan, according to Diego de Haëdo, he took the title of beylerbey through a demand by Hayreddin Barbarossa to the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.[58] In 1551, Hasan Pasha defeated the Spanish-Moroccan armies during a campaign to recapture Tlemcen, thus cementing Ottoman control in western and central Algeria.[59] After that, the conquest of Algeria sped up. In 1552 Salah Rais, with the help of some Kabyle kingdoms, conquered Touggourt, and established a foothold in the Sahara.[60] A year later, Salah Raïs expelled the Portuguese from the penon of Valez before leaving a garrison there.[61]

In 1555, the Regency of Algiers managed to score a decisive victory against the Spanish empire in Bougie and another in Mostaganem three years later, thus cementing Ottoman control in North Africa for good. During the 16th, 17th, and early 18th century, the Kabyle Kingdoms of Kuku and Ait Abbas managed to maintain their independence[62][63] repelling Ottoman attacks several times, notably in the First Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbes then in the Battle of Oued-el-Lhâm.

Ottoman dominance in the Maghreb

Algiers became a base in the war against Spain and also in the Ottoman conflicts with Morocco. In the west, the Algerian-Sharifian conflicts shaped the western border of Algeria.[64] There were numerous battles between the Regency of Algiers and the Sharifian Saadi dynasty in Morocco. For example: The campaign of Tlemcen in 1551 and the campaign of Tlemcen in 1557, in which the independent Kabylian Kingdoms had significant involvement. The Kingdom of Beni Abbes participated in the campaign of Tlemcen in 1551 and the Kingdom of Kuku also participated in the Battle of Taza (1553) and the capture of Fez in 1554 in which Salih Raïs defeated the Moroccan army and conquered Morocco up until Fez, placing Ali Abu Hassun as the ruler and vassal to the Ottoman sultan.[65][66] In October 1557, a Ottoman army was sent to Tuat against Mohammed al-Shaykh, the Saadi ruler of Morocco at the time, in order to lift the blockade imposed by his troops, decisively defeating his army and lifting the siege off the region.[67] This was followed by a failed attempt to take Oran in 1563.[68]

After the failed Ottoman siege of Malta in 1565 and the revolt of the Moriscos in 1568, the Beylerbey of Algiers, Uluç Ali, set off over land toward Tunis with 5300 Turks and 6000 Kabyle cavalry.[69] Uluç Ali defeated the Hafsid Sultan at Béja, and conquered Tunis without suffering great losses. He then brilliantly led Algerian corsairs on the left wing of the Ottoman fleet in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, where he managed to vainquish the Christian right wing led by Giovanni andrea doria and his Maltese Knights before saving what remained of the defeated Ottoman navy.[70] Meanwhile, Mulay Ahmad III was forced to take refuge in the Spanish presidio of La Goleta in the bay of Tunis. The Christian forces were able to recover Tunis in 1573. However, the Ottoman forces under Uluç Ali conquered Tunis yet again in 1574.[71]

The capture of Fez in 1576 resulted in Abd al-Malik being installed as an Ottoman vassal ruler over the Saadi dynasty by Caïd Ramazan pasha of Algiers.[72][73] In 1578 an army corps of the Regency was sent to help the inhabitants of Tuat once again against the Saadis and allied tribes from Tafilalt, sending "a written warning to the assailants".[67][74] In the same year, Spain would send an embassy to Constantinople in 1578 to negotiate a truce, leading to a formal peace in August 1580 since the Regency of Algiers was a formal Ottoman territory at that time, rather than just a military base in the war against Spain.[53]

Relations with Ottoman Empire worsen

After the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, the Ottoman hold over Algiers weakened; The Pasha, representative of Isbanbul, did not in fact have full authority,[75] over time, the corsair captains, commonly known as "Raïs", and Janissaries who made up the "Odjak", acted only according to their interests as Imperial fleets left the waters for intense piracy.[76] In the early 17th century, European nations signed peace treaties that ended hostilities with the Ottoman Empire, including Austria (1606) and the Netherlands (1612). Before that, France and Great Britain concluded so-called Capitulations treaties with the Ottoman Empire in 1536 and 1579 respectively. These capitulations gave extraterritorial rights to foreigners living in the Ottoman Empire. They were originally intended to encourage trade. But Algiers disapproved of Constantinople's foreign policy, which it believed gave too many privileges to foreigners.[77]

Ottoman Capitulations to France

The Janissaries who were stationed in and paid by Algiers, started to disregard the sultan's orders. They decided sovereignly on war operations through their military council, also known as "Diwan", taking into account neither the capidji (Imperial envoy) sent by the sultan nor the alliances concluded by Istanbul.[78] The Sublime Porte renewed the treaty in 1604 giving even more privileges to France in total ignorance of Algerian interests. Clause 14 of the treaty, authorized the French King to use force against Algiers in case the treaty was not respected. This prompted Khider Pasha of Algiers to attack a French trade center in eastern Algeria known as the Bastion of France, the pasha himself seized 6,000 sequins which the sultan Ahmed l had sent to French merchants to compensate them for losses caused by the raid on the Bastion, an act for which the Sultan ordered Khider pasha hanged up. Still the French could not rebuild this Bastion; the Diwan of the Janissaries opposed it and decreed that whoever undertook it would be punished by death.[79] The Diwan even refused to receive the French envoy accompanied by a representative of the sultan, indicating that relations with France were seen in a diverging way by Algiers and by Istanbul.[78]

Ali Bitchin Raïs

a%252C_li_7_agosto_1638_-_btv1b531945942_(2_of_3).jpg.webp)

The Raïs, who formerly responded to the sultan's slightest appeal, would soon discuss his orders. They began by demanding compensation when they were asked for a ship; they even demanded that any indemnity be paid in advance. In 1638, they felt they had been betrayed by Istanbul. They had been called by the sultan Murad IV to fight Venice, but a storm having forced them to take shelter in a port, the Venetians attacked them there and destroyed part of their fleet in Valona. The sultan refused to compensate the corsairs for their losses. Then, Venice having bribed the vizier, peace was made to the great anger of Algerian corsairs.[80][81]

A raïs, Ali Bitchin, head of the tai'fa (community of Corsair captains) from 1630 to 1646, became, at that time, the main character in Algiers.[82] Admiral of all the galleys, head of the corporation of corsairs, he was immensely rich: having two palaces in Algiers, a mosque built by himself, nearly 500 slaves in his private prisons, and married to a daughter of the King of Kuku, Ali Bitchin wanted to pursue an independent policy, as he refused to answer positively to sultan Ibrahim IV's request to join the Cretan war.[83] Fearing to see an autonomous power assert itself, the sultan wanted to arrest Ali Bitchin, but the population rose up and the Pasha of Algiers was arrested. The Diwan of the militia had tolerated Ali Bitchin's insubordination, but in return demanded that he pay the Janissaries' salaries. Ali Bitchin took refuge in Kabylia, stayed there for nearly a year, then returned in force to Algiers. He reigned there as a true master, claimed the official title of pasha and claimed from the sultan Mehmed IV, in 1649, 60,000 golden soltanis for the dispatch of 16 galleys. The sultan then appointed another pasha, and when the latter arrived, Ali Bitchin died suddenly, possibly poisoned.[82][83]

Foreign policy

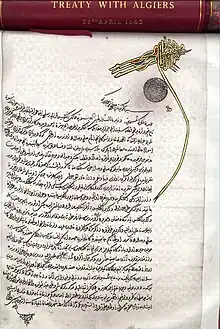

In light of Algiers refusing to abide by the Capitualtions treaties bounding the Sublime Porte with European states in the 17th century, Europe negotiated with Algiers through its admirals. Treaties would be concluded about commerce, tribute payment and redemption of slaves.[84] Algerian relations with European powers were based on averting any coalition that could pose a serious threat to it. Therefore It played off adversaries that could have outmatched the Regency in case they united against it.[85] Very cleverly, the Deys of Algiers tried to deal with each country separately, while negotiating with the French to better attack the English or the Dutch, and vice versa,[86] giving a fine example of how useful this technique could be in the international relations of states.[lower-roman 3]

And so Algiers was declaring war against every country with which it did not conclude treaties, foremost of which was Spain. When a European nation was at war with Algiers, it almost inevitably meant that its shipping could not compete with other shipping in the region whose the home nation was at peace with the North African Regency.[88] In fact only ships from European countries that were at peace with Algiers could expand the handling of merchant shipping in the Mediterranean, now called cabotage.[89] European vessels carried Passports issued by their diplomatic mission in Algiers to protect them from Algerian cruisers and also to resolve disputes over prizes.[84]

Kingdom of France

In 1604, Khider Pasha attacked the Bastion of France in clear defiance to the Ottoman capitulations to France; King Henry IV envoy came to Algiers accompanied by a capidji from the Porte with a firman from the sultan Ahmed I ordering the release of the French captives and the rebuilding of the Bastion, yet the Janissary Aghas revolted, their diwan refused to authorize the reconstruction of the Bastion and agreed to hand over the French captives only on condition that the Muslims detained in Marseilles were to be released.[90]

Bastion de France treaties (1619-1640)

After losing more than 900 ships and 8000 Frenchmen were reduced to slavery,[91] France decided to negotiate directly with Algiers. Negotiations began in 1617 but soon reached an impasse. Part of the trouble stemmed from the question of the return of two Algerian cannons seized by the Dutch corsair Zymen Danseker when he left the Algerian navy in 1607 and given to the Duke de Guise of Provence.[92] Two years later, a treaty was concluded in 1619,[93] then a second one in 1628,[94][95] upon which the Algerians undertook to :[96]

- Respect the French coast and vessels,

- Prohibit in their ports the sale of goods seized on French ships,

- French traders could reside safely in Algiers,

- French concessions of the Bastion were recognized and protected,

- Trade in leather and wax allowed.

Sanson Napollon, who had been appointed chief of the Bastion de France, was able to offer Marseille all the wheat it needed. In 1629 however, Marseilles had fifteen corsairs of an Algerian ship massacred, and the rest taken prisoner to France.[97] In 1637, Ali Bitchin razed the French fortress and the Diwan decided that "never the said Bastion would recover, neither by request of the King of France, nor by command of the Grand Sultan, and that the first who would speak of it would lose his head".[98] But in 1640, a new treaty restored to France its establishments in Africa, and coral fishermen obtained on their side assistance and security.[98] In exchange for paying the Pasha a sum equivalent to nearly 17,000 pounds.[99]

Kingdom of England

_-_The_%22Mary_Rose%22_Action%252C_28_December_1669_-_RCIN_405223_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

In 1621, English admiral Robert Mansell took part in an expedition during which he sent fireships (old burnt ships) against the pirate fleet moored in the bay of Algiers. This expedition was a failure and Mansell was recalled to England on May 24, 1621.[100]

James I negotiated directly in Constantinople in 1622 with the Pasha of Algiers, who happened to be visiting there.[94][101] Until 1662, no country succeeded in permanently holding the "free ship and free goods" principle from the Algerian Pirates. England introduced a series of anti-counterfeiting and mandatory 'Algerian Passports' on its southbound merchant ships, guaranteeing each ship's authenticity in case it encountered Algerian pirate vessels.[102] Faced with the subsequent strong growth of the English fleet in the Mediterranean, the Algerians broke the peace twice in the following years (1668-1671, 1677-1682) and privateered wars against the English, who reacted strongly every time. Two wars ended with mixed results for Algiers, the first of which led to a regime change in the Regency. Yet the second one witnessed Algiers forcing the English monarch Charles II to recognise his subjects as slaves in Algiers.[103] When Algiers faced dangerous French attacks in the 1680s, Algiers finally opted for a lasting peace with England that would last more than 140 years.[104]

Dutch Republic

The Dutch recognized the impact of the Anglo-Algerian peace on their own shipping activities. Various reports of Armenian merchants arriving at The Hague, from the courts of Madrid or from Messina, all indicated that goods were being transferred from the Dutch to the British.[105] Thus, from 1661 to 1663, the Republic, under the command of Michiel de Ruyter, sent without success several squadrons of warships to settle the matter and force the Algerians to accept a treaty of permanent peace.[106]

From 1679 to 1686, the Republic was able to maintain an uneasy peace with Algiers thanks to the skills of the Dutch diplomat Thomas Hees, thus securing a significant share of peaceful trade with southern Europe,[107] in return for sending cannons, gunpowder and naval stores in form of tribute, which sucited vivid condemnations from France and England.[108] Yet the peace didn't last, and between 1714 and 1720, 40 ships were made prizes and 7500 seamen were reduced to slavery.[109]

Finally, the Dutch achieved the peace they had longed for after much negociations.[109] The new Dutch consul in Algiers, Ludwig Hameken, asked for a Mediterranean pass, and agreed to pay a yearly tribute for a whole century. When Britain went to war with Spain, the Dutch managed to stay ahead of their main rivals. But after the war, the British shipping industry in the Mediterranean flourished, while the Dutch never kept up the competition.[110]

Golden Age of Algiers in 17th century

Algiers grew dominant and increasingly independent from Constantinople. Thus its corso was made easier during the 17th century's "golden age of corsairs":[111] Its port, navy, and population increased, due to a mediating status consisting of a piracy economy system of forced exchange and paid protection, ensuring the safety of crews, cargo and ships at sea.[112] As Maghreb populations became wealthy from the sale of seized ships and cargo and also from ransoms paid by European states for the release of captured prisoners on the high seas thanks to plunder,[112] their homes were built with "the most precious objects and delicacies from the European and Eastern worlds".[111] While over 25,000 slaves were held in Algiers.[113]

The Raïs rose in the ocean as soon as they had adopted the use of round vessels. Exploring the roads of India and America, they disturbed the commerce of all enemy nations. In 1616, Rais Mourad the younger plundered the coasts of Iceland, from where he brought back to Algiers 400 captives. In 1619 they ravaged Madeira. In 1631, they famously sacked Baltimore in Ireland, blocked the English Channel, and would make catches in the North Sea.[114][115]

African campaigns (1663-1688)

In 1650, the Raïs operated in the very waters of Marseilles, and ravaged Corsica; in 1651 they landed near Civitavecchia and took many prisoners in the Roman countryside. The goods taken by the Algerians were sold by the merchants of Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Genoa and Livorno, who became the corsairs' brokers. Spain was powerless, Sicily and the small islands of Italy were incapable of opposing the raïs any longer, France was engulfed in the wars of Fronde. However, the reaction of the Europeans was not long incoming: British Admiral Blake, the French Levant fleet, the Dutch with Michiel de Ruyter, and the Knights of Malta resumed their offensives against the Algerian fleet.[116] In 1658, Cardinal Mazarin even gave the order to reconnoitre the Algerian coasts with a view to a permanent installation; he and First minister of State Jean-Baptiste Colbert were advised on Bone, Jijel and Collo.[78] Large forces were sent to occupy Collo in the spring of 1663, but the expedition ended in a failure. In July 1664, King Louis XIV directed another military campaign against Jijel, which was occupied for nearly three months, but it also ended in a defeat.[117] Despite a minor victory against Algerian vessels near Cherchell in 1655, France was forced to negotiate with Algiers and sign the May 7, 1666 agreement, which stipulated the implementation of the 1628 treaty.[118][119] King Louis XIV who sought to have the French flag respected in the Mediterranean, sent several strong bombing campaigns against Algiers from 1682 to 1688 in what is known as the Franco-Algerian war.[86] After a fierce resistance led by Dey Hussein mezzomorto, a conclusive peace treaty was finally signed.[120]

Maghrebi Wars (1678-1707)

Algeria's relations with the rest of the Maghreb countries were mediocre for several historical reasons.[121] Algiers considered Tunis a dependency by virtue of the fact that it was the one that expelled the Spaniards from it and annexed it to the Ottoman Empire which made the appointment of its pashas the prerogative of the Algerian beylerbeys,[122] and on this basis Algiers was constantly trying to make this dependence a tangible reality.[123] Tunis rejected this and saw that, like Algiers, it was subordinate to Constantinople. Tunisia also had ambitions in the Constantine region inherited from the Hafsid era.[124] As for Morocco, it resisted from the beginning, and with determination, the Turks that sought to control it. It began to view Algiers as a danger hanging over it and therefore it must be avoided by all means, including conspiring with any foreign power. More than this, Morocco had ancient ambitions in western Algeria and Tlemcen in particular, and its sultans did not hide this desire. On this basis, relations between Ottoman Algeria and its neighbors were troubled most of the time.[124]

Tunisian campaigns

.svg.png.webp)

Tunis adamantly refused subordination to Algeria. Since 1590, the Diwan of Tunisian Janissaries revolted against Algiers, and the country became a vassal of Constantinople itself.[124] A peace treaty was concluded in May 17, 1628 following an Algerian victory would be devoted to the delimitation of the borders.[125] In 1675, Murad II Bey died. This unleashed a twenty years civil wars between his sons.[126] Dey Hadj Chabane would take this opportunity to lead victorious invasions in Tunis, such as the Battle of Kef, and the conquest of Tunis.[127] Fed up with this situation, the Tunisians revolted and signed an alliance with the sultan of Morocco, which would soon culminate in the Maghrebi war (1699-1701).[121]

In 1700, The Maghrebi war started. Murad III Bey of Tunis took the city of Constantine. It was not long before the regency of Algiers regained the upper hand and 7000 Tunisians were killed in the Battle of Jouami' al-Ulama.[128] Ibrahim Cherif, the Agha of the Tunisian spahi cavalry, put an end to the Muradid regime, he was named Dey by the militia and made pasha by the Ottoman sultan. However, he did not manage to put an end to the Algerian and Tripolitan incursions. Finally defeated near Kef by the Dey of Algiers on 8 July 1705, he was captured and taken to Algiers.[129]

Vassalisation of the Tunisian Regency

In 1705, Hussein I ibn Ali Bey founded the Husainid dynasty of Tunis. After a failed revolt, Abu l-Hasan Ali I Pasha took refuge in Algiers where he managed to gain the support of the Dey Ibrahim Pasha.[130] Hassan Bey of Constantine dispatched a force of 7,000 men led by Danish slave Hark Olufs to invade Tunis in 1735 and install Ali Pasha there as its Bey,[131] who recognised himself as a vassal of Algiers and paid an annual tribute to the Dey.[131][132]

Another campaign was directed against Tunis in 1756.[133] Taken prisoner by the Algerians, Ali I Pasha was deposed, brought to Algiers in chains, and was strangled by supporters of his cousin and successor Muhammad I ar-Rashid on September 22. Algiers imposed a tribute on Tunis, the latter had to send oil to light the mosques of Algiers each year. Tunis had become a tributary of Algiers and continued to pay an annual tribute and recognise Algerian suzerainty for more than 50 years.[134][135]

Moroccan campaigns

.jpg.webp)

In 1678, Moulay Ismail mounted an expedition to Tlemcen.[136] He assembled his contingents in the Upper Moulouya, joined by the tribes of Orania and advanced as far as the Chelif region to fight battle there.[137] The Turks of Algiers brought in the artillery, which terrified the auxiliary tribes of the Moroccan sovereign, who then broke away from him. thus Moulay Ismail ended up negotiating with Dey Chabane and fixing the border on the Moulouya,[138] which throughout the Saadian period, had separated the two countries. In 1691, Moulay Ismail launched a new offensive against Orania, where the Dey Chabane defeated the attackers on the Moulouya and marched on Fez.[139] Moulay Ismail reportedly prostrated to the Dey in his tent, saying: "You are the knife and I the flesh that you can cut".[140] He agreed to pay tribute and sign the treaty of Oujda which confirmed the Moulouya river as the border.[141] In 1694, the sultan of Istanbul invited that of Morocco to cease his attacks against Algiers.[137]

Moulay Ismail's Oranian debacle

In 1700, after coming to an agreement with the Tunisian Muradids who were to simultaneously attack Constantine, the Moroccan sovereign launched a new expedition against Orania with an army composed mostly of Black Guards.[142] But, Moulay Ismail's 60,000 men were beaten again in the Chelif river by the Dey Hadj Mustapha.[143][144] In the following years Moulay Ismaïl led Saharan incursions towards Ain Madhi and Laghouat without succeeding in settling there permanently.[144] Following these expeditions, the Dey of Algiers, Moustapha II then wrote to Moulay Ismaïl about the attachment of the Algerians and their territory to the power of the regency of Algiers.[145]

As the Algerian assault on Spanish Oran was imminent, Moulay Ismail made one last attempt to capture Oran in 1707. But his army was almost entirely destroyed.[146][147] The Sharfis had still been able to preserve the independence of their country, but by renouncing any project of expansion towards Orania.[148]

War with Spain in 18th century

Taking advantage of the War of the Spanish Succession, Algerian western Bey Mustapha Bouchelaghem captured the cities of Oran and Mers-el Kebir in 1708.[149] But he eventually lost the two cities to the Spanish after a successful campaign led by the Duke of Montemar in 1732.[150]

In 1775, a Spanish Expedition intended to reduce the pirates of the Mediterranean was ordered by the Irish admiral Alejandro O'Reilly. The assault was a spectacular failure and the campaign a humiliating blow to the Spanish military reorganisation.[151]

From August 1 to August 9, 1783, a Spanish squadron of 25 ships bombarded Algiers, but failed to overcome the defenses of the city.[152] The Spanish squadron, composed of four ships of the line and six frigates, did not inflict significant damage on the city and had to withdraw.[153] The commander of this fleet and that of 1784 was Spanish Admiral Antonio Barceló. A European league uniting the Spanish Empire, the Kingdom of Portugal, the Republic of Venice and the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem and composed of one hundred and thirty ships began to bombard Algiers on July 12, 1784. This bombardment was a failure, and the Spanish squadron fell back against the defense of the city. The Dey Mohamed ben-Osman asked for an indemnity of 1,000,000 pesos to conclude a peace in 1785. This was followed by a period of negotiation (1785–87) to achieve a lasting peace between Algiers and Madrid.[154]

Recapture of Oran and Mers el-Kébir

In 1791, the reconquest of Oran and Mers el-Kébir began. Oran, then under Spanish domination, was a concern for the Spanish court. In the 18th century. The Spaniards swung between two imperatives: preservation of their presidency and maintaining a fragile peace with Algiers.[154] The Spanish representative asked the Dey for a truce while he consulted the Council of State in Madrid, in order to study a proposal for the transfer of the two cities. A truce of one month was granted on March 20, 1791.[155] However certain guarantees requested by the Spaniards (concerning the corso and the demolition of the Spanish forts) were considered an offense by Algiers, which ordered the resumption of hostilities in May 1791.[154]

The death of Mohamed Ben-Osman, and the election of Sidi Hassan, his first Secretary of State as Dey, once again gave Spain some respite. As negotiations resumed with Count Floridablanca: Spain undertook to restore "freely and voluntarily" the two cities. In exchange, it had the exclusive right to trade certain agricultural products in Oran and Mers-el-Kébir. The peace treaty was signed in Algiers on September 12, 1791 by Dey Hassan Pasha and ratified in Madrid, on December 12 of the same year, by King Charles IV.[154] On February 12, 1792, the Spanish soldiers evacuated Oran and Mohammed el Kebir Bey entered the city.[156]

Algerian trade issues

The Foreign trade was in the hands of foreigners. Algiers had no merchant navy: the Christians forbade it, not wanting direct trade between Muslims and Christians at any price. Throughout the 18th century, the armed corsairs of Malta had the mission of threatening trade with the Maghreb, of maintaining permanent insecurity against it and of defending the Christian monopoly. These corsairs were encouraged by The main task of the order which was: "to prevent the Turks from loading their goods on the ships of their nation and to keep them under European dependence".[157]

Jewish hegemony on Algerian foreign trade

The Jews of Algiers became an economic power, eliminating many European houses from the Mediterranean, which deeply worried the Marseillais, who sought to defend their threatened monopoly.[lower-roman 4] The French consuls resented the Jews almost violently and urged their King to pass ordinances that would prevent these favored Jews from trading in French ports. It was no use; the Jewish merchants had contacts, they dealt in prize goods from the corsairs as well as in more regular merchandise, and they were essential to the dey's government.[158] Their economic power enabled them to play an important role in the internal and external policy of the Algerian State. The Jews were very skillful in mixing their personal affairs with the interests of the Algerian State, as they were at the origin of various Algerian disputes with Spain and especially with France.[158][159]

French commercial barriers

.jpg.webp)

The French king was obliged to make good the losses to avoid further difficulty, for the French king's government established rules, port regulations, and tariff duties that made it practically impossible for a Muslim merchants to trade in French harbors.[158] Thus, the Algerians could not actually carry their own cargoes of wool, hides, wheat, wax, honey, and other such commodities to the French market.[158] The Marseillais wanted, for example, to prohibit the Algerian Jews from residing more than three days in their port, they appealed to the Dey to induce him to prohibit the Jews from going to trade in Marseilles. The Muslim merchants, who had their cemetery in Marseilles, also wanted to build a mosque, but they were refused. Moreover, the raïs, especially Christian converts to Islam, did not dare to land on Christian land, where they risked imprisonment and torture. Port regulations practically prevented them from trading with Europe in their own ships.[157]

Unable to have commercial vessels, nor therefore to transport their goods themselves to Europe, the Algerians were forced to use the services of foreign intermediaries and to fall back on the Corso again to compensate for the lost money.[157]

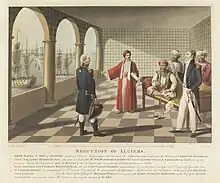

Barbary Wars (1785-1816)

During the early 19th century, Algiers again resorted to widespread piracy against shipping from Europe and the United States of America, mainly due to internal fiscal difficulties, and the damage caused by the Napoleonic Wars.[160] Being the most notorious of the Barbary states,[161] Algiers declared war on the U.S and took part in the Second Barbary War, which culminated in August 1816 when Lord Exmouth executed a naval bombardment of Algiers, the biggest, and most successful.[162] The Barbary Wars resulted in a victory for the American, British, and Dutch navies since it culminated in the weakening of the Algerian navy,[163] and the liberation of 2000 Christian slaves.[164]

French invasion

During the Napoleonic Wars the Regency of Algiers had greatly benefited from trade in the Mediterranean, and the massive imports of food by France, largely bought on credit. In 1827, Hussein Dey, Algeria's ruler, demanded that the restored Kingdom of France pay a 31-year-old debt contracted in 1799 for supplies to feed the soldiers of the Napoleonic Campaign in Egypt.[165]

The French consul Pierre Deval refused to give answers satisfactory to the Dey, and in an outburst of anger, Hussein Dey hit him with his fan. King Charles X used this as an excuse to break diplomatic relations and to start a full-scale invasion of the Algerian Regency on 14 June 1830: Algiers capitulated to the French on 5 July 1830 and Hussein Dey went into exile in Naples.[160] Charles X was overthrown a few weeks later by the July Revolution[165] and replaced by King Louis Philippe I.

Political status

State of Algiers established in 1516

Aruj Barbarossa, a corsair chief, a skilful politician as well as a warrior, feared by the Christian armies in the Mediterranean, nevertheless tried, even at the expense of the Maghreb principalities, to build a powerful Muslim state in the center of the Maghreb. Fray Diego de Haedo, a Spanish Benedictine from Sicily, wrote between 1577 and 1581: "Aruj effectively "began the great power of Algiers and the Barbary".[166]

Aruj sought the support of religious authorities, in particular of maraboutic and sufi orders.[167] Exploiting the popularity of the marabouts for the benefit of his policy, he conveyed to them the idea of the form of government he was considering, called the "Odjak of Algiers".[34] Everything depended on a sort of a military republic, analogous to that of the island of Rhodes occupied by the Christian Knights Hospitaller.[168]

This constitution and the new power of Aruj, with religious sanction and the support of the scimitars of Turks and Christian renegades, allowed him a power freely accepted by the military, making his authority was absolute,[168] accepted without resistance by the population. Power was in the hands of the soldiers of the Odjak, and native Algerians and Kouloughlis were excluded from high government positions.[34]

Khair ad-Din Barbarossa inherited his brother's position without opposition. To contain the revolts of his opponents and fight the Spanish Empire, he pledged allegiance to the Sublime Porte, and had himself recognized as sovereign by the Sultan with the title of beylerbey.[169] The new pasha of Algiers in fact designed the strategy for the existence of the Algerian state. To govern the country, discuss and manage state affairs, he relied on a Council, the Diwân, of carefully-chosen members.[170] Eventually, the members of the Diwân were elected and for the most part came from the corps of janissaries, as in Constantinople.[171] They became, if even they reflected the Ottoman ruling class, "the Algerians" of the state.[172][173]

Ottoman Viceroyalty of Algiers (1519-1659)

After 1516, Algiers became the center of Ottoman rule in northwest Africa.[174] It was also a center of piracy for Muslims who attacked the ships of Christian countries; the island of Malta served Christian pirates in the same way.[174] The Regency was the headquarters of the Algerian Janissary force, probably the greatest in the empire outside of Istanbul. With these powerful forces, Algiers quickly became a bastion of the Islamic world as the West competed with the Ottoman Empire for control of the Western Mediterranean.[175] Until the mid-17th century, power formally rested in the hands of governors sent from Istanbul and replaced every few years. The corsair captains, however, were virtually outside their control, and the janissaries' loyalty was limited by their ability to collect taxes and pay their salaries.[175]

Corsair Kings: Beylerbeylik period (1519-1587)

Between 1519 and 1659, the rulers of the Regency of Algiers were chosen by the Ottoman sultan. In the first few decades, Algiers completely aligned with the Ottoman Empire, since the full authority of the country and the management of its affairs were in the hands of the Beylerbey or "Prince of princes". The beylerbeys were from the sect of Riyas al-Bahr or the corsairs, most of whom were companions of Khair ad-Din Barbarossa himself, and the Ottoman Sultan appointed them over whomever the corsairs suggested as viceroys.[176][177] Often, one remained in power for several years. A number of them were also transferred to Constantinople to assume the position of Kapudan Pasha because of their experience in commanding naval fleets, such as Hayreddin Barbarossa, his son Hassan Pasha, and Uluj Ali Pasha.[49]

However, the beylerbeys were autonomous despite aknowledging the suzerainty of the Ottoman sultan; Spanish Benedictine and historian Diego de Haedo called them "Kings of Algiers",[177] mainly because the "Timar" system was not applied in Algiers, and the beylerbeys would instead send an annual tribute to Istanbul after meeting the expenses of state.[178] Also, the Algerian corso aroused diverging internal and external interests of Algiers and Istanbul, with the latter unable to control it,[179] which eventually led Muhammad I Pasha to unify the corsairs and the janissaries into a single military institution,[180] allowing it to act so independently that it could refuse orders from the sultan or even send back an appointed pasha.[179]

Triennial mandate: Pashalik period (1587-1659)

Fearful of the growing independence of the rulers of Algiers, the Ottoman Empire abolished the beylerbeylik system in 1587, and established in its place the pashalik system, as it divided the Maghreb countries under its dominion into three separate regencies: Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli.[181] The rule of the pashas lasted nearly 72 years, in which twenty-seven pashas successively ruled, some of whom returned to power as many as four times. This period was known for turmoil, chaos and political instability. Yet it was also considered the "Golden Age of Algiers" due to its massive corsair fleet,[182][183] and the riches that filled the coffers of the regency thanks to intensified privateering.[184]

_et_du_Royaume_de_F%C3%A8s.jpg.webp)

Aversion to the Sublime Porte increased in Algiers, mainly because Khider pasha and the Odjak strongly opposed the Ottoman Capitulations.[185] Much like the corsairs, the Odjak grew stronger and expanded its influence very autonomously.[178] Already in 1596, Khider Pasha tried to get rid of the Odjak. A revolt sparked in the city of Algiers, and spread to neighboring towns, but the attempt failed.[186][187]

The latter pashas of Algiers were constantly lost between the demands of the corsairs and the Odjak, or with the population, since they were working to multiply their treasures as quickly as possible while waiting for the end of their three-year term in office. As long as this was the main goal of the pashas, governance became a secondary issue, and little by little actual rule was transferred to the Janissary diwan. The pashas in Algiers, however, lost all influence and respect.[188]

Sovereign Military Republic of Algiers (1659-1830)

The Regency was described by some contemporary observers as a "republic".[lower-roman 5] According to priest and historian Pere dan (1580 –1649): "The state has only the name of a kingdom since, in effect, they have made it into a republic."[190] Algiers showed characteristics of a more "horizontal" and "egalitarian" structure than the European powers which steadily succumbed to the absolutism of the monarchs.[191]

It was unique among Muslim countries, and unusual even in 18th-century Europe, in having its rulers elected through limited democracy. This was even praised by Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[192] Algiers was not a modern political democracy based on majority rule, alternation of power, and competition between political parties. Instead, politics was based on the principle of consensus (ijma), which was legitimized by Islam and by jihad.[192]

In principle, any member of the Janissary Odjak or the corsair captains could aspire to become Dey of Algiers through a system of "democracy by seniority."[190] Any new recruit can rise up through the ranks at the rate of one every three years. Over time, he would serve as commander-in-chief or "Agha of Two Moons" for a two months period. He would then serve in the Divan or great council of government with a vote on all important matters and elections.[190] However, the ruler was elected for life and could only be replaced after his death. Opponents could thus only gain power by overthrowing the current leader, leading to violence and instability. This volatility led many early 18th-century European observers to point to Algiers as an example of the inherent dangers of democracy.[192]

Janissary revolution: Agha regime in 1659

A massive revolution sparked when Ibrahim Pasha took a deduction from the money that the Sultan sent to the corsairs to compensate their losses in the Cretan war.[193] He was arrested and put in prison.[194] Taking advantage of this incident, the commander-in-chief of the Janissaries stationed in Algiers Khalil Agha usurped supreme authority,[195][118] accusing the pashas sent from the Sublime Porte of being mostly corrupt and their government behaviour hindered the regency's affairs with European countries.[196] The Janissaries effectively eliminated the authority of the pasha,[197] whose position became only ceremonial, and they agreed to assign executive authority to Khalil Agha (who inaugurated his rule by building the iconic "Djamaa el Djadid" mosque),[79] provided that the period of his rule does not exceed two months, then they put the legislative power in the hands of the Diwan Council. The Janissaries forced the Sultan to accept their new government under duress, but the Sultan stipulated that the Diwan pay the salaries of the Turkish soldiers. Thus began the era of the Aghas,[118] and the pashalik became a military republic.[198][199][200]

Military chiefs elective: Deylik period (1671-1830)

_-_The_Attack_on_Shipping_in_Bugia%252C_18_May_1671_(II)_-_RCIN_405214_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

The government of the regency underwent another change in 1671 when the destruction of seven Algerian ships by a British squadron commanded by Sir Edward Spragge[201] occasioned a rebellion of the Corsairs and the assassination of Agha Ali (1664–71), the last of four janissary chiefs to rule the country since 1659, all of whom were killed.[53]

Ali Agha's death caught the leaders of the Regency unawares. The Odjak in rebellion tried to pursue the experiment of sovereign Aghas, but the designated candidates recuse themselves one after the other. Under these conditions, the Odjak, with the agreement of the Ta'ifa of Raïs, resurrected the project of the late Ali Bitchin Raïs and resorted to an old expedient already in use in 1644-45, which consisted in entrusting the destiny of the Regency and the charge of the payroll to a Raïs reputed to be solvent, an old Dutch renegade, "Hadj Mohammed Trik".[202][203] They gave him the titles of 'Dey' (maternal uncle) and 'Doulateli' (head of state) and 'Hakem' (military ruler) respectively.[204] Thus, after 1671, the Deys became the main leaders of the country.[202][205] In 1689, eventhough the Dey came to be elected by the Odjak again, the Agha ceased to be ex officio the ruler of Ottoman Algeria.[53]

The Deys-Pashas in the 18th century

The Pashas skilfully tried to regain some of their lost authority, and intrigued in the shadows, stirred up conflicts and fomented sedition to overthrow the unpopular Deys.[195] From 1710 on, the Deys assumed the title of Pasha at the initiative of Dey Baba Ali Chaouch (1710-1718) and no longer accepted a representative of the sultan at their side, thus confirming their independence vis-à-vis the Sublime Porte.[206][207]

The Deys also imposed their authority on the Raïs and the Janissaries.[53] The former did not approve of the provisions which restricted the corso, their main source of income, as they remained attached to the external prestige of the Regency, the latter did not admit military defeats and delays in the payment of their pay. But the Deys ended up triumphing over their revolts. The raïs lost the importance they had had in the 17th century; European reactions, new treaties guaranteeing the safety of navigation and the slowdown in shipbuilding considerably reduced its activity. The Raïs were very unhappy with this situation, but they no longer had the strength to oppose the government. Their revolt of 1729 failed. They had risen up against the Dey Mohamed ben Hassan whom they accused of favoring the Janissaries to their detriment and killed him.[208] The new Dey, Kurd Abdi (1724-1732), quickly restored order and severely punished the conspirators.[209]

Decline of the Dey regime

The monopoly of the military elite on power and its reclusion spread strife and civil unrest among the population witnessing repeated assassinations among the Deys. Also, the repeated attempts of the Ottoman porte to interfere in the affairs of the Algerian state had negative effects on its political stability and motivated hostile factions to rebel and disobey more often, causing in turn a severe reduction of the population and decline in trade.[210] Destructive earthquakes occurred in 1716, 1717, and 1755, the occurrence of epidemics in 1752, 1753, and 1787, and drought in other years, led to the death of thousands, and the spread of poverty and misery. The lack of supplies and agricultural crops also caused popular anger and discontent.[210]

Popular revolts

Since the authorities burdened them with heavy taxes and fines without taking into account their input or financial condition, under the pretext of constant "Holy war" with European states, the people of Algiers were ready to respond positively to every call for disobedience and rebellion, to which the Deys responded with brute force.[211] A number of rebellious movements emerged throughout this era. In 1692: The inhabitants of the capital and the neighboring tribes tried to get rid of Ottoman rule while the Dey Chabane was campaigning in Tunisia. The attempt led to setting fire to the port facilities and some of the ships anchored in it.[212]

The Koulouglis of Tlmecen rebelled against Dey Ibrahim kuçuk and expelled the Turkish garrison from the city and tried to connect with the Koulouglis in Algiers to spread the movement remove Ottoman rulers. But the Dey, aware of the attempt, put an end to it.[213]

The inhabitants of Iflissen in the major tribes staged a rebellion in 1767 that lasted for nearly seven years. Their forces marched to the outskirts of the capital itself and pursued the forces of the Dey in the villages of Metija. Before the disobedience of Iflissen, the population revolted in Blida, Al-Houdna and Isser, and in some oases of the south and Al-Nammasha in the Aures.[214]

Darqawiyyah revolt

In 1792, incidents in Constantine led to the killing of popular Saleh Bey, a prominent administrative figure in the eastern Beylik. Algiers lost a political man and a seasoned military and administrative leader.[215] At the start of the 19th century, intrigues from the Moroccan court in Fez inspired the Zawiyas to stir up unrest and revolt.[216] Where Muhammad ibn Al-Ahrash, a marabout from Morocco and leader of the Darqawiyyah-Shadhili religious order, led the revolution in eastern Algeria, well aided by his Rahmaniyya allies.[217] The Darqawis in western Algeria joined the revolt and besieged Tlemcen, and the Tijanis also joined the revolt in the south. But the revolt was defeated by the bey Osman, who in turn was killed by Dey Hadj Ali.[218]

Administration

.jpg.webp)

The organizations upon which the administrative apparatus of Ottoman Algeria relied were a mixture of borrowed Ottoman systems and local traditions inherited from previous stages of Islamic rule in the Maghreb, especially from Almohad ones, which were adopted by the courts of the Marinids, Zayyanids, and Hafsids. Hence, the Regency of Algiers was represented by an Ottoman styled administrative apparatus influenced by the remains of the Almohad regimes. This was maintained through the regular recruitment of military elements from Ottoman lands in exchange for sending tribute to the Porte.[219]

Algerian Stratocratic institution: The Diwan

The Diwan of Algiers was established in the 16th century by Hayreddin Barbarossa and seated first in the Jenina Palace then in the Casbah citadel. This assembly, initially led by a Janissary Agha, soon evolved from a means to administer the Janissary Odjak of Algiers to a primary institution of the country's administration.[220] Beginning around 1628, the Diwan expanded into two subdivisions, one called the "private (Janissary) Diwan" (diwan khass), and the "public, or Grand Divan" (diwan âm). The latter was composed of Hanafi scholars and preachers, the Raïs, and native notables. It numbered between 800 and 1500 people.[221] But was still less important than the private Divan of the Janissaries. When Algiers was ruled by Aghas, the president of the Diwan was also the leader of the country. The Agha called himself "Hakem" (Ruler).[75]

In the 18th century, the Grand Diwan remained a large council of senior officials, notables, ulamas and senior officers of the Janissary militia, with a total of nearly 700 members. It was this assembly that elected the Dey of Algiers. At the beginning of their mandate, the Deys consulted the divan on all important questions and decrees were deliberated. This council met in principle once a week, but this depended on the Dey, who could ignore the diwan whenever he felt powerful enough to govern alone.[222]

With the growing power of the Deys and the measures taken to protect themselves from the intrigues of the Janissaries of the diwan, these large assemblies gradually lost their influence and only met sporadically by the beginning of the 19th century.[220]

Territorial management

By the end of the 16th century, Algiers reached its frontiers which it secured until 1830.[121] The Regency was composed of various beyliks (provinces) under the authority of beys (vassals):[223]

- The Beylik of Constantine in the east, with its capital in Constantine

- The Beylik of Titteri in the centre, with its capital being Médéa

- The Beylik of the West, with its capital being Mascara and then Mazouna and then Oran

The administration of the western Beylik was established in 1563. The capital was moved to Mazouna in 1710, then to Oran in 1791. The emirate of the southern Beylik was established in 1548, with the capital in Médéa; it was called the Beylik of Tetri. The center of the eastern beylik was the city of Constantine. The central Beylik included the city of Algiers with some nearby ports. As for El Kala, Sebaou, Blida (Bahr al-Azzun), they were called the Black Country and independent leaders were appointed for them. As for Tlemcen, it was given a special status. Sometimes Ténès and Bejaia were linked to the southern Beylik, and sometimes they were considered separate provinces.[224]

Ottoman Algerian administration relied on makhzen tribes. Under the Beylik system, the Beys divided their Beyliks into chiefdoms. Each province was divided into outan, or counties, which were governed by caïds (commanders) under the authority of the Bey to maintain order and collect taxes from tributary regions.[225] Thus the Beys were empowered to exercise a mini administrative system, and succeeded in managing their Beyliks with the help of their commanders and governors among the Makhzen tribes, in return, these tribes enjoyed special privileges including exemptions from paying taxes.[226] This system allowed the state of Algiers to expand its authority over the north of Algeria for three centuries. Despite this, society remained divided into tribes and was dominated by maraboutic brotherhoods and local djouads, or nobles. As a result, certain regions only loosely acknowledged the authority of Algiers, leading to numerous revolts, confederations, tribal fiefs, and sultanates that contested the regency's control.[227] The Bey of Constantine relied on the strength of the local tribes, and at the forefront of those tribes were the Beni Abbas in Medjana and the Arab tribes in Zab region and Hodna, and the chiefs of these tribes were called "the Sheikh of the Arabs".[225]

.jpg.webp) Admiralty of Algiers in 1880, seat of Captain Raïs, harbor master and Wakil al-kharadj (minister of the navy)

Admiralty of Algiers in 1880, seat of Captain Raïs, harbor master and Wakil al-kharadj (minister of the navy) Palace of Mustafa Khodjet al-Khil (secretary of horses)

Palace of Mustafa Khodjet al-Khil (secretary of horses) Inside Ahmed bey Palace, last governor of the eastern Beylik

Inside Ahmed bey Palace, last governor of the eastern Beylik.jpg.webp) Headquarter of the Janissaries by Henri Klein (1910)

Headquarter of the Janissaries by Henri Klein (1910)

Armed forces

Economy

Mandatory royalties and gifts

The Algerian state imposed royalties on the European countries that dealt with it commercially in exchange for allowing them freedom of navigation in the western basin of the Mediterranean. Thus giving the merchants of those countries special privileges, including significant reductions in customs duties. This prevented the character of banditry, piracy, or assault on the freedom of global trade from the part of the Algerian navy.[228] These royalties differed according to the relationship between those countries and Algiers, and the conditions prevailing in that period had an impact on determining the amounts of these royalties, and this is shown in the following table:[229]

| Country | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Spanish Empire | 1785 -1807 | After signing the armistice of 1785 and withdrawing from Oran, it was obliged to pay 18,000 francs. It contributed 48,000 dollars in 1807. |

| Grand Duchy of Tuscany | 1823 | Before 1823, it was obligated to pay the value of 25,000 doubles (Tuscan lira) or 250,000 francs. |

| Kingdom of Portugal | 1822 | It was obligated to pay the value of 20,000 francs. |

| Kingdom of Sardinia | 1746 - 1822 | Following the treaty of 1746, it was forced to pay 216,000 francs up by 1822. |

| Kingdom of France | 1790 - 1816 | Before the year 1790, it paid 37,000 pounds, and after 1790, it pledged to pay 27,000 piasters, or 108,000 Francs. And in 1816, it committed to pay the value of 200,000 francs. |

| United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland | 1807 | It pledged to pay 100,000 piasters, or 267,500 francs, in exchange for some privileges. |

| Kingdom of the Netherlands | 1807 - 1826 | After the treaty of 1826, it committed itself to paying 10,000 Algerian sequin, and in 1807, it paid the value of 40,000 piasters, or 160,000 francs. |

| Austrian Empire | 1807 | The value of the royalties paid in the year 1807 was estimated at 200,000 francs. |

| The United States of America | 1795 - 1822 |  Captain William Bainbridge paying tribute to Mustafa Pasha, dey of Algiers in 1800 |

| Kingdom of Naples | 1816 - 1822 | Paid a royalty estimated at 24,000 francs. In 1822, a royalty of 12,000 francs was paid every two years. |

| Kingdom of Norway | 1822 | Paid a royalty of 12,000 francs every two years. |

| Kingdom of Denmark | 1822 | Paid a royalty of 180,000 francs every two years. |

| Kingdom of Sweden | 1822 | Paid a royalty of 120,000 francs every two years. |

| Republic of Venice | 1747 - 1763 | Since 1747, it has paid a royalty of 2,200 Gold coins annually. In 1763, the value of the royalties imposed on it became estimated at 50,000 riyals (Venetian lira). |

Royalties were imposed on other countries on some occasions, and they were applied to the states of Bremen, Hanover, and Prussia, in addition to the Papal States.[229]

Taxation

The taxes levied by the rulers of the regency included some subject to Islamic law, including the cushr (tithe) on agricultural produce, but added various aspects of extortion.[230] Periodic tithes could only be collected on private land near the town where the crops were grown. But instead of tithes, the inhabitants of mountainous and nomadic tribes had to pay a fixed tax, called garama (compensation), based on a rough estimate of their wealth. In addition, the rural population had to pay a tax known as lazma (obligation) or ma'una (support), designed to help Muslim armies defend the country from Christians. City dwellers had to pay other taxes, including artisan guild dues and market taxes.[231] In addition, the beys also collected gifts (dannush), every six months to the Deys and their chief ministers. Every bey had to personally bring dannush every three years. Meanwhile, his khalifa (deputy) took it to Algiers.[232]

The arrival of a bey or khalifa in Algiers with dannush was a notable event governed by a set protocol governing how he was to be received and when his presents were to be given to the Dey, his ministers, officials and poor people. The honors that the bey received depended on the value of the gifts he brought. Al-Zahar reported that the chief of the western province was expected to pay more than 20,000 doro in cash, half that in jewelry, four horses, fifty black slaves, woollen Tilimsan garments, Fez silk garments, and twenty quintals each of wax, honey, butter, and walnuts . Dannush from the Eastern Province was larger and included Tunisian products such as perfumes and clothing.[230]

Agriculture

Agricultural production benefited the regency even more than corsairing at some point.[49] Fallowing and crop rotation were the most common techniques. Agricultural products were varied: wheat, corn, cotton, rice, tobacco, watermelon and vegetables were the most commonly grown.[233] Allowing for exports and local consumption, cereals and livestock products constituted much of the country's resources[234] (oil, grain, wool, wax, leather). On the outskirts of the towns, the very rich lands (fahs) provided various fruits, vegetables, vines, rice, cotton, blackberries used for breeding silkworms. Grapes and pomegranates were also cultivated. In the mountains, fruit trees, figs and olive trees grew. European travelers, at different times, such as Léon Africanus, Marmol, Haedo, Rotalier all left with a very strong impression of a very rich country.[235]

This wealth came first of all in the quality of the cultivated land, but also in the agricultural techniques which used all the means of the time (ploughs, plows dragged by oxen, donkeys, mules, camels) and in a period of progress in agriculture, particularly in terms of irrigation (timed watering according to surface area) and ingenious water supply supplying small collective dams. Mouloud Gaid attests: "Tlemcen, Mostaganem, Miliana, Médéa, Mila, Constantine, M'sila, Aïn El-Hamma, etc., were always sought after for their green site, their orchards and their succulent fruits."[236]

The majority of the western population south of the Tell Atlas and the people of the Sahara were pastoralists who lived from date cultivation and the products of sheep, goat and camel breeding. Livestock breeding was also the main activity of nomads and semi-nomads who sold their products each time they went north (butter, wool, skins, camel hair), while the population in the north and east settled in villages and practised agriculture. The state and urban notables (mainly Arabs, Berbers, and Kouloughlis) owned lands near the main towns, cultivated by tenant farmers under the "khammas" system.[53] Inside the country, the large "melk" properties, belonging to local feudalism, represented the country's main wealth: vast areas of Algeria's best lands reserved for monoculture (wheat, barley, grazing). Due to the feudal nature of this regime, the distribution of usufruct was not always equitable and certain ousted members found themselves de facto excluded from their land by the tribe.[235]

Manufacturing and craftsmanship

Manufacturing was poorly developed and restricted to shipyards which built frigates of 300 to 400 tons of oak wood from Béjaïa and Djidjel. The small ports of Ténès, Cherchell, Dellys, Béjaïa and Djidjel, were called upon to build shallops, brigs, galiots, tartanes and Xebecs used in fishing and the transport of goods between Algerian ports. Several workshops supported repairs and rope-making. The quarries of Bougie, Skikda and Bab El-Oued extracted stones which served as raw material for buildings, dwellings and fortifications of the Regency. Cannons of all sizes manufactured at the Bab El-Oued foundries were ordered by the Algerian navy for its warships. These cannons were also used for fort batteries and field artillery.[235]

Craftsmanship was rich and was present throughout the country.[234] Cities were centers of great craft and commercial activity.[237] Urban people were mostly artisans and merchants, notably in Nedroma, Tlemcen, Oran, Mostaganem, Kalaa, Dellys, Blida, Médéa, Collo, M'Sila, Mila and Constantine. The most common crafts were weaving, woodturning, dyeing and production of rope and tools.[238] In Algiers, a very large number of trades were practiced, and the city was home foundries, shipyards, workshops, shops, and stalls. Tlemcen had more than 500 looms. Even small towns where links to the rural world remained important had many craftsmen.[239]

Algerian products were still outcompeted by European products, especially after the industrial revolution began in the 1760s. Modern industry was first introduced in the 1820s by Ahmed Bey ben Mohamed Chérif, who opened many manufactories in the east of the country, mainly focused around military production.[240]

Infrastructure

The road system throughout Algeria was poorly developed, and often used neglected Roman roads.[241] Generally transport and trade happened on the back of mules, donkeys, and camels. Rural roads controlled by autonomous Makhzen sheikhs were often unpredictable and sometimes dangerous thanks to bandits, although a few main roads often based on old Roman ones were regularly policed and protected by authorities, such as the main road passing along the coast all the way to Tunis, and another one passing through the main cities of the inland regions.[242]

Algiers possessed its own, very well developed sewage system based on ones found in Constantinople and Iberia.[243]

Trade

Internal trade was extremely important, especially thanks to the Makhzen system, and large amounts of products needed in cities such as wool were imported from inner tribes of the country, and needed products were exported city to city.[244] Foreign trade was mainly conducted through the Mediterranean Sea and land exports to other neighbouring countries such as Tunisia and Morocco.[237] When it came to land trade (both internal and external) transport was mainly done on the backs of animals, but carts were also used. The roads were suitable for vehicles, and many posts held by the Odjak and the Makhzen tribes provided security. In addition, caravanserais (known locally as fonduk) allowed travelers to rest.[244]

Although control over the Sahara was often loose, Algiers's economic ties with the Sahara were very important,[245] and Algiers and other Algerian cities were one of the main destinations of the Trans-Saharan slave trade.[246]

Society