A cat pheromone is a chemical molecule, or compound, that is used by cats and other felids for communication.[1] These pheromones are produced and detected specifically by the body systems of cats and evoke certain behavioural responses.[1][2]

Cat pheromones are commonly released through the action of scent rubbing.[2] As such, one of the main proposed functions of pheromone release is to allow the cat to familiarize itself with its surroundings and other individuals, both in the newborn and adult stages of life.[3][4][5]

Specific cat pheromones that have been chemically identified include the feline facial pheromones F1-F5, the feline appeasing pheromone, and MMB in urine, most of which are associated with distinct feline behaviours.[2][4][6] Some of these chemical makeups have been synthetically reproduced and may be used by cat owners or veterinary professionals looking to change problematic or stress-induced behaviours.[7][8]

Production and detection

The mechanism of chemical communication for felines involves chemical stimuli being secreted or excreted through the urine, faeces, saliva, or glands, with the stimuli being detected through vomeronasal or olfactory systems.[2] There are several scent glands located on felines that deposit pheromones when a cat rubs against an object.[3] This includes the cheek and perioral gland areas, which consist of several structures that secrete pheromones around the chin, cheeks, and lips.[4] Other scent glands for secreting the pheromones include the temporal glands on the sides of the forehead, the circumoral gland around the lips, sebaceous glands, perianal area, head, fingers, and toes.[3]

Cat pheromone detection is often accomplished through an action known as the flehmen response, where the cat lifts its head, slightly opens its mouth, pushes its tongue to the front of its palate, and retracts its upper lip.[7][9]

Related behaviours

Pheromones are first released when a cat is born to establish the mother and kitten relationship. From this point on, the kitten uses the pheromones to establish relationships with other organisms and objects. The release of the pheromones in kittens is through the olfactory system, which is one of the systems that are fully developed at birth.[2] The olfactory chemical cues released by both the mother and the kitten may be used as reference points for newborns to create a relationship with their immediate environment.[8]

The importance of olfactory cues has been experimentally demonstrated in studies where kittens were removed from their nest.[3][10] Those who were able to detect the pheromones returned to their nest quicker, and more often, than those who had lost their ability to detect the pheromones. This showed that pheromones help cats form a bond with their immediate environment.

Additionally, feline appeasing pheromones released by the mother while nursing may chemically enhance mother-kitten bonding and help maintain peace within the litter.[8] The feline appeasing pheromones are also called mother cat's pheromones, and are secreted in the mammary glands near her nipples. These pheromones help the kittens feel content and secure, and further helps the mother identify her kittens if they are separated from her. In short these pheromones are used to reduce tensions and conflict in cats.[11]

Past the newborn stage, chemical stimuli are commonly released through different forms of scent marking or scent rubbing.[2] Specific scent rubbing behaviours include bunting, in which an animal butts the front of its head against an object or individual,[12] and allorubbing, where two cats rub against each other.[13] Another scent rubbing behaviour that releases pheromones is social rolling, in which a cat flops over and rolls onto its backside to extend its body.[2] These types of pheromone releasers helps a cat to familiarize itself with a foreign area or individual, and diminish stress associated with being in a new or conflict-containing location.[3][4][5] When this behaviour occurs between two cats in a colony, it is likely an attempt to exchange scents and chemical stimuli such as pheromones.[13] It has been proposed that this behaviour of dispersing pheromones through scent rubbing also plays a role in visual communication, since the behaviour often coincides with a known individual coming near the cat.[4]

Feline facial and appeasing pheromones

There are five feline facial pheromones that have been identified from the chin, lip, and cheek sebaceous secretions; F1–F5.[2][7] Although the chemical components have been identified for F1 and F5, their natural function and behavioural implications are not yet known.[4] As a whole, facial hormones F2–F4 assist with the marking of territories, however, they also have more specific individual functions.[4]

fraction substance | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oleic acid | 34–41 | 38–62 | 62–86 | 33–39 | 0 |

| caproic acid | 18–32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| trimethylamine | 3–5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2–6 |

| 5-aminovaleric acid | 6–9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9–15 |

| n-butyric acid | 5–15 | 0 | 0 | 14–30 | 2–12 |

| α-methylbutyric acid | 6–9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5–8 |

| palmitic acid | 0 | 17–49 | 13–24 | 0 | 28–37 |

| propionic acid | 0 | 11–23 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid | 0 | 6–15 | 0 | 0 | 8–19 |

| azelaic acid | 0 | 0 | 6–13 | 0 | 7–17 |

| pimelic acid | 0 | 0 | 9–12 | 11–24 | 0 |

| 5β-cholestan acid 3β-ol | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13–27 | 0 |

| isobutyric acid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11–18 |

F2

The feline facial pheromone F2 has been shown to be deposited during a mating behaviour conducted by males.[2] It is released as form of sexual marking, such that the male will rub its face on an object that is in proximity of a potential female partner. Releasing the F2 pheromone at the same time as its visible mating display may make the cat more effective at obtaining a mate.[3]

F3

Feline facial pheromone F3 is a chemical commonly released through object rubbing.[2] It is thought to be important in a cat’s ability to orient itself within its environment and know where it is in relation to its surroundings.[3] It is a territorial signal, in that cats mark the spaces they frequently use.[3] This may help to emotionally soothe the cat, such that being closer to the scent may increase a sense of security and belonging, while reducing anxiety.[2][4]

F4

Also referred to as the "allomarking pheromone",[15] the feline facial pheromone F4's main associated behaviour is allomarking (or allorubbing).[3] This behaviour involves chemical stimuli being released through rubbing onto other cats in social settings.[13] It may also be deposited onto well-known humans in social situations.[3] The release of the F4 pheromone is suggested to be an indication that the individual being rubbed is familiar, and the cat will be less likely to instigate a conflict with them.[2]

Feline appeasing pheromone

In contrast to the facial pheromones, the feline appeasing pheromone is produced by the mammary sebaceous glands of a mother within the first few days of birthing a kitten.[16] Its release occurs through lactation and is linked with maternal bonding.[2] It is thought to play a role in attachment to the mother cat to ensure the kitten feels calm and protected, as well as serving the purpose of increasing harmonious interactions within the litter.[8]

The patent discloses the composition as a mixture of methyl palmitate, methyl linoleate, methyl oleate, methyl stearate, methyl laurate and methyl myristate.[17]

Synthetic pheromones and pheromonatherapy

Since the chemical compositions of natural pheromones have been isolated, this information can be used to construct synthetic solutions of these same compounds and activate a particular behavioural response. These analogous compounds can be used in the form of a diffuser or spray.[18] The use of these synthetic pheromones as a practical application to treat or alter animal behaviour is termed pheromone therapy or pheromonatherapy.[2][18] The efficacy of pheromonatherapy is debated, and its effectiveness may depend on using the proper pheromone for the targeted behaviour in the right quantity.[4] Feline facial pheromones F3, F4, and the feline appeasing pheromone are three that have been artificially manufactured and have a proposed function to modify behaviour.[2][4]

F3 synthetic analogue

The F3 pheromone was the first to be synthetically replicated.[3] Its attempted use is to reduce feline stress and associated behaviours such as excessive grooming, while instead promoting healthier behaviours of playing and eating.[3][4] Recent research has investigated its effects on short-distance transport-related stress, and in a randomized pilot study, it was found that stress-related behaviours including curling, immobility, and meowing were reduced when using a synthetic F3 pheromone product compared to a placebo.[19] It can also be used to help eliminate urine spraying and scratching, which are undesirable scent-marking tendencies.[4] Concerning the problem behaviour related to scratching, a recent controlled study provided evidence of efficacy of this pheromone in reducing scratching behaviour.[20]

Some veterinary texts promote the placement of the F3 synthetic analogue in a location where the cat frequently visits and rests in, since the natural pheromone is thought to reduce distress based on proximity to the chemical.[2] It may also be sprayed onto the bed, cage, or towel of a cat in the veterinary consult room to diminish stress.[2]

F4 synthetic analogue

The F4 synthetic facial pheromone is sometimes used with poorly socialized cats to promote smoother interactions within animals of the same or different species.[4] It is suggested to work by misleading the cat into believing that a newcomer is someone they had previously encountered, therefore, inhibiting aggression and promoting acceptance of the stranger.[4] In a veterinary setting, the F4 pheromone may be rubbed on the professional to make handling easier and reduce escape tendencies for pets who have an immense fear of veterinarians.[15]

Feline appeasing pheromone synthetic analogue

Feline appeasing pheromone, with its route in maternal bonding, is made use of artificially in multi-cat households. When cats are first introduced or are experiencing conflicts, this pheromone may be diffused to alleviate stress and diminish socially tense behaviours, such as stalking and chasing.[8] In a recent pilot study looking at 45 multi-cat households who were experiencing cat conflicts, it was found that aggressive tendencies significantly decreased more in those who used a diffuser containing this pheromone as opposed to a placebo.[21]

Combination treatments

Other interventions, such as positive-reinforcement strategies or providing food puzzles as an enrichment source, may be used along with pheromone therapy to further reduce the incidence of problematic behaviours and promote emotional wellbeing.[2][22] In addition, artificial pheromones may be used simultaneously with pharmacological treatment to increase the likelihood of a positive behavioural result, since they have different routes of action.[18] An example of a combination treatment looked at in the area of veterinary medicine is the use of the feline facial pheromone F3 analogue with clomipramine to treat between cat aggression and urine spraying.[18]

Cat urine odorants

| Cat urine-like odorants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

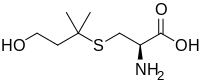

Cat urine, especially that of male cats, contains the putative cat pheromone 3-mercapto-3-methylbutan-1-ol (MMB), a compound that gives cat urine its typical odor. The MMB precursor felinine is synthesized in the urine from 3-methylbutanol-cysteinylglycine (3-MBCG) by the excreted peptidase cauxin. Felinine then slowly degrades into the volatile MMB.[6]

| → |

| Felinine | MMB |

Rats and mice are highly averse to the odor of a cat's urine, but after infection with the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, they are attracted by it, greatly increasing the likelihood of being preyed upon and of infecting the cat.[23]

Cat attractants

Although they are not produced by the cat themselves, and therefore are not pheromones, cat attractants are semiochemical odorants that have an effect on cat behavior and can be used for environmental enrichment. A cat presented with a cat attractant may roll in it, paw at it, or chew on the source of the smell.[24] The effect is usually relatively short, lasting for only a few minutes after which the cats have a refractory period during which the response cannot be elicited. After 30 minutes to two hours, susceptible cats gain interest again.[25]

Various volatile chemicals, iridoid terpenes extracted from essential oils, are known to cause these behavioral effects in cats. Cats are known to respond to catnip (Nepeta cataria), Tartarian honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica), valerian (Valeriana officinalis), and silver vine (Actinidia polygama) to different degrees.[26] The active chemical for catnip and silver vine has been confirmed to be nepetalactone and nepetalactol respectively: they are found in the two plants and synthesized versions of these chemicals trigger similar responses in cats.[27] The active ingredient in Tartarian honeysuckle and valerian may be actinidine, but its effect is yet to be confirmed.[26]

References

- 1 2 Wyatt TD (October 2010). "Pheromones and signature mixtures: defining species-wide signals and variable cues for identity in both invertebrates and vertebrates". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 196 (10): 685–700. doi:10.1007/s00359-010-0564-y. PMID 20680632. S2CID 16824968.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Vitale KR (November 2018). "Tools for Managing Feline Problem Behaviors: Pheromone therapy". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 20 (11): 1024–1032. doi:10.1177/1098612x18806759. PMID 30375946. S2CID 53115782.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Shreve KR, Udell MA (2017). "Stress, security, and scent: The influence of chemical signals on the social lives of domestic cats and implications for applied settings". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 187: 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2016.11.011. ISSN 0168-1591.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Pageat P, Gaultier E (March 2003). "Current research in canine and feline pheromones". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice. 33 (2): 187–211. doi:10.1016/s0195-5616(02)00128-6. PMID 12701508.

- 1 2 Weiss E, Mohan-Gibbons H, Zawistowski S (2015). Animal behavior for shelter veterinarians and staff. Ames, Iowa. ISBN 978-1-119-42131-3. OCLC 905600053.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Miyazaki M, Yamashita T, Suzuki Y, Saito Y, Soeta S, Taira H, Suzuki A (October 2006). "A major urinary protein of the domestic cat regulates the production of felinine, a putative pheromone precursor". Chemistry & Biology. 13 (10): 1071–1079. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.013. PMID 17052611.

- 1 2 3 Hewson C (2014). "Evidence-based approaches to reducing in-patient stress – Part 2: Synthetic pheromone preparations". Veterinary Nursing Journal. 29 (6): 204–206. doi:10.1111/vnj.12140. ISSN 1741-5349. S2CID 85015744.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hargrave C (April 2021). "Pheromones and 25 years of pheromonotherapy: what are they and how do they work?". The Veterinary Nurse. 12 (3): 116–122. doi:10.12968/vetn.2021.12.3.116. ISSN 2044-0065. S2CID 238042295.

- ↑ Tirindelli R, Dibattista M, Pifferi S, Menini A (July 2009). "From pheromones to behavior". Physiological Reviews. 89 (3): 921–956. doi:10.1152/physrev.00037.2008. hdl:11566/296739. PMID 19584317.

- ↑ Mermet N, Coureaud G, McGrane S, Schaal B (September 2007). "Odour-guided social behaviour in newborn and young cats: an analytical survey". Chemoecology. 17 (4): 187–199. doi:10.1007/s00049-007-0384-x. ISSN 1423-0445. S2CID 21280703.

- ↑ What are Cat Pheromones

- ↑ Englar RE (2017). Performing the small animal physical examination. Hoboken, NJ. ISBN 978-1-119-29532-7. OCLC 989520169.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 Crowell-Davis SL, Curtis TM, Knowles RJ (February 2004). "Social organization in the cat: a modern understanding". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 6 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2003.09.013. PMID 15123163. S2CID 25719922.

- ↑ Pageat, Patrick (20 January 1998). "US5709863A Properties of cats' facial pheromones". Google Patents.

- 1 2 Pageat P, Tessier Y (1997). "F4 Synthetic Pheromone: A Means To Enable Handling of Cats With A Phobia Of The Veterinarian During Consultation" (PDF). AGRIS Records, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-30. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- ↑ DePorter TL (January 2016). "Chapter 18 – Use of Pheromones in Feline Practice". In Rodan I, Heath S (eds.). Feline Behavioral Health and Welfare. St. Louis: W.B. Saunders. pp. 235–244. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4557-7401-2.00018-0. ISBN 978-1455774012.

- ↑ Pageat, Patrick (25 January 2017). "Cat appeasing pheromone".

- 1 2 3 4 Mills D (2005). "Pheromonatherapy: theory and applications". In Practice. 27 (7): 368–373. doi:10.1136/inpract.27.7.368. ISSN 0263-841X. S2CID 73157933.

- ↑ Shu H, Gu X (September 2021). "Effect of a synthetic feline facial pheromone product on stress during transport in domestic cats: a randomised controlled pilot study". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 24 (8): 691–699. doi:10.1177/1098612x211041305. PMID 34493099. S2CID 237440871.

- ↑ Pereira Soares, Joana; Demirbas Salgirli, Yasemin; Meppiel, Laurianne; Endersby, Sarah; Pereira da Graça, Gonçalo; De Jaeger, Xavier (18 October 2023). "Efficacy of the Feliway Classic Diffuser in reducing undesirable scratching in cats: A randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled study". PLoS One. 18 (10): e0292188. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0292188. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 10584138.

- ↑ DePorter TL, Bledsoe DL, Beck A, Ollivier E (April 2019). "Evaluation of the efficacy of an appeasing pheromone diffuser product vs placebo for management of feline aggression in multi-cat households: a pilot study". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 21 (4): 293–305. doi:10.1177/1098612X18774437. PMC 6435919. PMID 29757071.

- ↑ Dantas LM, Delgado MM, Johnson I, Buffington CT (September 2016). "Food puzzles for cats: Feeding for physical and emotional wellbeing". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 18 (9): 723–732. doi:10.1177/1098612x16643753. PMID 27102691. S2CID 27014669.

- ↑ Berdoy M, Webster JP, Macdonald DW (August 2000). "Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 267 (1452): 1591–1594. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. PMC 1690701. PMID 11007336.

- ↑ Grognet J (June 1990). "Catnip: Its uses and effects, past and present". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 31 (6): 455–456. PMC 1480656. PMID 17423611.

- ↑ "How does catnip work its magic on cats?". Scientific American. May 29, 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- 1 2 Bol S, Caspers J, Buckingham L, Anderson-Shelton GD, Ridgway C, Buffington CA, et al. (March 2017). "Responsiveness of cats (Felidae) to silver vine (Actinidia polygama), Tatarian honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica), valerian (Valeriana officinalis) and catnip (Nepeta cataria)". BMC Veterinary Research. 13 (1): 70. doi:10.1186/s12917-017-0987-6. PMC 5356310. PMID 28302120.

- ↑ Uenoyama R, Miyazaki T, Hurst JL, Beynon RJ, Adachi M, Murooka T, et al. (January 2021). "The characteristic response of domestic cats to plant iridoids allows them to gain chemical defense against mosquitoes". Science Advances. 7 (4): eabd9135. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.9135U. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd9135. PMC 7817105. PMID 33523929. S2CID 231681044.

External links

- Coates, Jennifer (22 April 2013). "Synthetic Feline Facial Pheromones: Making Recommendations in the Absence of Definitive Data, Part 1". petMD. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2014.