| Battle of Mughar Ridge | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |||||||

.jpg.webp) 3/3rd Gurkha Rifles holding front line trenches | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

XXI Corps Desert Mounted Corps |

Seventh Army Eighth Army | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,188+ |

10,000 prisoners, 100 guns | ||||||

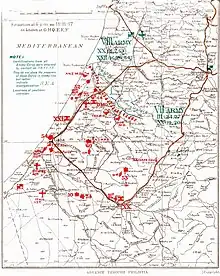

The Battle of Mughar Ridge, officially known by the British as the action of El Mughar, took place on 13 November 1917 during the Pursuit phase of the Southern Palestine Offensive of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in the First World War. Fighting between the advancing Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) and the retreating Yildirim Army Group, occurred after the Battle of Beersheba and the Third Battle of Gaza. Operations occurred over an extensive area north of the Gaza to Beersheba line and west of the road from Beersheba to Jerusalem via Hebron.[1]

Strong Ottoman Army positions from Gaza to the foothills of the Judean Hills had successfully held out against British Empire forces for a week after the Ottoman army was defeated at Beersheba. But the next day, 8 November, the main Ottoman base at Sheria was captured after two days' fighting and a British Yeomanry cavalry charge at Huj captured guns; Ottoman units along the whole line were in retreat.

The XXI Corps and Desert Mounted Corps attacked the Ottoman Eighth Army on an extended front from the Judean foothills across the Mediterranean coastal plain from 10 to 14 November. Beginning on 10 November at Summil, an Ottoman counterattack by the Seventh Army was eventually blocked by mounted units while on 13 November in the centre a cavalry charge assisted by infantry captured two fortified villages and on 14 November, to the north at Ayun Kara an Ottoman rearguard position was successfully attacked by mounted units. Junction Station (also known as Wadi es Sara) was captured and the Ottoman railway link with Jerusalem was cut. As a result of this victory the Ottoman Eighth Army withdrew behind the Nahr el Auja and their Seventh Army withdrew toward Jerusalem.

Background

After the capture of Beersheba on 31 October, from 1 to 7 November, strong Ottoman rearguard units at Tel el Khuweilfe in the southern Judean Hills, at Hareira and Sheria on the maritime plain, and at Gaza close to the Mediterranean coast, held the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in heavy fighting. During this time the Ottoman Army was able to withdraw in good order; the rearguard garrisons retiring under cover of darkness during the night of 8/9 November 1917.[2]

The delay caused by these rearguards may have seriously compromised the British Empire advance as there was not much time to conclude military engagements in southern Palestine. The winter rains were expected to start in the middle of the month and the black soil plain which was currently firm, facilitating the movements of large military units would with the rains become a giant boggy quagmire, impassable for wheeled vehicles and very heavy marching for infantry. With the rains the temperatures which were currently hot during the day and pleasant at night would drop rapidly to become piercingly cold. In 1917 the rains began on 19 November just as the infantry began their advance into the Judean Hills.[3]

The strength of the Seventh and Eighth Ottoman Armies, before the attack at Beersheba on 31 October, was estimated to have been 45,000 rifles, 1,500 sabres and 300 guns. This force had been made up of the Seventh Army's incomplete III Corps. The III Corps' 24th Infantry Division was at Kauwukah (near Hareira–Sheria) and its 27th Infantry Division was at Beersheba. Its 3rd Cavalry Division, as well as the 16th, 19th, and 24th Infantry Divisions were also in the area to the east of the Gaza–Beersheba line. The Seventh Army was commanded by Fevzi Çakmak.[4][5][6] The Eighth Army's XXII Corps (3rd and 53rd Infantry Divisions) was based at Gaza while its XX Corps (16th, 26th and 54th Infantry Divisions) was based at Sheria in the centre of the Gaza–Beersheba line. Supporting these two corps had been two reserve divisions; the 7th and 19th Infantry Divisions. The Eighth Army was commanded by Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein and at that time had an estimated 2,894 officers; 69,709 men; 29,116 rifles; 403 machine-guns and 268 guns.[5][7]

Prelude

During 7–8 November rearguards of the Seventh and Eighth Ottoman Armies delayed the advance of Lieutenant General Harry Chauvel's Desert Mounted Corps, Major General Edmund Hakewill-Smith's (or Major General J. Hill's) 52nd (Lowland) Division, and Major General Philip C Palin's 75th Division.[2][8] The Desert Mounted Corps consisted of the Anzac Mounted Division (Major General Edward Chaytor), the Australian Mounted Division (Major General Henry W Hodgson) and the Yeomanry Mounted Division (Major General George Barrow). The 52nd (Lowland) Division and 75th Division formed part of Lieutenant General Edward Bulfin's XXI Corps.[2][8]

On the coast the 52nd (Lowland) Division was fought a fierce action after crossing the Wadi el Hesi on the coast north of Gaza. By the morning of 8 November, two infantry brigades had crossed the Wadi el Hesi near its mouth and, despite some opposition established themselves on the sand dunes to the north towards Askelon. Sausage Ridge, on their right stretched from Burberah to Deir Sineid, was held in considerable strength, as the ridge covered the road and railway from Gaza to the north. During the afternoon the 155th Brigade moved to attack Sausage Ridge, but it was threatened by a counterattack on the left forcing, the brigade to halt and face north to meet this attack. When the 156th Brigade arrived from Sh. Ajlin on the Wadi el Hesi, the 157th Brigade attacked the southern portion of the ridge, and gained a footing as darkness fell. They lost this precarious position four times to fierce Ottoman counterattacks, before strongly attacking and throwing the defenders off the ridge by 21:00. The two attacking brigades lost 700 men in this action.[9]

The Ottoman rearguards were able to safely get away during the night of the 8/9 November, but during the following day the only infantry unit capable of advancing was the 52nd (Lowland) Division's 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Archibald Herbert Leggett. The division's other brigades were regrouping after the fierce fighting at the Wadi Hesi. The brigade moved to Ashkelon, which was found to be deserted. By evening advance troops had pressed on to Al-Majdal, 16 miles (26 km) from Gaza, where they secured abandoned stores and water.[10][11] By 9 November the Eighth Army had retreated 20 miles (32 km) while the Seventh Army "had lost hardly any ground."[12]

Most of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's infantry divisions were at the end of their lines of communication and were not able to follow up the Ottoman withdrawal. XXI Corps's 54th (East Anglian) Division was forced to rest at Gaza and the Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade at Beit Hanun. In the rear, Lieutenant General Philip Chetwode's XX Corps had transferred its transport to XXI Corps. XX Corps's 60th (2/2nd London) Division (Major General John Shea) was resting at Huj and its 10th (Irish) (Major General John Longley) and 74th (Yeomanry) (Major General Eric Girdwood) Divisions were at Karm. The only units in the field were the 53rd (Welsh) Division (Major General S. F. Mott), corps cavalry, the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, deployed in the front line near Tel el Khuweilfe in the foothills of the Judean Hills north of Beersheba.[13][14][15]

Allenby wrote on 8 November: The battle is in full swing. We have driven the Turks N. and N.E. and my pursuing troops are ten miles beyond Gaza, and travelling fast. A lot of Turks are cut off – just N.E. of Gaza. I don't know if they will be caught; but there is no time to waste in catching them. They pooped off a huge explosion this morning – presumably ammunition. My army is all over the place, now on a front of 35 miles ... My flying men are having the time of their lives; bombing and machine gunning the retreating columns ... I fancy that Kress von Kressenstein is nearing the Jaffa-Jerusalem line, himself.

— Allenby letter dated 8 November 1917[16]

Mounted troop movements on 9 November

.jpg.webp)

Chaytor's Anzac Mounted Division moved off across the maritime plain towards the coast soon after daylight on 9 November, having watered their horses the previous evening.[17][18] The advance was led by two brigades—on the left the 1st Light Horse Brigade and on the right the 2nd Light Horse Brigade rode in line, each responsible for their own front and outer flanks; the attached 7th Mounted Brigade formed a reserve.[19][20][Note 1]

By about 08:30 the 1st Light Horse Brigade had entered Bureir and around an hour later the 2nd Light Horse Brigade was approaching Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein's Eighth Army headquarters at Hulayqat. Here Ottoman soldiers were discovered to be occupying a strong position on high ground north-west of the village; the brigade made a dismounted attack capturing 600 prisoners along with large amounts of supplies, materiel and an abandoned German field hospital.[Note 2] At midday El Mejdel, 13 miles (21 km) north-east of Gaza, was occupied with little difficulty by the 1st Light Horse Brigade, who captured 170 prisoners and found a good well with a steam pump enabling the brigade to water all horses expeditiously. After passing the ancient town of Ashkelon a message was received from the Desert Mounted Corps notifying the Anzac Mounted Division that the British XXI Corps were marching towards El Mejdel and Julis. The main Ottoman road and railway leading north from Gaza were both cut and as a consequence, Chauvel ordered the division to advance towards Bayt Daras. The division duly turned north-east with the 1st Light Horse Brigade entering Isdud close to the Mediterranean Sea. On the right, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade captured the villages of Suafir el Sharkiye and Arak Suweidan, a convoy and its escort (some 350 prisoners). While the brigade was reorganising, Ottoman guns further north opened fire, shelling both captors and captives alike. Just before dark the 2nd Light Horse Brigade captured a further 200 prisoners. The Anzac Mounted Division took up a night battle outpost line along high ground south of the Wadi Mejma, from near Isdud to Arak Suweidan.[19][20]

During its journey across the maritime plain to Isdud, the Anzac Mounted Division captured many prisoners but met no large organised Ottoman force.[21][22] As the day progressed, the captured Ottoman units were found to be increasingly disorganised with many soldiers suffering severely from thirst and exhaustion and some from dysentery.[19][20]

Allenby wrote on 9 November: Things are going well. I have infantry already in Askalon, and am pushing N., inland of that place. I know of 77 guns having been taken; and 5,000 prisoners at least. I went to Gaza, this afternoon ... [it] was taken by Bulfin, quite easily. The attack, on the 6th inst., went with such a rush that Gaza became untenable. Tomorrow is likely to be a critical day, in our pursuit. If the Turks can't stop us tomorrow, they are done.

— Allenby letter to Lady Allenby 9 November 1917[23]

Meanwhile, Hodgson's Australian Mounted Division, spent most of 9 November searching for water, which was eventually found at Huj.[18] After most of the horses had been watered, they advanced 16 miles (26 km) to the Kastina–Isdud line capturing prisoners, guns, and transports on the way. This march during the night of 9/10 November was the only night march made through Ottoman territory of the campaign.[13][24]

The Australian Mounted Division was led by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade as advanced guard, with an artillery battery attached. The 5th Mounted Brigade, two squadrons of which had made the charge at Huj the day before, followed, with the 4th Light Horse Brigade forming the rearguard. To ensure the division maintained its cohesion throughout the night, the advance guard placed pickets along the route every 440 yards (400 m). These were picked up by the following units which in turn dropped pickets to be gathered up by the rearguard. Corps headquarters in the rear was kept informed of the division's movement by signal lamp. Signallers from the two leading brigades intermittently flashed the letters of the divisional call signal in a south-westerly direction from every prominent hilltop along the route. These arrangements worked well and the division arrived intact in the vicinity of Arak el Menshiye and Al-Faluja.[25][Note 3]

The Australian Mounted Division was followed by the 4th Light Horse Brigade Field Ambulance and the divisional train made up of brigade transport and supply sections carrying rations. The field ambulance set up a dressing station and treated about 40 wounded men before moving through Huj at 16:00. After encountering rugged mountainous ravines and 6 miles (9.7 km) of very rough terrain, at around midnight they set up camp in a wadi bed.[26]

The Yeomanry Mounted Division, (Barrow), had been in hills north of Beersheba fighting in the line at Tel el Khuweilfe with infantry from the 53rd (Welsh) Division, the 1/2nd County of London Yeomanry Regiment (XX Corps, Corps Troops) and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade until Allenby ordered it to rejoin the Desert Mounted Corps, 20 miles (32 km) away on the coast. Meanwhile, the infantry from the 60th (2/2nd London) Division marched to Huj during the afternoon of 9 November, obtaining water there. Infantry in the 10th (Irish) and 74th (Yeomanry) Divisions remained at Karm.[13][18][27]

Positions of armies on 10 November

The 52nd (Lowland) Division had ended the possibility of an Ottoman stand on the Wadi Hesi and the next natural defensive line was 7–15 miles (11–24 km) to the north, on the Nahr Sukereir.[21][28][29] Allenby had issued orders on 9 November to advance to El Tineh–Beit Duras in an attempt to turn the Ottoman Nahr Sukereir line before it could be firmly established. Meanwhile, disorganised and demoralised Ottoman columns were harassed as they retreated by the Royal Flying Corps dropping bombs and firing machine-guns.[21][30] Aircraft also dropped bombs on El Tineh railway station and detonated the ammunition depot.[2][31] By 10 November infantry in the 52nd (Lowland) and 75th Divisions had advanced to the line Beit Duras–Isdud with the leading brigade of the 52nd Division successfully attacking a strong Ottoman rearguard defending Isdud.[13]

Despite these difficulties the Ottoman Army successfully carried out a difficult retreat to establish a new defensive position on an extensive and well chosen position. The new line stretched about 20 miles (32 km) west to east from the mouth of the Nahr Sukereir on the Mediterranean Sea to Bayt Jibrin not far from Tel el Khuweilfe in the Judean Hills.[32] The Ottoman Eighth Army on the coastal sector was still retreating when ordered to form the new line along the north side of the valley of the Nahr Sukereir, more than 25 miles (40 km) from Gaza. Further inland the Ottoman Seventh Army was in relatively good condition having retired 10 miles (16 km) or so without interference and was preparing to launch a counterattack.[18]

Reinforcements, transport and supplies were not a problem for these two Ottoman armies as they were falling back on their lines of communication. Their defensive line ran more or less parallel to and 10 miles (16 km) or so in front of both road links and the railway. The Jaffa to Jerusalem railway, with connections northwards to Damascus and Istanbul, had a line branching southwards to El Tineh which branched again to Gaza and Beersheba. These lines could still be used to transport supplies and reinforcements quickly and efficiently to the Ottoman Army's front line. Indeed, a general strengthening of resistance along the Wadi Sukereir line was concentrated around Qastina, towards which the 2nd Light Horse Brigade advanced, capturing a refugee column between Suafir and Qastina.[2][33]

Infantry capture Isdud and Nahr Sukereir

.jpg.webp)

The series of engagements leading up to the Battle of Mughar Ridge began on 10 November near Isdud. The leading brigade of the 52nd (Lowland) Division, the 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, advanced 15 miles (24 km) despite encountering stiff Ottoman resistance around Isdud and was subjected to artillery bombardment from across the Nahr Sukereir. Two brigades of the Anzac Mounted Division followed the 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade pushing across the Nahr Sukereir at Jisr Isdud, to Hamama. Here they successfully established a bridgehead on the Ottoman right flank. Ample water was found and the bridgehead was enlarged the following day.[13][34]

Mounted advance towards Summil

The Australian Mounted Division, which had left Huj after dark on the night of 9/10 November bound for Tel el Hesi, arrived there at 04:30.[Note 4] They halted until dawn on 10 November when several large pools of good water were found in the wadi. These allowed the horses to drink their fill—some that had missed out on watering before the trek, had been without water for three days and four nights. The division then came up into position on the right.[35][36] The Anzac Mounted Division reported on the morning of 10 November that the division was "ridden out" and had to halt for water.[37]

Meanwhile, the 12th Light Horse Regiment (4th Light Horse Brigade) advanced north from Burieh to Al-Faluja arriving at 24:00 on 9/10 November when engineering stores and five burnt out aircraft were captured.[38][39] The 4th Light Horse Brigade was ordered at 10:40 on 10 November to threaten the Ottoman force opposing 3rd Light Horse Brigade on the Menshiye–Al Faluja line.[38][39] Between 08:00 and 10:30, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade had occupied the Arak el Menshiye Station while the 4th Light Horse Brigade entered Al-Faluja 2 miles (3.2 km) to the north-west.[35]

The Australian Mounted Division was joined a few hours later by the Yeomanry Mounted Division which had left Huj early in the morning. They came up on the right of the Australian Mounted Division and took over Arak el Menshiye extending the line a little further east. By the afternoon of 10 November the whole of the Desert Mounted Corps with the exception of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, (still at Tel el Khuweilfe) were in line from a point a little east of Arak el Menshiye to the sea.[40][41] Both the Australian and Yeomanry Mounted Divisions reconnoitred the left half of the Ottoman line running from Qastina, roughly through Balin and Barqusya, to the neighbourhood of Bayt Jibrin in the foothills of the Judean Hills.[38][39]

Chauvel ordered the Yeomanry Mounted Division to move westward to the coast leaving the Australian Mounted Division on the right flank. Neither he nor Hodgson commanding the Australian Mounted Division were aware at that time, that the division was threatened by three or four Ottoman Eighth Army infantry divisions. The 16th and 26th Divisions (XX Corps) and the 53rd Division (XXII Corps) were holding a 6 miles (9.7 km) line between the railway line and Bayt Jibrin, all more or less reorganised and all within striking distance. However, Chauvel's reliance on the steadiness of the Australian Mounted Division was fully justified.[42] With its headquarters at Al-Faluja on 10 and 11 November, the Australian Mounted Division became engaged (during 10 November) in stubborn fighting.[20][39]

Ottoman trenches had been dug from Summil 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Arak el Menshiye to Zeita, 3 miles (4.8 km) to the north-east, and to the east of the railway line.[35][43] The three brigades of the Australian Mounted Division ran into this Ottoman rearguard's left flank near the village of Summil.[44] Ottoman forces were advancing from Summil by 12:55 and the 4th Light Horse Brigade was deployed to attack them with the 3rd Light Horse Brigade assisting.[45] At 14:55 patrols reported strong Ottoman positions along the Zeita–Summil–Barqusya line with trenches extending west of Summil village. Two Ottoman guns were seen being placed in a well-sited position with no cover for 3,000 yards (2,700 m) in front, which would require a long dismounted attack.[38][39] By 15:30 the 4th Light Horse Brigade was approaching Summil when ordered to attack from the north with the 5th Mounted Brigade supported by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade threatening Summil from the west. By 16:30 3rd Light Horse Brigade headquarters were established 870 yards (800 m) south-east of Al-Faluja on the railway line, but owing to darkness at 17:15 the attack was not developed and night battle outpost lines were established at 20:00.[45] By 18:00 the 4th Light Horse Brigade was holding a line linking to the Anzac Mounted Division at Beit Affen, while the Ottomans were holding a ridge near Barqusya with three cavalry troops, three guns and about 1,500 infantry.[38][39] The mounted infantry and cavalry brigades were unable to advance further due to intense Ottoman artillery fire which continued throughout the day. However, Summil was occupied unopposed, during the morning of 11 November.[38][44][45]

The 4th Light Horse Brigade casualties were one other rank killed, one officer and nine other ranks wounded. These wounded soldiers were probably treated by the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance which was in the field a couple of miles past Al-Faluja. The ambulance had itself suffered two casualties when subjected to artillery fire from the hills. But they halted and put up a tent and after dark took in eight more patients all hit by high-explosive shells from the 4th Light Horse Regiment. They were busy until midnight; two seriously wounded soldiers being evacuated to a Casualty Clearing Station and the rest were kept till morning.[46]

My infantry have, on the coast, got 10 miles N. of Askalon; and my Cavalry, further inland, are ahead of them. The mounted troops took some 15 guns and 700 prisoners yesterday ... This afternoon I went to Khan Yunis and told the head men that they could now go out of the town, to their farms and gardens ... The villagers – some 9000 – have been kept in, by wired enclosures, up to now as the Turks had agents there, and many warm sympathizers.

— Allenby's letter to Lady Allenby dated 10 November 1917[47]

Position on 11 November

Allenby decided that an advance on Junction Station could most easily be made from the south-west, by turning the Ottoman Army's right flank on the coast. The 11 and 12 November were days of preparation for battle the following day. The Anzac Mounted Division were resting at Hamama when their supporting Australian Army Service Corps personnel caught up and distributed supplies for man and horse. This task was performed by "B" echelon wagons of brigades' transport and supply sections forming an improvised Anzac Divisional Train. It was here also that the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade rejoined the division at 23:00 on 12 November.[48][49]

Supplies for the advance were transported over land and by sea but it was only with great difficulty that two infantry divisions of XXI Corps and three mounted divisions of Desert Mounted Corps were maintained in the advance at such distances from base. The Navy transported stores to the mouths of the Wadi Hesi and the Nahr Sukherier as these lines were secured. The railhead was being pushed forward as rapidly as possible, but did not reach Deir Suneid until 28 November. So it was a considerable distance over which the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps worked to bring up supplies.[50]

The Australian Mounted Division occupied Summil unopposed at dawn on 11 November but was unable to advance in the face of gathering opposition from the immediate north-east.[44] Summil had been found deserted at 06:00 by patrols of 3rd Light Horse Brigade (Australian Mounted Division). But by 09:30 the 10th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade) reported Ottoman units in strength, holding a high ridge 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north-east of the town. At the same time Ottoman field guns began shelling Summil from a position on high ground about 3 miles (4.8 km) east of the town. Following instructions from Australian Mounted Division received at 14:00, the 10th Light Horse Regiment carried out active patrolling. They made themselves as conspicuous as possible without becoming seriously engaged while the remainder of the division advanced north.[45][Note 5]

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was ordered to rejoin the Anzac Mounted Division. The brigade left Beersheba at 16:30 on 11 November and made a forced march of 52 miles (84 km). Their Auckland Mounted Rifle Regiment, which had been in the front line with the 53rd (Welsh) Division about Tel el Khuweilfe in the southern Judean Hills not far from Hebron, made a forced march of 62 miles (100 km). These treks were estimated to have taken 181⁄2 hours, with a halt to rest and water at Kh. Jemmame early on 12 November. They arrived at Hamama that night at 23:00 some 30 and 1/2 hours later.[48][49]

Allenby prepares for battle as Kress counterattacks

The 20 miles (32 km) defensive line, chosen by the Ottoman commanders to rally their 20,000-strong army and stop the invasion, was also designed to protect the Jaffa to Jerusalem railway and the threatened Junction Station. Their choice of position was partly dictated by pressure from the British, Australian, Indian and New Zealand advance, and partly by the terrain. The line north of the Nahr Rubin ran nearly north–south and parallel to, but about 5 miles (8.0 km) to the west of the railway line branching southwards. It ran along a high steep ridge connecting the hillside villages of Al-Maghar and Zernukah (surrounded by cactus hedges) and extended north-westwards to El Kubeibeh. The southern extremity of this ridge commanded the flat country to the west and south-west, for a distance of 2 miles (3.2 km) or more. Prisoners from almost every unit of the Ottoman Army were being captured indicating that rearguards had been driven back in on the main body of the two Ottoman armies. All along their line Ottoman resistance grew noticeably stronger.[51][52][53]

The Ottoman line was defended by the Eighth Army's 3rd Division (XXII Corps) to the north, the 7th Division (Eighth Army Reserve) to the east, the 54th Division (XX Corps) near el Mesmiye and the 26th Division (XX Corps) holding Tel es Safi.[54] Erich von Falkenhayn, the overall commander of the Ottoman Armies, had resolved to make a stand in front of Junction Station and succeeded in deploying his forces by the evening of 11 November. He ordered a counterattack against the British right flank which was covered by the Australian Mounted Division. His plan was to overwhelm them, cut their supply lines, outflank and capture all the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's forward units. Originally ordered for 11 November it was postponed until the next day.[55]

Meanwhile, Allenby's plan for 13 November was to turn the right flank of the Ottoman line on the coast despite aircraft and cavalry reconnaissances revealing a considerable Ottoman force further inland on the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's own right flank. He assigned the task of dealing with this immediate threat to the Australian Mounted Division, which was ordered to make as big a demonstration of their operations as possible. This would further focus Ottoman attention away from the coastal sector where the Anzac and Yeomanry Mounted Divisions would advance northwards to attempt to turn the Ottoman right flank assisted by infantry attacks on the Ottoman right centre the following day.[56][57]

Allenby's force was deployed with infantry from the 52nd (Lowland) Division and the 75th Division in the centre, the Australian Mounted Division on their right flank with the Anzac and Yeomanry Mounted Divisions on the infantry's left flank.[58][59] He ordered the 52nd (Lowland) Division to extend their position across the Nahr Sukereir on the Ottoman right flank.[60] And, reinforced with two additional brigades, he ordered the Australian Mounted Division to advance towards Tel es Safi where they encountered a determined and substantial Ottoman counterattack.[48][61]

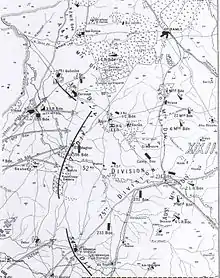

Infantry attack Brown Hill, 12 November

The 52nd (Lowland) Division was to make a preparatory attack near the coast to open the way for the attack on Junction Station the next day. They were to attack north of the Nahr Sukhereir between the villages of Burqa and Yazur with the Yeomanry Mounted Division acting as flank guard.[60][62][63] Their objective was an important Ottoman rearguard position which ran from the village of Burqa to Brown Hill. While the village was easily taken it was necessary to make an extremely difficult attack on the steep sided Brown Hill. The hill was topped by a large cairn and commanded a long field of fire over the plain southwards across the Nahr Sukhereir.[64] By the time a battalion of the 156th Brigade, covered by two batteries of the 264th Brigade Royal Field Artillery and the South African Field Artillery Brigade of 75th Division, captured the crest it had been reduced to a handful of men. But just 20 minutes after taking Brown Hill the remnants of the Scots battalion (now down to just one officer and about 100 men) was unable to withstand an Ottoman counterattack and was driven off after a fierce struggle at close quarters.[65]

The 2/3rd Gurkha Rifles were then ordered to renew the attack at dusk. Owing to poor light, the artillery was no longer able to give much assistance, but nevertheless the Gurkhas quickly retook the hill with a bayonet charge, suffering 50 casualties, and in the process recovering two Lewis guns. The attacking battalion suffered over 400 killed or wounded, while the defending Ottoman 7th Division must have also suffered heavy casualties; 170 dead Ottoman soldiers were found on the battlefield.[66] The fighting here has been described as equal to the 157th (Highland Light Infantry) Brigade's encounter at Sausage Ridge on 8 November.[43] The success of these operations north of the Nahr Sukhereir opened the way for the main attacks the following day, on the Ottoman armies' front line positions.[59]

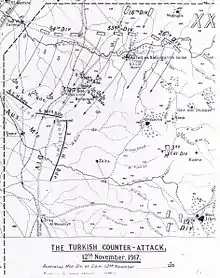

Ottoman counterattack Australian Mounted Division, 12 November

.jpg.webp)

Meanwhile, the Australian Mounted Division advanced in the direction of Tel es Safi to press the left flank of the Ottoman forces as strongly as possible.[57] About 4,000 Australian and British mounted troops of 3rd and 4th Light Horse and 5th Mounted Brigades moved northwards in a conspicuous demonstration of aggression. At first it appeared that the Ottoman formations had retired altogether; the 9th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade) rode through Barqusya, one troop pressing on to occupy Tel es Safi. The 5th Mounted Brigade also found Balin unoccupied, and rapidly advanced northwards towards Tel es Safi and Kustineh. By 12:00 the Australian Mounted Division was spread over at least 6 miles (9.7 km) facing the north and east when four divisions of the Ottoman 7th Army (about 5,000 soldiers) began their advance southwards from the railway.[40][67]

The Ottoman infantry divisions began moving south from El Tineh 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Qastina from the Ottoman controlled branch line of the railway line running southwards in the direction of Huj. Here and further north along the railway trains were stopping to allow huge numbers of troops to take to the field. Soon after the 11th Light Horse Regiment (4th Light Horse Brigade) was forced to retire from Qastina as Ottoman units occupied the place in strength. Then at 12:00 three separate columns (of all arms) were seen advancing towards Tel es Safi from the north and north-east.[68] Ten minutes later the British Honourable Artillery Company battery opened fire, but was hopelessly out shot, outnumbered, and out ranged by Ottoman guns of greater power and weight.[69]

The approach of the Eighth Ottoman Army's XX Corps (16th, 26th 53rd and 54th Divisions) was at first unknown to the 5th Mounted Brigade in Balin. But at about 13:00 a force estimated at 5,000 Ottoman soldiers suddenly attacked and almost surrounded the mounted brigade. The attack was made by two Ottoman columns, one coming down the track from Junction Station to Tel el Safi and the other by rail to El Tineh Station. It was by far the heaviest counterattack experienced since the break through by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force at Sharia on 7 November. The Royal Gloucestershire Hussars and Warwickshire Yeomanry regiments of 5th Mounted Brigade, were pushed back out of Balin before being reinforced by the Worcestershire Yeomanry. The 3rd Light Horse Brigade was sent up at a canter from Summil, followed by the remaining two batteries of the Australian Mounted Division. One light horse regiment occupied Berkusie but was forced to retire by an attack from a very strong Ottoman force supported by heavy artillery fire from several batteries. All available troops of the Australian Mounted Division were now engaged and the Ottoman attack continued to be pressed.[61][70][71] The counterattack forced the mounted division to concede the territory gained during the day, before fighting the Ottoman Army to a standstill in front of Summil.[69]

The 4th Light Horse Brigade could render no effective aid to the 3rd Light Horse or the 5th Mounted Yeomanry brigades. It was strung out to the west as far as the Dayr Sunayd railway line and was being heavily attacked. Ottoman units managed to advance to within 100 yards (91 m) of the 4th Light Horse Brigade's position; only at the end of the day was this strong Ottoman attack repulsed by machine-gun and rifle fire. Hodgson (commander of the Australian Mounted Division) ordered a slow withdrawal by 3rd Light Horse and 5th Mounted Brigades to high ground on the line Bir Summil–Khurbet Jeladiyeh. The order had only just been given when another Ottoman train was sighted moving to the south. It stopped west of Balin and disgorged a fresh force of Ottoman soldiers who deployed rapidly to advance against the left flank of the 5th Mounted Brigade. Two batteries of Australian Mounted Division were in action on the high ground north-west of Summeil firing on this fresh Ottoman force moving over the open plain in full view of the gunners. The artillery fire was so effective the attacking Ottoman advance was halted, forcing them to fall back a little where they dug trenches. Fighting steadily and withdrawing skilfully, the 3rd Light Horse and 5th Mounted Brigades had reached the edge of Summil village where the Ottoman attack was finally held. The attack ended at 18:00 in darkness.[72][73]

The Ottoman attackers dug themselves in on a line through Balin and Berkusie while the line taken up by the Australian Mounted Division began with the 3rd Light Horse Brigade facing east on a line running due north from about halfway between Iraq el Menshiye and Summil. The line then turned westward so the 5th Mounted Brigade faced northwards in front of Summil with the 4th Light Horse Brigade to their left in front of Ipseir and connecting with the right of the infantry division; the 75th Division at Suafir esh Sharqiye. A critical situation created by the strong Ottoman attacking forces had been controlled by the coolness and steadiness of the troops, especially the machine-gun squadrons of the 5th Mounted and the 4th Light Horse Brigades. The Australian Mounted Division suffered about 50 casualties mainly from the 5th Mounted Brigade.[74]

To the east von Falkenhayn, held his reserve force of 3rd Cavalry Division (Seventh Army's III Corps) and 19th Division (Eighth Army reserve) in front of Beit Jibrin.[5][75] They waited throughout the day for the main attack to make progress before beginning their own advance, but the opportunity never eventuated.[40][69][76] This powerful Ottoman counterattack had been contained and had not forced any rearrangement of the invading forces, whose preparations and concentration on the plain were now complete. But von Falkenhayn was forced to halt his Seventh Army's attack and then to take away from it the 16th Division plus one regiment.[77]

Battle

In southern Palestine the wet season was approaching with another thunderstorm and heavy rain on the night of 11 November. The dark cotton soil over which the Egyptian Expeditionary Force was now advancing would not need much more rain to turn it into impassable mud. But 12 November had been fine and the roads had dried out. The rolling maritime plain was dotted with villages on low hill tops surrounded by groves and orchards. These were in turn surrounded by hedges of prickly pear or cactus, making them strong natural places of defence. In the distance to the right the spurs and valleys of the Judean Hills were visible even to the invading British Empire troops near the Mediterranean coast. On 13 November the weather was clear and fine with at first no sign of the Ottoman Army.[78]

The 20,000-strong Ottoman force was deployed to defend the Jaffa to Jerusalem railway along the Wadi al-Sarar and Al-Nabi Rubin.[Note 6] The battlefield was generally cultivated but with winter approaching it was bare and open. Its most prominent feature, the 100-foot (30 m) high ridge which continues north towards Zernukah and El Kubeibeh formed the backbone of the Ottoman Army's 20-mile (32 km) long defensive position. The naturally strong Ottoman line was defended by the Eighth Army's 3rd Division (XXII Corps) to the north, the 7th Division (Eighth Army Reserve) to the east, the 54th Division (XX Corps) near el Mesmiye and the 26th Division (XX Corps) holding Tel es Safi.[54] Benefiting from the terrain two strong defensive positions with commanding views of the countryside were located on the ridge. They were the villages of Qatra and Al-Maghar. These villages were separated by the Wadi Jamus which links the Wadi al-Sarar with the Nahr Rubin.[52][53][79]

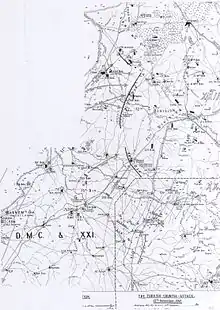

While the Ottoman counterattack had been in progress on 12 November, Allenby issued orders for the attack on 13 November to the commanders of XXI Corps and Desert Mounted Corps at the latter's headquarters near Julis.[79] The main attack was to be carried out by the XXI Corps' 52nd (Lowland) and 75th Divisions westwards towards Junction Station between the Gaza road on the right, and El Mughar on the left.[62] On the right flank of the XXI Corps the Australian Mounted Division's 3rd and 4th Light Horse and 5th Mounted Brigades, reinforced by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade (Anzac Mounted Division), the 7th Mounted Brigade (Yeomanry Mounted Division) and two cars of the 12th LAM Battery, would attack in line advancing northwards towards Junction Station.[80] The remainder of Desert Mounted Corps; the Anzac and Yeomanry Mounted Divisions would cover the left flank of XXI Corps, with Yibna as their first objective and Aqir the second.[58] As soon as Junction Station was captured they were to swing north to occupy Ramla and Lod and reconnoitre towards Jaffa.[59]

In the centre

During the first phase of the attack by infantry in the 75th Division (XXI Corps) were to capture the line Tel el Turmus–Qastina–Yazur and then seize Mesmiye. On their left infantry in the 52nd (Lowland) Division were to secure the line Yazur–Beshshit and then seize Qatra. After a pause for the artillery to be brought forward, the second phase attacks on the final objectives of Junction Station for the 75th and al-Mansura for the 52nd (Lowland) Divisions were to be made. The first phase was due to start at 08:00 hours on 13 November preceded by one hour's bombardment.[79]

By 10:00 the 2/4th Somerset Light Infantry, 1/5th Devonshire Regiment, 2/5th Hampshire Regiment, 1/4th Wiltshire Regiment, 2/3rd and 3/3rd Gurkha Rifles (from the 232nd and the 233rd Brigades, 75th Division) were advancing along the main road. They occupied the undefended villages of Tall al-Turmus, Qastina and Yazur.[81] The 52nd (Lowland) Division had already occupied Bashshit.[82] The 75th Division proceeded to attack Mesmiye on a lower and southward extension of the ridge on which Qatra and el Mughar were situated with the 52nd (Lowland) Division attacking directly towards these two villages. But these attacks were held up by very strong Ottoman defences.[59][83]

At Mesmiye the Ottoman Army was strongly posted on high ground in and near the village, and well-sited machine-guns swept all approaches. Infantry in the 75th Division made steady slow progress; the main body of the Ottoman rear guard eventually falling back to a slight ridge 1 mile (1.6 km) to the north-east. The attack by 3/3rd Gurkhas and infantry in the 234th Brigade moved up to Mesmiye el Gharbiye and cleared the place of snipers. One company of 58th Vaughan's Rifles suffered heavy casualties during an Ottoman attack on the flank of infantry in the 233rd Brigade. Towards dusk the final stage of the infantry assault was supported by two troops of 11th Light Horse Regiment (4th Light Horse Brigade), who galloped into action on the infantry's right flank and gave valuable fire support. An infantry frontal attack covered by machine-gun fire drove the Ottoman defenders off the ridge, enabling Mesmiye esh Sherqiye to be occupied soon after. With Ottoman resistance broken infantry in the 75th Division pushed on through Mesmiye where they took 300 prisoners, and although ordered to capture Junction Station they halted short of their objective in darkness.[84][85][86]

On the flanks

.jpg.webp)

The Australian Mounted Division covered the right flank of the infantry divisions. At 10:00 the 4th Light Horse Brigade moved forward but was held up by an Ottoman position covering El Tineh. The brigade was ordered at 11:50 to push forward to protect the right of the 233rd Brigade (75th Division) as their attack had succeeded and they advanced to occupy Mesmiye. In order for the 4th Light Horse to move the 7th Mounted Brigade was ordered to relieve them in the line.[87] At 12:00 troops of the 4th Light Horse Brigade entered Qazaza 2 miles (3.2 km) south-south-east of Junction Station with the 7th Mounted Brigade on its left then only .5 miles (0.80 km) from the station.[80] By 16:00 the 4th Light Horse Brigade was ordered to push forward to El Tineh as the infantry advance on their left was progressing. It was occupied the following morning.[87]

The Yeomanry Mounted Division, with the Anzac Mounted Division in reserve, covered the infantry's left flank. Yibna was captured by the 8th Mounted Brigade which then advanced northwards against El Kubeibeh and Zernukah.[88] The 22nd Mounted Brigade was held up by Ottoman units defending Aqir while the 6th Mounted Brigade (with the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade protecting their northern flank) was directed against el Mughar.[89][90]

Charge at El Mughar

At about 11:30 the two leading battalions of the 155th (South Scottish) Brigade (52nd (Lowland) Division) were advancing under heavy shrapnel and machine-gun fire to the shelter of the Wadi Jamus about 600 yards (550 m) from their objective.[Note 7] But every attempt to leave the wadi was stopped by very heavy fire from well placed machine-guns. The reserve battalion was brought up but an attempt to work up the wadi between Qatra and El Mughar was barred by heavy machine-gun fire from the villages.[82] At about 14:30 it was agreed between the GOC 52nd (Lowland) Division and the GOC Yeomanry Mounted Division that the 6th Mounted Brigade should attack El Mughar ridge in combination with a renewed assault on Qatra and El Mughar by the 52nd (Lowland) Division. Half an hour later the Royal Buckinghamshire Yeomanry and the Queen's Own Dorset Yeomanry, already in the Wadi Jamus, advanced in column of squadrons extended to four paces across 3,000 yards (2.7 km) at first trotting then galloping onto the crest of the ridge.[83] They gained the ridge but the horses were completely exhausted and could not continue the pursuit of the escaping Ottoman units down the far side.[91] The charge cost 16 killed, 114 wounded and 265 horses; 16 per cent of personnel and 33 per cent of horses.[89] However, the Ottoman defenders continued to hold El Mughar village until two squadrons of the Berkshire Yeomanry of the 6th Mounted Brigade fighting dismounted, with two battalions of the 155th (South Scottish) Brigade (52nd (Lowland) Division), renewed the attack.[83][92] Fighting in the village continued until 17:00 when they succeeded in capturing the two crucial fortified villages of Qatra and El Mughar but at a cost of 500 casualties.[62][93] Two field guns and 14 machine-guns were captured. The prisoners and dead amounted to 18 officers and 1,078 other ranks and more than 2,000 dead Ottoman soldiers.[94][95]

Aftermath

Junction Station was occupied during the morning and during the following days other villages in the area were found to have been abandoned.[96]

Units of the 75th Division supported by several armoured cars occupied Junction Station during the morning of 14 November cutting the Jaffa to Jerusalem railway. Seventeen days of operations virtually without rest, had resulted in an advance of 60 miles (97 km) from Beersheba; major and minor engagements occurring on 13 of those days. Most of the mounted units had covered at least 170 miles (270 km) since 29 October 1917 capturing 5,270 prisoners and over 60 guns and about 50 machine-guns. At Junction Station two train engines and 60 trucks in the station were captured along with an undamaged and fully functioning steam pumping plant which supplied unlimited, easily accessible water.[91][97][98] Junction Station, with its branch line running south to El Tineh and extensions southwards towards Beersheba and Gaza was an important centre for both sides' lines of communication.[68][99]

On 14 November at 06:30 4th Light Horse Brigade entered El Tineh with the rest of the Australian Mounted Division following a couple of hours later. Here good wells containing plenty of water were found but without steam pumps and so watering was not complete until 16:00.[100][101] The horses had done all that had been asked of them, existing during this time on only 91⁄2 lbs of grain ration (practically no bulk food) and scarce water while all the time carrying about 21 stone (290 lb). That they were able to carry on into the Judean Hills after only a limited period of rest established a remarkable record.[91] Meanwhile, the Australian Mounted Divisional Supply Train followed the fighting units as closely as they could, moving out from Beersheba via Hareira and Gaza on 11 November to Isdud on 14 November; to Mesymie the day after and Junction Station on 16 November.[102]

During 14 November infantry in the 52nd (Lowland) and 75th Divisions concentrated and reorganised their ranks. The advance was taken over by the Yeomanry Mounted Division which crossed the railway north of Junction Station and the Anzac Mounted Division which pressed the retreating Ottoman Army northwards near the coast.[96]

On 14 November the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade (commanded by Brigadier General William Meldrum) ran into a determined and well entrenched Ottoman rearguard near Ayun Kara, which they attacked. Fierce close quarter fighting against the Ottoman 3rd Infantry Division continued during the afternoon.[103] Although severely threatened, the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade eventually prevailed and went on to occupy Jaffa two days later.[104]

The Anzac Mounted Division had been ordered to cut the road linking Jaffa to Jerusalem by capturing Ramleh and Ludd.[105] This was the only main road from the coast through Ramleh up the Vale of Ajalon to Jerusalem.[29] During the morning Meldrum's New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade crossed the river close to the sand dunes with 1st Light Horse Brigade on its right. By 09:00 El Kubeibeh had been occupied by the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade before pushing on towards the Wadi Hunayn. Here Ottoman rearguards were encountered in the orange groves and on the hills between El Kubeibeh and the sand dunes.[106] About noon the 1st Light Horse Brigade drove an Ottoman rearguard from a ridge facing Yibna where the Anzac Mounted Division had bivouacked the night before and occupied the village of Rehovot also called Deiran.[107][108] At the same time the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade fought off a strongly entrenched rearguard at Ayun Kara. After conceding considerable ground the Ottoman soldiers made a vigorous counterattack but were finally defeated.[84]

15–16 November 1917

At midnight on 14 November Falkenhayn ordered a general withdrawal and in the days following the Ottoman Seventh Army fell back into the Judean Hills towards Jerusalem while the Eighth Army retreated north of Jaffa across the Nahr el Auja.[109] The Ottoman armies suffered heavily and their subsequent withdrawal resulted in the loss of substantial territory; between 40–60 miles (64–97 km) was invaded by the British north of the old Gaza–Beersheba line. In its wake the two Ottoman armies left behind 10,000 prisoners of war and 100 guns.[110][111]

The day after the action at Ayun Kara, the 75th Division and the Australian Mounted Division advanced towards Latron where the Jaffa to Jerusalem road enters the Judean Hills, while the Anzac Mounted Division occupied Ramleh and Ludd. An Ottoman rearguard above Abu Shusheh blocked the Vale of Ajalon on the right flank of the advance on Ramleh. This rearguard position was charged and overwhelmed by the 6th Mounted Brigade (Yeomanry Mounted Division).[112] On 16 November Latron itself was captured and the first British unit to enter Jaffa; the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade (Anzac Mounted Division) occupied the city, without opposition.[96][113] They administered Jaffa until representatives of the director of Occupied Enemy Territory arrived.[114] And marking the end of the British Empire's first advance into Palestine, the Ottoman Eighth Army retired to the northern bank of the Auja River some 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Jaffa and the Seventh Army retreated into the Judean Hills.[115] Since the advance from Gaza and Beersheba began very heavy casualties and losses had been inflicted. The invasion had spread 50 miles (80 km) northwards into Ottoman territory while over 10,000 Ottoman prisoners of war and 100 guns had been captured by the victorious Egyptian Expeditionary Force.[111][116]

Desert Mounted Corps medical support

The three divisional receiving stations of the Anzac, Australian and Yeomanry Mounted Divisions operated in echelon. As soon as one had evacuated all wounded to the rear, they moved ahead of the other two divisional receiving stations to repeat the process. However, from the beginning there were problems evacuating casualties caused by the lack of linking infrastructure, one receiving station lost all its transport, and the light motor ambulances of another disappeared. The greatest difficulty were of communication and traveling including mechanical breakdowns on the rough roads and tracks which quickly became impassable for motor traffic.[117]

Advance into Judean Hills

The advance towards Jerusalem began on 19 November and the city was captured during the Battle of Jerusalem on 9 December, three weeks later.[118]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was fighting north of Beersheba near Tel el Khuweilfe with the XX Corps Cavalry Regiment and infantry from the 53rd (Welsh) Division.[Falls 1930 Vol. 2 Part I p. 126]

- ↑ While fighting on foot, one quarter of the light horsemen were holding the horses, a brigade became equivalent in rifle strength to an infantry battalion. [Preston 1921 p.168]

- ↑ Preston claims the march was made from Huj to Tell el-Hesi arriving at 04:30 on 10 November. [Preston p. 61] The Australian Mounted Division's General Staff War Diary AWM4-1-58-5 describes the division marching at 23:00 from Huj station to Arak el Menshiye - Faluje via the north side of Kh el Humum, Eh. Zeidan and Tel el Hesy which was reached at 04:30 on 10 November. [Australian Mounted Division War Diary November 1917 AWM4-1-58-5] Falls Sketch Map 9 shows the Wadi Hesi and Tel el Hesi no more than 5 miles (8.0 km) north of Huj while Al-Faluja and Araq el Menshiye (the destinations given by Wavell) are at least 10–12 miles (16–19 km) to the north with Es Dud (the destination given by Keogh) another 5 miles (8.0 km) further on again.[Keogh 1955, p. 168; Wavell 1968 pp. 150–1] It is much more likely the Australian Mounted Division moved from Huj to Arak el Menshiye and Faluja as Wavell suggests or to Es Dud as Keogh suggests as the division was in a position to attack Al-Faluja and Araq el Menshiye on the morning of 10 November.

- ↑ As the Australian Mounted Division was in a position for the 3rd and 4th Light Horse Brigades to occupy Al-Faluja and Araq el Menshiye some 10 to 12 miles north of Huj in the morning, it is very unlikely the division took the night to move 5 miles from Huj to Wadi el Hesi as shown on Falls Sketch Map 9 above.

- ↑ Ottoman railway stations were located at El Tineh, El Affulleh, Ramleh, and Wadi es Sara (known by the British as 'Junction Station'). [Grainger 2006, p. 162]

- ↑ DMC's Operation Order 7 estimates 13,000 on Beit Jibrin – Qastina – Burkah line. [AMD Gen.Staff War Diary 13/11/17 AWM4, 1/58/5]

- ↑ There is one reference to the 'Wadi Katrah' which has been changed to 'Wadi Jamus' to preserve consistency. [Keogh 1955, p. 172]

- Citations

- ↑ Battles Nomenclature Committee 1922, p. 32

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grainger 2006, p. 159

- ↑ Gullett 1941, p. 491

- ↑ Bruce 2002, p. 125

- 1 2 3 Wavell 1968, p. 114

- ↑ Erickson 2007, pp. 115–6

- ↑ Erickson 2007 p. 128

- 1 2 Preston 1921, p. 58

- ↑ Wavell 1968 pp. 148–9

- ↑ Grainger 2006, p. 158

- ↑ Preston 1921, p. 60

- ↑ Erickson 2001 p. 173

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wavell 1968, pp. 150–1

- ↑ Bruce 2002, pp. 147–9

- ↑ New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade War Diary 8 and 9 November 1917 AWM4-35-1-31

- ↑ Hughes 2004, p. 80

- ↑ Preston 1921, p. 59

- 1 2 3 4 Grainger 2006, p. 157

- 1 2 3 Preston 1921, pp. 59–60

- 1 2 3 4 Powles 1922, p. 144

- 1 2 3 Wavell 1968, pp. 149–50

- ↑ Bruce 2002, p. 147

- ↑ Hughes 2004, pp. 81–2

- ↑ Keogh 1955, p. 168

- ↑ Preston 1921, p. 61

- ↑ Hamilton 1996, p. 80

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 663

- ↑ Keogh 1955, p. 163

- 1 2 Carver 2003, p. 218

- ↑ Falls 1930, pp. 138–9

- ↑ Keogh 1955, pp. 167–8

- ↑ Grainger 2006, p. 161

- ↑ Bruce 2002, p. 148

- ↑ Grainger 2006, pp. 160 & 163

- 1 2 3 Falls 1930, p. 144

- ↑ Preston 1921, pp. 61–2

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 143

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 4th LHB War Diary AWM4, 10/4/11

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Preston 1921, p. 66

- 1 2 3 Bruce 2002, pp. 148–9

- ↑ Preston 1921, pp. 58–9

- ↑ Falls 1930, pp. 146–7

- 1 2 Grainger 2006, p. 160

- 1 2 3 Gullett 1939, p. 460

- 1 2 3 4 3rd LHB War Diary AWM4, 10/3/34

- ↑ Hamilton 1996, pp. 80 & 82

- ↑ Hughes 2004, pp. 82–3

- 1 2 3 Powles 1922, p. 145

- 1 2 Falls 1930, p. 148

- ↑ Keogh 1955, p. 169

- ↑ Preston 1922, p. 70

- 1 2 Wavell 1968, p. 153

- 1 2 Bruce 2002, p. 149

- 1 2 Grainger 2006, pp. 165–6

- ↑ Keogh 1955, p. 170

- ↑ Preston 1921, p. 76

- 1 2 Wavell 1968, p. 151

- 1 2 Falls 1930, p. 158

- 1 2 3 4 Bruce 2002, p. 150

- 1 2 Falls 1930, pp. 148–9

- 1 2 Preston 1921, pp. 72–3

- 1 2 3 Carver 2003, p.219

- ↑ Grainger 2006, p. 165

- ↑ Grainger 2006, p. 163

- ↑ Falls 1930, pp. 152–4

- ↑ Falls 1930, p.154

- ↑ Grainger 2006, pp. 162–4

- 1 2 Falls 1930, p. 149

- 1 2 3 Grainger 2006, p. 164

- ↑ Falls 1930, pp. 148–150

- ↑ Grainger 2006, pp. 163–4

- ↑ Falls 1930, pp. 150–2

- ↑ Preston 1921, pp. 73–4

- ↑ Falls 1930 pp. 151–2

- ↑ Erickson 2007 pp. 115–6

- ↑ Keogh 1955, pp. 170–1

- ↑ Grainger 2006, pp. 164–5

- ↑ Falls 1930, p.159

- 1 2 3 Keogh 1955, p. 171

- 1 2 Falls 1930, p. 175

- ↑ Grainger 2006, pp. 166–7

- 1 2 Keogh 1955, p. 172

- 1 2 3 Wavell 1968, pp. 153–4

- 1 2 Wavell 1968, p. 155

- ↑ Falls 1930, pp. 160–2

- ↑ Keogh 1955, pp. 171–2

- 1 2 Australian Mounted Division Hqrs Gen. Staff War Diary AWM4, 1/58/5

- ↑ Paget 1994, pp. 191–2

- 1 2 Wavell 1968, pp. 154–5

- ↑ Grainger 2006, pp. 167 & 170

- 1 2 3 Blenkinsop 1925, p. 205

- ↑ Grainger 2006, p. 168

- ↑ Wavell 1968, pp. 153–5

- ↑ Paget 1994, pp. 191–2 & 198

- ↑ "Estate remembers cavalry action". BBC News UK. 11 November 2007. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 Keogh 1955, p. 175

- ↑ Bruce 2002, p. 151

- ↑ Falls 1930, p. 164

- ↑ Grainger 2006, pp. 161 & 170

- ↑ 12th LH War Diary AWM4, 10/17/10

- ↑ Falls 1930, p. 174

- ↑ Headquarters Australian Mounted Divisional Train War Diary AWM4, 25/20/5

- ↑ Grainger 2006, pp. 172–3

- ↑ Falls 1930, pp. 177–8

- ↑ Kinloch 2007, p. 219

- ↑ Powles 1922, pp. 145–6

- ↑ Falls 1930, p. 176

- ↑ Powles 1922, pp. 153–4

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol.2 Part I, p. 217

- ↑ Bruce 2002, pp. 152–3

- 1 2 Wavell 1968, p. 156

- ↑ Bruce 2002, pp. 151–2

- ↑ Bruce 2002, p. 152

- ↑ Powles 1922, p. 155

- ↑ Keogh 1955, pp. 175 & 178

- ↑ Carver 2003, p. 222

- ↑ Downes 1938 pp. 666–8

- ↑ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 pp. 189–91

References

- "3rd Light Horse Brigade. War Diary. (archive)". First World War Diaries – AWM4, Sub-class 10/3: AWM4, 10/3/34. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. November 1917. Archived from the original (PDF facsimile of manuscript and typescript) on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- "4th Light Horse Brigade. War Diary. (archive)" (PDF facsimile of manuscript and typescript). First World War Diaries – AWM4, Sub-class 10/4: AWM4, 10/4/11. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. November 1917. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- "12th Light Horse Regiment. War Diary. (archive)". First World War Diaries – AWM4, Sub-class 10/17: AWM4, 10/17/10. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. November 1917. Archived from the original (PDF facsimile of manuscript and typescript) on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- "New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade Headquarters War Diary". First World War Diaries AWM4, 35-1-31. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. November 1917. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- "General Staff, Headquarters Australian Mounted Division. War Diary. (archive)" (PDF facsimile of manuscript and typescript). First World War Diaries – AWM4, Sub-class 1/58: AWM4, 1/58/5. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. November 1917. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- "Headquarters Australian Mounted Divisional Train. War Diary. (archive)" (PDF facsimile of manuscript and typescript). First World War Diaries – AWM4, Sub-class 25/20: AWM4, 25/20/5. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. October–November 1917. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- The Official Names of the Battles and Other Engagements Fought by the Military Forces of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–1919, and the Third Afghan War, 1919: Report of the Battles Nomenclature Committee as Approved by The Army Council Presented to Parliament by Command of His Majesty. London: Government Printer. 1922. OCLC 29078007.

- Blenkinsop, Layton John; Rainey, John Wakefield, eds. (1925). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents Veterinary Services. London: H.M. Stationers. OCLC 460717714.

- Bruce, Anthony (2002). The Last Crusade: The Palestine Campaign in the First World War. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5432-2.

- Carver, Michael, Field Marshal Lord (2003). The National Army Museum Book of The Turkish Front 1914–1918: The Campaigns at Gallipoli, in Mesopotamia and in Palestine. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-283-07347-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Downes, Rupert M. (1938). "The Campaign in Sinai and Palestine". In Butler, Arthur Graham (ed.). Gallipoli, Palestine and New Guinea. Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918. Vol. I Part II (2nd ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 547–780. OCLC 220879097.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. No. 201 Contributions in Military Studies. Westport Connecticut: Greenwood Press. OCLC 43481698.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2007). John Gooch; Brian Holden Reid (eds.). Ottoman Army Effectiveness in World War I: A Comparative Study. Cass: Military History and Policy. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96456-9.

- Falls, Cyril; MacMunn, G.; Beck, A.F. (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from June 1917 to the end of the War. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. Part 1. London: H.M. Stationery Office. OCLC 644354483.

- Grainger, John D. (2006). The Battle for Palestine, 1917. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-263-8.

- Gullett, H.S. (1941). The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. VII. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 220900153.

- Hamilton, Patrick M. (1996). Riders of Destiny: The 4th Australian Light Horse Field Ambulance 1917–18: An Autobiography and History. Gardenvale, Melbourne: Mostly Unsung Military History. ISBN 978-1-876179-01-4.

- Hughes, Matthew, ed. (2004). Allenby in Palestine: The Middle East Correspondence of Field Marshal Viscount Allenby June 1917 – October 1919. Army Records Society. Vol. 22. Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3841-9.

- Keogh, E. G.; Joan Graham (1955). Suez to Aleppo. Melbourne: Directorate of Military Training by Wilkie & Co. OCLC 220029983.

- Kinloch, Terry (2007). Devils on Horses: In the Words of the Anzacs in the Middle East, 1916–19. Auckland: Exisle Publishing. OCLC 191258258.

- Moore, A. Briscoe (1920). The Mounted Riflemen in Sinai & Palestine: The Story of New Zealand's Crusaders. Christchurch: Whitcombe & Tombs. OCLC 561949575.

- Paget, G. C. H. V. Marquess of Anglesey (1994). Egypt, Palestine and Syria 1914 to 1919. A History of the British Cavalry 1816–1919. Vol. V. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-395-9.

- Powles, C. Guy; A. Wilkie (1922). The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine. Official History New Zealand's Effort in the Great War. Vol. III. Auckland: Whitcombe & Tombs. OCLC 2959465.

- Preston, R. M. P. (1921). The Desert Mounted Corps: An Account of the Cavalry Operations in Palestine and Syria 1917–1918. London: Constable & Co. OCLC 3900439.

- Wavell, Field Marshal Earl (1968) [1933]. "The Palestine Campaigns". In Sheppard, Eric William (ed.). A Short History of the British Army (4th ed.). London: Constable & Co. OCLC 35621223.

External links

- Baker, Chris. "British Divisions of 1914–1918". The Long Long Trail. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011.