Belize | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Sub umbra floreo (Latin) "Under the shade I flourish" | |

| Anthem: "Land of the Free" | |

| |

_-_BLZ_-_UNOCHA.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital | Belmopan 17°15′N 88°46′W / 17.250°N 88.767°W |

| Largest city | Belize City 17°29′N 88°11′W / 17.483°N 88.183°W |

| Official languages | English |

| Vernacular language | Belizean Creole |

| Regional and minority languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2020)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Belizean |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Dame Froyla Tzalam | |

| Johnny Briceño | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| January 1964 | |

• Independence | 21 September 1981 |

| Area | |

• Total | 22,966 km2 (8,867 sq mi)[4][5] (147th) |

• Water (%) | 0.8 |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 441,471[6] (168th) |

• Density | 17.79/km2 (46.1/sq mi) (169th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2013) | 53.1[8] high |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 123rd |

| Currency | Belize dollar (BZD) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST (GMT-6)[10]) |

| Driving side | right |

| ISO 3166 code | BZ |

| Internet TLD | .bz |

Belize (/bɪˈliːz, bɛ-/ ⓘ, bih-LEEZ, beh-; Belize Kriol English: Bileez) is a country on the north-eastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a water boundary with Honduras to the southeast. It has an area of 22,970 square kilometres (8,867 sq mi) and a population of 441,471 (2022).[6] Its mainland is about 290 km (180 mi) long and 110 km (68 mi) wide. It is the least populated and least densely populated country in Central America. Its population growth rate of 1.87% per year (2018 estimate) is the second-highest in the region and one of the highest in the Western Hemisphere. Its capital is Belmopan, and its largest city is the namesake city of Belize City. Belize is often thought of as a Caribbean country in Central America because it has a history similar to that of English-speaking Caribbean nations. Belize's institutions and official language reflect its history as a British colony.

The Maya civilization spread into the area of Belize between 1500 BC and AD 300 and flourished until about 1200.[11] European contact began in 1502-04 when Christopher Columbus sailed along the Gulf of Honduras.[12] European exploration was begun by English settlers in 1638. Spain and Britain both laid claim to the land until Britain defeated the Spanish in the Battle of St. George's Caye (1798).[13] In 1840 it became a British colony known as British Honduras, and a Crown colony in 1862. Belize achieved its independence from the United Kingdom on 21 September 1981.[14] It is the only mainland Central American country which is a Commonwealth realm, with King Charles III as its monarch and head of state, represented by a governor-general.[15]

Belize has a diverse society composed of many cultures and languages. It is the only Central American country where English is the official language, while Belizean Creole is the most widely spoken dialect. Spanish is the second-most-commonly-spoken language, followed by the Mayan languages, German dialects, and Garifuna. Over half the population is multilingual, due to the diverse linguistic backgrounds of the population. It is known for its September Celebrations, its extensive coral reefs, and punta music.[16][17]

Belize's abundance of terrestrial and marine species and its diversity of ecosystems give it a key place in the globally significant Mesoamerican Biological Corridor.[18] It is considered a Central American and Caribbean nation with strong ties to both the American and Caribbean regions.[19] It is a member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), and the Central American Integration System (SICA), the only country to hold full membership in all three regional organizations.

Name

The earliest known record of the name "Belize" appears in the journal of the Dominican priest Fray José Delgado, dating to 1677.[20] Delgado recorded the names of three major rivers that he crossed while travelling north along the Caribbean coast: Rio Soyte, Rio Kibum, and Rio Balis. The names of these waterways, which correspond to the Sittee River, Sibun River, and Belize River, were provided to Delgado by his translator.[20] It has been proposed that Delgado's "Balis" was actually the Mayan word belix (or beliz), meaning "muddy water",[20] although no such Mayan word actually exists.[21][lower-alpha 2] More recently, it has been proposed that the name comes from the Mayan phrase "bel Itza", meaning "the way to Itza".[21]

In the 1820s, the Creole elite of Belize invented the legend that the toponym Belize derived from the Spanish pronunciation of the name of a Scottish buccaneer, Peter Wallace, who established a settlement at the mouth of the Belize River in 1638.[24] There is no proof that buccaneers settled in this area and the very existence of Wallace is considered a myth.[20][21] Writers and historians have suggested several other possible etymologies, including postulated French and African origins.[20]

History

Early history

The Maya civilization emerged at least three millennia ago in the lowland area of the Yucatán Peninsula and the highlands to the south, in the area of present-day southeastern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and western Honduras. Many aspects of this culture persist in the area, despite nearly 500 years of European domination. Prior to about 2500 BC, some hunting and foraging bands settled in small farming villages; they domesticated crops such as corn, beans, squash, and chili peppers.

A profusion of languages and subcultures developed within the Maya core culture. Between about 2500 BC and 250 AD, the basic institutions of Maya civilization emerged.[11]

Maya civilization

The Maya civilization spread across the territory of present-day Belize around 1500 BC, and flourished until about 900 AD. The recorded history of the middle and southern regions focuses on Caracol, an urban political centre that may have supported over 140,000 people.[25][26] North of the Maya Mountains, the most important political centre was Lamanai.[27] In the late Classic Era of Maya civilization (600–1000 AD), an estimated 400,000 to 1,000,000 people inhabited the area of present-day Belize.[11][28]

When Spanish explorers arrived in the 16th century, the area of present-day Belize included at least three distinct Maya territories:[29]

- Chetumal province, which encompassed the area around Corozal Bay

- Dzuluinicob province, which encompassed the area between the lower New River and the Sibun River, west to Tipu[30][31]

- a southern territory controlled by the Manche Ch'ol Maya, encompassing the area between the Monkey River and the Sarstoon River.

Early colonial period (1506–1862)

Spanish conquistadors explored the land and declared it part of the Spanish Empire, but they failed to settle the territory because of its lack of resources and the hostile tribes of the Yucatán.

English pirates sporadically visited the coast of what is now Belize, seeking a sheltered region from which they could attack Spanish ships (see English settlement in Belize) and cut logwood (Haematoxylum campechianum) trees. The first British permanent settlement was founded around 1716, in what became the Belize District,[32] and during the 18th century, established a system using enslaved Africans to cut logwood trees. This yielded a valuable fixing agent for clothing dyes,[33] and was one of the first ways to achieve a fast black before the advent of artificial dyes. The Spanish granted the British settlers the right to occupy the area and cut logwood in exchange for their help suppressing piracy.[11]

The British first appointed a superintendent over the Belize area in 1786. Before then the British government had not recognized the settlement as a colony for fear of provoking a Spanish attack. The delay in government oversight allowed the settlers to establish their own laws and forms of government. During this period, a few successful settlers gained control of the local legislature, known as the Public Meeting, as well as of most of the settlement's land and timber.

Throughout the 18th century, the Spanish attacked Belize every time war broke out with Britain. The Battle of St. George's Caye was the last of such military engagements, in 1798, between a Spanish fleet and a force of Baymen and their slaves. From 3 to 5 September, the Spaniards tried to force their way through Montego Caye shoal, but were blocked by defenders. Spain's last attempt occurred on 10 September, when the Baymen repelled the Spanish fleet in a short engagement with no known casualties on either side. The anniversary of the battle has been declared a national holiday in Belize and is celebrated to commemorate the "first Belizeans" and the defence of their territory taken from the Spanish empire.[34]

As part of the British Empire (1862–1981)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

In the early 19th century, the British sought to reform the settlers, threatening to suspend the Public Meeting unless it observed the government's instructions to eliminate slavery outright. After a generation of wrangling, slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833.[35] As a result of their enslaved Africans' abilities in the work of mahogany extraction, owners in British Honduras were compensated at £53.69 per enslaved African on average, the highest amount paid in any British territory. This was a form of reparation that was not given to the enslaved Africans at the time, nor since.[32]

The end of slavery did little to change the formerly enslaved Africans' working conditions if they stayed at their trade. A series of institutions restricted the ability of emancipated African individuals to buy land, in a debt-peonage system. Former "extra special" mahogany or logwood cutters undergirded the early ascription of the capacities (and consequently the limitations) of people of African descent in the colony. Because a small elite controlled the settlement's land and commerce, formerly enslaved Africans had little choice but to continue to work in timber cutting.[32]

In 1836, after the emancipation of Central America from Spanish rule, the British claimed the right to administer the region. In 1862, the United Kingdom formally declared it a British Crown Colony, subordinate to Jamaica, and named it British Honduras.[36] Since 1854, the richest inhabitants elected an assembly of notables by censal vote, which was replaced by a legislative council appointed by the British monarchy.[37]

As a colony, Belize began to attract British investors. Among the British firms that dominated the colony in the late 19th century was the Belize Estate and Produce Company, which eventually acquired half of all privately held land and eventually eliminated peonage. Belize Estate's influence accounts in part for the colony's reliance on the mahogany trade throughout the rest of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

The Great Depression of the 1930s caused a near-collapse of the colony's economy as British demand for timber plummeted. The effects of widespread unemployment were worsened by a devastating hurricane that struck the colony in 1931. Perceptions of the government's relief effort as inadequate were aggravated by its refusal to legalize labour unions or introduce a minimum wage. Economic conditions improved during World War II, as many Belizean men entered the armed forces or otherwise contributed to the war effort.

Following the war, the colony's economy stagnated. Britain's decision to devalue the British Honduras dollar in 1949 worsened economic conditions and led to the creation of the People's Committee, which demanded independence. The People's Committee's successor, the People's United Party (PUP), sought constitutional reforms that expanded voting rights to all adults. The first election under universal suffrage was held in 1954 and was decisively won by the PUP, beginning a three-decade period in which the PUP dominated the country's politics. Pro-independence activist George Cadle Price became PUP's leader in 1956 and the effective head of government in 1961, a post he would hold under various titles until 1984.

Progress toward independence was hampered by a Guatemalan claim to sovereignty over Belizean territory. In 1964 Britain granted British Honduras self-government under a new constitution. On 1 June 1973, British Honduras was officially renamed Belize.[38]

Independent Belize (since 1981)

Belize was granted independence on 21 September 1981. Guatemala refused to recognize the new nation because of its longstanding territorial dispute, claiming that Belize belonged to Guatemala. After independence about 1,500 British troops remained in Belize to deter any possible Guatemalan incursions.[39]

With George Cadle Price at the helm, the PUP won all national elections until 1984. In that election, the first national election after independence, the PUP was defeated by the United Democratic Party (UDP). UDP leader Manuel Esquivel replaced Price as prime minister, with Price himself unexpectedly losing his own House seat to a UDP challenger. The PUP under Price returned to power after elections in 1989. The following year the United Kingdom announced that it would end its military involvement in Belize, and the RAF Harrier detachment was withdrawn the same year, having remained stationed in the country continuously since its deployment had become permanent there in 1980. British soldiers were withdrawn in 1994, but the United Kingdom left behind a military training unit to assist with the newly created Belize Defence Force.

The UDP regained power in the 1993 national election, and Esquivel became prime minister for a second time. Soon afterwards, Esquivel announced the suspension of a pact reached with Guatemala during Price's tenure, claiming Price had made too many concessions to gain Guatemalan recognition. The pact may have curtailed the 130-year-old border dispute between the two countries. Border tensions continued into the early 2000s, although the two countries cooperated in other areas.

In 1996, the Belize Barrier Reef, one of the Western Hemisphere's most pristine ecosystems, was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The PUP won a landslide victory in the 1998 national elections, and PUP leader Said Musa was sworn in as prime minister. In the 2003 elections the PUP maintained its majority, and Musa continued as prime minister. He pledged to improve conditions in the underdeveloped and largely inaccessible southern part of Belize.

In 2005, Belize was the site of unrest caused by discontent with the PUP government, including tax increases in the national budget. On 8 February 2008, Dean Barrow was sworn in as prime minister after his UDP won a landslide victory in general elections. Barrow and the UDP were re-elected in 2012 with a considerably smaller majority. Barrow led the UDP to a third consecutive general election victory in November 2015, increasing the party's number of seats from 17 to 19. He said the election would be his last as party leader and preparations are under way for the party to elect his successor.

On 11 November 2020, the People's United Party (PUP), led by Johnny Briceño, defeated the United Democratic Party (UDP) for the first time since 2003, having won 26 seats out of 31 to form the new government of Belize. Briceño took office as Prime Minister on 12 November.[40]

Government and politics

Belize is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. The structure of government is based on the British parliamentary system, and the legal system is modelled on the common law of England. The head of state is Charles III, who is the king of Belize. He lives in the United Kingdom, and is represented in Belize by the governor-general. Executive authority is exercised by the cabinet, which advises the governor-general and is led by the prime minister, who is head of government. Cabinet ministers are members of the majority political party in parliament and usually hold elected seats within it concurrent with their cabinet positions.

The bicameral National Assembly of Belize comprises a House of Representatives and a Senate. The 31 members of the House are popularly elected to a maximum five-year term and introduce legislation affecting the development of Belize. The governor-general appoints the 12 members of the Senate, with a Senate president selected by the members. The Senate is responsible for debating and approving bills passed by the House.

Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Parliament of Belize. Constitutional safeguards include freedom of speech, press, worship, movement, and association. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.[41]

Members of the independent judiciary are appointed. The judicial system includes local magistrates grouped under the Magistrates' Court, which hears less serious cases. The Supreme Court (chief justice) hears murder and similarly serious cases, and the Court of Appeal hears appeals from convicted individuals seeking to have their sentences overturned. Defendants may, under certain circumstances, appeal their cases to the Caribbean Court of Justice.

Political culture

In 1935, elections were reinstated, but only 1.8 percent of the population was eligible to vote. In 1954, women won the right to vote.[37]

Since 1974, the party system in Belize has been dominated by the centre-left People's United Party and the centre-right United Democratic Party, although other small parties took part in all levels of elections in the past. Though none of these small political parties has ever won any significant number of seats or offices, their challenge has been growing over the years.

Foreign relations

Belize is a full participating member of the United Nations; the Commonwealth of Nations; the Organization of American States (OAS); the Central American Integration System (SICA); the Caribbean Community (CARICOM); the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME); the Association of Caribbean States (ACS); and the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), which currently serves as a final court of appeal for only Barbados, Belize, Guyana and Saint Lucia. In 2001 the Caribbean Community heads of government voted on a measure declaring that the region should work towards replacing the UK's Judicial Committee of the Privy Council as final court of appeal with the Caribbean Court of Justice. It is still in the process of acceding to CARICOM treaties including the trade and single market treaties.

Belize is an original member (1995) of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and participates actively in its work. The pact involves the Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM) subgroup of the Group of African, Caribbean, and Pacific states (ACP). CARIFORUM presently the only part of the wider ACP-bloc that has concluded the full regional trade-pact with the European Union.

The British Army Garrison in Belize is used primarily for jungle warfare training, with access to over 13,000 square kilometres (5,000 sq mi) of jungle terrain.[42]

Belize is a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[43]

Armed forces

The Belize Defence Force (BDF) serves as the country's military. The BDF, with the Belize National Coast Guard and the Immigration Department, is a department of the Ministry of Defence and Immigration. In 1997 the regular army numbered over 900, the reserve army 381, the air wing 45 and the maritime wing 36, amounting to an overall strength of approximately 1,400.[44] In 2005, the maritime wing became part of the Belizean Coast Guard.[45] In 2012, the Belizean government spent about $17 million on the military, constituting 1.08% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP).[46] After Belize achieved independence in 1981 the United Kingdom maintained a deterrent force (British Forces Belize) in the country to protect it from invasion by Guatemala (see Guatemalan claim to Belizean territory). During the 1980s this included a battalion and No. 1417 Flight RAF of Harriers. The main British force left in 1994, three years after Guatemala recognized Belizean independence, but the United Kingdom maintained a training presence via the British Army Training and Support Unit Belize (BATSUB) and 25 Flight AAC until 2011 when the last British Forces left Ladyville Barracks, with the exception of seconded advisers.[44]

Administrative divisions

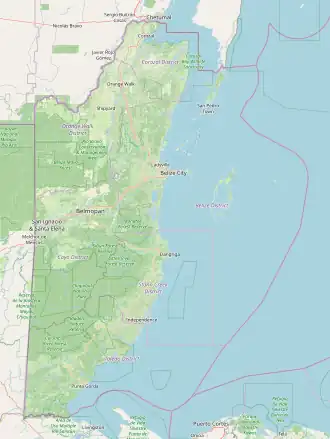

Belize is divided into six districts.

| District | Capital | Area[5] | Population (2019)[47] |

Population (2010)[5] |

Change | Population density (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | Belize City | 4,310 km2 (1,663 sq mi) | 124,096 | 95,292 | +30.2% | 28.8/km2 (74.6/sq mi) |

| Cayo | San Ignacio | 5,200 km2 (2,006 sq mi) | 99,118 | 75,046 | +32.1% | 19.1/km2 (49.4/sq mi) |

| Corozal | Corozal Town | 1,860 km2 (718 sq mi) | 49,446 | 41,061 | +20.4% | 26.6/km2 (68.9/sq mi) |

| Orange Walk | Orange Walk Town | 4,600 km2 (1,790 sq mi) | 52,550 | 45,946 | +14.4% | 11.3/km2 (29.4/sq mi) |

| Stann Creek | Dangriga | 2,550 km2 (986 sq mi) | 44,720 | 34,324 | +30.3% | 17.5/km2 (45.4/sq mi) |

| Toledo | Punta Gorda | 4,410 km2 (1,704 sq mi) | 38,557 | 30,785 | +25.2% | 8.7/km2 (22.6/sq mi) |

These districts are further divided into 31 constituencies. Local government in Belize comprises four types of local authorities: city councils, town councils, village councils and community councils. The two city councils (Belize City and Belmopan) and seven town councils cover the urban population of the country, while village and community councils cover the rural population.[48]

Guatemalan territorial dispute

Throughout Belize's history, Guatemala has claimed sovereignty over all or part of Belizean territory. This claim is occasionally reflected in maps drawn by Guatemala's government, showing Belize as Guatemala's twenty-third department.[49][lower-alpha 3]

The Guatemalan territorial claim involves approximately 53% of Belize's mainland, which includes significant portions of four districts: Belize, Cayo, Stann Creek, and Toledo.[51] Roughly 43% of the country's population (≈154,949 Belizeans) reside in this region.[52]

As of 2020, the border dispute with Guatemala remains unresolved and contentious.[49][53][54] Guatemala's claim to Belizean territory rests, in part, on Clause VII of the Anglo-Guatemalan Treaty of 1859, which obligated the British to build a road between Belize City and Guatemala. At various times, the issue has required mediation by the United Kingdom, Caribbean Community heads of government, the Organization of American States (OAS), Mexico, and the United States. On 15 April 2018, Guatemala's government held a referendum to determine if the country should take its territorial claim on Belize to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to settle the long-standing issue. Guatemalans voted 95%[55] yes on the matter.[56] A similar referendum was to be held in Belize on 10 April 2019, but a court ruling led to its postponement.[57] The referendum was held on 8 May 2019, and 55.4% of voters opted to send the matter to the ICJ.[58]

Both countries submitted requests to the ICJ (in 2018 and 2019, respectively) and the ICJ ordered Guatemala's initial brief be submitted by December 2020 and Belize's response by 2022.[59]

Indigenous land claims

Belize backed the United Nations (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, which established legal land rights to indigenous groups.[60] Other court cases have affirmed these rights like the Supreme Court of Belize's 2013 decision to uphold its ruling in 2010 that acknowledges customary land titles as communal land for indigenous peoples.[61] Another such case is the Caribbean Court of Justice's (CCJ) 2015 order on the Belizean government, which stipulated that the country develop a land registry to classify and exercise traditional governance over Mayan lands. Despite these rulings, Belize has made little progress to support the land rights of indigenous communities; for instance, in the two years after the CCJ's decision, Belize's government failed to launch the Mayan land registry, prompting the group to take action into its own hands.[62][63]

The exact ramifications of these cases need to be examined. As of 2017, Belize still struggles to recognize indigenous populations and their respective rights. According to the 50-page voluntary national report Belize created on its progress toward the UN's 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, indigenous groups are not factored into the country's indicators whatsoever.[64] Belize's Maya population is only mentioned once in the entirety of the report.[65]

Geography

Belize is on the Caribbean coast of northern Central America. It shares a border on the north with the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, on the west with the Guatemalan department of Petén, and on the south with the Guatemalan department of Izabal. To the east in the Caribbean Sea, the second-longest barrier reef in the world flanks much of the 386 kilometres (240 mi) of predominantly marshy coastline.[66] The area of the country totals 22,960 square kilometres (8,865 sq mi), an area slightly larger than El Salvador, Israel, New Jersey, or Wales. The many lagoons along the coasts and in the northern interior reduces the actual land area to 21,400 square kilometres (8,263 sq mi). It is the only Central American country with no Pacific coastline.

Belize is shaped roughly like a rhombus that extends about 280 kilometres (174 mi) north-south and about 100 kilometres (62 mi) east-west, with a total land boundary length of 516 kilometres (321 mi). The undulating courses of two rivers, the Hondo and the Sarstoon River, define much of the course of the country's northern and southern boundaries. The western border follows no natural features and runs north–south through lowland forest and highland plateau.

The north of Belize consists mostly of flat, swampy coastal plains, in places heavily forested. The flora is highly diverse considering the small geographical area. The south contains the low mountain range of the Maya Mountains. The highest point in Belize is Doyle's Delight at 1,124 m (3,688 ft).[67]

Belize's rugged geography has also made the country's coastline and jungle attractive to drug smugglers, who use the country as a gateway into Mexico.[68] In 2011, the United States added Belize to the list of nations considered major drug producers or transit countries for narcotics.[69]

Environment preservation and biodiversity

Belize has a rich variety of wildlife because of its position between North and South America and a wide range of climates and habitats for plant and animal life.[70] Belize's low human population and approximately 22,970 square kilometres (8,867 sq mi) of undistributed land make for an ideal home for the more than 5,000 species of plants and hundreds of species of animals, including armadillos, snakes, and monkeys.[71]

The Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary is a nature reserve in south-central Belize established to protect the forests, fauna, and watersheds of an approximately 400 km2 (150 sq mi) area of the eastern slopes of the Maya Mountains. The reserve was founded in 1990 as the first wilderness sanctuary for the jaguar and is regarded by one author as the premier site for jaguar preservation in the world.[72]

Vegetation and flora

While over 60% of Belize's land surface is covered by lush forest,[73] some 20% of the country's land is covered by cultivated land (agriculture) and human settlements.[74] Belize had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.15/10, ranking it 85th globally out of 172 countries.[75] Savanna, scrubland and wetland constitute the remainder of Belize's land cover. Important mangrove ecosystems are also represented across Belize's landscape.[76][77] Four terrestrial ecoregions lie within the country's borders – the Petén–Veracruz moist forests, Belizian pine forests, Belizean Coast mangroves, and Belizean Reef mangroves.[78] As a part of the globally significant Mesoamerican Biological Corridor that stretches from southern Mexico to Panama, Belize's biodiversity – both marine and terrestrial – is rich, with abundant flora and fauna.

Belize is also a leader in protecting biodiversity and natural resources. According to the World Database on Protected Areas, 37% of Belize's land territory falls under some form of official protection, giving Belize one of the most extensive systems of terrestrial protected areas in the Americas.[79] By contrast, Costa Rica only has 27% of its land territory protected.[80]

Around 13.6% of Belize's territorial waters, which contain the Belize Barrier Reef, are also protected.[81] The Belize Barrier Reef is a UNESCO-recognized World Heritage Site and is the second-largest barrier reef in the world, behind Australia's Great Barrier Reef.

A remote sensing study conducted by the Water Center for the Humid Tropics of Latin America and the Caribbean (CATHALAC) and NASA, in collaboration with the Forest Department and the Land Information Centre (LIC) of the government of Belize's Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment (MNRE), and published in August 2010 revealed that Belize's forest cover in early 2010 was approximately 62.7%, down from 75.9% in late 1980.[73] A similar study by Belize Tropical Forest Studies and Conservation International revealed similar trends in terms of Belize's forest cover.[82] Both studies indicate that each year, 0.6% of Belize's forest cover is lost, translating to the clearing of an average of 10,050 hectares (24,835 acres) each year. The USAID-supported SERVIR study by CATHALAC, NASA, and the MNRE also showed that Belize's protected areas have been extremely effective in protecting the country's forests. While only some 6.4% of forests inside of legally declared protected areas were cleared between 1980 and 2010, over a quarter of forests outside of protected areas were lost between 1980 and 2010.

As a country with a relatively high forest cover and a low deforestation rate, Belize has significant potential for participation in initiatives such as REDD. Significantly, the SERVIR study on Belize's deforestation[73] was also recognized by the Group on Earth Observations (GEO), of which Belize is a member nation.[83]

Natural resources and energy

Belize is known to have a number of economically important minerals, but none in quantities large enough to warrant mining. These minerals include dolomite, barite (source of barium), bauxite (source of aluminium), cassiterite (source of tin), and gold. In 1990 limestone, used in road construction, was the only mineral resource exploited for domestic or export use.

In 2006, the cultivation of newly discovered crude oil in the town of Spanish Lookout has presented new prospects and problems for this developing nation.[84]

Access to biocapacity in Belize is much higher than world average. In 2016, Belize had 3.8 global hectares[85] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much more than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[86] In 2016 Belize used 5.4 global hectares of biocapacity per person – their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use more biocapacity than Belize contains. As a result, Belize is running a biocapacity deficit.[85]

Belize Barrier Reef

The Belize Barrier Reef is a series of coral reefs straddling the coast of Belize, roughly 300 metres (980 ft) offshore in the north and 40 kilometres (25 mi) in the south within the country limits. The Belize Barrier Reef is a 300-kilometre-long (190 mi) section of the 900-kilometre-long (560 mi) Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, which is continuous from Cancún on the northeast tip of the Yucatán Peninsula through the Riviera Maya up to Honduras making it one of the largest coral reef systems in the world.

It is the top tourist destination in Belize, popular for scuba diving and snorkelling, and attracting almost half of its 260,000 visitors. It is also vital to its fishing industry.[87] In 1842 Charles Darwin described it as "the most remarkable reef in the West Indies".

The Belize Barrier Reef was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996 due to its vulnerability and the fact that it contains important natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biodiversity.[88]

Species

The Belize Barrier Reef is home to a large diversity of plants and animals, and is one of the most diverse ecosystems of the world:

- 70 hard coral species

- 36 soft coral species

- 500 species of fish

- hundreds of invertebrate species

With ~90% of the reef still yet to be researched, some estimate that only 10% of all species have been discovered.[89]

Conservation

Belize became the first country in the world to completely ban bottom trawling in December 2010.[90][91] In December 2015, Belize banned offshore oil drilling within 1 km (0.6 mi) of the Barrier Reef and all of its seven World Heritage Sites.[92]

Despite these protective measures, the reef remains under threat from oceanic pollution as well as uncontrolled tourism, shipping, and fishing. Other threats include hurricanes, along with global warming and the resulting increase in ocean temperatures,[93] which causes coral bleaching. It is claimed by scientists that over 40% of Belize's coral reef has been damaged since 1998.[87]

Climate

Belize has a tropical climate with pronounced wet and dry seasons, although there are significant variations in weather patterns by region. Temperatures vary according to elevation, proximity to the coast, and the moderating effects of the northeast trade winds off the Caribbean. Average temperatures in the coastal regions range from 24 °C (75.2 °F) in January to 27 °C (80.6 °F) in July. Temperatures are slightly higher inland, except for the southern highland plateaus, such as the Mountain Pine Ridge, where it is noticeably cooler year round. Overall, the seasons are marked more by differences in humidity and rainfall than in temperature.

Average rainfall varies considerably, from 1,350 millimetres (53 in) in the north and west to over 4,500 millimetres (180 in) in the extreme south. Seasonal differences in rainfall are greatest in the northern and central regions of the country where, between January and April or May, less than 100 millimetres (3.9 in) of rainfall per month. The dry season is shorter in the south, normally only lasting from February to April. A shorter, less rainy period, known locally as the "little dry", usually occurs in late July or August, after the onset of the rainy season.

Hurricanes have played key—and devastating—roles in Belizean history. In 1931, an unnamed hurricane destroyed over two-thirds of the buildings in Belize City and killed more than 1,000 people. In 1955, Hurricane Janet levelled the northern town of Corozal. Only six years later, Hurricane Hattie struck the central coastal area of the country, with winds in excess of 300 km/h (185 mph) and 4 m (13 ft) storm tides. The devastation of Belize City for the second time in thirty years prompted the relocation of the capital some 80 kilometres (50 mi) inland to the planned city of Belmopan.

In 1978, Hurricane Greta caused more than US$25 million in damage along the southern coast. In 2000, Hurricane Keith, the wettest tropical cyclone in the nation's record, stalled, and hit the nation as a Category 4 storm on 1 October, causing 19 deaths and at least $280 million in damage. Soon after, on 9 October 2001, Hurricane Iris made landfall at Monkey River Town as a 235 km/h (145 mph) Category 4 storm. The storm demolished most of the homes in the village, and destroyed the banana crop. In 2007, Hurricane Dean made landfall as a Category 5 storm only 40 km (25 mi) north of the Belize–Mexico border. Dean caused extensive damage in northern Belize.

In 2010, Belize was directly affected by the Category 2 Hurricane Richard, which made landfall approximately 32 kilometres (20 mi) south-southeast of Belize City at around 00:45 UTC on 25 October 2010.[94] The storm moved inland towards Belmopan, causing estimated damage of BZ$33.8 million ($17.4 million 2010 USD), primarily from damage to crops and housing.[95] The most recent hurricane to make landfall in Belize was Hurricane Lisa in 2022.

Economy

Belize has a small, mostly private enterprise economy that is based primarily on agriculture, agro-based industry, and merchandising, with tourism and construction recently assuming greater importance.[84] The country is also a producer of industrial minerals,[96] crude oil, and petroleum. As of 2017, oil production was 320 m3/d (2,000 bbl/d).[97] In agriculture, sugar, like in colonial times, remains the chief crop, accounting for nearly half of exports, while the banana industry is the largest employer.[84] In 2007 Belize became the world's third largest exporter of papaya.[98]

The government of Belize faces important challenges to economic stability. Rapid action to improve tax collection has been promised, but a lack of progress in reining in spending could bring the exchange rate under pressure. The tourist and construction sectors strengthened in early 1999, leading to a preliminary estimate of revived growth at four percent. Infrastructure remains a major economic development challenge;[99] Belize has the region's most expensive electricity. Trade is important and the major trading partners are the United States, Mexico, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and CARICOM.[99]

Belize has four commercial bank groups, of which the largest and oldest is Belize Bank. The other three banks are Heritage Bank, Atlantic Bank, and Scotiabank (Belize). A robust complex of credit unions began in the 1940s under the leadership of Marion M. Ganey, S.J.[100]

Because of its location on the coast of Central America, Belize is a popular destination for vacationers and for many North American drug traffickers. The Belize currency is pegged to the U.S. dollar and banks in Belize offer non-residents the ability to establish accounts, so drug traffickers and money launderers are attracted to banks in Belize. As a result, the United States Department of State has recently named Belize one of the world's "major money laundering countries".[101]

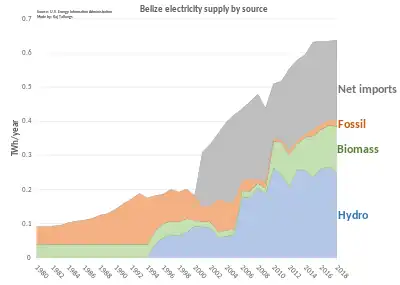

Industrial infrastructure

The largest integrated electric utility and the principal distributor in Belize is Belize Electricity Limited. BEL was approximately 70% owned by Fortis Inc., a Canadian investor-owned distribution utility. Fortis took over the management of BEL in 1999, at the invitation of the government of Belize in an attempt to mitigate prior financial problems with the locally managed utility. In addition to its regulated investment in BEL, Fortis owns Belize Electric Company Limited (BECOL), a non-regulated hydroelectric generation business that operates three hydroelectric generating facilities on the Macal River.

On 14 June 2011, the government of Belize nationalized the ownership interest of Fortis Inc. in Belize Electricity Ltd. The utility encountered serious financial problems after the country's Public Utilities Commission (PUC) in 2008 "disallowed the recovery of previously incurred fuel and purchased power costs in customer rates and set customer rates at a level that does not allow BEL to earn a fair and reasonable return", Fortis said in a June 2011 statement.[102] BEL appealed this judgement to the Court of Appeal, with a hearing expected in 2012. In May 2011, the Supreme Court of Belize granted BEL's application to prevent the PUC from taking any enforcement actions pending the appeal. The Belize Chamber of Commerce and Industry issued a statement saying the government had acted in haste and expressed concern over the message it sent to investors.

In August 2009, the government of Belize nationalized Belize Telemedia Limited (BTL), which now competes directly with Speednet. As a result of the nationalization process, the interconnection agreements are again subject to negotiations. Both BTL and Speednet sell basic telephone services, national and international calls, prepaid services, cellular services via GSM 1900 megahertz (MHz) and 4G LTE respectively, international cellular roaming, fixed wireless, fibre-to-the-home internet service, and national and international data networks.[103]

Tourism

A combination of natural factors – climate, the Belize Barrier Reef, over 450 offshore Cays (islands), excellent fishing, safe waters for boating, scuba diving, snorkelling and freediving, numerous rivers for rafting, and kayaking, various jungle and wildlife reserves of fauna and flora, for hiking, bird watching, and helicopter touring, as well as many Maya sites – support the thriving tourism and ecotourism industry.

Development costs are high, but the government of Belize has made tourism its second development priority after agriculture. In 2012, tourist arrivals totalled 917,869 (with about 584,683 from the United States) and tourist receipts amounted to over $1.3 billion.[104]

After COVID-19 struck tourism, Belize became the first country in the Caribbean to allow vaccinated travelers to visit without a COVID-19 test.[105]

Demographics

Belize's population is estimated to be 441,471 in 2022.[6] Belize's total fertility rate in 2009 was 3.6 children per woman. Its birth rate was 22.9 births/1,000 population (2018 estimate), and the death rate was 4.2 deaths/1,000 population (2018 estimate).[2] A substantial ethnic-demographic shift has been occurring since 1980 when the Creole/Mestizo ratio shifted from 58/38 to currently 26/53, due to many Creoles moving to the US and a rising Mestizo birth rate and migration from El Salvador.[106]

Ethnic groups

The Maya

The Maya are thought to have been in Belize and the Yucatán region since the second millennium BCE. Many died in conflicts between constantly warring tribes or by catching disease from invading Europeans. Three Maya groups now inhabit the country: The Yucatec (who came from Yucatán, Mexico, to escape the savage Caste War of the 1840s), the Mopan (indigenous to Belize but were forced out to Guatemala by the British for raiding settlements; they returned to Belize to evade enslavement by the Guatemalans in the 19th century), and Q'eqchi' (also fled from slavery in Guatemala in the 19th century).[107] The latter groups are chiefly found in the Toledo District. The Maya speak their native languages and Spanish, and are also often fluent in English and Belizean Creole.

Creoles

Belizean Creoles are primarily mixed-raced descendants of West and Central Africans who were brought to the British Honduras (present-day Belize along the Bay of Honduras) as well as the English and Scottish log cutters, known as the Baymen who trafficked them.[108][109] Over the years they have also intermarried with Miskito from Nicaragua, Jamaicans and other Caribbean people, Mestizos, Europeans, Garifunas, Mayas, and Chinese and Indians. The latter were brought to Belize as indentured laborers. Majority of Creoles trace their ancestry to several of the aforementioned groups. For all intents and purposes, Creole is an ethnic and linguistic denomination. Some natives, even with blonde hair and blue eyes, may call themselves Creoles.[110]

Belize Creole or Kriol developed during the time of slavery, and historically was only spoken by former enslaved Africans. It became an integral part of the Belizean identity, and is now spoken by about 45% of Belizeans.[111][110] Belizean Creole is derived mainly from English. Its substrate languages are the Native American language Miskito, and the various West African and Bantu languages, native languages of the enslaved Africans. Creoles are found all over Belize, but predominantly in urban areas such as Belize City, coastal towns and villages, and in the Belize River Valley.[112]

Garinagu

The Garinagu (singular Garifuna), at around 4.5% of the population, are a mix of West/Central African, Arawak, and Island Carib ancestry. Though they were captives removed from their homelands, these people were never documented as slaves. The two prevailing theories are that, in 1635, they were either the survivors of two recorded shipwrecks or somehow took over the ship they came on.[113]

Throughout history they have been incorrectly labelled as Black Caribs. When the British took over Saint Vincent and the Grenadines after the Treaty of Paris in 1763, they were opposed by French settlers and their Garinagu allies. The Garinagu eventually surrendered to the British in 1796. The British separated the more African-looking Garifunas from the more indigenous-looking ones. 5,000 Garinagu were exiled from the Grenadine island of Baliceaux. About 2,500 of them survived the voyage to Roatán, an island off the coast of Honduras. The Garifuna language belongs to the Arawakan language family, but has a large number of loanwords from Carib languages and from English.

Because Roatán was too small and infertile to support their population, the Garinagu petitioned the Spanish authorities of Honduras to be allowed to settle on the mainland coast. The Spanish employed them as soldiers, and they spread along the Caribbean coast of Central America. The Garinagu settled in Seine Bight, Punta Gorda and Punta Negra, Belize, by way of Honduras as early as 1802. In Belize, 19 November 1832 is the date officially recognized as "Garifuna Settlement Day" in Dangriga.[114]

According to one genetic study, their ancestry is on average 76% Sub Saharan African, 20% Arawak/Island Carib and 4% European.[113]

Mestizos

The Mestizo culture are people of mixed Spanish and Yucatec Maya descent. They originally came to Belize in 1847, to escape the Caste War, which occurred when thousands of Mayas rose against the state in Yucatán and massacred over one-third of the population. The surviving others fled across the borders into British territory. The Mestizos are found everywhere in Belize but most make their homes in the northern districts of Corozal and Orange Walk. Some other Hispanics came from Latin and Central America like El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. The Mestizos along with Latin Americans are the largest ethnic group in Belize and make up approximately half of the population. The Mestizo towns centre on a main square, and social life focuses on the Hispanic and Catholic Church traditions and customs. Spanish is the main language of most Mestizos and Hispanic descendants, but many speak English and Belizean Creole fluently.[115] Due to the influences of Belizean Creole and English, many Mestizos speak what is known as "Kitchen Spanish".[116] The mixture of Yucatec Mestizo and Yucatec[117] Maya foods like tamales, escabeche, chirmole, relleno, and empanadas came from their Mexican side and corn tortillas were handed down by their Mayan side. Music comes mainly from the marimba, but they also play and sing with the guitar. Dances performed at village fiestas include the Hog-Head, Zapateados, the Mestizada, Paso Doble and many more.

German-speaking Mennonites

The majority of the Mennonite population comprises so-called Russian Mennonites of German descent who settled in the Russian Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries. Most Russian Mennonites live in Mennonite settlements like Spanish Lookout, Shipyard, Little Belize, and Blue Creek. These Mennonites speak Plautdietsch (a Low German dialect) in everyday life, but use mostly Standard German for reading (the Bible) and writing. The Plautdietsch-speaking Mennonites came mostly from Mexico in the years after 1958 and they are trilingual with proficiency in Spanish. There are also some mainly Pennsylvania Dutch-speaking Old Order Mennonites who came from the United States and Canada in the late 1960s. They live primarily in Upper Barton Creek and associated settlements. These Mennonites attracted people from different Anabaptist backgrounds who formed a new community. They look quite similar to Old Order Amish, but are different from them.

Other groups

The remaining 5% or so of the population consist of a mix of Indians, Chinese, Whites from the United Kingdom, United States and Canada, and many other foreign groups brought to assist the country's development. During the 1860s, a large influx of East Indians who spent brief periods in Jamaica and American Civil War veterans from Louisiana and other Southern states established Confederate settlements in British Honduras and introduced commercial sugar cane production to the colony, establishing 11 settlements in the interior. The 20th century saw the arrival of more Asian settlers from Mainland China, India, Syria and Lebanon. Said Musa, the son of an immigrant from Palestine, was the Prime Minister of Belize from 1998 to 2008. Central American immigrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua and expatriate Americans and Africans also began to settle in the country.[114] 6,000 Mexicans live in Belize.[119]

Emigration, immigration, and demographic shifts

Creoles and other ethnic groups are emigrating mostly to the United States, but also to the United Kingdom and other developed nations for better opportunities. Based on the latest US Census, the number of Belizeans in the United States is approximately 160,000 (including 70,000 legal residents and naturalized citizens), consisting mainly of Creoles and Garinagu.[120]

Because of conflicts in neighbouring Central American nations, Hispanics or Latin American refugees from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras have fled to Belize in significant numbers during the 1980s, and have been significantly adding to Belize's Hispanic population. These two events have been changing the demographics of the nation for the last 30 years.[121]

Languages

English is the official language of Belize. This stems from the country being a former British colony. Belize is the only country in Central America with English as the official language. Also, English is the primary language of public education, government and most media outlets. Although English is widely used, Belizean Creole is spoken in all situations whether informal, formal, social or interethnic dialogue, even in meetings of the House of Representatives.

When a Creole language exists alongside its lexifier language, as is the case in Belize, a continuum forms between the Creole and the lexifier language. It is therefore difficult to substantiate or differentiate the number of Belize Creole speakers compared to English speakers. Creole might best be described as the lingua franca of the nation.[122]

Approximately 52.9% of Belizeans self-identify as Mestizo, Latino, or Hispanic. When Belize was a British colony, Spanish was banned in schools, but today it is widely spoken. "Kitchen Spanish" is an intermediate form of Spanish mixed with Belize Creole, spoken in the northern towns such as Corozal and San Pedro.[116]

Over half the population is multilingual.[123] Being a small, multiethnic state, surrounded by Spanish-speaking nations, the economic and social benefits from multilingualism are high.[124]

Belize is also home to three Maya languages: Q'eqchi', Mopan (an endangered language), and Yucatec Maya.[125][126][127] Approximately 16,100 people speak the Arawakan-based Garifuna language,[128] and 6,900 Mennonites in Belize speak mainly Plautdietsch while a minority of Mennonites speak Pennsylvania Dutch.[129]

Largest cities

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Belize City  San Ignacio |

1 | Belize City | Belize District | 57,169 |  Belmopan  Orange Walk Town | ||||

| 2 | San Ignacio | Cayo District | 17,878 | ||||||

| 3 | Belmopan | Cayo District | 13,939 | ||||||

| 4 | Orange Walk Town | Orange Walk District | 13,708 | ||||||

| 5 | San Pedro Town | Belize District | 11,767 | ||||||

| 6 | Corozal Town | Corozal District | 10,287 | ||||||

| 7 | Dangriga | Stann Creek District | 9,593 | ||||||

| 8 | Benque Viejo del Carmen | Cayo District | 6,140 | ||||||

| 9 | Ladyville | Belize District | 5,458 | ||||||

| 10 | Punta Gorda | Toledo District | 5,351 | ||||||

Religion

According to the 2010 census,[111] 40.1% of Belizeans are Roman Catholics, 31.8% are Protestants (8.4% Pentecostal; 5.4% Adventist; 4.7% Anglican; 3.7% Mennonite; 3.6% Baptist; 2.9% Methodist; 2.8% Nazarene), 1.7% are Jehovah's Witnesses, 10.3% adhere to other religions (Maya religion, Garifuna religion, Obeah and Myalism, and minorities of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims, Baháʼís, Rastafarians and other) and 15.5% profess to be irreligious.

According to PROLADES, Belize was 64.6% Roman Catholic, 27.8% Protestant, 7.6% Other in 1971.[130] Until the late 1990s, Belize was a Roman Catholic majority country. Catholics formed 57% of the population in 1991, and dropped to 49% in 2000. The percentage of Roman Catholics in the population has been decreasing in the past few decades due to the growth of Protestant churches, other religions and non-religious people.[131]

In addition to Catholics, there has always been a large accompanying Protestant minority. It was brought by British, German, and other settlers to the British colony of British Honduras. From the beginning, it was largely Anglican and Mennonite in nature. The Protestant community in Belize experienced a large Pentecostal and Seventh-Day Adventist influx tied to the recent spread of various Evangelical Protestant denominations throughout Latin America. Geographically speaking, German Mennonites live mostly in the rural districts of Cayo and Orange Walk.

The Greek Orthodox Church has a presence in Santa Elena.[132]

The Association of Religion Data Archives estimates there were 7,776 Baháʼís in Belize in 2005, or 2.5% of the national population. Their estimates suggest this is the highest proportion of Baháʼís in any country.[133] Their data also states that the Baháʼí Faith is the second most common religion in Belize, following Christianity.[134] Hinduism is followed by most Indian immigrants. Sikhs were the first Indian immigrants to Belize (not counting indentured workers), and the former Chief Justice of Belize George Singh was the son of a Sikh immigrant,[135][136] there was also a Sikh cabinet minister. Muslims claim that there have been Muslims in Belize since the 16th century having been brought over from Africa as slaves, but there are no sources for that claim.[137] The Muslim population of today started in the 1980s. Muslims numbered 243 in 2000 and 577 in 2010 according to the official statistics.[138] and comprise 0.16 percent of the population. A mosque is at the Islamic Mission of Belize (IMB), also known as the Muslim Community of Belize. Another mosque, Masjid Al-Falah, officially opened in 2008 in Belize City.[139]

Health

Belize has a high prevalence of communicable diseases such as respiratory diseases and intestinal illnesses.[140]

Education

A number of kindergartens, secondary, and tertiary schools in Belize provide education for students—mostly funded by the government. Belize has about a dozen tertiary level institutions, the most prominent of which is the University of Belize, which evolved out of the University College of Belize founded in 1986. Before that St. John's College, founded in 1877, dominated the tertiary education field. The Open Campus of the University of the West Indies has a site in Belize.[141] It also has campuses in Barbados, Trinidad, and Jamaica. The government of Belize contributes financially to the UWI.

Education in Belize is compulsory between the ages of 6 and 14 years. As of 2010, the literacy rate in Belize was estimated at 79.7%,[111] one of the lowest in the Western Hemisphere.

The educational policy is currently following the "Education Sector Strategy 2011–2016", which sets three objectives for the years to come: Improving access, quality, and governance of the education system by providing technical and vocational education and training.[142]

Crime

Belize has moderate rates of violent crime.[143] The majority of violence in Belize stems from gang activity, which includes trafficking of drugs and persons, protecting drug smuggling routes, and securing territory for drug dealing.[144]

In 2019, 102 murders were recorded in Belize, giving the country a homicide rate of 24 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, lower than the neighbouring countries of Mexico and Honduras, but higher than Guatemala and El Salvador.[145] Belize District (containing Belize City) had the most murders by far compared to all the other districts. In 2019, 58% of the murders occurred in the Belize District.[146] The violence in Belize City (especially the southern part of the city) is largely due to gang warfare.[143]

In 2015, there were 40 reported cases of rape, 214 robberies, 742 burglaries, and 1027 cases of theft.[147]

The Belize Police Department has implemented many protective measures in hopes of decreasing the high number of crimes. These measures include adding more patrols to "hot spots" in Belize City, obtaining more resources to deal with the predicament, creating the "Do the Right Thing for Youths at Risk" program, creating the Crime Information Hotline, creating the Yabra Citizen Development Committee, an organization that helps youth, and other initiatives.[144] In 2011, the government established a truce among many major gangs, lowering the murder rate.[143]

Social structure

Belize's social structure is marked by enduring differences in the distribution of wealth, power, and prestige. Because of the small size of Belize's population and the intimate scale of social relations, the social distance between the rich and the poor, while significant, is nowhere as vast as in other Caribbean and Central American societies, such as Jamaica and El Salvador. Belize lacks the violent class and racial conflict that has figured so prominently in the social life of its Central American neighbours.[148]

Political and economic power remain vested in the hands of the local elite. The sizeable middle group is composed of peoples of different ethnic backgrounds. This middle group does not constitute a unified social class, but rather a number of middle-class and working-class groups, loosely oriented around shared dispositions toward education, cultural respectability, and possibilities for upward social mobility. These beliefs, and the social practices they engender, help distinguish the middle group from the grass roots majority of the Belizean people.[148]

Women

In 2021, the World Economic Forum ranked Belize 90th out of 156 countries in its Global Gender Gap Report. Of all the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Belize ranked fourth from last. It ranked higher in the categories of "economic participation and opportunity" and "health and survival", but very low in "political empowerment".[149] In 2019, the UN gave Belize a Gender Inequality Index score of 0.415, ranking it 97th out of 162 countries.[150]

As of 2019, 49.9% of women in Belize participate in the workforce, compared to 80.6% of men.[150] 11.1% of the seats in Belize's National Assembly are filled by women.[150]

Culture

In Belizean folklore, there are the legends of Lang Bobi Suzi, La Llorona, La Sucia, Tata Duende, Anansi, Xtabay, Sisimite and the cadejo.

Most of the public holidays in Belize are traditional Commonwealth and Christian holidays, although some are specific to Belizean culture such as Garifuna Settlement Day and Heroes and Benefactors' Day, formerly Baron Bliss Day.[151] In addition, the month of September is considered a special time of national celebration called September Celebrations with a whole month of activities on a special events calendar. Besides Independence Day and St. George's Caye Day, Belizeans also celebrate Carnival during September, which typically includes several events spread across multiple days, with the main event being the Carnival Road March, usually held the Saturday before 10 September. In some areas of Belize, it is celebrated at the traditional time before Lent (in February).[152]

Cuisine

Belizean cuisine is an amalgamation of all ethnicities in the nation, and their respectively wide variety of foods. It might best be described as both similar to Mexican/Central American cuisine and Jamaican/Anglo-Caribbean cuisine but very different from these areas as well, with Belizean touches and innovation which have been handed down by generations. All immigrant communities add to the diversity of Belizean food, including the Indian and Chinese communities.

The Belizean diet can be both very modern and traditional. There are no rules. Breakfast typically consists of bread, flour tortillas, or fry jacks (deep fried dough pieces) that are often homemade. Fry jacks are eaten with various cheeses, "fry" beans, various forms of eggs or cereal, along with powdered milk, coffee, or tea. Tacos made from corn or flour tortillas and meat pies can also be consumed for a hearty breakfast from a street vendor. Midday meals are the main meals for Belizeans, usually called "dinner". They vary, from foods such as rice and beans with or without coconut milk, tamales, "panades" (fried maize shells with beans or fish), meat pies, escabeche (onion soup), chimole (soup), caldo, stewed chicken, and garnaches (fried tortillas with beans, cheese, and sauce) to various constituted dinners featuring some type of rice and beans, meat and salad, or coleslaw. Fried "fry" chicken is another common course.

In rural areas, meals are typically simpler than in cities. The Maya use maize, beans, or squash for most meals, and the Garifuna are fond of seafood, cassava (particularly made into cassava bread or ereba), and vegetables. The nation abounds with restaurants and fast food establishments that are fairly affordable. Local fruits are quite common, but raw vegetables from the markets less so. Mealtime is a communion for families and schools and some businesses close at midday for lunch, reopening later in the afternoon.

Music

In recent years, Latin music, including reggaeton and banda, has experienced a surge in popularity in Belize, alongside the traditional genres of punta and brukdown. This growing trend reflects the influence of neighboring Latin American countries and the cultural connections that exist within the region. The rise in popularity of Latin music in Belize demonstrates the vibrant and diverse musical landscape of the country, showcasing the ability of music to transcend borders and bring people together.

Punta is distinctly Caribbean, and is sometimes said to be ready for international popularization like similarly descended styles (reggae, calypso, merengue).

Brukdown is a modern style of Belizean music related to calypso. It evolved out of the music and dance of loggers, especially a form called buru. Reggae, dance hall, and soca imported from Trinidad, Jamaica, and the rest of the West Indies, rap, hip-hop, heavy metal, and rock music from the United States, are also popular among the youth of Belize.

Sports

The major sports in Belize are football, basketball, volleyball and cycling, with smaller followings of boat racing, athletics, softball, cricket and rugby. Fishing is also popular in coastal areas of Belize.

The Cross Country Cycling Classic, also known as the "cross country" race or the Holy Saturday Cross Country Cycling Classic, is considered one of the most important Belize sports events. This one-day sports event is meant for amateur cyclists but has also gained worldwide popularity. The history of Cross Country Cycling Classic in Belize dates back to the period when Monrad Metzgen picked up the idea from a small village on the Northern Highway (now Phillip Goldson Highway). The people from this village used to cover long distances on their bicycles to attend the weekly game of cricket. He improvised on this observation by creating a sporting event on the difficult terrain of the Western Highway, which was then poorly built.

Another major annual sporting event in Belize is the La Ruta Maya Belize River Challenge, a 4-day canoe marathon held each year in March. The race runs from San Ignacio to Belize City, a distance of 290 kilometres (180 mi).[153]

On Easter day, citizens of Dangriga participate in a yearly fishing tournament. First, second, and third prize are awarded based on a scoring combination of size, species, and number. The tournament is broadcast over local radio stations, and prize money is awarded to the winners.

The Belize national basketball team is the only national team that has achieved major victories internationally. The team won the 1998 CARICOM Men's Basketball Championship, held at the Civic Centre in Belize City, and subsequently participated in the 1999 Centrobasquet Tournament in Havana. The national team finished seventh of eight teams after winning only 1 game despite playing close all the way. In a return engagement at the 2000 CARICOM championship in Barbados, Belize placed fourth. Shortly thereafter, Belize moved to the Central American region and won the Central American Games championship in 2001.

The team has failed to duplicate this success, most recently finishing with a 2–4 record in the 2006 COCABA championship. The team finished second in the 2009 COCABA tournament in Cancun, Mexico where it went 3–0 in group play. Belize won its opening match in the Centrobasquet Tournament, 2010, defeating Trinidad and Tobago, but lost badly to Mexico in a rematch of the COCABA final. A tough win over Cuba set Belize in position to advance, but they fell to Puerto Rico in their final match and failed to qualify.

Simone Biles, the winner of four gold medals in the 2016 Rio Summer Olympics is a dual citizen of the United States and of Belize,[154] which she considers her second home.[155] Biles is of Belizean-American descent.[156]

National symbols

The national flower of Belize is the black orchid (Prosthechea cochleata, also known as Encyclia cochleata). The national tree is the mahogany tree (Swietenia macrophylla), which inspired the national motto Sub Umbra Floreo, which means "Under the shade I flourish". The national ground-dwelling animal is the Baird's tapir and the national bird is the keel-billed toucan (Ramphastos sulphuratus).[157]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Percentages add up to more than 100% because respondents were able to identify more than one ethnic origin.

- ↑ "Mud" is rendered as lukʼ in the Yucatecan languages, while "water" is rendered as jaʼ, ja, or ha.[21][22][23]

- ↑ In April 2019, a media outlet showed video of Guatemalan president Jimmy Morales showing students how to draw Guatemala's map to include all of Belize, reflecting his country's claim.[50]

References

- 1 2 "Belize Population and Housing Census 2010: Country Report" (PDF). Statistical Institute of Belize. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- 1 2 "Belize § People and Society". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 14 August 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- ↑ "Religions in Belize | PEW-GRF". Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ↑ "Belize § Geography". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 14 August 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- 1 2 3 Belize Population and Housing Census 2010: Country Report (PDF) (Report). Statistical Institute of Belize. 2013. p. 70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Postcensal estimates by age group and sex, 2010 - 2022" (XLSX). Statistical Institute of Belize. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Belize)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ↑ "Income Gini coefficient". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ↑ Belize (11 March 1947). "Definition of Time Act" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2020. Unusually, the legislation states that standard time is six hours later than Greenwich mean time.

- 1 2 3 4 Bolland, Nigel (1993). "Belize: Historical Setting" (PDF). In Tim Merrill (ed.). Guyana and Belize: Country Studies. Library of Congress Federal Research Division. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Byrd Downey, Cristopher (22 May 2012). Stede Bonnet: Charleston's Gentleman Pirate. The History Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1609495404. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Woodard, Colin. "A Blackbeard mystery solved". Republic of Pirates Blog. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Belize | History, Capital, Language, Map, Flag, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ↑ "Belize - British Honduras - Central America - Nations Online Project". www.nationsonline.org. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ↑ "Reid between the lines". Belize Times. 27 January 2012. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Ryan, Jennifer (1995). "The Garifuna and Creole culture of Belize explosion of punta rock". In Will Straw; Stacey Johnson; Rebecca Sullivan; Paul Friedlander; Gary Kennedy (eds.). Popular Music: Style and Identity. Centre for Research on Canadian Cultural Industries and Institutions. pp. 243–248. ISBN 978-0771704598.

- ↑ "Ecosystem Mapping.zip". Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "CARICOM – Member Country Profile – BELIZE". www.caricom.org. CARICOM. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Twigg, Alan (2006). Understanding Belize: A Historical Guide. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing. pp. 9–10, 38–45. ISBN 978-1550173253.

- 1 2 3 4 Restall, Matthew (21 February 2019). "Creating "Belize": The Mapping and Naming History of a Liminal Locale". Terrae Incognitae. 51 (1): 5–35. doi:10.1080/00822884.2019.1573962. S2CID 134010746.

- ↑ Dienhart, John M. (1989). The Mayan Languages: A Comparative Vocabulary. Denmark: Odense University Press. pp. 443–444, 708. ISBN 8774927221.

- ↑ Hofling, Charles Andrew (2011). Mopan Maya - Spanish - English dictionary. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. pp. 631, 662. ISBN 9781607810292.

- ↑ "British Honduras". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12. New York: The Britannica Publishing Company. 1892. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ↑ Houston, Stephen D.; Robertson, J; Stuart, D (2000). "The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions". Current Anthropology. 41 (3): 321–356. doi:10.1086/300142. ISSN 0011-3204. PMID 10768879. S2CID 741601.

- ↑ "History: Site Overview". Caracol Archaeological Project. Department of Anthropology, University of Central Florida. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ Scarborough, Vernon L.; Clark, John E. (2007). The Political Economy of Ancient Mesoamerica: Transformations During the Formative and Classic Periods. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0826342980.

- ↑ Shoman, Assad (1995). Thirteen chapters of a history of Belize. Belize City, Belize: Angelus Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-9768052193.

- ↑ Shoman, Assad (1995). Thirteen chapters of a history of Belize. Belize City, Belize: Angelus Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-9768052193.

- ↑ "Belizean studies maya resistance". Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ↑ Jones, Grant D. (1989). Maya Resistance to Spanish Rule: Time and History on a Colonial Frontier. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. p. 98. hdl:2027/mdp.39015015491791. ISBN 9780826311610. OCLC 20012099.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Melissa A. (October 2003). "The Making of Race and Place in Nineteenth-Century British Honduras" (PDF). Environmental History. 8 (4): 598–617. doi:10.2307/3985885. hdl:11214/203. JSTOR 3985885. S2CID 144161630.

- ↑ Hofenk de Graff, Judith H. (2004). The Colourful Past: Origins, Chemistry and Identification of Natural Dyestuffs. London: Archetype Books. p. 235. ISBN 978-1873132135.

- ↑ Swift, Keith (1 September 2009). "St. George's Caye Declared a Historic Site". News 7 Belize.

- ↑ "3° & 4° Gulielmi IV, cap. LXXIII An Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies; for promoting the Industry of the manumitted Slaves; and for compensating the Persons hitherto entitled to the Services of such Slaves". Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ Greenspan (2007). Frommer's Belize. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 279–. ISBN 978-0-471-92261-2. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- 1 2 "L'Amérique centrale – Une Amérique indienne et latine" (PDF). clio.fr (in French). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ "Belize". CARICOM. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ↑ Merrill, Tim, ed. (1992). "Relations with Britain". Belize: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress.

- ↑ Sanchez, Jose (12 November 2020). "Belize elects opposition leader to succeed retiring leader". Reuters India. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ↑ "Belize 1981 (rev. 2001)". Constitute. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ "New Lease of Life for British Army Base in Belize". Forces TV. 7 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015.

- ↑ "Latin American and Caribbean State Parties to the Rome Statute, International Criminal Court. Retrieved 10 July 2021".

- 1 2 Phillips, Dion E. (2002). "The Military of Belize". Archived from the original on 11 December 2012.

- ↑ "Channel 5 Belize" (28 November 2005),"Belizean Coast Guard hits the high seas". Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ↑ "Belize § Military and Security". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 14 August 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- ↑ "Belize: Districts, Towns & Villages - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de.

- ↑ "Local Government". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2016.. Government of Belize. belize.gov.bz

- 1 2 "Belize § Transnational Issues". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 14 August 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- ↑ Staff (10 April 2019). "Guatemalan President teaches students to draw Guatemalan map with Belize included". San Ignacio, Belize: Breaking Belize News. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ↑ "SATIIM launches Maya lands registry to celebrate UN Indigenous Peoples day". Breaking Belize News-The Leading Online News Source of Belize. 9 August 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ↑ "Historic Legal Victory for Indigenous Peoples in Belize | Rights + Resources". Rights + Resources. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ↑ "Belize-Guatemala border tensions rise over shooting – BBC News". BBC News. 22 April 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ "ACP-EU summit 2000". Hartford-hwp.com. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "Why Belize Is Likely to Prevail in Its Territorial Dispute With Guatemala". www.worldpoliticsreview.com. 23 May 2019.

- ↑ "Belize to hold a referendum on Guatemala territorial dispute - Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ↑ Staff (10 April 2019). "ICJ Referendum postponed until further notice". San Ignacio, Belize: Breaking Belize News. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ↑ Sanchez, Jose (9 May 2019). "Belizeans vote to ask U.N. court to settle Guatemala border dispute". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- ↑ "Extension of the time-limits for the filing of the initial pleadings" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 24 April 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Full Participation of Belize's Indigenous People is Crucial to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ↑ "Historic Legal Victory for Indigenous Peoples in Belize | Rights + Resources". Rights + Resources. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ↑ "SATIIM launches Maya lands registry to celebrate UN Indigenous Peoples day". Breaking Belize News-The Leading Online News Source of Belize. 9 August 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ↑ "Historic Legal Victory for Indigenous Peoples in Belize | Rights + Resources". Rights + Resources. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ↑ "Belize's Voluntary National Review For the Sustainable Development Goals 2017" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ↑ "The Full Participation of Belize's Indigenous People is Crucial to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ↑ "Move to Belize Guide". Belize Travel Guide. March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012.

- ↑ "BERDS Topography". Biodiversity.bz. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "Small And Isolated, Belize Attracts Drug Traffickers". NPR. 29 October 2011.

- ↑ "Mexican drug cartels reach into tiny Belize". The Washington Post. 28 September 2011.

- ↑ Moon Handbooks (2006). "Know Belize – Flora & Fauna". CentralAmerica.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ↑ Jayawardena, Chandana (2002). Tourism and Hospitality Education and Training in the Caribbean. University of the West Indies Press. pp. 165–176. ISBN 978-9766401191.

- ↑ Emmons, Katherine M. (1996). Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary. Gays Mills, Wisconsin: Orangutan Press. ISBN 978-0963798220.