| Maya Mountains | |

|---|---|

| Montañas mayas | |

Maya Mountains during clear conditions / 2012 photograph by E. xxx / via Flickr | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Doyle's Delight |

| Elevation | 3,688 ft (1,124 m)1 |

| Coordinates | 16°40′04″N 88°49′59″W / 16.667652361130873°N 88.8331618650507°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 70 mi (110 km) northeast1 |

| Width | 40 mi (64 km) southeast |

| Area | 1,970 sq mi (5,100 km2)2 |

| Geography | |

| |

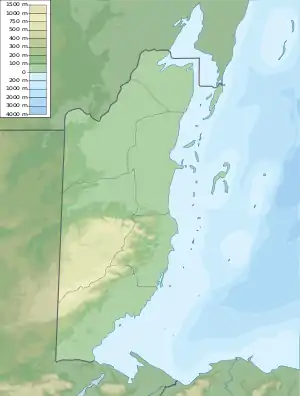

| Countries | southwestern Belize and northeastern Guatemala |

| Districts | Cayo, Stann Creek, Toledo, Peten |

| Range coordinates | 16°53′58″N 88°40′18″W / 16.899443741204585°N 88.67161109755861°W |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Palaeozoic–Cenozoic3 |

| Type of rock |

|

| Volcanic arc/belt | Bladen Formation3 |

| Last eruption | c. 410 Ma3 |

| 1 Per EB 2017, para. 1 / 2 Per Briggs et al. 2013, para. 2 / 3 Per Martens 2009, cap. 4 | |

The Maya Mountains are a mountain range located in Belize and eastern Guatemala, in Central America.[note 1]

Etymology

The Maya Mountains were known as the Cockscomb or Coxcomb Mountains to Baymen and later Belizeans at least until the mid-20th century.[1][2][3][4][note 2] Their current appellation is thought to be in honour of the Mayan civilisation.[5]

Geography

Physical

Peaks

The range's highest peaks are Doyle's Delight at 3,688 feet (1,124 m) and Victoria Peak at 3,680 feet (1,120 m).[5]

Rivers

Nine streams with a Strahler order greater than 1 flow from the Mountains into the Caribbean Sea, namely, five tributaries of the Belize River, two tributaries of the Monkey River, and the Sittee River and Boom Creek.[6]

Karst

Prominent karstic features within the Mountains include the Chiquibul Spring and Cave System, the Vaca Plateau, the Southern and Northern Boundary Faults, and possibly an aquifer contiguous with that of the Yucatán Peninsula.[7][8][note 3]

Plutons

The Mountains 'are the only source of igneous and metamorphic materials' in Belize.[9] These are exposed in three plutons, i.e. Mountain Pine Ridge, Hummingbird Ridge, and the Cockscomb Basin.[10] It has been recently suggested that the former was mined by stonemasons at Pacbitun for the manufacture and trade of stonetools, e.g. manos and metates.[11]

Climate

Precipitation decreases from 98 inches (2,500 mm) per annum in the northwestern extreme of the Mountains to 59 inches (1,500 mm) per annum in its southeastern extreme.[12]

Human

Parks

Much of the Mountains is in protected areas spanning seventeen parks, reserves, sanctuaries, or monuments in southern Belize and northern Guatemala.[13][14]

| WDPA ID | Name | Type | District | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3306 | Chiquibul | forest reserve | Cayo | – |

| 3314 | Columbia River | forest reserve | Toledo | – |

| 3311 | Deep River | forest reserve | Toledo | – |

| 28850 | Maya Mountain | forest reserve | Stann Creek | – |

| 3305 | Mountain Pine Ridge | forest reserve | Cayo | – |

| 3307 | Sibun River | forest reserve | Cayo | – |

| 12229 | Sittee River | forest reserve | Stann Creek | – |

| 116297 | Vaca | forest reserve | Cayo | – |

| 301932 | Noj Kaax Me'en Eligio Panti | national park | Cayo | – |

| 20230 | Chiquibul | national park | Cayo | – |

| 12241 | Bladen | nature reserve | Toledo | – |

| 10579 | Cockscomb Basin | wildlife sanctuary | Stann Creek | – |

| 20229 | Caracol | archaeological reserve | Cayo | – |

| 301918 | Victoria Peak | natural monument | Stann Creek | – |

| 30614 | Montañas Mayas Chiquibul | nature reserve | Peten | – |

| 30618 | San Román | nature reserve | Peten | – |

| 902858 | Yaxhá-Nakum-Naranjo | national park | Peten | – |

Threats

Unauthorised farming and resource extraction by Guatemalans have been identified as a significant threats to Belize's protected areas bordering Peten.[18] For instance, in 2008 an estimated 1,000–1,500 xateros i.e. fishtail palm foragers were operating in the region, and by 2011 some 13,500–20,000 acres had been cleared for various agricultural activities, thereby severing the ecologically important contiguity of Belizean forests to the Guatemalan Selva Maya.[19] Furthermore, unlicensed interlopers often hunt for sustenance during their extended incursions, leading to worrying declines in wildlife populations, such as that of the white-lipped peccary, which has been extirpated from 'was once the species' primary stronghold in Belize [i.e. Chiquibul].'[20] Threats indigenous to Belize have also been identified, however, with demographic pressures deemed the most significant.[21] The recent construction of the hydroelectric Chalillo Dam in the Mountains, for instance, 'sparked international controversy for its widespread ecological effects,' including the inundation of 2,400 acres of forested and riparian ecosystems, and exposure of downstream villages to significant pollutants in 2009 and 2011.[22]

Geology

Maya Mountains | |

|---|---|

Maya Mountains / in 2006 map by French & Schenk / via USGS | |

| Grid position | coordinates = |

| Location | central Belize, northeastern Guatemala |

| Part of | Maya Block |

| Geology |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,470 sq mi (11,600 km2)1 |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 95 mi (153 km)1 |

| • Width | 65 mi (105 km)1 |

| USGS geologic province number | 6125 |

| 1 As per French & Schenk 2004 and French & Schenk 2006 maps. | |

The Mountains and their abutting foothills and plains, considered as a north-easterly trending structural uplift of Palaeozoic bedrock, constitute a geologic or physiographic province in the Maya Block of the North American Plate.[23][24][25] The province is bounded by the seismically inactive Northern and Southern Boundary Faults.[26][27][28][note 5]

History

The Mountains' orogen mainly consists of metamorphosed late Carboniferous to middle Permian volcanic-sedimentary rocks overlying late Silurian granites.[27]

Stratigraphy

Basement

The Mountains' basement is sub-aerially exposed in four extremes of the mountain range.[23][29][30] The exposed portions in the northwestern, northeastern, and southeastern points of the range are predominantly composed of intermediate-to-silicic Palaeozoic plutons, with exposed portions in the southern point of the range predominated by Palaeozoic volcanic rocks.[23][note 6][note 7]

The geologic evolution of the exposed portions of the Mountains' basement has been deemed 'one of the most disputed aspects of Central American geology,' though it has subsequently been suggested that these formed during the late-Neogene to late-Pliocene.[31][32]

Cover

The Mountains' sedimentary cover blankets all of the province's foothills and plains, and all but a few portions of its mountain range.[23][32][30] The cover in the foothills and plains is predominantly composed of Cretacaeous marine strata to the south, west, and north, but this transitions into Quaternary alluvium to the east.[23][note 8] In contrast, the cover in the mountain range is predominated by Palaeozoic strata.[23][note 9]

The Mountains' cover in the mountain range has been recently characterised as an elevated relict landscape, i.e. an area where basement uplift has not been counterbalanced by fluvial erosion.[33]

Formation

Geologic mapping and dating of rocks in the Maya Mountains have 'led to a variety of interpretations and eventually to puzzling discrepancies between reported field relations, age of fossils, and geochronologic data.'[34] An early 1955 study divided the Mountains' sedimentary rocks into Macal and Maya series or formations, but these were subsequently rejected in favour of the single Santa Rosa Group of sedimentary rocks (discovered in Guatemala in 1966).[35] However, this consensus was upended upon the 1996 discovery of deeper granitoids which crystallisation ages 'considerably older' than known post-Devonian ages of Santa Rosa fossils.[36] The presence of pre-Devonian sediments was 'a matter of debate' until 'conclusively demonstrate[d]' in the affirmative in 2009.[37]

| Name | Rocks | Epoch | Age | Unit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maya Block crystalline basement | – | Ediacaran – Cambrian | 560–540 | Ma | cf [note 11] |

| Baldy Unit |

|

Cambrian – Silurian | 517–406 | Ma | cf [note 12] |

| Mountain Pine Ridge Pluton | granite | Ordovician – Silurian | 420–405 | Ma | cf [note 13] |

| Bladen Formation |

|

Silurian – Devonian | 413–400 | Ma | cf [note 14] |

| Macal Formation |

|

Pennsylvanian – Permian | 330–270 | Ma | cf [note 15] |

| Hummingbird–Mullins Pluton | granite | Triassic | 250–220 | Ma | cf [note 16] |

| Cockscomb–Sapote Pluton | granite | Triassic | 240–206 | Ma | cf [note 17] |

| Todos Santos | – | Jurassic – Cretaceous | 175–125 | Ma | cf [note 18] |

| Coban Limestone |

|

Cretaceous – Holocene | 150–0 | Ma | cf [note 19] |

Morphology

Basins

The Mountains are wedged between the easterly to northeasterly trending Corozal and Belize Basins, themselves sub-basins of the Peten–Corozal Basin, which fully encompasses the Mountains.[27][40][note 20]

History

Pre-Columbian

The Mountains are thought to have remained sparsely populated, and culturally and economically isolated, until 600–830 CE, during the Late Classic, when the region experienced major demographic growth, possibly peaking in the 8th century.[41] In c. 830 CE, during the Classic Maya Collapse, most of the Mountains' settlements experienced demographic decline, leading to sparse settlement during the Postclassic.[41]

Columbian

The mountains are mainly made of Paleozoic era granite and sediments. The Maya Mountains and associated foothills contain a number of important Mayan ruins including the sites of Lubaantun, Nim Li Punit, Cahal Pech and Chaa Creek.[42][43]

Conservation

In Belize

The earliest public conservation-like efforts in Belize are thought to have been geared towards regulating mahogany logging, via a 28 October 1817 proclamation vesting unclaimed lands in the Crown.[44][45] The measure quickly proved futile however, as by 17 April 1835 Belize's Superintendent would note that 'no regulation or restriction has prevailed respecting the cutting of Wood or the occupation of Land and thus the mahogany on the extensive Tracts to the Southward of the Sibun and between the Rivers Belize & Hondo above Black Creek has been subjected to great waste and devastation.'[46][45] The next step is thought to have been in 1894, with the passage of the first legislative protections for antiquities in colonial Belize, subsequently strengthened in 1897, 1924, and 1927.[47][48][49][50] Archaeological conservation in Belize progressed quickly with the 1952 appointment of Alexander Hamilton Anderson as First Assistant Secretary to the Governor with responsibility for archaeological activities in the country, and the subsequent 1954 establishment of the Department of Archaeology, with Anderson as its inaugural commissioner or permanent secretary.[51][52][53][note 21] Natural conservation likewise advanced with the 1887 Hooper and 1921 Hummel Reports, the 1922 establishment of a Department of Forestry, with Cornelius Hummel as inaugural conservator or permanent secretary, and the 1924, 1926, 1927, 1935, 1944, and 1945 passages of legislative protections for flora and fauna.[54][55][56][57][45][58][note 22] Significantly, Silk Grass and Mountain Pine Ridge were gazetted as forest reserves in 1920, making these Belize's earliest non-archaeological protected areas.[45][59]

In Guatemala

The earliest conservation efforts in Guatemala are thought to have been the 1921 and 1945 Leyes Forestales, leading to the 1955 establishment of the country's first protected areas, the Atitlán and Rio Dulce National Parks.[60]

Study

Exploration

The earliest known exploratory expedition into the Mountains was led by captains Samuel Harrison and Valentín Delgado in 8 July – 9 August 1787. The captains had been commissioned by the superintendent of colonial Belize, Edward Marcus Despard, and the visiting Spanish commissary, Enrique de Grimarest, to discover the source of the Sibun River, so as to ascertain the limits of the British settlement under the 1786 Convention of London.[61][62][63][64]

Subsequent pioneering explorations were led by Henry Fowler in 1879, C. H. Wilson in 1886, Karl Sapper in 1886–1935, J. Bellamy in 1888, L. H. Ower in 1922–1926, C. G. Dixon in 1950–1955, and J. H. Bateson and I. H. S. Hall in 1969–1970.[65][66][1][67] Sapper's trips have been deemed 'the first geologic expeditions' into the Mountains, while Ower's survey produced what has been called 'the first geological map of the Colony [of British Honduras, including the Mountains].'[65][66][note 23]

See also

- Mountain ranges of Central America

Notes and references

Explanatory footnotes

- ↑ The term Maya Mountains may additionally refer a geologic or physiographic province coincident with the mountain range and its abutting foothills and plains, rather to the mountain range per se, eg as in Andreani & Gloaguen 2016, pp. 76–77. This article employs the geologic sense of the term when appropriate, eg in the 'Geology' section.

- ↑ Mountains called only Cockscomb or variants in Bellamy 1889, Sapper 1896a, Sapper 1899; called both Cockscomb and Maya in USDI 1947 and Dixon 1956; and called only Maya in Dixey 1957, Bateson & Hall 1977. The Cockscomb name survives in various designations, including that of the Cockscomb Range, an east-west spur of the Maya Mountains extending some 10 miles (16 km) (EB 2012, para. 1).

- ↑ The aquifer's existence has been suggested on the basis of karstifiable carbonates and evaporites, contiguous to those of the Peninsula, being present in the western and southern foothills and plains of the Mountains (Goldscheider et al. 2020, p. 1666).

- ↑ WDPA ID is the identifier used in the World Database on Protected Areas in UNEP-WCMC 2022a, sec. 'Belize Protected Areas' and UNEP-WCMC 2022b, sec. 'Guatemala Protected Areas'.

- ↑ Though Bundschuh & Alvarado 2012, pp. 77–79, 80 do not consider the mountain range and surrounding environs to constitute a physiographic province.

- ↑ The southern extreme of the range further includes an exposed portion predominated by intrusive, undivided, intermediate-to-silicic rocks of unknown age (French & Schenk 2004).

- ↑ Martens 2009, pp. 7, 23 give the basement as being sub-aerially exposed in three extremes of the mountain range, with exposed portions mainly composed of Palaeozoic granitic batholiths and stocks. Martens 2009, p. 121 give a more accurate picture of the basement as being exposed in four extremes of the range, with Devonian–Silurian granitoids prevailing in portions in three extremes, and lithic conglomerates, sandstones, and rhyolites prevailing in portions of one extreme.

- ↑ The cover in the western foothills and plains further includes some islands of Quaternary alluvium, Aeocene-to-Palaeocene marine strata, and Jurassic-to-Triassic marine and continental strata (French & Schenk 2004).

- ↑ Martens 2009, p. 7, fig. 1.2 describe the cover over the mountain range as mainly composed of low-grade metasediments and local hornfelses.

- ↑ All units informal as of 2019 (King et al. 2019, p. 222, fn. 1).

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, p. 142, and noted as the 'recognised' basement age of the Maya Block. Though Martens 2009, p. 148 further notes that this age 'seems only valid for the northernmost tip of the [Maya] block.'

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, pp. 123, 137. Lower and upper ages considered uncertain per Martens 2009, p. 123, fig. 4.2. Sandstones mature, in contrast to Macal Formation, per Martens 2009, pp. 124–125. Detrital zircons from sandstone samples dated 1.9–0.5 Ga, with 1.2 and 1.0 Ga ages most prominent, per Martens 2009, pp. 128, 133–134, 136–137, 140–143. Martens 2009, pp. 142–143 suggest the 1.2–1.0 Ga Grenvillian zircons 'could be local to the Maya Block' or neighbouring Oaxaquia microcontinent, while the 1.6–1.5 Ga zircons are 'probably not autochthonous to the Maya Block nor [the] Oaxaquia [microcontinent], inasmuch as no rocks older than ~1.4 Ga have been found on them,' rather suggesting that the latter were 'most likely' sourced from the Rio Negro–Juruena province of the Western Amazonian craton of Gondwana. Zhao et al. 2020, p. 140 further note that 'inherited zircon ages of 1210 Ma from the Maya mountain and 1100 Ma from the Chicxulub granitoids imply that the northern Maya block may [...] have Grenville-aged materials.' Ross et al. 2021, p. 243, fig. 1 further suggest the 0.6–0.5 Ga zircons may have a Pan-African orogeny affinity.

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, pp. 123, 135, Ross et al. 2021, p. 244, and Guzman-Hidalgo et al. 2021, p. 2. Dated 422 – circa 406 Ma in Martens 2009, pp. 126–127. Pluton is mostly two-mica granite, granodiorite, and tonalite containing > 10 percent quartz, per Martens 2009, p. 125, and exhibits relatively high potassium content and large circa 10 millimetres (0.39 in) minerals, per Lewis & Valdez 2015, p. 143.

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, pp. 119, 123 and Ross et al. 2021, p. 244. Lower and upper ages considered uncertain per Martens 2009, p. 123, fig. 4.2. Dated circa 415 – circa 406 Ma in Martens 2009, pp. 135, 136. This Formation is an east-west belt covering over 200 square kilometres (77 sq mi), and consists almost entirely of rhyolitic-dacitic lava flows and tuffs, with some original volcanic features partly preserved (eg autobrecciated lava flows and flow banding), per Martens 2009, p. 126.

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, p. 123. Described as 'regionally equivalent to the Santa Rosa Group of Guatemala' and 'containing fossils similar to those in the Santa Rosa Group' in Martens 2009, pp. 122, 135. Sandstones immature, in contrast to Baldy Unit, per Martens 2009, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, p. 123. Pluton ranges from muscovite quartz-monzonite to biotite granodiorite, with rare garnet xenocrysts, per Martens 2009, p. 125, and exhibits relatively high muscovite-biotite ratio and small circa 5 millimetres (0.20 in) minerals, per Lewis & Valdez 2015, p. 143.

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, p. 123. Dated 235–205 Ma in Martens 2009, p. 126. Dated 237–205 Ma in Ross et al. 2021, p. 244. Pluton is a biotite granodiorite with accessory white mica, per Martens 2009, p. 125, and exhibits relatively high biotite-muscovite ratio and small circa 5 millimetres (0.20 in) minerals, per Lewis & Valdez 2015, p. 143.

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, p. 123. Lower and upper ages considered uncertain per Martens 2009, p. 123, fig. 4.2.

- ↑ Age as per Martens 2009, p. 123.

- ↑ Though Steel & Davidson 2020a, foldout map describe the Mountains as wedged between three basins, ie the Corozal, Belize, and Peten Basins, none of which is noted as a sub-basin of any other.

- ↑ Though establishment of the Department of Archaeology dated 1953 by Vitelli 1983, p. 218 and 1957 by Nichols & Pool 2012, p. 71.

- ↑ Hooper and Hummel Reports in Hooper 1887 and Hummel 1921.

- ↑ For their work output, see Bateson & Hall 1977, Bellamy 1889, Dixon 1956, Fowler 1879, IGS 1975, Ower 1928a, Ower 1928b, Sapper 1896a, Sapper 1896b, Sapper 1898, and Sapper 1899, among other published works.

Short citations

- 1 2 Bellamy 1889, p. 542.

- ↑ Sapper 1899, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Usher 1888, 'Southern District' of map.

- ↑ USDI 1947, pp. 3, 7.

- 1 2 EB 2017, para. 1.

- ↑ Andreani & Gloaguen 2016, p. 91, fig. 16.

- ↑ Goldscheider et al. 2020, pp. 1666–1667.

- ↑ Bundschuh & Alvarado 2012, pp. 160, 162–165.

- ↑ Lewis & Valez 2015, p. 141.

- ↑ Lewis & Valez 2015, p. 143.

- ↑ Lewis & Valez 2015, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ Andreani & Gloaguen 2016, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ UNEP-WCMC 2022a, map.

- ↑ UNEP-WCMC 2022b, map.

- ↑ Briggs et al. 2013, pp. 318–319.

- ↑ UNEP-WCMC 2022a, sec. 'Belize Protected Areas'.

- ↑ UNEP-WCMC 2022b, sec. 'Guatemala Protected Areas'.

- ↑ Briggs et al. 2013, pp. 320–321.

- ↑ Briggs et al. 2013, pp. 320–321, 323, 326.

- ↑ Briggs et al. 2013, p. 323.

- ↑ Briggs et al. 2013, pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Briggs et al. 2013, p. 322.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 French & Schenk 2004.

- ↑ French & Schenk 2006.

- ↑ Andreani & Gloaguen 2016, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Andreani & Gloaguen 2016, pp. 73–74, figs. 2-3.

- 1 2 3 Andreani & Gloaguen 2016, p. 77.

- ↑ Bundschuh & Alvarado 2012, p. 80.

- ↑ Martens 2009, p. 18.

- 1 2 Steel & Davidson 2020a, foldout map.

- ↑ Andreani & Gloaguen 2016, p. 94.

- 1 2 Martens 2009, p. 23.

- ↑ Andreani & Gloaguen 2016, pp. 92–94.

- ↑ Martens 2009, pp. 120–122.

- ↑ Martens 2009, p. 122.

- ↑ Martens 2009, pp. 122, 124.

- ↑ Martens 2009, pp. 126, 135.

- ↑ Martens 2009, p. 121, fig. 4.1.

- ↑ Martens 2009, p. 123, fig. 4.2.

- ↑ Evenick 2021, p. 6, fig. 4.

- 1 2 Carter et al. 2019, p. 89.

- ↑ Hogan 2007, ???.

- ↑ Awe et al. 1990, p. ???.

- ↑ Bolland & Shoman 1977, pp. 34–37.

- 1 2 3 4 Balboni & Palacio 2007, p. 124.

- ↑ Bolland & Shoman 1977, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Wallace 2011, p. 25.

- ↑ Hammond 1983, p. 22.

- ↑ Nichols & Pool 2012, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Pendergast 1993, p. 4.

- ↑ Nichols & Pool 2012, p. 71.

- ↑ Pendergast 1993, p. 7.

- ↑ Beardall 2021, p. 28.

- ↑ Oliphant 1925, p. 40.

- ↑ Pamberton 2012, pp. 187–189.

- ↑ Francis 1924, pp. 532–557, pt. XV cap. 88.

- ↑ Neiemer 2019, p. 33.

- ↑ Smith 2021, pp. 584–585.

- ↑ IUCN 1992, p. 124.

- ↑ IUCN 1992, pp. 143, 150.

- ↑ Burdon 1931, p. 165.

- ↑ Calderon Quijano 1944, p. 322.

- ↑ Finamore 1994, pp. 103, 105.

- ↑ Conover Blancas 2016, pp. 111–115.

- 1 2 Martens 2009, p. 124.

- 1 2 Dixey 1957, sec. 'British Honduras' paras. 1-2.

- ↑ Sapper 1899, pp. 24–25.

Full citations

- Balboni, Barbara S.; Palacio, Joseph O., eds. (2007). Taking stock : Belize at 25 years of independence. Belize collection. Benque Viejo: Cubola Productions. ISBN 9789768161185. OCLC 182632403.

- Bateson, J. H.; Hall, I. H. S. (1977). The geology of the Maya Mountains, Belize. Overseas Memoir no. 3. London: Institute of Geological Sciences; Natural Environment Research Council. ISBN 9780118807654. OCLC 3530491.

- Bolland, Orlando Nigel; Shoman, Assad (1977). Land in Belize, 1765-1871. Law and society in the Caribbean ; no. 6. Mona, Jamaica: Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of the West Indies. hdl:2027/txu.059173018664366. OCLC 3369638.

- Bundschuh, J.; Alvarado, G. E., eds. (2012) [First published 2007]. Central America: Geology, Resources and Hazards (Reprint of 1st ed.). London: Taylor & Francis. doi:10.1201/9780203947043. ISBN 9780429074370. OCLC 905983675.

- Burdon, J. A., ed. (1931). From the earliest date to A. D. 1800. Archives of British Honduras ... Being extracts and précis from records, with maps. Vol. 1. London: Sifton, Praed & Co. hdl:2027/mdp.39015028737008. OCLC 3046003.

- Calderon Quijano, J. A. (1944). Belice, 1663(?)-1821 : historia de los establecimientos británicos del Río Valis hasta la independencia de Hispano-américa. Publicaciones de la Escuela de Estudios Hispanoamericanos de la Universidad de Sevilla ; 5 (no. general) ; Serie 2a ; Monografías ; no. 1. Seville: Escuela de Estudios Hispanoamericanos. hdl:2027/txu.059173022907891. OCLC 2481064.

- Dengo, G.; Case, J. H., eds. (1990). The Caribbean Region. The Geology of North America ; v. H. Boulder, Colo.: Geological Society of America. hdl:2027/mdp.39015018862931. ISBN 9780813752129. OCLC 21909394.

- Dixon, Cyril George (1956). Geology of southern British Honduras. Belize: Government of British Honduras. hdl:2027/txu.059173023862052. OCLC 975471.

- Fowler, Henry (1879). A narrative of a journey across the unexplored portion of British Honduras, with a short sketch of the history and resources of the colony. Belize: Government Press. OCLC 19351121.

- Francis, C. B., ed. (1924). Ordinances, Chapters 1–152. The New Edition of the Consolidated Laws of British Honduras 1924 containing the Ordinances of the colony in force on the 21st day of July, 1924. Vol. 1. London: Waterlow & Sons. hdl:2027/mdp.35112101939298. OCLC 4143433.

- Hermans, E., ed. (2020). A Companion to the Global Early Middle Ages. Leeds: Arc Humanities Press. doi:10.1515/9781942401766. ISBN 9781942401766. OCLC 1159724793. S2CID 241916138.

- Hoffmann, O. (2014). British Honduras: The invention of a colonial territory. Mapping and spatial knowledge in the 19th century. Benque Viejo, Belize, and Bondy, France: Cubola and Institut de recherche pour le développement. OCLC 914182564.

- Hooper, E. D. M. (1887). Report upon the forests of Honduras. Kurnool, India: Kurnool Collectorate Press. OCLC 39000844.

- Hummel, C. (1921). Report on the forests of British Honduras: with suggestions for a far reaching forest policy. London: Colonial Research Committee. OCLC 499880434.

- IUCN (1992). Nearctic and Neotropical. Protected Areas of the World: A review of national systems. Vol. 4. Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK: IUCN. ISBN 2831700930. OCLC 27471629.

- Valdez, Fred (2015). Lewis, Brandon S.; Valdez, Fred (eds.). Research reports from the Programme for Belize Archaeological Project. Occasional papers / Mesoamerican Archaeological Research Laboratory. Vol. 9. Austin TX: Center for Archaeological and Tropical Studies; University of Texas at Austin. doi:10.15781/T2TM72H3C. hdl:2152/62448. OCLC 793922390.

- Mann, P., ed. (1999). Caribbean Basins. Sedimentary Basins of the World. Vol. 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 0444826491. OCLC 43540498.

- Nairn, A. E. M.; Stehli, F. G., eds. (1975). The Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. The Ocean Basins and Margins. Vol. 3. New York and London: Plenum Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-8535-6. ISBN 978-1-4684-8537-0. OCLC 1255226320.

- Nichols, Deborah L.; Pool, Christopher A., eds. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Mesoamerican Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195390933.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-539093-3. OCLC 761538187.

- Ower, Leslie Hamilton (1928a). The geology of British Honduras. Belize: Printed by the Clarion. OCLC 5868136.

- Sapper, K. (1896a). Sobre la geografía física y la geología de la península de Yucatán. Instituto geológico de México ; boletín núm. 3. México: Oficina Tip. de la Secretaría de Fomento. hdl:2027/hvd.tz1rcx. OCLC 4688830.

- Sapper, K. (1898). Notes on the topographical, geological and botanical maps of British Honduras. Belize: Angelus Press. OCLC 39682724.

- Sapper, K. (1899). Über gebirgsbau und boden des nördlichen Mittelamerika. Petermanns Mitteilungen no. 127. Gotha: Justus Perthes. OCLC 2380594.

- USDI (1947). Place names in British Honduras. Recommended list ; no. 138. Washington DC: Department of the Interior, Division of Geography. hdl:2027/hvd.hxnxli.

- Westphal, H.; Eberli, G. P.; Riegl, B., eds. (2010). Carbonate Depositional Systems: Assessing Dimensions and Controlling Parameters: The Bahamas, Belize and the Persian/Arabian Gulf. London: Taylor & Francis. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9364-6. ISBN 978-90-481-9363-9. LCCN 2010932327. OCLC 668098092. S2CID 131785753.

Journals

- Abramiuk, M. A.; Dunham, P. S.; Cummings, L. S.; Yost, C.; Pesek, T. J. (2011). "Linking Past and Present: A Preliminary Paleoethnobotanical Study of Maya Nutritional and Medicinal Plant Use and Sustainable Cultivation in the Southern Maya Mountains, Belize". Ethnobotany Research and Applications. 9: 257–273. doi:10.17348/era.9.0.257-273. hdl:10125/21029.

- Andreani, L.; Gloaguen, R. (2016). "Geomorphic analysis of transient landscapes in the Sierra Madre de Chiapas and Maya Mountains (northern Central America); implications for the North American-Caribbean-Cocos plate boundary". Earth Surface Dynamics. 4 (1): 71–102. Bibcode:2016ESuD....4...71A. doi:10.5194/esurf-4-71-2016.

- Awe, J.; Bill, C.; Campbell, M.; Cheetham, D. (1990). "Early Middle Formative Occupation in the Central Maya Lowlands: Recent Evidence from Cahal Pech, Belize". Papers from the Institute of Archaeology. 1: 1–5. doi:10.5334/pia.358.

- Bellamy, J. (1889). "Expedition to the Cockscomb Mountains, British Honduras". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society. New Series. 11 (9): 542–552. doi:10.2307/1801336. hdl:2027/uc1.32106015214742. JSTOR 1801336.

- Briggs, V. S.; Mazzotti, F. J.; Harvey, R. G.; Barnes, T. K.; Manzanero, R.; Meerman, J. C.; Walker, P.; Walker, Z. (2013). "Conceptual Ecological Model of the Chiquibul/Maya Mountain Massif, Belize". Human and Ecological Risk Assessment. 19 (2): 317–340. doi:10.1080/10807039.2012.685809. S2CID 85575714.

- Burg, Marieka B.; Tibbits, Tawny L. B.; Harrison-Buck, Eleanor (2021). "Advances in Geochemical Sourcing of Granite Ground Stone: Ancient Maya Artifacts from the Middle Belize Valley". Advances in Archaeological Practice. 9 (4): 338–358. doi:10.1017/aap.2021.26. S2CID 244491766.

- Calderon Quijano, J. A. (1975). "Cartografía de Belice y Yucatán". Anuario de Estudios Americanos. 32: 599–637. hdl:10261/34733. ISSN 0210-5810. ProQuest 1300365669.

- Carter, N.; Santini, L.; Barnes, A.; Opitz, R.; White, D.; Safi, K.; Davenport, B.; Brown, C.; Witschey, W. (2019). "Country Roads: Travel, Visibility, and Late Classic Settlement in the Southern Maya Mountains". Journal of Field Archaeology. 44 (2): 84–108. doi:10.1080/00934690.2019.1571373. S2CID 134366469.

- Casas-Peña, Juan Moisés; Ramírez-Fernández, Juan Alonso; Velasco-Tapia, Fernando; Alemán-Gallardo, Eduardo Alejandro; Augustsson, Carita; Weber, Bodo; Frei, Dirk; Jenchen, Uwe (2021). "Provenance and tectonic setting of the Paleozoic Tamatán Group, NE Mexico: Implications for the closure of the Rheic Ocean". Gondwana Research. 91: 205–230. Bibcode:2021GondR..91..205C. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2020.12.012. hdl:10566/6154. S2CID 233830928.

- Conover Blancas, C. (2016). "De los frentes de batalla a los linderos tangibles en el Sureste Novohispano. La demarcación de los límites de los territorios ampliados de los establecimientos británicos del Walix por la convención de Londres de 1786". Revista de Historia de América (152): 91–134. doi:10.35424/rha.152.2016.357. JSTOR 48581762. S2CID 257474514.

- Davidson, I.; Pindell, J.; Hull, J. (2020). "The basins, orogens and evolution of the southern Gulf of Mexico and Northern Caribbean". Special Publications of the Geological Society of London. 504 (sn): 1–27. doi:10.1144/SP504-2020-218. S2CID 231884613.

- Dixey, F. (1957). "Colonial Geological Surveys 1947–1956: a review of progress during the past ten years". Colonial Geology and Mineral Resources. Bulletin Supplement no. 2. ISSN 0366-5968. OCLC 7621820.

- Evenick, J. C. (2021). "Glimpses into Earth's history using a revised global sedimentary basin map". Earth-Science Reviews. 215: 103564. Bibcode:2021ESRv..21503564E. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103564. S2CID 233950439.

- Goldscheider, N.; Chen, Z.; Auler, A. S.; Bakalowicz, M.; Broda, S.; Drew, D.; Hartmann, J. (2020). "Global distribution of carbonate rocks and karst water resources". Hydrogeology Journal. 28 (sn): 1661–1677. Bibcode:2020HydJ...28.1661G. doi:10.1007/s10040-020-02139-5. S2CID 216032707.

- Groff, K.; Axelrod, M. (2013). "A Baseline Analysis of Transboundary Poaching Incentives in Chiquibul National Park, Belize". Conservation and Society. 11 (3): 277–290. doi:10.4103/0972-4923.121031. JSTOR 26393116.

- Guzman-Hidalgo, E.; Grajales-Nishimura, J. M.; Eberli, G. P.; Aguayo-Camargo, J. E.; Urrutia-Fucugauchi, J.; Perez-Cruz, L. (2021). "Seismic stratigraphic evidence of a pre-impact basin in the Yucatan Platform; morphology of the Chicxulub Crater and K/Pg boundary deposits". Marine Geology. 441: 106594. Bibcode:2021MGeol.441j6594G. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2021.106594.

- Hammond, Norman (March 1983). "The development of Belizean archaeology". Antiquity. 57 (219): 19–27. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00054946. S2CID 163374681.

- Keppie, D. F.; Keppie, J. D. (2014). "The Yucatan, a Laurentian or Gondwanan fragment? Geophysical and palinspastic constraints". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 103 (5): 1501–1512. Bibcode:2014IJEaS.103.1501K. doi:10.1007/s00531-013-0953-x. S2CID 140195140.

- King, David T.; Zou, Haibo; Gill, Karena K.; Petruny, Lucille W.; Smith, Fay (2019). "Detrital Zircons from the Margaret Creek Formation, Corozal Basin, Northern Belize". GeoGulf Transactions. 69: 221–231. OCLC 1347487208.

- Maldonado, Roberto; Ortega-Gutiérrez, Fernando; Ortíz-Joya, Guillermo A. (2018). "Subduction of Proterozoic to Late Triassic continental basement in the Guatemala suture zone: A petrological and geochronological study of high-pressure metagranitoids from the Chuacús complex". Lithos. 308–309: 83–103. Bibcode:2018Litho.308...83M. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2018.02.030.

- Martens, Uwe; Weber, Bodo; Valencia, Victor A. (2010). "U/Pb geochronology of Devonian and older Paleozoic beds in the southeastern Maya block, Central America: Its affinity with peri-Gondwanan terranes". GSA Bulletin. 122 (5–6): 815–829. Bibcode:2010GSAB..122..815M. doi:10.1130/B26405.1.

- Mikolas, M.; Vilamova, S.; Kiraly, A.; Pechar, R.; Tvrdy, J.; Wajdova, L.; Mikolas, M. (2017). "Newly verified occurrences of industrial minerals in Belize". Acta Montanistica Slovaca. 22 (1): 215–224. ISSN 1335-1788.

- Oliphant, J. N. (1925). "Development of Forestry in British Honduras". Empire Forestry Journal. 4 (1): 39–44. JSTOR 42591408.

- Ortega-Gutierrez, F.; Solari, L. A.; Ortega-Obregon, C.; Elias-Herrera, M.; Martens, U.; Moran-Ical, S.; Chiquin, M. (2007). "The Maya-Chortis boundary; a tectonostratigraphic approach". International Geology Review. 49 (11): 996–1024. Bibcode:2007IGRv...49..996O. doi:10.2747/0020-6814.49.11.996. S2CID 140702379.

- Ower, Leslie Hamilton (1928b). "Geology of British Honduras". Journal of Geology. 36 (6): 494–509. Bibcode:1928JG.....36..494O. doi:10.1086/623544. JSTOR 30059946. S2CID 128468335.

- Pemberton, Rita (2012). "The environmental impact of colonial activity in Belize". Historia ambiental latinoamericana y caribeña, 2012, Vol.I (2), p.180-192. 1 (2): 180–192. ISSN 2237-2717.

- Pendergast, David M. (March 1993). "The Center and the Edge: Archaeology in Belize, 1809–1992". Journal of World Prehistory. 7 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1007/BF00978219. JSTOR 25800626. S2CID 161362847.

- Penn, M. G.; Sutton, D. A.; Monro, A. (2004). "Vegetation of the Greater Maya Mountains, Belize". Systematics and Biodiversity. 2 (1): 21–44. doi:10.1017/S1477200004001318. S2CID 86253268.

- Ross, C. H.; Stockli, D. F.; Rasmussen, C.; Gulick, S. P. S.; Graaff, S. J.; Claeys, P.; Zhao, J. (2021). "Evidence of Carboniferous arc magmatism preserved in the Chicxulub impact structure". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 134 (1–2): 241–260. doi:10.1130/B35831.1. hdl:10044/1/99016. S2CID 238043996.

- Sapper, Karl Theodor (1896b). "Geology of Chiapas, Tabasco and the Peninsula of Yucatan". Journal of Geology. 4 (8): 938–947. Bibcode:1896JG......4..938S. doi:10.1086/607658. JSTOR 30054992. S2CID 128758642.

- Smith, Cathy (2021). "From colonial forestry to 'community-based fire management': the political ecology of fire in Belize's coastal savannas, 1920 to present". Journal of Political Ecology. 28 (1): 577–602. doi:10.2458/jpe.2989. S2CID 238661314.

- Villeneuve, M.; Marcaillou, B. (2013). "Pre-Mesozoic origin and paleogeography of blocks in the Caribbean, South Appalachian and West African domains and their impact on the post "Variscan" evolution". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 184 (1–2): 5–20. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.184.1-2.5.

- Vitelli, Karen D. (Summer 1983). "The Antiquities Market". Journal of Field Archaeology. 10 (2): 213–228. doi:10.1179/009346983792208523. JSTOR 529611.

- Wallace, Colin (May 2011). "Reconnecting Thomas Gann with British Interest in the Archaeology of Mesoamerica: An Aspect of the Development of Archaeology as a University Subject". Bulletin of the History of Archaeology. 21 (1): 23. doi:10.5334/bha.2113.

- Zhao, J.; Xiao, L.; Gulick, S. P. S.; Morgan, J. V.; Kring, D.; Urrutia-Fucugauchi, J. (2020). "Geochemistry, geochronology and petrogenesis of Maya Block granitoids and dykes from the Chicxulub Impact Crater, Gulf of México: Implications for the assembly of Pangea". Gondwana Research. 82 (sn): 128–150. Bibcode:2020GondR..82..128Z. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2019.12.003. S2CID 214359672.

Theses

- Beardall, Antonio (2021). Public Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Management in Belize: Successes and Shortcomings (MA). Northern Arizona University. ISBN 9798738649813. ProQuest 2541908363.

- Bushong, A. D. (1961). Agricultural settlement in British Honduras : a geographic interpretation of its development (PhD). University of Florida. OCLC 1005996786. ProQuest 302046774.

- Finamore, D. R. (1994). Sailors and slaves on the wood-cutting frontier: Archaeology of the British Bay Settlement, Belize (PhD). Boston University. OCLC 35313422. ProQuest 304114781.

- Groff, K. (1961). A baseline analysis of poaching in Chiquibul National Park (MS). Michigan State University. OCLC 931849322. ProQuest 889144093.

- Martens, U. (2009). Geologic evolution of the Maya Block (southern edge of the North American plate): An example of terrane transferral and crustal recycling (PhD). Stanford University. OCLC 465332905. ProQuest 304999167.

- Neiemer, Daniela (2019). From Global Policy to Local Reality at a World Heritage Site : A Critical Analysis of the Outreach and Educational Program of the 'Friends of Nature' organization in southern Belize (Diploma). Universitat Hamburg. ISBN 9783961163021. OCLC 1189586751.

- Thompson, A. E. (2019). Comparative Processes of Sociopolitical Development in The Foothills of The Southern Maya Mountains (PhD). University of New Mexico. OCLC 1156632404. ProQuest 2384857821.

- Stott, G. L. (2019). Endemism hotspots in the flora of Belize (PhD). Oxford University. OCLC 1289272432.

Maps

- IGS (1975). Geological map of the Maya Mountains, Belize (Map). 1:130,000. Directorate of Overseas Surveys no. 1205. London: Natural Environment Research Council. OCLC 32235698.

- Faden, W. (1787). A map of a part of Yucatan, or of that part of the eastern shore within the Bay of Honduras alloted [sic] to Great Britain for the cutting of logwood, in consequence of the Convention signed with Spain on the 14th July 1786 (Map). 1:400,000. London: Printed for William Faden. hdl:loc.gmd/g4820.ct008427. LCCN gm70000406.

- French, C. D.; Schenk, C. J. (2004). Map showing geology, oil and gas fields, and geologic provinces of the Caribbean Region (Map). 1:2,500,000. Open-File Report 97-470-K. Reston, Virg.: U.S. Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/ofr97470K.

- French, C. D.; Schenk, C. J. (2006). Map showing geology, oil and gas fields, and geologic provinces of the Gulf of Mexico region (Map). 1:2,500,000. Open-File Report 97-470-L. Reston, Virg.: U.S. Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/ofr97470L.

- Steel, I.; Davidson, I. (2020a). The basins and orogens of the Southern Gulf of Mexico map (Map). 1:4,000,000. Special Publications; v. 504; pp. 557-558. London: Geological Society of London. doi:10.1144/SP504-2020-2.

- Steel, I.; Davidson, I. (2020b). Map of the geology of the Northern Caribbean and the Greater Antillean Arc (Map). 1:4,000,000. Special Publications; v. 504; pp. 559-560. London: Geological Society of London. doi:10.1144/SP504-2020-3.

- Usher, A. (1888). Map of British Honduras (Map) (Revised ed.). 1:380,160. London: F. S. Weller.

Other

- EB (2012). "Cockscomb Range". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online ID place/Cockscomb-Range.

- EB (2017). "Maya Mountains". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online ID place/Maya-Mountains.

- Hogan, C. M. (2007). "Lubaantun - Ancient Village or Settlement in Belize" (Article). The Megalithic Portal. Surrey, Eng.: Andy Burnham. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- UNEP-WCMC (2022a). "Protected Area Profile for Belize from the World Database on Protected Areas, June 2022" (Database). Cambridge: Nature Conserved Programme. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- UNEP-WCMC (2022b). "Protected Area Profile for Guatemala from the World Database on Protected Areas, October 2022" (Database). Cambridge: Nature Conserved Programme. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

External links

![]() Media related to Maya Mountains at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Maya Mountains at Wikimedia Commons