The Wasatch Formation (Tw)[1] is an extensive highly fossiliferous geologic formation stretching across several basins in Idaho, Montana Wyoming, Utah and western Colorado.[2] It preserves fossils dating back to the Early Eocene period. The formation defines the Wasatchian or Lostcabinian (55.8 to 50.3 Ma), a period of time used within the NALMA classification, but the formation ranges in age from the Clarkforkian (56.8 to 55.8 Ma) to Bridgerian (50.3 to 46.2 Ma).

Wasatch fauna consists of many groups of mammals, including numerous genera of primates, artiodactyls, perissodactyls, rodents, carnivora, insectivora, hyaenodonta and others. A number of birds, several reptiles and fish and invertebrates complete the diverse faunal assemblages. Fossil flora and ichnofossils also have been recovered from the formation.

The formation, first named as Wasatch Group in 1873 by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, was deposited in alluvial, fluvial and lacustrine environments and comprises sandstones, siltstones, mudstones and shales with coal or lignite beds representing wet floodplain settings.

The Wasatch Formation is an unconventional tight gas reservoir formation in the Uinta and Piceance Basins of Utah and the coal seams of the formation are mined in Wyoming. At the Fossil Butte National Monument, the formation crops out underlying the Green River Formation. In the Silt Quadrangle of Garfield County, Colorado, the formation overlies the Williams Fork Formation.[3]

Description

Definition

The Wasatch Formation was first named as the Wasatch Group by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden in the 1873 edition of his original 1869 publication titled "Preliminary field report of the United States Geological Survey of Colorado and New Mexico: U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories", based on sections in the Echo and Weber Canyons, of the Wasatch Mountains.[4] In the language of the native Ute people, Wasatch means "mountain pass" or "low pass over high range."[5][6] According to William Bright, the mountains were named for a Shoshoni leader who was named with the Shoshoni term wasattsi, meaning "blue heron".[7]

Outcrops

At the base of Fossil Butte are the bright red, purple, yellow and gray beds of the Wasatch Formation. Eroded portions of these horizontal beds slope gradually upward from the valley floor and steepen abruptly. Overlying them and extending to the top of the butte are the much steeper buff-to-white beds of the Green River Formation, which are about 300 feet (91 m) thick. The Wasatch Formation ranges from about 3,000 feet (910 m) in the western part of the Uinta Basin, thinning to 2,000 feet (610 m) in the east.[8] In the Silt Quadrangle of Garfield County, Colorado, the formation overlies the Williams Fork Formation.[3] The formation is exposed in the Desolation and Gray Canyons pertaining to the Colorado Plateau in northeastern Utah,[9] and in Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area at the border of southwestern Wyoming and northeastern Utah.[10]

Extent

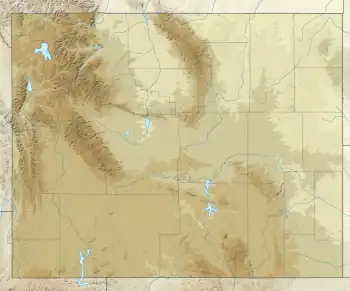

The Wasatch Formation is found across six states in the northwestern United States, from Montana[11] and Idaho in the north across Utah[12] and Wyoming to Colorado in the southwest. The formation is part of several geologic provinces; the eponymous Wasatch uplift, Uinta uplift, Green River, Piceance, Powder River, Uinta and Paradox Basins and the Colorado Plateau sedimentary province and Yellowstone province.[13]

In Montana, the formation overlies the Fort Union Formation and is overlain by the White River Formation.[14] There is a regional, angular unconformity between the Fort Union and Wasatch Formations in the northern portion of the Powder River Basin.[15]

Subdivision

Many local subdivisions of the formation exist, the following members have been named in the literature:[13]

| Member | States | Lithologies | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkali Creek Tongue | Wyoming | Mudstones and sandstones | [16] |

| Atwell Gulch | Colorado | Sandstones and mudstones | [17] |

| Bullpen | Wyoming | ||

| Cathedral Bluffs Tongue | Colorado, Wyoming | Mudstones and sandstones | [16] |

| Chappo | Wyoming | ||

| Cowley Canyon | Utah | ||

| Desertion Point Tongue | Wyoming | ||

| Hiawatha | Colorado, Utah, Wyoming | ||

| Kingsbury Conglomerate | Wyoming | Feldspathic conglomerates | [18][19] |

| Knight | Utah, Wyoming | ||

| La Barge | Wyoming | ||

| Lookout Mountain Conglomerate | Wyoming | Conglomerates | |

| Luman Tongue | Wyoming | [20] | |

| Main Body | Wyoming | Mudstones | [16][21] |

| Molina | Colorado | Sandstones | [17] |

| Moncrief | Wyoming | Feldspathic conglomerates | [18] |

| New Fork Tongue | Wyoming | ||

| Nightingale | Wyoming | ||

| Niland Tongue | Colorado, Wyoming | ||

| Ramsey Ranch | Wyoming | ||

| Red Desert Tongue | Wyoming | ||

| Renegade Tongue | Colorado, Utah | ||

| Shire | Colorado | Sandstones and mudstones | [17] |

| Tunp | Wyoming | ||

Lithologies and facies

In the Fossil Basin at the Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming, the Wasatch Formation consists primarily of brightly variegated mudstones with subordinate interbedded siltstones, sandstones, and conglomerates and represents deposition on an intermontane alluvial plain.[22] In Mesa County, Colorado, the formation comprises interbedded purple, lavender, red, and gray claystones and shales with local lenses of gray and brown sandstones, conglomeratic sandstones, and volcanic sandstones that are predominantly fluvial and lacustrine in origin.[23] Along the western margin of the Powder River Basin, the Wasatch Formation contains two thick conglomeratic members (in descending order, the Moncrief Member and Kingsbury Conglomerate Member).[24]

The Molina Member of the formation is a zone of distinctly sandier fluvial strata. The over- and underlying members of the Molina are the Atwell Gulch and Shire members, respectively. These members consist of infrequent lenses of fluvial-channel sandstones interbedded within thick units of variegated red, orange, purple and gray overbank and paleosol mudstones.[17]

The Molina Member represents a sudden change in the tectonic and/or climatic regimes, that caused an influx of laterally-continuous, fine, coarse and locally conglomeratic sands into the basin. The type section of the Molina is located near the small town of Molina on the western edge of the basin and is about 90 metres (300 ft) thick. These sandy strata of the Molina Member form continuous, erosion-resistant benches that extend to the north of the type section for approximately 25 kilometres (16 mi). The benches are cut by canyons or "gulches", from which the Atwell Gulch and Shire Gulch members get their names. The Molina forms the principle target within the Wasatch Formation for natural gas exploration, although it is usually called the "G sandstone" in the subsurface.[17]

Provenance

Detrital zircons collected from the middle part of the formation in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming, where the Wasatch Formation reaches a thickness of more than 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) were gathered for U-Pb geochronological analysis. The detrital zircon age spectrum ranged from 1433-2957 Ma in age, and consisted of more than 95% Archean age grains, with an age peak of about 2900 Ma. The 2900 Ma age peak is consistent with the age of Archean rocks at the core of the Bighorn Mountains. The sparse Proterozoic grains were likely derived from the recycling of Paleozoic sandstone units. The analysis concluded that the Wasatch sandstone is a first cycle sediment, the Archean core of the Bighorn uplift was exposed and shedding sediment into the Powder River Basin during time of deposition of the Wasatch Formation and the Powder River Basin Wasatch detrital zircon age spectra are distinct from the coeval Willwood Formation in the Bighorn Basin west of the Bighorn Mountains.[25] Cobbles and pebbles in the Wasatch are rich in feldspathic rock fragments, with individual samples containing as much as 40 percent,[26] derived from erosion of the Precambrian core of the Bighorn Mountains.[24] Part of the feldspar has been replaced by calcite cement.[27] Glauconite is present in the Wasatch, although always in volumes of less than 1 percent of the grains. It most probably was derived from the nearby, friable, glauconite-bearing Mesozoic strata of the eastern Bighorn Mountains.[18]

The presence of the Kingsbury Conglomerate at the base of the Wasatch Formation indicates that tectonic activity in the immediate vicinity of the Powder River Basin was intensifying. The conglomerate consists of Mesozoic and Paleozoic rock fragments. The lack of Precambrian fragments indicates that the metamorphic core of the Bighorn Mountains had not been dissected by this early deformation.[19] Deformation in the upper part of the formation has been interpreted as the result of the last phase of uplift during the Laramide orogeny.[28]

Correlations

The basal part of the Wasatch Formation is equivalent to the Flagstaff Formation in the southwest part of the Uinta Basin.[29] The Wasatch Formation is correlated with the Sentinel Butte and Golden Valley Formations of the Williston Basin.[30][31]

Paleontological significance

The Wasatch Formation is the defining formation for the Wasatchian, ranging from 55.8 to 50.3 Ma, within the NALMA classification. The Wasatchian followed the Clarkforkian stage (56.8-55.8 Ma) and is defined by the simultaneous first appearance of adapid and omomyid euprimates, hyaenodontid creodonts, perissodactyls and artiodactyls.[32] The deposits of the formation were laid down during a period of globally high temperatures during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). Mean annual temperatures were around 25 °C (77 °F) and temperature variations were minimal during this time.[33]

At the Fossil Butte National Monument, the Wasatch Formation preserved ichnofossils attributed to arthropods and described as Lunulichnus tuberosus.[34] Trace fossils are common within the upper part of the Main Body Member. These traces occur in three distinct alluvial depositional settings: flood basin/alluvial plain, crevasse splay, and fluvial channel. Flood basin deposits (dominated by alluvial paleosols with pronounced color variegation) are characterized by common Planolites, rare Skolithos and small, meniscate plug-shaped burrows, possibly Celliforma.[35]

Crevasse splay deposits (current-rippled to planar laminated, fine-grained sandstone to siltstone) are characterized by a mixed assemblage of vertical (Arenicolites, Skolithos, unwalled sinuous shafts, shafts with discoidal lenses of sediment), sub-vertical (Camborygma and Thalassinoides) and horizontal (Scoyenia, Rusophycus, Taenidium, Planolites and Palaeophycus) burrows. Large, vertically oriented burrows (Camborygma, cf. Ophiomorpha, Spongeliomorpha and Thalassinoides) are the dominant forms within fluvial channel deposits.[35]

Fossil content

Among the following fossils have been found in the formation:[2]

Mammals

- Primates

- Absarokius abbotti[36][37]

- A. gazini[38]

- Anaptomorphus aemulus[39]

- Anemorhysis sublettensis[40]

- Arapahovius gazini

- Artimonius nocerai[41]

- A. witteri[41]

- Cantius frugivorus[42][36][43][44]

- C. mckennai[42]

- C. nunienus[45]

- Carpodaptes cf. hazelae[46]

- Chiromyoides minor[46]

- Chlororhysis knightensis[40]

- Copelemur australotutus[47][44]

- C. praetutus[42]

- C. tutus[48]

- Ignacius frugivorus[46]

- Loveina minuta[37]

- L. sheai[49]

- L. zephyri[50]

- Microsyops angustidens[42]

- M. knightensis[45][51]

- M. latidens[38][51]

- M. cf. elegans[52]

- M. cf. scottianus[45]

- Notharctus robinsoni[45]

- N. venticolus[45]

- Omomys carteri[45][39]

- O. lloydi[45]

- Plesiadapis dubius[42][53]

- Plesiadapis cf. cookei[54]

- Plesiadapis cf. rex[46]

- Simpsonlemur cf. jepseni[42]

- Smilodectes sororis[55]

- Steinius cf. vespertinus[42]

- Tetonius matthewi[56]

- Tetonoides pearcei[42][57]

- cf. Trogolemur myodes[37]

- Uintanius rutherfurdi[45]

- Utahia carina[41]

- Walshina mcgrewi[39]

- Washakius insignis[45]

- W. izetti[45]

- cf. Choctawius sp.[57]

- Cantius sp.[36]

- Carpolestes sp.[42]

- Chlororhysis sp.[37]

- Loveina sp.

- Microsyops sp.[57]

- Notharctus sp.[58][59]

- Omomys sp.[60]

- Phenacolemur sp.[57][44]

- Picrodus sp.[61]

- Tetonius sp.

- Trogolemur sp.[41]

- Uintasorex sp.

- Phenacolemurinae indet.[42]

- Artiodactyls

- Antiacodon pygmaeus[39]

- Bunophorus cf. etsagicus[40]

- B. grangeri[62]

- B. macropternus[36]

- B. sinclairi[63]

- Diacodexis secans[42][64][62]

- Gagadon minimonstrum[65]

- Hexacodus pelodes[60][36]

- H. uintensis[40][66]

- Antiacodon sp.[45]

- Bunophorus sp.[45]

- Diacodexis sp.[42][36]

- Hexacodus sp.[45]

- Microsus sp.[45]

- Dichobunidae indet.[60]

- Perissodactyls

- Arenahippus pernix[57][67]

- Cardiolophus semihians[56]

- cf. Dilophodon destitutus[68]

- Eotitanops borealis[36][69]

- Heptodon calciculus[36][69][62]

- H. posticus[69]

- Homogalax protapirinus[57]

- Hyrachyus modestus[39][36]

- Hyracotherium vasacciense[69][60][70]

- Lambdotherium popoagicum[69][62]

- Minippus index[36][71]

- Orohippus proteros[36]

- Orohippus cf. pumilus[52]

- Palaeosyops fontinalis[45][52]

- Protorohippus venticolum[36][71][72]

- Xenicohippus craspedotum[73]

- Eotitanops borealis[45]

- Helaletes sp.[45]

- Heptodon sp.[40]

- Homogalax sp.[60]

- Hyrachyus sp.[45][52]

- Hyracotherium sp.[45][42][60]

- Lambdotherium sp.[49]

- Orohippus sp.[45]

- Palaeosyops sp.[58]

- Equidae indet.[42][73]

- Helaletidae indet.[52]

- Isectolophidae indet.[45]

- Perissodactyla indet.[42]

- Tapiroidea indet.[60]

- Hyaenodonta

- Gazinocyon vulpeculus[74]

- Iridodon datzae[75]

- Prolimnocyon antiquus[42][36][75]

- Prototomus secundarius[76]

- Tritemnodon cf. strenuus[42]

- Prolimnocyon sp.[45]

- Sinopa sp.[45]

- Thinocyon sp.[45]

- Tritemnodon sp.[45]

- Hyaenodontidae indet.[77]

- Acreodi

- Carnivora

- Cimolesta

- Amaramnis gregoryi[60]

- Esthonyx acutidens[69]

- Esthonyx cf. bisulcatus[83]

- Palaeoryctes cruoris

- Palaeoryctes cf. punctatus

- ?Trogosus cf. latidens[60]

- Esthonyx sp.[45][42][36]

- Trogosus sp.[45]

- Dinocerata

- Erinaceomorpha

- Adunator meizon

- Eutheria

- Aceroryctes dulcis[56]

- Arctocyon nexus[84]

- Bessoecetor cf. septentrionalis[85]

- Chriacus oconostotae

- Lambertocyon gingerichi

- Palaeosinopa incerta[86]

- P. lacus[87]

- Palaeosinopa cf. didelphoides[60]

- cf. Palaeosinopa lutreola[60]

- Thryptacodon australis

- T. pseudarctos[88]

- Chriacus sp.[89]

- Claenodon sp.

- Ferae

- Ambloctonus major[60]

- Brachianodon westorum[45]

- Didymictis altidens[69][45][60][40]

- D. cf. protenus[90]

- Oxyaena forcipata[76]

- O. lupina[77]

- Protictis agastor

- P. paralus

- Raphictis cf. gausion

- Tubulodon pearcei[42]

- Tytthaena parrisi

- Uintacyon asodes

- Viverravus cf. acutus[60]

- V. gracilis[45]

- V. lutosus[60][36]

- V. minutus[45][52]

- V. sicarius[45]

- Didymictis sp.[42]

- Patriofelis sp.[45]

- Viverravus sp.[90]

- Glires

- Acritoparamys francesi[91]

- Knightomys depressus[42][91]

- K. huerfanensis[92][91][76]

- Leptotomus parvus[52]

- Lophiparamys murinus[57]

- Microparamys hunterae[57]

- M. minutus[39]

- Mysops fraternus[39]

- ?Notoparamys blochi[79]

- Paramys copei[60][36]

- P. delicatior[39]

- P. delicatus[39]

- P. excavatus[60][69][92]

- P. taurus[57]

- P. wyomingensis[42]

- Pauromys schaubi[39]

- Pseudotomus robustus[92]

- Reithroparamys delicatissimus[39][92]

- R. huerfanensis[39][92]

- R. cf. debequensis[79]

- Sciuravus bridgeri[39]

- S. nitidus[42][52]

- S. wilsoni[60]

- Thisbemys perditus[91]

- Tuscahomys ctenodactylops[91][57][93]

- Microparamys sp.[45][39]

- Paramys sp.[94]

- Reithroparamys sp.[39][40]

- Tillomys sp.[39]

- Cylindrodontidae indet.[45]

- Paramyidae indet.[69][45][39]

- Rodentia indet.[77]

- Sciuravidae indet.[39]

- Insectivora

- Apatemys bellulus[42]

- A. bellus[39]

- A. cf. whitakeri[87]

- Labidolemur soricoides

- Unuchinia dysmathes

- Apatemys sp.[45][89][36]

- Leptictida

- Lipotyphla

- Macroscelidea

- Multituberculata

- Ectypodus cf. powelli

- Neoplagiaulax cf. hazeni

- Neoplagiaulax cf. hunteri

- Ptilodus kummae

- Mesodma sp.

- Ectypodus sp.[57]

- Parectypodus sp.[89]

- ?Prochetodon sp.[94]

- Ptilodus sp.

- Pantodonta

- Pholidota

- Palaeanodon sp.[83]

- Placentalia

- Copecion brachypternus[99]

- Ectocion collinus

- E. osbornianus[53][57]

- E. superstes[79]

- Hyopsodus loomisi[42]

- H. minor[48]

- H. minusculus[39][52]

- H. paulus[57]

- H. powellianus[42][48]

- H. wortmani[36]

- H. cf. mentalis[40]

- H. cf. walcottianus[64]

- Meniscotherium chamense[69][100]

- M. cf. robustum[79]

- M. cf. tapiacitum[42][70]

- Phenacodus grangeri

- P. intermedius[42]

- P. trilobatus[97]

- P. vortmani[42][69]

- Ectocion sp.

- Hyopsodus sp.[45][58][42]

- Phenacodus sp.[42][58]

- Soricomorpha

- Leptacodon cf. munusculum

- Nyctitherium serotinum[39]

- Leptacodon sp.[57]

- Wyonycteris sp.[57]

- Taeniodonta

- Theriiformes

- Copedelphys innominata[102]

- Herpetotherium knighti[42][92]

- H. innominatum[42]

- Peradectes elegans

- P. chesteri[42]

- Peratherium edwardi[40]

- P. marsupium[42]

- Ectoganus sp.[42][40][83]

- Oodectes sp.[45]

- Paleotomus sp.[42]

- Stylinodon sp.[103]

- Uintacyon sp.[45]

- Epoicotheriidae indet.[45]

- Leptictidae indet.[45]

- Marsupialia indet.[60]

- Metacheiromyidae indet.[45]

- Nyctitheriidae indet.[89]

- Oxyaenidae indet.[69]

- Pantolestidae indet.[45]

- Stylinodontidae indet.[45]

Birds

- Eocrex primus[104]

- Limnofregata hutchisoni[105]

- Presbyornis sp.[58]

Reptiles

- Anosteira ornata[45]

- Apodosauriscus minutus

- Arpadosaurus gazinorum[49]

- A. sepulchralis[106]

- Baena arenosa[80][107]

- Boavus occidentalis[45]

- Boverisuchus vorax[45]

- Calamagras primus[45]

- Dunnophis microechinus[45]

- Echmatemys stevensoniana[45][80]

- Echmatemys cf. cibollensis[80]

- Emys wyomingensis[80]

- Entomophontes incrustatus[106]

- Eodiploglossus borealis

- cf. Eoglyptosaurus donohoei[108]

- Glyptosaurus agmodon[106]

- G. sylvestris[45]

- Machaerosaurus torrejonensis[45]

- Notomorpha testudinea[57]

- Palaeoxantusia amara[106]

- Palepidophyma lilliputiana[106]

- Parasauromalus olseni[45][80]

- Provaranosaurus fatuus[106]

- Psilosemys wyomingensis

- Restes rugosus[45]

- Saniwa ensidens[45]

- Scincoideus grassator[106]

- Suzanniwana revenanta[106]

- Trionyx aequa[45]

- Xenochelys lostcabinensis[109]

- Xestops savagei[106]

- X. vagans[45]

- cf. Crocodylus affinis[80]

- Allognathosuchus sp.[80]

- Anolbanolis sp.

- Coniophis sp.[45]

- Echmatemys sp.[58]

- Tinosaurus sp.

- Palaeoxantusia sp.[45]

- Paranolis sp.

- Parasauromalus sp.

- Procaimanoidea sp.[45]

- Stylinodon sp.[69]

- Suzanniwana sp.

- Tinosaurus sp.[45]

- cf. Jepsibaena sp.

- cf. Restes sp.

- cf. Saniwa sp.

- Amphisbaenidae indet.[45]

- Anguidae indet.

- Anguimorpha indet.[57]

- Baenidae indet.[45]

- Crocodylia indet.[58]

- Crocodylidae indet.[80]

- Emydidae indet.[45]

- Gerrhonotinae indet.

- Glyptosaurinae indet.[45]

- Helodermatidae indet.

- Iguania indet.

- Lacertilia indet.[110][36]

- Squamata indet.[58]

- Trionychidae indet.[58]

Amphibians

Fish

Invertebrates

- Bivalves

- Gastropods

- Viviparus paludinaeformis[114]

- Ferrissia cf. minuta[114]

- Mollusks

Flora

- Allantodiopsis erosa[112][115]

- Allophylus flexifolia[116]

- Ampelopsis acerifolia[112]

- Beringiaphyllum cupanioides[117]

- Carya antiquorum[112]

- Castanea intermedia[112]

- Cercidiphyllum arcticum[112]

- Cissus marginata[112]

- Dillenites garfieldensis[112]

- Dombeya novimundi[116]

- Ficus artocarpoides[112]

- Ficus planicostata[112]

- Fraxinus eocenica[112]

- Hovenia cf. oregonensis[116]

- Metasequoia occidentalis[115]

- Nyssa alata[112]

- Osmunda greenlandica[112]

- Penosphyllum cordatum[112]

- Platanus raynoldsi[112]

- Platycarya americana[116]

- Populus wyomingiana[116]

- Prunus corrugis[112]

- Rhamnus goldiana[112]

- cf. Schoepfia republicensis[116]

- Stillingia casca[116]

- Syzygioides americana[116]

- Ternstroemites aureavallis[115]

- Zizyphus fibrillosus[112]

- Alnus sp.[116]

- Celtis sp.[110]

- Cinnamomophyllum sp.[116]

- Sloanea sp.[116]

- Apocynaceae indet.[116]

- Dicotyledonae indet.[116]

- Lauraceae indet.[116]

- cf. Magnoliales indet.[116]

Ichnofossils

- Lunulichnus tuberosus[34]

- Arenicolites[35]

- Camborygma[35]

- Celliforma[35]

- Palaeophycus[35]

- Planolites[35]

- Rusophycus[35]

- Scoyenia[35]

- Skolithos[35]

- Spongeliomorpha[35]

- Taenidium[35]

- Thalassinoides[35]

- cf. Ophiomorpha[35]

Herbivore expansion

The mammal fauna of the formation is part of the fourth phase of herbivore expansion spanning about 115 Ma from the Aptian to Holocene,[118] and correlated with the Wind River and Wilcox Formations of the United States and the Laguna del Hunco Formation of Argentina.[119]

Economic geology

Petroleum geology

The Wasatch Formation is a tight gas reservoir rock in the Greater Natural Buttes Field in the Uinta Basin of Utah and Colorado. The formation is characterized by porosity ranging from 6 to 20% and permeability of up to 1 mD. Based on 409 samples from the Wasatch Formation, average porosity is 8.75 percent and average permeability is 0.095 mD.[8] The production rates after 2 years are 100–1,000 mscf/day for gas, 0.35–3.4 barrel per day for oil, and less than 1 barrel per day for water. The water:gas ratio ranges from 0.1 to 10 barrels per million standard cubic feet, indicating that free water is produced along with water dissolved in gas in the reservoir.[120] Oil in the Bluebell-Altamont Field in the Uinta Basin and gas in the Piceance Creek Field in the Piceance Basin are produced from the Wasatch Formation.[121]

As of May 2019, tight gas from the Wasatch Formation and underlying Mesaverde Group has been produced more than 1.76 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of gas from over 3,000 wells in the Uinta Basin, mostly from the Natural Buttes gas field in the eastern part of the basin. In the Piceance Basin, the Mesaverde Group and Wasatch Formation produced more than 7.7 TCF from over 12,000 wells, mostly from the central part of the basin.[122]

Mining

Coal

Coal is mined from the Wasatch Formation in Wyoming. Together with the Fort Union Formation, the Wasatch Formation represents the thickest coal bed deposits in the state.[123]

Uranium

The fluvial sandstones contain uranium roll front deposits. The formation is the main producer of uranium in the state.[124] Ore zones contain uraninite and pyrite. Oxidized ores include uranophane, meta-autunite, and phosphuranylite.[125]

Wasatchian correlations

See also

References

- ↑ Shroba & Scott, 2001, p.3

- 1 2 Wasatch Formation at Fossilworks.org

- 1 2 Shroba & Scott, 2001, p.18

- ↑ Wasatch - USGS

- ↑ Wasatch County - Utah History Encyclopedia

- ↑ Van Cott, 1990, p.390

- ↑ Bright, 2004, p.549

- 1 2 Nelson & Hoffman, 2009, p.8

- ↑ Stratigraphy of the Desolation Canyon and Gray Canyon

- ↑ Stratigraphy of Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area

- ↑ Wasatch Formation - Montana - USGS

- ↑ Wasatch Formation - Utah - USGS

- 1 2 Wasatch "Group" - USGS

- ↑ Widmayer, 1977, p.18

- ↑ Widmayer, 1977, p.105

- 1 2 3 Roehler, 1991, B16

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lorenz et al., 1996, p.3

- 1 2 3 Whipkey et al., 1991, D15

- 1 2 Widmayer, 1977, p.11

- ↑ Luman Tongue Member at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Main Body Member at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Gunnells et al., 2016, p.984

- ↑ Carrara, 2000, p.8

- 1 2 Whipkey et al., 1991, D1

- ↑ Anderson et al., 2017

- ↑ Whipkey et al., 1991, D5

- ↑ Whipkey et al., 1991, D11

- ↑ Shroba & Scott, 2001, p.23

- ↑ Sanborn, 1981, p.259

- ↑ Widmayer, 1977, p.19

- ↑ Pocknall, 1987, p.30

- ↑ Anemone & Dirks, 2009, p.116

- ↑ Pocknall, 1987, p.172

- 1 2 Zonneveld et al., 2006, p.90

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Zonneveld et al., 2006, p.88

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Smith & Holroyd, 2003

- 1 2 3 4 Covert & Hamrick, 1993

- 1 2 Bown & Rose, 1987

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 West & Dawson, 1973

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gazin, 1962

- 1 2 3 4 Muldoon & Gunnell, 2002

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Alroy, 2002

- ↑ Honey, 1988

- 1 2 3 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.991

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 Gunnell & Bartels, 2002

- 1 2 3 4 Gunnell, 1994

- ↑ Beard, 1988

- 1 2 3 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.992

- 1 2 3 Holroyd & Strait, 2008

- ↑ Bown, 1979

- 1 2 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.990

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Clyde et al., 1997

- 1 2 3 4 Holroyd & Rankin, 2014

- ↑ Gazin, 1942

- ↑ Gunnell, 2002

- 1 2 3 4 Rankin & Holroyd, 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Strait et al., 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Foster, 2001

- ↑ Roehler, 1991

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Gazin, 1965

- ↑ Scott & Fox, 2005

- 1 2 3 4 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.1003

- ↑ Stucky & Krishtalka 1990

- 1 2 Krishtalka & Stucky, 1985

- ↑ Stucky & Covert, 2014

- ↑ Gunnell et al., 2016, p.1004

- ↑ Gingerich, 1991

- ↑ Zonneveld & Gunnell, 2003

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 West, 1973

- 1 2 3 Dorr, 1978

- 1 2 Froehlich, 2002

- 1 2 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.1000

- 1 2 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.1001

- ↑ Polly, 1996

- 1 2 Morlo & Gunnell, 2003

- 1 2 3 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.998

- 1 2 3 Gunnell, 1998

- ↑ Gingerich, 1982

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.995

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Zonneveld et al., 2000

- ↑ Guthrie, 1971

- ↑ Roehler, 1987

- 1 2 3 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.989

- ↑ Gazin, 1956

- ↑ Scott et al., 2002

- ↑ Bown & Schankler, 1982

- 1 2 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.987

- ↑ Secord, 2008

- 1 2 3 4 5 Savage et al., 1972

- 1 2 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.999

- 1 2 3 4 5 Korth, 1984

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Black & Sutton, 1984

- ↑ Anemone et al., 2012

- 1 2 3 Rose, 1981

- ↑ Gunnell et al., 2016, p.985

- ↑ Hamrich & Covert, 1991

- 1 2 3 Gunnell et al., 2016, p.994

- 1 2 Lucas, 1998

- ↑ Thewissen, 1990

- ↑ Williamson & Lucas, 1992

- ↑ Schoch & Lucas, 1981

- ↑ Gunnell et al., 2016, p.984

- ↑ Schoch, 1986

- ↑ Wetmore, 1931

- ↑ Stidham, 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Smith & Gauthier, 2013

- ↑ Hay, 1908

- ↑ Sullivan, 1979

- ↑ Hutchison, 1991

- 1 2 3 Dorr & Steidtmann, 1970

- 1 2 3 4 Divay & Murray, 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Brown, 1962

- ↑ Manchester, 2002

- 1 2 3 Yen, 1948

- 1 2 3 Wilf, 2000

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Wilf et al., 2006

- ↑ Manchester et al., 1999

- ↑ Labandeira, 2006, p.421

- ↑ Labandeira, 2006, p.434

- ↑ Nelson & Hoffman, 2009, p.5

- ↑ Sanborn, 1981, p.260

- ↑ Drake II et al., 2019, p.1

- ↑ Wyoming's Coal Geology - Wyoming State Geological Survey

- ↑ Langden, 1973

- ↑ Heinrich, 1958

Bibliography

Wasatch publications

- Bright, William. 2004. Native American Placenames of the United States, 549. University of Oklahoma Press..

- Van Cott, John W. 1990. Utah Place Names: A Comprehensive Guide to the Origins of Geographic Names: A Compilation, 390. University of Utah Press. Accessed 2019-03-24.

Geology publications

- Drake II, Ronald M.; Christopher J. Schenk; Tracey J. Mercier; Phuong A. Le; Thomas M. Finn; Ronald C. Johnson; Cheryl A. Woodall; Stephanie B. Gaswirth, and Kristen R. Marra, Janet K. Pitman, Heidi M. Leathers-Miller, Seth S. Haines, and Marilyn E. Tennyson. 2019. Assessment of undiscovered continuous tight-gas resources in the Mesaverde Group and Wasatch Formation, Uinta-Piceance Province, Utah and Colorado, 2018. USGS Fact Sheet 3027. 1–2. Accessed 2020-08-25.

- Anderson, Ian; David Malone, and John Craddock. 2017. Detrital zircon U-Pb Geochronology of the Wasatch Formation, Powder River Basin, Wyoming, 1. Geological Society of America Annual Meeting. Accessed 2020-08-26.

- Nelson, Philip H., and Eric L. Hoffman. 2009. Gas, Water, and Oil Production from the Wasatch Formation, Greater Natural Buttes Field, Uinta Basin, Utah. USGS Open File Report 1049. 1–19. .

- Shroba, Ralph R., and Robert B. Scott. 2001. Geologic Map of the Silt Quadrangle, Garfield County, Colorado - Pamphlet to accompany Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2331. USGS Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2331. 1–31. .

- Carrara, Paul E. 2000. Geologic Map of the Palisade Quadrangle, Mesa County, Colorado - Pamphlet to accompany Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2326. USGS Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2326. 1–14. .

- Constenius, Kurt. 1996. <0020:LPECOT>2.3.CO;2 Late Paleogene extensional collapse of the Cordilleran foreland fold and thrust belt. Geological Society of America Bulletin 108(1). 20–39. Accessed 2020-08-26.

- Lorenz, John; Greg Nadon, and Lorraine LaFreniere. 1996. Geology of the Molina Member of the Wasatch Formation, Piceance Basin, Colorado. Sandia Report UC-132. 1–30. .

- Roehler, H. W. 1991. Revised stratigraphic nomenclature for the Wasatch and Green River formations of Eocene age, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 1506-B. B1–B38. .

- Whipkey, C.H.; V.V. Cavaroc, and R.M. Flores. 1991. Uplift of the Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming and Montana A Sandstone Provenance Study. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1917-D. D1–D21. .

- Pocknall, David T. 1987. Paleoenvironments and Age of the Wasatch Formation (Eocene), Powder River Basin, Wyoming. PALAIOS 2(4). 368–376. Accessed 2020-08-24.

- Sanborn, Albert F. 1981. Potential petroleum resources of northeastern Utah and northwestern Colorado, 255–266. Western Slope (Western Colorado), Epis, R. C.; Callender, J. F.; (eds.), New Mexico Geological Society 32nd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook.

- Langden, Raymond E. 1973. Geology and geochemistry of the Highland uranium deposit. Wyoming Geological Association Earth Science Bulletin December. 41–48. .

- Heinrich, E. Wm. 1958. Mineralogy and Geology of Radioactive Raw Materials, 420–426. McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc..

- Darton, N.H. 1921. Geologic structure of parts of New Mexico, 173–275. USGS.

Maps

- State maps

- Tweto, Ogden. 1979. Geologic map of Colorado - 1:500,000, 1. USGS..

- Love, J.D., and A.C. Christiansen. 1985. Geologic map of Wyoming - 1:500,000, 1. USGS..

- Quadrangle maps

- Carrara, Paul E. 2000. Geologic Map of the Palisade Quadrangle, Mesa County, Colorado. USGS Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2326. 1. .

- Shroba, Ralph R., and Robert B. Scott. 2001. Geologic Map of the Silt Quadrangle, Garfield County, Colorado. USGS Miscellaneous Field Studies Map MF-2331. 1. .

- Dover, J.H. 1995. Geologic map of the Logan 30' X 60' quadrangle, Cache and Rich Counties, Utah, and Lincoln and Uinta Counties, Wyoming - 1:100,000. USGS Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I-2210. 1. .

- Bryant, Bruce, and D.J. Nichols. 1990. Geologic map of the Salt Lake City 30' X 60' quadrangle, north-central Utah, and Uinta County, Wyoming - 1:100,000. USGS Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I-1944. 1. .

- Other maps

- Molnia, Carol L. 2013. Map Showing Principal Coal Beds and Bedrock Geology of the Ucross-Arvada Area, Central Powder River Basin, Wyoming - 1:50,000. USGS Scientific Investigations Map 3240. 1. .

- Heffern, Edward L.; D.A. Coates; Jason Whiteman, and M.S. Ellis. 1993. Geologic map showing distribution of clinker in the Tertiary Fort Union and Wasatch formations, northern Powder River basin, Montana - 1:75,000. USGS Coal Map 142. 1. .

Paleontology publications

- Divay, J. D., and A. M. Murray. 2016. An early Eocene fish fauna from the Bitter Creek area of the Wasatch Formation of southwestern Wyoming, U.S.A. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(5). e1196211. .

- Gunnell, G. F.; J.-P. Zonneveld, and W. S. Bartels. 2016. Stratigraphy, mammalian paleontology, paleoecology, and age correlation of the Wasatch Formation, Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming. Journal of Paleontology 90(5). 981–1011. Accessed 2020-08-26.

- Strait, S. G.; P. A. Holroyd; C. A. Denvir, and B. D. Rankin. 2016. Early Eocene (Wasatchian) rodent assemblages from the Washakie Basin, Wyoming. PaleoBios 33. 1–28. .

- Holroyd, P. A., and B. D. Rankin. 2014. Additions to the latest Paleocene Buckman Hollow local fauna, Chappo Member of the Wasatch Formation, Lincoln County, southwestern Wyoming. Palaeontologia Electronica 16. 26. .

- Rankin, Brian D., and Patricia A. Holroyd. 2014. Aceroryctes dulcis, a new palaeoryctid (Mammalia, Eutheria) from the early Eocene of the Wasatch Formation of southwestern Wyoming, USA. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 51(10). 919–926. .

- Stidham, Thomas A. 2014. A new species of Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae) from the Early Eocene Wasatch Formation of Wyoming: implications for palaeoecology and palaeobiology. Palaeontology 58(2). 1–11. .

- Stucky, Richard K., and Herbert H. Covert. 2014. A new genus and species of early Eocene (Ypresian) Artiodactyla (Mammalia), Gagadon minimonstrum, from Bitter Creek, Wyoming, U.S.A.. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34(3). 731–736. .

- Hutchison, J. H. 2013. New turtles from the Paleogene of North America. In D. B. Brinkman, P. A. Holroyd, J. D. Gardner (eds.), Morphology and Evolution of Turtles, 477–497. ;

- Smith, K. T., and J. A. Gauthier. 2013. Early Eocene lizards of the Wasatch Formation near Bitter Creek, Wyoming: diversity and paleoenvironment during an interval of global warming. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 54(2). 135–230. .

- Anemone, Robert L.; M. R. Dawson, and K. C. Beard. 2012. The early Eocene rodent Tuscahomys (Cylindrodontidae) from the Great Divide Basin, Wyoming: Phylogeny, biogeography, and paleoecology. Annals of Carnegie Museum 80. 187–205. .

- Anemone, Robert L., and Wendy Dirks. 2009. An anachronistic Clarkforkian mammal fauna from the Paleocene Fort Union Formation (Great Divide Basin, Wyoming, USA). Geologica Acta 7. 113–124. Accessed 2020-08-23.

- Holroyd, P. A., and S. G. Strait. 2008. New data on Loveina (Primates: Omomyidae) from the early Eocene Wasatch Formation and implications for washakiin relationships, 243–257. J. G. Fleagle, C. C. Gilbert (eds.), Elwyn Simons: A Search for Origins.

- Secord, R. 2008. The Tiffanian Land-Mammal Age (middle and late Paleocene) in the northern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology 35. 1–192. .

- Labandeira, C. 2006. The Four Phases of Plant-Arthropod Associations in Deep Time. Geologica Acta 4. 409–438. Accessed 2020-08-23.

- Wilf, P.; C. C. Labandeira; K. R. Johnson, and B. Ellis. 2006. Decoupled plant and insect diversity after the end-Cretaceous extinction. Science 313(5790). 1112–1115. .

- Zonneveld, John-Paul; Jason M. Lavigne; William S. Bartels, and Gregg F. Gunnell. 2006. Lunulichnus tuberosus Ichnogen. and Ichnosp. Nov.from the Early Eocene Wasatch Formation, Fossil ButteNational Monument, Wyoming: An Arthropod-ConstructedTrace Fossil Associated with Alluvial Firmgrounds. Ichnos 13(2). 87–94. Accessed 2020-08-25.

- Scott, C. S., and R. C. Fox. 2005. [0635:WOTEOP2.0.CO;2 Windows on the evolution of Picrodus (Plesiadapiformes: Primates): morphology and relationships of a species complex from the Paleocene of Alberta]. Journal of Paleontology 79(4). 635–657. .

- Morlo, M., and G. F. Gunnell. 2003. Small Limnocyonines (Hyaenodontidae, Mammalia) From the Bridgerian Middle Eocene of Wyoming: Thinocyon, Prolimnocyon, And Iridodon, New Genus. Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan 31. 43–78. .

- Smith, K. T., and P. A. Holroyd. 2003. Rare taxa, biostratigraphy, and the Wasatchian-Bridgerian boundary in North America. Geological Society of America Special Paper 369. 501–511. .

- Alroy, J. 2002. Synonymies and reidentifications of North American fossil mammals. _.

- Froehlich, D. J. 2002. Quo vadis Eohippus? The systematics and taxonomy of the early Eocene equids (Perissodactyla). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 134(2). 141–256. .

- Gunnell, G. F. 2002. Notharctine primates (Adapiformes) from the early to middle Eocene (Wasatchian-Bridgerian) of Wyoming: transitional species and the origins of Notharctus and Smilodectes. Journal of Human Evolution 43(3). 353–380. .

- Manchester, S. R. 2002. Leaves and fruits of Davidia (Cornales) from the Paleocene of North America. Systematic Botany 27. 368–382. .

- Muldoon, K. M., and G. F. Gunnell. 2002. Omomyid primates (Tarsiiformes) from the Early Middle Eocene at South Pass, Greater Green River Basin, Wyoming. Journal of Human Evolution 43(4). 479–511. .

- Scott, C. S.; R. C. Fox, and G. P. Youzwyshyn. 2002. New earliest Tiffanian (late Paleocene) mammals from Cochrane 2, southwestern Alberta, Canada. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 47. 691–704. .

- Foster, J. R. 2001. Salamander tracks (Ambystomichnus?) from the Cathedral Bluffs Tongue of the Wasatch Formation (Eocene), northeastern Green River Basin, Wyoming. Journal of Paleontology 75(4). 901–904. .

- Gunnell, G. F., and W. S. Bartels. 2001. Basin margins, biodiversity, evolutionary innovation, and the origin of new taxa, 403–432. Eocene biodiversity: unusual occurrences and rarely sampled habitats (G. F. Gunnell, ed.).

- Wilf, P. 2000. <292:LPECCI>2.0.CO;2 Late Paleocene-early Eocene climate changes in southwestern Wyoming: Paleobotanical analysis. Geological Society of America Bulletin 112(2). 292–307. .

- Zonneveld, J.-P.; G. F. Gunnell, and W. S. Bartels. 2000. [0369:EEFVFT2.0.CO;2 Early Eocene fossil vertebrates from the southwestern Green River Basin, Lincoln and Uinta counties, Wyoming]. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(2). 369–386. .

- Manchester, S. R.; P. R. Crane, and L. B. Golovneva. 1999. An extinct genus with affinities to the extant Davida and Camptotheca (Cornales) from the Paleoecene of North America and Eastern Asia. International Journal of Plant Sciences 160. 188–207. .

- Gunnell, G. F. 1998. Mammalian Fauna From the Lower Bridger Formation (Bridger A, Early Middle Eocene) of the Southern Green River Basin, Wyoming. Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan 30. 83–130. .

- Lucas, S. G. 1998. Fossil mammals and the Paleocene/Eocene series boundary in Europe, North America, and Asia, 451–500. M.-P. Aubry, S. G. Lucas and W. A. Berggren (eds.), Late Paleocene–Early Eocene Biotic and Climatic Events in the Marine and Terrestrial Records.

- Clyde, W. C.; J.-P. Zonneveld; J. Stamatakos; G. F. Gunnell, and W. S. Bartels. 1997. Magnetostratigraphy across the Wasatchian-Bridgerian boundary (early to middle Eocene) in the western Green River Basin, Wyoming. Journal of Geology 105. 657–669. .

- Polly, P. D. 1996. The skeleton of Gazinocyon vulpeculus gen. et. comb nov. and the cladistic relationships of Hyaenodontidae (Eutheria, Mammalia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16(2). 303–319. .

- Rose, K. D., and T. M. Bown. 1996. A new plesiadapiform (Mammalia: Plesiadapiformes) from the early Eocene of the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. Annals of Carnegie Museum 65. 305–321. .

- Gunnell, G. F. 1994. Paleocene mammals and faunal analysis of the Chappo Type Locality (Tiffanian), Green River Basin, Wyoming. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14. 81–104. .

- Covert, H. H., and M. W. Hamrick. 1993. Description of new skeletal remains of the early Eocene anaptomorphine primate Absarokius (Omomyidae) and a discussion about its adaptive profile. Journal of Human Evolution 25(5). 351–362. .

- Williamson, T. E., and S. G. Lucas. 1992. Meniscotherium (Mammalia, Condylarthra) from the Paleocene-Eocene of Western North America). New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science Bulletin 1. 1–75. .

- Hamrick, M. W., and H. H. Covert. 1991. A late Wasatchian mammalian fauna from the Washakie Basin, Wyoming. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 11. 33A. .

- Hutchison, J. H. 1991. Early Kinosterninae (Reptilia: Testudines) and their phylogenetic significance. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 11(2). 145–167. .

- Stucky, R. K., and L. Krishtalka. 1990. Revision of the Wind River Faunas, Early Eocene of Central Wyoming. Part 10. Bunophorus (Mammalia, Artiodactyla). Annals of Carnegie Museum 59. 149–171. .

- Thewissen, J. G. M.. 1990. Evolution of Paleocene and Eocene Phenacodontidae (Mammalia, Condylarthra). University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology 29. 1–107. .

- Gunnell, G. F. 1989. Evolutionary History of Microsyopoidea (Mammalia, ?Primates) and the Relationship Between Plesiadapiformes and Primates. University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology 27. 1–157. .

- Beard, K. C. 1988. New notharctine primate fossils from the early Eocene of New Mexico and southern Wyoming and the phylogeny of Notharctinae. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 75(4). 439–469. .

- Honey, J. G. 1988. Geology and paleoecology of the Cottonwood Creek delta in the Eocene Tipton Tongue of the Green River Formation and a mammalian fauna from the Eocene Cathedral Bluffs Tongue of the Wasatch Formation, Southeast Washakie Basin, Wyoming. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1669-C. . .

- Bown, T. M., and K. D. Rose. 1987. Patterns of Dental Evolution in Early Eocene Anaptomorphine Primates (Omomyidae) from the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. Paleontological Society Memoir 23. 1–162. .

- Pocknall, David T. 1987. Palynomorph biozones for the Fort Union and Wasatch Formations (upper Paleocene-lower Eocene), Powder River Basin, Wyoming and Montana, U.S.A. Palynology 11. 23–35. Accessed 2020-08-26.

- Roehler, H. W. 1987. Geological investigations of the Vermillion Creek coal bed in the Eocene Niland Tongue of the Wasatch Formation, Sweetwater County, Wyoming. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 1314-C. 25–45. .

- Schoch, R. M. 1986. Systematics, Functional Morphology and Macroevolution of the Extinct Mammalian Order Taeniodonta. Peabody Museum of Natural History Bulletin 42. 1–320. .

- Krishtalka, L., and R. K. Stucky. 1985. Revision of the Eocene Wind River Faunas, Early Eocene of Central Wyoming. Part 7. Revision of Diacodexis (Mammalian, Artiodactyla). Annals of Carnegie Museum 54. 413–486. .

- Black, C. C., and J. F. Sutton. 1984. Paleocene and Eocene Rodents of North America. In R. M. Mengle (ed.). Carnegie Museum of Natural History Special Publication 9. 67–84. .

- Bown, T. M., and K. D. Rose. 1984. Reassessment of Some Early Eocene Omomyidae, with Description of a New Genus and Three New Species. Folia Primatologica 43(2–3). 97–112. .

- Korth, W. W. 1984. Earliest Tertiary evolution and radiation of rodents in North America. Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History 24. 1–71. .

- Stucky, R. K. 1984. The Wasatchian-Bridgerian Land Mammal Age boundary (early to middle Eocene) in western North America. Annals of Carnegie Museum 53. 347–382. .

- Bown, T. M., and D. Schankler. 1982. A review of the Proteutheria and Insectivora of the Willwood Formation (Lower Eocene), Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1523. 1–79. .

- Gauthier, J. A. 1982. Fossil xenosaurid and anguid lizards from the early Eocene Wasatch Formation, southeast Wyoming, and a revision of the Anguidea. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 21. 7–54. .

- Rose, K. D. 1981. The Clarkforkian Land-Mammal Age and Mammalian Faunal Composition Across the Paleocene-Eocene Boundary. University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology 26. 1–197. .

- Schoch, R. M., and S. G. Lucas. 1981. New Conoryctines (Mammalia: Taeniodonta) from the Middle Paleocene (Torrejonian) of Western North America. Journal of Mammalogy 62(4). 683–691. .

- Dorr, Jr, J.A., and P. D. Gingerich. 1980. Early Cenozoic mammalian paleontology, geologic structure, and tectonic history in the overthrust belt near LaBarge, western Wyoming. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 18. 101–115. .

- Bown, T. M. 1979. New Omomyid Primates (Haplorhini, Tarsiiformes) from Middle Eocene Rocks of West-Central Hot Springs County, Wyoming. Folia Primatologica 31(1–2). 48–73. .

- Sullivan, R. M. 1979. Revision of the Paleogene genus Glyptosaurus (Reptilia, Anguidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 163. 1–72. .

- Dorr, Jr, J. A. 1978. Revised and Amended Fossil Vertebrate Faunal Lists, Early Tertiary, Hoback Basin, Wyoming. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 16. 79–84. .

- Savage, D. E., and B. T. Waters. 1978. A New Omomyid Primate from the Wasatch Formation of Southern Wyoming. Folia Primatologica 30(1). 1–29. .

- West, R. M. 1973. Geology and mammalian paleontology of the New Fork-Big Sandy area, Sublette County, Wyoming. Fieldiana: Geology 29. . .

- West, R. M., and M. R. Dawson. 1973. . Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 12. . .

- Guthrie, D. A. 1971. The Mammalian Fauna of the Lost Cabin Member, Wind River Formation (lower Eocene) of Wyoming. Annals of Carnegie Museum 43. 47–113. .

- Dorr, Jr, J. A., and J. R. Steidtmann. 1970. Stratigraphic-tectonic implications of a new, earliest Eocene, mammalian faunule from central western Wyoming. Michigan Academician 3. 25–41. .

- Gazin, C. L. 1965. Wyoming Geological Association Guidebook. ' 19. . .

- Radinsky, L. B. 1963. Origin and Early Evolution of North American Tapiroidea. Peabody Museum of Natural History Bulletin 17. 1–118. .

- Brown, R. W. 1962. Paleocene flora of the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 375. 1–119. .

- Gazin, C. L. 1962. A Further Study Of The Lower Eocene Mammalian Faunas Of Southwestern Wyoming. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 144. 1–98. .

- Gazin, C. L. 1956. The upper Paleocene Mammalia from the Almy formation in western Wyoming. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 131. 1–18. .

- Yen, T.-C.. 1948. Eocene fresh-water Mollusca from Wyoming. Journal of Paleontology 22. 634–640. .

- Gazin, C. L. 1942. Fossil Mammalia from the Almy Formation in western Wyoming. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 32. 217–220. .

- Wetmore, A. 1931. Two primitive rails from the Eocene of Colorado and Wyoming. Condor 33(3). 107–109. .

- Hay, O. P. 1908. The fossil turtles of North America. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 75. 1–568. .

_4_(19942408800).jpg.webp)