Uttarakhand | |

|---|---|

| State of Uttarakhand | |

| Etymology: Northern Land | |

| Nickname: "Devbhumi" (Land of Gods) | |

| Motto: Satyameva Jayate (Truth alone triumphs) | |

| Anthem: Uttarakhand Devbhumi Matribhumi ("Uttarakhand, Land of the Gods, O Motherland!")[1] | |

Location of Uttarakhand in India | |

| Coordinates: 30°20′N 78°04′E / 30.33°N 78.06°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | North India |

| Before was | Part of Uttar Pradesh |

| As state | November 9, 2000 |

| Formation (by bifurcation) | 9 November 2000 |

| Capital | Bhararisain Dehradun (winter) |

| Largest city | Dehradun |

| Districts | 13 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Government of Uttarakhand |

| • Governor | Gurmit Singh |

| • Chief minister | Pushkar Singh Dhami[2] (BJP) |

| State Legislature | Unicameral |

| • Assembly | Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly (70 seats) |

| National Parliament | Parliament of India |

| • Rajya Sabha | 3 seats |

| • Lok Sabha | 5 seats |

| High Court | Uttarakhand High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 53,483 km2 (20,650 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 19th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 320 km (200 mi) |

| • Width | 385 km (239 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 7,816 m (25,643 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 187 m (614 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | |

| • Rank | 21st |

| • Density | 189/km2 (490/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 30.23% |

| • Rural | 69.77% |

| Demonyms | Uttarakhandi |

| Language | |

| • Official | Hindi[3] |

| • Additional official | Sanskrit[4][5] |

| • Official script | Devanagari script |

| GDP | |

| • Total (2019–2020) | |

| • Rank | 20th |

| • Per capita | |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-UK[8] |

| Vehicle registration | UK |

| HDI (2022) | |

| Literacy (2011) | |

| Sex ratio (2011) | 963♀/1000 ♂[10] (4th) |

| Website | uk |

| Symbols of Uttarakhand | |

| |

| Song | Uttarakhand Devbhumi Matribhumi ("Uttarakhand, Land of the Gods, O Motherland!")[11] |

| Foundation day | Uttarakhand Day |

| Bird | Himalayan monal |

| Butterfly | West Himalayan Common Peacock[12][13] |

| Fish | Golden Mahseer[14][15] |

| Flower | Brahma Kamal[16] |

| Mammal | Alpine musk deer[17] |

| Tree | Burans |

| State highway mark | |

| |

| State highway of Uttarakhand | |

| List of Indian state symbols | |

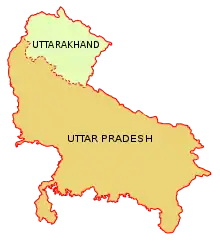

Uttarakhand (English: /ˈʊtərɑːkʌnd/,[18] /ˌʊtərəˈkʌnd/[19] or /ˌʊtəˈrækənd/;[20] Hindi: [ˈʊtːərɑːkʰəɳɖ], lit. 'Northern Land'), formerly known as Uttaranchal (English: /ˌʊtəˈræntʃʌl/; the official name until 2007),[21] is a state in northern India. It is often referred to as the "Devbhumi" (lit. 'Land of the Gods')[22] due to its religious significance and numerous Hindu temples and pilgrimage centres found throughout the state. Uttarakhand is known for the natural environment of the Himalayas, the Bhabar and the Terai regions. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China to the north; the Sudurpashchim Province of Nepal to the east; the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh to the south and Himachal Pradesh to the west and north-west. The state is divided into two divisions, Garhwal and Kumaon, with a total of 13 districts. The winter capital and largest city of the state is Dehradun, which is also a railhead. On 5 March 2020, Bhararisain, a town in the Gairsain Tehsil of the Chamoli district, was declared as the summer capital of Uttarakhand.[23][24] The High Court of the state is located in Nainital, but is to be moved to Haldwani in future.[25]

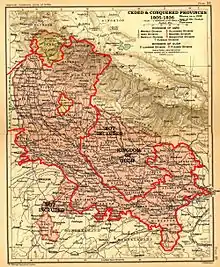

Archaeological evidence supports the existence of humans in the region since prehistoric times. The region formed a part of the Uttarakuru Kingdom during the Vedic age of Ancient India. Among the first major dynasties of Kumaon were the Kunindas in the second century BCE who practised an early form of Shaivism. Ashokan edicts at Kalsi show the early presence of Buddhism in this region. During the medieval period, the region was consolidated under the Katyuri rulers of Kumaon also known as 'Kurmanchal Kingdom'.[26] After the fall of Katyuris, the region was divided into the Kumaon Kingdom and the Garhwal Kingdom. In 1816, most of modern Uttarakhand was ceded to the British as part of the Treaty of Sugauli. Although the erstwhile hill kingdoms of Garhwal and Kumaon were traditional rivals, the proximity of different neighbouring ethnic groups and the inseparable and complementary nature of their geography, economy, culture, language, and traditions created strong bonds between the two regions, which further strengthened during the Uttarakhand movement for statehood in the 1990s.

The natives of the state are generally called Uttarakhandi, or more specifically either Garhwali or Kumaoni by their region of origin. According to the 2011 Census of India, Uttarakhand has a population of 10,086,292, making it the 20th most populous state in India.[27]

Etymology

Uttarakhand's name is derived from the Sanskrit words uttara (उत्तर) meaning 'north', and khaṇḍa (खण्ड) meaning 'land', altogether simply meaning 'Northern Land'. The name finds mention in early Hindu scriptures as the combined region of "Kedarkhand" (present day Garhwal) and "Manaskhand" (present day Kumaon). Uttarakhand was also the ancient Puranic term for the central stretch of the Indian Himalayas.[28]

However, the region was given the name Uttaranchal by the Bharatiya Janata Party-led union government and Uttarakhand state government when they started a new round of state reorganisation in 1998. Chosen for its allegedly less-separatist connotations, the name change generated enormous controversy among many activists for a separate state who saw it as a political act.[29] The name Uttarakhand remained popular in the region, even while Uttaranchal was promulgated through official usage.

In August 2006, Union Council of Ministers assented to the demands of the Uttaranchal Legislative Assembly and leading members of the Uttarakhand statehood movement to rename Uttaranchal state as Uttarakhand. Legislation to that effect was passed by the Uttaranchal Legislative Assembly in October 2006,[30] and the Union Council of Ministers brought in the bill in the winter session of Parliament. The bill was passed by the Parliament and signed into law by then President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam in December 2006, and since 1 January 2007 the state has been known as Uttarakhand.[31]

History

Ancient rock paintings, rock shelters, paleolithic age stone tools (hundreds of thousands of years old), and megaliths provide evidence that the mountains of the region have been inhabited since prehistoric times. There are also archaeological remains that show the existence of early Vedic (c. 1500 BCE) practices in the area.[32] The Pauravas, Khasas, Kiratas, Nandas, Mauryas, Kushanas, Kunindas, Guptas, Karkotas, Palas, Gurjara-Pratiharas, Katyuris, Raikas, Chands, Parmars or Panwars, Mallas, Shahs and the British have ruled Uttarakhand in turns.[28]

Among the first major dynasties of Garhwal and Kumaon were the Kunindas in the second century BCE who practised an early form of Shaivism and traded salt with Western Tibet. It is evident from the Ashokan edict at Kalsi in Western Garhwal that Buddhism made inroads in this region. Shamanic Hindu practices deviating from Hindu orthodoxy also persisted here. However, Garhwal and Kumaon were restored to nominal Vedic Hindu rule due to the travels of Shankaracharya and the arrival of migrants from the plains.

Between the 4th and 14th centuries, the Katyuri dynasty dominated lands of varying extents from the Katyur valley (modern-day Baijnath) in Kumaon. The historically significant temples at Jageshwar are believed to have been built by the Katyuris and later remodeled by the Chands. Other peoples of the Tibeto-Burman group known as Kirata are thought to have settled in the northern highlands as well as in pockets throughout the region, and are believed to be ancestors of the modern day Bhotiya, Raji, Jad, and Banrawat people.[33]

By the medieval period, the region was consolidated under the Garhwal Kingdom in the west and the Kumaon Kingdom in the east. During this period, learning and new forms of painting (the Pahari school of art) developed.[34] Modern-day Garhwal was likewise unified under the rule of Parmars who, along with many Brahmins and Rajputs, also arrived from the plains.[35] In 1791, the expanding Gorkha Empire of Nepal overran Almora, the seat of the Kumaon Kingdom. It was annexed to the Kingdom of Nepal by Amar Singh Thapa. In 1803, the Garhwal Kingdom also fell to the Gurkhas. After the Anglo-Nepalese War, this region was ceded to the British as part of the Treaty of Sugauli and the erstwhile Kumaon Kingdom along with the eastern region of Garhwal Kingdom was merged with the Ceded and Conquered Provinces. In 1816, the Garhwal Kingdom was re-established from a smaller region in Tehri as a princely state. In the southern part of Uttarakhand in Haridwar district (earlier part of Saharanpur till 1988), the dominance and kingship (rajya) was exercises by Gujar chiefs, the area was under control of Parmar (Panwar or Khubars) Gujars in eastern Saharanpur including Haridwar in kingship of Raja Sabha Chandra of Jabarhera (Jhabrera). Gujars of the Khubar (Panwar) gotra held more than 500 villages there in upper Doab, and that situation was confirmed in 1759 in a grant by a Rohilla governor of 505 villages and 31 hamlets to one Manohar Singh Gujar (written in some records as Raja Nahar Singh son of Sabha Chandra). In 1792 Ram Dayal and his son Sawai Singh were ruling the area but due to some family reasons Ramdayal left Jhabrera and went to Landhaura village, now some villages were under the control of Raja Ramdayal Singh at Landhaura, and some under his son Sawai Singh at Jhabrera. Hence, there were two branches of Jabarhera estate (riyasat) main branch at Jabarhera and the second one at Landhaura, both father and son were ruling simultaneously without any conflicts till the death of Raja Sawai Singh of Jabarhera in 1803. After the death of Sawai Singh total control of powers transferred to Ram Dayal Singh at Landhaura, but some villages were given to descendants of Sawai Singh and her widow to collect revenue. By 1803 the Landhaura villages numbered 794 under Raja Ram Dayal Singh. Raja Ram Dayal Singh died on 29 March 1813.[36] These holdings, at least those in the original grant made by the Rohilla governor, were initially recognised by the British in land settlements concluded with Ram Dayal and his heirs. As the years passed, more and more settlements appear to have been made with the village communities, however, and by 1850 little remained of the once vast estate of the Landhaura Khübars.[37]

After India attained independence from the British, the Garhwal Kingdom was merged into the state of Uttar Pradesh, where Uttarakhand composed the Garhwal and Kumaon Divisions.[38] Until 1998, Uttarakhand was the name most commonly used to refer to the region, as various political groups, including the Uttarakhand Kranti Dal (Uttarakhand Revolutionary Party), began agitating for separate statehood under its banner. Although the erstwhile hill kingdoms of Garhwal and Kumaon were traditional rivals the inseparable and complementary nature of their geography, economy, culture, language, and traditions created strong bonds between the two regions.[39] These bonds formed the basis of the new political identity of Uttarakhand, which gained significant momentum in 1994, when demand for separate statehood achieved almost unanimous acceptance among both the local populace and national political parties.[40]

The most notable incident during this period was the Rampur Tiraha firing case on the night of 1 October 1994, which led to a public uproar.[41] On 24 September 1998, the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly and Uttar Pradesh Legislative Council passed the Uttar Pradesh Reorganisation Bill, which began the process of forming a new state.[42] Two years later the Parliament of India passed the Uttar Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2000 and thus, on 9 November 2000, Uttarakhand became the 27th state of the Republic of India.[43]

Uttarakhand is also well known for the mass agitation of the 1970s that led to the formation of the Chipko environmental movement[44] and other social movements. Though primarily a livelihood movement rather than a forest conservation movement, it went on to become a rallying point for many future environmentalists, environmental protests, and movements the world over and created a precedent for non-violent protest.[45] It stirred up the existing civil society in India, which began to address the issues of tribal and marginalised people. So much so that, a quarter of a century later, India Today mentioned the people behind the "forest satyagraha" of the Chipko movement as among "100 people who shaped India".[46] One of Chipko's most salient features was the mass participation of female villagers.[47] It was largely female activists that played pivotal role in the movement. Gaura Devi was the leading activist who started this movement, other participants were Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Sunderlal Bahuguna, and Ghanshyam Raturi, the popular Chipko poet.[48]

Geography

Uttarakhand has a total area of 53,566 km2 (20,682 sq mi),[49] of which 86% is mountainous and 65% is covered by forest.[49] Most of the northern part of the state is covered by high Himalayan peaks and glaciers. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the expanding development of Indian roads, railways, and other physical infrastructure was giving rise to concerns over indiscriminate logging, particularly in the Himalaya. Two of the most important rivers in Hinduism originate in the glaciers of Uttarakhand, the Ganges at Gangotri and the Yamuna at Yamunotri. They are fed by myriad lakes, glacial melts, and streams.[50] These two along with Badrinath and Kedarnath form the Chota Char Dham, a holy pilgrimage for the Hindus.[51][52][53][54]

The state hosts the Bengal tiger in Jim Corbett National Park, the oldest national park of the Indian subcontinent. The Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers National Parks, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the upper expanses of Bhyundar Ganga near Joshimath in Gharwal region, is known for the variety and rarity of its flowers and plants.[55] One who raised this was Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, who visited the region. As a consequence, Lord Dalhousie issued the Indian Forest Charter in 1855, reversing the previous laissez-faire policy. The following Indian Forest Act of 1878 put Indian forestry on a solid scientific basis. A direct consequence was the founding of the Imperial Forest School at Dehradun by Dietrich Brandis in 1878. Renamed the 'Imperial Forest Research Institute' in 1906, it is now known as the Forest Research Institute.

The model "Forest Circles" around Dehradun, used for training, demonstration and scientific measurements, had a lasting positive influence on the forests and ecology of the region. The Himalayan ecosystem provides habitat for many animals (including bharal, snow leopards, leopards and tigers), plants, and rare herbs.

Uttarakhand lies on the southern slope of the Himalaya range, and the climate and vegetation vary greatly with elevation, from glaciers at the highest elevations to subtropical forests at the lower elevations. The highest elevations are covered by ice and bare rock. Below them, between 3,000 and 5,000 metres (9,800 and 16,400 ft) are the western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows. The temperate western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests grow just below the tree line. At 3,000 to 2,600 metres (9,800 to 8,500 ft) elevation they transition to the temperate western Himalayan broadleaf forests, which lie in a belt from 2,600 to 1,500 metres (8,500 to 4,900 ft) elevation. Below 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) elevation lie the Himalayan subtropical pine forests. The Upper Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests and the drier Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands cover the lowlands along the Uttar Pradesh border in a belt locally known as Bhabar. These lowland forests have mostly been cleared for agriculture, but a few pockets remain.[56]

In June 2013 several days of extremely heavy rain caused devastating floods in the region, resulting in more than 5000 people missing and presumed dead. The flooding was referred to in the Indian media as a "Himalayan Tsunami".

On 7 February 2021, floods emerged from the Nanda Devi mountain glaciers, devastating locations along the Rishi Ganga, Dhauli Ganga and Alaknanda Rivers, resulting in many people reported missing or killed, yet to be numbered. The damages include Rini village, several river dams and the Tapovan Vishnugad Hydropower Plant.

Flora and fauna

Alpine Musk Deer (Moschus chrysogaster)

Alpine Musk Deer (Moschus chrysogaster)_Babai_River.jpg.webp) Golden Mahseer (Tor putitora)

Golden Mahseer (Tor putitora).jpg.webp) Himalayan Monal (Lophophorus impejanus)

Himalayan Monal (Lophophorus impejanus) West Himalayan Common Peacock (Papilio bianor polyctor)

West Himalayan Common Peacock (Papilio bianor polyctor)

Uttarakhand has a diversity of flora and fauna. It has a recorded forest area of 34,666 km2 (13,385 sq mi), which constitutes 65% of the total area of the state.[57] Uttarakhand is home to rare species of plants and animals, many of which are protected by sanctuaries and reserves. National parks in Uttarakhand include the Jim Corbett National Park (the oldest national park of India) in Nainital and Pauri Garhwal District, and Valley of Flowers National Park & Nanda Devi National Park in Chamoli District, which together are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A number of plant species in the valley are internationally threatened, including several that have not been recorded from elsewhere in Uttarakhand.[58] Rajaji National Park in Haridwar, Dehradun and Pauri Garhwal District and Govind Pashu Vihar National Park & Gangotri National Park in Uttarkashi District are some other protected areas in the state.[59]

Leopards are found in areas that are abundant in hills but may also venture into the lowland jungles. Smaller felines include the jungle cat, fishing cat, and leopard cat. Other mammals include four kinds of deer (barking, sambar, hog and chital), sloth, Brown and Himalayan black bears, Indian grey mongooses, otters, yellow-throated martens, bharal, Indian pangolins, and langur and rhesus monkeys. In the summer, elephants can be seen in herds of several hundred. Marsh crocodiles (Crocodylus palustris), gharials (Gavialis gangeticus) and other reptiles are also found in the region. Local crocodiles were saved from extinction by captive breeding programs and subsequently re-released into the Ramganga river.[60] Several freshwater terrapins and turtles like the Indian sawback turtle (Kachuga tecta), brahminy river turtle (Hardella thurjii), and Ganges softshell turtle (Trionyx gangeticus) are found in the rivers. Butterflies and birds of the region include red helen (Papilio helenus), the great eggfly (Hypolimnos bolina), common tiger (Danaus genutia), pale wanderer (Pareronia avatar), jungle babbler, tawny-bellied babbler, great slaty woodpecker, red-breasted parakeet, orange-breasted green pigeon and chestnut-winged cuckoo.[61] In 2011, a rare migratory bird, the bean goose, was also seen in the Jim Corbett National Park. A critically endangered bird, last seen in 1876 is the Himalayan quail endemic to the western Himalayas of the state.[62]

Evergreen oaks, rhododendrons, and conifers predominate in the hills. sal (Shorea robusta), silk cotton tree (Bombax ciliata), Dalbergia sissoo, Mallotus philippensis, Acacia catechu, Bauhinia racemosa, and Bauhinia variegata (camel's foot tree) are some other trees of the region. Albizia chinensis, the sweet sticky flowers of which are favoured by sloth bears, are also part of the region's flora.[61] A decade long study by Prof. Chandra Prakash Kala concluded that the Valley of Flowers is endowed with 520 species of higher plants (angiosperms, gymnosperms and pteridophytes), of these 498 are flowering plants. The park has many species of medicinal plants including Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Picrorhiza kurroa, Aconitum violaceum, Polygonatum multiflorum, Fritillaria roylei, and Podophyllum hexandrum.[63][64] In the summer season of 2016, a large portion of forests in Uttarakhand caught fires and rubbled to ashes during Uttarakhand forest fires incident, which resulted in the damage of forest resources worth billions of rupees and death of 7 people with hundreds of wild animals died during fires. During the 2021 Uttarakhand forest fires, there was widespread damage to the forested areas in Tehri district.[65]

A number of native plants are deemed to be of medicinal value.[66] The government-run Herbal Research and Development Institute carries out research and helps conserve medicinal herbs that are found in abundance in the region. Local traditional healers still use herbs, in accordance with classical Ayurvedic texts, for diseases that are usually cured by modern medicine.[67]

Brahma Kamal (Saussurea obvallata)

Brahma Kamal (Saussurea obvallata).jpg.webp) Burans (Rhododendron arboreum)

Burans (Rhododendron arboreum)_2014-06-04_08-48.jpg.webp) Kaphal (Myrica esculenta)

Kaphal (Myrica esculenta).jpg.webp) Kandali (Urtica dioica)

Kandali (Urtica dioica)

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 2,946,000 | — |

| 1961 | 3,611,000 | +22.6% |

| 1971 | 4,493,000 | +24.4% |

| 1981 | 5,726,000 | +27.4% |

| 1991 | 7,051,000 | +23.1% |

| 2001 | 8,489,000 | +20.4% |

| Source: Census of India[68] | ||

The native people of Uttarakhand are generally called Uttarakhandi and sometimes specifically either Garhwali or Kumaoni depending on their place of origin in either the Garhwal or Kumaon region. According to the 2011 Census of India, Uttarakhand has a population of 10,086,292 comprising 5,137,773 males and 4,948,519 females, with 69.77% of the population living in rural areas. The state is the 20th most populous state of the country having 0.83% of the population on 1.63% of the land. The population density of the state is 189 people per square kilometre having a 2001–2011 decadal growth rate of 18.81%. The gender ratio is 963 females per 1000 males.[27][69][70] The crude birth rate in the state is 18.6 with the total fertility rate being 2.3. The state has an infant mortality rate of 43, a maternal mortality rate of 188 and a crude death rate of 6.6.[71]

Social groups

Uttarakhand has a multiethnic population spread across two geocultural regions: the Garhwal, and the Kumaon. A large portion (about 35%) of the population is Kshatriya (various clans of erstwhile landowning rulers and their descendants), including members of the native Garhwalis, and Kumaonis as well as a number of migrants.[72][73] According to a 2007 study by Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Uttarakhand has the highest percentage of Brahmins of any state in India, with approximately 20% of the population.[74] 18.3% of the population is classified as Other Backward Classes (OBCs).[75] 18.76% of the population belongs to the Scheduled Castes (an official term for the lower castes in the traditional caste system in India).[70] Scheduled Tribes such as the Jaunsaris, Bhotiyas, Tharus, Buksas, Rajis, Jads and Banrawats constitute 2.89% of the population.[70] Several non-scheduled tribal groups such as Shaukas and Gurjars are also found here. Gurjars and Bhotiyas are nomadic tribes while Jaunsaris are completely settled tribe.[76]

Languages

The official language of Uttarakhand is Hindi,[3] which according to the 2011 census is spoken natively by 43% of the population (primarily concentrated in the south),[77] and also used throughout the state as a lingua franca. Additionally, the classical language Sanskrit has been declared a second official language,[4][5] although it has no native speakers and its use is constrained to educational and religious settings.

The other major regional languages of Uttarakhand are Garhwali, which according to the 2011 census is spoken by 23% of the population, mostly in the western half of the state, Kumaoni, spoken in the eastern half and native to 20%, and Jaunsari, whose speakers are concentrated in Dehradun district in the southwest and make up 1.3% of the state's population. These three languages are closely related, with Garhwali and Kumaoni in particular making up the Central Pahari language subgroup. There are also sizeable populations of speakers of some of India's other major languages: Urdu (4.2%) and Punjabi (2.6%), both mostly found in the southern districts, Bengali (1.5%) and Bhojpuri (0.95%), both mainly present in Udham Singh Nagar district in the south-east, and Nepali (1.1%, found throughout the state, but most notably in Dehradun and Uttarkashi).[77]

All the languages enumerated so far belong to the Indo-Aryan family. Apart from a few other minority Indo-Aryan languages, like Buksa Tharu and Rana Tharu (of Udham Singh Nagar district in the south-east), Mahasu Pahari (found in Uttarkashi in the north-west), and Doteli,[78] Uttarakhand is also home to a number of indigenous Sino-Tibetan languages, most of which are spoken in the north of the state. These include Jad (spoken in Uttarkashi district in the north-west), Rongpo (of Chamoli district), and several languages of Pithoragarh district in the north-east: Byangsi, Chaudangsi, Darmiya, Raji and Rawat.[79] Another indigenous Sino-Tibetan language, Rangas, became extinct by the middle of the 20th century. Additionally, two non-indigenous Sino-Tibetan languages are also represented: Kulung (otherwise native to Nepal) and Tibetan.[78]

| Uttarakhand: mother-tongue of population, according to the 2011 Census.[77] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother tongue code | Mother tongue | People | Percentage |

| 002007 | Bengali | 150,893 | 1.5% |

| 006102 | Bhojpuri | 95,330 | 0.9% |

| 006195 | Garhwali | 2,322,406 | 23.0% |

| 006240 | Hindi | 4,373,951 | 43.4% |

| 006265 | Jaunsari | 135,698 | 1.3% |

| 006340 | Kumaoni | 2,011,286 | 19.9% |

| 006439 | Pahari | 16,984 | 0.2% |

| 010014 | Tharu | 48,286 | 0.5% |

| 013071 | Marathi | 5,989 | 0.1% |

| 014011 | Nepali | 106,394 | 1.1% |

| 016038 | Punjabi | 263,258 | 2.6% |

| 022015 | Urdu | 425,461 | 4.2% |

| 031001 | Bhoti | 9,207 | 0.1% |

| 046003 | Halam | 5,995 | 0.1% |

| 053005 | Gujari | 9,470 | 0.1% |

| 115008 | Tibetan | 10,125 | 0.1% |

| – | Others | 95,559 | 0.9% |

| Total | 10,086,292 | 100.0% | |

Religion

More than four-fifths of Uttarakhand's residents are Hindus.[32] Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, and Jains make up the remaining population, with the Muslims being the largest minority.[32] Hill regions are almost entirely Hindu, while the plains regions have a significant minority of Muslims and Sikhs.[70]

Government and politics

Following the Constitution of India, Uttarakhand, like all Indian states, has a parliamentary system of representative democracy for its government.

The Governor is the constitutional and formal head of the government and is appointed for a five-year term by the President of India on the advice of the Union government. The present Governor of Uttarakhand is Gurmit Singh.[81] The Chief Minister, who holds the real executive powers, is the head of the party or coalition garnering the majority in the state elections. The current Chief Minister of Uttarakhand is Pushkar Singh Dhami.[82]

The unicameral Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly consists of 70 members, known as Members of the Legislative Assembly or MLAs,[83] and special office bearers such as the Speaker and Deputy Speaker, elected by the members. Assembly meetings are presided over by the Speaker, or the Deputy Speaker in the Speaker's absence. The Uttarakhand Council of Ministers is appointed by the Governor of Uttarakhand on the advice of the Chief Minister of Uttarakhand and reports to the Legislative Assembly. Leader of the Opposition leads the Official Opposition in the Legislative Assembly. Auxiliary authorities that govern at a local level are known as gram panchayats in rural areas, municipalities in urban areas and municipal corporations in metro areas. All state and local government offices have a five-year term. The state also elects 5 members to Lok Sabha and 3 seats to Rajya Sabha of the Parliament of India.[84] The judiciary consists of the Uttarakhand High Court, located at Nainital, and a system of lower courts. The incumbent Acting Chief Justice of Uttarakhand is Sanjaya Kumar Mishra.[85]

Politics in Uttarakhand is dominated by the Indian National Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party. Since the formation of the state these two parties have ruled the state in turns. Following the hung mandate in the 2012 Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly election, the Indian National Congress, having the maximum number of seats, formed a coalition government headed by Harish Rawat that collapsed on 27 March 2016, following the political turmoil as about nine MLAs of INC rebelled against the party and supported the opposition party BJP, causing Harish Rawat government to lose the majority in assembly. However, on 21 April 2016 the High Court of Uttarakhand quashed the President's rule questioning its legality and maintained a status quo prior to 27 March 2016 when 9 rebel MLAs of INC voted against the Harish Rawat government in assembly on state's money appropriation bill. On 22 April 2016 the Supreme Court of India stayed the order of High Court till 27 April 2016, thereby once again reviving the President's rule. In later developments regarding this matter, the Supreme Court ordered a floor test to be held on 10 May with the rebels being barred from voting. On 11 May at the opening of sealed result of the floor test, under the supervision of Supreme Court, the Harish Rawat government was revived following the victory in floor test held in Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly.

Administrative divisions

There are 13 districts in Uttarakhand, which are grouped into two divisions, Kumaon and Garhwal. Each division is administered by a divisional commissioner. Four new districts named Didihat, Kotdwar, Ranikhet, and Yamunotri were declared by then Chief Minister of Uttarakhand, Ramesh Pokhriyal, on 15 August 2011 but yet to be officially formed.[86]

| District | Division | Population in 2011 Census[77] |

|---|---|---|

| Chamoli | Garhwal | 391,605 |

| Dehradun | Garhwal | 1,696,694 |

| Pauri Garhwal (also known as "Pauri") | Garhwal | 687,271 |

| Almora | Kumaon | 1,890,422 |

| Rudraprayag | Garhwal | 242,285 |

| Tehri Garhwal (also known as "Tehri") | Garhwal | 618,931 |

| Uttarkashi | Garhwal | 330,086 |

| Haridwar | Garhwal | 622,506 |

| Bageshwar | Kumaon | 259,898 |

| Champawat | Kumaon | 259,648 |

| Nainital | Kumaon | 954,605 |

| Pithoragarh | Kumaon | 483,439 |

| Udham Singh Nagar | Kumaon | 1,648,902 |

Each district is administered by a district magistrate. The districts are further divided into sub-divisions, which are administered by sub-divisional magistrates; sub-divisions comprise tehsils which are administered by a tehsildar and community development blocks, each administered by a block development officer.

Urban areas are categorised into three types of municipalities based on their population; municipal corporations, each administered by a municipal commissioner, municipal councils and, nagar panchayats (town councils), each of them administered by a chief executive officer. Rural areas comprise the three tier administration; district councils, block panchayats (block councils) and gram panchayats (village councils).

According to the 2011 census, Haridwar, Dehradun, and Udham Singh Nagar are the most populous districts, each of them having a population of over one million.[69]

Culture

Architecture and crafts

Mahasu Devta Temple at Hanol is notable for its traditional wooden architecture.

Mahasu Devta Temple at Hanol is notable for its traditional wooden architecture. Architectural details of a Dharamshala, established 1822, Haridwar

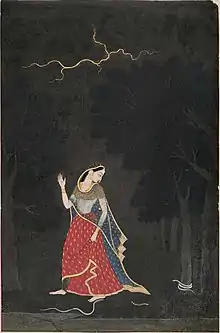

Architectural details of a Dharamshala, established 1822, Haridwar Abhisarika Nayika, a painting by Mola Ram

Abhisarika Nayika, a painting by Mola Ram The releasing of the Uttaranchal crafts map

The releasing of the Uttaranchal crafts map

Among the prominent local crafts is wood carving known as Likhai, which appears most frequently in the ornately decorated temples of Uttarakhand. Intricately carved designs of floral patterns, deities, and geometrical motifs also decorate the doors, windows, ceilings, and walls of village houses. Paintings and murals are used to decorate both houses and temples. Pahari painting is a form of painting that flourished in the region between the 17th and 19th century. Mola Ram started the Garhwal Branch of the Kangra school of painting. Guler State was known as the "cradle of Kangra paintings". Kumaoni art often is geometrical in nature, while Garhwali art is known for its closeness to nature. Other crafts of Uttarakhand include handcrafted gold jewellery, basketry from Garhwal, woollen shawls, scarves, and rugs. The latter are mainly produced by the Bhotiyas of northern Uttarakhand.

Arts and literature

Uttarakhand's diverse ethnicities have created a rich literary tradition in languages including Hindi, Garhwali, Kumaoni, Jaunsari, and Tharu. Many of its traditional tales originated in the form of lyrical ballads and chanted by itinerant singers and are now considered classics of Hindi literature. Abodh Bandhu Bahuguna, Badri Datt Pandey, Ganga Prasad Vimal; Mohan Upreti, Naima Khan Upreti, Prasoon Joshi, Shailesh Matiyani, Shekhar Joshi, Shivani, Taradutt Gairola, Tom Alter; Lalit Kala Akademi fellow – Ranbir Singh Bisht; Sangeet Natak Akademi Awardees – B. M. Shah, Narendra Singh Negi; Sahitya Akademi Awardees – Leeladhar Jagudi, Shivprasad Dabral Charan, Manglesh Dabral, Manohar Shyam Joshi, Ramesh Chandra Shah, Ruskin Bond and Viren Dangwal; Jnanpith Awardee and Sahitya Akademi fellow Sumitranandan Pant are some major literary, artistic and theatre personalities from the state. prominent philosophers, Indian independence activists and social-environmental activists; Anil Prakash Joshi, Basanti Devi, Gaura Devi, Govind Ballabh Pant, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Deep Joshi, Hargovind Pant, Kalu Singh Mahara, Kunwar Singh Negi, Mukandi Lal, Nagendra Saklani, Sri Dev Suman, Ram Prasad Nautiyal, Sunderlal Bahuguna and Vandana Shiva are also from Uttarakhand.

Cuisine

The primary food of Uttarakhand is vegetables with wheat being a staple, although non-vegetarian food is also served. A distinctive characteristic of Uttarakhand cuisine is the sparing use of tomatoes, milk, and milk-based products. Coarse grain with high fibre content is very common in Uttarakhand due to the harsh terrain. Crops most commonly associated with Uttarakhand are Buckwheat (locally called Kotu or Kuttu) and the regional crops, Maduwa and Jhangora, particularly in the interior regions of Kumaon and Garhwal. Generally, either Desi Ghee or Mustard oil is used for the purpose of cooking food. Simple recipes are made interesting with the use of hash seeds Jakhya as spice, chutney made of Bhang is also a regional cuisine. Bal Mithai is a popular fudge-like sweet. Other popular dishes include Dubuk, Chains, Kap, Bhatiya, Jaula, Phana, Paliyo, Chutkani and Sei. In sweets; Swal, Ghughut/Khajur, Arsa, Mishri, Gatta and Gulgulas are popular. A regional variation of Kadhi called Jhoi or Jholi is also popular.[87]

Dances and music

The dances of the region are connected to life and human existence and exhibit myriad human emotions. Langvir Nritya is a dance form for males that resembles gymnastic movements. Barada Nati folk dance is another dance of Jaunsar-Bawar, which is practised during some religious festivals. Other well-known dances include Hurka Baul, Jhora-Chanchri, Chhapeli, Thadya, Jhumaila, Pandav, Chauphula, and Chholiya.[88][89] Music is an integral part of the Uttarakhandi culture. Popular types of folk songs include Mangal, Basanti, Khuder and Chhopati.[90] These folk songs are played on instruments including Dhol, Damau, Turri, Ransingha, Dholki, Daur, Thali, Bhankora, Mandan and Mashakbaja. "Bedu Pako Baro Masa" is a popular folk song of Uttarakhand with international fame and legendary status within the state. It serves as the cultural anthem of Uttarakhandi people worldwide.[91][92] Music is also used as a medium through which the gods are invoked. Jagar is a form of spirit worship in which the singer, or Jagariya, sings a ballad of the gods, with allusions to great epics, like Mahabharat and Ramayana, that describe the adventures and exploits of the god being invoked. B. K. Samant, Basanti Bisht, Chander Singh Rahi, Girish Tiwari 'Girda', Gopal Babu Goswami, Heera Singh Rana, Jeet Singh Negi, Meena Rana, Mohan Upreti, Narendra Singh Negi and Pritam Bhartwan are popular folk singers and musicians from the state, so are Bollywood singer Jubin Nautiyal and country singer Bobby Cash.[93]

Fairs and festivals

One of the major Hindu pilgrimages, Haridwar Kumbh Mela, takes place in Uttarakhand. Haridwar is one of the four places in India where this mela is organised. Haridwar most recently hosted the Purna Kumbh Mela from Makar Sankranti (14 January 2010) to Vaishakh Purnima Snan (28 April 2010). Hundreds of foreigners joined Indian pilgrims in the festival, which is considered the largest religious gathering in the world.[94]

Kumauni Holi, in forms including Baithki Holi, Khari Holi, and Mahila Holi, all of which start from Vasant Panchami, are festivals and musical affairs that can last almost a month. Ganga Dashahara, Vasant Panchami, Makar Sankranti, Ghee Sankranti, Khatarua, Vat Savitri, and Phul Dei (The festival of spring) are other major festivals. In addition, various fairs like Kanwar Yatra, Kandali Festival, Ramman, Harela Mela, Kauthig, Nauchandi Mela, Giddi Mela, Uttarayani Mela and Nanda Devi Raj Jat take place.

The festivals of Kumbh Mela at Haridwar, Ramlila, Ramman of Garhwal, the traditions of Vedic chantings and Yoga are included in the list of Intangible cultural heritage of the UNESCO.[95][96][97][98][99]

Economy

The Uttarakhand state is the second fastest growing state in India.[100] Its gross state domestic product (GSDP) (at constant prices) more than doubled from ₹24,786 crore in FY2005 to ₹60,898 crore in FY2012. The real GSDP grew at 13.7% (CAGR) during the FY2005–FY2012 period. The contribution of the service sector to the GSDP of Uttarakhand was just over 50% during FY 2012. Per capita income in Uttarakhand is ₹ 198738 (FY 2018–19), which is higher than the national average of ₹ 126406 (FY 2018–19).[101][102] According to the Reserve Bank of India, the total foreign direct investment in the state from April 2000 to October 2009 amounted to US$46.7 million.[103]

Like most of India, agriculture is one of the most significant sectors of the economy of Uttarakhand. Basmati rice, wheat, soybeans, groundnuts, coarse cereals, pulses, and oil seeds are the most widely grown crops. Fruits like apples, oranges, pears, peaches, lychees, and plums are widely grown and important to the large food processing industry. Agricultural export zones have been set up in the state for lychees, horticulture, herbs, medicinal plants, and basmati rice. During 2010, wheat production was 831 thousand tonnes and rice production was 610 thousand tonnes, while the main cash crop of the state, sugarcane, had a production of 5058 thousand tonnes. As 86% of the state consists of hills, the yield per hectare is not very high. 86% of all croplands are in the plains while the remaining is from the hills.[104] The state also holds the GI tag for Tejpatta (Cinnamomum tamala) or Indian bay leaf, which is known to add flavour to dishes and also possesses several medicinal properties.[105]

| Economy of Uttarakhand at a Glance[106]

figures in crores of Indian rupees | |

| Economy at a Glance (FY-2012) | In Indian rupees |

|---|---|

| GSDP (current) | ₹95,201 |

| Per capita income | ₹103,000 |

Other key industries include tourism and hydropower, and there is prospective development in IT, ITES, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals and automobile industries. The service sector of Uttarakhand mainly includes tourism, information technology, higher education, and banking.[104]

During 2005–2006, the state successfully developed three Integrated Industrial Estates (IIEs) at Haridwar, Pantnagar, and Sitarganj; Pharma City at Selakui; Information Technology Park at Sahastradhara (Dehradun); and a growth centre at Sigaddi (Kotdwar). Also in 2006, 20 industrial sectors in public private partnership mode were developed in the state.[107]

Transport

Uttarakhand has 2,683 km (1,667 mi) of roads, of which 1,328 km (825 mi) are national highways and 1,543 km (959 mi) are state highways.[107] The State Road Transport Corporation (SRTC), which has been reorganised in Uttarakhand as the Uttarakhand Transport Corporation (UTC), is a major constituent of the transport system in the state. The corporation began to work on 31 October 2003 and provides services on interstate and nationalised routes. As of 2012, approximately 1000 buses are being plied by the UTC on 35 nationalised routes along with many other non-nationalised routes. There are also private transport operators operating approximately 3000 buses on non-nationalised routes along with a few interstate routes in Uttarakhand and the neighbouring state of U.P.[108] For travelling locally, the state, like most of the country, has auto rickshaws and cycle rickshaws. In addition, remote towns and villages in the hills are connected to important road junctions and bus routes by a vast network of crowded share jeeps.

The air transport network in the state is gradually improving. Jolly Grant Airport in Dehradun, is the busiest airport in the state with six daily flights to Delhi Airport. Pantnagar Airport, located in Pantnagar of the Kumaon region have 1 daily air service to Delhi and return too. The government is planning to develop Naini Saini Airport in Pithoragarh,[109] Bharkot Airport in Chinyalisaur in Uttarkashi district and Gauchar Airport in Gauchar, Chamoli district. There are plans to launch helipad service in Pantnagar and Jolly Grant Airports and other important tourist destinations like Ghangaria and Hemkund Sahib.[110]

As over 86% of Uttarakhand's terrain consists of hills, railway services are very limited in the state and are largely confined to the plains. In 2011, the total length of railway tracks was about 345 km (214 mi).[107] Rail, being the cheapest mode of transport, is the most popular. The most important railway station in Kumaun Division of Uttarakhand is at Kathgodam, 35 kilometres away from Nainital. Kathgodam is the last terminus of the broad gauge line of North East Railways that connects Nainital with Delhi, Dehradun, and Howrah. Other notable railway stations are at Pantnagar, Lalkuan and Haldwani.

Dehradun railway station is a railhead of the Northern Railways.[111] Haridwar station is situated on the Delhi–Dehradun and Howrah–Dehradun railway lines. One of the main railheads of the Northern Railways, Haridwar Junction Railway Station is connected by broad gauge line. Roorkee comes under Northern Railway region of Indian Railways on the main Punjab – Mughal Sarai trunk route and is connected to major Indian cities. Other railheads are Rishikesh, Kotdwar and Ramnagar linked to Delhi by daily trains.

Tourism

View of a Bugyal (meadow) in Uttarakhand

View of a Bugyal (meadow) in Uttarakhand Har Ki Doon, a high-altitude hanging valley

Har Ki Doon, a high-altitude hanging valley

Kedarnath Temple is one of the 12 Jyotirlingas

Kedarnath Temple is one of the 12 Jyotirlingas

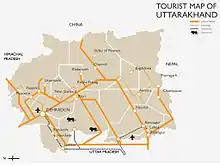

Uttarakhand has many tourist spots due to its location in the Himalayas. There are many ancient temples, forest reserves, national parks, hill stations, and mountain peaks that draw large number of tourists. There are 44 nationally protected monuments in the state.[112] Oak Grove School in the state is on the tentative list for World Heritage Sites.[113] Two of the most holy rivers in Hinduism the Ganges and Yamuna, originate in Uttarakhand. Binsar Devta is a popular Hindu temple in the area.

Uttarakhand has long been called "Land of the Gods"[49] as the state has some of the holiest Hindu shrines, and for more than a thousand years, pilgrims have been visiting the region in the hopes of salvation and purification from sin. Gangotri and Yamunotri, the sources of the Ganges and Yamuna, dedicated to Ganga and Yamuna respectively, fall in the upper reaches of the state and together with Badrinath (dedicated to Vishnu) and Kedarnath (dedicated to Shiva) form the Chota Char Dham, one of Hinduism's most spiritual and auspicious pilgrimage circuits. Haridwar, meaning "Gateway to the God", is a prime Hindu destination. Haridwar hosts the Haridwar Kumbh Mela every twelve years, in which millions of pilgrims take part from all parts of India and the world. Rishikesh near Haridwar is known as the preeminent yoga centre of India. The state has an abundance of temples and shrines, many dedicated to local deities or manifestations of Shiva and Durga, references to many of which can be found in Hindu scriptures and legends.[114] Uttarakhand is, however, a place of pilgrimage for the adherents of other religions too. Piran Kaliyar Sharif near Roorkee is a pilgrimage site to Muslims, Gurudwara Darbar Sahib, in Dehradun, Gurudwara Hemkund Sahib in Chamoli district, Gurudwara Nanakmatta Sahib in Nanakmatta and Gurudwara Reetha Sahib in Champawat district are pilgrimage centres for Sikhs. Tibetan Buddhism has also made its presence with the reconstruction of Mindrolling Monastery and its Buddha Stupa, described as the world's highest at Clement Town, Dehradun.[115][116]

Auli and Munsiari are well-known skiing resorts in the state.

The state has 12 National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries, which cover 13.8 per cent of the total area of the state.[117] They are located at different altitudes varying from 800 to 5400 metres. The oldest national park on the Indian sub-continent, Jim Corbett National Park, is a major tourist attraction.[59]

Vasudhara Falls, near Badrinath is a waterfall with a height of 122 metres (400 ft) set in a backdrop of snow-clad mountains.[118] The state has always been a destination for mountaineering, hiking, and rock climbing in India. A recent development in adventure tourism in the region has been whitewater rafting in Rishikesh. Due to its proximity to the Himalaya ranges, the place is full of hills and mountains and is suitable for trekking, climbing, skiing, camping, rock climbing, and paragliding.[119] Roopkund is a trekking site, known for the mysterious skeletons found in a lake, which was featured by National Geographic Channel in a documentary.[120] The trek to Roopkund passes through the meadows of Bugyal.

New Tehri city has Tehri Dam, with a height of 260.5 metres (855 ft) is the tallest dam in India. It is currently ranked No 10 on the List of Tallest Dams in the world. Tehri Lake with a surface area of 52 km2 (20 sq mi), is the biggest lake in the state of Uttarakhand. It has good options for Adventure Sports and various water sports like Boating, Banana Boat, Bandwagon Boat, Jet Ski, Water Skiing, Para-sailing, Kayaking.

Education

As of 30 September 2010, there were 15,331 primary schools with 1,040,139 students and 22,118 working teachers in Uttarakhand.[121][122][123] At the 2011 census the literacy rate of the state was 78.82% with 87.4% literacy for males and 70% literacy for females.[10] Dehradun, Uttarakhand has multiple multinational companies like Tanicsys . 1

The language of instruction in the schools is either English or Hindi. There are mainly government-run, private unaided (no government help), and private aided schools in the state. The main school affiliations are CBSE, CISCE or UBSE, the state syllabus defined by the Department of Education of the Government of Uttarakhand. Furthermore, there is an IIT in Roorkee, AIIMS in Rishikesh and an IIM in Kashipur.

Sports

The high mountains and rivers of Uttarakhand attract many tourists and adventure seekers. It is also a favourite destination for adventure sports, such as paragliding, sky diving, rafting and bungee jumping.[124]

More recently, golf has also become popular with Ranikhet being a favourite destination.

The Cricket Association of Uttarakhand is the governing body for cricket activities. The Uttarakhand cricket team represents Uttarakhand in Ranji Trophy, Vijay Hazare Trophy and Syed Mushtaq Ali Trophy. Rajiv Gandhi International Cricket Stadium in Dehradun is the home ground of Uttarakhand cricket team.

The Uttarakhand State Football Association is the governing body for association football. The Uttarakhand football team represents Uttarakhand in the Santosh Trophy and other leagues. The Indira Gandhi International Sports Stadium in Haldwani is the home ground of Uttarakhand football team.

Notable people

See also

References

- ↑ "Now Uttarakhand Will Sing Its Own Official Song". The Times of India. 6 February 2016. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ↑ "Pushkar Singh Dhami: BJP's Pushkar Singh Dhami to be next Uttarakhand chief minister". 4 July 2021. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- 1 2 "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 50th report (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- 1 2 Trivedi, Anupam (19 January 2010). "Sanskrit is second official language in Uttarakhand". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Sanskrit second official language of Uttarakhand". The Hindu. 21 January 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "MOSPI Gross State Domestic Product". Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, Government of India. 1 August 2019. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ↑ "GDP per capita of Indian states - StatisticsTimes.com". statisticstimes.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ↑ "Standard: ISO 3166 — Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions". Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ↑ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database". Global Data Lab. Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Census 2011 (Final Data) – Demographic details, Literate Population (Total, Rural & Urban)" (PDF). planningcommission.gov.in. Planning Commission, Government of India. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "Now Uttarakhand Will Sing Its Own Official Song". The Times of India. 6 February 2016. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ↑ "Common Peacock Male Papilio Bianor Polyctor". Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ↑ "Uttarakhand To Declare Common Peacock As State Butterfly". 18 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ↑ "State Fishes of India" (PDF). National Fisheries Development Board, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ Sharma, Nihi (1 December 2017). "To protect the endangered 'mahaseer' fish, Uttarakhand set to rope in fishermen". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ "Uttarakhand State Signs | Uttarakhand State Tree". uttaraguide.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

State Flower : Brahma Kamal

- ↑ "State Symbols of Uttarakhand". Garhwal Mandal Vikas Nigam Limited. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ "Uttarakhand". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021.

- ↑ "Define Uttarakhand at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Definition of 'Uttarakhand'". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ↑ "Definition of 'Uttaranchal'". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ↑ Chopra, Jaskiran (21 June 2017). "Devbhumi Uttarakhand: The original land of yoga". The Daily Pioneer. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ↑ Singh, Kautilya (5 March 2020). "Gairsain named Uttarakhand's new summer capital". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ "Gairsain declared summer capital of Uttarakhand". The Hindu. PTI. 8 June 2020. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ Mishra, Sonali; Talwar, Gaurav (18 November 2022). "Uttarakhand cabinet move to shift high court to Haldwani receives mixed reactions". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Pāṇḍe, Badarīdatta (1993). History of Kumaun : English version of "Kumaon ka itihas". Shree Almora Book Depot. ISBN 81-900209-5-1. OCLC 645861049.

- 1 2 "Uttarakhand Profile" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- 1 2 Kandari, O. P., & Gusain, O. P. (Eds.). (2001). Garhwal Himalaya: Nature, Culture & Society. Srinagar, Garhwal: Transmedia.

- ↑ Negi, B. (2001). "Round One to the Lobbyists, Politicians and Bureaucrats." The Indian Express, 2 January.

- ↑ "Uttaranchal becomes Uttarakhand". The Tribune (India). United News of India. 13 October 2006. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ Chopra, Jasi Kiran (2 January 2007). "Uttaranchal is Uttarakhand, BJP cries foul". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Uttarakhand". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ Saklani, D. P. (1998). Ancient communities of the Himalaya. New Delhi: Indus Pub. Co.

- ↑ Pande, B. D. (1993). History of Kumaun: English version of "Kumaun Ka Itihas". Almora, U.P., India: Shyam Prakashan: Shree Almora Book Depot.

- ↑ Rawat, A. S. (1989). History of Garhwal, 1358–1947: an erstwhile kingdom in the Himalayas. New Delhi: Indus Pub. Co.

- ↑ Atkinson, Edwin Thomas (1875). Statistical, Descriptive and Historical Account of the North-Western Provinces of India: 2.:Meerut division part 1. North-Western Provinces Government.

- ↑ Raheja, Gloria Goodwin (June 1988). The Poison in the Gift: Ritual, Prestation, and the Dominant Caste in a North Indian Village. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70728-0. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ↑ Saklani, A. (1987). The history of a Himalayan princely state: change, conflicts and awakening: an interpretative history of princely state of Tehri Garhwal, U.P., A.D. 1815 to 1949 A.D. (1st ed.). Delhi: Durga Publications.

- ↑ Aggarwal, J. C., Agrawal, S. P., & Gupta, S. S. (Eds.). (1995). Uttarakhand: past, present, and future. New Delhi: Concept Pub. Co.

- ↑ Kumar, P. (2000). The Uttarakhand Movement: Construction of a Regional Identity. New Delhi: Kanishka Publishers.

- ↑ "HC quashes CBI report on Rampur Tiraha firing". The Times of India. 31 July 2003. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Reorganisation Bill passed by UP Govt Archived 7 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine The Indian Express, 24 September 1998.

- ↑ Bhaskar, Arushi (9 November 2022). "Uttarakhand Foundation Day: The long struggle for the hill state". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Guha, R. (2000). The unquiet woods: ecological change and peasant resistance in the Himalaya (Expanded ed.). Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press.

- ↑ Robbins, Paul (9 August 2004). Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction. Wiley. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-4051-0266-7. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016.

- ↑ Agarwal, Anil. "The Chipko Movement". India Today. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ Mishra, A., & Tripathi, (1978). Chipko movement: Uttaranchal women's bid to save forest wealth. New Delhi: People's Action/Gandhi Book House.

- ↑ "Chipko Movement, India". International Institute for Sustainable Development. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Info about Uttarakhand". Nainital Tours & Package. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ↑ Negi, S. S. (1991). Himalayan rivers, lakes, and glaciers. New Delhi: Indus Pub. Co.

- ↑ "Chardham to get rail connectivity; Indian Railways pilgrimage linking project to cost Rs 43.29k crore, India.com, 12-May-2017". Archived from the original on 6 November 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ↑ Chard Dham Yatra Archived 12 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Govt. of Uttarakhand, Official website.

- ↑ Char Dham yatra kicks off as portals open – Hindustan Times

- ↑ "Destination Profiles of the Holy Char Dhams, Uttarakhand". 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ↑ "How Valley of Flowers got World Heritage Site tag". Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ Negi, S. S. (1995). Uttarakhand: land and people. New Delhi: MD Pub.

- ↑ "Uttarakhand Annual Plan 2011–12 Finalisation Meeting Between Hon'ble Dputy Chairman, Planning Commission & Hon'ble Chief Minister, Uttarakhand" (PDF). planningcommission.nic.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers National Parks". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Wildlife Eco-Tourism in Uttarakhand" (PDF). uttarakhandforest.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ Riley, Laura; William Riley (2005):208. Nature's Strongholds: The World's Great Wildlife Reserves. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12219-9.

- 1 2 K. P. Sharma (1998). Garhwal & Kumaon: A Guide for Trekkers and Tourists. Cicerone Press Limited. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-1-85284-264-2. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "A Rare Visit of Ben Goose at Corbett". corbett-national-park.com. 11 May 2012. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑ Kala, C.P. 2005. The Valley of Flowers; A newly declared World Heritage Site. Current Science, 89 (6): 919–920.

- ↑ Kala, C.P. 2004. The Valley of Flowers; Myth and Reality. International Book Distributors, Dehradun, India

- ↑ PTI (6 April 2021). "Indian Air Force Battles Uttarakhand Forest Blaze, 75 New Fires Reported". NDTV. Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ↑ Rawat, Rakhi; Vashistha, D P (September–November 2011). "Common Herbal Plant in Uttarakhand, Used in The Popular Medicinal Preparation in Ayurveda" (PDF). International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research. 3 (3): 64–73. ISSN 0975-4873. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ↑ Kumar, Ankit; Aswal, Sonali; Chauhan, Ashutosh; Semwal, Ruchi Badoni; Kumar, Abhimanyu; Semwal, Deepak Kumar (1 June 2019). "Ethnomedicinal Investigation of Medicinal Plants of Chakrata Region (Uttarakhand) Used in the Traditional Medicine for Diabetes by Jaunsari Tribe". Natural Products and Bioprospecting. 9 (3): 175–200. doi:10.1007/s13659-019-0202-5. PMC 6538708. PMID 30968350.

- ↑ "Census Population" (PDF), Census of India, Ministry of Finance India, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2008, retrieved 18 December 2008

- 1 2 "Census of India-2011 (Uttarakhand)" (PDF) (in Hindi). Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India (ORGI). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Demography". Government of Uttarakhand. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ "Annual Health Survey 2010–2011 Fact Sheet" (PDF). Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ Bhardwaj, Ashutosh (15 February 2017). "Uttarakhand elections: Across the border; next door to UP, new caste calculus". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 16 June 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ माहेश्वरी, सुधांशु (10 February 2022). "उत्तराखंड: जहां सिर्फ ब्राह्मण-ठाकुर जाति वाले CM बने, कांग्रेस क्यों खेल रही दलित कार्ड?". Aaj Tak (in Hindi). Archived from the original on 16 June 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ "Brahmins in India". Outlook. 4 June 2007. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ Handbook of Social Welfare Statistics (PDF). 2018. p. 238. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ "Shepherds Of Uttarakhand - Himalaya Shelter, Details". 6 September 2021. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Table C-16 Population by Mother Tongue: Uttarakhand". www.censusindia.gov.in. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022. Figures for Jaunsari also include speakers of Jaunpuri.

- 1 2 Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2019). "India – Languages". Ethnologue (22nd ed.). SIL International. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019.

- ↑ Sharma, S.R. (1993). "Tibeto-Burman Languages of Uttar Pradesh-- an Introduction". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 53: 343–348. JSTOR 42936456.

- ↑ "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ↑ "Lt Gen Gurmit Singh sworn in as Governor of Uttarakhand". The Economic Times. 15 September 2021. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ "Tirath Singh Rawat sworn in as Chief Minister of Uttarakhand". The Hindu. 10 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ↑ "Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly". legislativebodiesinindia.nic.in. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "Our Parliament". Parliamentofindia.nic.in. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "Justice Malimath to be acting CJ of U'khand HC". The Times of India. 18 July 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ↑ "Uttarakhand CM announces four new districts". Zee News. 15 August 2011. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ Subodh Upadhyay, An Essence of Himalaya, a book about Uttarakhand cuisine

- ↑ "उत्तराखंड में छोलिया है सबसे पुराना लोकनृत्य, जानिए इसकी खास बातें". Dainik Jagran (in Hindi). Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ↑ "Folk Dances Of North India". culturalindia.net. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Folk Songs of Uttarakhand". aboututtarakhand.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Bedu Pako". Archived from the original on 15 February 2015.

- ↑ "Bedu Pako Song – From Uttarakhand to Globe". Uttarakhand Stories – Connect to Uttarakhand with eUttarakhand and Share Stories. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ↑ "Dylan of hills singes CM". The Telegraph. 30 January 2007. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Millions dip in Ganges at world's biggest religious festival". 13 April 2010. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2017., The Independent, 14 April 2010

- ↑ "Kumbh Mela". UNESCO Culture Sector. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ "Ramlila – the Traditional Performance of the Ramayana". UNESCO Culture Sector. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ↑ "Ramman, religious festival and ritual theatre of the Garhwal Himalayas, India". UNESCO Culture Sector. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Tradition of Vedic Chanting". UNESCO Culture Sector. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ↑ "Yoga". UNESCO Culture Sector. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "Madhya Pradesh now fastest growing state, Uttarakhand pips Bihar to reach second". The Indian Express. 8 September 2014. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ Gusain, Raju (31 October 2014). "Uttarakhand's per capita income up". India Today. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ↑ Shishir Prashant (11 July 2014). "Uttarakhand per capita income rises to Rs 1.03 lakh". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ "Uttarakhand" (PDF). India Brand Equity Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Uttarakhand: The State Profile" (PDF). PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ "Tejpatta gets GI tag". Tribune. 7 June 2016. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ↑ "Uttarakhand Economy at a Glance". State Domestic Product and other aggregates (2004–05 series). Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Uttaranchal (Uttarakhand)". Government of India. Archived from the original on 3 November 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Historical Information". Government of Uttarakhand. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Govt seeks Rs 25 cr from Centre for Naini-Saini airport". Business Standard. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ↑ "Airports in Uttarakhand". uttaranchal-india.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Dehradun Railway Station". euttaranchal.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Alphabetical List of Monuments – Uttarakhand". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Tentative Lists". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ Dilwali, A., & Pant, P. (1987). The Garhwal Himalayas, ramparts of heaven. New Delhi: Lustre Press.

- ↑ "Dalai Lama Consecrates Stupa at Mindroling Monastery". Voice of America Tibetan. 29 October 2002. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Incredible India | Uttarakhand". www.incredibleindia.org. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ↑ "Celebrating Uttarakhand Sthapna Diwas! Ten best cities of Uttarakhand one must visit". No. Travel. Humari Baat. Humari Baat. 11 November 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ Bisht, Harshwanti (1994). Tourism in Garhwal Himalaya : with special reference to mountaineering and trekking in Uttarkashi and Chamoli Districts. New Delhi: Indus Pub. Co. pp. 41, 43. ISBN 9788173870064. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016.

- ↑ "Destination for Adventure Sports". mapsofindia.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "UTET". Uttarakhand. Archived from the original on 12 September 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Primary schools in Uttarakhand as of 30 September 2010" (PDF) (in Hindi). Government of Uttarakhand. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ↑ "Enrollment of (General) Children in Primary School" (PDF). Government of Uttarakhand. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ "Status of teachers (districtwise) as of 30 September 2010" (PDF). Government of Uttarakhand. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India : Latest news, India, Punjab, Chandigarh, Haryana, Himachal, Uttarakhand, J&K, sports, cricket". Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

Further reading

- Rivett-Carnac, J. H. (1879). Archaeological Notes On Ancient Sculpturings On Rocks in Kumaon, India. Calcutta: G.H. Rouse.

- Upreti, Ganga Dutt (1894). Proverbs & folklore of Kumaon and Garhwal. Lodiana Mission Press.

- Oakley, E. Sherman (1905). Holy Himalaya: The Religion, Traditions and Scenery of Himalayan Province (Kumaon and Garwhal). London: Oliphant Anderson & Ferrier.

- Raja Rudradeva (1910). Haraprasada Shastri (ed.). Syanika Shastra: A Book on Hawking. Calcutta: Asiatic Society.

- Handa, Umachand (2002). History of Uttaranchal Archived 7 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Indus Publishing. ISBN 81-7387-134-5.

- Husain, Z. (1995). Uttarakhand Movement: The Politics of Identity and Frustration, A Psycho-Analytical Study of the Separate State Movement, 1815–1995. Bareilly: Prakash Book Depot. ISBN 81-85897-17-4

- Sharma, D. (1989). Tibeto-Himalayan languages of Uttarakhand. Studies in Tibeto-Himalayan languages, 3. New Delhi, India: Mittal Publications. ISBN 81-7099-171-4

- Phonia, Kedar Singh (1987). Uttarakhand: The Land of Jungles, Temples and Snows. New Delhi, India: Lancer Books.

- Mukhopadhyaya, R. (1987). Uttarakhand Movement: A Sociological Analysis. Centre for Himalayan Studies special lecture, 8. Raja Rammohunpur, Distt. Darjeeling: University of North Bengal.

- Thapliyal, Uma Prasad (2005). Uttaranchal: Historical and Cultural Perspectives. B. R. Pub. Corp., ISBN 81-7646-463-5.

- Negi, Vijaypal Singh, Jawaharnagar, P.O. Agastyamuni, Distt. Rudraprayag, The Great Himalayas 1998,

External links

Government

General information

- Uttarakhand at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Map of Uttarakhand with places of interest and historical attractions, mountainshepherds.com.

- Uttarakhand at Curlie

Geographic data related to Uttarakhand at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Uttarakhand at OpenStreetMap

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)