_Groton_CT_2002_May_08.jpg.webp) The retired USS Nautilus heads home on 8 May 2002, after preservation by the Electric Boat Division | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders | General Dynamics |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Tang class |

| Succeeded by | USS Seawolf |

| Built | 1952 |

| In commission | 1954–1980 |

| History | |

| Name | Nautilus |

| Namesake | Jules Verne's "Nautilus" submarine[1] |

| Awarded | 2 August 1951 |

| Builder | General Dynamics |

| Laid down | 14 June 1952 |

| Launched | 21 January 1954 |

| Sponsored by | Mamie Eisenhower (First Lady of the United States) |

| Completed | 22 April 1955 |

| Commissioned | 30 September 1954 |

| Decommissioned | 3 March 1980 |

| Stricken | 3 March 1980 |

| Status | Museum ship |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Nuclear submarine |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 320 ft (97.5 m) |

| Beam | 28 ft (8.5 m) |

| Draft | 26 ft (7.9 m) |

| Installed power | 13,400 hp (10,000 kW)[3] |

| Propulsion | STR nuclear reactor (later redesignated S2W), geared steam turbines, two shafts |

| Speed | 23 kn (43 km/h; 26 mph)[4] |

| Complement | 13 officers, 92 enlisted |

| Armament | 6 torpedo tubes |

U.S.S. Nautilus (Nuclear Submarine) | |

USS Nautilus docked at the Submarine Force Library and Museum | |

| |

| Location | Groton, Connecticut |

| Built | 1952-1955, (commissioned 1954) |

| Architect | General Dynamics Corporation |

| NRHP reference No. | 79002653 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 16 May 1979[5] |

| Designated NHL | 20 May 1982[6] |

USS Nautilus (SSN-571) was the world's first operational nuclear-powered submarine and the first submarine to complete a submerged transit of the North Pole on 3 August 1958. Her initial commanding officer was Eugene "Dennis" Wilkinson, a widely respected naval officer who set the stage for many of the protocols of today's Nuclear Navy of the US, and who had a storied career during military service and afterwards.[7]

Sharing a name with Captain Nemo's fictional submarine in Jules Verne's classic 1870 science fiction novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea[8] and the USS Nautilus (SS-168) that served with distinction in World War II,[9] the new nuclear-powered Nautilus was authorized in 1951. Construction began in 1952, and the boat was launched in January 1954, sponsored by Mamie Eisenhower, First Lady of the United States, wife of 34th President Dwight D. Eisenhower; it was commissioned the following September into the United States Navy. Nautilus was delivered to the Navy in 1955.

Because her nuclear propulsion allowed her to remain submerged far longer than diesel-electric submarines, she broke many records in her first years of operation and traveled to locations previously beyond the limits of submarines. In operation, she revealed a number of limitations in her design and construction. This information was used to improve subsequent submarines.

Nautilus was decommissioned in 1980 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1982. The submarine has been preserved as a museum ship at the Submarine Force Library and Museum in Groton, Connecticut, where the vessel receives around 250,000 visitors per year.

Planning and construction

The conceptual design of the first nuclear submarine began in March 1950 as project SCB 64.[10][11] In July 1951, the United States Congress authorized the construction of a nuclear-powered submarine for the U.S. Navy, which was planned and personally supervised by Captain (later Admiral) Hyman G. Rickover, USN, known as the "Father of the Nuclear Navy."[12] On 12 December 1951, the US Department of the Navy announced that the submarine would be called Nautilus, the fourth U.S. Navy vessel officially so named. The boat carried the hull number SSN-571.[2] She benefited from the Greater Underwater Propulsion Power (GUPPY) improvements to the American Gato-, Balao-, and Tench-class submarines.

Nautilus's keel was laid at General Dynamics' Electric Boat Division in Groton, Connecticut, by Harry S. Truman on 14 June 1952.[13] She was christened on 21 January 1954 and launched into the Thames River, sponsored by Mamie Eisenhower. Nautilus was commissioned on 30 September 1954, under the command of Commander Eugene P. Wilkinson, USN.[2]

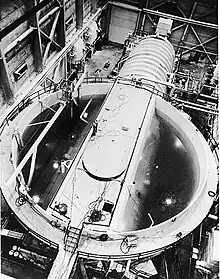

Nautilus was powered by the Submarine Thermal Reactor (STR), later redesignated the S2W reactor, a pressurized water reactor produced for the US Navy by Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Bettis Atomic Power Laboratory, operated by Westinghouse, developed the basic reactor plant design used in Nautilus after being given the assignment on 31 December 1947 to design a nuclear power plant for a submarine.[14] Nuclear power had a crucial advantage in submarine propulsion because it is a zero-emission process that consumes no air. This design is the basis for nearly all of the US nuclear-powered submarine and surface combat ships, and was adapted by other countries for naval nuclear propulsion. The first actual prototype (for Nautilus) was constructed and tested by the Argonne National Laboratory in 1953 at S1W at the Naval Reactors Facility, part of the National Reactor Testing Station in Idaho.[15][16]

Nautilus' ship's patch was designed by The Walt Disney Company, and her wardroom currently displays a set of tableware made of zirconium, as the nuclear fuel cladding was partly made of zirconium.

"Underway on nuclear power"

Following her commissioning, Nautilus remained dockside for further construction and testing. On the morning of 17 January 1955, at 11 am EST, Nautilus' first Commanding Officer, Commander Eugene P. Wilkinson, ordered all lines cast off and signaled the memorable and historic message, "Underway on nuclear power."[17] On 10 May, she headed south for shakedown. Submerged throughout, she traveled 1,100 nmi (2,000 km; 1,300 mi) from New London to San Juan, Puerto Rico and covered 1,200 nmi (2,200 km; 1,400 mi) in less than ninety hours. At the time, this was the longest submerged cruise by a submarine and at the highest sustained speed (for at least one hour) ever recorded.

From 1955 to 1957, Nautilus continued to be used to investigate the effects of increased submerged speeds and endurance. These improvements rendered the progress made in anti-submarine warfare during World War II virtually obsolete. Radar and anti-submarine aircraft, which had proved crucial in defeating submarines during the war, proved ineffective against a vessel able to move quickly out of an area, change depth quickly and stay submerged for very long periods.[18]

On 4 February 1957, Nautilus logged her 60,000th nautical mile (110,000 km; 69,000 mi), matching the endurance of her namesake, the fictional Nautilus described in Jules Verne's novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea.[19] In May, she departed for the Pacific Coast to participate in coastal exercises and the fleet exercise, operation "Home Run," which acquainted units of the Pacific Fleet with the capabilities of nuclear submarines.

Nautilus returned to New London, Connecticut, on 21 July and departed again on 19 August for her first voyage of 1,200 nmi (2,200 km; 1,400 mi) under the polar pack ice. Thereafter, she headed for the Eastern Atlantic to participate in NATO exercises and conduct a tour of various British and French ports where she was inspected by defense personnel of those countries. She arrived back at New London on 28 October, underwent upkeep, and then conducted coastal operations until the spring.

Operation Sunshine – under the North Pole

In response to the nuclear ICBM threat posed by Sputnik, President Eisenhower ordered the U.S. Navy to attempt a submarine transit of the North Pole to gain credibility for the soon-to-come SLBM weapons system.[20] On 25 April 1958, Nautilus was underway again for the West Coast, now commanded by Commander William R. Anderson, USN. Stopping at San Diego, San Francisco, and Seattle, she began her history-making polar transit, "Operation Sunshine", as she departed the latter port on 9 June. On 19 June, she entered the Chukchi Sea, but was turned back by deep drift ice in those shallow waters. On 28 June, she arrived at Pearl Harbor to await better ice conditions.

By 23 July, her wait was over, and she set a course northward.[21] She submerged in the Barrow Sea Valley on 1 August and on 3 August, at 2315 hrs. EDT she became the first watercraft to reach the geographic North Pole.[22] The ability to navigate at extreme latitudes without surfacing was enabled by the technology of the North American Aviation N6A-1 Inertial Navigation System, a naval modification of the N6A used in the Navaho cruise missile; it had been installed on Nautilus and Skate after initial sea trials on USS Compass Island in 1957.[23] From the North Pole, she continued and after 96 hours and 1,590 nmi (2,940 km; 1,830 mi) under the ice, surfaced northeast of Greenland, having completed the first successful submerged voyage around the North Pole. The technical details of this mission were planned by scientists from the Naval Electronics Laboratory including Dr. Waldo Lyon who accompanied Nautilus as chief scientist and ice pilot.[24]

Navigation beneath the arctic ice sheet was difficult. Above 85°N both magnetic compasses and normal gyrocompasses become inaccurate. A special gyrocompass built by Sperry Rand was installed shortly before the journey. There was a risk that the submarine would become disoriented beneath the ice and that the crew would have to play "longitude roulette". Commander Anderson had considered using torpedoes to blow a hole in the ice if the submarine needed to surface.[25]

The most difficult part of the journey was in the Bering Strait. The ice extended as much as 60 ft (18 m) below sea level. During the initial attempt to go through the Bering Strait, there was insufficient room between the ice and the sea bottom. During the second, successful attempt to pass through the Bering passage, the submarine passed through a known channel close to Alaska (this was not the first choice, as the submarine wanted to avoid detection).

The trip beneath the ice cap was an important boost for America as the Soviets had recently launched Sputnik, but had no nuclear submarine of their own. During the address announcing the journey, the president mentioned that one day nuclear cargo submarines might use that route for trade.[26]

As Nautilus proceeded south from Greenland, a helicopter airlifted Commander Anderson to connect with transport to Washington, D.C. At a White House ceremony on 8 August, President Eisenhower presented him with the Legion of Merit and announced that the crew had earned a Presidential Unit Citation.[27]

At her next port of call, the Isle of Portland, England, she received the Unit Citation, the first ever issued in peace time, from American Ambassador JH Whitney, and then crossed the Atlantic reaching New London, Connecticut, on 29 October. For the remainder of the year, Nautilus operated from her home port of New London.

Operational history

Following fleet exercises in early 1959, Nautilus entered the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, for her first complete overhaul (28 May 1959 – 15 August 1960). Overhaul was followed by refresher training and on 24 October she departed New London for her first deployment with the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean Sea, returning to her home-port on 16 December.

Nautilus spent most of her career assigned to Submarine Squadron 10 (SUBRON 10) at State Pier in New London, Connecticut. Nautilus and other submarines in the squadron made their home tied up alongside the tender, where they received preventive maintenance, and if necessary, repairs, from the well-equipped submarine tender USS Fulton (AS-11) and her crew of machinists, millwrights, and other craftsmen.

Nautilus operated in the Atlantic, conducting evaluation tests for ASW improvements, participating in NATO exercises, and during October 1962, in the naval quarantine of Cuba, until she headed east again for a two-month Mediterranean tour in August 1963. On her return she joined in fleet exercises until entering the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard for her second overhaul on 17 January 1964.

On 2 May 1966, Nautilus returned to her homeport to resume operations with the Atlantic Fleet, and at some point during that month, logged her 300,000th nautical mile (560,000 km; 350,000 mi) underway. For the next year and a quarter she conducted special operations for ComSubLant and then in August 1967, returned to Portsmouth, for another year's stay. During an exercise in 1966 she collided with the aircraft carrier USS Essex on 10 November, while at shallow depth.[28] Following repairs in Portsmouth she conducted exercises off the southeastern seaboard. She returned to New London in December 1968 and operated as a unit of Submarine Squadron 10 for most of the remainder of her career.

On 9 April 1979, Nautilus set out from Groton, Connecticut on her final voyage[29] under the command of Richard A. Riddell.[30] She reached Mare Island Naval Shipyard of Vallejo, California on 26 May 1979, her last day underway. She was decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 3 March 1980.[31]

Noise

Toward the end of her service, the hull and sail of Nautilus vibrated sufficiently that sonar became ineffective at more than 4 kn (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph) speed.[32] As noise generation is extremely undesirable in submarines, this made the vessel vulnerable to sonar detection. Lessons learned from this problem were applied to later nuclear submarines.[33]

Awards and commendations

| Presidential Unit Citation with Operation Sunshine clasp |

National Defense Service Medal |

Presidential Unit Citation

For outstanding achievement in completing the first voyage in history across the top of the world, by cruising under the Arctic ice cap from the Bering Strait to the Greenland Sea.

During the period 22 July 1958 to 5 August 1958, USS Nautilus, the world's first nuclear powered ship, added to her list of historic achievements by crossing the Arctic Ocean from the Bering Sea to the Greenland Sea, passing submerged beneath the geographic North Pole. This voyage opens the possibility of a new commercial seaway, a Northwest Passage, between the major oceans of the world. Nuclear-powered cargo submarines may, in the future, use this route to the advantage of world trade.

The skill, professional competency and courage of the officers and crew of Nautilus were in keeping with the highest traditions of the Armed Forces of the United States and the pioneering spirit which has always characterized the country.[34]

To commemorate the first submerged voyage under the North Pole, all Nautilus crewmembers who made the voyage may wear a Presidential Unit Citation ribbon with a special clasp in the form of a gold block letter N (image above).[35]

Museum

Nautilus was designated a National Historic Landmark by the United States Secretary of the Interior on 20 May 1982.[6][36]

She was named as the official state ship of Connecticut in 1983.[37] Following an extensive conversion at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, Nautilus was towed back to Groton, under the command of Captain John Almon, arriving on 6 July 1985. On 11 April 1986, Nautilus opened to the public as part of the Submarine Force Library and Museum.[22]

Nautilus now serves as a museum of submarine history operated by the Naval History and Heritage Command. The ship underwent a five-month preservation in 2002 at Electric Boat, at a cost of approximately $4.7 million (~$7.35 million in 2022). Nautilus attracts some 250,000 visitors annually to her present berth near Naval Submarine Base New London.[38]

Nautilus celebrated the 50th anniversary of her commissioning on 30 September 2004 with a ceremony that included a speech from Vice Admiral Eugene P. Wilkinson, her first Commanding Officer, and a designation of the ship as an American Nuclear Society National Nuclear Landmark.

Visitors may tour the forward two compartments, with guidance from an automated system. Despite similar alterations to exhibit the engineering spaces, tours aft of the control room are not permitted due to safety and security concerns.

In March of 2022, Nautilus began a restoration process that was expected to last 6 to 8 months. Included in the work: blasting and painting of the hull, installation of new top decks, as well as upgraded interior lighting and electrical.[39] The restoration was completed at a cost of US$36 million.[40]

See also

- USS Skate (SSN-578) (first submarine to surface at the North Pole)

- National Register of Historic Places listings in New London County, Connecticut

- List of museum ships

- Submarine Cargo Vessel

- Merchant submarine

References

Notes

- ↑ "Nautilus IV (SSN-571)".

- 1 2 3 "Nautilus IV (SSN-571)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 1970.

- ↑ Polmar, Norman; Moore, Kenneth J. Cold War submarines: the design and construction of US and Soviet submarines. Brassey's.

- ↑ Christley, Jim; Bryan, Tony. US Nuclear Submarines: The Fast Attack. Osprey.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 23 January 2007.

- 1 2 "Nautilus (Nuclear Submarine)". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ↑ Winters, Ann (28 March 2017). "Underway on Nuclear Power" -- The Man Behind the Words: Eugene P. "Dennis" Wilkinson, Vice Admiral USN. The American Nuclear Society.

- ↑ Verne, Jules. 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas. Translated by Frederick Paul Walter – via Wikisource.

- ↑ "Nautilus III (SS-168)". public1.nhhcaws.local. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ↑ Friedman, Submarines, pp 182

- ↑ Hewlett & Duncan, Nuclear Navy, pp. 162

- ↑ "Biography of Admiral Hyman G. Rickover". Naval History & Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Video: Atom Sub. President Officiates At Laying Of Keel, 1952/06/16 (1952). Universal Newsreels. 1952.

- ↑ "Lab's early submarine reactor program paved the way for modern nuclear power plants". Argonne's Nuclear Science and Technology Legacy (Press release). Argonne National Laboratory. 21 January 1996. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "Argonne National Laboratory News Release, 21 January 1996, retrieved 31 December 2014". Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ "Reactors designed by Argonne National Laboratory, retrieved 31 December 2014". Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "USS Nautilus Events". www.ussnautilus.org. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011.

- ↑ Friedman, Submarines, pp 109

- ↑ "Nautilus IV (SSN-571)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

On 4 February 1957, Nautilus logged her 60,000th nautical mile to bring to reality the achievements of her fictitious namesake in Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

- ↑ Anderson, William R. "Fact Sheet – USS Nautilus and Voyage to North Pole, August 1958" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "Submarine Force Museum, History of USS NAUTILUS (SSN 571)". Archived from the original on 19 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- 1 2 "History of USS Nautilus (SSN 571)". Submarine Force Library and Museum. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Steel Boats, Iron Men: History of the US Submarine Force. Turner. 1994. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-56311-081-8. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Leary, William M. (1999). Under Ice: Waldo Lyon and the Development of the Arctic Submarine. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

- ↑ Konstam, Angus (May 2010) [2008]. Naval Miscellany. Oxprey. ISBN 978-1846039898.

- ↑ Anderson, William R; Blair, Clay (May 1989) [1959]. Nautilus 90 North. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-8306-4005-3.

- ↑ "Atomic Sub Crosses North Pole," Richmond Times-Dispatch, Richmond, VA (9 August 1958).

- ↑ "Viewing a thread".

- ↑ "Nautilus (SSN-571)". history.navy.mil. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ↑ "Book Talk with Dick Riddell". thekensingtonfallschurch.com. KENSINGTON SENIOR LIVING. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ↑ "Navy retires Nautilus sub after 25 years". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. 4 March 1980. p. 7B.

- ↑ "Riddell lecture 2004". Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ Norman Polmar and Kenneth J. Moore (14 May 2014). "Chapter 4". Cold War Submarines. The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. Potomac Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1-57488-530-9.

- ↑ "Citation – Presidential Unit Citation for making the first submerged voyage under the North Pole". US Navy Submarine Force Museum. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009.

- ↑ "Navy Presidential Unit Citation". 1st Amphibian Tractor Battalion. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑

Sheire, James W. (12 February 1982). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination / USS Nautilus (SSN-571)" (pdf). National Park Service. Retrieved 6 September 2012. and

"Accompanying Photos". National Park Service. Retrieved 6 September 2012. - ↑ "State of Connecticut, Sites, Seals, Symbols". Connecticut State Register & Manual. Archived from the original on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ↑ "WELCOME TO NAVAL SUBMARINE BASE NEW LONDON". cnrma.cnic.mil. Official U.S. Navy Website. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ↑ "Facelift for a fabled submarine that has sailed into history - the Boston Globe". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ Moser, Erica (10 September 2022). "World's First Nuclear-Powered Submarine Returns Home After a $36 Million Facelift". Military.com. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

Sources

- Friedman, Norman (1994). U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 1-55750-260-9.

- Hewlett, Richard; Duncan, Francis (1974). Nuclear Navy 1946-1962. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32219-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)

External links

- US Navy Submarine Force Museum: Official home of USS Nautilus

- Nautilus Alumni Association : Information for former Nautilus crewmembers

- USS Nautilus (SSN-571) at Historic Naval Ships Association: USS Nautilus

- Documents regarding the USS Nautilus (SSN-571), Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- A film clip A-Sub Epic. Nautilus Pioneers North Pole Seaway, 1958/08/11 (1958)) is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- Reagle, Jason (Summer 2009). "The First ICEX: A Historical Journey of USS Nautilus (SSN-571)". Undersea Warfare. U.S. Navy. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- Photo gallery of USS Nautilus at NavSource.org

- Old NavSource USS Nautilus Photo gallery

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.