Republic of Sierra Leone | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Unity, Freedom, Justice" | |

| Anthem: "High We Exalt Thee, Realm of the Free" | |

.svg.png.webp) Location of Sierra Leone (dark green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Freetown 08°30′00″N 12°06′00″W / 8.50000°N 12.10000°W |

| Official languages | English |

| Recognised national languages | Krio |

| Ethnic groups (2015[1]) | |

| Demonym(s) | Sierra Leonean |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Julius Maada Bio | |

| Mohamed Juldeh Jalloh | |

| David Sengeh | |

| Abass Chernor Bundu | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• Dominion | 27 April 1961 |

• Republic | 19 April 1971 |

| Area | |

• Total | 71,740 km2 (27,700 sq mi) (117th) |

• Water (%) | 1.1 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 8,908,040[2] (100th) |

• Density | 112/km2 (290.1/sq mi) (114tha) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | 35.7[4] medium |

| HDI (2021) | low · 181st |

| Currency | Leone (SLL) |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +232 |

| ISO 3166 code | SL |

| Internet TLD | .sl |

| |

Sierra Leone,[note 1] officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It shares its southeastern border with Liberia, and the northern half of the nation is surrounded by Guinea. Covering a total area of 71,740 km2 (27,699 sq mi),[9] Sierra Leone has a tropical climate, with diverse environments ranging from savanna to rainforests. The country has a population of 7,092,113 as of the 2015 census.[10] Freetown is the capital and largest city. The country is divided into five administrative regions, which are subdivided into 16 districts.[11][12]

Sierra Leone is a presidential republic with a unicameral parliament and a directly elected president. Sierra Leone is a secular state with the constitution providing for the separation of state and religion and freedom of conscience (which includes freedom of thoughts and religion).[13] Muslims make up about three-quarters of the population, though with an influential Christian minority. Religious tolerance in the West African country is very high and is generally considered a norm and part of Sierra Leone's cultural identity.[14]

The geographic area has been inhabited for millennia, but Sierra Leone, as the country and its borders are known today, was founded by the British Crown in two phases: first, the coastal Sierra Leone Colony in 1808 (for returning Africans after the abolition of the slave trade); second, the inland Protectorate in 1896 (as the Crown sought to establish more dominion inland following the outcome of the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885). Hence, the country formally became known as the Sierra Leone Colony and Protectorate or simply British Sierra Leone.[15][16] Sierra Leone gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1961, becoming a Commonwealth realm as the Dominion of Sierra Leone with Sir Milton Margai of the Sierra Leone People's Party (SLPP) as the country's first prime minister.[17]

A new constitution was adopted in 1971, transforming the country into a presidential republic led by Siaka Stevens of the All People's Congress (APC). After declaring the APC the sole legal party in 1978, Stevens was succeeded by Joseph Saidu Momoh in 1985, who enacted a new constitution reintroducing a multi-party system in 1991. A brutal civil war between the government and the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebel group broke out the same year, which went on for 11 years with devastating effects. During the war, the country experienced three coups d'état and alternated between civilian and military rule. Following military interventions by the ECOMOG and later the United Kingdom, the RUF was definitively defeated in 2002. The country has remained relatively stable since then, and is attempting to recover from the war. The two main political parties are the APC and the SLPP.

About 18 ethnic groups inhabit Sierra Leone; the two largest and most influential ones are the Temne and Mende peoples. About 1.2% of the country's population are Creole people, descendants of freed African-American and Afro-Caribbean slaves and liberated Africans. English is the official language used in schools and government administration. Krio is the most widely spoken language across Sierra Leone, spoken by 97% of the country's population. Sierra Leone is rich in natural resources, especially diamond, gold, bauxite and aluminium. The country is a member of the United Nations, African Union, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Mano River Union, Commonwealth of Nations, IMF, World Bank, WTO, African Development Bank, and Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

Etymology

The country takes its name from the Lion Mountains near Freetown. Originally named Serra Leoa (Portuguese for 'lioness mountains') by Portuguese explorer Pedro de Sintra in 1462, the modern name is derived from the Venetian spelling, which was introduced by Venetian explorer Alvise Cadamosto and subsequently copied by other European mapmakers.[18]

History

Early history

Archaeological finds show that Sierra Leone has been inhabited continuously for at least 2,500 years;[20] populated successively by societies who migrated from other parts of Africa.[21] The use of iron was adopted by the ninth century, and by 1000 AD, agriculture was being practised along the coast.[22] Over time, the climate changed considerably, altering boundaries between different ecological zones, affecting migration and conquest.[23]

Sierra Leone's dense tropical rainforest and swampy environment were considered impenetrable; it was also host to the tsetse fly, which carried a disease fatal to horses and the zebu cattle used by the Mande-speaking people. This environment protected its people from conquest by the Mandinka and other African empires,[23][24] and limited the influence of the Mali Empire. Islam was introduced by Susu traders, merchants and migrants from the north and east, becoming widely adopted in the 18th century.After the initial introduction of Islam by the Susu Islam came in various other waves gradually forming a foothold in the northern regions. Later conquest by Samory Touré in the North East resulted islam being cemented amongst the Yalunka,Kuranko and Limba people.[25]

European trading

European contacts within Sierra Leone were among the first in West Africa during the 15th century. In 1462, Portuguese explorer Pedro de Sintra mapped the hills surrounding what is now Freetown Harbour, naming the shaped formation Serra da Leoa or "Serra Leoa" (Portuguese for Lioness Mountains).[26] The Spanish rendering of this geographic formation is Sierra Leona, which later was adapted, misspelled and became the country's current name. Though according to Professor C. Magbaily Fyle, this might have been a misinterpretation by historians. According to Professor Fyle, there has been evidence of travellers calling the region Serra Lyoa long before 1462 (before the first arrival of Sintra to the region). This would imply that the identity of the person who named Sierra Leone is unknown.[27] Soon after Sintra's expedition, Portuguese traders started arriving at the harbour. By 1495, they had built a fortified trading post on the coast.[28]

Traders from European nations, such as the Dutch Republic, England and France also started to arrive in Sierra Leone and establish trading stations. These stations quickly began to primarily deal in slaves, who were brought to the coast by indigenous traders from interior areas undergoing wars and conflicts over territory. The Europeans made payments, called Cole, for rent, tribute, and trading rights, to the king of an area. Local Afro-European merchants often acted as middlemen, the Europeans advancing them goods to trade to indigenous merchants, most often for slaves and ivory.[29][30] Sir Francis Drake reached Sierra Leone on 22 July 1580 as the last stop of his voyage along the west coast of Africa. Bunce Island, an island on the Sierra Leone River, was used as a base by European slavers as a place for slave ships to dock before sailing via the Middle Passage to the Americas. Until the passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807, the island was operated by the London-based firm Grant, Oswald & Company, who occupied it in 1748.[31]

Early Portuguese Interactions

Ivory carving was a notable skill in many parts of west Africa. The costal groups that inhabited what is now Sierra Leone during the 15th century were no different and caught the eye of Portuguese explorers.The Portuguese were impressed with the Ivory carving capabilities of the local coastal people described as Sapes as a result a high demand of Ivory works were commissioned by Portuguese traders. This resulted in an array of Ivory works like Ivory horns, saltcellars and spoons being produced in the region. A notable piece of work was the sapi saltceller.

Manes Expansion

During the 1600s there were multiple waves of Mande speaking groups into the area of what is now Sierra Leone.

Black Poor of London

In the late 18th century, many African Americans claimed the protection of the British Crown. There were thousands of these Black Loyalists, people of African ancestry who joined the British military forces during the American Revolutionary War.[32] Many of these Loyalists had been slaves who had escaped to join the British, lured by promises of freedom (emancipation). The official documentation known as the Book of Negroes lists thousands of freed slaves whom the British evacuated from the nascent United States and resettled in colonies elsewhere in British North America (north to Canada, or south to the West Indies).

Pro-slavery advocates accused the Black Poor of being responsible for a large proportion of crime in 18th century London. While the broader community included some women, the Black Poor seems to have exclusively consisted of men, some of whom developed relationships with local women and often married them. Slave owner Edward Long criticized marriage between black men and white women.[33] However, on the voyage between Plymouth, England and Sierra Leone, seventy European girlfriends and wives accompanied the Black Poor settlers.[34]

Many in London thought that moving them to Sierra Leone would lift them out of poverty.[35] The Sierra Leone Resettlement Scheme was proposed by entomologist Henry Smeathman and drew interest from humanitarians like Granville Sharp, who saw it as a means of showing the pro-slavery lobby that black people could contribute towards the running of the new colony of Sierra Leone. Government officials soon became involved in the scheme as well, although their interest was spurred by the possibility of resettling a large group of poor citizens elsewhere.[36] William Pitt the Younger, prime minister and leader of the Tory party, had an active interest in the Scheme because he saw it as a means to repatriate the Black Poor to Africa, since "it was necessary they should be sent somewhere, and be no longer suffered to infest the streets of London".[33]

Province of Freedom

In January 1787, the Atlantic and the Belisarius set sail for Sierra Leone, but bad weather forced them to divert to Plymouth, during which time about 50 passengers died. Another 24 were discharged, and another 23 ran away. Eventually, with some more recruitment, 411 passengers sailed to Sierra Leone in April 1787. On the voyage between Plymouth and Sierra Leone, 96 passengers died.[33][37][38][39]

In 1787 the British Crown founded a settlement in Sierra Leone in what was called the "Province of Freedom". About 400 black and 60 white colonists reached Sierra Leone on 15 May 1787. After they established Granville Town, most of the first group of colonists died, owing to disease and warfare with the indigenous African peoples (Temne), who resisted their encroachment. When the ships left them in September, their numbers had been reduced to "276 persons, namely 212 black men, 30 black women, 5 white men and 29 white women".[33]

The settlers that remained forcibly captured land from a local African chieftain, but he retaliated, attacking the settlement, which was reduced to a mere 64 settlers comprising 39 black men, 19 black women, and six white women. Black settlers were captured by unscrupulous traders and sold as slaves, and the remaining colonists were forced to arm themselves for their own protection.[33] The 64 remaining colonists established a second Granville Town.[40][41]

Nova Scotians

Following the American Revolution, more than 3,000 Black Loyalists had also been settled in Nova Scotia, where they were finally granted land. They founded Birchtown, but faced harsh northern winters and racial discrimination from nearby Shelburne. Thomas Peters pressed British authorities for relief and more aid; together with British abolitionist John Clarkson, the Sierra Leone Company was established to relocate Black Loyalists who wanted to take their chances in West Africa. In 1792 nearly 1,200 persons from Nova Scotia crossed the Atlantic to build the second (and only permanent) Colony of Sierra Leone and the settlement of Freetown on 11 March 1792. In Sierra Leone they were called the Nova Scotian Settlers, the Nova Scotians, or the Settlers. Clarkson initially banned the survivors of Granville Town from joining the new settlement, blaming them for the demise of Granville Town.[33] The Settlers built Freetown in the styles they knew from their lives in the American South; they also continued American fashion and American manners. In addition, many continued to practise Methodism in Freetown.

In the 1790s, the Settlers, including adult women, voted for the first time in elections.[42] In 1792, in a move that foreshadowed the women's suffrage movements in Britain, the heads of all households, of which a third were women, were given the right to vote.[43] Black settlers in Sierra Leone enjoyed much more autonomy than their white equivalent in European countries. Black migrants elected different levels of political representatives, 'tithingmen', who represented each dozen settlers and 'hundreders' who represented larger amounts. This sort of representation was not available in Nova Scotia.[44] The initial process of society-building in Freetown was a harsh struggle. The Crown did not supply enough basic supplies and provisions and the Settlers were continually threatened by illegal slave trading and the risk of re-enslavement.[45]

Jamaican Maroons and Liberated Africans

The Sierra Leone Company, controlled by London investors, refused to allow the settlers to take freehold of the land. In 1799 some of the settlers revolted. The Crown subdued the revolt by bringing in forces of more than 500 Jamaican Maroons, whom they transported from Cudjoe's Town (Trelawny Town) via Nova Scotia in 1800. Led by Colonel Montague James, the Maroons helped the colonial forces to put down the revolt, and in the process the Jamaican Maroons in Sierra Leone secured the best houses and farms.[46]

On 1 January 1808, Thomas Ludlam, the Governor of the Sierra Leone Company and a leading abolitionist, surrendered the company's charter. This ended its 16 years of running the Colony. The British Crown reorganised the Sierra Leone Company as the African Institution; it was directed to improve the local economy. Its members represented both British who hoped to inspire local entrepreneurs and those with interest in the Macauley & Babington Company, which held the (British) monopoly on Sierra Leone trade.[47]

At about the same time (following the Slave Trade Act 1807 which abolished the slave trade), Royal Navy crews delivered thousands of formerly enslaved Africans to Freetown, after liberating them from illegal slave ships. These Liberated Africans or recaptives were sold for $20 a head as apprentices to the white settlers, Nova Scotian Settlers, and the Jamaican Maroons. Many Liberated Africans were treated poorly and even abused because some of the original settlers considered them their property. Cut off from their various homelands and traditions, the Liberated Africans were forced to assimilate to the Western styles of Settlers and Maroons. For example, some of the Liberated Africans were forced to change their name to a more Western sounding one.[48] Though some people happily embraced these changes because they considered it as being part of the community, some were not happy with these changes and wanted to keep their own identity. Many Liberated Africans were so unhappy that they risked the possibility of being sold back into slavery by leaving Sierra Leone and going back to their original villages.[48] The Liberated Africans eventually modified their customs to adopt those of the Nova Scotians, Maroons and Europeans, yet kept some of their ethnic traditions.[49] As the Liberated Africans became successful traders[48] and spread Christianity throughout West Africa, they intermarried with the Nova Scotians and Maroons, and the two groups eventually became a fusion of African and Western societies.[49]: 3–4, 223–255

These Liberated Africans were from many areas of Africa, but principally the west coast. Between the 18th and 19th century, freed African Americans, some Americo Liberian "refugees", and particularly Afro-Caribbeans, mainly Jamaican Maroons, also immigrated and settled in Freetown. Together these peoples formed the Creole/Krio ethnicity and an English-based creole language, (Krio), which is the lingua franca and de facto national language used among many of the ethnicities in the country.[50][51][52][53]

Colonial era (1800–1961)

The settlement of Sierra Leone in the 1800s was unique in that the population was composed of displaced Africans who were brought to the colony after the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Upon arrival in Sierra Leone, each recaptive was given a registration number, and information on their physical qualities would be entered into the Register of Liberated Africans. Oftentimes the documentation would be overwhelmingly subjective and would result in inaccurate entries, making them difficult to track. In addition, differences between the Register of Liberated Africans of 1808 and the List of Captured Negroes of 1812 (which emulated the 1808 document) revealed some disparities in the entries of the recaptives, specifically in the names; many recaptives decided to change their given names to more anglicised versions which contributed to the difficulty in tracking them after they arrived in Sierra Leone.[54]

In the early 19th century, Freetown served as the residence of the British colonial governor of the region, who also administered the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and the Gambia settlements. Sierra Leone developed as the educational centre of British West Africa.[55] The British established Fourah Bay College in 1827, which rapidly became a magnet for English-speaking Africans on the West Coast. For more than a century, it was the only European-style university in western Sub-Saharan Africa. Samuel Ajayi Crowther was the first student to be enrolled at Fourah Bay.[56] Fourah Bay College soon became a magnet for Creoles/Krio people and other Africans seeking higher education in British West Africa. These included Nigerians, Ghanaians, Ivorians and many more, especially in the fields of theology and education. Freetown was known as the "Athens of Africa" due to the large number of excellent schools in Freetown and surrounding areas.[57]

The British interacted mostly with the Krio people in Freetown, who did most of the trading with the indigenous peoples of the interior. Educated Krio people held numerous positions in the colonial government, giving them status and well-paying positions. Following the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, the British decided that they needed to establish more dominion over the inland areas, to satisfy what was described by the European powers as "effective occupation" of territories. In 1896 it annexed these areas, declaring them the Sierra Leone Protectorate.[58] With this change, the British began to expand their administration in the region, recruiting British citizens to posts and pushing Krio people out of positions in government and even the desirable residential areas in Freetown.[58]

During the British annexation in Sierra Leone, several chiefs in the northern and southern parts of the country were resisting the "hut tax" imposed by the colonial administrators but they used diplomacy to achieve their goal. In the north, from 1820 to 1906, there was a Limba chief named Almamy Suluku who ruled his territory for many years, fighting to protect his territory, while at the same time using diplomacy to trick the protectorate administrators while sending fighters to assist Bai Bureh, a prominent Temne chief in Kasseh who was fighting against the imposition of the "hut tax" by the colonial administrators. The war was later known as the Hut Tax War. Another prominent figure in Sierra Leone history is Bai Sherbro (c. 1830–1912). Bai Sherbro was a chief and warrior on Bonthe Island, in the southwestern part of the country. He, like Bai Bureh, resisted the British. Sherbro also sent fighters to assist Bai Bureh in the fight against the British. Sherbro was influential and powerful and the British greatly feared him. Bai Sherbro was captured and with Bai Bureh, exiled to the Gold Coast (modern Ghana).

Nyagua (c. 1842–1906), also known as the "Tracking King", was a fierce king who captured many districts and many people came to join him for protection. Nyagua also resisted the British. Realizing that he lacked sufficient strength, he resorted to diplomacy. At the same time, he sent warriors to assist Bai Bureh in fighting against the British. The British later captured Nyagua, and he was also exiled to the Gold Coast. Madam Yoko (c. 1849–1906) was a brilliant woman of culture and ambition. She employed her capacity for friendly communications to persuade the British to give her control of the Kpaa Mende chiefdom. She used diplomacy to communicate with many local chiefs who did not trust her friendship with the British. Because Madam Yoko supported the British, some sub-chiefs rebelled, causing Yoko to take refuge in the police barracks. For her loyalty, she was awarded a silver medal by Queen Victoria. Until 1906, Madam Yoko ruled as a paramount chief in the new British Protectorate. It appears that she committed suicide at the age of fifty-five, perhaps due to the loss of support from her own people.

The British annexation of the Protectorate interfered with the sovereignty of indigenous chiefs. They designated chiefs as units of local government, rather than dealing with them individually as had been the previous practice. They did not maintain relationships even with longstanding allies, such as Bai Bureh, who was later unfairly portrayed as a prime instigator of the Hut Tax War.[59]

Colonel Frederic Cardew, military governor of the Protectorate, in 1898 established a new tax on dwellings and demanded that the chiefs use their people to maintain roads. The taxes were often higher than the value of the dwellings, and 24 chiefs signed a petition to Cardew, stating how destructive this was; their people could not afford to take time off from their subsistence agriculture. They resisted payment of taxes, tensions over the new colonial requirements and the administration's suspicions towards the chiefs, led to the Hut Tax war of 1898, also called the Temne-Mende War. The British fired first; the northern front of mainly Temne people was led by Bai Bureh. The southern front, consisting mostly of Mende people, entered the conflict somewhat later, for other reasons.

.jpg.webp)

For several months, Bureh's fighters had the advantage over the vastly more powerful British forces but both sides suffered hundreds of fatalities.[60] Bureh surrendered on 11 November 1898 to end the destruction of his people's territory and dwellings. Although the British government recommended leniency, Cardew insisted on sending the chief and two allies into exile in the Gold Coast; his government hanged 96 of the chief's warriors. Bureh was allowed to return in 1905, when he resumed his chieftaincy of Kasseh.[59] The defeat of the Temne and Mende in the Hut Tax war ended mass resistance to the Protectorate and colonial government, but intermittent rioting and labour unrest continued throughout the colonial period. Riots in 1955 and 1956 involved "tens of thousands" of Sierra Leoneans in the Protectorate.[61]

Domestic slavery, which continued to be practised by local African elites, was abolished in 1928.[62] A notable event in 1935 was the granting of a monopoly on mineral mining to the Sierra Leone Selection Trust, run by De Beers. The monopoly was scheduled to last 98 years. Mining of diamonds in the east and other minerals expanded, drawing labourers there from other parts of the country.

In 1924, the UK government divided the administration of Sierra Leone into Colony and Protectorate, with different political systems constitutionally defined for each. The Colony was Freetown and its coastal area; the Protectorate was defined as the hinterland areas dominated by local chiefs. Antagonism between the two entities escalated to a heated debate in 1947, when proposals were introduced to provide for a single political system for both the Colony and the Protectorate. Most of the proposals came from leaders of the Protectorate, whose population far outnumbered that in the colony. The Krios, led by Isaac Wallace-Johnson, opposed the proposals, as they would have resulted in reducing the political power of the Krios in the Colony.

In 1951, Lamina Sankoh (born: Etheldred Jones) collaborated with educated protectorate leaders from different groups, including Sir Milton Margai, Siaka Stevens, Mohamed Sanusi Mustapha, John Karefa-Smart, Kande Bureh, Sir Albert Margai, Amadu Wurie and Sir Banja Tejan-Sie joined together with the powerful paramount chiefs in the protectorate to form the Sierra Leone People's Party or SLPP as the party of the Protectorate. The SLPP leadership, led by Sir Milton Margai, negotiated with the British and the educated Krio-dominated colony based in Freetown to achieve independence.[63] Owing to the astute politics of Milton Margai, the educated Protectorate elites were able to join forces with the paramount chiefs in the face of Krio intransigence. Later, Margai used the same skills to win over opposition leaders and moderate Krio elements to achieve independence from the UK.[64]

In November 1951, Margai oversaw the drafting of a new constitution, which united the separate Colonial and Protectorate legislatures and provided a framework for decolonisation.[65] In 1953, Sierra Leone was granted local ministerial powers and Margai was elected Chief Minister of Sierra Leone.[65] The new constitution ensured Sierra Leone had a parliamentary system within the Commonwealth of Nations.[65] In May 1957, Sierra Leone held its first parliamentary election. The SLPP, which was then the most popular political party in the colony of Sierra Leone as well as being supported by the powerful paramount chiefs in the provinces, won the most seats in Parliament and Margai was re-elected as Chief Minister by a landslide.

1960 Independence Conference

On 20 April 1960, Milton Margai led a 24-member Sierra Leonean delegation at constitutional conferences that were held with the Government of Queen Elizabeth II and British Colonial Secretary Iain Macleod in negotiations for independence held in London.[66][67]

On the conclusion of talks in London on 4 May 1960, the United Kingdom agreed to grant Sierra Leone independence on 27 April 1961.[66][67]

Independence (1961) and Margai Administration (1961–1964)

On 27 April 1961, Sir Milton Margai led Sierra Leone to independence from Great Britain and became the country's first Prime Minister. Sierra Leone had its own parliament and its own prime minister, and had the ability to make 100% of its own laws, however, as with countries such as Canada and Australia, Sierra Leone remained a "Dominion" and Queen Elizabeth was Queen of the independent Dominion of Sierra Leone.[68][69] Thousands of Sierra Leoneans took to the streets in celebration. The Dominion of Sierra Leone retained a parliamentary system of government and was a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The leader of the main opposition All People's Congress (APC), Siaka Stevens, along with Isaac Wallace-Johnson, another outspoken critic of the SLPP government, were arrested and placed under house arrest in Freetown, along with sixteen others charged with disrupting the independence celebration.[70]

In May 1962, Sierra Leone held its first general election as an independent nation. The Sierra Leone People's Party (SLPP) won a plurality of seats in parliament, and Milton Margai was re-elected as prime minister.

Margai was popular among Sierra Leoneans during his time in power, mostly known for his self-effacement. He was neither corrupt nor did he make a lavish display of his power or status.[71] He based the government on the rule of law and the separation of powers, with multiparty political institutions and fairly viable representative structures. Margai used his conservative ideology to lead Sierra Leone without much strife. He appointed government officials to represent various ethnic groups. Margai employed a brokerage style of politics, by sharing political power among political parties and interest groups; especially the involvement of powerful paramount chiefs in the provinces, most of whom were key allies of his government.

After the death of Milton Margai and Albert Margai's tenure (1964–1967)

Upon Milton Margai's unexpected death in 1964, his younger half-brother, Sir Albert Margai, was appointed as Prime Minister by parliament. Sir Albert's leadership was briefly challenged by Foreign Minister John Karefa-Smart, who questioned Sir Albert's succession to the SLPP leadership position. Karefa-Smart led a prominent small minority faction within the SLPP party in opposition of Albert Margai as Prime Minister. However, Karefa-Smart failed to receive broad support within the SLPP in his attempt to oust Albert Margai as both the leader of the SLPP and Prime Minister. The large majority of SLPP members backed Albert Margai over Karefa-Smart. Soon after Albert Margai was sworn in as Prime Minister, he fired several senior government officials who had served in his elder brother Sir Milton's government, viewing them as a threat to his administration, including Karefa-Smart.

Sir Albert resorted to increasingly authoritarian actions in response to protests and enacted several laws against the opposition All People's Congress, whilst attempting to establish a one-party state.[66][67] Sir Albert was opposed to the colonial legacy of allowing executive powers to the Paramount Chiefs, many of whom had been key allies of his late brother Sir Milton. Accordingly, they began to consider Sir Albert a threat to the ruling houses across the country. Margai appointed many non-Creoles to the country's civil service in Freetown, in an overall diversification of the civil service in the capital, which had been dominated by members of the Creole ethnic group. As a result, Albert Margai became unpopular in the Creole community, many of whom had supported Sir Milton. Margai sought to make the army homogeneously Mende,[72] his own ethnic group, and was accused of favouring members of the Mende for prominent positions.

In 1967, riots broke out in Freetown against Margai's policies; in response, he declared a state of emergency across the country. Sir Albert was accused of corruption and of a policy of affirmative action in favour of the Mende ethnic group.[73] He also endeavoured to change Sierra Leone from a democracy to a one-party state.[74] Although possessing the full backing of the country's security forces, he called for free and fair elections.

1967 General Election and military coups (1967–1968)

The APC, with its leader Siaka Stevens, narrowly won a small majority of seats in Parliament over the SLPP in a closely contested 1967 general election. Stevens was sworn in as Prime Minister on 21 March 1967.

Within hours after taking office, Stevens was ousted in a bloodless military coup led by Brigadier General David Lansana, the commander of the Sierra Leone Armed Forces. He was a close ally of Albert Margai, who had appointed him to the position in 1964. Lansana placed Stevens under house arrest in Freetown and insisted that the determination of the Prime Minister should await the election of the tribal representatives to the House. Steven was later freed and fled the country; going into exile in neighbouring Guinea. However, on 23 March 1967, a group of military officers in the Sierra Leone Army led by Brigadier General Andrew Juxon-Smith, staged a counter-coup against Commander Lansana. They seized control of the government, arrested Lansana, and suspended the constitution. The group set up the National Reformation Council (NRC), with Andrew Juxon-Smith as its chairman and Head of State of the country.[75]

On 18 April 1968 a group of low-ranking soldiers in the Sierra Leone Army who called themselves the Anti-Corruption Revolutionary Movement (ACRM), led by Brigadier General John Amadu Bangura, overthrew the NRC junta. The ACRM junta arrested many senior NRC members. They reinstated the constitution and returned power to Stevens, who at last assumed the office of Prime Minister.[76]

Stevens had Bangura arrested in 1970 and charged with conspiracy and treason. He was found guilty and sentenced to death, despite the fact that it was Bangura whose actions led to Stevens' return to power.[77] Brigadier Lansana and Hinga Norman, the main army officers involved in the first coup (1967), were unceremoniously dismissed from the armed forces and made to serve time in prison. Norman was a guard to Governor-general Sir Henry Lightfoot-Boston.[17] Lansana was later tried and found guilty of treason and sentenced to death in 1975.[17]

One-party state and dawn of the 'Republic' (1968–1991)

Stevens assumed power as Prime Minister again in 1968, following a series of coups, with a great deal of hope and ambition.[17] Much trust was placed upon him as he championed multi-party politics. Stevens had campaigned on a platform of bringing the tribes together under socialist principles. During his first decade or so in power, Stevens renegotiated some of what he called "useless prefinanced schemes" contracted by his predecessors, both Albert Margai of the SLPP and Juxon-Smith of the NRC. Some of these policies by the SLPP and the NRC were said to have left the country in an economically deprived state.[17]

Stevens reorganised the country's oil refinery, the government-owned Cape Sierra Hotel, and a cement factory.[78] He cancelled Juxon-Smith's construction of a church and mosque on the grounds of Victoria Park (now known as Freetown Amusement Park – since 2017). Stevens began efforts that would later improve transportation and movements between the provinces and the city of Freetown. Roads and hospitals were constructed in the provinces, and Paramount Chiefs and provincial peoples became a prominent force in Freetown.

Under the pressure of several coup attempts, real or perceived, Stevens' rule grew more and more authoritarian, and his relationship with some of his ardent supporters deteriorated. He removed the SLPP party from competitive politics in general elections, some believed, through the use of violence and intimidation. To maintain the support of the military, Stevens retained the popular John Amadu Bangura as head of the Sierra Leone Armed Forces.

After the return to civilian rule, by-elections were held (beginning in autumn 1968) and an all-APC cabinet was appointed. Calm was not completely restored. In November 1968, unrest in the provinces led Stevens to declare a state of emergency across the country. Many senior officers in the Sierra Leone Army were greatly disappointed with Stevens' policies and his handling of the Sierra Leone Military, but none could confront Stevens. Brigadier General Bangura, who had reinstated Stevens as Prime Minister, was widely considered the only person who could control Stevens. The army was devoted to Bangura, and this made him potentially dangerous to Stevens. In January 1970, Bangura was arrested and charged with conspiracy and plotting to commit a coup against the Stevens government. After a trial that lasted a few months, Bangura was convicted and sentenced to death. On 29 March 1970, Brigadier Bangura was executed by hanging in Freetown.

After the execution of Bangura, a group of soldiers loyal to the executed general held a mutiny in Freetown and other parts of the country in opposition to Stevens' government. Dozens of soldiers were arrested and convicted by a court martial in Freetown for their participation in the mutiny against the president. Among the soldiers arrested was a little-known army corporal, Foday Sankoh, a strong Bangura supporter, who would later form the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). Corporal Sankoh was convicted and jailed for seven years at the Pademba Road Prison in Freetown.

In April 1971, a new republican constitution was adopted under which Stevens became president. In the 1972 by-elections, the opposition SLPP complained of intimidation and procedural obstruction by the APC and militia. These problems became so severe that the SLPP boycotted the 1973 general election; as a result, the APC won 84 of the 85 elected seats.[79]

An alleged plot to overthrow President Stevens failed in 1974 and its leaders were executed. In mid-1974, Guinean soldiers, as requested by Stevens, were stationed in the country to help maintain his hold on power, as Stevens was a close ally of then-Guinean president Ahmed Sékou Touré. In March 1976, Stevens was elected without opposition for a second five-year term as president. On 19 July 1975, 14 senior army and government officials, including David Lansana, former cabinet minister Mohamed Sorie Forna (father of writer Aminatta Forna), Brigadier General Ibrahim Bash Taqi and Lieutenant Habib Lansana Kamara were executed after being convicted of attempting a coup to topple president Stevens' government.

In 1977, a nationwide student demonstration against the government disrupted Sierra Leone's politics. The demonstration was quickly put down by the army and Stevens' own personal Special Security Division (SSD), a heavily armed paramilitary force he had created to protect him and maintain his hold on power.[80] SSD officers were loyal to Stevens and were deployed across the country to clamp down on any rebellion or protest against Stevens' government. A general election was called later that year in which corruption was again endemic; the APC won 74 seats and the SLPP 15. In 1978, the APC-dominant parliament approved a new constitution making the country a one-party state. The 1978 constitution made the APC the only legal political party in Sierra Leone.[81] This move led to another major demonstration against the government in many parts of the country, but it was also put down by the army and Stevens' SSD force.

Stevens is generally criticised for dictatorial methods and government corruption, but on a positive note, he kept the country stable and from collapsing into civil war. He created several government institutions that are still in use today. Stevens also reduced ethnic polarisation in government by incorporating members of various ethnic groups into his all-dominant APC government.

Siaka Stevens retired from politics in November 1985 after being in power for eighteen years. The APC named a new presidential candidate to succeed Stevens at the party's last delegate conference, held in Freetown in November 1985. The candidate was Major General Joseph Saidu Momoh, head of the Sierra Leone Armed Forces and Stevens' own choice to succeed him. As head of the armed forces, General Momoh had been loyal to Stevens, who had appointed him to the position. Like Stevens, Momoh was also a member of the minority Limba ethnic group.

As the sole candidate, Momoh was elected president without opposition and sworn in as Sierra Leone's second president on 28 November 1985 in Freetown. A one-party parliamentary election between APC members was held in May 1986. President Momoh appointed his former military colleague and key ally, Major General Mohamed Tarawalie to succeed him as the head of the Sierra Leone Military. General Tarawalie was also a strong loyalist and key Momoh supporter. President Momoh named James Bambay Kamara as the head of the Sierra Leone Police. Bambay Kamara was also a strong Momoh loyalist and supporter. Momoh broke from former President Siaka Stevens by integrating the powerful SSD into the Sierra Leone Police as a special paramilitary force. Under President Stevens, the SSD had been a powerful personal force used to maintain his hold on power, independent from the Sierra Leone Military and Sierra Leone Police Force. The Sierra Leone Police under Bambay Kamara's leadership was accused of physical violence, arrest, and intimidation against critics of President Momoh's government.

President Momoh's strong links with the army and his verbal attacks on corruption earned him much-needed initial support among Sierra Leoneans. With the lack of new faces in the new APC cabinet under President Momoh and the return of many of the old faces from Stevens' government, criticisms soon arose that Momoh was simply perpetuating the rule of Stevens.

The next few years under the Momoh administration were characterised by corruption, which Momoh defused by sacking several senior cabinet ministers. To formalise his war against corruption, President Momoh announced a "Code of Conduct for Political Leaders and Public Servants". After an alleged attempt to overthrow President Momoh in March 1987, more than 60 senior government officials were arrested, including Vice-President Francis Minah, who was removed from office, convicted of plotting the coup, and executed by hanging in 1989, along with five others.

Sierra Leone Civil War (1991–2002) and the NPRC regime (1992–1996)

In October 1990, owing to mounting pressure from both within and outside the country for political and economic reforms, president Momoh set up a constitutional review commission to assess the 1978 one-party constitution. Based on the commission's recommendations, a constitution re-establishing a multi-party system was approved by the exclusive APC Parliament by a 60% majority vote, becoming effective on 1 October 1991. There was great suspicion that President Momoh was not serious about his promise of political reform, as APC rule continued to be increasingly marked by abuses of power.

The brutal civil war that was going on in neighbouring Liberia played a significant role in the outbreak of fighting in Sierra Leone. Charles Taylor – then leader of the National Patriotic Front of Liberia – reportedly helped form the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) under the command of former Sierra Leonean army corporal Foday Saybana Sankoh, an ethnic Temne from Tonkolili District in Northern Sierra Leone. Sankoh was a British trained former army corporal who had also undergone guerrilla training in Libya. Taylor's aim was for the RUF to attack the bases of Nigerian dominated peacekeeping troops in Sierra Leone who were opposed to his rebel movement in Liberia.

On 29 April 1992, a group of young soldiers in the Sierra Leone Army, led by seven army officers—Lieutenant Sahr Sandy, Captain Valentine Strasser, Lieutenant Solomon "SAJ" Musa, Captain Komba Mondeh, Lieutenant Tom Nyuma, Captain Julius Maada Bio and Captain Komba Kambo[83]—staged a military coup that sent president Momoh into exile in Guinea, and the young soldiers established the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC), with 25-year-old Captain Valentine Strasser as its chairman and Head of State of the country.[84] The NPRC junta immediately suspended the constitution, banned all political parties, limited freedom of speech and freedom of the press and enacted a rule-by-decree policy, in which soldiers were granted unlimited powers of administrative detention without charge or trial, and challenges against such detentions in court were precluded.

SAJ Musa, a childhood friend of Strasser, became the deputy chairman and deputy leader of the NPRC government. Strasser became the world's youngest Head of State when he seized power just three days after his 25th birthday. The NPRC junta established the National Supreme Council of State as the military highest command and final authority in all matters and was exclusively made up of the highest-ranking NPRC soldiers, including Strasser himself and the original soldiers who toppled President Momoh.[84]

One of the top-ranking soldiers in the NPRC junta, Lieutenant Sahr Sandy, a trusted ally of Strasser, was assassinated, allegedly by Major S.I.M. Turay, a key loyalist of ousted president Momoh. A heavily armed military manhunt was carried out across the country to find Lieutenant Sandy's killer. However, the main suspect, Major S.I.M. Turay, went into hiding and fled the country to Guinea, fearing for his life. Dozens of soldiers loyal to the ousted president Momoh were arrested, including Colonel Kahota M. Dumbuya and Major Yayah Turay. Lieutenant Sandy was given a state funeral and his funeral prayers service at the cathedral church in Freetown was attended by many high-ranking soldiers of the NPRC junta, including Strasser himself and NPRC deputy leader Sergeant Solomon Musa.

The NPRC junta maintained relations with ECOWAS and strengthened support for Sierra Leone-based ECOMOG troops fighting in the Liberian war. On 28 December 1992, an alleged coup attempt against the NPRC government of Strasser, aimed at freeing the detained Colonel Yahya Kanu, Colonel Kahota M.S. Dumbuya and former inspector general of police Bambay Kamara, was foiled. Several Junior army officers led by Sergeant Mohamed Lamin Bangura were identified as being behind the coup plot. The coup plot led to the execution of seventeen soldiers by firing squad. Some of those executed include Colonel Kahota Dumbuya, Major Yayah Kanu and Sergeant Mohamed Lamin Bangura. Several prominent members of the Momoh government who had been in detention at the Pa Demba Road prison, including former inspector general of police Bambay Kamara, were also executed.[85]

On 5 July 1994 SAJ Musa, who was popular among the general population, particularly in Freetown, was arrested and sent into exile after he was accused of planning a coup to topple Strasser, an accusation SAJ Musa denied. Strasser replaced Musa as deputy NPRC chairman with Captain Bio, who was instantly promoted by Strasser to brigadier.

The NPRC's efforts proved to be nearly as ineffective as the ousted Momoh administration in repelling the RUF rebels. More and more of the country fell into the hands RUF fighters, and by 1994 they had gotten control of much of the diamond-rich Eastern Province and were getting close to the capital Freetown. In response, the NPRC hired the services of South African-based private military contractor Executive Outcomes for several hundred mercenary fighters in order to strengthen the response to the advances of the RUF rebels. Within a month they had driven RUF fighters back to enclaves along Sierra Leone's borders and cleared the RUF from the Kono diamond-producing areas of Sierra Leone.

With Strasser's two most senior NPRC allies and commanders Lieutenant Sahr Sandy and Lieutenant Solomon Musa no longer around to defend him, Strasser's leadership within the NPRC's Supreme Council of State became fragile. On 16 January 1996, after about four years in power, Strasser was arrested in a palace coup staged by his fellow NPRC soldiers led by Brigadier Bio at the Defence Headquarters in Freetown.[86] Strasser was immediately flown into exile in a military helicopter to Conakry, Guinea. In his first public broadcast to the nation following the 1996 coup, Brigadier Bio stated that his support for returning Sierra Leone to a democratically elected civilian government and his commitment to ending the civil war were his motivations for the coup.[87]

Kabbah's tenure: government, "dawn of a new republic", the AFRC and end of the Civil War (1996–2007)

Promises of a return to civilian rule were fulfilled by Bio. Prior to conducting the election, Sierra Leoneans and international stakeholders were involved in a major debate on whether the nation should focus on trying to end the long running civil war, or to conduct elections and hence returning governance back to a civilian-led administration with a multi-party system of parliament that would provide the foundation for long-lasting peace and national prosperity. Following the 1995 National Consultative Conference at the Bintumani Hotel in Freetown, dubbed "Bintumani I", which was a Strasser-led initiative, another National Consultative Conference at the same Bintumani Hotel in Freetown, dubbed "Bintumani II", was initiated by the Bio administration that involved both national and international stakeholders, in an effort to find a viable solution to the issues plaguing the country.[88] "Peace before Elections vs Elections before Peace" became a key debate topic and this quickly became a point of national discussion. The discussions eventually concluded with key stakeholders, including Bio's administration and the UN, agreeing that while efforts in finding a peaceful solution to ending the war should continue, a general election should be held as soon as possible.[88] Bio handed power over to Ahmad Tejan Kabbah of the SLPP, after the conclusion of elections in early 1996 which Kabbah won. President Kabbah took power with a great promise of ending the civil war. After taking over, President Kabbah immediately opened dialogue with the RUF and invited their leader Foday Sankoh for peace negotiations.[89]

On 25 May 1997, 17 soldiers in the Sierra Leone army led by Corporal Tamba Gborie, loyal to the detained Major Johnny Paul Koroma, launched a military coup which sent President Kabbah into exile in Guinea and they established the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC). Corporal Gborie quickly went to the Sierra Leone Broadcasting Services headquarters in New England, Freetown to announce the coup to a shocked nation and to alert all soldiers across the country to report for guard duty. The soldiers immediately released Koroma from prison and installed him as their chairman and Head of State.

Koroma suspended the constitution, banned demonstrations, shut down all private radio stations in the country and invited the RUF to join the new junta government, with its leader Foday Sankoh as the Vice-Chairman of the new AFRC-RUF coalition junta government. Within days, Freetown was overwhelmed by the presence of the RUF combatants who came to the city in thousands. The Kamajors, a group of traditional fighters mostly from the Mende ethnic group under the command of deputy Defence Minister Samuel Hinga Norman, remained loyal to President Kabbah and defended the Southern part of Sierra Leone from the soldiers.

After nine months in office, the junta was overthrown by the Nigerian-led ECOMOG forces, and the democratically elected government of president Kabbah was reinstated in February 1998. On 19 October 1998, 24 soldiers in the Sierra Leone army—including Gborie, Brigadier Hassan Karim Conteh, Colonel Samuel Francis Koroma, Major Kula Samba and Colonel Abdul Karim Sesay—were executed by firing squad after they were convicted in a court martial in Freetown, some for orchestrating the 1997 coup that overthrew President Kabbah and others for failure to reverse the mutiny.[90]

In October 1999, the United Nations agreed to send peacekeepers to help restore order and disarm the rebels. The first of the 6,000-member force began arriving in December, and the UN Security Council voted in February 2000 to increase the force to 11,000, and later to 13,000. But in May, when nearly all Nigerian forces had left and UN forces were trying to disarm the RUF in eastern Sierra Leone, Sankoh's forces clashed with the UN troops, and some 500 peacekeepers were taken hostage as the peace accord effectively collapsed. The hostage crisis resulted in more fighting between the RUF and the government as UN troops launched Operation Khukri to end the siege. The Operation was successful with Indian and British Special Forces being the main contingents.

The situation in the country deteriorated to such an extent that British troops were deployed in Operation Palliser, originally simply to evacuate foreign nationals. However, the British exceeded their original mandate and took full military action to finally defeat the rebels and restore order. The British were the catalyst for the ceasefire that ended the civil war. Elements of the British Army, together with administrators and politicians, remained after withdrawal to help train the armed forces, improve the infrastructure of the country and administer financial and material aid. Tony Blair, the Prime Minister of Britain at the time of the British intervention, is regarded as a hero by the people of Sierra Leone, many of whom are keen for more British involvement.[91]

Between 1991 and 2001, about 50,000 people were killed in Sierra Leone's civil war. Hundreds of thousands of people were forced from their homes and many became refugees in Guinea and Liberia. In 2001, UN forces moved into rebel-held areas and began to disarm rebel soldiers. By January 2002, the war was declared over. In May 2002, Kabbah was re-elected president by a landslide. By 2004, the disarmament process was complete. Also in 2004, a UN-backed war crimes court began holding trials of senior leaders from both sides of the war. In December 2005, UN peacekeeping forces pulled out of Sierra Leone.

2007 General Election and the re-emergence of APC

In August 2007, Sierra Leone held presidential and parliamentary elections. However, no presidential candidate won the 50% plus one vote majority stipulated in the constitution on the first round of voting. A runoff election was held in September 2007, and Ernest Bai Koroma, the candidate of the main opposition APC, was elected president. Koroma was re-elected president for a second (and final) term in November 2012.

Struggle with the Ebola epidemic (2014–2016)

In 2014, an Ebola virus epidemic in Sierra Leone began that widely affected the country,[92] including forcing Sierra Leone to declare a state of emergency.[93] By the end of 2014 there were nearly 3000 deaths and about 10,000 cases of the disease in Sierra Leone.[92] The epidemic also led to the Ouse to Ouse Tock in September 2014, a nationwide three-day quarantine.[94] The epidemic occurred as part of the wider Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa. In early August 2014 Sierra Leone cancelled league football (soccer) matches because of the Ebola epidemic.[95] On 16 March 2016, the World Health Organization declared Sierra Leone to be free from Ebola.[96]

14 August 2017 mudslides

Several mudslides occurred in the early hours of 14 August 2017 in and near the country's capital Freetown.

2018 General election

In 2018, Sierra Leone held a general election. The presidential election, in which neither candidate reached the required threshold of 55%, went to a second round of voting, in which Julius Maada Bio was elected with 51% of the vote.[97]

Geography

Sierra Leone is located on the southwest coast of West Africa, lying mostly between latitudes 7° and 10°N (a small area is south of 7°), and longitudes 10° and 14°W. The country is bordered by Guinea to the north and east, Liberia to the southeast, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west and southwest.[98]

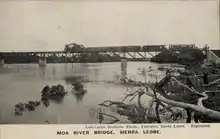

Sierra Leone has a total area of 71,740 km2 (27,699 sq mi), divided into a land area of 71,620 km2 (27,653 sq mi) and water of 120 km2 (46 sq mi).[99] The country has four distinct geographical regions. In eastern Sierra Leone the plateau is interspersed with high mountains, where Mount Bintumani reaches 1,948 m (6,391 ft), the highest point in the country. The upper part of the drainage basin of the Moa River is located in the south of this region.

The centre of the country is a region of lowland plains, containing forests, bush and farmland,[98] that occupies about 43% of Sierra Leone's land area. The northern section of this has been categorised by the World Wildlife Fund as part of the Guinean forest-savanna mosaic ecoregion, while the south is rain-forested plains and farmland.

In the west, Sierra Leone has some 400 km (249 mi) of Atlantic coastline, giving it both bountiful marine resources and attractive tourist potential. The coast has areas of low-lying Guinean mangroves swamp. The national capital Freetown sits on a coastal peninsula, situated next to the Sierra Leone Harbour.

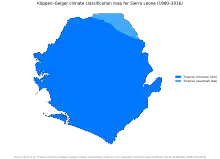

The climate is tropical, with two seasons determining the agricultural cycle: the rainy season from May to November, and a dry season from December to May, which includes harmattan, when cool, dry winds blow in off the Sahara Desert and the night-time temperature can be as low as 16 °C (60.8 °F). The average temperature is 26 °C (78.8 °F) and varies from around 26 to 36 °C (78.8 to 96.8 °F) during the year.[100][101]

Biodiversity

Sierra Leone is home to four terrestrial ecoregions: Guinean montane forests, Western Guinean lowland forests, Guinean forest-savanna mosaic, and Guinean mangroves.[102]

Human activities claimed to be responsible or contributing to land degradation in Sierra Leone include unsustainable agricultural land use, poor soil and water management practices, deforestation, removal of natural vegetation, fuelwood consumption and to a lesser extent overgrazing and urbanisation.[103]

Deforestation, both for commercial timber and to make room for agriculture, is the major concern and represents an enormous loss of natural economic wealth to the nation.[103] Mining and slash and burn for land conversion – such as cattle grazing – dramatically diminished forested land in Sierra Leone since the 1980s. It is listed among countries of concern for emissions, as having Low Forest Cover with High Rates of Deforestation (LFHD).[104] There are concerns that heavy logging continues in the Tama-Tonkoli Forest Reserve in the north. Loggers have extended their operations to Nimini, Kono District, Eastern Province; Jui, Western Rural District, Western Area; Loma Mountains National Park, Koinadougu, Northern Province; and with plans to start operations in the Kambui Forest reserve in the Kenema District, Eastern Province.[104] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 2.76/10, ranking it 154th globally out of 172 countries.[105]

Overfishing is also an issue in Sierra Leone.

Habitat degradation for the African wild dog, Lycaon pictus, has been increased, such that this canid is deemed to have been extirpated in Sierra Leone.[106]

Until 2002, Sierra Leone lacked a forest management system because of the civil war that caused tens of thousands of deaths. Deforestation rates have increased 7.3% since the end of the civil war.[107] On paper, 55 protected areas covered 4.5% of Sierra Leone as of 2003. The country has 2,090 known species of higher plants, 147 mammals, 626 birds, 67 reptiles, 35 amphibians, and 99 fish species.[107] Unrestricted hunting during the war led to the decrease of many animal populations, including elephants, lions, and buffalo. Many of these animals can now only be found in sanctuaries. The tsetse fly, a malaria-carrying mosquito, is now dominant in the region and has led to an increase in the spread of the disease. Still, Sierra Leone’s bird populations have been largely the same and includes native birds such as cuckoos, owls, and vultures. The Tiwai Island Wildlife Sanctuary and the Gola Forest Reserves are just two examples of the humanitarian efforts to preserve wildlife after the civil war.[108]

The Environmental Justice Foundation has documented how the number of illegal fishing vessels in Sierra Leone's waters has multiplied in recent years. The amount of illegal fishing has significantly depleted fish stocks, depriving local fishing communities of an important resource for survival. The situation is particularly serious as fishing provides the only source of income for many communities in a country still recovering from over a decade of civil war.[109]

In June 2005, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and BirdLife International agreed to support a conservation-sustainable development project in the Gola Forest in south eastern Sierra Leone,[110] an important surviving fragment of rainforest in Sierra Leone.

Government and politics

Sierra Leone is a constitutional republic with a directly elected president and a unicameral legislature. The current system of the Government of Sierra Leone is based on the 1991 Sierra Leone Constitution. Sierra Leone has a dominant unitary central government and a weak local government. The executive branch of the Government of Sierra Leone, headed by the president of Sierra Leone has extensive powers and influence. The president is the most powerful government official in Sierra Leone.[111]

Within the confines of the 1991 Constitution, supreme legislative powers are vested in Parliament, which is the law-making body of the nation. Supreme executive authority rests in the president and members of his cabinet and judicial power with the judiciary of which the Chief Justice of Sierra Leone is the head.

The president is the head of state, the head of government, and the commander-in-chief of the Sierra Leone Armed Forces. The president appoints and heads a cabinet of ministers, which must be approved by the Parliament. The president is elected by popular vote to a maximum of two five-year terms. The president is the highest and most influential position within the government of Sierra Leone.

To be elected president of Sierra Leone, a candidate must gain at least 55% of the vote. If no candidate gets 55%, there is a second-round runoff between the top two candidates.

The current president of Sierra Leone is former military junta leader Julius Maada Bio.[112] Bio defeated Samura Kamara of the ruling All People's Congress (APC) in the country's tightly contested 2018 presidential election. Bio replaced outgoing President Ernest Bai Koroma after Bio was sworn into office on 4 April 2018 by Chief Justice Abdulai Cham. Bio is the leader of the Sierra Leone People's Party, the current ruling party in Sierra Leone.

Next to the president is the vice-president, who is the second highest-ranking government official in the executive branch of the Sierra Leone Government. As designated by the Sierra Leone Constitution, the vice-president is to become the new president of Sierra Leone upon the death, resignation, or removal of the President.

Parliament

The Parliament of Sierra Leone is unicameral, with 146 seats. Each of the country's 14 districts is represented in parliament. 132 members are elected concurrently with the presidential elections; the other 16 seats are filled by paramount chiefs from the country's 16 administrative districts.[113] The Sierra Leone parliament is led by the Speaker of Parliament, who is the overall leader of Parliament and is directly elected by sitting members of parliament. The current speaker of the Sierra Leone parliament is Abass Bundu, who was elected by members of parliament on 21 January 2014.

The current members of the Parliament of Sierra Leone were elected in the 2012 Sierra Leone parliamentary election. The APC currently has 68 of the 132 elected parliamentary seats and the Sierra Leone People's Party (SLPP) has 49 of the elected 132 parliamentary seats. Sierra Leone's two most dominant parties, the APC and the SLPP, collectively won every elected seat in Parliament in the 2012 Sierra Leone parliamentary election. To be qualified as a Member of Parliament, the person must be a citizen of Sierra Leone, must be at least 21 years old, and must be able to speak, read, and write the English language with a degree of proficiency to enable him to actively take part in proceedings in Parliament; and must not have any criminal conviction.[111]

Since independence in 1961, Sierra Leone's politics has been dominated by two major political parties: the SLPP and the APC. Other minor political parties have also existed but with no significant support.[114]

Judiciary

The judicial power of Sierra Leone is vested in the judiciary, headed by the Chief Justice of Sierra Leone and comprising the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone, which is the highest court in the country, meaning that its rulings, therefore, cannot be appealed against. Other courts include the High Court of Justice, the Court of Appeal, the magistrate courts, and traditional courts in rural villages. The president appoints and parliament approves Justices for the three courts. The Judiciary has jurisdiction in all civil and criminal matters throughout the country. The current acting chief justice of Sierra Leone is Desmond Babatunde Edwards.

Foreign relations

The Sierra Leonean Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation is responsible for foreign policy of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone has diplomatic relations that include China, Russia,[115] Libya, Iran, and Cuba.

Sierra Leone has good relations with the West, including the United States, and has maintained historical ties with the United Kingdom and other former British colonies through its membership of the Commonwealth of Nations.[116] The United Kingdom has played a major role in providing aid to the former colony, together with administrative help and military training since intervening to end the Civil War in 2000.

Former President Siaka Stevens' government had sought closer relations with other West African countries under the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a policy continued by the current government. Sierra Leone, along with Liberia, Ivory Coast and Guinea, form the Mano River Union (MRU). It is primarily designed to implement development projects and promote regional economic integration between the four countries.[117]

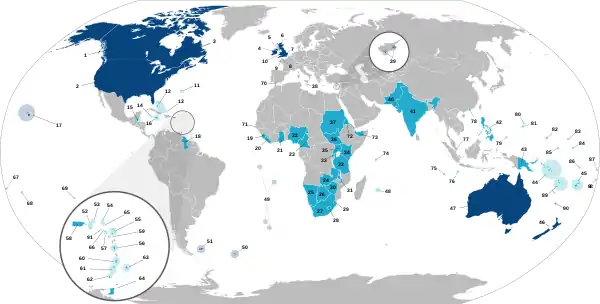

Sierra Leone is also a member of the United Nations and its specialised agencies, the African Union, the African Development Bank (AFDB), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).[118] Sierra Leone is a member of the International Criminal Court with a Bilateral Immunity Agreement of protection for the US military (as covered under Article 98).

Military

The Military of Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces (RSLAF), are the unified armed forces of Sierra Leone responsible for the territorial security of Sierra Leone's border and defending the national interests of Sierra Leone within the framework of its international obligations. The armed forces were formed after independence in 1961, based on elements of the former British Royal West African Frontier Force present in the country. The Sierra Leone Armed Forces consist of around 15,500 personnel, comprising the largest Sierra Leone Army,[119] the Sierra Leone Navy and the Sierra Leone Air Wing.[120]

The president of Sierra Leone is the Commander in Chief of the military and the Minister of Defence responsible for defence policy and the formulation of the armed forces.[121][122]

When Sierra Leone gained independence in 1961, the Royal Sierra Leone Military Force was created from the Sierra Leone Battalion of the West African Frontier Force.[123] The military seized control in 1968, bringing the National Reformation Council into power. On 19 April 1971, when Sierra Leone became a republic, the Royal Sierra Leone Military Forces were renamed the Republic of Sierra Leone Military Force (RSLMF).[123][124] The RSLMF remained a single-service organisation until 1979 when the Sierra Leone Navy was established. In 1995 Defence Headquarters was established, and the Sierra Leone Air Wing was formed. The RSLMF was renamed as the Armed Forces of the Republic of Sierra Leone (AFRSL).

Law enforcement

Law enforcement in Sierra Leone is primarily the responsibility of the Sierra Leone Police (SLP), which is accountable to the Minister of Internal Affairs (appointed by the president). Sierra Leone Police was established by the British colony in 1894; it is one of the oldest police forces in West Africa. It works to prevent crime, protect life and property, detect and prosecute offenders, maintain public order, ensure safety and security, and enhance access to justice. The Sierra Leone Police is headed by the Inspector General of Police, the professional head of the Sierra Leone Police force, who is appointed by the president of Sierra Leone.

Each one of Sierra Leone's 14 districts is headed by a district police commissioner who is the professional head of their respective district. These Police Commissioners report directly to the Inspector General of Police at the Sierra Leone Police headquarters in Freetown. The current Inspector General of Police is William Fayia Sellu, who was appointed to the position by President president Julius Madda Bio on 27 July 2022 to replace Ambrose Sovula, who had been in the post since March 2020.[125][126]

Human rights

Male same-sex sexual activity is illegal under Section 61 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861, and imprisonment for life is possible.[127][128]

Excessive police brutality is also a frequent problem. Protesters have been killed by security forces, as have prison rioters (in one incident at Pademba Road Prison, 30 inmates and one correction officer were killed). Multiple allegations were made during the COVID-19 lockdown period of police attacking people trying to obtain basic necessities.[129]

Leadership in World governance initiatives

Sierra Leone has been one of the signatories of the agreement to convene a convention for drafting a world constitution.[130][131] As a result, in 1968, for the first time in human history, a World Constituent Assembly convened to draft and adopt the Constitution for the Federation of Earth.[132] Milton Margai, then president of Sierra Leone, signed the agreement to convene a World Constituent Assembly.[133]

Administrative divisions

The Republic of Sierra Leone is composed of five regions: the Northern Province, North West Province, Southern Province, the Eastern Province, and the Western Area. Four provinces are further divided into 14 districts; the Western Area is divided into two districts.

The provincial districts are divided into 186 chiefdoms, which have traditionally been led by paramount chiefs, recognised by the British administration in 1896 at the time of organising the Protectorate of Sierra Leone. The Paramount Chiefs are influential, particularly in villages and small rural towns.[134] Each chiefdom has ruling families that were recognised at that time; the Tribal Authority, made up of local notables, elects the paramount chief from the ruling families.[134] Typically, chiefs have the power to "raise taxes, control the judicial system, and allocate land, the most important resource in rural areas".[135]

Within the context of local governance, the districts are governed as localities. Each has a directly elected local district council to exercise authority and carry out functions at a local level.[136][137] In total, there are 19 local councils: 13 district councils, one for each of the 12 districts and one for the Western Area Rural, and six municipalities also have elected local councils. The six municipalities include Freetown, which functions as the local government for the Western Area Urban District, and Bo, Bonthe, Kenema, Koidu, and Makeni.[136][138][139]

While the district councils are under the oversight of their respective provincial administrations, the municipalities are directly overseen by the Ministry of Local Government & Community Development and thus administratively independent of district and provincial administrations.

| District | Area (km2) | Province | Population (2004 census)[140] | Population (2015 census)[141] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bombali District | Makeni | 7,985 | Northern Province | 408,390 | 606,183[142] |

| Koinadugu District | Kabala | 12,121 | 265,758 | 408,097[143] | |

| Port Loko District | Port Loko | 5,719 | 453,746 | 614,063[143] | |

| Tonkolili District | Magburaka | 7,003 | 347,197 | 530,776[144] | |

| Kambia District | Kambia | 3,108 | 270,462 | 343,686[145] | |

| Kenema District | Kenema | 6,053 | Eastern Province | 497,948 | 609,873[146] |

| Kono District | Koidu Town | 5,641 | 335,401 | 505,767[147] | |

| Kailahun District | Kailahun | 3,859 | 358,190 | 525,372[147] | |

| Bo District | Bo | 5,219 | Southern Province | 463,668 | 574,201[148] |

| Bonthe District | Mattru Jong | 3,468 | 139,687 | 200,730[149] | |

| Pujehun District | Pujehun | 4,105 | 228,392 | 345,577 | |

| Moyamba District | Moyamba | 6,902 | 260,910 | 318,064 | |

| Western Area Urban District | Freetown | 13 | Western Area | 772,873 | 1,050,301 |

| Western Area Rural District | Waterloo | 544 | 174,249 | 442,951 |

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

By the 1990s, economic activity was declining and economic infrastructure had become seriously degraded. Over the next decade, much of the formal economy was destroyed in the country's civil war. Since the end of hostilities in January 2002, massive infusions of outside assistance have helped Sierra Leone begin to recover.[150]

Much of the recovery will depend on the success of the government's efforts to limit corruption by officials, which many feel was the chief cause of the civil war. A key indicator of success will be the effectiveness of government management of its diamond sector.

There is high unemployment, particularly among the youth and ex-combatants. Authorities have been slow to implement reforms in the civil service, and the pace of the privatisation programme is also slackening and donors have urged its advancement.

The currency is the leone. The central bank is the Bank of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone operates a floating exchange rate system, and foreign currencies can be exchanged at any of the commercial banks, recognised foreign exchange bureaux and most hotels. Credit card use is limited in Sierra Leone, though they may be used at some hotels and restaurants. There are a few internationally linked automated teller machines that accept Visa cards in Freetown operated by ProCredit Bank.

Agriculture

Two-thirds of the population of Sierra Leone are directly involved in subsistence agriculture.[151] Agriculture accounted for 58 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007.[152]

Agriculture is the largest employer with 80 per cent of the population working in the sector.[153] Rice is the most important staple crop in Sierra Leone with 85 per cent of farmers cultivating rice during the rainy season[154] and an annual consumption of 76 kg per person.[155]

Mining

Rich in minerals, Sierra Leone has relied on mining, especially diamonds, for its economic base. The country is among the top ten diamond producing nations. Mineral exports remain the main currency earner. Sierra Leone is a major producer of gem-quality diamonds. Though rich in diamonds, it has historically struggled to manage their exploitation and export.

Sierra Leone is known for its blood diamonds that were mined and sold to diamond conglomerates during the civil war, to buy the weapons that fuelled its atrocities.[156] In the 1970s and early 1980s, economic growth rate slowed because of a decline in the mining sector and increasing corruption among government officials.

| Rank | Sector | Percentage of GDP |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agriculture | 58.5 |

| 2 | Other services | 10.4 |

| 3 | Trade and tourism | 9.5 |

| 4 | Wholesale and retail trade | 9.0 |

| 5 | Mining and quarrying | 4.5 |

| 6 | Government Services | 4.0 |

| 7 | Manufacturing and handicrafts | 2.0 |

| 8 | Construction | 1.7 |

| 9 | Electricity and water | 0.4 |

Annual production of Sierra Leone's diamond estimates a range between US$250 million–$300 million. Some of that is smuggled, where it is possibly used for money laundering or financing illicit activities. Formal exports have dramatically improved since the civil war, with efforts to improve the management of them having some success. In October 2000, a UN-approved certification system for exporting diamonds from the country was put in place which led to a dramatic increase in legal exports. In 2001, the government created a mining community development fund (DACDF), which returns a portion of diamond export taxes to diamond mining communities. The fund was created to raise local communities' stakes in the legal diamond trade.

Sierra Leone has one of the world's largest deposits of rutile, a titanium ore used as paint pigment and welding rod coatings.

Transport infrastructure

There are several systems of transport in Sierra Leone, which has a road, air and water infrastructure, including a network of highways and several airports. There are 11,300 kilometres (7,000 miles) of highways in Sierra Leone, of which 904 km (562 mi)[99] are paved (about 8% of the roads). Sierra Leone's highways are linked to Conakry, Guinea, and Monrovia, Liberia.

Sierra Leone has the largest natural harbour on the African continent, allowing international shipping through the Queen Elizabeth II Quay in the Cline Town area of eastern Freetown or through Government Wharf in central Freetown. There are 800 km (497 mi) of waterways in Sierra Leone, of which 600 km (373 mi) are navigable year-round. Major port cities are Bonthe, Freetown, Sherbro Island and Pepel.