Federal Republic of Somalia | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Qolobaa Calankeed علم أي امة "Every nation has its own flag" | |

.svg.png.webp) Federal Republic of Somalia | |

| Capital and largest city | Mogadishu 2°2′N 45°21′E / 2.033°N 45.350°E |

| Official languages | Somali, Arabic[1] |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion | Sunni Islam (official)[1] |

| Demonym(s) | Somali[1] |

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Hassan Sheikh Mohamud | |

| Hamza Abdi Barre | |

| Abdi Hashi Abdullahi | |

| Aden Madobe | |

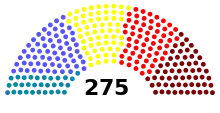

| Legislature | Federal Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of the People | |

| Independence from Italy and the United Kingdom | |

| 1887 | |

| 1889 | |

| 1 July 1960 | |

| 20 September 1960 | |

| 1 August 2012 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 637,657[1] km2 (246,201 sq mi) (43rd) |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 12,693,796[3] (78th) |

• Density | 27.2[4]/km2 (70.4/sq mi) (199th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2021) | low · 192nd |

| Currency | Somali shilling (SOS) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +252 |

| ISO 3166 code | SO |

| Internet TLD | .so |

Somalia,[lower-alpha 2] officially the Federal Republic of Somalia[10] (Somali: Jamhuuriyadda Federaalka Soomaaliya; Arabic: جمهورية الصومال الفيدرالية), is a country in the Horn of Africa. The country is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti[11] to the northwest, the Gulf of Aden to the north, the Indian Ocean to the east, and Kenya to the southwest. Somalia has the longest coastline on Africa's mainland.[12] Its terrain consists mainly of plateaus, plains, and highlands.[1] Hot conditions prevail year-round, with periodic monsoon winds and irregular rainfall.[13] Somalia has an estimated population of around 17.1 million,[14][15] of which over 2 million live in the capital and largest city Mogadishu, and has been described as Africa's most culturally homogeneous country.[16][17] Around 85% of its residents are ethnic Somalis,[1] who have historically inhabited the country's north. Ethnic minorities are largely concentrated in the south.[18] The official languages of Somalia are Somali and Arabic.[1] Most people in the country are Muslims,[19] the majority of them Sunni.[20]

In antiquity, Somalia was an important commercial center.[21][22] It is among the most probable locations of the ancient Land of Punt.[23][24][25] During the Middle Ages, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade, including the Imamate of Awsame, Ajuran Sultanate, the Adal Sultanate, and the Sultanate of the Geledi.

In the late 19th century, Somali Sultanates like the Isaaq Sultanate,[26] Habr Yunis Sultanate and the Majeerteen Sultanate were colonized by both the Italian and British Empires.[27][28][29] European colonists merged the tribal territories into two colonies, which were Italian Somaliland and the British Somaliland Protectorate.[30][31] Meanwhile, in the interior, the Dervishes led by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan engaged in a two-decade confrontation against Abyssinia, Italian Somaliland, and British Somaliland and were finally defeated in the 1920 Somaliland Campaign.[32][33][34] Italy acquired full control of the northeastern, central, and southern parts of the area after successfully waging the Campaign of the Sultanates against the ruling Majeerteen Sultanate and Sultanate of Hobyo.[31] In 1960, the two territories united to form the independent Somali Republic under a civilian government.[35]

Siad Barre of the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) seized power in 1969 and established the Somali Democratic Republic, brutally attempting to squash the Somaliland War of Independence in the north of the country.[36] The SRC collapsed in 1991 with the onset of the Somali Civil War.[37]

Since the onset of the civil war, which involves various warring groups, most regions of Somalia have returned to customary and religious law. In the early 2000s, a number of interim federal administrations were created. The Transitional National Government (TNG) was established in 2000, followed by the formation of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in 2004, which reestablished the Somali Armed Forces.[1][38]

In 2006, with a US-backed Ethiopian intervention, the TFG assumed control of most of the nation's southern conflict zones from the newly formed Islamic Courts Union (ICU). The ICU subsequently splintered into more radical groups, including the jihadist group al-Shabaab, which battled the TFG and its AMISOM allies for control of the region.[1] By mid-2012, the insurgents had lost most of the territory they had seized, and a search for more permanent democratic institutions began.[39] Despite this, insurgents still control much of central and southern Somalia,[40][41] and wield influence in government-controlled areas,[41] with the town of Jilib acting as the insurgents' de facto capital.[40][42] A new provisional constitution was passed in August 2012,[43][44] reforming Somalia as a federation.[45] The same month, the Federal Government of Somalia was formed[46] and a period of reconstruction began in Mogadishu, despite al-Shabaab frequently carrying out attacks there.[39][47]

Somalia's GDP per capita is one of the world's lowest, and it belongs to the least developed country group.[48] In 2019, Somalia had the lowest HDI in the world, and in the same year, 69% of Somalia's population was living below the poverty line.[49] As of 2020, Somalia is placed the second highest in the Fragile States Index.[50] It has maintained an informal economy mainly based on livestock, remittances from Somalis working abroad, and telecommunications.[51] It is a member of the United Nations,[52] the Arab League,[53] African Union,[54] Non-Aligned Movement,[55] East African Community,[56] and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.[57]

History

Prehistory

Somalia was likely one of the first lands to be settled by early humans due to its location. Hunter-gatherers who would later migrate out of Africa likely settled here before their migrations.[58] During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here.[59][60][61][58][62][63] The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BCE.[64] The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artifacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.[65]

According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[66] or the Near East.[67]

The Laas Geel complex on the outskirts of Hargeisa in northwestern Somalia dates back approximately 5,000 years, and has rock art depicting both wild animals and decorated cows.[68] Other cave paintings are found in the northern Dhambalin region, which feature one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is dated to 1,000 to 3,000 BCE.[69][70] Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo in northern Somalia lies Karinhegane, the site of numerous cave paintings of both real and mythical animals. Each painting has an inscription below it, which collectively have been estimated to be around 2,500 years old.[71][72]

Antiquity and classical era

Ancient pyramidical structures, mausoleums, ruined cities and stone walls, such as the Wargaade Wall, are evidence of an old civilization that once thrived in the Somali peninsula.[73][74] This civilization enjoyed a trading relationship with ancient Egypt and Mycenaean Greece since the second millennium BCE, supporting the hypothesis that Somalia or adjacent regions were the location of the ancient Land of Punt.[73][75] The Puntites native to the region traded myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory and frankincense with the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Indians, Chinese and Romans through their commercial ports. An Egyptian expedition sent to Punt by the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut is recorded on the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, during the reign of the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati.[73] In 2015, isotopic analysis of ancient baboon mummies from Punt that had been brought to Egypt as gifts indicated that the specimens likely originated from an area encompassing eastern Somalia and the Eritrea-Ethiopia corridor.[76]

In the classical era, the Macrobians, who may have been ancestral to Somalis, established a powerful tribal kingdom that ruled large parts of modern Somalia. They were reputed for their longevity and wealth, and were said to be the "tallest and handsomest of all men".[77] The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the Persian Emperor Cambyses II, upon his conquest of Egypt in 525 BC, sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based on his stature and beauty, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to draw it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.[77][78] The Macrobians were a regional power reputed for their advanced architecture and gold wealth, which was so plentiful that they shackled their prisoners in golden chains.[78] The camel is believed to have been domesticated in the Horn region sometime between the 2nd and 3rd millennium BCE. From there, it spread to Egypt and the Maghreb.[79]

During the classical period, the Barbara city-states also known as sesea of Mosylon, Opone, Mundus, Isis, Malao, Avalites, Essina, Nikon and Sarapion developed a lucrative trade network, connecting with merchants from Ptolemaic Egypt, Ancient Greece, Phoenicia, Parthian Persia, Saba, the Nabataean Kingdom, and the Roman Empire. They used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants agreed with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula[80] to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas.[81] However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from Roman interference.[82] For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from Ceylon and the Spice Islands. The source of the cinnamon and other spices is said to have been the best-kept secret of Arab and Somali merchants in their trade with the Roman and Greek world; the Romans and Greeks believed the source to have been the Somali peninsula.[83] The collusive agreement among Somali and Arab traders inflated the price of Indian and Chinese cinnamon in North Africa, the Near East, and Europe, and made the cinnamon trade a very profitable revenue generator, especially for the Somali merchants through whose hands large quantities were shipped across sea and land routes.[81]

Birth of Islam and the Middle Ages

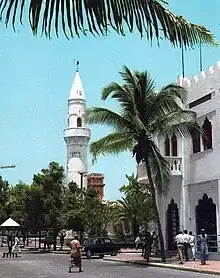

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca fleeing prosecution during the first Hejira with Masjid al-Qiblatayn in Zeila being built before the Qiblah towards Mecca. It is one of the oldest mosques in Africa.[84] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard.[85] He also mentioned that the Adal Kingdom had its capital in the city.[85][86] According to Leo Africanus, the Adal Sultanate was governed by local Somali dynasties and its realm encompassed the geographical area between the Bab el Mandeb and Cape Guardafui. It was thus flanked to the south by the Ajuran Empire and to the west by the Abyssinian Empire.[87]

Throughout the Middle Ages, Arab immigrants arrived in Somaliland, a historical experience which would later lead to the legendary stories about Muslim sheikhs such as Daarood and Ishaaq bin Ahmed (the purported ancestors of the Darod and Isaaq clans, respectively) travelling from Arabia to Somalia and marrying into the local Dir clan.[88]

In 1332, the Zeila-based King of Adal was slain in a military campaign aimed at halting Abyssinian emperor Amda Seyon I's march toward the city.[89] When the last Sultan of Ifat, Sa'ad ad-Din II, was also killed by Emperor Dawit I in Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to Yemen, before returning in 1415.[90] In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of Dakkar, where Sabr ad-Din II, the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new base after his return from Yemen.[91][92]

Adal's headquarters were again relocated the following century, this time southward to Harar. From this new capital, Adal organised an effective army led by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad "Gurey" or "Gran"; both meaning "the left-handed") and his closest top general Garad Hirabu "Emir Of The Somalis that invaded the Abyssinian empire.[92] This 16th-century campaign is historically known as the Conquest of Abyssinia (Futuh al-Habash). During the war, Imam Ahmad pioneered the use of cannons supplied by the Ottoman Empire, which he imported through Zeila and deployed against Abyssinian forces and their Portuguese allies led by Cristóvão da Gama.[93] Some scholars argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms such as the matchlock musket, cannon, and the arquebus over traditional weapons.[94]

During the Ajuran Sultanate period, the city-states and republics of Merca, Mogadishu, Barawa, Hobyo and their respective ports flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and from Arabia, India, Venetia,[95] Persia, Egypt, Portugal, and as far away as China. Vasco da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses several storeys high and large palaces in its centre, in addition to many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[96] The Harla, an early Hamitic group of tall stature who inhabited parts of Somalia, Tchertcher and other areas in the Horn, also erected various tumuli.[97] These masons are believed to have been ancestral to ethnic Somalis.[98]

In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with cloth and spices, for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[99] Mogadishu, the center of a thriving textile industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt, among other places[100]), together with Merca and Barawa, also served as a transit stop for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[101] Jewish merchants from the Hormuz brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[102]

Trading relations were established with Malacca in the 15th century,[103] with cloth, ambergris and porcelain being the main commodities of the trade.[104] Giraffes, zebras and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between East Asia and the Horn.[105] Hindu merchants from Surat and Southeast African merchants from Pate, seeking to bypass both the Portuguese India blockade ( and later the Omani interference), used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were out of the two powers' direct jurisdiction) to conduct their trade in safety and without interference.[106]

Early modern era and the scramble for Africa

In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate and Ajuran Sultanate began to flourish in Somalia. These included the Hiraab Imamate, Habr Yunis Sultanate led by the Ainanshe dynasty,[27] the Sultanate of the Geledi (Gobroon dynasty), the Majeerteen Sultanate (Migiurtinia), and the Sultanate of Hobyo (Obbia). They continued the tradition of castle-building and seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires.

Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, the third Sultan of the House of Gobroon, started the golden age of the Gobroon Dynasty. His army came out victorious during the Bardheere Jihad, which restored stability in the region and revitalized the East African ivory trade. He also had cordial relations and received gifts from the rulers of neighbouring and distant kingdoms such as the Omani, Witu and Yemeni Sultans.

Sultan Ibrahim's son Ahmed Yusuf succeeded him as one of the most important figures in 19th-century East Africa, receiving tribute from Omani governors and creating alliances with important Muslim families on the East African coast. In Somalland, the Isaaq Sultanate was established in 1750. The Isaaq Sultanate was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. It spanned the territories of the Isaaq clan, descendants of the Banu Hashim clan,[107] in modern-day Somaliland and Ethiopia. The sultanate was governed by the Rer Guled branch established by the first sultan, Sultan Guled Abdi, of the Eidagale clan. The sultanate is the pre-colonial predecessor to the modern Republic of Somaliland.[108][109][110]

According to oral tradition, prior to the Guled dynasty the Isaaq clan-family were ruled by a dynasty of the Tolje'lo branch starting from, descendants of Ahmed nicknamed Tol Je'lo, the eldest son of Sheikh Ishaaq's Harari wife. There were eight Tolje'lo rulers in total, starting with Boqor Harun (Somali: Boqor Haaruun) who ruled the Isaaq Sultanate for centuries starting from the 13th century.[111][112] The last Tolje'lo ruler Garad Dhuh Barar (Somali: Dhuux Baraar) was overthrown by a coalition of Isaaq clans. The once strong Tolje'lo clan were scattered and took refuge amongst the Habr Awal with whom they still mostly live.[113][114]

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin Conference of 1884, European powers began the Scramble for Africa. In that year, a British protectorate was declared over part of Somalia, on the African coast opposite South Yemen.[115] Initially, this region was under the control of the Indian Office, and so administered as part of the Indian Empire; in 1898 it was transferred to control by London.[115] In 1889, the protectorate and later colony of Italian Somalia was officially established by Italy through various treaties signed with a number of chiefs and sultans;[116] Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid first sent a request to Italy in late December 1888 to make his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian protectorate before later signing a treaty in 1889.[117]

The Dervish movement successfully repulsed the British Empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region.[118] The Darawiish defeated the Italian, British, Abyssinian colonial powers on numerous occasions, most notably, the 1903 victory at Cagaarweyne commanded by Suleiman Aden Galaydh,[119] forcing the British Empire to retreat to the coastal region in the late 1900s.[120] The Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 by British airpower.[121]

The dawn of fascism in the early 1920s heralded a change of strategy for Italy, as the north-eastern sultanates were soon to be forced within the boundaries of La Grande Somalia ("Greater Somalia") according to the plan of Fascist Italy. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi on 15 December 1923, things began to change for that part of Somaliland known as Italian Somaliland. The last piece of land acquired by Italy in Somalia was Oltre Giuba, present-day Jubaland region, in 1925.[117]

The Italians began local infrastructure projects, including the construction of hospitals, farms and schools.[122] Fascist Italy, under Benito Mussolini, attacked Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935, with an aim to colonize it. The invasion was condemned by the League of Nations, but little was done to stop it or to liberate occupied Ethiopia. In 1936, Italian Somalia was integrated into Italian East Africa, alongside Eritrea and Ethiopia, as the Somalia Governorate. On 3 August 1940, Italian troops, including Somali colonial units, crossed from Ethiopia to invade British Somaliland, and by 14 August, succeeded in taking Berbera from the British.

A British force, including troops from several African countries, launched the campaign in January 1941 from Kenya to liberate British Somaliland and Italian-occupied Ethiopia and conquer Italian Somaliland. By February most of Italian Somaliland was captured and, in March, British Somaliland was retaken from the sea. The forces of the British Empire operating in Somaliland comprised the three divisions of South African, West African, and East African troops. They were assisted by Somali forces led by Abdulahi Hassan with Somalis of the Isaaq, Dhulbahante, and Warsangali clans prominently participating. The number of Italian Somalis began to decline after World War II, with fewer than 10,000 remaining in 1960.[123]

Independence (1960–1969)

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland as protectorates. In 1945, during the Potsdam Conference, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland as the Trust Territory of Somaliland, on the condition first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL)—that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.[124][125] British Somaliland remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.[123]

To the extent that Italy held the territory by UN mandate, the trusteeship provisions gave the Somalis the opportunity to gain experience in Western political education and self-government. These were advantages that British Somaliland, which was to be incorporated into the new Somali state, did not have. Although in the 1950s British colonial officials attempted, through various administrative development efforts, to make up for past neglect, the protectorate stagnated in political administrative development. The disparity between the two territories in economic development and political experience would later cause serious difficulties integrating the two parts.[126]

Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,[127] the British returned the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was presumably protected by British treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the Somali Region to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somali territory to the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik in exchange for his help against possible advances by the French.[128]

Britain included the conditional provision that the Somali residents would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over the area. This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to buy back the Somali lands it had turned over.[124] Britain also granted administration of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited Northern Frontier District (NFD) to Kenyan nationalists.[129][130] This was despite a plebiscite in which, according to a British colonial commission, almost all of the territory's ethnic Somalis favored joining the newly formed Somali Republic.[131]

A referendum was held in neighbouring Djibouti (then known as French Somaliland) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, largely due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans.[132] There was also widespread vote rigging, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.[133]

The majority of those who voted 'no' were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia, as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later.[132] Djibouti finally gained independence from France in 1977, and Hassan Gouled Aptidon, a Somali who had campaigned for a 'yes' vote in the referendum of 1976, eventually became Djibouti's first president (1977–1999).[132]

On 1 July 1960, five days after the former British Somaliland protectorate obtained independence as the State of Somaliland, the territory united with the Trust Territory of Somaliland to form the Somali Republic,[134] albeit within boundaries drawn up by Italy and Britain.[135][136] A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa and Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal with other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments, with Abdulcadir Muhammed Aden as President of the Somali National Assembly, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as President of the Somali Republic, and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister (later to become president from 1967 to 1969). On 20 July 1961 and through a popular referendum, was ratified popularly by the people of Somalia under Italian trusteeship, Most of the people from the former Somaliland Protectorate did not participate in the referendum, although only a small number of Somalilanders who participated the referendum voted against the new constitution,[137] which was first drafted in 1960.[35] In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke. Egal would later become the President of the autonomous Somaliland region in northwestern Somalia.

On 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on 21 October 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[138]

Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1991)

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Brigadier General Mohamed Ainanshe Guled, Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Kediye officially held the title "Father of the Revolution", and Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC.[139] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[140][141] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[142]

The revolutionary army established large-scale public works programs and successfully implemented an urban and rural literacy campaign, which helped dramatically increase the literacy rate. In addition to a nationalization program of industry and land, the new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab world, eventually joining the Arab League in February, 1974.[143] That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the African Union (AU).[144]

In July 1976, Barre's SRC disbanded itself and established in its place the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP), a one-party government based on scientific socialism and Islamic tenets. The SRSP was an attempt to reconcile the official state ideology with the official state religion by adapting Marxist precepts to local circumstances. Emphasis was placed on the Muslim principles of social progress, equality and justice, which the government argued formed the core of scientific socialism and its own accent on self-sufficiency, public participation and popular control, as well as direct ownership of the means of production. While the SRSP encouraged private investment on a limited scale, the administration's overall direction was essentially communist.[142]

In July 1977, the Ogaden War broke out after Barre's government used a plea for national unity to justify an aggressive incorporation of the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region of Ethiopia into a Pan-Somali Greater Somalia, along with the rich agricultural lands of south-eastern Ethiopia, infrastructure, and strategically important areas as far north as Djibouti.[145] In the first week of the conflict, Somali armed forces took southern and central Ogaden and for most of the war, the Somali army scored continuous victories on the Ethiopian army and followed them as far as Sidamo. By September 1977, Somalia controlled 90% of the Ogaden and captured strategic cities such as Jijiga and put heavy pressure on Dire Dawa, threatening the train route from the latter city to Djibouti. After the siege of Harar, a massive unprecedented Soviet intervention consisting of 20,000 Cuban forces and several thousand Soviet experts came to the aid of Ethiopia's communist Derg regime. By 1978, the Somali troops were ultimately pushed out of the Ogaden. This shift in support by the Soviet Union motivated the Barre government to seek allies elsewhere. It eventually settled on the Soviets' Cold War arch-rival, the United States, which had been courting the Somali government for some time. All in all, Somalia's initial friendship with the Soviet Union and later partnership with the United States enabled it to build the largest army in Africa.[146]

A new constitution was promulgated in 1979 under which elections for a People's Assembly were held. However, Barre's Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party politburo continued to rule.[141] In October 1980, the SRSP was disbanded, and the Supreme Revolutionary Council was re-established in its place.[142] By that time, Barre's government had become increasingly unpopular. Many Somalis had become disillusioned with life under military dictatorship.

The regime was weakened further in the 1980s as the Cold War drew to a close and Somalia's strategic importance was diminished. The government became increasingly authoritarian, and resistance movements, encouraged by Ethiopia, sprang up across the country, eventually leading to the Somali Civil War. Among the militia groups were the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), United Somali Congress (USC), Somali National Movement (SNM) and the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM), together with the non-violent political oppositions of the Somali Democratic Movement (SDM), the Somali Democratic Alliance (SDA) and the Somali Manifesto Group (SMG).

Somalia Civil War

As the moral authority of Barre's government was gradually eroded, many Somalis became disillusioned with life under military rule. By the mid-1980s, resistance movements supported by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration had sprung up across the country. Barre responded by ordering punitive measures against those he perceived as locally supporting the guerrillas, especially in the northern regions. The clampdown included bombing of cities, with the northwestern administrative centre of Hargeisa, a Somali National Movement (SNM) stronghold, among the targeted areas in 1988.[147][148] The bombardment was led by General Mohammed Said Hersi Morgan, Barre's son-in-law.[149]

During 1990, in the capital city of Mogadishu, the residents were prohibited from gathering publicly in groups greater than three or four. Fuel shortages caused long lines of cars at petrol stations. Inflation had driven the price of pasta (ordinary dry Italian noodles, a staple at that time) to five U.S. dollars per kilogram. The price of khat, imported daily from Kenya, was also five U.S. dollars per standard bunch. Paper currency notes were of such low value that several bundles were needed to pay for simple restaurant meals.

A thriving black market existed in the centre of the city as banks experienced shortages of local currency for exchange. At night, the city of Mogadishu lay in darkness. Close monitoring of all visiting foreigners was in effect. Harsh exchange control regulations were introduced to prevent export of foreign currency. Although no travel restrictions were placed on foreigners, photographing many locations was banned. During daytime in Mogadishu, the appearance of any government military force was extremely rare. Alleged late-night operations by government authorities, however, included "disappearances" of individuals from their homes.[150]

In 1991, the Barre administration was ousted by a coalition of clan-based opposition groups, backed by Ethiopia's then-ruling Derg regime and Libya.[151] Following a meeting of the Somali National Movement and northern clans' elders, the northern former British portion of the country declared its independence as the Republic of Somaliland in May 1991. Although de facto independent and relatively stable compared to the tumultuous south, it has not been recognized by any foreign government.[152][153]

Many of the opposition groups subsequently began competing for influence in the power vacuum that followed the ouster of Barre's regime. In the south, armed factions led by USC commanders General Mohamed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Mohamed, in particular, clashed as each sought to exert authority over the capital.[155] In 1991, a multi-phased international conference on Somalia was held in neighbouring Djibouti. Aidid boycotted the first meeting in protest.[156]

Owing to the legitimacy bestowed on Muhammad by the Djibouti conference, he was subsequently recognized by the international community as the new President of Somalia. Djibouti, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Italy were among the countries that officially extended recognition to Muhammad's administration.[156] He was not able to exert his authority beyond parts of the capital. Power was instead vied with other faction leaders in the southern half of Somalia and with autonomous sub-national entities in the north.[157] The Djibouti conference was followed by two abortive agreements for national reconciliation and disarmament, which were signed by 15 political stakeholders: an agreement to hold an Informal Preparatory Meeting on National Reconciliation, and the 1993 Addis Ababa Agreement made at the Conference on National Reconciliation.

In the early 1990s, due to the protracted lack of a permanent central authority, Somalia began to be characterized as a "failed state".[158][159][160] Political scientist Ken Menkhaus argues that evidence suggested that the nation had already attained failed state status by the mid-1980s,[161] while Robert I. Rotberg similarly posits that the state failure had preceded the ouster of the Barre administration.[162] Hoehne (2009), Branwen (2009) and Verhoeven (2009) also used Somalia during this period as a case study to critique various aspects of the "state failure" discourse.[163]

Transitional institutions

The Transitional National Government (TNG) was established in April–May 2000 at the Somalia National Peace Conference (SNPC) held in Arta, Djibouti. Abdiqasim Salad Hassan was selected as the President of the nation's new Transitional National Government (TNG), an interim administration formed to guide Somalia to its third permanent republican government.[164] The TNG's internal problems led to the replacement of the Prime Minister four times in three years, and the administrative body's reported bankruptcy in December 2003. Its mandate ended at the same time.[165]

On 10 October 2004, legislators elected Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed as the first President of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG), the Transitional National Government's successor.[166] the TFG was the second interim administration aiming to restore national institutions to Somalia after the 1991 collapse of the Siad Barre regime and the ensuing civil war.[167]

The Transitional Federal Government (TFG) was the internationally recognised government of Somalia until 20 August 2012, when its tenure officially ended.[46] It was established as one of the Transitional Federal Institutions (TFIs) of government as defined in the Transitional Federal Charter (TFC) adopted in November 2004 by the Transitional Federal Parliament (TFP). The Transitional Federal Government officially comprised the executive branch of government, with the TFP serving as the legislative branch. The government was headed by the President of Somalia, to whom the cabinet reported through the Prime Minister. However, it was also used as a general term to refer to all three branches collectively.

Islamic Courts Union

In 2006, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), assumed control of much of the southern part of the country for 6 months and imposed Shari'a law. Top UN officials have referred to this brief period as a 'Golden era' in the history of Somali politics.[168][169]

Transitional Federal Government

The Transitional Federal Government sought to re-establish its authority, and, with the assistance of Ethiopian troops, African Union peacekeepers and air support by the United States, drove out the ICU and solidified its rule.[170] On 8 January 2007, TFG President Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed entered Mogadishu with the Ethiopian military support for the first time since being elected to office. The government then relocated to Villa Somalia in the capital from its interim location in Baidoa. This marked the first time since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991 that the federal government controlled most of the country.[171]

Al Shabaab insurgency

Al-Shabaab opposed the Ethiopian military's presence in Somalia and continued an insurgency against the TFG. Throughout 2007 and 2008, Al-Shabaab scored military victories, seizing control of key towns and ports in both central and southern Somalia. By January 2009, Al-Shabaab and other militias had forced the Ethiopian troops to retreat, leaving behind an under-equipped African Union peacekeeping force to assist the Transitional Federal Government's troops.[172]

Owing to a lack of funding and human resources, an arms embargo that made it difficult to re-establish a national security force, and general indifference on the part of the international community, Yusuf found himself obliged to deploy thousands of troops from Puntland to Mogadishu to sustain the battle against insurgent elements in the southern part of the country. Financial support for this effort was provided by the autonomous region's government. This left little revenue for Puntland's own security forces and civil service employees, leaving the territory vulnerable to piracy and terrorist attacks.[173][174]

On 29 December 2008, Yusuf announced before a united parliament in Baidoa his resignation as President of Somalia. In his speech, which was broadcast on national radio, Yusuf expressed regret at failing to end the country's seventeen-year conflict as his government had been mandated to do.[175] He also blamed the international community for their failure to support the government, and said that the speaker of parliament would succeed him in office per the Charter of the Transitional Federal Government.[176]

End of transitional period

Between 31 May and 9 June 2008, representatives of Somalia's federal government and the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia (ARS) participated in peace talks in Djibouti brokered by the former United Nations Special Envoy to Somalia, Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah. The conference ended with a signed agreement calling for the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops in exchange for the cessation of armed confrontation. Parliament was subsequently expanded to 550 seats to accommodate ARS members, which then elected Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, as president.[1]

.svg.png.webp)

With the help of a small team of African Union troops, the TFG began a counteroffensive in February 2009 to assume full control of the southern half of the country. To solidify its rule, the TFG formed an alliance with the Islamic Courts Union, other members of the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia, and Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a, a moderate Sufi militia.[177] Furthermore, Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam, the two main Islamist groups in opposition, began to fight amongst themselves in mid-2009.[178] As a truce, in March 2009, the TFG announced that it would re-implement Shari'a as the nation's official judicial system.[179] However, conflict continued in the southern and central parts of the country. Within months, the TFG had gone from holding about 70% of south-central Somalia's conflict zones, to losing control of over 80% of the disputed territory to the Islamist insurgents.[171]

In October 2011, a coordinated operation, Operation Linda Nchi between the Somali and Kenyan militaries and multinational forces began against the Al-Shabaab in southern Somalia.[180][181] By September 2012, Somali, Kenyan, and Raskamboni forces had managed to capture Al-Shabaab's last major stronghold, the southern port of Kismayo.[182] In July 2012, three European Union operations were launched to engage with Somalia: EUTM Somalia, EU Naval Force Somalia Operation Atalanta off the Horn of Africa, and EUCAP Nestor.[183]

As part of the official "Roadmap for the End of Transition", a political process that provided clear benchmarks leading toward the formation of permanent democratic institutions in Somalia, the Transitional Federal Government's interim mandate ended on 20 August 2012.[39] The Federal Parliament of Somalia was concurrently inaugurated.[46]

Federal government

The Federal Government of Somalia, the first permanent central government in the country since the start of the civil war, was established in August 2012. In August 2014, the Somali government-led Operation Indian Ocean was launched against insurgent-held pockets in the countryside.[184]

Geography

Somalia is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, the Gulf of Aden to the north, the Somali Sea and Guardafui Channel to the east, and Kenya to the southwest. With a land area of 637,657 square kilometers, Somalia's terrain consists mainly of plateaus, plains and highlands.[185] Its coastline is more than 3,333 kilometers in length, the longest of mainland Africa.[12] It has been described as being roughly shaped "like a tilted number seven".[186]

In the far north, the rugged east–west ranges of the Ogo Mountains lie at varying distances from the Gulf of Aden coast. Hot conditions prevail year-round, along with periodic monsoon winds and irregular rainfall.[13] Geology suggests the presence of valuable mineral deposits. Somalia is separated from Seychelles by the Somali Sea and is separated from Socotra by the Guardafui Channel.

Administrative divisions

Somalia is officially divided into eighteen regions (gobollada, singular gobol),[1] which in turn are subdivided into districts. The regions are:

| Region | Area (km2) | Population | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awdal | 21,374 | 1,010,566 | Borama |

| Bari | 70,088 | 719,512 | Bosaso |

| Nugal | 26,180 | 392,697 | Garowe |

| Mudug | 72,933 | 717,863 | Galkayo |

| Galguduud | 46,126 | 569,434 | Dusmareb |

| Hiran | 31,510 | 520,685 | Beledweyne |

| Middle Shabelle | 22,663 | 516,036 | Jowhar |

| Banaadir | 370 | 1,650,227 | Mogadishu |

| Lower Shabelle | 25,285 | 1,202,219 | Barawa |

| Togdheer | 38,663 | 721,363 | Burao |

| Bakool | 26,962 | 367,226 | Xuddur |

| Woqooyi Galbeed | 28,836 | 1,242,003 | Hargeisa |

| Bay | 35,156 | 792,182 | Baidoa |

| Gedo | 60,389 | 508,405 | Garbahaarreey |

| Middle Juba | 9,836 | 362,921 | Bu'aale |

| Lower Juba | 42,876 | 489,307 | Kismayo |

| Sanaag | 53,374 | 544,123 | Erigavo |

| Sool | 25,036 | 327,428 | Las Anod |

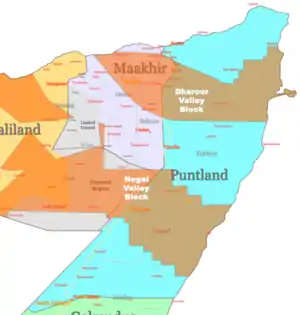

Northern Somalia is now de facto divided up among the autonomous regions of Puntland (which considers itself an autonomous state), Somaliland (a self-declared but unrecognized state) and newly established Khatumo State of Somalia. In central Somalia, Galmudug is another regional entity that emerged just south of Puntland. Jubaland in the far south is a fourth autonomous region within the federation.[1] In 2014, a new South West State was likewise established.[187] In April 2015, a formation conference was also launched for a new Hirshabelle State.[188]

The Federal Parliament is tasked with selecting the ultimate number and boundaries of the autonomous regional states (officially Federal Member States) within the Federal Republic of Somalia.[189][190]

Location

Somalia is bordered by Kenya to the southwest, the Gulf of Aden to the north, the Guardafui Channel and Indian Ocean to the east, and Ethiopia to the west. The country borders Djibouti. It lies between latitudes 2°S and 12°N, and longitudes 41° and 52°E. Strategically located at the mouth of the Bab el Mandeb gateway to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, the country occupies the tip of a region that, due to its resemblance on the map to a rhinoceros' horn, is commonly referred to as the Horn of Africa.[1][191]

Waters

Somalia has the longest coastline on the mainland of Africa,[192] with a seaboard that stretches 3,333 kilometres (2,071 mi). Its terrain consists mainly of plateaus, plains and highlands. The nation has a total area of 637,657 square kilometres (246,201 sq mi) of which constitutes land, with 10,320 square kilometres (3,980 sq mi) of water. Somalia's land boundaries extend to about 2,340 kilometres (1,450 mi); 58 kilometres (36 mi) of that is shared with Djibouti, 682 kilometres (424 mi) with Kenya, and 1,626 kilometres (1,010 mi) with Ethiopia. Its maritime claims include territorial waters of 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi).[1]

Somalia has several islands and archipelagos on its coast, including the Bajuni Islands and the Saad ad-Din Archipelago: see islands of Somalia.

Habitat

Somalia contains seven terrestrial ecoregions: Ethiopian montane forests, Northern Zanzibar–Inhambane coastal forest mosaic, Somali Acacia–Commiphora bushlands and thickets, Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands, Hobyo grasslands and shrublands, Somali montane xeric woodlands, and East African mangroves.[193]

In the north, a scrub-covered, semi-desert plain referred as the Guban lies parallel to the Gulf of Aden littoral. With a width of twelve kilometres in the west to as little as two kilometres in the east, the plain is bisected by watercourses that are essentially beds of dry sand except during the rainy seasons. When the rains arrive, the Guban's low bushes and grass clumps transform into lush vegetation.[191] This coastal strip is part of the Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands ecoregion.

Cal Madow is a mountain range in the northeastern part of the country. Extending from several kilometres west of the city of Bosaso to the northwest of Erigavo, it features Somalia's highest peak, Shimbiris, which sits at an elevation of about 2,416 metres (7,927 ft).[1] The rugged east–west ranges of the Karkaar Mountains also lie to the interior of the Gulf of Aden littoral.[191] In the central regions, the country's northern mountain ranges give way to shallow plateaus and typically dry watercourses that are referred to locally as the Ogo. The Ogo's western plateau, in turn, gradually merges into the Haud, an important grazing area for livestock.[191]

Somalia has only two permanent rivers, the Jubba and Shabele, both of which begin in the Ethiopian Highlands. These rivers mainly flow southwards, with the Jubba River entering the Indian Ocean at Kismayo. The Shabele River at one time apparently used to enter the sea near Merca, but now reaches a point just southwest of Mogadishu. After that, it consists of swamps and dry reaches before finally disappearing in the desert terrain east of Jilib, near the Jubba River.[191]

Environment

Somalia is a semi-arid country with about 1.64% arable land.[1] The first local environmental organizations were Ecoterra Somalia and the Somali Ecological Society, both of which helped promote awareness about ecological concerns and mobilized environmental programs in all governmental sectors as well as in civil society. From 1971 onward, a massive tree-planting campaign on a nationwide scale was introduced by the Siad Barre government to halt the advance of thousands of acres of wind-driven sand dunes that threatened to engulf towns, roads and farm land.[194] By 1988, 265 hectares of a projected 336 hectares had been treated, with 39 range reserve sites and 36 forestry plantation sites established.[191] In 1986, the Wildlife Rescue, Research and Monitoring Centre was established by Ecoterra International, with the goal of sensitizing the public to ecological issues. This educational effort led in 1989 to the so-called "Somalia proposal" and a decision by the Somali government to adhere to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which established for the first time a worldwide ban on the trade of elephant ivory.

.jpg.webp)

Later, Fatima Jibrell, a prominent Somali environmental activist, mounted a successful campaign to conserve old-growth forests of acacia trees in the northeastern part of Somalia.[195] These trees, which can live for 500 years, were being cut down to make charcoal which was highly in demand in the Arabian Peninsula, where the region's Bedouin tribes believe the acacia to be sacred.[195][196][197] However, while being a relatively inexpensive fuel that meets a user's needs, the production of charcoal often leads to deforestation and desertification.[197] As a way of addressing this problem, Jibrell and the Horn of Africa Relief and Development Organization (Horn Relief; now Adeso), an organization of which she was the founder and executive director, trained a group of teens to educate the public on the permanent damage that producing charcoal can create. In 1999, Horn Relief coordinated a peace march in the northeastern Puntland region of Somalia to put an end to the so-called "charcoal wars". As a result of Jibrell's lobbying and education efforts, the Puntland government in 2000 prohibited the exportation of charcoal. The government has also since enforced the ban, which has reportedly led to an 80% drop in exports of the product.[198] Jibrell was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2002 for her efforts against environmental degradation and desertification.[198] In 2008, she also won the National Geographic Society/Buffett Foundation Award for Leadership in Conservation.[199]

Following the massive tsunami of December 2004, there have also emerged allegations that after the outbreak of the Somali Civil War in the late 1980s, Somalia's long, remote shoreline was used as a dump site for the disposal of toxic waste. The huge waves that battered northern Somalia after the tsunami are believed to have stirred up tons of nuclear and toxic waste that might have been dumped illegally in the country by foreign firms.[200]

The European Green Party followed up these revelations by presenting before the press and the European Parliament in Strasbourg copies of contracts signed by two European companies — the Italian Swiss firm, Achair Partners, and an Italian waste broker, Progresso — and representatives of the then President of Somalia, the faction leader Ali Mahdi Mohamed, to accept 10 million tonnes of toxic waste in exchange for $80 million (then about £60 million).[200]

According to reports by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the waste has resulted in far higher than normal cases of respiratory infections, mouth ulcers and bleeding, abdominal haemorrhages and unusual skin infections among many inhabitants of the areas around the northeastern towns of Hobyo and Benadir on the Indian Ocean coast — diseases consistent with radiation sickness. UNEP adds that the situation along the Somali coastline poses a very serious environmental hazard not only in Somalia, but also in the eastern Africa sub-region.[200]

Climate

Owing to Somalia's proximity to the equator, there is not much seasonal variation in its climate. Hot conditions prevail year-round along with periodic monsoon winds and irregular rainfall. Mean daily maximum temperatures range from 30 to 40 °C (86 to 104 °F), except at higher elevations along the eastern seaboard, where the effects of a cold offshore current can be felt. In Mogadishu, for instance, average afternoon highs range from 28 to 32 °C (82 to 90 °F) in April. Some of the highest mean annual temperatures in the world have been recorded in the country; Berbera on the northwestern coast has an afternoon high that averages more than 38 °C (100 °F) from June through September. Nationally, mean daily minimums usually vary from about 15 to 30 °C (59 to 86 °F).[191] The greatest range in climate occurs in northern Somalia, where temperatures sometimes surpass 45 °C (113 °F) in July on the littoral plains and drop below the freezing point during December in the highlands.[13][191] In this region, relative humidity ranges from about 40% in the mid-afternoon to 85% at night, changing somewhat according to the season.[191] Unlike the climates of most other countries at this latitude, conditions in Somalia range from arid in the northeastern and central regions to semiarid in the northwest and south. In the northeast, annual rainfall is less than 100 mm (4 in); in the central plateaus, it is about 200 to 300 mm (8 to 12 in). The northwestern and southwestern parts of the nation, however, receive considerably more rain, with an average of 510 to 610 mm (20 to 24 in) falling per year. Although the coastal regions are hot and humid throughout the year, the hinterland is typically dry and hot.[191]

There are four main seasons around which pastoral and agricultural life revolve, and these are dictated by shifts in the wind patterns. From December to March is the Jilal, the harshest dry season of the year. The main rainy season, referred to as the Gu, lasts from April to June. This period is characterized by the southwest monsoons, which rejuvenate the pasture land, especially the central plateau, and briefly transform the desert into lush vegetation. From July to September is the second dry season, the Xagaa (pronounced "Hagaa"). The Dayr, which is the shortest rainy season, lasts from October to December.[191] The tangambili periods that intervene between the two monsoons (October–November and March–May) are hot and humid.[191]

Wildlife

Somalia contains a variety of mammals due to its geographical and climatic diversity. Wildlife still occurring includes cheetah, lion, reticulated giraffe, baboon, serval, elephant, bushpig, gazelle, ibex, kudu, dik-dik, oribi, Somali wild ass, reedbuck and Grévy's zebra, elephant shrew, rock hyrax, golden mole and antelope. It also has a large population of the dromedary camel.[201]

Somalia is home to around 727 species of birds. Of these, eight are endemic, one has been introduced by humans, and one is rare or accidental. Fourteen species are globally threatened. Birds species found exclusively in the country include the Somali Pigeon, Alaemon hamertoni (Alaudidae), Lesser Hoopoe-Lark, Heteromirafra archeri (Alaudidae), Archer's Lark, Mirafra ashi, Ash's Bushlark, Mirafra somalica (Alaudidae), Somali Bushlark, Spizocorys obbiensis (Alaudidae), Obbia Lark, Carduelis johannis (Fringillidae), and Warsangli Linnet.[202]

Somalia's territorial waters are prime fishing grounds for highly migratory marine species, such as tuna. A narrow but productive continental shelf contains several demersal fish and crustacean species.[203] Fish species found exclusively in the nation include Cirrhitichthys randalli (Cirrhitidae), Symphurus fuscus (Cynoglossidae), Parapercis simulata OC (Pinguipedidae), Cociella somaliensis OC (Platycephalidae), and Pseudochromis melanotus (Pseudochromidae).

There are roughly 235 species of reptiles. Of these, almost half live in the northern areas. Reptiles endemic to Somalia include the Hughes' saw-scaled viper, the Southern Somali garter snake, a racer (Platyceps messanai), a diadem snake (Spalerosophis josephscorteccii), the Somali sand boa, the angled worm lizard, a spiny-tailed lizard (Uromastyx macfadyeni), Lanza's agama, a gecko (Hemidactylus granchii), the Somali semaphore gecko, and a sand lizard (Mesalina or Eremias). A colubrid snake (Aprosdoketophis andreonei) and Haacke-Greer's skink (Haackgreerius miopus) are endemic species.[204]

Politics and government

Somalia is a parliamentary representative democratic republic. The President of Somalia is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the Somali Armed Forces and selects a Prime Minister to act as head of government.[205]

The Federal Parliament of Somalia is the national parliament of Somalia. The bicameral National Legislature consists of the House of the People (lower house) and the Senate (upper house), whose members are elected to serve four-year terms. The parliament elects the President, Speaker of Parliament and Deputy Speakers. It also has the authority to pass and veto laws.[206]

The Judiciary of Somalia is defined by the Provisional Constitution of the Federal Republic of Somalia. Adopted on 1 August 2012 by a National Constitutional Assembly in Mogadishu,[207][208] the document was formulated by a committee of specialists chaired by attorney and Speaker of the Federal Parliament, Mohamed Osman Jawari.[209] It provides the legal foundation for the existence of the Federal Republic and source of legal authority.[210]

The national court structure is organized into three tiers: the Constitutional Court, Federal Government level courts and State level courts. A nine-member Judicial Service Commission appoints any Federal tier member of the judiciary. It also selects and presents potential Constitutional Court judges to the House of the People of the Federal Parliament for approval. If endorsed, the President appoints the candidate as a judge of the Constitutional Court. The five-member Constitutional Court adjudicates issues pertaining to the constitution, in addition to various Federal and sub-national matters.[210]

Somali law draws from a mixture of three different systems: civil law, Islamic law and customary law.[211]

According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices Somalia is 5th least democratic country in Africa.[212]

After the collapse of Somalia in 1991, there were no relations or any contact between the Somaliland government, which declared itself a country, and the government of Somalia.[213][214]

Foreign relations

.jpg.webp)

Somalia's foreign relations are handled by the President as the head of state, the Prime Minister as the head of government, and the federal Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[210]

According to Article 54 of the national constitution, the allocation of powers and resources between the Federal Government and the Federal Republic of Somalia's constituent Federal Member States shall be negotiated and agreed upon by the Federal Government and the Federal Member States, except in matters pertaining to foreign affairs, national defence, citizenship and immigration, and monetary policy. Article 53 also stipulates that the Federal Government shall consult the Federal Member States on major issues related to international agreements, including negotiations vis-a-vis foreign trade, finance and treaties.[210] The Federal Government maintains bilateral relations with a number of other central governments in the international community. Among these are Djibouti, Ethiopia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Turkey, Italy, the United Kingdom, Denmark, France, the United States, the People's Republic of China, Japan, Russian Federation and South Korea.

Additionally, Somalia has several diplomatic missions abroad. There are likewise various foreign embassies and consulates based in the capital Mogadishu and elsewhere in the country.

Somalia is also a member of many international organizations, such as the United Nations, African Union and Arab League. It was a founding member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in 1969.[215] Other memberships include the African Development Bank, East African Community, Group of 77, Intergovernmental Authority on Development, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, International Civil Aviation Organization, International Development Association, International Finance Corporation, Non-Aligned Movement, World Federation of Trade Unions and World Meteorological Organization.

Military

.jpg.webp)

The Somali Armed Forces (SAF) are the military forces of the Federal Republic of Somalia.[216] Headed by the President as Commander in Chief, they are constitutionally mandated to ensure the nation's sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity.[210]

The SAF was initially made up of the Army, Navy, Air Force, Police Force and the National Security Service.[217] In the post-independence period, it grew to become among the larger militaries on the continent.[146] The subsequent outbreak of the civil war in 1991 led to the disbandment of the Somali National Army.[218]

In 2004, the gradual process of reconstituting the military was put in motion with the establishment of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG). The Somali Armed Forces are now overseen by the Ministry of Defence of the Federal Government of Somalia, formed in mid-2012. In January 2013, the Somali federal government also re-opened the national intelligence service in Mogadishu, renaming the agency the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA).[219] The Somaliland and Puntland regional governments maintain their own security and police forces.

Human rights

Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are punishable by death within Somalia.[220]

On October 3, 2020, a UN human rights investigator raised concerns over Somali government's backtracking of human rights commitments. According to information collected by the investigator, Somali authorities were regressing on commitments to protect peoples' economic, social and cultural rights.[221]

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

According to the CIA and the Central Bank of Somalia, despite experiencing civil unrest, Somalia has maintained a healthy informal economy, based mainly on livestock, remittance/money transfer companies and telecommunications.[1][51] Owing to a dearth of formal government statistics and the recent civil war, it is difficult to gauge the size or growth of the economy. For 1994, the CIA estimated the GDP at $3.3 billion.[222] In 2001, it was estimated to be $4.1 billion.[223] By 2009, the CIA estimated that the GDP had grown to $5.731 billion, with a projected real growth rate of 2.6%.[1] According to a 2007 British Chambers of Commerce report, the private sector also grew, particularly in the service sector. Unlike the pre-civil war period when most services and the industrial sector were government-run, there has been substantial, albeit unmeasured, private investment in commercial activities; this has been largely financed by the Somali diaspora, and includes trade and marketing, money transfer services, transportation, communications, fishery equipment, airlines, telecommunications, education, health, construction and hotels.[224] Libertarian economist Peter Leeson attributes this increased economic activity to the Somali customary law (referred to as Xeer), which he suggests provides a stable environment to conduct business in.[225]

.jpg.webp)

According to the Central Bank of Somalia, the country's GDP per capita as of 2012 is $226, a slight reduction in real terms from 1990.[226] About 43% of the population lives on less than 1 US dollar a day, with around 24% of those found in urban areas and 54% living in rural areas.[51]

Somalia's economy consists of both traditional and modern production, with a gradual shift toward modern industrial techniques. Somalia has the largest population of camels in the world.[227] According to the Central Bank of Somalia, about 80% of the population are nomadic or semi-nomadic pastoralists, who keep goats, sheep, camels and cattle. The nomads also gather resins and gums to supplement their income.[51]

Agriculture

Agriculture is the most important economic sector of Somalia. It accounts for about 65% of the GDP and employs 65% of the workforce.[224] Livestock contributes about 40% to GDP and more than 50% of export earnings.[1] Other principal exports include fish, charcoal and bananas; sugar, sorghum and corn are products for the domestic market.[1] According to the Central Bank of Somalia, imports of goods total about $460 million per year, surpassing aggregate imports prior to the start of the civil war in 1991. Exports, which total about $270 million annually, have also surpassed pre-war aggregate export levels. Somalia has a trade deficit of about $190 million per year, but this is exceeded by remittances sent by Somalis in the diaspora, estimated to be about $1 billion.[51]

With the advantage of being located near the Arabian Peninsula, Somali traders have increasingly begun to challenge Australia's traditional dominance over the Gulf Arab livestock and meat market, offering quality animals at very low prices. In response, Gulf Arab states have started to make strategic investments in the country, with Saudi Arabia building livestock export infrastructure and the United Arab Emirates purchasing large farmlands.[228] Somalia is also a major world supplier of frankincense and myrrh.[229]

The modest industrial sector, based on the processing of agricultural products, accounts for 10% of Somalia's GDP.[1] According to the Somali Chamber of Commerce and Industry, over six private airline firms also offer commercial flights to both domestic and international locations, including Daallo Airlines, Jubba Airways, African Express Airways, East Africa 540, Central Air and Hajara.[230] In 2008, the Puntland government signed a multimillion-dollar deal with Dubai's Lootah Group, a regional industrial group operating in the Middle East and Africa. According to the agreement, the first phase of the investment is worth Dhs 170 m and will see a set of new companies established to operate, manage and build Bosaso's free trade zone and sea and airport facilities. The Bosaso Airport Company is slated to develop the airport complex to meet international standards, including a new 3,400 m (11,200 ft) runway, main and auxiliary buildings, taxi and apron areas, and security perimeters.[231]

Prior to the outbreak of the civil war in 1991, the roughly 53 state-owned small, medium and large manufacturing firms were foundering, with the ensuing conflict destroying many of the remaining industries. However, primarily as a result of substantial local investment by the Somali diaspora, many of these small-scale plants have re-opened and newer ones have been created. The latter include fish-canning and meat-processing plants in the northern regions, as well as about 25 factories in the Mogadishu area, which manufacture pasta, mineral water, confections, plastic bags, fabric, hides and skins, detergent and soap, aluminium, foam mattresses and pillows, fishing boats, carry out packaging, and stone processing.[232] In 2004, an $8.3 million Coca-Cola bottling plant also opened in the city, with investors hailing from various constituencies in Somalia.[233] Foreign investment also included multinationals including General Motors and Dole Fruit.[234]

Monetary and payment system

The Central Bank of Somalia is the official monetary authority of Somalia.[51] In terms of financial management, it is in the process of assuming the task of both formulating and implementing monetary policy.[235]

Owing to a lack of confidence in the local currency, the US dollar is widely accepted as a medium of exchange alongside the Somali shilling. Dollarization notwithstanding, the large issuance of the Somali shilling has increasingly fuelled price hikes, especially for low value transactions. According to the Central Bank, this inflationary environment is expected to come to an end as soon as the bank assumes full control of monetary policy and replaces the presently circulating currency introduced by the private sector.[235]

Although Somalia has had no central monetary authority for more than 15 years between the outbreak of the civil war in 1991 and the subsequent re-establishment of the Central Bank of Somalia in 2009, the nation's payment system is fairly advanced primarily due to the widespread existence of private money transfer operators (MTO) that have acted as informal banking networks.[236]

These remittance firms (hawalas) have become a large industry in Somalia, with an estimated US$1.6 billion annually remitted to the region by Somalis in the diaspora via money transfer companies.[1] Most are members of the Somali Money Transfer Association (SOMTA), an umbrella organization that regulates the community's money transfer sector, or its predecessor, the Somali Financial Services Association (SFSA).[237][238] The largest of the Somali MTOs is Dahabshiil, a Somali-owned firm employing more than 2,000 people across 144 countries with branches in London and Dubai.[238]

As the reconstituted Central Bank of Somalia fully assumes its monetary policy responsibilities, some of the existing money transfer companies are expected in the near future to seek licenses so as to develop into full-fledged commercial banks. This will serve to expand the national payments system to include formal cheques, which in turn is expected to reinforce the efficacy of the use of monetary policy in domestic macroeconomic management.[236]

With a significant improvement in local security, Somali expatriates began returning to the country for investment opportunities. Coupled with modest foreign investment, the inflow of funds have helped the Somali shilling increase considerably in value. By March 2014, the currency had appreciated by almost 60% against the U.S. dollar over the previous 12 months. The Somali shilling was the strongest among the 175 global currencies traded by Bloomberg, rising close to 50 percentage points higher than the next most robust global currency over the same period.[239]

The Somalia Stock Exchange (SSE) is the national bourse of Somalia. It was founded in 2012 by the Somali diplomat Idd Mohamed, Ambassador extraordinary and deputy permanent representative to the United Nations. The SSE was established to attract investment from both Somali-owned firms and global companies in order to accelerate the ongoing post-conflict reconstruction process in Somalia.[240]

Energy and natural resources

The World Bank reports that electricity is now in large part supplied by local businesses.[224] Among these domestic firms is the Somali Energy Company, which performs generation, transmission and distribution of electric power.[241] In 2010, the nation produced 310 million kWh and consumed 288.3 million kWh of electricity, ranked 170th and 177th, respectively, according to the CIA.[1]

Somalia has reserves of several natural resources, including uranium, iron ore, tin, gypsum, bauxite, copper, salt and natural gas. The CIA reports that there are 5.663 billion cubic metres of proven natural gas reserves.[1]

The presence or extent of proven oil reserves in Somalia is uncertain. The CIA asserts that as of 2011 there are no proven reserves of oil in the country,[1] while UNCTAD suggests that most proven oil reserves in Somalia lie off its northwestern coast, in the Somaliland region.[242] An oil group listed in Sydney, Range Resources, estimates that the Puntland region in the northeast has the potential to produce 5 billion barrels (790×106 m3) to 10 billion barrels (1.6×109 m3) of oil,[243] compared to the 6.7 billion barrels of proven oil reserves in Sudan.[244] As a result of these developments, the Somalia Petroleum Corporation was established by the federal government.[245]

In the late 1960s, UN geologists also discovered major uranium deposits and other rare mineral reserves in Somalia. The find was the largest of its kind, with industry experts estimating that the amount of the deposits could amount to over 25% of the world's then known uranium reserves of 800,000 tons.[246] In 1984, the IUREP Orientation Phase Mission to Somalia reported that the country had 5,000 tons of uranium reasonably assured resources (RAR), 11,000 tons of uranium estimated additional resources (EAR) in calcrete deposits, as well as 0–150,000 tons of uranium speculative resources (SR) in sandstone and calcrete deposits.[247] Somalia evolved into a major world supplier of uranium, with American, UAE, Italian and Brazilian mineral companies vying for extraction rights. Link Natural Resources has a stake in the central region, and Kilimanjaro Capital has a stake in the 1,161,400 acres (470,002 ha) Amsas-Coriole-Afgoi (ACA) Block, which includes uranium exploration.[248]

The Trans-National Industrial Electricity and Gas Company is an energy conglomerate based in Mogadishu. It unites five major Somali companies from the trade, finance, security and telecommunications sectors, following a 2010 joint agreement signed in Istanbul to provide electricity and gas infrastructure in Somalia. With an initial investment budget of $1 billion, the company launched the Somalia Peace Dividend Project, a labour-intensive energy program aimed at facilitating local industrialization initiatives.

According to the Central Bank of Somalia, as the nation embarks on the path of reconstruction, the economy is expected to not only match its pre-civil war levels, but also to accelerate in growth and development due to Somalia's untapped natural resources.[51]

Telecommunications and media

After the start of the civil war, various new telecommunications companies began to spring up and compete to provide missing infrastructure. Funded by Somali entrepreneurs and backed by expertise from China, South Korea and Europe, these nascent telecommunications firms offer affordable mobile phone and Internet services that are not available in many other parts of the continent. Customers can conduct money transfers (such as through the popular Dahabshiil) and other banking activities via mobile phones, as well as easily gain wireless Internet access.[249]

After forming partnerships with multinational corporations such as Sprint, ITT and Telenor, these firms now offer the cheapest and clearest phone calls in Africa.[250] These Somali telecommunication companies also provide services to every city and town in Somalia. There are presently around 25 mainlines per 1,000 persons, and the local availability of telephone lines (tele-density) is higher than in neighbouring countries; three times greater than in adjacent Ethiopia.[232] Prominent Somali telecommunications companies include Golis Telecom Group, Hormuud Telecom, Somafone, Nationlink, Netco, Telcom and Somali Telecom Group. Hormuud Telecom alone grosses about $40 million a year. Despite their rivalry, several of these companies signed an inter-connectivity deal in 2005 that allows them to set prices, maintain and expand their networks, and ensure that competition does not get out of control.[249]

Investment in the telecom industry is held to be one of the clearest signs that Somalia's economy has continued to develop despite civil strife in parts of the country.[249]

The state-run Somali National Television is the principal national public service TV channel. After a twenty-year hiatus, the station was officially re-launched on 4 April 2011.[251] Its radio counterpart Radio Mogadishu also broadcasts from the capital. Somaliland National TV and Puntland TV and Radio air from the northern regions.

Additionally, Somalia has several private television and radio networks. Among these are Horn Cable Television and Universal TV.[1] The political Xog Doon and Xog Ogaal and Horyaal Sports broadsheets publish out of the capital. There are also a number of online media outlets covering local news,[252] including Garowe Online, Wardheernews, and Puntland Post.

The internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Somalia is .so. It was officially relaunched on 1 November 2010 by .SO Registry, which is regulated by the nation's Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications.[253]

On 22 March 2012, the Somali Cabinet also unanimously approved the National Communications Act. The bill paves the way for the establishment of a National Communications regulator in the broadcasting and telecommunications sectors.[254]

In November 2013, following a Memorandum of Understanding signed with Emirates Post in April of the year, the federal Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications officially reconstituted the Somali Postal Service (Somali Post).[255] In October 2014, the ministry also relaunched postal delivery from abroad.[256] The postal system is slated to be implemented in each of the country's 18 administrative provinces via a new postal coding and numbering system.[257]

Tourism

Somalia has a number of local attractions, consisting of historical sites, beaches, waterfalls, mountain ranges and national parks. The tourist industry is regulated by the national Ministry of Tourism. The autonomous Puntland and Somaliland regions maintain their own tourism offices.[258] The Somali Tourism Association (SOMTA) also provides consulting services from within the country on the national tourist industry.[259] As of March 2015, the Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife of the South West State announced that it is slated to establish additional game reserves and wildlife ranges.[260] The United States Government recommends travelers to not travel to Somalia.[261]

Notable sights include the Laas Geel caves containing Neolithic rock art; the Cal Madow, Golis Mountains and Ogo Mountains; the Iskushuban and Lamadaya waterfalls; and the Hargeisa National Park, Jilib National Park, Kismayo National Park and Lag Badana National Park.

Transport

Somalia's network of roads is 22,100 km (13,700 mi) long. As of 2000, 2,608 km (1,621 mi) streets are paved and 19,492 km (12,112 mi) are unpaved.[1] A 750 km (470 mi) highway connects major cities in the northern part of the country, such as Bosaso, Galkayo and Garowe, with towns in the south.[262]