Shōka (唱歌) or Monbushō shōka (文部省唱歌) is a genre of Japanese song, commonly taught and sung in the public schools. Shōka also refers to one subject in the former elementary schools of Japan.

History

In 1872, the Meiji government promulgated the first educational constitution called Gakusei (学生) and set up shōka (唱歌) as a subject in elementary schools.[1] However, the subject was not taught due to the lack of teaching materials.

Japanese court musicians composed most of the music for kindergarten, such they were the only musicians with knowledge in Japanese and Western music. In 1878, they composed Kazaguruma (Windfans), commissioned by the Tokyo Women's Teacher College.[1]

In 1879, the government established Ongaku Torishirabe Gakari (Musical Investigation Committee), which decided about music teaching in the public schools.[1] The first principal of the Ongaku Torishirabe Gakari, Isawa Shūji, proposed to mix Western and Eastern music to create new national music.[1] The Musical Investigation Committee investigated the history and theories of several kinds of music around the world. In the first report of the committee, Izawa concluded that Western and Oriental music was similar.[1]

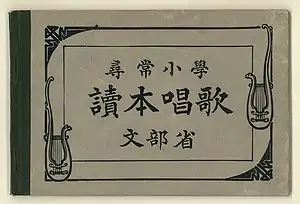

In 1881, the first official shōka songbook (Shōgaku-shōka-shū) was published.[2] This book was mainly a collection of Western folk music tunes with Japanese lyrics and was developed with the collaboration between Japanese educator Isawa Shūji, American music educationist Luther Whiting Mason, and a team of language experts.[1][2] The songbook recorded 33 songs in its first edition. However, only three of them were original compositions, with two composed by the court musician Fujitsune Shiba. The rest of the songs were chosen by Mason's National Music Course and other American music textbooks.[1]

In 1888, the first privately published collections of shōka songs circulated in Japan. The Ministry of Education in Japan realized that western songbooks were useful for unifying and integrating citizens of a nation.[2]

In 1890, Musical Investigation Committee changed its name to Tokyo Music School and hired German musicians, and stopped teaching Japanese music. However, music textbooks that mixed Western melodies with Japanese text for school appeared after Shogaku Shokashu.[1]

In 1893, the Ministry of Education selected eight shōka songbooks for Imperial Holidays. In this book, songs with traditional Japanese Pentatonic scale were preferred, instead of the western diatonic scale. In this way, shōka songs sounded more familiar to Japanese people and got more popularity.[2]

Characteristics

Composers used to choose an appropriate text and then compose the melody, written in Western notation but with the tonality of the Ritsu scales used in Gagaku. Gagaku music was the model for shōka as it was considered noble and harmless.[1]

In the songs for the public schools, Japanese instruments such as koto and kokyū were relegated and Western instruments such as piano and organ were preferred. However, some songbooks included tunes in Japanese scales and songs for shamisen.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ogawa, Masafumi (1994). "Japanese Traditional Music and School Music Education". Philosophy of Music Education Review. 2 (1): 25–36. ISSN 1063-5734. JSTOR 40327067. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Van der Does-Ishikawa, Luli (2013). A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Japanese Children's Official Songbooks, 1881-1945: Nurturing an Imperial Ideology Through the Manipulation of Language. University of Sheffield. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ↑ Signell, Karl (1976). "The Modernization Process in Two Oriental Music Cultures: Turkish and Japanese". Asian Music. 7 (2): 72–102. doi:10.2307/833790. JSTOR 833790.