| Seleucus VI Epiphanes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

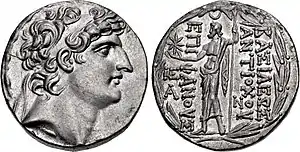

Seleucus VI's portrait on the obverse of a tetradrachm minted in Antioch | |||||

| King of Syria | |||||

| Reign | 96–94 BC | ||||

| Predecessor | Antiochus VIII, Antiochus IX | ||||

| Successor | Demetrius III, Antiochus X, Antiochus XI, Philip I | ||||

| Died | 94 BC Mopsuestia in Cilicia (modern-day Yakapınar, Yüreğir, Adana, Turkey) | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Seleucid | ||||

| Father | Antiochus VIII | ||||

| Mother | Tryphaena | ||||

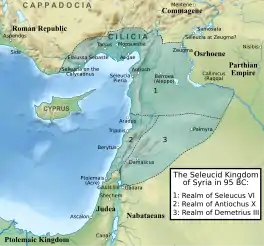

Seleucus VI Epiphanes Nicator (Ancient Greek: Σέλευκος Ἐπιφανής Νικάτωρ, romanized: Séleukos Epiphanís Nikátor; between 124 and 109 BC – 94 BC) was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who ruled Syria between 96 and 94 BC. He was the son of Antiochus VIII and his Ptolemaic Egyptian wife Tryphaena. Seleucus VI lived during a period of civil war between his father and his uncle Antiochus IX, which ended in 96 BC when Antiochus VIII was assassinated. Antiochus IX then occupied the capital Antioch while Seleucus VI established his power-base in western Cilicia and himself prepared for war. In 95 BC, Antiochus IX marched against his nephew, but lost the battle and was killed. Seleucus VI became the master of the capital but had to share Syria with his brother Demetrius III, based in Damascus, and his cousin, Antiochus IX's son Antiochus X.

According to the ancient historian Appian, Seleucus VI was a violent ruler. He taxed his dominions extensively to support his wars, and resisted allowing the cities a measure of autonomy, as had been the practice of former kings. His reign did not last long; in 94 BC, he was expelled from Antioch by Antiochus X, who followed him to the Cilician city of Mopsuestia. Seleucus took shelter in the city where his attempts to raise money led to riots that eventually claimed his life in 94 BC. Ancient traditions have different versions of his death, but he was most probably burned alive by the rioters. Following his demise, his brothers Antiochus XI and Philip I destroyed Mopsuestia as an act of revenge and their armies fought those of Antiochus X.

Name, family and early life

"Seleucus" was a dynastic name in the Seleucid dynasty,[note 1][2][3] and it is the Macedonian variant of the Greek Ζάλευκος (zaleucus), meaning 'the shining white'.[note 2][7][8] Antiochus VIII married the Ptolemaic Egyptian princess Tryphaena in c. 124 BC,[9] shortly after his ascension to the throne; Seleucus VI was the couple's eldest son.[note 3][11] From 113 BC, Antiochus VIII had to contend with his half-brother Antiochus IX for the throne. The civil war continued for more than a decade;[12] it claimed the life of Tryphaena in 109 BC,[13] and ended when Antiochus VIII was assassinated in 96 BC.[14] In the aftermath of his brother's murder, Antiochus IX advanced on the capital Antioch and took it; he also married the second wife and widow of Antiochus VIII, Cleopatra Selene.[15] According to an inscription, the city of Priene sent honors to "Seleucus son of King Antiochus son of King Demetrius"; the embassy probably took place before Seleucus VI ascended the throne as the inscription does not mention him as a king.[16] The embassy of Priene probably met Seleucus VI in Cilicia; Antiochus VIII might have sent his son to that region as a strategos.[17]

Reign

Following his father's death, Seleucus VI declared himself king and took the city of Seleucia on the Calycadnus in western Cilicia as his base,[18][19] while his brother Demetrius III took Damascus.[20] The volume of coins minted by the new king in Seleucia on the Calycadnus surpassed any other mint known from the late Seleucid period, and most of the coins were produced during his preparations for war against Antiochus IX,[note 4][23] a conflict that would end in the year 96/95 BC (217 SE (Seleucid year)).[note 5][17] This led the numismatist Arthur Houghton to suggest an earlier death for Antiochus VIII and a longer reign for Seleucus VI beginning in 98 or 97 BC instead of 96 BC.[19] The numismatist Oliver D. Hoover contested Houghton's hypothesis, as it was not rare for a king to double his production in a single year at times of need,[25] and the academic consensus prefers the year 96 BC for the death of Antiochus VIII.[26]

Titles and royal image

Ancient Hellenistic kings did not use regnal numbers. Instead, they employed epithets to distinguish themselves from other kings with similar names; the numbering of kings is a modern practice.[27][28] Seleucus VI appeared on his coins with the epithets Epiphanes (God Manifest) and Nicator (Victorious).[note 6][21] As being the son of Antiochus VIII was the source of his legitimacy as king, Seleucus VI sought to emphasize his descent by depicting himself on the coinage with an exaggerated hawk-nose in the likeness of his father.[32]

Another iconographic element of Seleucus VI's coinage is the short vertical stubby horns above the temple area; the meaning of this motif has been debated among scholars. It is likely an allusion to Seleucus VI's descent from his grandfather Demetrius II, who utilized the same motif. The specific meaning of the horns is not clear, but it could have been an indication that the king was a manifestation of a god;[33] the stubby horns sported by Seleucus VI probably carried the same meaning as those of his grandfather.[note 7][36] In the Seleucid dynasty, currency struck during campaigns against a rival (or usurper) showed the king with a beard.[37] Seleucus VI was depicted with a beard, which was later removed from coins, indicating the fulfilment of a vengeance vow to avenge his father.[36]

Struggle against Antiochus IX

In Seleucia on the Calycadnus, Seleucus VI prepared for war against his uncle, whose forces probably occupied central Cilicia and confined his nephew to the western parts of the region.[19] The king needed a harbor for Seleucia on the Calycadnus and probably founded the city of Elaiussa to serve that purpose.[note 8][41] Seleucus VI gathered funds for his coming war from the cities of Cilicia, including Mopsuestia, which seems to have been taxed on several occasions.[42] During his reign, it is estimated that Seleucus VI produced 1,200 talents of coins to support his war effort, enough to pay ten thousand soldiers for two years.[43] On the reverse of bronze coins produced in a mint whose location is not known, coded uncertain mint 125, a motif depicting a chelys formed in the shape of a Macedonian shield appeared on the reverse. This motif was probably meant to rally the support of military Macedonian colonists in the region.[36] Those coins were probably produced in Syria, in a city half the way between Tarsus in Cilicia and Antioch; therefore, they were probably minted in the course of Seleucus VI's campaign against Antiochus IX.[44]

Antiochus IX took note of Seleucus VI's preparations; after the latter started his march on Antioch in 95 BC,[45] Antiochus IX left the capital and moved against his nephew. Seleucus VI emerged victorious while his uncle lost his life, either by committing suicide according to the 3rd-century historian Eusebius, or by being executed according to the 1st-century historian Josephus.[46] Soon afterwards, Seleucus VI entered the capital; Cleopatra Selene probably fled before his arrival.[17]

Policy and the war against Antiochus X

In 144 SE (169/168 BC), King Antiochus IV allowed nineteen cities to mint municipal bronze coinage in their own names, indicating his awareness of the mutual dependency of cities and the monarchy on each other.[note 9][47] This movement towards greater autonomy continued as the cities sought to emancipate themselves from the central power, adding the phrase "sacred and autonomous" to their coinage.[50] Seleucus VI did not follow the policy of his forebears. In Cilicia, as long as he reigned, autonomy was not granted; a change in the political status of Cilician cities was apparently not acceptable for Seleucus VI.[51]

Seleucus VI controlled Cilicia and Syria Seleucis (Northern Syria).[note 10][40] Antiochus IX had a son, Antiochus X; according to Josephus, he fled to the city of Aradus where he declared himself king.[57] Seleucus VI attempted to kill his cousin and rival but the plot failed,[58] and Antiochus X married Cleopatra Selene to enhance his position.[59] The archaeologist Alfred Bellinger believed that Seleucus VI prepared for his coming war against Antiochus X in Elaiussa.[40] In 94 BC, Antiochus X advanced on the capital Antioch and drove Seleucus VI out of northern Syria into Cilicia.[26] According to Eusebius, the final battle took place near Mopsuestia, and ended with the defeat of Seleucus VI.[60]

Death and legacy

Described by the 2nd-century historian Appian as "violent and extremely tyrannical",[61] Seleucus VI took shelter in Mopsuestia,[62] and attempted to tax the residents again, which led to his death during riots.[63][64] The year of his demise is not clear; Eusebius placed it in 216 SE (97/96 BC), which is impossible considering that a market weight of Seleucus VI from Antioch dated to 218 SE (95/94 BC) has been discovered. The 4th-century historian Jerome has 219 SE (94/93 BC) as the year of Seleucus VI's demise, which is more plausible.[65] The year 94 BC is the academically accepted date for the death of Seleucus VI.[66] No spouse or children were recorded for Seleucus VI.[67] According to the 1st-century biographer Plutarch, the 1st-century BC Roman general Lucullus said that the Armenian king, Tigranes II, who conquered Syria in 83 BC, "put to death the successors of Seleucus, and [carried] off their wives and daughters into captivity". Given the fragmentary nature of ancient sources regarding the late Seleucid period, the statement of Lucullus leaves open the existence of a wife or daughter of Seleucus VI.[68]

Ancient traditions preserve three accounts regarding Seleucus VI's death: the oldest, by Josephus, has a mob burning the king and his courtiers in the royal palace. Appian shares the burning account but has the city's gymnasium as the scene. According to Eusebius, Seleucus VI discovered the intention of the residents to burn him, and took his own life. Bellinger considered the account of Josephus to be the most probable; he noted that Eusebius presented suicide accounts for other Seleucid kings who were recorded as having been killed by other historians, such as Alexander I and Antiochus IX. Bellinger believed that the 3rd-century historian Porphyry, the source of Eusebius' stories about the Seleucids, was attempting to "tone down somewhat the horrors of the Seleucid house".[69]

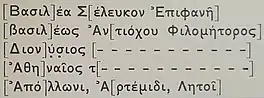

The city of Athens shared a close relation with the Seleucid kings, and statues of Syrian monarchs set up by Athenian citizens on the island of Delos testify to this;[70] a citizen named Dionysius dedicated a statue for Seleucus VI between 96 and 94 BC.[note 11][73][74] In deference to his late brother, King Antiochus XI adopted the epithet Philadelphus (brother loving).[75] Along with his twin Philip I, Antiochus XI proceeded to avenge Seleucus VI; the brothers sacked and destroyed Mopsuestia.[76] Antiochus XI then headed to Antioch in 93 BC and expelled Antiochus X.[77]

Family tree

| Family tree of Seleucus VI |

|---|

Citations:

|

See also

Notes

- ↑ In Greek:

English translation:[Βασιλ]έα Σ[έλευκον Ἐπιφανῆ]

[βασιλ]έως Ἀν[τιόχου Φιλομήτορος]

[Διον]ύσιος [...]

[Ἀθη]ναῖος τ[...]

[Ἀπό]λλωνι, Ἀ[ρτέμιδι, Λητοῖ].(implied: Dedicated to the) King S[eleukos Epiphanes],

(son) of king An[tiochos Philometor],

[Dion]ysios [...]

the [Athe]nian [...]

to [Apo]llo, A[rtemis, Leto].

- ↑ It was customary to name the eldest son after the dynasty's founder Seleucus I, while a younger son would be named Antiochus.[1]

- ↑ The linguist Radoslav Katičić considered it comparable to λευχός, meaning 'white'.[4] The name Zaleucus is etymologically related to brightness. The historian Frank Adcock agreed with the linguist Otto Hoffmann who considered Seleucus and Zaleucus different pronunciations of the same name.[5][6]

- ↑ Ancient sources do not mention the name of Seleucus VI's mother but it is generally assumed by modern scholars that she was Tryphaena, who was mentioned explicitly by Porphyry as the mother of Seleucus VI's younger brothers Antiochus XI and Philip I.[10]

- ↑ Historian Henry Noel Humphreys considered the coins of Seleucus VI to be the beginning of decadence in Syro-Greek art.[21] The coins minted at Seleucia on the Calycadnus were also reduced 0.5 g (0.018 oz) in weight compared to the coins minted during the reigns of Antiochus VIII and Antiochus IX in Antioch.[22]

- ↑ Some dates in the article are given according to the Seleucid era. Each Seleucid year started in the late autumn of a Gregorian year; thus, a Seleucid year overlaps two Gregorian ones.[24]

- ↑ The author of 4 Maccabees mentions a king called "Seleucus Nicanor", but no Seleucid king is known to have borne this epithet. The academic consensus considers this to be a historical error on the side of the author.[29] Historian Matthijs den Dulk suggested that this was not a mistake; all Greek manuscripts of 4 Maccabees, aside from one, have "Nicanor", but the Syriac manuscripts have "Nicator". Despite Nicator being the official rendering used by the only two kings who bore the epithet, Seleucus I and Seleucus VI, "Nicanor" was also used by ancient historians, such as Polybius, Josephus and Porphyry, in reference to Seleucus I.[30] Historian Jan Willem van Henten suggested that the intended king was Seleucus VI rather than Seleucus I. Den Dulk rejected this hypothesis because the author of 4 Maccabees mentioned that "Seleucus Nicanor" reigned before the time of the Jewish high priest Onias III, who is separated from Seleucus VI by almost a century. This makes the identification of "Seleucus Nicanor" with Seleucus VI difficult.[31]

- ↑ In the case of Demetrius II, different scholars suggested several interpretations. Roland Smith and Robert Fleischer suggested that it indicated the god Dionysus Taureos. Niklaus Dürr suggested that the horns represented a heifer, and was meant to represent Io. Thomas Fischer and Kay Ehling considered it a possible allusion to Seleucus I, the founder of the dynasty.[34] Hoover and Arthur Houghton considered it a sign of divine attributes, utilized by Demetrius II following the example of his ancestors, such as Seleucus I, Seleucus II and Antiochus III.[35]

- ↑ The earliest Seleucid coins attributed to Elaiussa were struck by Seleucus VI.[38] The archaeologist Alfred Bellinger attributed rare issues of Antiochus VIII to Elaiussa, but this has not been widely accepted by scholars.[39][40] The earliest mention of the name "Elaiussa" comes from coins autonomously issued by the city after the demise of Seleucus VI.[38]

- ↑ Antiochus IV needed the cities' loyalty, and thus, conferred the prerogative on them.[47] Minting coinage was a sign of autonomy, derived from the tradition of Greek poleis (i.e. city states).[48] The autonomy of Seleucid cities did not affect the cities' obligations towards the king so long as the monarchy was strong, but when the center became weaker, during the era of Antiochus VIII and Antiochus IX, the cities acquired traditional powers of Greek poleis.[49]

- ↑ Regarding the geographical extent of Seleucus VI's dominions:

- The Romans established a province of Cilicia in 102 BC, but it did not include areas geographically in the region, and the city of Side was the easternmost point of that province.[52]

- The Italian numismatist Nicola Francesco Haym, based on a coin of Seleucus VI, proposed that the king's realm extended beyond the Euphrates river to the Tigris, and that he held court in the city of Nisibis. Haym reached his conclusion by reading the monogram on the coin, which he thought represented the city of Nisibis.[53] This coin was minted in Seleucia on the Calycadnus according to modern numismatists, such as Houghton.[54] Following the defeat of Antiochus VII (died 129 BC) in his war against Parthia, the Euphrates became Syria's eastern border.[55] Parthia established the river as its western border and included the region of Osroene.[56]

- ↑ The inscription is damaged; it was reconstructed by Théophile Homolle,[71] then by Pierre Roussel, who read the damaged king's name as "Seleucus".[72] Homolle identified the king as Seleucus VI and this identification has been accepted by many scholars, including Roussel.[71]

References

Citations

- ↑ Taylor 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ Bevan 2014, p. 56.

- ↑ Hoover 1998, p. 81.

- ↑ Katičić 1976, p. 113.

- ↑ Adcock 1927, p. 97.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1906, p. 174.

- ↑ Libanius 1992, p. 111.

- ↑ Ogden 2017, p. 11.

- ↑ Otto & Bengtson 1938, pp. 103, 104.

- ↑ Bennett 2002, p. note 7.

- ↑ Ogden 1999, pp. 153, 156.

- ↑ Kosmin 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Wright 2012, pp. 11.

- ↑ Ogden 1999, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Dumitru 2016, pp. 260–261.

- ↑ Sumner 1978, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 Dumitru 2016, p. 262.

- ↑ Josephus 1833, p. 420.

- 1 2 3 Houghton 1989, p. 98.

- ↑ Houghton & Müseler 1990, p. 61.

- 1 2 Humphreys 1853, p. 134.

- ↑ Houghton 1992, p. 133.

- ↑ Houghton 1989, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Biers 1992, p. 13.

- ↑ Hoover 2007, p. 286.

- 1 2 Houghton 1989, p. 97.

- ↑ McGing 2010, p. 247.

- ↑ Hallo 1996, p. 142.

- ↑ Den Dulk 2014, p. 133.

- ↑ Den Dulk 2014, p. 134.

- ↑ Den Dulk 2014, p. 135.

- ↑ Wright 2011, p. 46.

- ↑ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 562.

- ↑ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 411.

- ↑ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 412.

- 1 2 3 Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 552.

- ↑ Lorber & Iossif 2009, p. 112.

- 1 2 Equini Schneider 1999b, p. 34.

- ↑ Houghton & Moore 1988, pp. 67–68.

- 1 2 3 Houghton 1989, p. 78.

- ↑ Tempesta 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Bellinger 1949, p. 73.

- ↑ Aperghis 2004, p. 239.

- ↑ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 560.

- ↑ Downey 2015, p. 133.

- ↑ Bellinger 1949, pp. 72–73.

- 1 2 Meyer 2001, p. 506.

- ↑ Howgego 1995, pp. 41, 43.

- ↑ Bar-Kochva 1976, p. 219.

- ↑ Equini Schneider 1999a, p. 380.

- ↑ Houghton & Bendall 1988, p. 85.

- ↑ Oktan 2011, pp. 268, 273.

- ↑ Haym 1719, p. 42.

- ↑ Houghton 1989, p. 93.

- ↑ Hogg 1911, p. 184.

- ↑ Kia 2016, p. 55.

- ↑ Josephus 1833, p. 421.

- ↑ Appian 1899, p. 324.

- ↑ Dumitru 2016, p. 264.

- ↑ Eusebius 1875, p. 259.

- ↑ Langer 1994, p. 244.

- ↑ Ogden 1999, p. 154.

- ↑ Houghton 1998, p. 66.

- ↑ Bellinger 1949, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Hoover 2007, p. 289.

- ↑ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 551; Houghton 1987, p. 79; Lorber & Iossif 2009, pp. 102–103; Roussel & Launey 1937, p. 47; Habicht 2006, p. 172; Wright 2011, p. 42.

- ↑ Ogden 1999, p. 156.

- ↑ Dumitru 2016, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Bellinger 1949, p. 74.

- ↑ Habicht 2006, p. 171.

- 1 2 Roussel & Launey 1937, p. 47.

- ↑ Roussel 1916, p. 67.

- ↑ Habicht 2006, p. 172.

- ↑ Grainger 1997, p. 65.

- ↑ Coloru 2015, p. 177.

- ↑ Houghton 1987, p. 79.

- ↑ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 573.

Sources

- Adcock, Frank Ezra (1927). "Literary Tradition and Early Greek Code-Makers". The Cambridge Historical Journal. Cambridge University Press. 2 (2): 95–109. doi:10.1017/S1474691300001736. ISSN 1474-6913.

- Aperghis, Makis (2004). The Seleukid Royal Economy: The Finances and Financial Administration of the Seleukid Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45613-5.

- Appian (1899) [c. 150]. The Roman History of Appian of Alexandria. Vol. I: The Foreign Wars. Translated by White, Horace. The Macmillan Company. OCLC 582182174.

- Bar-Kochva, Bezalel (1976). The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns. Cambridge Classical Studies. Vol. 28. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20667-9.

- Bellinger, Alfred R. (1949). "The End of the Seleucids". Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 38. OCLC 4520682.

- Bennett, Christopher J. (2002). "Tryphaena". C. J. Bennett. The Egyptian Royal Genealogy Project hosted by the Tyndale House Website. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Bevan, Edwyn (2014) [1927]. A History of Egypt under the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Routledge Revivals. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-68225-7.

- Biers, William R. (1992). Art, Artefacts and Chronology in Classical Archaeology. Approaching the Ancient World. Vol. 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06319-7.

- Coloru, Omar (2015). "I Am Your Father! Dynasties and Dynastic Legitimacy on Pre-Islamic Coinage Between Iran and Northwest India". Electrum: Journal of Ancient History. Instytut Historii. Uniwersytet Jagielloński (Department of Ancient History at the Jagiellonian University). 22. ISSN 1897-3426.

- Den Dulk, Matthijs (2014). "Seleucus I Nicator in 4 Maccabees". Journal of Biblical Literature. The Society of Biblical Literature. 133 (1). ISSN 0021-9231.

- Downey, Robert Emory Glanville (2015) [1961]. A History of Antioch in Syria from Seleucus to the Arab Conquest. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-400-87773-7.

- Dumitru, Adrian (2016). "Kleopatra Selene: A Look at the Moon and Her Bright Side". In Coşkun, Altay; McAuley, Alex (eds.). Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire. Historia – Einzelschriften. Vol. 240. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 253–272. ISBN 978-3-515-11295-6. ISSN 0071-7665.

- Equini Schneider, Eugenia, ed. (1999a). "English Summary". Elaiussa Sebaste I: Campagne di Scavo, 1995–1997. Bibliotheca Archaeologica (in Italian). Vol. 24. L'Erma di Bretschneider. pp. 379–390. ISBN 978-8-882-65032-2.

- Equini Schneider, Eugenia (1999b). "II. Problematiche Storiche. 2. Elaiussa Sebaste. Dall'età Ellenistica Alla Tarda età Imperiale". In Equini Schneider, Eugenia (ed.). Elaiussa Sebaste I: Campagne di Scavo, 1995-1997. Bibliotheca Archaeologica (in Italian). Vol. 24. L'Erma di Bretschneider. pp. 33–42. ISBN 978-8-882-65032-2.

- Eusebius (1875) [c. 325]. Schoene, Alfred (ed.). Eusebii Chronicorum Libri Duo (in Latin). Vol. 1. Translated by Petermann, Julius Heinrich. Apud Weidmannos. OCLC 312568526.

- Grainger, John D. (1997). A Seleukid Prosopography and Gazetteer. Mnemosyne, Bibliotheca Classica Batava. Supplementum. Vol. 172. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-10799-1. ISSN 0169-8958.

- Habicht, Christian (2006). The Hellenistic Monarchies: Selected Papers. Translated by Stevenson, Peregrine. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11109-1.

- Hallo, William W. (1996). Origins. The Ancient Near Eastern Background of Some Modern Western Institutions. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 6. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10328-3. ISSN 0169-9024.

- Haym, Nicola Francesco (1719). The British Treasury; Being Cabinet the First of Our Greek and Roman Antiquities of All Sorts. Vol. 1. Printed in London. OCLC 931362821.

- Hoffmann, Otto (1906). Die Makedonen, ihre Sprache und ihr Volkstum. Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. OCLC 10854693.

- Hogg, Hope Waddell (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–187, see page 184.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (1998). "Notes on Some Imitation Drachms of Demetrius I Soter from Commagene". American Journal of Numismatics. second. American Numismatic Society. 10. ISSN 1053-8356.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2000). "A Dedication to Aphrodite Epekoos for Demetrius I Soter and His Family". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH. 131. ISSN 0084-5388.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2007). "A Revised Chronology for the Late Seleucids at Antioch (121/0–64 BC)". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. Franz Steiner Verlag. 56 (3): 280–301. doi:10.25162/historia-2007-0021. ISSN 0018-2311. S2CID 159573100.

- Houghton, Arthur (1987). "The Double Portrait Coins of Antiochus XI and Philip I: a Seleucid Mint at Beroea?". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. 66. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Houghton, Arthur; Moore, Wayne (1988). "Five Seleucid Notes". Museum Notes. The American Numismatic Society. 33. ISSN 0145-1413.

- Houghton, Arthur; Bendall, Simon (1988). "A Hoard of Aegean Tetradrachms and the Autonomous Tetradrachms of Elaeusa Sebast". Museum Notes. The American Numismatic Society. 33. ISSN 0145-1413.

- Houghton, Arthur (1989). "The Royal Seleucid Mint of Seleucia on the Calycadnus". In Le Rider, Georges Charles; Jenkins, Kenneth; Waggoner, Nancy; Westermark, Ulla (eds.). Kraay-Mørkholm Essays. Numismatic Studies in Memory of C.M. Kraay and O. Mørkholm. Numismatica Lovaniensia. Vol. 10. Université catholique de Louvain: Institut Supérieur d'Archéologie et d'Histoire de l'Art. Séminaire de Numismatique Marcel Hoc. OCLC 910216765.

- Houghton, Arthur; Müseler, Wilhelm (1990). "The Reigns of Antiochus VIII and Antiochus IX at Damascus". Schweizer Münzblätter. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Numismatik. 40 (159). ISSN 0016-5565.

- Houghton, Arthur (1992). "The Revolt of Tryphon and the Accession of Antiochus VI at Apamea: The Mints and Chronology of Antiochus VI and Tryphon". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. 71: 119–141. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Houghton, Arthur (1998). "The Struggle for the Seleucid Succession, 94–92 BC: a New Tetradrachm of Antiochus XI and Philip I of Antioch". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. 77. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Houghton, Arthur; Lorber, Catherine; Hoover, Oliver D. (2008). Seleucid Coins, A Comprehensive Guide: Part 2, Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. Vol. 1. The American Numismatic Society. ISBN 978-0-980-23872-3. OCLC 920225687.

- Howgego, Christopher (1995). Ancient History from Coins. Approaching the Ancient World. Vol. 4. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-08993-7.

- Humphreys, Henry Noel (1853). The Coin Collector's Manual, Or Guide to the Numismatic Student in the Formation of a Cabinet of Coins. Vol. 1. H. G. Bohn. OCLC 933156433.

- Josephus (1833) [c. 94]. Burder, Samuel (ed.). The Genuine Works of Flavius Josephus, the Jewish Historian. Translated by Whiston, William. Kimber & Sharpless. OCLC 970897884.

- Katičić, Radoslav (1976). Ancient Languages of the Balkans. Vol. 1. Mouton. OCLC 658109202.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire. A Historical Encyclopedia. Empires of the World. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-390-5.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- Langer, Ullrich (1994). Perfect Friendship: Studies in Literature and Moral Philosophy from Boccaccio to Corneille. Histoire des Idées et Critique Littéraire. Vol. 331. Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-00038-3. ISSN 0073-2397.

- Libanius (1992) [c. 356]. Fatouros, Georgios; Krischer, Tilman (eds.). Antiochikos (or. XI): Zur Heidnischen Renaissance in der Spätantike. Übersetzt und Kommentiert (in German). Verlag Turia & Kant. ISBN 978-3-851-32006-0.

- Lorber, Catharine C.; Iossif, Panagiotis (2009). "Seleucid Campaign Beards". L'Antiquité Classique. l’asbl L’Antiquité Classique. 78. ISSN 0770-2817.

- McGing, Brian C. (2010). Polybius' Histories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-71867-2.

- Meyer, Marion (2001). "Cilicia as Part of the Seleucid Empire. The Beginning of Municipal Coinage". In Jean, Eric; Dinçol, Ali M.; Durugönül, Serra (eds.). La Cilicie: Espaces et Pouvoirs Locaux (2e Millénaire av. J.-C. – 4e Siècle ap. J.-C.) Actes de la Table Ronde d'Istanbul, 2–5 Novembre 1999. Varia Anatolica. Vol. 13. l'Institut Français d'Études Anatoliennes. pp. 505–518. ISBN 978-2-906-05364-9.

- Ogden, Daniel (1999). Polygamy, Prostitutes and Death: The Hellenistic Dynasties. Duckworth with the Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 978-0-715-62930-7.

- Ogden, Daniel (2017). The Legend of Seleucus: Kingship, Narrative and Mythmaking in the Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-16478-9.

- Oktan, Mehmet (2011). "The Route Taken by Cilicia to Provincial Status: When and Why?". Olba: The Journal of Research Center for Cilician Archaeology. Mersin University Publications of the Research Center of Cilician Archaeology [KAAM]. 19. ISSN 1301-7667.

- Otto, Walter Gustav Albrecht; Bengtson, Hermann (1938). Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches: ein Beitrag zur Regierungszeit des 8. und des 9. Ptolemäers. Abhandlungen (Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse) (in German). Vol. 17. Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 470076298.

- Roussel, Pierre (1916). Délos, Colonie Athénienne. Bibliothèque des Ecoles Françaises d'Athènes et de Rome (in French). Vol. 111. Fontemoing & Cie, Éditeurs. OCLC 570766370.

- Roussel, Pierre; Launey, Marcel (1937). Décrets Postérieurs à 166 av. J.-C. (Nos. 1497–1524). Dédicaces Postérieures à 166 av. J.-C. (Nos. 1525–2219). Inscriptions de Délos. Par l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Fonds d'Epigraphie Grecque. Fondation du duc de Loubat (in French). Vol. IV. Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion. OCLC 2460433.

- Sumner, Graham Vincent (1978). "Governors of Asia in the Nineties B.C.". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. Duke University Press. 19. ISSN 2159-3159.

- Taylor, Michael J. (2013). Antiochus the Great. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-848-84463-6.

- Tempesta, Claudia (2013). "Central and Local Powers in Hellenistic Rough Cilicia". In Hoff, Michael C.; Townsend, Rhys F. (eds.). Rough Cilicia: New Historical and Archaeological Approaches. Proceedings of an International Conference Held at Lincoln, Nebraska, October 2007. Oxbow Books. pp. 27–42. ISBN 978-1-842-17518-7.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2011). "The Iconography of Succession Under the Late Seleukids". In Wright, Nicholas L. (ed.). Coins from Asia Minor and the East: Selections from the Colin E. Pitchfork Collection. The Numismatic Association of Australia. pp. 41–46. ISBN 978-0-646-55051-0.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2012). Divine Kings and Sacred Spaces: Power and Religion in Hellenistic Syria (301–64 BC). British Archaeological Reports (BAR) International Series. Vol. 2450. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-407-31054-1.

External links

- Seleukid history according to the Chronika of Porphyrios of Tyre (AD 232/3–305) preserved in the Chronikon (1.40) of Eusebios of Caesarea (AD 260–340) from the website of numismatist Oliver D. Hoover.

- The biography of Seleucus VI in the website of the numismatist Petr Veselý.