Revenue stamps of the United Kingdom refer to the various revenue or fiscal stamps, whether adhesive, directly embossed or otherwise, which were issued by and used in the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of Great Britain, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, from the late 17th century to the present day.

The first impressed duty stamps were issued by the Kingdom of England in accordance with the Stamps Act 1694. Impressed duty stamps were used to pay a multitude of taxes in the centuries since then, and they are still in use as of 2010.

The first adhesive revenue stamps were chocolate duty stamps issued in the 1740s, but no examples of these have survived today. The oldest known adhesive stamps of which examples still exist were issued in the 1780s for duties on hats, gloves and perfume. British revenue stamps therefore predate the first postage stamp, the Penny Black, which was issued in 1840. Surface printed revenues which had designs similar to postage stamps were first issued in 1853, and in 1855 embossed adhesive stamps began to be issued.

A wide range of revenue stamps were used throughout the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. These included standard key type designs bearing the portrait of the reigning monarch, embossed adhesives, impressed duty stamps and various other designs for specific uses. In most cases, stamps were affixed to documents but for some cases such as Medicine Duty, the stamp was affixed to the product being taxed.

The amount of revenue stamps in use decreased considerably during the 1960s, but key types and stamps for television licences continued to be issued until the late 1990s. The only revenue stamps still in use are impressed duty stamps, as well as taxpaid labels or imprints for alcohol excise. In addition to national issues, some of the constituent countries of the UK (Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Southern Ireland) issued their own revenue stamps due to peculiarities within the legal system. Some counties and local authorities also issued stamps during the 19th and 20th centuries. The extensive use of revenue stamps in the United Kingdom influenced the use of such stamps in its colonies.

Impressed duty stamps

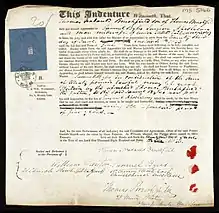

The first revenue stamps used in the United Kingdom were impressed duty stamps issued by the Kingdom of England following the introduction of Stamp Duty in the Stamps Act 1694.[1] This was An act for granting to Their Majesties several duties on Vellum, Parchment and Paper for 10 years, towards carrying on the war against France (5 & 6 Will. & Mar. c. 21).[2] The duty ranged from 1 penny to several shillings on a number of different legal documents including insurance policies and documents used as evidence in courts. It raised around £50,000 a year[3] and although it was initially a temporary measure, it proved so successful that its use was continued. Successive Acts have created new duties and impressed duty stamps are still in use to collect taxes, although electronic methods are now taking over. Around 10,000 different dies of impressed duty stamps have been used since the 17th century, and these exist with face values of up to £1 million.[1]

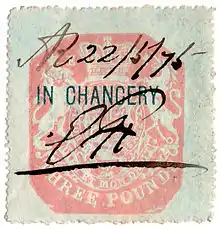

The tax was enforced by making the documents unenforceable in court if they had not been properly stamped. The tax was either a fixed amount per document or ad valorem where the tax varied according to the value of the transaction being taxed. Stamps were issued by the Board of Commissioners of Stamps. Distributors of stamps were appointed throughout the country. Later, the poet William Wordsworth was the distributor in Westmorland. At first, the stamps consisted of colourless (also known as albino) designs embossed directly onto a document using a die. Coloured ink in the embossed designs was introduced in the 1850s; initially this was pink but it was changed to vermilion in the 1870s. Blue ink was used for duplicate stamps.[1]

In the case of thick parchment such as vellum which did not allow for embossing directly on it, a paper was attached to the document using glue and a strip of tin, and the embossing was applied to this paper. A number of different coloured papers were used, including red, green, vermilion and most commonly blue. The ends of the strip of tin at the back of the document were covered with a small paper seal which bore the royal cypher of the reigning monarch. These were first introduced in 1701 under King William III, and continued to be used until 1921.[1]

Most of the embossed stamps were general-duty stamps, which were used for multiple purposes. However, at times there were specific issues inscribed for particular taxes or fees. Examples include Bill or Note[4] and Royal Courts of Justice.[5]

Adhesive revenue stamps

Embossed adhesives

By the mid-19th century, the use of impressed duty stamps had become extensive, and for convenience purposes the stamps began to be embossed onto sheets of gummed paper, and then cut down and subsequently affixed to documents.[1] The first adhesive general-duty revenue stamps were issued in 1855. The initial issue was imperforate, but from 1870 the stamps began to be perforated. The stamps were originally pink, but the colour was changed to vermilion in 1875 and blue in around 1887. Use of general-duty adhesive revenues continued until the early decades of the 20th century. Over-embossing dies, which are themselves very similar to impressed stamps, were often used as cancellations on embossed general-duty adhesives.[6]

Apart from general-duty revenues, there were also some embossed revenues issued for specific taxes. Sometimes the embossing was done on paper which had already been underprinted with inscriptions denoting the intended use, such as Customs[7] and Land Registry.[8] There were also specific designs of embossed stamps inscribed for a particular use, examples being Chancery Fee Fund[9] and Consular Service.[10]

Receipt, Draft and Inland Revenue stamps

In 1853, two 1d revenue stamps with designs depicting Queen Victoria and inscribed Receipt and Draft were issued. These stamps were surface printed by De La Rue, and their design resembles that of postage stamps, so many philatelists regard them as the first "true" adhesive revenue stamps.[1] In 1855, a single stamp inscribed Draft payable on demand, or Receipt was issued replacing the two separate issues.[11]

Inland Revenue stamps were introduced in 1860. Initially, the 1855 stamp was overprinted Inland Revenue, but sets of new stamps were issued later on that year. A number of Inland Revenue stamps were issued over the next two decades, both surface printed designs depicting Queen Victoria, as well as embossed adhesives with an underprint.[12]

The Customs and Inland Revenue Act of 1881 necessitated that dual-purpose stamps be issued for both postage and revenue. Therefore, the Penny Lilac was issued in July 1881 with the inscription Postage and Inland Revenue, superseding the older inland revenue stamps.[1] In 1883–84, a set of stamps known as the Lilac and Green Issue was introduced, and it bore the inscription Postage & Revenue. Later issues of postage stamps up to the 2/6 value also bore this inscription, and dual-purpose stamps continued to be issued until 1968. Fiscally used stamps are easily distinguished from their postally used counterparts since they were usually pen cancelled. Precancels with the names of firms were also commonly used.[1]

From 1904 to 1959, various Inland Revenue stamps with values from 3/- to 10/- were issued with key type designs.[12]

Key types

In 1872, a series of standard dies for revenue stamps were prepared by De La Rue. These designs depicted Queen Victoria and had a blank tablet at the bottom, which could then be overprinted with an inscription denoting for what the stamp was used for. They are therefore regarded as key type stamps. Each value had a different design, and the pence, shilling and pound values had different sizes.[1]

Upon the accession of King Edward VII, a set of new designs bearing the portrait of the new monarch was introduced. The same basic designs were reused with the portraits of King George V, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II, with some new values being added over the years. Initially, De La Rue was responsible for both making the printing plates and printing the stamps. In 1910, printing was taken over by the Stamp Office. At first the existing De La Rue plates continued to be used, until the Royal Mint took over the work of making the plates in 1915. His Majesty's Stationery Office became responsible for the printing in 1934.[1]

In 1971, new stamps had to be printed due to decimalization, and both the printing plates and the printing itself was carried out by De La Rue. The quality of printing declined substantially in the late 1970s, as the printing might have been subcontracted. A new key type was introduced in around 1990 but it was only used for a few stamps as by then, the amount of revenue stamps that were in use had decreased considerably.[1]

Examples of appropriations on the key types include Bankruptcy,[13] Contract Note,[14] Foreign Bill[15] and Passport.[16]

Other designs

Apart from the embossed stamps and the key types, a number of other fees or taxes had their own stamps. Many stamps issued in the 19th century depicted Queen Victoria, examples of these being stamps for Admiralty Court fees,[17] early Foreign Bill stamps,[15] Life Policy stamps[18] and stamps for Matrimonial Cause Fees.[19] Other stamps which had their own specific designs include issues for Annuity Premium[20] and Old Age Pensions.[21] Excise stamps were used to pay the duty on entertainment activities from 1916 to 1958, and were affixed to cinema or event tickets.[22]

Small numeral designs were utilized for many contributions stamps, such as those issued for National Health Insurance (1912–25), Health and Pensions Insurance (1925–48)[23] and National Insurance (1948–90s).[23] Other related issues include Unemployment Insurance[24] and Agriculture Unemployment Insurance stamps, which were superseded by NI issues in 1948.[25]

The UK issued television licence stamps from 1972 until these were withdrawn in 1998.[26] CB radio licence stamps were also issued between 1981 and the 1990s.[27]

Stamps affixed onto the taxed object

Duty stamps which were affixed directly to the object they were taxing were first issued in the 18th century, making them first adhesive revenue stamps to be issued. They usually had no gum and were glued to the object being taxed. Most of them would be destroyed upon opening the packaging.[1] Early issues and the date of first issue include stamps for chocolate duty (c. 1743),[28] hat tax (1784),[29] glove duty (1785),[30] perfume duty (1786)[31] and cocoa duty (1822).[32] No chocolate duty stamps seem to still exist today.[28]

A wide range of large-format stamps were issued to pay for Medicine Duty. These were affixed directly to jars or packets of medicine, and many different types exist, both standard issues as well as appropriated ones with the manufacturer's brand specified on the stamp. Medicine duty stamps were first introduced in 1783 and remained in use until 1941.[33] In 1915, two King George V postage and revenue stamps were overprinted to pay for additional medicine duty. This was done after duty rates had doubled, and the stamps were affixed over large-format stamps with the old face values.[34]

Large-format stamps were also issued to pay duty on cavendish tobacco and coffee mixtures from the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries.[27][35] Duty stamps paying the tax on spirits and wine are still in use as of 2017, and they are affixed or imprinted on the alcohol container.[36]

Other types of revenue stamps

When something other than a document was taxed, sometimes labels were affixed to the object's packaging to indicate that the tax had been paid (see § Stamps affixed onto the taxed object), but this was not always the case. Sometimes the item itself or its wrapper were imprinted with a revenue stamp, in what may be regarded as the fiscal equivalent of postal stationery. Examples of this include taxes on:[1]

- Dice – each die had to have a mark impressed with a metal punch

- Newspapers – stamps were imprinted directly onto the margin of the paper

- Playing cards – the wrappers of the pack of cards had to have tax paid marks or imprints

- Wallpaper – stamps were printed on the backs of sheets of wallpaper

Tickets issued for horse duty in the 18th century are sometimes also regarded and collected as revenue stamps.[1]

Excise stamps were also directly imprinted on cinema tickets in 1916–58[22] and betting tickets in 1926–29.[4]

Ireland and Scotland

Despite being part of the United Kingdom, Ireland had many unique branches of the legal system, and this necessitated the need for some separate revenue stamps. Impressed duty stamps were introduced in Ireland in 1774, at the time when it was a separate kingdom and a client state of Britain. The designs of most Irish revenues were very similar to British issues (including many impressed duty stamps, embossed adhesives or key types), but some impressed duty stamps bore Irish symbols such as the harp. Examples of Irish revenues issued when it was part of the United Kingdom include stamps for Admiralty Court, County Courts, Dog Licence and Land Registry.[37]

When Ireland was partitioned into Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland in 1921, separate revenue stamps were issued for both entities. Southern Ireland stamps saw little use since that political entity was quickly superseded by the Provisional Government of Ireland and later the Irish Free State (both of which applied overprints on various British and Irish revenue stamps).[37] However, Northern Ireland continued to use separate revenue stamps until the 1980s. Northern Irish revenues include Civil Service, Dog Licence, Excise and National Insurance stamps, among many others.[38]

A similar situation existed to a lower extent with Scotland, whose legal system had some differences from the rest of the country. The only revenue stamps issued specifically for Scotland were Law Courts stamps between 1873 and the 1970s,[39] and Register House stamps between 1871 and the 1950s.[40]

County and city issues

The Local Stamp Act of 1869 permitted local authorities to issue their own stamps to collect certain fines or fees. In 1870, the counties of Gloucestershire, Isle of Ely and Northamptonshire introduced a common design consisting of a shield with the Union Jack, with the name of the county above it and the face value of the stamp below. The colours of the stamps determined what function they were to be used for, usually County Court fees or fines. Some stamps are also known overprinted Gaol for cases where fines were paid late and the person was subsequently sent to prison. These county stamps were discontinued by the 1880s.[30][41][42]

The City of London issued and used Justice Room stamps from 1869 to around 1960, and Mayor's Court stamps from 1883 to around 1939. A single stamp was issued to pay for Guildhall Consultation Fees in 1892, and this was used until about 1900. None of these stamps bears the name of the city, but they all depict the coat of arms of the City of London.[43][44][45]

The Chatham and Sheerness Police Courts issued a few stamps from around 1870 to 1897.[28] The Chancery of Lancashire used various types of typeset stamps as fee receipts from 1875 to 1971.[46] The Town of Southampton and the County of Southton (the latter referring to all of Hampshire except for Southampton itself) issued Court Fee and Fine or Fee stamps respectively in 1878 and 1880.[47] Winchester issued Justice Court stamps in 1888 and used them until around 1900.[48] Sheffield issued Town Hall and Court House stamps in 1891, and these remained in use until around 1905.[49] Hampshire used stamps for Land Charges search fees between 1962 and 1976.[43]

In 1979, key type designs for home help, home care or meals on wheels were introduced by various local authorities. These are not revenues since they were optional home support services not taxes.[50] The Nottinghamshire County Council used one such keytype to pay for housing fees and social services in the 1990s.[21]

Crown dependencies

The three Crown dependencies – Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man – are not officially part of the United Kingdom but are self-governing possessions of the Crown. As such, they issued revenue stamps separately from the United Kingdom. The Isle of Man used British key types from 1889 to 1966, and overprints on British National Health Insurance, Health and Pensions Insurance, and National Insurance stamps from around 1920 to the 1970s.[51] Post-1966 Isle of Man revenues, as well as stamps issued by the States of Guernsey and the States of Jersey had different designs which were unrelated to revenue stamps used in the United Kingdom.[52] The States of Alderney also issued revenue stamps from 1923 to 1962.[25] Jersey revenues are still in use.[53]

Apart from separate issues by each of the islands, general stamps for all the Channel Islands were issued in 1973 to prepay the British Value-added tax on boxes of flowers sent by post.[54]

Colonies

Some colonies followed Britain in the use of duty stamps in the 18th century. Embossed or directly imprinted revenue stamps were used by the Province of Massachusetts Bay and Province of New York in 1755–57 and 1757–60 respectively.[55][56] The Stamp Act 1765 introduced direct taxation in the colonies of British America, and a series of impressed duty stamps were therefore introduced in these colonies. They had similar designs to British issues but with the inscription America, and like British issues the stamps could be embossed directly onto a document or on pieces of coloured paper with a cypher label at the back.[56][1] Apart from general-duty impressed stamps, embossed stamps for playing cards and imprinted stamps for almanacs and newspapers or pamphlets were also prepared or issued. Some of these are only known as proofs and not as issued stamps.[1] The Stamp Act brought about the objection of "no taxation without representation", and it was a major contributing factor to the American Revolution.[56]

Most of the various British colonies, protectorates and territories issued impressed duty stamps or adhesive revenue stamps (or both) at some points during the 19th and 20th centuries.[57] The Colony of Jamaica might have used impressed duty stamps as early as 1804,[58] while Mauritius was using inked impressions for revenue purposes in the 1820s.[59] Early users of adhesive revenue stamps include Jamaica, which issued surface printed revenue stamps in 1855,[58] and the Colony of Natal, which roughly at the same time issued embossed adhesives similar to those used in Britain.[60]

Some British revenue stamps were also overprinted for use in the colonies. Impressed duty stamps were overprinted for use in the protectorate of Cyprus.[61] Embossed adhesives were overprinted for use in Barbados,[62] the British Solomon Islands,[63] Jamaica[64] and Trinidad and Tobago.[65] British key types were also overprinted for use as postage and revenue stamps of British Bechuanaland,[66] as revenue stamps of Cyprus[67] and Weihaiwei,[68] and as court fee stamps of the Trucial States.[69] The key types were also used to produce Military Telegraphs and Army Telegraphs stamps of the United Kingdom.[70] British postage and revenue stamps were also overprinted for use as revenues in Mandatory Palestine.[61][71]

See also

- British Library Philatelic Collections

- Postage stamps and postal history of Great Britain

- Revenue Society

- Walter Morley, author on a number of books about UK revenue stamps

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Barefoot 2010, pp. 3–10

- ↑ Russell 2000, p. 27

- ↑ Rabushka 2010, p. 291

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, p. 23

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 164

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 11–12

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 41–43

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 108–110

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 26

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 46

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, pp. 70–72

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 21–23

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 38–40

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, pp. 50–53

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 149

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 16

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 113–114

- ↑ "Matrimonial Cause Revenue Stamps". Sandafayre. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 18

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, p. 147

- 1 2 McClellan, Andrew (2016–2018). "Great Britain and Ireland Excise Revenue". Revenue Reverend. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018.

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, pp. 62–63

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 173–175

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, p. 17

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 169–170

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, p. 25

- 1 2 3 Barefoot 2010, p. 28

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 61

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, p. 55

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 152

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 29

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 121–128

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 15

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 30

- ↑ "Excise Notice DS5: UK Duty Stamps Scheme". Gov.UK. 7 September 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2018.

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, pp. 73–91

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 138–146

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 111–112

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 163–164

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 91–92

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 137–138

- 1 2 Barefoot 2010, p. 60

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 106

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 120

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 107

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 166

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 177

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 165

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 63

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 92–99

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 56–59

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, pp. 99–103

- ↑ Barefoot 2010, p. 27

- ↑ Lindquist, H. L. (1947). "Stamped Revenue Paper". Stamp Specialist (18): 75.

- 1 2 3 "Stamp from the Stamp Act of 1765". National Postal Museum. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016.

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, p. 3

- 1 2 McClellan, Andrew (2011–2018). "Jamaica". Revenue Reverend. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. citing Barber, W. (2009). The Impressed Duty Stamps of the British Colonial Empire. Chesapeake, Virginia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ McClellan, Andrew (2012–2014). "Mauritius". Revenue Reverend. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, p. 369

- 1 2 "British adhesive Revenue stamps overprinted for use outside England, Wales and Scotland, and postage stamps overprinted for revenue use". GB Overprints Society. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, pp. 75–78

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, pp. 95–96

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, pp. 235–238

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, pp. 400–402

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, p. 82

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, p. 148

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, p. 405

- ↑ Barefoot 2012, pp. 403–404

- ↑ Panting, Steve. "Military and Army Telegraphs". gb-precancels.org. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017., citing Hiscocks, S. E. R. (1982). Telegraph & Telephone Stamps of the World: A Priced and Annotated Catalogue. ISBN 978-0950830100.

- ↑ McClellan, Andrew (2013–2016). "Palestine". Revenue Reverend. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Barefoot, John (2012). British Commonwealth Revenues (9 ed.). York: J. Barefoot Ltd. ISBN 978-0906845721.

- Barefoot, John (2010). United Kingdom Revenues (5 ed.). York: J. Barefoot Ltd. ISBN 978-0906845691.

- Rabushka, Alvin (2010). Taxation in Colonial America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400828708.

- Russell, David Lee (2000). The American Revolution in the Southern Colonies. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786407835.

External links

- GB Revenue Stamp Archive vol. 1, 2, 3 – gallery of various British revenue stamps by I.B RedGuy's Fine Stamps

- Great Britain Revenue Duties from 1694 to the Great Reform of 1853 – exhibit by Chris Harman RDP FRPSL (You have to manually change the page number, i.e., 2.jpg, etc., to view next pages).

- Great Britain Revenue Stamps Printed by Perkins Bacon – exhibit by Frank Walton RDP FRPSL