The partition of Ireland (Irish: críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. It was enacted on 3 May 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The Act intended both territories to remain within the United Kingdom and contained provisions for their eventual reunification. The smaller Northern Ireland was duly created with a devolved government (Home Rule) and remained part of the UK. The larger Southern Ireland was not recognised by most of its citizens, who instead recognised the self-declared 32-county Irish Republic. On 6 December 1922, a year after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the territory of Southern Ireland left the UK and became the Irish Free State, now the Republic of Ireland.

The territory that became Northern Ireland, within the Irish province of Ulster, had a Protestant and Unionist majority who wanted to maintain ties with Britain. This was largely due to 17th-century British colonisation. However, it also had a significant minority of Catholics and Irish nationalists. The rest of Ireland had a Catholic, nationalist majority who wanted self-governance or independence. The Irish Home Rule movement compelled the British government to introduce bills that would give Ireland a devolved government within the UK (home rule). This led to the Home Rule Crisis (1912–14), when Ulster unionists/loyalists founded a paramilitary movement, the Ulster Volunteers, to prevent Ulster being ruled by an Irish government. The British government proposed to exclude all or part of Ulster, but the crisis was interrupted by the First World War (1914–18). Support for Irish independence grew during the war.

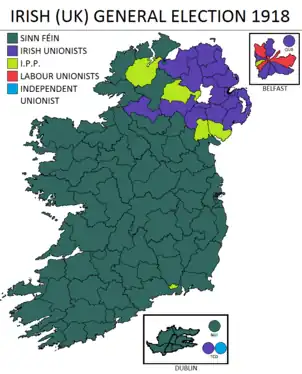

Irish republican party Sinn Féin won the vast majority of Irish seats in the 1918 election. They formed a separate Irish parliament and declared an independent Irish Republic covering the whole island. This led to the Irish War of Independence (1919–21), a guerrilla conflict between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces. In 1920 the British government introduced another bill to create two devolved governments: one for six northern counties (Northern Ireland) and one for the rest of the island (Southern Ireland). This was passed as the Government of Ireland Act,[1] and came into force as a fait accompli on 3 May 1921.[2] Following the 1921 elections, Ulster unionists formed a Northern Ireland government. A Southern government was not formed, as republicans recognised the Irish Republic instead. During 1920–22, in what became Northern Ireland, partition was accompanied by violence "in defence or opposition to the new settlement" – see The Troubles in Northern Ireland (1920–1922). The capital, Belfast, saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence, mainly between Protestant and Catholic civilians.[3] More than 500 were killed[4] and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them from the Catholic minority.[5]

The War of Independence resulted in a truce in July 1921 and led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty that December. Under the Treaty, the territory of Southern Ireland would leave the UK and become the Irish Free State. Northern Ireland's parliament could vote it in or out of the Free State, and a commission could then redraw or confirm the provisional border. In early 1922, the IRA launched a failed offensive into border areas of Northern Ireland. The Northern government chose to remain in the UK.[6] The Boundary Commission proposed small changes to the border in 1925, but they were not implemented.

Since partition, Irish nationalists/republicans continued to seek a united independent Ireland, while Ulster unionists/loyalists wanted Northern Ireland to remain in the UK. The Unionist governments of Northern Ireland were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority. Unionists opposed a campaign to end discrimination, viewing it as a republican front.[7] This sparked the Troubles (c. 1969–1998), a thirty-year conflict in which more than 3,500 people were killed. Under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the Irish and British governments and the main parties agreed to a power-sharing government in Northern Ireland, and that the status of Northern Ireland would not change without the consent of a majority of its population.[8] The treaty also reaffirmed an open border between both jurisdictions.[9][10]

Background

Irish Home Rule movement

During the 19th century, the Irish nationalist Home Rule movement campaigned for Ireland to have self-government while remaining part of the United Kingdom. The nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party won most Irish seats in the 1885 general election. It then held the balance of power in the British House of Commons, and entered into an alliance with the Liberals. IPP leader Charles Stewart Parnell convinced British Prime Minister William Gladstone to introduce the First Irish Home Rule Bill in 1886. Protestant unionists in Ireland opposed the Bill, fearing industrial decline and religious persecution of Protestants by a Catholic-dominated Irish government. English Conservative politician Lord Randolph Churchill proclaimed: "the Orange card is the one to play", in reference to the Protestant Orange Order. The belief was later expressed in the popular slogan, "Home Rule means Rome Rule".[11] Partly in reaction to the Bill, there were riots in Belfast, as Protestant unionists attacked the city's Catholic nationalist minority. The Bill was defeated in the Commons.[12]

Gladstone introduced a Second Irish Home Rule Bill in 1892. The Irish Unionist Alliance had been formed to oppose home rule, and the Bill sparked mass unionist protests. In response, Liberal Unionist leader Joseph Chamberlain called for a separate provincial government for Ulster where Protestant unionists were a majority.[13] Irish unionists assembled at conventions in Dublin and Belfast to oppose both the Bill and the proposed partition.[14] The unionist MP Horace Plunkett, who would later support home rule, opposed it in the 1890s because of the dangers of partition.[15] Although the Bill was approved by the Commons, it was defeated in the House of Lords.[12]

Home Rule Crisis

Following the December 1910 election, the Irish Parliamentary Party again agreed to support a Liberal government if it introduced another home rule bill.[16] The Parliament Act 1911 meant the House of Lords could no longer veto bills passed by the Commons, but only delay them for up to two years.[16] British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith introduced the Third Home Rule Bill in April 1912.[17] Unionists opposed the Bill, but argued that if Home Rule could not be stopped then all or part of Ulster should be excluded from it.[18] Irish nationalists opposed partition, although some were willing to accept Ulster having some self-governance within a self-governing Ireland ("Home Rule within Home Rule").[19] Winston Churchill made his feelings about the possibility of the partition of Ireland clear: "Whatever Ulster's right may be, she cannot stand in the way of the whole of the rest of Ireland. Half a province cannot impose a permanent veto on the nation. Half a province cannot obstruct forever the reconciliation between the British and Irish democracies."[20] In September 1912, more than 500,000 Unionists signed the Ulster Covenant, pledging to oppose Home Rule by any means and to defy any Irish government.[21] They founded a large paramilitary movement, the Ulster Volunteers, to prevent Ulster becoming part of a self-governing Ireland. They also threatened to establish a Provisional Ulster Government. In response, Irish nationalists founded the Irish Volunteers to ensure Home Rule was implemented.[22] The Ulster Volunteers smuggled 25,000 rifles and three million rounds of ammunition into Ulster from the German Empire, in the Larne gun-running of April 1914. The Irish Volunteers also smuggled weaponry from Germany in the Howth gun-running that July. Ireland seemed to be on the brink of civil war.[23] Three border boundary options were proposed.[24]

On 20 March 1914, in the "Curragh incident", many of the highest-ranking British Army officers in Ireland threatened to resign rather than deploy against the Ulster Volunteers.[25] This meant that the British government could legislate for Home Rule but could not be sure of implementing it.[26] In May 1914, the British government introduced an Amending Bill to allow for 'Ulster' to be excluded from Home Rule. There was then debate over how much of Ulster should be excluded and for how long, and whether to hold referendums in each county. The Chancellor of the Exchequer Lloyd George supported "the principle of the referendum...each of the Ulster Counties is to have the option of exclusion from the Home Rule Bill."[27] Some Ulster unionists were willing to tolerate the 'loss' of some mainly-Catholic areas of the province.[28] In July 1914, King George V called the Buckingham Palace Conference to allow Unionists and Nationalists to come together and discuss the issue of partition, but the conference achieved little.[29]

First World War

The Home Rule Crisis was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, and Ireland's involvement in it. Asquith abandoned his Amending Bill, and instead rushed through a new bill, the Suspensory Act 1914, which received Royal Assent together with the Home Rule Bill (now Government of Ireland Act 1914) on 18 September 1914. The Suspensory Act ensured that Home Rule would be postponed for the duration of the war[30] with the exclusion of Ulster still to be decided.[31]

During the First World War, support grew for full Irish independence, which had been advocated by Irish republicans. In April 1916, republicans took the opportunity of the war to launch a rebellion against British rule, the Easter Rising. It was crushed after a week of heavy fighting in Dublin. The harsh British reaction to the Rising fuelled support for independence, with republican party Sinn Féin winning four by-elections in 1917.[32]

The British parliament called the Irish Convention in an attempt to find a solution to its Irish Question. It sat in Dublin from July 1917 until March 1918, and comprised both Irish nationalist and Unionist politicians. It ended with a report, supported by nationalist and southern unionist members, calling for the establishment of an all-Ireland parliament consisting of two houses with special provisions for Ulster unionists. The report was, however, rejected by the Ulster unionist members, and Sinn Féin had not taken part in the proceedings, meaning the convention was a failure.[33][34]

In 1918, the British government attempted to impose conscription in Ireland and argued there could be no Home Rule without it.[35] This sparked outrage in Ireland and further galvanised support for the republicans.[36]

1918 General Election, Long Committee, violence

In the December 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won the overwhelming majority of Irish seats. In line with their manifesto, Sinn Féin's elected members boycotted the British parliament and founded a separate Irish parliament (Dáil Éireann), declaring an independent Irish Republic covering the whole island. Unionists, however, won most seats in northeastern Ulster and affirmed their continuing loyalty to the United Kingdom.[37] Many Irish republicans blamed the British establishment for the sectarian divisions in Ireland, and believed that Ulster Unionist defiance would fade once British rule was ended.[38]

The British authorities outlawed the Dáil in September 1919,[39] and a guerrilla conflict developed as the Irish Republican Army (IRA) began attacking British forces. This became known as the Irish War of Independence.[40][41]

Long Committee - Six or Nine Counties

In September 1919, British Prime Minister Lloyd George tasked a committee with planning Home Rule for Ireland within the UK. Headed by English Unionist politician Walter Long, it was known as the 'Long Committee'. The makeup of the committee was Unionist in outlook and had no Nationalist representatives as members. James Craig (the future 1st Prime Minister of Northern Ireland) and his associates were the only Irishmen consulted during this time.[42] During the summer of 1919, Long visited Ireland several times, using his yacht as a meeting place to discuss the "Irish question" with the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland John French and the Chief Secretary for Ireland Ian Macpherson.[43]

Prior to the first meeting of the committee, Long sent a memorandum to the British Prime Minister recommending two parliaments for Ireland (24 September 1919). That memorandum formed the basis of the legislation that partitioned Ireland – the Government of Ireland Act 1920.[43][44] At the first meeting of the committee (15 October 1919) it was decided that two devolved governments should be established — one for the nine counties of Ulster and one for the rest of Ireland, together with a Council of Ireland for the "encouragement of Irish unity".[45] The Long Committee felt that the nine-county proposal "will enormously minimise the partition issue...it minimises the division of Ireland on purely religious lines. The two religions would not be unevenly balanced in the Parliament of Northern Ireland."[46] Most northern unionists wanted the territory of the Ulster government to be reduced to six counties, so that it would have a larger Protestant/Unionist majority. Long offered the Committee members a deal – "that the Six Counties ... should be theirs for good ... and no interference with the boundaries".[47] This left large areas of Northern Ireland with populations that supported either Irish Home Rule or the establishment of an all-Ireland Republic. The results from the last all-Ireland election (the 1918 Irish general election) showed Nationalist majorities in the envisioned Northern Ireland: Counties Tyrone and Fermanagh, Derry City and the Constituencies of Armagh South, Belfast Falls and Down South.[48]

Many Unionists feared that the territory would not last if it included too many Catholics and Irish Nationalists but any reduction in size would make the state unviable. The six counties of Antrim, Down, Armagh, Londonderry, Tyrone and Fermanagh comprised the maximum area unionists believed they could dominate.[49] The remaining three Counties of Ulster had large Catholic majorities: Cavan 81.5%, Donegal 78.9% and Monaghan 74.7%.[50] On 29 March 1920 Charles Craig (son of Sir James Craig and Unionist MP for County Antrim) made a speech in the British House of Commons where he made clear the future make up of Northern Ireland: "The three Ulster counties of Monaghan, Cavan and Donegal are to be handed over to the South of Ireland Parliament. How the position of affairs in a Parliament of nine counties and in a Parliament of six counties would be is shortly this. If we had a nine counties Parliament, with 64 members, the Unionist majority would be about three or four, but in a six counties Parliament, with 52 members, the Unionist majority, would be about ten. The three excluded counties contain some 70,000 Unionists and 260,000 Sinn Feiners and Nationalists, and the addition of that large block of Sinn Feiners and Nationalists would reduce our majority to such a level that no sane man would undertake to carry on a Parliament with it. That is the position with which we were faced when we had to take the decision a few days ago as to whether we would call upon the Government to include the nine counties in the Bill or be settled with the six."[51]

In the 1921 elections in Northern Ireland, Fermanagh – Tyrone (which was a single constituency), showed Catholic/Nationalist majorities: 54.7% Nationalist / 45.3% Unionist.[52] In a letter dated 7 September 1921 from Lloyd George to the President of the Irish Republic Eamon de Valera regarding Counties Fermanagh and Tyrone, the British Prime Minister stated that his government had a very weak case on the issue "of forcing these two Counties against their will" into Northern Ireland.[53] On 28 November 1921 both Tyrone and Fermanagh County Councils declared allegiance to the new Irish Parliament (Dail). On 2 December the Tyrone County Council publicly rejected the "...arbitrary, new-fangled, and universally unnatural boundary". They pledged to oppose the new border and to "make the fullest use of our rights to mollify it".[54] On 21 December 1921 the Fermanagh County Council passed the following resolution: "We, the County Council of Fermanagh, in view of the expressed desire of a large majority of people in this county, do not recognise the partition parliament in Belfast and do hereby direct our Secretary to hold no further communications with either Belfast or British Local Government Departments, and we pledge our allegiance to Dáil Éireann." Shortly afterwards, Dawson Bates the long time (1921-1923) Minister of Home Affairs (Northern Ireland) authorized that both County Councils offices be seized (by the Royal Irish Constabulary), the County officials expelled, and the County Councils dissolved.[55]

Violence

In what became Northern Ireland, the process of partition was accompanied by violence, both "in defense or opposition to the new settlement".[3] The IRA carried out attacks on British forces in the north-east, but was less active than in the south of Ireland. Protestant loyalists in the north-east attacked the Catholic minority in reprisal for IRA actions. The January and June 1920 local elections saw Irish nationalists and republicans win control of Tyrone and Fermanagh county councils, which were to become part of Northern Ireland, while Derry had its first Irish nationalist mayor.[56][57] In summer 1920, sectarian violence erupted in Belfast and Derry, and there were mass burnings of Catholic property by loyalists in Lisburn and Banbridge.[58] Loyalists drove 8,000 "disloyal" co-workers from their jobs in the Belfast shipyards, all of them either Catholics or Protestant labour activists.[59] In his Twelfth of July speech, Unionist leader Edward Carson had called for loyalists to take matters into their own hands to defend Ulster, and had linked republicanism with socialism and the Catholic Church.[60] In response to the expulsions and attacks on Catholics, the Dáil approved a boycott of Belfast goods and banks. The 'Belfast Boycott' was enforced by the IRA, who halted trains and lorries from Belfast and destroyed their goods.[61] Conflict continued intermittently for two years, mostly in Belfast, which saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence between Protestant and Catholic civilians. There was rioting, gun battles and bombings. Homes, business and churches were attacked and people were expelled from workplaces and from mixed neighbourhoods.[3] The British Army was deployed and an Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) was formed to help the regular police. The USC was almost wholly Protestant and some of its members carried out reprisal attacks on Catholics.[62] From 1920 to 1922, more than 500 were killed in Northern Ireland[63] and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them Catholics.[5] See The Troubles in Northern Ireland (1920–1922).

.jpg.webp)

Government of Ireland Act 1920

The British government introduced the Government of Ireland Bill in early 1920 and it passed through the stages in the British parliament that year. It would partition Ireland and create two self-governing territories within the UK, with their own bicameral parliaments, along with a Council of Ireland comprising members of both. Northern Ireland would comprise the aforesaid six northeastern counties, while Southern Ireland would comprise the rest of the island.[64] The Act was passed on 11 November and received royal assent in December 1920. It would come into force on 3 May 1921.[65][66] Elections to the Northern and Southern parliaments were held on 24 May. Unionists won most seats in Northern Ireland. Its parliament first met on 7 June and formed its first devolved government, headed by Unionist Party leader James Craig. Republican and nationalist members refused to attend. King George V addressed the ceremonial opening of the Northern parliament on 22 June.[65] Meanwhile, Sinn Féin won an overwhelming majority in the Southern Ireland election. They treated both as elections for Dáil Éireann, and its elected members gave allegiance to the Dáil and Irish Republic, thus rendering "Southern Ireland" dead in the water.[67] The Southern parliament met only once and was attended by four unionists.[68]

On 5 May 1921, the Ulster Unionist leader Sir James Craig met with the President of Sinn Féin, Éamon de Valera, in secret near Dublin. Each restated his position and nothing new was agreed. On 10 May De Valera told the Dáil that the meeting "... was of no significance".[69] In June that year, shortly before the truce that ended the Anglo-Irish War, David Lloyd George invited the Republic's President de Valera to talks in London on an equal footing with the new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, which de Valera attended. De Valera's policy in the ensuing negotiations was that the future of Ulster was an Irish-British matter to be resolved between two sovereign states, and that Craig should not attend.[70] After the truce came into effect on 11 July, the USC was demobilized (July – November 1921).[71] Speaking after the truce Lloyd George made it clear to de Valera, 'that the achievement of a republic through negotiation was impossible'.[72]

On 20 July, Lloyd George further declared to de Valera that:

The form in which the settlement is to take effect will depend upon Ireland herself. It must allow for full recognition of the existing powers and privileges of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, which cannot be abrogated except by their own consent. For their part, the British Government entertain an earnest hope that the necessity of harmonious co-operation amongst Irishmen of all classes and creeds will be recognised throughout Ireland, and they will welcome the day when by those means unity is achieved. But no such common action can be secured by force.[73]

In reply, de Valera wrote

We most earnestly desire to help in bringing about a lasting peace between the peoples of these two islands, but see no avenue by which it can be reached if you deny Ireland's essential unity and set aside the principle of national self-determination.[73]

Speaking in the House of Commons on the day the Act passed, Joe Devlin (Nationalist Party) representing west Belfast, summed up the feelings of many Nationalists concerning partition and the setting up of a Northern Ireland Parliament while Ireland was in a deep state of unrest. Devlin stated:

"I know beforehand what is going to be done with us, and therefore it is well that we should make our preparations for that long fight which, I suppose, we will have to wage in order to be allowed even to live." He accused the government of "...not inserting a single clause...to safeguard the interests of our people. This is not a scattered minority...it is the story of weeping women, hungry children, hunted men, homeless in England, houseless in Ireland. If this is what we get when they have not their Parliament, what may we expect when they have that weapon, with wealth and power strongly entrenched? What will we get when they are armed with Britain's rifles, when they are clothed with the authority of government, when they have cast round them the Imperial garb, what mercy, what pity, much less justice or liberty, will be conceded to us then? That is what I have to say about the Ulster Parliament."[74]

Ulster Unionist Party politician Charles Craig (the brother of Sir James Craig) made the feelings of many Unionists clear concerning the importance they placed on the passing of the Act and the establishment of a separate Parliament for Northern Ireland:

"The Bill gives us everything we fought for, everything we armed ourselves for, and to attain which we raised our Volunteers in 1913 and 1914...but we have many enemies in this country, and we feel that an Ulster without a Parliament of its own would not be in nearly as strong a position...where, above all, the paraphernalia of Government was already in existence...We should fear no one and would be in a position of absolute security."[75]

In reference to the threat of Unionist violence and the achievement of a separate status of Ulster, Winston Churchill felt that "...if Ulster had confined herself simply to constitutional agitation, it is extremely improbable that she would have escaped inclusion in a Dublin Parliament."[76]

Anglo-Irish Treaty

.jpg.webp)

The Irish War of Independence led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, between the British government and representatives of the Irish Republic. Negotiations between the two sides were carried on between October and December 1921. The British delegation consisted of experienced parliamentarians/debaters such as Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Austen Chamberlain and Lord Birkenhead, they had clear advantages over the Sinn Féin negotiators.[77] The Treaty was signed on 6 December 1921. Under its terms, the territory of Southern Ireland would leave the United Kingdom within one year and become a self-governing dominion called the Irish Free State. The treaty was given legal effect in the United Kingdom through the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922, and in Ireland by ratification by Dáil Éireann. Under the former Act, at 1 pm on 6 December 1922, King George V (at a meeting of his Privy Council at Buckingham Palace)[78] signed a proclamation establishing the new Irish Free State.[79]

Under the treaty, Northern Ireland's parliament could vote to opt out of the Free State.[80] Under Article 12 of the Treaty,[81] Northern Ireland could exercise its opt-out by presenting an address to the King, requesting not to be part of the Irish Free State. Once the treaty was ratified, the Houses of Parliament of Northern Ireland had one month (dubbed the Ulster month) to exercise this opt-out during which time the provisions of the Government of Ireland Act continued to apply in Northern Ireland. According to legal writer Austen Morgan, the wording of the treaty allowed the impression to be given that the Irish Free State temporarily included the whole island of Ireland, but legally the terms of the treaty applied only to the 26 counties, and the government of the Free State never had any powers—even in principle—in Northern Ireland.[82] On 7 December 1922 the Parliament of Northern Ireland approved an address to George V, requesting that its territory not be included in the Irish Free State. This was presented to the king the following day and then entered into effect, in accordance with the provisions of Section 12 of the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act 1922.[83] The treaty also allowed for a re-drawing of the border by a Boundary Commission.[84]

Unionist objections to the Treaty

Sir James Craig, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland objected to aspects of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In a letter to Austen Chamberlain dated 14 December 1921, he stated:

We protest against the declared intention of your government to place Northern Ireland automatically in the Irish Free State. Not only is this opposed to your pledge in our agreed statement of November 25th, but it is also antagonistic to the general principles of the Empire regarding her people's liberties. It is true that Ulster is given the right to contract out, but she can only do so after automatic inclusion in the Irish Free State. [...] We can only conjecture that it is a surrender to the claims of Sinn Fein that her delegates must be recognised as the representatives of the whole of Ireland, a claim which we cannot for a moment admit. [...] The principles of the 1920 Act have been completely violated, the Irish Free State being relieved of many of her responsibilities towards the Empire. [...] We are glad to think that our decision will obviate the necessity of mutilating the Union Jack.[85][86]

Nationalist objections to the Government of Ireland Act & the Anglo Irish Treaty

In March 1920 William Redmond a member of Parliament and combat veteran of World War I, addressed his fellow members of the British House of Commons concerning the Government of Ireland Act:

I was pleased to fight shoulder to shoulder, on the Somme and elsewhere, with my fellow-countrymen from the North of Ireland. We fraternised, and we thought that when we came home we would not bicker again, but that we would be happy in Ireland, with a Parliament for our own native country. We did not want two Irelands at the Front; it was one Ireland, whether we, came from the North or from the South...I feel in common with thousands of my countrymen in Ireland, that I and they have been cheated out of the fruits of our victory. We placed our trust in you and you have betrayed us.[87]

Michael Collins had negotiated the treaty and had it approved by the cabinet, the Dáil (on 7 January 1922 by 64–57), and by the people in national elections. Regardless of this, it was unacceptable to Éamon de Valera, who led the Irish Civil War to stop it. Collins was primarily responsible for drafting the constitution of the new Irish Free State, based on a commitment to democracy and rule by the majority.[88]

De Valera's minority refused to be bound by the result. Collins now became the dominant figure in Irish politics, leaving de Valera on the outside. The main dispute centred on the proposed status as a dominion (as represented by the Oath of Allegiance and Fidelity) for Southern Ireland, rather than as an independent all-Ireland republic, but continuing partition was a significant matter for Ulstermen like Seán MacEntee, who spoke strongly against partition or re-partition of any kind.[89] The pro-treaty side argued that the proposed Boundary Commission would give large swathes of Northern Ireland to the Free State, leaving the remaining territory too small to be viable.[90] In October 1922, the Irish Free State government established the North-Eastern Boundary Bureau (NEBB) a government office which by 1925 had prepared 56 boxes of files to argue its case for areas of Northern Ireland to be transferred to the Free State.[91]

De Valera had drafted his own preferred text of the treaty in December 1921, known as "Document No. 2". An "Addendum North East Ulster" indicates his acceptance of the 1920 partition for the time being, and of the rest of Treaty text as signed in regard to Northern Ireland:

That whilst refusing to admit the right of any part of Ireland to be excluded from the supreme authority of the Parliament of Ireland, or that the relations between the Parliament of Ireland and any subordinate legislature in Ireland can be a matter for treaty with a Government outside Ireland, nevertheless, in sincere regard for internal peace, and to make manifest our desire not to bring force or coercion to bear upon any substantial part of the province of Ulster, whose inhabitants may now be unwilling to accept the national authority, we are prepared to grant to that portion of Ulster which is defined as Northern Ireland in the British Government of Ireland Act of 1920, privileges and safeguards not less substantial than those provided for in the 'Articles of Agreement for a Treaty' between Great Britain and Ireland signed in London on 6 December 1921.[92]

Craig-Collins Pacts and Debate on Ulster Month

In early 1922 the two leaders of Northern and Southern Ireland agreed on two pacts that were referred to as the Craig-Collins Pacts. Both Pacts were designed to bring peace to Northern Ireland and deal with the issue of partition. Both Pacts fell apart and it was the last time for over 40 years that the leaders of government in the north and south were to meet. Among other issues, the first pact (21 January 1922) called for the ending of the ongoing "Belfast Boycott" of northern goods by the south and the return of jobs to the thousands of Catholics that had been forcibly removed from Belfast's mills and shipyards (see The Troubles in Northern Ireland (1920–1922).[93] The second Pact consisted of ten Articles which called for an end to all IRA activity in Northern Ireland and the setting up of a special police force that would represent the two communities. Article VII called for meetings before the Northern Ireland Government exercised its option to opt out of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The purpose of the meetings was to be "...whether means can be devised to secure the unity of Ireland or failing this whether agreement can be arrived at on the boundary question otherwise than by recourse to the Boundary Commission."[94]

Under the treaty it was provided that Northern Ireland would have a month – the "Ulster Month" – during which its Houses of Parliament could opt out of the Irish Free State. The Treaty was ambiguous on whether the month should run from the date the Anglo-Irish Treaty was ratified (in March 1922 via the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act) or the date that the Constitution of the Irish Free State was approved and the Free State established (6 December 1922).[95]

When the Irish Free State (Agreement) Bill was being debated on 21 March 1922, amendments were proposed which would have provided that the Ulster Month would run from the passing of the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act and not the Act that would establish the Irish Free State. Essentially, those who put down the amendments wished to bring forward the month during which Northern Ireland could exercise its right to opt out of the Irish Free State. They justified this view on the basis that if Northern Ireland could exercise its option to opt out at an earlier date, this would help to settle any state of anxiety or trouble on the new Irish border. Speaking in the House of Lords, the Marquess of Salisbury argued:[96]

The disorder [in Northern Ireland] is extreme. Surely the Government will not refuse to make a concession which will do something... to mitigate the feeling of irritation which exists on the Ulster side of the border.... [U]pon the passage of the Bill into law Ulster will be, technically, part of the Free State. No doubt the Free State will not be allowed, under the provisions of the Act, to exercise authority in Ulster; but, technically, Ulster will be part of the Free State.... Nothing will do more to intensify the feeling in Ulster than that she should be placed, even temporarily, under the Free State which she abominates.

The British Government took the view that the Ulster Month should run from the date the Irish Free State was established and not beforehand, Viscount Peel for the Government remarking:[95]

His Majesty's Government did not want to assume that it was certain that on the first opportunity Ulster would contract out. They did not wish to say that Ulster should have no opportunity of looking at entire Constitution of the Free State after it had been drawn up before she must decide whether she would or would not contract out.

Viscount Peel continued by saying the government desired that there should be no ambiguity and would to add a proviso to the Irish Free State (Agreement) Bill providing that the Ulster Month should run from the passing of the Act establishing the Irish Free State. He further noted that the Parliament of Southern Ireland had agreed with that interpretation, and that Arthur Griffith also wanted Northern Ireland to have a chance to see the Irish Free State Constitution before deciding.[95]

Lord Birkenhead remarked in the Lords debate:[96]

I should have thought, however strongly one may have embraced the cause of Ulster, that one would have resented it as an intolerable grievance if, before finally and irrevocably withdrawing from the Constitution, she was unable to see the Constitution from which she was withdrawing.

Northern Ireland opts out

The treaty "went through the motions of including Northern Ireland within the Irish Free State while offering it the provision to opt out".[97] It was certain that Northern Ireland would exercise its opt out. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Sir James Craig, speaking in the House of Commons of Northern Ireland in October 1922, said that "when the 6th of December is passed the month begins in which we will have to make the choice either to vote out or remain within the Free State." He said it was important that that choice be made as soon as possible after 6 December 1922 "in order that it may not go forth to the world that we had the slightest hesitation."[98] On 7 December 1922, the day after the establishment of the Irish Free State, the Parliament of Northern Ireland resolved to make the following address to the King so as to opt out of the Irish Free State:[99]

MOST GRACIOUS SOVEREIGN, We, your Majesty's most dutiful and loyal subjects, the Senators and Commons of Northern Ireland in Parliament assembled, having learnt of the passing of the Irish Free State Constitution Act, 1922 [...] do, by this humble Address, pray your Majesty that the powers of the Parliament and Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland.

Discussion in the Parliament of the address was short. No division or vote was requested on the address, which was described as the Constitution Act and was then approved by the Senate of Northern Ireland.[100] Craig left for London with the memorial embodying the address on the night boat that evening, 7 December 1922. King George V received it the following day.[101]

If the Houses of Parliament of Northern Ireland had not made such a declaration, under Article 14 of the Treaty, Northern Ireland, its Parliament and government would have continued in being but the Oireachtas would have had jurisdiction to legislate for Northern Ireland in matters not delegated to Northern Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act. This never came to pass. On 13 December 1922, Craig addressed the Parliament of Northern Ireland, informing them that the King had accepted the Parliament's address and had informed the British and Free State governments.[102]

Customs posts established

While the Irish Free State was established at the end of 1922, the Boundary Commission contemplated by the Treaty was not to meet until 1924. Things did not remain static during that gap. In April 1923, just four months after independence, the Irish Free State established customs barriers on the border. This was a significant step in consolidating the border. "While its final position was sidelined, its functional dimension was actually being underscored by the Free State with its imposition of a customs barrier".[103]

Boundary Commission

The Anglo-Irish Treaty (signed 6 December 1921) contained a provision (Article 12) that would establish a boundary commission, which would determine the border "...in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions...".[104] In October 1922 the Irish Free State government set up the North East Boundary Bureau to prepare its case for the Boundary Commission. The Bureau conducted extensive work but the commission refused to consider its work, which amounted to 56 boxes of files.[105] Most leaders in the Free State, both pro- and anti-treaty, assumed that the commission would award largely nationalist areas such as County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, South Londonderry, South Armagh and South Down and the City of Derry to the Free State and that the remnant of Northern Ireland would not be economically viable and would eventually opt for union with the rest of the island.

The terms of Article 12 were ambiguous – no timetable was established or method to determine "the wishes of the inhabitants". Article 12 did not specifically call for a plebiscite or specify a time for the convening of the commission (the commission did not meet until November 1924). The northern anti partitionist (and future Member of Parliament) Cahir Healy worked with the North East Boundary Bureau to develop cases for the exclusion of Nationalist areas from Northern Ireland. Healy urged the Dublin government to insist on a plebiscite in the counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone. By December 1924 the chairman of the commission (Richard Feetham) had firmly ruled out the use of plebiscites.[106] In Southern Ireland the new Parliament fiercely debated the terms of the Treaty yet devoted a very small amount of time on the issue of partition – just nine out of 338 transcript pages.[107] The commission's final report recommended only minor transfers of territory, and in both directions.

Make Up of the Commission

The commission consisted of only three members Justice Richard Feetham, who represented the British government. Feetham was a judge and graduate of Oxford. In 1923 Feetham was the legal advisor to the High Commissioner for South Africa.

Eoin MacNeill, the Irish governments Minister for Education, represented the Irish Government. In 1913 MacNeill established the Irish Volunteers and in 1916 issued countermanding orders instructing the Volunteers not to take part in the Easter Rising which greatly limited the numbers that turned out for the rising. On the day before his execution, the Rising leader Tom Clarke warned his wife about MacNeill: "I want you to see to it that our people know of his treachery to us. He must never be allowed back into the national life of this country, for so sure as he is, so sure he will act treacherously in a crisis. He is a weak man, but I know every effort will be made to whitewash him."[108]

Joseph R. Fisher was appointed by the British Government to represent the Northern Ireland Government (after the Northern Government refused to name a member). It has been argued that the selection of Fisher ensured that only minimal (if any) changes would occur to the existing border. In a 1923 conversation with the 1st Prime Minister of Northern Ireland James Craig, British Prime Minister Baldwin commented on the future makeup of the commission: "If the Commission should give away counties, then of course Ulster couldn't accept it and we should back her. But the Government will nominate a proper representative for Northern Ireland and we hope that he and Feetham will do what is right."[105] In September 1924 Winston Churchill made a speech (while out of political office) in which he made his feelings clear on the partition of Ireland: "On the one side will be Catholics, tending more and more to Republicanism; on the other Protestants, holding firmly to the British Empire and the Union Jack...No result could be more disastrous to Irish national aspirations..."[109]

A small team of five assisted the commission in its work. While Feetham was said to have kept his government contacts well informed on the commission's work, MacNeill consulted with no one.[110] With the leak of the Boundary Commission report (7 November 1925), MacNeill resigned from both the commission and the Free State Government. As he departed the Free State Government admitted that MacNeill "wasn't the most suitable person to be a commissioner."[111] The source of the leaked report was generally assumed to be made by Fisher. The commission's report was not published in full until 1969.[112]

War debt cancellation & final agreement

The Irish Free State, Northern Ireland and UK governments agreed to suppress the report and accept the status quo, while the UK government agreed that the Free State would no longer have to pay its share of the UK's national debt (the British claim was £157 million).[113][114] The Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill was quoted on the terms of the cancellation of the Irish war debt: "I made a substantial modification of the financial provisions."[115] Éamon de Valera commented on the cancellation of the southern governments debt (referred to as the war debt) to the British: the Free State "sold Ulster natives for four pound a head, to clear a debt we did not owe."[116]

The final agreement between the Irish Free State, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom (the inter-governmental Agreement) of 3 December 1925 was published later that day by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin.[117] The agreement was enacted by the "Ireland (Confirmation of Agreement) Act" and was passed unanimously by the British parliament on 8–9 December.[118] The Dáil voted to approve the agreement, by a supplementary act, on 10 December 1925 by a vote of 71 to 20.[119] With a separate agreement concluded by the three governments, the publication of Boundary Commission report became an irrelevance. Commission member Fisher stated to the Unionist leader Edward Carson that no area of importance had been ceded to the Irish Government: “If anybody had suggested twelve months ago that we could have kept so much I would have laughed at him”.[120] The President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State W. T. Cosgrave informed the Irish Parliament (the Dail) that "...the only security for the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland now depended on the goodwill of their neighbours."[121]

After partition

Both governments agreed to the disbandment of the Council of Ireland. The leaders of the two parts of Ireland did not meet again until 1965.[122] Since partition, Irish republicans and nationalists have sought to end partition, while Ulster loyalists and unionists have sought to maintain it. The pro-Treaty Cumann na nGaedheal government of the Free State hoped the Boundary Commission would make Northern Ireland too small to be viable. It focused on the need to build a strong state and accommodate Northern unionists.[123] The anti-Treaty Fianna Fáil had Irish unification as one of its core policies and sought to rewrite the Free State's constitution.[124] Sinn Féin rejected the legitimacy of the Free State's institutions altogether because it implied accepting partition.[125] In Northern Ireland, the Nationalist Party was the main political party in opposition to the Unionist governments and partition. Other early anti-partition groups included the National League of the North (formed in 1928), the Northern Council for Unity (formed in 1937) and the Irish Anti-Partition League (formed in 1945).[126] Until 1969 a system for elections known as plural voting was in place in Northern Ireland.[127] Plural voting allowed one person to vote multiple times in an election. Only ratepayers (or taxpayers) could vote in local elections and the House of Commons of Northern Ireland. Owners of businesses were often able to cast more than one vote while non ratepayers did not have the right to vote. In Southern Ireland plural voting for Dáil Éireann elections was abolished by the Electoral Act 1923.

Constitution of Ireland 1937

De Valera came to power in Dublin in 1932, and drafted a new Constitution of Ireland which in 1937 was adopted by plebiscite in the Irish Free State. Its articles 2 and 3 defined the 'national territory' as: "the whole island of Ireland, its islands and the territorial seas". The state was named 'Ireland' (in English) and 'Éire' (in Irish); a United Kingdom Act of 1938 described the state as "Eire". The irredentist texts in Articles 2 and 3 were deleted by the Nineteenth Amendment in 1998, as part of the Belfast Agreement.[128]

Sabotage Campaign of 1939–1940

In January 1939 the IRA's Army Council informed the British government that they were going to war with Britain with the goal of ending partition. The "Sabotage" or S-Plan took place only in England from January 1939 until May 1940. During this campaign approximately 300 bombings/acts of sabotage took place resulting in 10 deaths, 96 injuries and significant damage to infrastructure.[129] In response the British government enacted the Prevention of Violence Act 1939, which permitted deportation of persons thought to be associated with the IRA.[130] The Irish government enacted the Offences against the State Acts 1939–1998 with almost one thousand IRA members being imprisoned or interned without trial.[131]

British offer of unity in 1940

During the Second World War, after the Fall of France, Britain made a qualified offer of Irish unity in June 1940, without reference to those living in Northern Ireland. On their rejection, neither the London nor Dublin governments publicised the matter. Ireland would have allowed British ships to use selected ports for counter submarine operations, arresting Germans and Italians, setting up a joint defence council and allowing overflights. In return, arms would have been provided to Ireland and British forces would cooperate on a German invasion. London would have declared that it accepted 'the principle of a United Ireland' in the form of an undertaking 'that the Union is to become at an early date an accomplished fact from which there shall be no turning back.'[132] Clause ii of the offer promised a joint body to work out the practical and constitutional details, 'the purpose of the work being to establish at as early a date as possible the whole machinery of government of the Union'. On the day after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor (8 December 1941) Churchill sent a telegram to the Irish Prime Minister in which he obliquely offered Irish unity – "Now is your chance. Now or never! A nation once again! I will meet you wherever you wish." No meeting took place between the two prime ministers and there is no record of a response from de Valera.[133] The proposals were first published in 1970 in a biography of de Valera.[134]

1942–1973

In 1942–1944 the IRA carried out a series of attacks on security forces in Northern Ireland known as the Northern Campaign. The Irish government's internment of Irish Republicans in Curragh Camp greatly reduced the effectiveness of the IRA's campaign.[135]

In May 1949 the Taoiseach John A. Costello introduced a motion in the Dáil strongly against the terms of the UK's Ireland Act 1949 that confirmed partition for as long as a majority of the electorate in Northern Ireland wanted it, styled in Dublin as the "Unionist Veto".[136]

Congressman John E. Fogarty was the main mover of the Fogarty Resolution on 29 March 1950. This proposed suspending Marshall Plan Foreign Aid to the UK, as Northern Ireland was costing Britain $150,000,000 annually, and therefore American financial support for Britain was prolonging the partition of Ireland. Whenever partition was ended, Marshall Aid would restart. On 27 September 1951, Fogarty's resolution was defeated in Congress by 206 votes to 139, with 83 abstaining – a factor that swung some votes against his motion was that Ireland had remained neutral during World War II.[137]

From 1956 to 1962, the IRA carried out a limited guerrilla campaign in border areas of Northern Ireland, called the Border Campaign. It aimed to destabilise Northern Ireland and bring about an end to partition, but ended in failure.[138]

In 1965, Taoiseach Seán Lemass met Northern Ireland's Prime Minister Terence O'Neill. It was the first meeting between the two heads of government since partition.[139]

Both the Republic and the UK joined the European Economic Community in 1973.[140]

The Troubles and Good Friday Agreement

The Unionist governments of Northern Ireland were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority. A non-violent campaign to end discrimination began in the late 1960s. This civil rights campaign was opposed by loyalists and hard-line unionist parties, who accused it of being a republican front to bring about a united Ireland.[7] This unrest led to the August 1969 riots and the deployment of British troops, beginning a thirty-year conflict known as the Troubles (1969–98), involving republican and loyalist paramilitaries.[141][142] In 1973 a 'border poll' referendum was held in Northern Ireland on whether it should remain part of the UK or join a united Ireland. Irish nationalists boycotted the referendum and only 57% of the electorate voted, resulting in an overwhelming majority for remaining in the UK.[143]

The Northern Ireland peace process began in 1993, leading to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. It was ratified by two referendums in both parts of Ireland, including an acceptance that a united Ireland would only be achieved by peaceful means. The remaining provisions of the Government of Ireland Act 1920 were repealed and replaced in the UK by the Northern Ireland Act 1998 as a result of the Agreement. The Irish Free State (Consequential Provisions) Act 1922 had already amended the 1920 Act so that it would only apply to Northern Ireland. It was finally repealed in the Republic by the Statute Law Revision Act 2007.[144]

In its 2017 white paper on Brexit, the British government reiterated its commitment to the Agreement. On Northern Ireland's status, it said that the government's "clearly-stated preference is to retain Northern Ireland's current constitutional position: as part of the UK, but with strong links to Ireland".[145]

While not explicitly mentioned in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the Common Travel Area between the UK and the Republic of Ireland, EU integration at that time and the demilitarisation of the boundary region provided by the treaty resulted in the virtual dissolution of the border.[146]

Partition and sport

Following partition, most sporting bodies continued on an all-Ireland basis. The main exception was association football (soccer), as separate organising bodies were formed in Northern Ireland (Irish Football Association) and the Republic of Ireland (Football Association of Ireland).[147] At the Olympics, a person from Northern Ireland can choose to represent either the Republic of Ireland team (which competes as "Ireland") or United Kingdom team (which competes as "Great Britain").[148]

See also

References

- ↑ Jackson, Alvin (2010). Ireland 1798–1998: War, Peace and Beyond (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 239. ISBN 978-1444324150. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ Garvin, Tom: The Evolution of Irish Nationalist Politics : p. 143 Elections, Revolution and Civil War Gill & Macmillan (2005) ISBN 0-7171-3967-0

- 1 2 3 Lynch, Robert. The Partition of Ireland: 1918–1925. Cambridge University Press, 2019. pp. 11, 100–101

- ↑ Lynch (2019), p. 99

- 1 2 Lynch (2019), pp. 171–176

- ↑ Gibbons, Ivan (2015). The British Labour Party and the Establishment of the Irish Free State, 1918–1924. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 107. ISBN 978-1137444080. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- 1 2 Maney, Gregory. "The Paradox of Reform: The Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland", in Nonviolent Conflict and Civil Resistance. Emerald Group Publishing, 2012. p. 15

- ↑ Smith, Evan (20 July 2016). "Brexit and the history of policing the Irish border". History & Policy. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ Adam, Rudolf G. (2019). Brexit: Causes and Consequences. Springer. p. 142. ISBN 978-3-030-22225-3.

- ↑ Serhan, Yasmeen (10 April 2018). "The Good Friday Agreement in the Age of Brexit". The Atlantic. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ↑ Edgar Holt Protest in Arms Ch. III Orange Drums, pp. 32–33, Putnam London (1960)

- 1 2 Two home rule Bills Archived 2 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ↑ Bardon, Jonathan (1992). A History of Ulster. Blackstaff Press. p. 402. ISBN 0856404985.

- ↑ Maume, Patrick (1999). The long Gestation: Irish Nationalist Life 1891–1918. Gill and Macmillan. p. 10. ISBN 0-7171-2744-3.

- ↑ King, Carla (2000). "Defenders of the Union: Sir Horace Plunkett". In Boyce, D. George; O'Day, Alan (eds.). Defenders of the Union: A Survey of British and Irish Unionism Since 1801. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 1134687435.

- 1 2 James F. Lydon, The Making of Ireland: From Ancient Times to the Present Archived 8 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge, 1998, p. 326

- ↑ O'Day, Alan. Irish Home Rule, 1867–1921. Manchester University Press, 1998. p. 247

- ↑ O'Day, p. 252

- ↑ O'Day, p. 254

- ↑ O'Brien, Jack (1989). British Brutality in Ireland. Dublin: The Mercier Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-85342-879-4.

- ↑ Stewart, A.T.Q., The Ulster Crisis, Resistance to Home Rule, 1912–14, pp. 58–68, Faber and Faber (1967) ISBN 0-571-08066-9

- ↑ Annie Ryan, Witnesses: Inside the Easter Rising, Liberties Press, 2005, p. 12

- ↑ Collins, M. E., Sovereignty and partition, 1912–1949, pp. 32–33, Edco Publishing (2004) ISBN 1-84536-040-0

- ↑ Mulvagh, Conor (24 May 2021). "Plotting partition: The other Border options that might have changed Irish history". The Irish Times. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Holmes, Richard (2004). The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 178–89. ISBN 0-297-84614-0.

- ↑ Holmes, Richard (2004). The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 168. ISBN 0-297-84614-0.

- ↑ Bromage, Mary (1964), Churchill and Ireland, University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, IL, pg 37., Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 64-20844

- ↑ Jackson, Alvin. Home Rule: An Irish History, 1800–2000. pp. 137–138

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 161–163

- ↑ Hennessey, Thomas: Dividing Ireland, World War I and Partition, "The passing of the Home Rule Bill" p. 76, Routledge Press (1998) ISBN 0-415-17420-1

- ↑ Jackson, Alvin: p. 164

- ↑ Coleman, Marie (2013). The Irish Revolution, 1916–1923. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-1317801474. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ Lyons, F.S.L. (1996). "The new nationalism, 1916–18". In Vaughn, W.E. (ed.). A New History of Ireland: Ireland under the Union, II, 1870–1921. Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780198217510. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ Hachey, Thomas E. (2010). The Irish Experience Since 1800: A Concise History. M.E. Sharpe. p. 133. ISBN 9780765628435. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ R.J.Q. Adams & Philip Poirier. The Conscription Controversy in Great Britain. Springer, 1987. p. 239

- ↑ Coleman (2013), p. 39

- ↑ Lynch (2019), p. 48

- ↑ Lynch (2019), pp. 51–52

- ↑ Mitchell, Arthur. Revolutionary Government in Ireland. Gill & MacMillan, 1995. p. 245

- ↑ Coleman, Marie (2013). The Irish Revolution, 1916–1923. Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 978-1317801474.

- ↑ Gibney, John (editor). The Irish War of Independence and Civil War. Pen and Sword History, 2020. pp.xii–xiii

- ↑ Moore, Cormac, (2019), Birth of the Border, Merrion Press, Newbridge, pg 17, ISBN 9781785372933

- 1 2 Moore, pg 19

- ↑ Fanning, R, (2013), Fatal Path: British Government and the Irish Revolution 1910–1922, Faber & Faber, London, pg 104

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 227–229

- ↑ Fanning, pg 212

- ↑ Jackson, p. 230

- ↑ The Irish Election of 1918 Archived 24 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. ARK. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ↑ Morland, Paul. Demographic Engineering: Population Strategies in Ethnic Conflict. Routledge, 2016. pp.96–98

- ↑ Farrell, Michael, (1980), Northern Ireland the Orange State, Pluto Press Ltd, London, pg. 24, ISBN 0 86104 300 6

- ↑ Craig, Charles (29 March 1920). MP (PDF) (Speech). House of Commons: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI). Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Parliamentary Election Results 1921–29: Counties". Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ Phoenix, Eamon (1994), Northern nationalism: nationalist politics, partition and the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland 1890–1940, Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast, Pg 146, ISBN 9780901905550

- ↑ McCluskey, Fergal, (2013), The Irish Revolution 1912–23: Tyrone, Four Courts Press, Dublin, pg 105, ISBN 9781846822995

- ↑ Farrell, pg 82, Phoenix (1994), pg 163.

- ↑ Lynch, Robert. Revolutionary Ireland: 1912–25. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015. pp. 97–98

- ↑ "1920 local government elections recalled in new publication" Archived 31 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Irish News, 19 October 2020.

- ↑ Lynch (2019), pp. 90–92

- ↑ Lynch (2019), pp. 92–93

- ↑ Lawlor, Pearse. The Burnings, 1920. Mercier Press, 2009. pp. 90–92

- ↑ Lawlor, The Burnings, 1920, p. 184

- ↑ Farrell, Michael. Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Pluto Press, 1983. p.166

- ↑ Lynch (2019), p.99

- ↑ Joseph Lee, Ireland 1912–1985: Politics and society, p. 43

- 1 2 O'Day, Alan. Irish Home Rule, 1867–1921. Manchester University Press, 1998. p. 299

- ↑ Jackson, Alvin. Home Rule – An Irish History. Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 368–370

- ↑ O'Day, p. 300

- ↑ Ward, Alan J (1994). The Irish Constitutional Tradition. Responsible Government and Modern Ireland 1782–1922. Catholic University Press of America. pp. 103–110. ISBN 0-8132-0793-2.

- ↑ PRESIDENT'S STATEMENT Archived 13 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 1–10 May 1921

- ↑ No. 133UCDA P150/1902 Archived 23 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine De Valera to Lord Justice O'Connor, 4 July 1921

- ↑ Moore, pg 84.

- ↑ Lee, J.J.: Ireland 1912–1985 Politics and Society, p. 47, Cambridge University Press (1989, 1990) ISBN 978-0-521-37741-6

- 1 2 "Correspondence between Lloyd-George and De Valera, June–September 1921". Ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ Devlin, Joseph (11 November 1920). Government of Ireland Bill (Speech). debate. UK House of Parliament: Hansard. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ Moore, pg 22.

- ↑ Bromage, pg 63.

- ↑ Moore, pg 58.

- ↑ The Times, Court Circular, Buckingham Palace, 6 December 1922.

- ↑ "New York Times, 6 December 1922" (PDF). The New York Times. 7 December 1922. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ For further discussion, see: Dáil Éireann – Volume 7 – 20 June 1924 The Boundary Question – Debate Resumed Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ legally, under Article 12 of the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922

- ↑ Morgan, Austen (2000). The Belfast Agreement: A Practical Legal Analysis (PDF). The Belfast Press. pp. 66, 68. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ Morgan (2000), p. 68

- ↑ Lynch (2019), pp.197–199

- ↑ "Ashburton Guardian, Volume XLII, Issue 9413, 16 December 1921, Page 5". Paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. 16 December 1921. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ "IRELAND IN 1921 by C. J. C. Street O.B.E., M.C". Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ "GOVERNMENT OF IRELAND BILL". HANSARD. UK parliament. 29 March 1920. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ↑ Tim Pat Coogan, The Man Who Made Ireland: The Life and Death of Michael Collins. (Palgrave Macmillan, 1992) p 312.

- ↑ "Dáil Éireann – Volume 3 – 22 December, 1921 DEBATE ON TREATY". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ Knirck, Jason. Imagining Ireland's Independence: The Debates Over the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. Rowman & Littlefield, 2006. p.104

- ↑ Crowley, John (2017), Atlas of the Irish Revolution, New York University Press, New York, pg 830, ISBN 978-1479834280

- ↑ "Document No. 2" text; viewed online January 2011 Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine; original held at the National Archives of Ireland in file DE 4/5/13.

- ↑ McDermott, Jim (2001), Northern Divisions, BTP Publications, Belfast, pgs. 159–160, ISBN 1-900960-1-1-7

- ↑ McDermott, pg. 197.

- 1 2 3 The Times, 22 March 1922

- 1 2 "HL Deb 27 March 1922 vol 49 cc893-912 IRISH FREE STATE (AGREEMENT) BILL". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 27 March 1922. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ 'The Irish Border: History, Politics, Culture' Malcolm Anderson, Eberhard Bort (Eds.) pg. 68

- ↑ Northern Ireland Parliamentary Debates, 27 October 1922

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Parliamentary Report, 7 December 1922". Stormontpapers.ahds.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ↑ "Northern Irish parliamentary reports, online; Vol. 2 (1922), pages 1147–1150". Ahds.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ The Times, 9 December 1922

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Parliamentary Report, 13 December 1922, Volume 2 (1922) / Pages 1191–1192, 13 December 1922". Stormontpapers.ahds.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ↑ MFPP Working Paper No. 2, "The Creation and Consolidation of the Irish Border" by KJ Rankin and published in association with Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin and Institute for Governance, Queen's University, Belfast (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 48)

- ↑ Moore, p. 63

- 1 2 Moore, pg. 79

- ↑ Phoenix, Eamon & Parkinson, Alan (2010), Conflicts in the North of Ireland, 1900–2000, Four Courts Press, Dublin, Pg 145, ISBN 978 1 84682 189 9

- ↑ Moore, pgs 63–64.

- ↑ Clarke, Kathleen (2008), Revolutionary Woman, Dublin: The O'Brien Press p. 94, ISBN 978-1-84717-059-0.

- ↑ Bromage, pgs 105-106.

- ↑ MacEoin, Uinseann (1997), The IRA in the Twilight Years: 1923–1948, Dublin: Argenta. p. 34, ISBN 9780951117248.

- ↑ O'Beachain, D, (2019), From Partition to Brexit: The Irish Government and Northern Ireland, Manchester University Press, Manchester, pg 26.

- ↑ "The Boundary Commission Debacle 1925, aftermath & implications". History Ireland. 1996. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ "Joseph Brennan's financial memo of 30 November 1925". Difp.ie. 30 November 1925. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ↑ Lee, Joseph. Ireland, 1912–1985: Politics and Society. Cambridge University Press, 1989. p.145

- ↑ Bromage, pg 106.

- ↑ McCluskey, pg 133

- ↑ "Announcement of agreement, Hansard 3 Dec 1925". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 3 December 1925. Archived from the original on 15 July 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ↑ "Hansard; Commons, 2nd and 3rd readings, 8 Dec 1925". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 8 December 1925. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ "Dáil vote to approve the Boundary Commission negotiations". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ↑ Clifton, Nick (December 2020). "A Commission Steeped in Controversy?". Epoch. 02: EPOCH Magazine. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Ferriter, D (2004), The Transformation of Ireland, The Overlook Press, Woodstock, NY, pg 294. ISBN 1-86197-307-1

- ↑ Moore, pg 81.

- ↑ Farrell, Mel. Party Politics in a New Democracy: The Irish Free State, 1922–37. Springer, 2017. pp.136–137

- ↑ Farrell (2017), pp.152–153

- ↑ Prager, Jeffrey. Building Democracy in Ireland: Political Order and Cultural Integration in a Newly Independent Nation. Cambridge University Press, 1986. p.139

- ↑ Peter Barberis, John McHugh, Mike Tyldesley (editors). Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organizations. A&C Black, 2000. pp.236–237

- ↑ "Electoral Law Act (Northern Ireland) 1968". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ↑ Albert, Cornelia. The Peacebuilding Elements of the Belfast Agreement and the Transformation of the Northern Ireland Conflict. Peter Lang, 2009. pp.50–51

- ↑ McKenna, Joseph (2016), The IRA Bombing Campaign Against Britain, 1939-40. Jefferson, NC US: McFarland & Company Publishers. p. 138.

- ↑ McKenna, p. 79.

- ↑ Crowley, John (2017), Atlas of the Irish Revolution, New York University Press, New York, pg 809, ISBN 978-1479834280

- ↑ Eds. O'Day A. & Stevenson J., Irish Historical Documents since 1800 (Gill & Macmillan, Dublin 1992) p. 201. ISBN 0-7171-1839-8

- ↑ Bromage, pg 162.

- ↑ Longford, Earl of & O'Neill, T.P. Éamon de Valera (Hutchinson 1970; Arrow paperback 1974) Arrow pp. 365–368. ISBN 0-09-909520-3

- ↑ Bell, J. Bower (2004). The Secret Army: The IRA. New Brunswick, USA: Transactions Publishers. p. 229. ISBN 1-56000-901-2

- ↑ "Dáil Éireann – Volume 115 – 10 May 1949 – Protest Against Partition—Motion". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ↑ Grimes, J. S., From Bricklayer to Bricklayer: The Rhode Island Roots of Congressman John E. Fogarty's Irish-American Nationalism (Providence College, Rhode Island, 1990), p. 7.

- ↑ English, Richard. Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA. Pan Macmillan, 2008. pp.72–74

- ↑ "Lemass-O'Neill talks focused on `purely practical matters'" Archived 25 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Irish Times, 2 January 1998.

- ↑ Ingraham, Jeson. The European Union and Relationships Within Ireland Archived 12 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ↑ Coogan, Tim Pat. The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. p.106

- ↑ Tonge, Jonathan. Northern Ireland. Polity Press, 2006. pp.153, 156–158

- ↑ Chronology of the Conflict: 1973 Archived 18 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ↑ A nation once again? The Government of Ireland Act Archived 2 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Gazette of the Law Society of Ireland. 4 September 2020.

- ↑ HM Government The United Kingdom's exit from and new partnership with the European Union; Cm 9417, February 2017

- ↑ Barry, Sinead (21 August 2019). "The Good Friday Agreement, the Irish backstop and Brexit | #TheCube". euronews. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ↑ Philip Waller, Robert Peberdy (editors). A Dictionary of British and Irish History. Wiley, 2020. p. 598

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Patrick T. (Spring 1998). "Ireland & the Olympic Games". History Ireland. Dublin. 6 (1). Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

Further reading

- Denis Gwynn, The History of Partition (1912–1925). Dublin: Browne and Nolan, 1950.

- Michael Laffan, The Partition of Ireland 1911–25. Dublin: Dublin Historical Association, 1983.

- Thomas G. Fraser, Partition in Ireland, India and Palestine: theory and practice.London: Macmillan, 1984.

- Clare O'Halloran, Partition and the limits of Irish nationalism: an ideology under stress. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1987.

- Austen Morgan, Labour and partition: the Belfast working class, 1905–1923. London: Pluto, 1991.

- Eamon Phoenix, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist politics, partition and the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 1994.

- Thomas Hennessey, Dividing Ireland: World War 1 and partition. London: Routledge, 1998.

- John Coakley, Ethnic conflict and the two-state solution: the Irish experience of partition. Dublin: Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin, 2004.

- Benedict Kiely, Counties of Contention: a study of the origins and implications of the partition of Ireland. Cork: Mercier Press, 2004.

- Brendan O'Leary, Analysing partition: definition, classification and explanation. Dublin: Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin, 2006

- Brendan O'Leary, Debating Partition: Justifications and Critiques. Dublin: Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin, 2006.

- Robert Lynch, Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2006.

- Robert Lynch, The Partition of Ireland: 1918–1925. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Margaret O'Callaghan, Genealogies of partition: history, history-writing and the troubles in Ireland. London: Frank Cass; 2006.

- Lillian Laila Vasi, Post-partition limbo states: failed state formation and conflicts in Northern Ireland and Jammu-and-Kashmir. Koln: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2009.

- Stephen Kelly, Fianna Fáil, Partition and Northern Ireland, 1926 – 1971. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2013

External links

- The Partition of Ireland (Workers Solidarity Movement – An anarchist organisation which supports the IRA)

- James Connolly: Labour and the Proposed Partition of Ireland (Marxists Internet Archive)

- The Socialist Environmental Alliance: The SWP and Partition of Ireland (The Blanket)

- Sean O Mearthaile, Partition — what it means for Irish workers (The ETEXT Archives)

- Northern Ireland Timeline: Partition: Civil war 1922–1923 (BBC History). Archived 7 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- Home rule for Ireland, Scotland and Wales (LSE Library). Archived 10 August 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- Towards a Lasting Peace in Ireland (Sinn Féin)

- History of the Republic of Ireland (History World)