Reconstructive memory is a theory of memory recall, in which the act of remembering is influenced by various other cognitive processes including perception, imagination, motivation, semantic memory and beliefs, amongst others. People view their memories as being a coherent and truthful account of episodic memory and believe that their perspective is free from an error during recall. However, the reconstructive process of memory recall is subject to distortion by other intervening cognitive functions such as individual perceptions, social influences, and world knowledge, all of which can lead to errors during reconstruction.

Reconstructive process

Memory rarely relies on a literal recount of past experiences. By using multiple interdependent cognitive processes, there is never a single location in the brain where a given complete memory trace of experience is stored.[1] Rather, memory is dependent on constructive processes during encoding that may introduce errors or distortions. Essentially, the constructive memory process functions by encoding the patterns of perceived physical characteristics, as well as the interpretive conceptual and semantic functions that act in response to the incoming information.[2]

In this manner, the various features of the experience must be joined together to form a coherent representation of the episode.[3] If this binding process fails, it can result in memory errors. The complexity required for reconstructing some episodes is quite demanding and can result in incorrect or incomplete recall.[4] This complexity leaves individuals susceptible to phenomena such as the misinformation effect across subsequent recollections.[5] By employing reconstructive processes, individuals supplement other aspects of available personal knowledge and schema into the gaps found in episodic memory in order to provide a fuller and more coherent version, albeit one that is often distorted.[6]

Many errors can occur when attempting to retrieve a specific episode. First, the retrieval cues used to initiate the search for a specific episode may be too similar to other experiential memories and the retrieval process may fail if the individual is unable to form a specific description of the unique characteristics of the given memory they would like to retrieve.[7] When there is little available distinctive information for a given episode there will be more overlap across multiple episodes, leading the individual to recall only the general similarities common to these memories. Ultimately proper recall for a desired target memory fails due to the interference of non-target memories that are activated because of their similarity.[3]

Secondly, a large number of errors that occur during memory reconstruction are caused by faults in the criterion-setting and decision making processes used to direct attention towards retrieving a specific target memory. When there are lapses in the recall of aspects of episodic memory, the individual tends to supplement other aspects of knowledge that are unrelated to the actual episode to form a more cohesive and well-rounded reconstruction of the memory, regardless of whether or not the individual is aware of such supplemental processing. This process is known as confabulation. All of the supplemental processes occurring during the course of reconstruction rely on the use of schema, information networks that organize and store abstract knowledge in the brain.

Characteristics

Schema

Schema are generally defined as mental information networks that represent some aspect of collected world knowledge. Frederic Bartlett was one of the first psychologists to propose Schematic theory, suggesting that the individual's understanding of the world is influenced by elaborate neural networks that organize abstract information and concepts.[8] Schema are fairly consistent and become strongly internalized in the individual through socialization, which in turn alters the recall of episodic memory. Schema is understood to be central to reconstruction, used to confabulate, and fill in gaps to provide a plausible narrative. Bartlett also showed that schema can be tied to cultural and social norms.[9]

Jean Piaget's theory of schema

Piaget's theory proposed an alternative understanding of schema based on the two concepts: assimilation and accommodation. Piaget defined assimilation as the process of making sense of the novel and unfamiliar information by using previously learned information. To assimilate, Piaget defined a second cognitive process that served to integrate new information into memory by altering preexisting schematic networks to fit novel concepts, what he referred to as accommodation.[10] For Piaget, these two processes, accommodation, and assimilation, are mutually reliant on one another and are vital requirements for people to form basic conceptual networks around world knowledge and to add onto these structures by utilizing preexisting learning to understand new information, respectively.

According to Piaget, schematic knowledge organizes features information in such a way that more similar features are grouped so that when activated during recall the more strongly related aspects of memory will be more likely to activate together. An extension of this theory, Piaget proposed that the schematic frameworks that are more frequently activated will become more strongly consolidated and thus quicker and more efficient to activate later.[11]

Frederic Bartlett's experiments

Frederic Bartlett originally tested his idea of the reconstructive nature of recall by presenting a group of participants with foreign folk tales (his most famous being "War of the Ghosts"[12]) with which they had no previous experience. After presenting the story, he tested their ability to recall and summarize the stories at various points after the presentation to newer generations of participants. His findings showed that the participants could provide a simple summary but had difficulty recalling the story accurately, with the participants' own account generally being shorter and manipulated in such a way that aspects of the original story that were unfamiliar or conflicting to the participants' own schematic knowledge were removed or altered in a way to fit into more personally relevant versions.[8] For instance, allusions made to magic and Native American mysticism that were in the original version were omitted as they failed to fit into the average Westerner schematic network. Besides, after several recounts of the story had been made by successive generations of participants, certain aspects of the recalled tale were embellished so they were more consistent with the participants' cultural and historical viewpoint compared to the original text (e.g. Emphasis placed on one of the characters desire to return to care for his dependent elderly mother). These findings lead Bartlett to conclude that recall is predominately a reconstructive rather than reproductive process.[9]

James J. Gibson built off of the work that Bartlett originally laid down, suggesting that the degree of change found in a reproduction of an episodic memory depends on how that memory is later perceived.[13] This concept was later tested by Carmichael, Hogan, and Walter (1932) who exposed a group of participants to a series of simple figures and provided different words to describe each images. For example, all participants were exposed to an image of two circles attached by a single line, where some of the participants were told it was a barbell and the rest were told it was a pair of reading glasses. The experiment revealed that when the participants were later tasked with replicating the images, they tended to add features to their own reproduction that more closely resembled the word they were primed with.

Confirmation bias

During retrieval of episodic memories, people use their schematic knowledge to fill in information gaps, though they generally do so in a manner that implements aspects of their own beliefs, moral values, and personal perspective that leads the reproduced memory to be a biased interpretation of the original version. Confirmation bias results in overconfidence in personal perception and usually leads to a strengthening of beliefs, often in the face of contradictory dis-confirming evidence.[14]

Associated neural activity

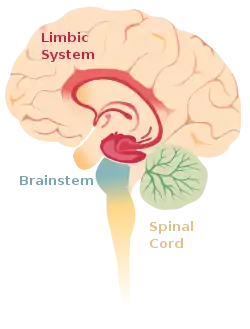

Recent research using neuro-imaging technology including PET and fMRI scanning has shown that there is an extensive amount of distributed brain activation during the process of episodic encoding and retrieval. Among the various regions, the two most active areas during the constructive processes are the medial temporal lobe (including the hippocampus) and the prefrontal cortex.[15] The Medial Temporal lobe is especially vital for encoding novel events in episodic networks, with the Hippocampus acting as one of the central locations that acts to both combine and later separate the various features of an event.[16][17] Most popular research holds that the Hippocampus becomes less important in long term memory functioning after more extensive consolidation of the distinct features present at the time of episode encoding has occurred. In this way long term episodic functioning moves away from the CA3 region of the Hippocampal formation into the neocortex, effectively freeing up the CA3 area for more initial processing.[17] Studies have also consistently linked the activity of the Prefrontal Cortex, especially that which occurs in the right hemisphere, to the process of retrieval.[18] The Prefrontal cortex appears to be utilized for executive functioning primarily for directing the focus of attention during retrieval processing, as well as for setting the appropriate criterion required to find the desired target memory.[15]

Applications

Eyewitness testimony

Eyewitness testimony is a commonly recurring topic in the discussion of reconstructive memory and its accuracy is the subject of many studies. Eyewitness testimony is any firsthand accounts given by individuals of an event they have witnessed. Eyewitness testimony is used to acquire details about the event and even to identify the perpetrators of the event.[19] Eyewitness testimony is used often in court and is viewed favorably by juries as a reliable source of information.[19] Unfortunately, eyewitness testimony can be easily manipulated by a variety of factors such as:

- Anxiety and stress

- Schema

- The cross-race effect

Anxiety and stress

Anxiety is a state of distress or uneasiness of mind caused by fear[20] and it is a consistently associated with witnessing crimes. In a study done by Yuille and Cutshall (1986), they discovered that witnesses of real-life violent crimes were able to remember the event quite vividly even five months after it originally occurred.[19] In fact, witnesses to violent or traumatic crimes often self-report the memory as being particularly vivid. For this reason, eyewitness memory is often listed as an example of flashbulb memory.

However, in a study by Clifford and Scott (1978), participants were shown either a film of a violent crime or a film of a non-violent crime. The participants who viewed the stressful film had difficulty remembering details about the event compared to the participants that watched the non-violent film.[19] In a study by Brigham et al. (2010), subjects who experienced an electrical shock were less accurate in facial recognition tests, suggesting that some details were not well remembered under stressful situations.[21] In fact, in the case of the phenomena known as weapon focus, eyewitnesses to stressful crimes involving weapons may perform worse during suspect identification.[22]

Further studies on flashbulb memories seem to indicate that witnesses may recall vivid sensory content unrelated to the actual event but which enhance its perceived vividness.[23] Due to this vividness, eyewitnesses may place higher confidence in their reconstructed memories.[24]

Application of schema

The use of schemas has been shown to increase the accuracy of recall of schema-consistent information but this comes at the cost of decreased recall of schema-inconsistent information. A study by Tuckey and Brewer[25] found that after 12 weeks, memories of information inconsistent with a schema-typical robbery decays much faster than those that are schema-consistent. These were memories such as the method of getaway, demands by the robbers, and the robbers' physical appearance. The study also found that information that was schema-inconsistent but stood out as very abnormal for the participants was usually recalled more readily and was retained for the duration of the study. The authors of the study advise that interviewers of eyewitnesses should take note of such reports because there is a possibility that they may be accurate.

Cross-race effect

Reconstructing the face of another race requires the use of schemas that may not be as developed and refined as those of the same race.[26] The cross-race effect is the tendency that people have to distinguish among other of their race than of other races. Although the exact cause of the effect is unknown, two main theories are supported. The perceptual expertise hypothesis postulates that because most people are raised and are more likely to associate with others of the same race, they develop an expertise in identifying the faces of that race. The other main theory is the in-group advantage. It has been shown in the lab that people are better at discriminating the emotions of in-group members than those of out-groups.[27]

Leading questions

Often during eyewitness testimonies, the witness is interrogated about their particular view of an incident and often the interrogator will use leading questions to direct and control the type of response that is elicited by the witness.[28] This phenomenon occurs when the response a person gives can be persuaded by the way a question is worded. For example, a person could be posed a question in two different forms:

- "What was the approximate height of the robber?" which would lead the respondent to estimate the height according to their original perceptions. They could alternatively be asked:

- "How short was the robber?" which would persuade the respondent to recall that the robber was actually shorter than they had originally perceived.

Using this method of controlled interrogation, the direction of a witness cross-examination can often be controlled and manipulated by the individual who is posing questions to fit their own needs and intentions.

Retrieval cues

After the information is encoded and stored in our memory, specific cues are often needed to retrieve these memories. These are known as retrieval cues and they play a major role in reconstructive memory. The use of retrieval cues can both promote the accuracy of reconstructive memory as well as detract from it. The most common aspect of retrieval cues associated with reconstructive memory is the process that involves recollection. This process uses logical structures, partial memories, narratives, or clues to retrieve the desired memory.[29] However, the process of recollection is not always successful due to cue-dependent forgetting and priming.

Cue-dependent forgetting

Cue-dependent forgetting (also known as retrieval failure) occurs when memories are not obtainable because the appropriate cues are absent.[30] This is associated with a relatively common occurrence known as the tip of the tongue (TOT) phenomenon, originally developed by the psychologist William James. Tip of the tongue phenomenon refers to when an individual knows particular information, and they are aware that they know this information, yet can not produce it even though they may know certain aspects about the information.[31] For example, during an exam a student is asked who theorized the concept of Psychosexual Development, the student may be able to recall the details about the actual theory but they are unable to retrieve the memory associated with who originally introduced the theory.

Priming

Priming refers to an increased sensitivity to certain stimuli due to prior experience.[32] Priming is believed to occur outside of conscious awareness, which makes it different from memory that relies on the direct retrieval of information.[33] Priming can influence reconstructive memory because it can interfere with retrieval cues. Psychologist Elizabeth Loftus presented many papers concerning the effects of proactive interference on the recall of eyewitness events. Interference involving priming was established in her classic study with John Palmer in 1974.[34] Loftus and Palmer recruited 150 participants and showed each of them a film of a traffic accident. After, they had the participants fill out a questionnaire concerning the video's details. The participants were split into three groups:

- Group A contained 50 participants that were asked: "About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?”

- Group B contained 50 participants that were asked: "About how fast were the cars going when they smashed each other?"

- Group C contained 50 participants and were not asked this question because they were meant to represent a control group

A week later, all of the participants were asked whether or not there had been any broken glass in the video. A statistically significant number of participants in the group B answered that they remembered seeing broken glass in the video (p < -.05). However, there was not any broken glass in the video. The difference between this group and the others was that they were primed with the word “smashed” in the questionnaire, one week before answering the question. By changing one word in the questionnaire, their memories were re-encoded with new details.[35]

Reconstructive errors

Confabulation

Confabulation is the involuntary false remembering of events and can be a characteristic of several psychological diseases such as Korsakoff's syndrome, Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia and traumatic injury of certain brain structures.[36] Those confabulating don't know that what they are remembering is false and have no intent to deceive.[37]

In the regular process of reconstruction, several sources are used to accrue information and add detail to memory. For patients producing confabulations, some key sources of information are missing and so other sources are used to produce a cohesive, internally consistent, and often believable false memory.[38] The source and type of confabulations differ for each type of disease or area of traumatic damage.

Selective memory

Selective memory involves actively forgetting negative experiences or enhancing positive ones.[39] This process actively affects reconstructive memory by distorting recollections of events. This affects reconstructive memories in two ways:

- by preventing memories from being recalled, even when appropriate cues are present

- by enhancing one's own role in previous experiences, also known as motivated self-enhancement

Many autobiographies are excellent examples of motivated self-enhancement because when recalling the events that have taken place in one's life, there is a tendency to make oneself appear to be more involved in positive experiences, though others may remember the event differently.

See also

References

- ↑ Squire, LR (1992). "Memory and the hippocampus: a synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans" (PDF). Psychol. Rev. 99 (2): 195–231. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.195. PMID 1594723.

- ↑ Schacter DL. 1989. Memory. In Foundations of Cognitive Science, ed. MI Posner, pp. 683–725. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

- 1 2 Hemmer, Pernille; Steyvers, Mark (2009). "A Bayesian Account of Reconstructive Memory". Topics in Cognitive Science. 1 (1): 189–202. doi:10.1111/j.1756-8765.2008.01010.x. ISSN 1756-8765. PMID 25164805.

- ↑ Torres-Trejo, Frine; Cansino, Selene (2016-06-30). "The Effects of the Amount of Information on Episodic Memory Binding". Advances in Cognitive Psychology. 12 (2): 79–87. doi:10.5709/acp-0188-z. ISSN 1895-1171. PMC 4975570. PMID 27512526.

- ↑ Kiat, John E.; Belli, Robert F. (2017-05-01). "An exploratory high-density EEG investigation of the misinformation effect: Attentional and recollective differences between true and false perceptual memories". Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 141: 199–208. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2017.04.007. ISSN 1074-7427. PMID 28442391. S2CID 4421445.

- ↑ Frisoni, Matteo; Di Ghionno, Monica; Guidotti, Roberto; Tosoni, Annalisa; Sestieri, Carlo (2021). "Reconstructive Nature of Temporal Memory for Movie Scenes". Cognition. 208: 104557. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104557. ISSN 0010-0277. PMID 33373938. S2CID 229539467.

- ↑ Burgess, PW; Shallice, T (1996). "Confabulation and the control of recollection". Memory. 4 (4): 359–411. doi:10.1080/096582196388906. PMID 8817460.

- 1 2 ""Frederick Bartlett", Some Experiments on the Reproduction of Folk-Stories, March 30, 1920" (PDF).

- 1 2 Bartlett, Sir Frederic Charles; Bartlett, Frederic C.; Bartlett, Frederic Charles (1995-06-30). Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48356-8.

- ↑ Jack Block (1982). "Assimilation, Accommodation, and the Dynamics of Personality Development" (PDF). Child Development. 53 (2): 281–295. doi:10.2307/1128971. JSTOR 1128971.

- ↑ Auger, W.F. & Rich, S.J. (2006.) Curriculum Theory and Methods: Perspectives on Learning and Teaching. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ ""War of the Ghosts", March 5, 2012". Archived from the original on October 8, 2001. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ Gibson, J.J. (1929). "The Reproduction of Visually Perceived Forms" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology. 12 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1037/h0072470.

- ↑ Plous, S. 1993. The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making. McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-050477-6, OCLC 26931106

- 1 2 Schacter, DL; Norman, KA; Koutstaal, W (1998). "The Cognitive Neuroscience of Constructive Memory". Annual Review of Psychology. 49: 289–318. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.289. PMID 9496626. S2CID 5141113.

- ↑ Tulving, E; Markowitsch, H.J.; Kapur, S; Habib, R; Houle, S. (1994). "Novelty encoding networks in the human brain: positron emission tomography data". NeuroReport. 5 (18): 2525–28. doi:10.1097/00001756-199412000-00030. PMID 7696595.

- 1 2 McClelland JL, McNaughton BL, O’Reilly RC. 1995. Why There Are Complementary Learning Systems in the Hippocampus and Neocortex: Insights from the Successes and Failures of Connectionist Models of Learning and Memory. Psychology Review 102:419–57

- ↑ Tulving, E; Kapur, S; Markowitsch, HJ; Craik, FIM; Habib, R; et al. (1994). "Neuroanatomical Correlates of Retrieval in Episodic Memory: Auditory Sentence Recognition". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 91 (6): 2012–15. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.2012T. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.6.2012. PMC 43299. PMID 8134341.

- 1 2 3 4 McLeod, S. (October 13, 2009). "Eyewitness Testimony - Simply Psychology". Simply Psychology.

- ↑ "Anxiety - Define Anxiety at Dictionary.com".

- ↑ Brigham, John C.; Maass, Anne; Martinez, David; Whittenberger, Gary (1983-09-01). "The Effect of Arousal on Facial Recognition". Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 4 (3): 279–293. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0403_6. ISSN 0197-3533.

- ↑ Fawcett, Jonathan M.; Peace, Kristine A.; Greve, Andrea (2016-09-01). "Looking Down the Barrel of a Gun: What Do We Know About the Weapon Focus Effect?". Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. 5 (3): 257–263. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2016.07.005. ISSN 2211-3681.

- ↑ Howes, Mary; O'Shea, Geoffrey (2014-01-01), Howes, Mary; O'Shea, Geoffrey (eds.), "Chapter 9 - Memory and Emotion", Human Memory, Academic Press, pp. 177–196, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-408087-4.00009-8, ISBN 978-0-12-408087-4, retrieved 2020-04-14

- ↑ Christianson, Sven-Åke (1992). "Emotional stress and eyewitness memory: A critical review". Psychological Bulletin. 112 (2): 284–309. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.284. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 1454896.

- ↑ Rae Tuckey, Michelle (2003). "How schemas affect eyewitness memory over repeated retrieval attempts". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 17 (7): 785–800. doi:10.1002/acp.906.

- ↑ Pezdek, K.; Blandon-Gitlin, I.; Moore, C. (2003). "Children's Face Recognition Memory: More Evidence for the Cross-Race Effect" (PDF). Journal of Applied Psychology. 88 (4): 760–763. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.365.6517. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.760. PMID 12940414. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ↑ Elfenbein, H. A.; Ambady, N. (2003). "When familiarity breeds accuracy: Cultural exposure and facial emotion recognition". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 85 (2): 276–290. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.200.1256. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.276. PMID 12916570. S2CID 16511650.

- ↑ Loftus, E.F. (1975). "Leading Questions and the Eyewitness Report" (PDF). Cognitive Psychology. 7 (4): 560–572. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(75)90023-7. S2CID 16731808. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-06-19. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ↑ Cherry, K. (2010, June 7). Memory Retrieval - How Information is Retrieved From Memory. Psychology - Complete Guide to Psychology for Students, Educators & Enthusiasts.

- ↑ "Cue-dependent forgetting". APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. n.d. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ↑ Willingham, D.B. (2001). Cognition: The thinking animal. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ↑ "Priming". APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. n.d. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- ↑ Cherry, K. (2009, March 26). Priming - What Is Priming. Psychology - Complete Guide to Psychology for Students, Educators & Enthusiasts.

- ↑ Loftus, EF; Palmer JC (1974). "Reconstruction of Automobile Destruction : An Example of the Interaction Between Language and Memory" (PDF). Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 13 (5): 585–9. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(74)80011-3. S2CID 143526400.

- ↑ Brignull, H. (2010, March 16). The reconstructive nature of human memory (and what this means for research documentation). User Experience Design, Research and Usability.

- ↑ Robins, Sarah K. (2019-06-01). "Confabulation and constructive memory". Synthese. 196 (6): 2135–2151. doi:10.1007/s11229-017-1315-1. ISSN 1573-0964. S2CID 46967747.

- ↑ Moscovitch M. 1995. Confabulation. In (Eds. Schacter D.L., Coyle J.T., Fischbach G.D., Mesulum M.M. & Sullivan L.G.), Memory Distortion (pp. 226-251). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Nalbantian, Suzanne; Matthews, Paul M.; McClelland, James L., eds. (2010). The memory process : neuroscientific and humanistic perspectives. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01457-1.

- ↑ Waulhauser, G. (2011, July 11). Selective memory does exist. The Telegraph.