Pahang

Paha, Pahaeng, Pahaq | |

|---|---|

| Pahang Darul Makmur ڤهڠ دار المعمور | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Jawi | ڤهڠ |

| • Chinese | 彭亨 |

| • Tamil | பகாங் Pakāṅ {{{text}}} |

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem: Allah Selamatkan Sultan Kami الله سلامتکن سلطان کامي Allah, Save Our Sultan | |

| |

OpenStreetMap | |

| Coordinates: 3°45′N 102°30′E / 3.750°N 102.500°E | |

| Capital (and largest city) | Kuantan |

| Royal capital | Pekan |

| Government | |

| • Type | Parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| • Sultan | Abdullah II |

| • Regent | Tengku Hassanal |

| • Menteri Besar | Wan Rosdy Wan Ismail (BN-UMNO) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 35,965 km2 (13,886 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,187 m (7,175 ft) |

| Population (2018)[3] | |

| • Total | 1,675,000 |

| • Density | 47/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Pahangite, Pahangese, Pahanese (Football team fans slang) |

| Demographics (2010)[4] | |

| • Ethnic composition |

|

| • Dialects | Pahang Malay • Terengganu Malay • Semai • Semelai • Temiar • Jah Hut • Other ethnic minority languages |

| State Index | |

| • HDI (2019) | 0.804 (very high) (6th)[5] |

| • TFR (2017) | 2.2[2] |

| • GDP (2016) | RM50,875 million[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+8 (not observed) |

| Postal code | 25xxx to 28xxx, 39xxx, 49000, 69000 |

| Calling code | 09 (Pahang except as noted) 05 (Cameron Highlands) 03 (Genting Highlands) |

| ISO 3166 code | MY-06 |

| Vehicle registration | C |

| Modern Sultanate | 1881 |

| Federated into FMS | 1895 |

| Japanese occupation | 1942 |

| Accession into the Federation of Malaya | 1 February 1948 |

| Independence as part of the Federation of Malaya | 31 August 1957 |

| Federated as part of Malaysia | 16 September 1963 |

| Website | Official website |

Pahang (Malay pronunciation: [paˈhaŋ];Jawi: ڤهڠ, Pahang Hulu Malay: Paha, Pahang Hilir Malay: Pahaeng, Ulu Tembeling Malay: Pahaq), officially Pahang Darul Makmur with the Arabic honorific Darul Makmur (Jawi: دار المعمور, "The Abode of Tranquility") is a sultanate and a federal state of Malaysia. It is the third largest Malaysian state and the largest state in peninsular by area, and ninth largest by population.[2] The state occupies the basin of the Pahang River, and a stretch of the east coast as far south as Endau. Geographically located in the East Coast region of the Peninsular Malaysia, the state shares borders with the Malaysian states of Kelantan and Terengganu to the north, Perak, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan to the west, Johor to the south, while South China Sea is to the east. The Titiwangsa mountain range that forms a natural divider between the Peninsula's east and west coasts is spread along the north and south of the state, peaking at Mount Tahan, which is 2,187 metres (7,175 ft) high. Although two thirds of the state is covered by dense rain forest, its central plains are intersected by numerous rivers, and along the coast there is a 32-kilometre (20 mi) wide expanse of alluvial soil that includes the deltas and estuarine plains of the Kuantan, Pahang, Rompin, Endau, and Mersing rivers.[6]

The state is divided into 11 districts (daerah) - Pekan, Rompin, Maran, Temerloh, Jerantut, Bentong, Raub, Lipis, Cameron Highlands and Bera. The largest district is Jerantut, which is the main gateway to the Taman Negara national park. Pahang's capital and largest city, Kuantan, is the eighth largest urban agglomerations by population in Malaysia. The royal capital and the official seat of the Sultan of Pahang is located at Pekan. Pekan was also the old state capital which its name translates literally into 'the town', it was known historically as 'Inderapura'.[7] Other major towns include Temerloh, Bentong and its hills resorts of Genting Highlands and Bukit Tinggi. The head of state is the Sultan of Pahang, while the head of government is the Menteri Besar. The government system is closely modeled on the Westminster parliamentary system. The state religion of Pahang is Islam, but grants freedom to manifest other religions in its territory.

Archaeological evidences revealed the existence of human habitation in the area that is today Pahang from as early as the paleolithic age. The early settlements gradually developed into an ancient maritime trading state by the 3rd century.[8] In the 5th century, the Old Pahang sent envoys to the Liu Song court. During the time of Langkasuka, Srivijaya and Ligor, Pahang was one of the outlying dependencies. In the 15th century, the Pahang Sultanate became an autonomous kingdom within the Melaka Sultanate. Pahang entered into a dynastic union with Johor Empire in the early 17th century and later emerged as an autonomous kingdom in the late 18th century. Following the bloody Pahang Civil War that was concluded in 1863, the state under Tun Ahmad of the Bendahara dynasty, was eventually restored as a Sultanate in 1881. In 1895, Pahang became a British protectorate along with the states of Perak, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan. During the World War II, Pahang and other states of Malaya were occupied by the Empire of Japan from 1941 to 1945. After the war, Pahang became part of the temporary Malayan Union before being absorbed into the Federation of Malayas and gained full independence through the federation. On 16 September 1963, the federation was enlarged with the inclusion of new states of North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore (expelled in 1965). The federation was opposed by neighbouring Indonesia, which led to the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation over three years along with the continuous war against local Communist insurgents.

Modern Pahang is an economically important state with main activities in services, manufacturing and agricultural sectors. As part of ECER, it is a key region for the manufacturing sector, with the local logistics support network serving as a hub for the entire east coast region of Peninsular Malaysia.[9] Over the years, the state has attracted much investment, both local and foreign, in the mineral sector. Important mineral exports include iron ore, gold, tin and bauxite. Malaysia's substantial oil and natural gas fields lie offshore in the South China Sea. At one time, timber resources also brought much wealth to the state. Large-scale development projects have resulted in the clearing of hundreds of square miles of land for oil palm and rubber plantations and the resettling of several hundred thousand people in new villages under the federal agencies and institutions like FELDA, FELCRA and RISDA.

Etymology

The Khmer word for tin is pāhang[10] (ប៉ាហាំង) and it is phonetically identical to ڤهڠ (note that the Jawi spelling, literally, "phŋ", deviates[11] from modern DBP rule although its sound is unmistakably /paahaŋ/, note that the long ā sound is not explicitly rendered or stressed in old Jawi, just like ڤد). Since the tin mines at Sungai Lembing were known since ancient times and that the Malay peninsula was within the sphere of influence of Khmer civilization, William Linehan hypothesized[7] that the name of the state was named after the Khmer term of the mineral (note that tin-rich Perak is also etymologically linked to the same mineral).

We can then use this lexemic starting point to explain other derivatives such as Pahang the river, Mahang the place (name given to Pahang by Jakuns), Mahang the tree (Macaranga, a common tree species in secondary forests, likely named after the toponym of the same phoneme).[7] The Proto-Malays of Sungai Bebar who interacted with Trito-Malays likely acquired the term from their city counterparts and the name was fossilized their memory. The theory that the state was named after the a river or a tree is unsatisfactory as we still need to explain how the river or the tree got their names.

There were many variations of the name Pahang outside the Malay world. For examples, Song dynasty author Zhao Rukuo 趙汝适 wrote in Zhufanzhi 諸蕃志 (circa 1225) that Phong-hong (蓬豐 romanized according to Southern Min dialect since Zhao is from Quanzhou) was a dependency of Srivijaya. The transition from Inderapura to Pahang, approximately around the Song period indicates that Khmer influence on the state was weakened and displaced by that of Srivijaya and Majapahit.

In Yuan dynasty, Pahang is known as Phenn-Khenn 彭坑 in Daoyi Zhilue 島夷志略 (circa 1349), and in Ming Shilu 明實錄 (circa 1378), it was transliterated as Pen-Heng 湓亨, and in Haiguo Wenjianlu 海國聞見錄 (circa 1730), compiled in the Qing period, Pahang was transliterated as 邦項 (Pang-hang).

Arabs and Europeans, on the other hand, transliterated Pahang to Pam, Pan, Paam, Paon, Phaan, Phang, Paham, Pahan, Pahaun, Phaung, Phahangh.[7]

History

Old Pahang 5–15th century

Pahang Sultanate 1470–1623

Old Johor Sultanate 1623–1770

Pahang Kingdom 1770–1881

Federated Malay States 1895–1941

Empire of Japan 1942–1945

Malayan Union 1946–1948

Federation of Malaya 1948–1963

Malaysia 1963–present

Prehistory

Archaeological evidences revealed the existence of human habitation in the area that is today Pahang from as early as the paleolithic age. At Gunung Senyum have been found relics of Mesolithic civilisation using paleolithic implements. At Sungai Lembing, Kuantan, have been discovered paleolithic artefacts chipped and without trace of polishing, the remains of a 6,000 years old civilisation.[12] Traces of Hoabinhian culture is represented by a number of limestone cave sites.[13] Late neolithic relics are abundant, including polished tools, quoit discs, stone ear pendants, stone bracelets and cross-hatched bark pounders.[12] By around 400 BC, the development of bronze casting led to the flourishing of the Đông Sơn culture, notably for its elaborate bronze war drums.[14]

The early iron civilisation in Pahang that began around the beginning of Common Era is associated by prehistorians with the late neolithic culture. Relics from this era, found along the rivers are particularly numerous in Tembeling Valley, which served as the old main northern highway of communication. Ancient gold workings in Pahang are thought to date back to this early Iron Age as well.[13]

Hindu-Buddhist Era

The Kra Isthmus region of the Malay peninsula and its peripheries are recognised by historians as the cradle of Malayic civilisations.[15] Primordial Malayic kingdoms are described as tributaries to Funan by the 2nd century Chinese sources.[16] Ancient settlements in Pahang can be traced from Tembeling to as far south as Merchong. Their tracks can also be found in the deep hinterland of Jelai, along the Chini Lake, and up to the head-waters of the Rompin.[17] One such settlement was identified as Koli in Geographia or Kiu-Li, centred on the estuary of Pahang River south of Langkasuka, that flourished in the 3rd century CE. It possessed an important international port, where many foreign ships stopped to barter and resupply.[18] In common with most of the states in the Malay Peninsula during that time, Kiu-Li was in contact with Funan. The Chinese records mention that an embassy sent to Funan by the Indian King Murunda sailed from Kiu-Li's port (between 240 and 245 CE). Murunda presented to the Funanese King Fan Chang four horses from the Yuezhi (Kushan) stud farms.[8]

By the middle of the 5th century, a polity suggestive as ancient Pahang, was described in the Book of Song as Pohuang or Panhuang (婆皇). The king of Pohuang, She-li Po-luo-ba-mo ('Sri Bhadravarman'), was recorded to have sent an envoy to the Liu Song court in 449–450. In 456–457, another envoy of the same country arrived at the Chinese capital, Jiankang.[19] This ancient Pahang is believed to had been established later as a mueang[20] to the mandala of Langkasuka-Kedah centred in modern-day Patani region that rose to prominence with the regression of Funan from the 6th century.[21] By the beginning of the 8th century, Langkasuka-Kedah was in turn came under the military and political hegemony of Srivijaya.[22] In the 11th century, the power vacuum left by the collapse of Srivijaya was filled by the rise of Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom, commonly known in Malay tradition as 'Ligor'. During this period, Pahang, designated as Muaeng Pahang[20] was established as one of the twelve naksat city states[23] of Ligor.[24]

In the 14th century, Pahang began consolidating its influence in the southern part of the Malay peninsula. The kingdom, described by Portuguese historian, Manuel Godinho de Erédia as Pam, was one of the two kingdoms of Malayos in the peninsula, in succession to Pattani, that flourished before the establishment of Melaka. The Pahang ruler then, titled Maharaja, was also the overlord of countries of Ujong Tanah ('land's end'), the southerly part of the peninsula including Temasek.[25] The Majapahit chronicle, Nagarakretagama even used the name Pahang to designate the Malay peninsula, an indication of the importance of this kingdom.[26] The History of Ming records several envoy missions from Pahang to the Ming court in the 14th and 15th centuries. In the year 1378, Maharaja Tajau sent envoys with a letter on a gold leaf and bringing as tribute six foreign slaves and products of the country. In the year 1411, during the reign of Maharaja Pa-la-mi-so-la-ta-lo-si-ni (transliterated by historian as 'Parameswara Teluk Chini'), he also sent envoys carrying tributes.[27]

Old sultanate

The Old Pahang Sultanate centred in modern-day Pekan was established in the 15th century. At the height of its influence, the Sultanate was an important power in Southeast Asian history and controlled the entire Pahang basin, bordering to the north, the Pattani Sultanate, and adjoins to that of Johor Sultanate to the south. To the west, it also extends jurisdiction over part of modern-day Selangor and Negeri Sembilan.[28]

The sultanate has its origin as a vassal to Melaka, with its first Sultan was a Melakan prince, Muhammad Shah, himself the grandson of Dewa Sura, the last pre-Melakan ruler of Pahang.[28] Over the years, Pahang grew independent from Melakan control and at one point even established itself as a rival state to Melaka[29] until the latter's demise in 1511. In 1528, the last Sultan of Melaka, Mahmud Shah died. Pahang joined forces with his successor, Alauddin Riayat Shah II who established himself in Johor to expel the Portuguese from the Malay Peninsula. Two attempts were made in 1547 at Muar and in 1551 at Portuguese Malacca. However, in the face of superior Portuguese arms and vessels, the Pahang and Johor forces were forced to retreat on both occasions.[30]

During the reign of Sultan Abdul Kadir, Pahang enjoyed a brief period of cordial relations with the Portuguese. However, this relationship was discontinued by his successor, Sultan Ahmad II. The next ruler, Sultan Abdul Ghafur attacked the Portuguese and simultaneously challenged the Dutch presence in the Strait of Malacca. Nevertheless, in 1607, Pahang not only tolerated the Dutch, but, following a visit by Admiral Matelief de Jonge, even cooperated with them in an attempt to get rid of the Portuguese.[30]

The Sultan tried to reforge the Johor-Pahang alliance to assist the Dutch. However, a quarrel which erupted between Sultan Abdul Ghafur and Alauddin Riayat Shah III of Johor, resulted in Johor declaring war on Pahang in 1612. With the aid of Sultan Abdul Jalilul Akbar of Brunei, Pahang eventually defeated Johor in 1613. Sultan Abdul Ghafur's son, Alauddin Riyat Shah succeeded the throne in 1614. In 1615, the Acehnese under Iskandar Muda invaded Pahang, forcing Alauddin Riayat Shah to retreat into the interiors. He nevertheless continued to exercise some ruling powers. His reign in exile is considered officially ended after the installation of a distant relative, Raja Bujang to the Pahang throne in 1615, with the support of the Portuguese following a pact between the Portuguese and Sultan of Johor.[30]

Raja Bujang who reigned as Abdul Jalil Shah was eventually deposed in the Acehnese invasion in 1617, but restored to the Pahang throne and also installed as the new Sultan of Johor following the death of his uncle, Abdullah Ma'ayat Shah in 1623. This event led to the union of the crown of Pahang and Johor, and the formal establishment of Johor Empire.[30]

Modern history

.jpg.webp)

The modern Pahang kingdom came into existence with the consolidation of power by the Bendahara family in Pahang, following the gradual dismemberment of Johor Empire. A self-rule was established in Pahang in the late 18th century, with Tun Abdul Majid declared as the first Raja Bendahara.[31] The area around Pahang formed a part of the hereditary domains attached to this title and administered directly by the Raja Bendahara. The weakening of the Johor sultanate and the disputed succession to the throne was matched by an increasing independence of the great territorial magnates; the Bendahara in Pahang, the Temenggong in Johor and Singapore, and the Yamtuan Muda in Riau.[32]

In 1853, the fourth Raja Bendahara Tun Ali, renounced his allegiance to the Sultan of Johor and became independent ruler of Pahang.[33][34] He was able to maintain peace and stability during his reign, but his death in 1857 precipitated civil war between his sons. The younger son Wan Ahmad challenged the succession of his half-brother Tun Mutahir, in a dispute that escalated into a civil war. Supported by the neighbouring Terengganu Sultanate and the Siamese, Wan Ahmad emerged victorious, establishing controls over important towns and expelled his brother in 1863. He served as the last Raja Bendahara, and was proclaimed Sultan of Pahang by his chiefs in 1881.[34]

Due to internal strife within Pahang, the British pressured Sultan Ahmad to acquiesce to the presence of a British adviser. Aided by Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor and William Fraser of the Pahang Mining Company, they succeeded in convincing Sultan Ahmad to accept a British agent, Hugh Clifford, in December 1887. In October 1888, Sultan Ahmad reluctantly accepted John Pickersgill Rodger as Pahang's first Resident. Following the intervention, Sultan Ahmad became a Ruler-in-Council and acted in accordance with the advice of the British Resident and the State Council, except in matters pertaining Islam and Malay customs. Taxes were to be collected in the name of the Sultan by the Resident, with the assistance of European officers.[35]

Between 1890 and 1895, Dato' Bahaman, the Orang Kaya Setia Perkasa Pahlawan of Semantan, and Imam Perang Rasu, the Orang Kaya Imam Perang Indera Gajah of Pulau Tawar, led a revolt against the British encroachment. Sultan Ahmad appeared to be co-operating with the British, but his sympathies were known to be for the dissidents. By 1895 the revolt was suppressed by the British and many of the dissidents surrendered. In July 1895, Sultan Ahmad signed the Federation Agreement, which made Pahang, along with Perak, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan, one of the Federated Malay States, the protectorate state of the British Empire. This had effectively reduced the Sultan's powers and authority, as did the creation of Federal Council in 1909. The executive and legislative functions of the State Council became increasingly nominal.[35]

Like other Malay States, Pahang suffered during the Japanese occupation of Malaya until the year 1945. During the Japanese Occupation, the reigning Sultan Abu Bakar opened a large potato plantation behind the Terentang Palace to help ease the food shortage and he personally approved proposals to form the Askar Wataniah, an underground Malay resistance force. The Sultan spent the final days of the Occupation in a jungle hideout with members of Force 136, resistance fighters and refugees. In late 1945, to mark the decommissioning of the Askar Wataniah, the troops paraded through Pekan and submitted to a royal inspection, after which they were feted at the Sa'adah Palace with what has been called 'the first ronggeng of the liberation'.[36]

During his reign, Sultan Abu Bakar revived the office of State Mufti and established the Pahang Islamic and Malay Customs Council. The state's administrative capital, which was established in Kuala Lipis during British intervention, was moved to Kuantan.[36]

After World War II, Pahang formed the Federation of Malaya with other eight Malay States and two British Crown Colonies Malacca and Penang in 1948. The semi-independent Malaya gained was granted independence in 1957, and was then reconstituted as Malaysia with the inclusion the states of Singapore (left the federation in 1965), Sabah and Sarawak in 1963.

Geography

Pahang covers an area of 35,965 km2 (13,886 sq mi),[2] and is the third largest state in Malaysia after Sabah and Sarawak, and the largest in the Peninsular Malaysia. Geographically diverse, Pahang occupies the vast Pahang River basin, which is enclosed by the Titiwangsa Range to the west and the eastern highlands to the north. Although about 2/3 of the state is dense jungle,[37] its central plains are intersected by numerous rivers, joining to form the Pahang River which dominates the drainage system. Pahang is divided into three ecoregions, the freshwater systems, the lowlands and highlands rainforests and the coastline.[6]

The Pahang River basin connects with Malaysia's two largest natural freshwater lakes, Bera and Chini. Described as wetland of international importance, Bera Lake was accepted as Malaysia's first Ramsar site in 1994.[38]

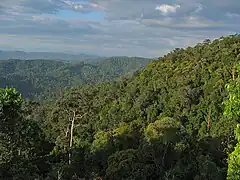

The highest peak, Mount Tahan, reaches 2,187 m (7,175 ft) in elevation, which is also the highest point in the Peninsular Malaysia. The climate is temperate enough to have distinct temperature variations year round, and much of the highlands are covered with tropical rainforest. Pahang is home to Malaysia's two important national parks, Taman Negara and Endau-Rompin, both located in the north and south of the state respectively. These large primary rainforests are extensive, and are home to many rare or endangered animals, such as the tapir, kancil, tigers, elephants and leopards. Ferns are also extremely common, mainly due to the high humidity and fog that permeates the area. Popular hill resorts located along these main highland areas are Cameron Highlands, Genting Highlands, Fraser's Hill and Bukit Tinggi. The Cameron Highlands is home to extensive tea plantations and also a major supplier of legumes and vegetables to both Malaysia and Singapore. The largest FELDA's palm oil plantations in Malaysia are located in Jengka Triangle centred around the Bandar Tun Razak in Maran district.

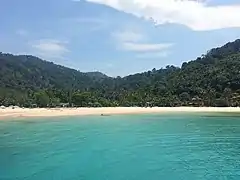

Pahang's long, scenic coastline is a paradise of swaying palms and sandy beaches like Cherating, Teluk Cempedak, Beserah, Batu Hitam and Tanjung Sepat. Also located along the coastal plain, is a 32 km2 (12 sq mi) wide expanse of alluvial soil that includes the deltas and estuarine plains of the Kuantan, Pahang, Rompin, Endau, and Mersing rivers.[6] Important economic centres can be found along the coastline, where both capital and royal capital of the state, Kuantan and Pekan, are located. About 58 km off the coast of Pahang lies Tioman Island, an alluring holiday paradise in the South China Sea, acclaimed as one of the best island getaways in the world.[39]

Pahang has a tropical geography with an equatorial climate and a year-round of humidity of no less than 75%. It is warm and humid throughout the year with temperatures ranging from 21 °C to 33 °C. The rainfall here averages 200 mm monthly, a large proportion of which occurs during the northeast monsoon. Precipitation is the lowest in March, with an average of 22.25 mm. In October and November, the precipitation reaches its peak, with an average of 393 mm. The hottest month in Pahang is May when the average maximum temperature is 33°, average temperature is 28° and average minimum temperature is 24°. At highland areas, the temperature can vary from 23 °C (73 °F) during daytime to 16 °C (61 °F) during night time.[40][41]

Pahang experiences two monsoon seasons: a northeast monsoon and a southwest monsoon. The tropical storms of the northeast monsoon wash ashore from the end of October till the beginning of March ever year, bringing heavy rainfall, powerful currents and unpredictable tempest of the monsoon season coming in from the South China Sea. The southwest monsoon, which occurs beginning March every year, brings somewhat less rainfall, with sunny and tropical weather up until the end of October.[40]

- Landscapes of Pahang

Mount Tahan, the highest mountain of Peninsular Malaysia.

Mount Tahan, the highest mountain of Peninsular Malaysia.

View of Taman Negara.

View of Taman Negara..jpg.webp) South China Sea view from Tioman Island.

South China Sea view from Tioman Island.

Biodiversity

Malaysia, as a nation, is considered one of the most biodiverse on earth.[42] Pahang maintains a protected network of managed areas rich in flora, fauna, and natural resources, in spite of deforestation, rapid industrialisation and an ever-growing population. In Pahang, there are some 74 forest reserves, including ten virgin-jungle reserves and 13 different amenity forests, wildlife reserves, national parks and offshore marine parks. Of these, the Pahang segment of Taman Negara is the most outstanding. There are many other examples of nationally- and internationally-relevant areas, including the Krau Wildlife Reserve, Bera Lake Ramsar Site, Tioman Island Marine Park and Cameron Highlands Wildlife Sanctuary.[43]

Total forest in Pahang is about 2,367,000 ha (66% of the land area), of which 89% is a dryland forest, 10% peat swamp forest, and 1% mangroves. About 56% of the total forest is within the Permanent Forest Estate. This includes almost the full range of forest types found in Malaysia, although some of the more unique environments (such as heath forest or forest on ultrabasic rocks) exist only in fragmented areas of Pahang. The protected forest within Taman Negara and Krau Wildlife Reserve includes small areas of extreme lowland alluvial plains. Elsewhere, most of the dryland forest in Pahang is on steep slopes, therefore benefiting from both catchment protection and slope protection functions.[43] Virtually every species of bird and mammal known from Peninsular Malaysia has been recorded in Pahang, other than a few confined to the north of the country or the west coast. The representation of montane species of plants and animals is particularly numerous. Peaks within Taman Negara, Mount Benom, and peaks along the Titiwangsa Range, with different endemic species in each of these montane regions are located in Pahang. The large forest blocks of the west and northeast support nationally important populations of big mammals and other fauna, and act as a unit with Taman Negara.[44]

Pahang River is the longest river in the Peninsula, and from its headwaters to the estuary it includes virtually all of the natural river types. These range from montane streams, saraca streams and neram rivers to rasau and nipah tidal reaches. Water catchments have been defined as covering 81% of the state and more than half of this is forested.[45] The huge network of rivers in Pahang is home to freshwater aquatic biodiversity, important to the economy of the state. Connecting to this riverine systems are a number of natural freshwater lakes, most notably Bera and Chini lakes. Surrounded by a patchwork of dry lowland dipterocarp forests, the lake environment stretches its tentacles into islands of peat swamp forests. Rich in wildlife and vegetation, the lakes provide an ecosystem which supports not only a diversity of animal and plant life, but sustains the livelihood of the Orang Asal, the aboriginal people inhabiting the wetlands.

Most of the coastline is sandy, with rocky headlands at intervals. Mangroves and nipah swamps are confined to estuaries and do not occur along the exposed coast. These estuaries can be seasonally important to fishermen when rough weather prevents fishing at sea. There are limited areas of hard and soft coral offshore, which have been mapped together with coastal features. There are many islands off the east coast, the largest being Tioman and Seri Buat islands. Besides the island populations of fauna and flora, which sometimes differ genetically from mainland forms of the same species, these islands are of value for the reefs and other bottom features which support marine biological diversity. The reefs in particular are sensitive to sedimentation from activities on land. These features are related to the maintenance of marine fisheries, an important sector of the coastal economy. Tioman, Chebeh, Tulai, Sembilang and Seri Buat islands constitute the Tioman group of islands within the Marine Parks system of Peninsular Malaysia.[46]

Politics and government

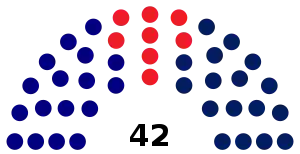

| |||||

| Affiliation | Coalition/Party Leader | Status | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 election | Current | ||||

| |

Barisan Nasional Pakatan Harapan |

Wan Rosdy Wan Ismail | Government | 25 | 25 |

| Perikatan Nasional | Tuan Ibrahim Tuan Man | Opposition | 17 | 17 | |

| Total | 42 | 42 | |||

| Government majority | 8 | 24 | |||

The modern constitution of Pahang, the Undang-Undang Tubuh Kerajaan Pahang, was first drafted on 1 February 1948. It was formally adopted on 25 February 1959. The constitution proclaims that Pahang is a constitutional monarchy. The constitutional head is the Sultan, who is described as "the fountain head of justice and of all authority of government" in the state. He who is vested with the power as a monarch of the state, is also the Head of Islam and the source of all titles and dignities, honours and awards.[47][48] The current Sultan belong to the male line of the Bendahara dynasty who have been ruling the state since the 17th century.[31] Since 2019, the reigning monarch has been Abdullah. He was proclaimed as Sultan on 15 January 2019, succeeding his father, Ahmad Shah, whose abdication was decided at a Royal Council meeting on 11 January. On 24 January 2019, days after his accession to the throne of Pahang, he was elected as the 16th Yang di-Pertuan Agong of Malaysia, succeeding Muhammad V who abdicated from the throne on 6 January. Succession order to the throne of Pahang is generally determined roughly by agnatic primogeniture. No female may become ruler, and female line descendants are generally excluded from succession. In Pahang traditional political structure, the offices of Orang Besar Berempat ('four major chiefs') are the most important positions after the Sultan himself. The four hereditary territorial magnates are; Orang Kaya Indera Pahlawan, Orang Kaya Indera Perba Jelai, Orang Kaya Indera Segara and Orang Kaya Indera Shahbandar. Next in the hierarchy were the Orang Besar Berlapan ('eight chiefs') and Orang Besar Enam Belas ('sixteen chiefs') who were subordinated to the principal nobles.[32]

The Sultan headed two institutions, the State Legislative Assembly and State Executive Council.[49] The legislative branch of the state is the unicameral Dewan Undangan Negeri ('State Legislative Assembly') whose 42 members are elected from single-member constituencies. The assembly has the power to enact the state laws. State government is led by a Menteri Besar, who is a member of the State Legislative Assembly from the majority party. According to the constitution of Pahang, the Menteri Besar is required to be a Malay and a Muslim, appointed by the ruler from the party that commands the majority of the State Legislative Assembly.[48] By convention, state elections are held concurrently with the federal election, held at least once every five years, the most recent of which took place in May 2018. Registered voters of age 21 and above may vote for the members for the state legislative chamber.[50]

Executive power is vested in the State Executive Council as per 1959 constitution. It consists of the Mentri Besar, who is its chairman, and 13 other members.[51] The Sultan of Pahang appoints the Mentri Besar and the rest of the council from the members of the State Assembly. The Mentri Besar is both the head of the Executive Council and the head of the State Government.[48] The incumbent, Dato' Seri Wan Rosdy Wan Ismail from the United Malays National Organisation, a major component party of the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition, appointed in 2018, is the 15th Mentri Besar.[52]

As a federal state, Pahang is subjected to Malaysia's legal system which is based on English Common Law. The highest court in the judicial system is the Federal Court, followed by the Court of Appeal and the High Court of Malaya. Malaysia also has a special court to hear cases brought by or against royalty. The death penalty is in use for serious crimes such as murder, terrorism, drug trafficking, and kidnapping. Separate from and running parallel to the civil courts, are the Syariah Court, which apply Sharia law to Muslims in the areas of family law and religious observances. As provided in Article 3 of the Federal Constitution, Syariah or Islamic law is a matter of state law, passed in the State Legislative Assembly. Matters related to the enforcement of the Syariah law falls under the jurisdiction of the Jabatan Agama Islam Pahang ('Pahang Islamic Religious Department'). Pahang's constitution empowers the Sultan as the head of Islam and Malay customs in the state. State council known as Majlis Ugama Islam dan Adat Resam Melayu Pahang ('Council of Islam and Malay Customs of Pahang') is responsible in advising the ruler as well as regulating both Islamic affairs and adat.[48]

Subdivisions

Pahang is divided into 11 administrative districts, which in turn is divided into 66 mukims.[53] Currently, there are also 4 subdistricts in Pahang, which is Genting, Gebeng, Jelai and Muadzam Shah.[54] For each district, the state government appoints a district officer who heads lands and district office. An administrative district can be distinguished from a local government area where the former deals with land administration and revenue[55] while the latter deals with the planning and delivery of basic infrastructure to its inhabitants. Administrative district boundaries are usually coextensive with local government area boundaries but may sometimes differ especially in urbanised areas. Local governments in Pahang consist of 3 municipal councils and 8 district councils.[56]

The administrative divisions in Pahang are originated from the time of the old Pahang Sultanate, whereby territorial magnates appointed by the Sultan to administer the historical divisions of the state.[57] The largest historical divisions were; Jelai (corresponds to modern day Lipis District), Temerloh, Chenor (corresponds to modern day Maran District) and Pekan, each administered by the four major chiefs (Orang Besar Berempat). Next in the hierarchy were the Orang Besar Berlapan ('eight chiefs') and then Orang Besar Enam Belas ('sixteen chiefs') who were subordinated to their respective principal nobles. The lowest of this traditional hierarchy are the Tok Empat or village headmen who were subordinated to Tok Mukim, who in turn subordinated to Tok Penghulu, who in turn subordinated to one of the sixteen chiefs.[32]

In modern times, the Tok Empat became formally known as Ketua Kampung (literally 'village headman'), although continued to be referred as such informally. He is subordinated to a Penghulu, the head of the mukim, who in turn subordinated to the district officer.

| Administrative divisions of Pahang | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Districts | Seat | Local government level[56] | Mukim[53] | Area (km2) | Population (2010)[58] |

| 1 | Bera | Bandar Bera | District Council | Bera, Teriang | 2,214 | 93,084 |

| 2 | Bentong | Bentong | Municipality | Bentong, Sabai, Pelangai Autonomous sub-districts: Genting Highlands[59][60] | 1,381 | 112,678 |

| 3 | Cameron Highlands | Tanah Rata | District Council | Hulu Telom, Ringlet, Tanah Rata | 712 | 37,147 |

| 4 | Jerantut | Jerantut | District Council | Bulau, Hulu Cheka, Hulu Tembeling, Kelola, Kuala Tembeling, Pedah, Pulau Tawar, Tebing Tinggi, Teh, Tembeling | 7,561 | 87,709 |

| 5 | Kuantan | Kuantan | City | Kuala Kuantan, Hulu Kuantan, Sungai Karang, Beserah, Hulu Lepar, Penor Autonomous sub-districts: Gebeng[61] | 2,960 | 450,211 |

| 6 | Lipis | Kuala Lipis | District Council | Batu Yon, Budu, Cheka, Gua, Hulu Jelai, Kechau, Kuala Lipis, Penjom, Tanjung Besar, Telang Autonomous sub-districts: Jelai[62] | 5,198 | 86,200 |

| 7 | Maran | Maran | District Council | Bukit Segumpal, Chenor, Kertau, Luit | 3,805 | 113,303 |

| 8 | Pekan | Pekan | Municipality | Bebar, Ganchong, Kuala Pahang, Langgar, Lepar, Pahang Tua, Pekan, Penyor, Pulau Manis, Pulau Rusa, Temai | 3,846 | 105,822 |

| 9 | Raub | Raub | District Council | Batu Talam, Dong, Gali, Hulu Dong, Sega, Semantan Hulu, Teras | 2,269 | 91,169 |

| 10 | Rompin | Kuala Rompin | District Council | Endau, Keratong, Pontian, Rompin, Tioman, Bebar Autonomous sub-districts: Bandar Muadzam Shah[63] | 5,296 | 110,286 |

| 11 | Temerloh | Temerloh | Municipality | Bangau, Jenderak, Kerdau, Lebak, Lipat Kajang, Mentakab, Perak, Sanggang, Semantan, Songsang | 2,251 | 155,756 |

Economy

Pahang GDP share by sector (2016)[64]

As a federal state of Malaysia, Pahang is a relatively open state-oriented market economy.[65] The Pahang State Government Development Corporation, established in 1965, carries the responsibility to drive the economic and social development, by attracting investments, promoting industrial, property and entrepreneurial development, and setting up new commercial hubs and townships.[66] The federal government, through a series development initiatives and programs, the most recent is the East Coast Economic Region introduced in 2007, is also credited for the robust economic growth in recent years. With GDP growing an average 5.6 per cent annually from 1971 to 2000, Pahang is considered a developing state.[67] In 2015, the state economy grew by 4.5%, the tenth highest among 15 states and federal territories of Malaysia, but later reduced to 2% in 2016.[68] The GDP per capita is recorded at $7,629.39 in 2016, while the unemployment rate was maintained below 3% from 2010 to 2016.[68] The economy of Pahang in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) at purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2016 was $12.414 billion, the eight largest in Malaysia. The amount constitutes 4.5% contribution to the national GDP, and largely driven by three main economic activities; Services (49%), Agriculture (23%), and Manufacturing (22.1%).[64]

Historically, by the 19th century, Pahang's economy, like in ancient times, was still heavily dependent on the export of gold. Gold mines can be found from Bera to Jelai River river basin.[69] Systematic mining started in 1889 during British protectorate, when the Raub Australian Gold mine was established. Extensive underground mining took place in the area and this continued until 1985 during which time the mine at Raub produced nearly 1 million ounces, 85% of the production of Peninsular Malaysia.[70] Another important article of export was tin, which was also mined in a large scale. The tin ore production was primarily concentrated at Sungai Lembing, where during its heyday, the operations saw the excavation of deep shaft mines that were among the largest, longest and deepest in the world.[71] The growth of the mining industry had a significant impact on Pahang's society and economy towards the end of the 19th century. Thousands of people were at work in the mines which places had, in consequence, become an important trading centres in the state.[72] Once an important industry, the mining industry along with quarrying, now accounts only 1.6% of the total state GDP in 2016.[64] Modern mining industry also include other minerals, in particular iron ore and bauxite. Pahang accounts for more than 70% of the Malaysia's estimated 109.1 million tonnes of bauxite reserves. Mining of the ore, used to make aluminium, surged in 2015 after neighbouring Indonesia prohibited the raw material from being sold overseas. China, instead, bought almost 21 million tonnes from Malaysia, valued at US$955.3 million.[73] Pahang iron ore production is concentrated at small-scale mines scattered across the state. The low grade iron ores were consumed by the pipe-coating industry that supplied the oil and gas sector and cement plants, while the high grades were exported.[74]

The services sector, which constitutes 49% of the total Pahang GDP, is predominantly stimulated by the Wholesale and Retail Trade, Food and Beverage and Accommodation, which amounts to $1.8 billion in 2016.[68] This sub sector, on the other hand, is the main driving factor for the growth of the tourism industry. With its richness in biodiversity, Pahang is offering ecotourism to its hill resorts, beaches and national parks. In 2014, the state attracted 9.4 million visitors, and the figure grew to 12 million in 2016. The agricultural sector is another key economic sector of the state.[75] Historically an agrarian economy, Pahang's agriculture was dominated by the production of vegetables, rice, yams and tubers in the past. With extensive support by the federal agencies and institutions like FELDA, FELCRA and RISDA, the agricultural sector was rapidly expanding, with the inclusion of products like rubber and palm oil as the main agricultural produce,[76][77] The state is home to the largest FELDA settlement known as 'Jengka Triangle' centred in Bandar Tun Razak, Maran District. Pahang was historically a primary exporter of forestry products like sandalwood, damar and rattans.[72] In modern times, the forestry remains the main sub-sector with tropical timber is an important produce, as large swaths of forest supported massive production of wood products.[78] Yet a decline in mature trees due to intensive harvesting lately has caused a slowdown and the practice of more sustainable forestry.[79] Fishery and aquaculture products are also a main source of income especially for the communities on the long coastline and large network of rivers of the state. Today, agriculture is the second largest component of the state economy which constitutes 23% of the total state GDP. It contributes approximately 12.3% of the federal GDP, the fourth largest after Sarawak, Sabah and Johor.[64] Under East Coast Economic Region (ECER) masterplan, introduced in 2007, the agro-businesses in the state is set to move up further the value chain, with the introduction of agricultural initiatives like Nucleus Cattle Breeding and Research Centre at Muadzam Shah, Rompin Integrated Pineapple Plantation, Kuantan-Maran Agrovalley for leafy vegetables and maize, as well as Pekan-Rompin-Mersing Agrovalley for watermelon, vegetables, roselle, and maize.[78]

The third largest component of Pahang economy is the manufacturing sector. It forms 22.1% of the state economy[64] and its growth is mainly driven by the many resource-based industries, including the processing of rubber, wood, palm oil, petrochemicals and other halal products. Pahang automotive industry, which is rapidly developing, is centred in Peramu Jaya Industrial Park in Pekan.[78] Home to well known automotive players including DefTech, Isuzu HICOM Malaysia, Mercedes-Benz and Suzuki, the industrial park is expected to expand into the 217ha Pekan Automotive Park, scheduled to complete in 2020. The expansion plan is expected to transform the area into a national and regional hub for car assembly, manufacturing of automotive parts and components, as well as automotive research and development activities.[80] This would be part of the manufacturing initiatives under East Coast Economic Region (ECER) masterplan, that would also involve development of other manufacturing industrial parks including Gebeng Integrated Petrochemical Complex (GIPC), Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park (MCKIP), Pahang Technology Park (PTP), Kuantan Integrated Bio Park (KIBP), and Gambang Halal Park (GHP). Most of these industrial parks are located within the ECER Special Economic Zone that stretches from district of Kerteh, Terengganu in the north to the district of Pekan, Pahang in the south. Envisioned to be the key engine of economic growth in the ECER, the economic zone is expected to attract $23 billion of Foreign Direct Investment and create 120,000 new jobs by 2020.[81]

Infrastructure

Infrastructure in Pahang, like the rest of the east coast region of Peninsular Malaysia, is still relatively underdeveloped compared to the west coast.[82] To reduce the development gap, the federal government, have been investing heavily in high impact development as well as in upgrading the existing infrastructures. Development grant to the state government amounts to $24.82 million in 2017.[83] In federal budget 2017, about $958 million allocation was announced for Malaysian states to improve the public infrastructures.[84] About 46% of the state annual budget are also allocated for the improvement of the state infrastructure. Pahang also financed much of its infrastructure projects under the privatisation concept, through 13 state statutory bodies including Pahang Development Corporation, Pahang State Foundation, Development Authority of Pahang Tenggara, Tioman Development Authority and Fraser's Hill Development Corporation.[85] Under the Tenth Malaysia Plan (2011-2015), $493 million has been allocated for 351 infrastructure projects in the state.[86] While under the Eleventh Malaysia Plan (2016-2020), $547 million has been allocated to Pahang, with infrastructure in the rural areas was given attention with the increase of rural water, electricity supply and road coverage.[87]

Peninsular Malaysia as a whole including Pahang, has almost 100% electrification.[88] Transmission and distribution of electricity in the state of Pahang lie under the responsibility of the national utility company, Tenaga Nasional.[89] The main power plant in Pahang is located in Cameron Highlands with installed capacity 250 MW that generates about 643 GWh of hydroelectricity.[90] Transmission voltages are at 500 kV, 275 kV and 132 kV while distribution voltages are 33 kV, 22 kV, 11 kV and 415 V three-phase or 240 V single-phase. System frequency is 50 Hz 1%. Under its Total Energy Solution, Tenaga Nasional also offers electricity packaged with steam and chilled water for the benefit of certain industries that require multiple forms of energy for their activities.[91]

Access to improved water source in Malaysia is 100%. The water supply in Pahang is managed by the Pahang Water Management Berhad or Pengurusan Air Pahang Berhad (PAIP). The department is also responsible for the planning, development, management of water supply as well as billing and collection of payment. In Pahang, water supply comes mainly from rivers and streams and there are about 79 water treatment plants located in various districts.[92] Pahang abundant water sources are also significant to the growing demand of water supply in Greater Kuala Lumpur and Selangor, the industrial heartland of Malaysia. The federal government initiated Pahang-Selangor Raw Water Transfer Project that includes the construction of the Kelau dam on the Pahang river, as well as the transfer of water via a tunnel through the Titiwangsa Mountains.[93]

Internet and telecommunication

In 2016, the household internet broadband penetration per 100 inhabitants in Pahang was relatively high among states of the east coast, but was lower than Malaysian national figure, 71.7 versus 99.8.[94] Extensive efforts to increase internet access, have been undertaken by the government since 2007 to bridge the digital divide, focusing especially the rural areas. Since 2013, the programs have been expanded to include underserved urban communities as well. As of 2015, 89 internet centres have been established in Pahang, in addition to 11 Mini Community Broadband centres and 1 Community Broadband Library. Community WiFi (WK) initiative has also been implemented by the government since 2011 to provide free internet access through Wifi hotspots. In Pahang alone, a total number of 199 Community Wi-Fi have been set up. In terms of fixed line broadband, suburban broadband initiatives were outlined in the Eleventh Malaysia Plan to increase broadband accessibility in suburban and rural areas. By 2016, the number of ports in Pahang was growing up to 7,936 ports, the fourth highest in Malaysia after Selangor, Johor and Perak.[95]

The mobile telecommunication penetration, although increasingly popular, was lower compared to the national figure per 100 inhabitants, 130.9 against national figure 143.8. Cellular coverage expansion in Pahang is served by 207 communication towers, with 3G mobile broadband coverage has been expanded to 150 sites and LTE mobile broadband to 42 sites respectively. To accommodate the demand for high-speed mobile broadband, the core network capacity has been upgraded, with fibre-optic network has been expanded in 2015 to a total 45.6 km.[96] In 2015, an initiative was announced by the federal government to connect the Peninsular and the East Malaysia states, Sabah and Sarawak with submarine fibre optic cable network bringing 4 terabits per second capacity with a total distance of approximately 3,800 kilometres. The planned submarine cable will connect the state of Pahang and Sabah through connecting points in Cherating and Kota Kinabalu respectively.[97]

Transportation

Much like many former British protectorates, Pahang uses a dual carriageway with the left-hand traffic rule. As of 2013, Pahang had a total of 19,132 kilometres (11,888 mi) of connected roadways, with 12,425 kilometres (7,721 mi) being paved state routes, 702 kilometres (436 mi) of dirt tracks, 2,173 kilometres (1,350 mi) of gravel roads, and 3,832.6 kilometres (2,381.5 mi) of paved federal road.[98] The primary route in Pahang is the East Coast Expressway, which is the extension of Kuala Lumpur–Karak Expressway, that connects the east coast and the west coast of the Peninsular Malaysia. The expressway passes through 3 states of the peninsular; Pahang, Terengganu and Selangor, connects Kuantan Port to the national grid and links many important town and cities of the east coast to the industrial heartland of Malaysia in the west. Another important route, the Central Spine Road which was laid out in the Eleventh Malaysian Plan, is an alternative road to the east coast, connecting Kuala Krai in Kelantan and Bentong District in Pahang.

The main railway line is the KTM East Coast Railway Line, nicknamed the 'Jungle Railway' for its route that passes through the sparsely populated and heavily forested interior. It is operated by Keretapi Tanah Melayu Berhad, a federal government-linked company. The 526 km long single track metre gauge that runs between Gemas in Negeri Sembilan and Tumpat in Kelantan, was historically used during British protectorate to transport Tin. A more advanced railway line, the double-track and electrified MRL East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), was announced in 2016 as a project under ECER's master plan, to transport both passengers and cargo. The planned 688 km long new railway line is set to form the backbone of ECER's multimodal transport infrastructure, linking the existing transportation hub in ECER Special Economic Zone (SEZ) with the west coast region.[99]

The Special Economic Zone that centred at Kuantan,[81] is the main transportation hub for bus services, air routes and sea routes for the entire east coast region. Terminal Kuantan Sentral serves as the land transportation hub, offering intrastate services that connects all districts of Pahang, as well as interstate services that links the state to the rest of the Peninsular, including Singapore and Thailand. In 2012, the government announced that Prasarana, which runs Rapid KL, would take over all public bus services in Kuantan under a new entity, Rapid Kuantan. The only airport in Pahang is Sultan Ahmad Shah Airport, also known as Kuantan Airport. Located 15 km from Kuantan, it serves both domestic and international flights. Direct international flights connect the state with Singapore. The airport serves the national carrier Malaysia Airlines and its low-cost subsidiary Firefly. It also houses the 6th Squadron and 19th Squadron of the Royal Malaysian Air Force.[100] Kuantan is also home to Pahang's only seaport, the Kuantan Port. The multipurpose seaport, that handles both intermodal containers and bulk cargo, is an important gateway of the international sea trading routes for the entire east coast region of Peninsular Malaysia. Since 2013, the port embarked on massive expansion program with the development of New Deep Water Terminal consisting 2 km berth extension, to be fully integrated with the Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park (MCKIP) and other neighbouring industrial parks within the Special Economic Zone. This expansion plan, along with other high impact development projects are in tandem with the escalating economic development of the Eastern Industrial Corridor.[81]

Healthcare

Pahang population has benefited from a well- developed Malaysian health care system, good access to clean water and sanitation, and strong social and economic programmes. Health care services consist of tax-funded and federal government-run primary health care centres and hospitals, and fast-growing private services mainly located in physician clinics and hospitals in urban areas. Infant mortality rate per 1000 live births, a standard in determining the overall efficiency of healthcare, in 2010 was 7.6.[101] As of national figure, infant mortality fell from 75 per 1000 live births in 1957 to 7 in 2013.[102] Life expectancy at birth in 2016 was 70.8 years for male and 76.3 years for female.[2]

The public healthcare system in Pahang is provided by five specialist government hospitals;[103] Tengku Ampuan Afzan Hospital, Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Hospital, Bentong Hospital, Kuala Lipis Hospital and Pekan Hospital, as well as other district hospitals, public health clinics, 1Malaysia clinics, and rural clinics. There are several private hospitals in Pahang, including Kuantan Medical Centre, KPJ Pahang Specialist Hospital, Darul Makmur Medical Centre, PRKMUIP Specialist Hospital and KCDC Hospital. The IIUM Medical Centre located in Bandar Indera Mahkota, is a government-funded teaching hospital managed by Kulliyyah of Medicine, International Islamic University Malaysia. For outpatient treatment, general practitioners are available at private-owned clinics which are easily accessible in most housing estates.[104] The availability of affordable advanced medical services had benefited the state directly from the booming Malaysian medical tourism.

Public health system is financed mainly through general revenue and taxation collected by the federal government, while the private sector is funded principally through out-of-pocket payments from patients and some private health insurance. There is still, however, a significant shortage in the medical workforce, especially of highly trained specialists; thus, certain medical care and treatment are available only in large towns. Recent efforts to bring many facilities to other towns have been hampered by lack of expertise to run the available equipment. As a result, secondary care is offered in smaller public medical facilities in suburbs and rural areas, while more complex tertiary care is available in regional and national hospitals in urban areas like Temerloh and Kuantan.[105]

Education

Education in Pahang is overseen by two federal ministries, the Ministry of Education responsible for primary and secondary education, and Ministry of Higher Education that is responsible for universities, polytechnic and community colleges. Although public education is the responsibility of the Federal Government, Pahang has an Education Department to co-ordinate educational matters in its territory. The main legislation governing education is the Education Act 1996. The education system features a non-compulsory kindergarten education followed by six years of compulsory primary education, and five years of optional secondary education.[106] Schools in the primary education system are divided into two categories: national primary schools, which teach in Malay, and vernacular schools, which teach in Chinese or Tamil.[107] Secondary education is conducted for five years. In the final year of secondary education, students sit for the Malaysian Certificate of Education examination.[108] Since the introduction of the matriculation programme in 1999, students who completed the 12-month programme in matriculation colleges can enroll in local universities. By Malaysian law, primary education is compulsory.[109] Early childhood education is not directly controlled by the Ministry of Education as it does with primary and secondary education. However, the ministry does oversee the licensing of private kindergartens, the main form of early childhood education, in accordance with the National Pre-School Quality Standard, which was launched in 2013.[110]

Around the time of independence in 1957, overall adult literacy of Malaya in general was quite low at 51%.[111] By the year 2000, adult literacy had increased significantly in Pahang to 92.5% and further increased to 95% ten years later in 2010 census. From these figures, urban literacy was recorded at 95% in 2000 and increased to 97.5 in 2010, while rural literacy was recorded at 90% in 2000 and increased to about 93.5% in 2010.[112]

As of 2017, there are 736 schools in Pahang, which 540 are primary and 196 are secondary schools. Included in this figure are 8 technical/vocational schools and 18 state religious secondary schools managed by Pahang Islamic Religious Department.[113][114] In addition to federal and state government-funded schools, there are a number of international private schools in Pahang. Garden International School, International School of Kuantan, and International Islamic School Malaysia are the three main international schools serving primary and secondary levels. Another notable international school is Highlands International Boarding School located in Genting Highlands that caters secondary education.[115]

Tertiary education in the state offers certificate, diploma, first degree and higher degree qualifications. The higher learning institutions consist of two major groups, public and private institutions. Public institutions includes universities, polytechnics, community colleges and teacher training institutes. While the private institutions includes private universities, university colleges, foreign branch campus universities and private colleges. Among notable public universities are Universiti Malaysia Pahang, International Islamic University Malaysia Kuantan Campus, one state campus of Universiti Teknologi MARA in Jengka, and two satellite campuses in Kuantan and Raub. Pahang is also home to private universities like DRB-Hicom University of Automotive Malaysia and Universiti Tenaga Nasional Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Campus.[116]

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 504,945 | — |

| 1980 | 768,801 | +52.3% |

| 1991 | 1,045,003 | +35.9% |

| 2000 | 1,229,104 | +17.6% |

| 2010 | 1,440,741 | +17.2% |

| 2020 | 2,064,384 | +43.3% |

| Source: [117] | ||

According to the latest national census in 2010, Pahang population stood at 1.5 million including non-Malaysian citizens, making it Malaysia's ninth most populous state.[118] In 2017, with average annual population growth at 1.61%,[58] the population number is projected to increase to 1.65 million.[2] Pahang population is distributed over a large area resulting in the state having the second lowest population density in the country after Sarawak, with only 42 people per km2.[119] In terms of age group, overall population is relatively young, people within the 0-14 age group constitute to 29.4% of the total population; the 14-64 age group corresponds to 65.4%; while senior citizens aged 65 or older make up 5.2%.[120] The ratio of males to female is the highest in Malaysia at 113,[119] with male population was recorded at 0.809 million compared to female population figure at 0.615 million.[120] As of 2010, the crude birth rate in Pahang was 17.3 per 1000 individuals, the crude death rate was 5.1 per 1000 population, and the infant mortality rate was 7.6 per 1000 live births.[101]

About 95% of the population are Malaysian citizens. Malaysian citizens are divided along ethnic lines, with 75% considered bumiputera. The largest group of bumiputera that make up 70% of Pahang population, are Malays, who are defined in the constitution as Muslims who practice Malay customs and culture. They play a dominant role politically. Bumiputera status is also accorded to certain non-Malay indigenous peoples that make up 5% of the population, in particular the aboriginal groups known as Orang Asli. Other non-Malay indigenous peoples also include ethnic Thais, Khmers, Chams and the natives of Sabah and Sarawak. 15.3% of the population are of Chinese descent, while those of Indian descent comprise 4% of the population.[118] The presence of Chinese miner-merchants was recorded since the time of the old Pahang Sultanate,[28] and the community have historically been dominant in the business and commerce community. Immigrants from India, the majority of them Tamils and began arriving in large numbers during British protectorate at the end of the 19th century. Every citizen is issued a biometric smart chip identity card known as MyKad at the age of 12, and must carry the card at all times.

In 1957, a large majority of the population resided in rural areas with urbanisation rate stood at only 22.2%.[121] The urbanisation had increased significantly but relatively at a lower rate compared to other states, owing to its large agricultural lands. The state had the second lowest urbanisation rate after Kelantan in 2010 census, with 50.5% of the population resided in urban areas and the remainder are rural dwellers.[119] By 2020, it has been targeted that the urbanisation rate would reach 58.8%.[122] Major urban centres are Kuantan, Temerloh, Bentong and Pekan, serving as Pahang main commercial and financial centres. Due to the rise in labour-intensive industries, the state has over 74 thousands migrant workers; about 5% of the population, mainly employed in agriculture and industrial sectors.[118]

Ethnicity

As a multiracial country, Malaysia is home to many ethnic groups. In 2016, it is ranked 59th most ethnically diverse countries in the world with index at 0.596. However, ethnic diversity is not equally distributed among its states and territories. Pahang is categorised as medium ethnically diverse state with 0.36 of ethnic diversity index in 2010. It is ranked 5th least diverse among Malaysian states and territories, after Terengganu, Kelantan, Melaka and Perlis. The least ethnically diverse districts are Pekan, Rompin and Temerloh (index between 0.1 and 0.39), and the most ethnically diverse districts are Bentong and Raub (index between 0.49 and 0.59) where minorities form significant proportion of the population. Ethnic diversity in Pahang was historically high, at an index between 0.5 and 0.6 in the 1970s, but showing a downward trend decades later, largely caused by outward migration, high birth rate of the majority population and the opening up of new agricultural lands particularly the FELDA settlements, that attract many immigrants from other Malaysian states.[123]

The most dominant ethnic group are Malays that make up 70% of Pahang population, who are defined in the constitution as Muslims who practice Malay customs and culture. The Malays in turn, can be further divided into several sub-ethnic groups, of which the most dominant are the Pahang Malays. Historically, the community can be found in the vast riverine systems of Pahang and are prominently featured in the state's history. There are also small Pahang Malay communities in the valley of the Lebir River in Kelantan and the upper portions of several rivers near the Perak and Selangor boundaries, descendants of fugitives from the civil war that ravaged their homeland in the 19th century.[124] The Terengganuan Malays, another east coast sub-ethnicity, are native to narrow strip of sometimes discontiguous fishermen villages and towns along the coastline of Pahang.[125] Other important Malay sub-ethnicities include the Kelantanese and Kedahans, that migrated from Kelantan and Kedah respectively, and can be found in major urban centres and agricultural settlements.

The Malays are collectively referred as bumiputera along with other non-Malay indigenous people that constitutes about 5% of the state's population. The community of Orang Asli form the most dominant non-Malay indigenous group. According to 2010 census, Pahang has the largest Orang Asli population in Malaysia with 64,000 people, followed by Perak with 42,841 people.[126] The Orang Asli in Pahang is grouped into 3 large groups; Negrito, Senoi and Proto Malay. Approximately 40% of them live close to or within forested areas, and engage in swiddening as well as hunting and gathering of forest products. Some also practise permanent agriculture and manage their own rubber, oil palm or cocoa farms. A very small number, especially among the Negrito groups, are still semi-nomadic and depend on the seasonal bounties of the forest. Due to sweeping modernisation, a fair number of them are to be found in urban areas surviving on their waged or salaried jobs. The three groups of Orang Asli can be divided further into several smaller tribes that traditionally domiciled in certain geographical part of Pahang. The Bateq tribe of Negrito group can be found in northern part of Pahang. Two Senoi tribes, Semaq Beri and Semai are also domiciled in northern Pahang. Two other Senoi tribes, Chewong and Jah Hut communities can be found in central Pahang. Meanwhile, the southern part of the state is dominated by Proto Malay tribes of Jakun, Temoq, Semelai and Temuan.[127]

The minorities consist of Chinese and Indians form collectively about 19.5% of the population. They are descendants of immigrants from China and India that came in large numbers during British protectorate to work in the mines, rubber plantations and various services sector. They are primarily concentrated in the western districts of Raub and Bentong and other urban areas.

| Ethnic Group | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010[4] | 2015[3] | |||

| Malay | 1,052,774 | 70.15% | 1,146,000 | 70.60% |

| Other Bumiputras | 73,413 | 4.89% | 83,800 | 5.16% |

| Bumiputra total | 1,126,187 | 75.04% | 1,229,800 | 75.76% |

| Chinese | 230,798 | 15.38% | 241,600 | 14.88% |

| Indian | 63,065 | 4.20% | 66,300 | 4.08% |

| Others | 6,159 | 0.41% | 7,800 | 0.480% |

| Malaysian total | 1,426,209 | 95,03% | 1,545,500 | 95.21% |

| Non-Malaysian | 74,608 | 4.97% | 77,700 | 4.79% |

| Total | 1,500,817 | 100.00% | 1,623,200 | 100.00% |

Religion

The constitution of Pahang established Islam as a state religion, but grants freedom to manifest other religions in its territory. In the areas of family law and religious observances, the Sharia law are applied to the Muslims and came under the jurisdiction of the Sharia court. The jurisdiction of Syariah courts is limited to Muslims in matters such as marriage, inheritance, divorce, apostasy, religious conversion, and custody among others. No other criminal or civil offences are under the jurisdiction of the Shariah courts, which have a similar hierarchy to the Civil Courts. Despite being the supreme courts of the land, the Civil Courts do not hear matters related to Islamic practices.[129] Matters related to the enforcement of the Syariah law falls under the jurisdiction of the Jabatan Agama Islam Pahang ('Pahang Islamic Religious Department'). Pahang's constitution empowers the Sultan as the head of Islam and Malay customs in the state. State council known as Majlis Ugama Islam dan Adat Resam Melayu Pahang ('Council of Islam and Malay Customs of Pahang') is responsible in advising the ruler as well as regulating both Islamic affairs and adat. Sunni Islam of Shafi'i school of jurisprudence is the dominant branch of Islam,[130][131] and became the basis of Sharia court rulings and Sharia law passed in the Pahang State Legislative Assembly.

According to the Population and Housing Census 2010 figures, ethnicity and religious beliefs correlate highly. Approximately 74.9% of the population practice Islam, 14.4% practice Buddhism, 4% Hinduism, 2.7% non-religious, 1.9% Christianity.[128]

The Malaysian constitution defines what makes a "Malay", considering Malays those who are Muslim, speak Malay regularly, practise Malay customs, and lived in or have ancestors from Malaysia and Singapore.[132] All Malays are therefore necessarily Muslim. Statistics from the 2010 Census indicate that 89.4% of the Chinese population identify as Buddhists, with significant minorities of adherents identifying as Christians (6.7%), Chinese folk religions (2.8%) and Muslims (0.4%). The majority of the Indian population identify as Hindus (90.3%), with a significant minorities of numbers identifying as Muslims (3.6%), Christians (2.5%) and Buddhists (2.3%). The non-Malay bumiputera community are predominantly Atheists (51.9%), with significant minorities identifying as Muslims (11.8%) and Christians (11.7%).[133]

- Religious sites in Pahang

Languages

The official and state language of Pahang is Malaysian,[134] a standardised form of the Malay language.[135] The terminology as per federal government policy is Bahasa Malaysia (literally "Malaysian language")[136] but in the federal constitution continues to refer to the official language as Bahasa Melayu (literally "Malay language").[137] The National Language Act 1967 specifies the Latin (Rumi) script as the official script of the national language, but allow the use of the traditional Jawi script.[138] Jawi is still used in the official documents of state Islamic religious department and council, on road and building signs, and also taught in primary and religious schools. In 2018, the then Regent of Pahang in a royal decree, expressed his wish for a wider use of Jawi on road signs, business premises, office signs, government agencies and all state education offices in the state. Among the earliest response to the royal decree was by Kuantan Municipal Council that announced enforcement by 2019.[139] English remains an active second language, with its use allowed for some official purposes under the National Language Act of 1967.[138]

The Malay language spoken in Pahang can be further divided into several varieties of Malay dialects. Pahang Malay is the most dominant Malay dialect spoken along the vast riverine systems of Pahang, but it co-exists with other Malay dialects traditionally spoken in the state. Along the coastline of Pahang, Terengganu Malay is spoken in a narrow strip of sometimes discontiguous fishermen villages and towns. Another dialect spoken in Tioman Island is a distinct Malay variant and most closely related to Riau Archipelago Malay subdialect spoken in Natuna and Anambas islands in the South China Sea, together forming a dialect continuum between the Bornean Malay with the Mainland Peninsular/Sumatran Malay. Kelantanese and Kedahan, along with other Malay dialects are also spoken by immigrants from other Malaysian states.

Pahang is also home to majority of Orang Asli languages, mostly belong to Aslian branch of Austroasiatic such as Semai, Batek, Semoq Beri, Jah Hut, Temoq, Che Wong, Semelai (although recognised as "Proto-Malay"), Temiar and Mendriq. Besides Austroasiatic, Proto-Malay languages that is a branch of Austronesian are also spoken, mostly Temuan and Jakun.

Malaysian Chinese predominantly speak Chinese dialects from the southern provinces of China. The more common Chinese varieties in the country are Mandarin, Hokkien, Hakka, Cantonese, Hainanese and Fuzhou.

Tamil is used predominantly by Tamils, who form a majority of Malaysian Indians.

Culture

As a less ethnically diverse state, the traditional culture of Pahang is largely predominated by the indigenous culture, of both Malays and Orang Asli. Both cultures trace their origin from the early settlers in the state that consist primarily from both various Malayic speaking Austronesians and Mon-Khmer speaking Austroasiatic tribes.[140][141] Around the opening of the common era, Mahayana Buddhism was introduced to the region, where it flourished with the establishment of a Buddhist state from the 5th century.[19] Malayic cultures flourished during Srivijayan era, and Malayisation intensified after Pahang was established as a Malay-Muslim Sultanate in 1470. The development of many Malay-dominated centres in the state, drew some of the natives to embrace Malayness by converting to Islam, emulating the Malay speech and their dress.[142] Pahang Malays share similar cultural traits with other sub-groups of Malay people native to the Malay peninsula. They are in particular closely affiliated to peoples of the east coast of the peninsula like Thai Malays, Terengganuan Malays and Kelantanese Malays.[143]

Unlike the relatively homogeneous Malay culture, the cultural features Orang Asli are represented by significantly diverse tribal identities. Prior to the 1960, the various indigenous groups did not consciously adopt a common ethnic marker to differentiate themselves from the Malays. The label 'Orang Asli' itself was historically came from the British. Each tribe has its own language and culture, and perceives itself as different from the others. This micro identity was largely derived spatially, from geographical area they traditionally settled. Their cultural distinctiveness was relative only to other Orang Asli communities, and these perceived differences were great enough for each group to regard itself as unique from the other.[144]

In 1971, the government created a "National Cultural Policy", defining Malaysian culture. It stated that Malaysian culture must be based on the culture of the indigenous peoples of Malaysia, that it may incorporate suitable elements from other cultures, and that Islam must play a part in it.[145] It also promoted the Malay language above others.[146] This government intervention into culture has caused resentment among immigrant communities who feel their cultural freedom was lessened. Both Chinese and Indian associations have submitted memorandums to the government, accusing it of formulating an undemocratic culture policy.[145]

Arts

Traditional visual arts was mainly centred on the areas of carving, weaving, and silversmithing,[147] and ranges from handwoven baskets from rural areas to the silverwork of the Malay courts. The Malays had traditionally adorned their monuments, boats, weapons, tombs, musical instrument, and utensils by motives of flora, calligraphy, geometry and cosmic feature.[148] Common artworks included ornamental kris, beetle nut sets, and woven batik and songket fabrics. The Malay handloom industry traced its origin since the 13th century when the eastern trade route flourished under Song dynasty.[149] By the 16th century, the silk weaving industry in Pahang had perfected a style called Tenun Pahang, a special clothing fabric used in the special traditional Malay costumes and attires of Pahang rulers and palace officials.[150] In addition to silk weaving, Batik weaving has been part of the small cottage industry in the state. Although not as popular, Pahang batik has, nevertheless, thrived as a small industry in the periphery of the fame of the Terengganu and Kelantan batik.[151] Over the centuries, a distinctive style of Baju Kurung was developed in Pahang, commonly known as Baju Kurung Pahang or Baju Riau-Pahang, or sometimes called Baju Turki. This is a long gown styled dress, cut at the front with 7 or more buttons and worn with a sarong.[152][153]

Traditional Malay music is based around percussion instruments,[154] the most important of which is the gendang (drum). There are at least 14 types of traditional drums.[155] Drums and other traditional percussion instruments and are often made from natural materials.[155] Pahang traditional music may be classified as a type of old oral literature in poetic forms, which exist in several different genres. The most notable one is a set of 36 songs in Indung dance.[156] Another significant genre is a set of healing songs in Saba dance commonly performed using shamanistic charms[156] There are other genres exist, among others are songs from traditional dances of Mayang', Limbung and Lukah, songs from Dikir Rebana, Berdah, Main Puteri and Ugam performances, as well as Lagu dodoi (lullabies), Lagu bercerita (story telling songs) and Lagu Permainan (children game songs).[157][158] Other popular Pahang folk songs included; Walinung Sari, Burung Kenek-Kenek, Pak Sang Bagok, Lagu Zikir, Lagu Orang Muda, Pak Sendayung, Anak Ayam Turun Sepuluh, Cung-Cung Nai, Awang Belanga, Kek Nong or Dayang Kek Nong, Camang Di Laut, Datuk Kemenyan Tunggal, Berlagu Ayam, Walida Sari, Raja Donan, Raja Muda, Syair Tua, Anak Dagang, Puteri Bongsu, Raja Putera, Puteri Mayang Mengurai, Puteri Tujuh, Pujuk Lebah, Ketuk Kabung (Buai Kangkong) and Tebang Tebu.[159]

Forms of ritual theatre amongst the Pahang Malays include the Main Puteri,[160] Saba[156] and many forms of Ugam performances. There are Ugam Mayang, Ugam Lukah, Ugam Kukur and Ugam Serkap, all of which involve trance and serve as agents of healing by a Bomoh. Ugam Mayang is also popularly known in Terengganu and the rest of Malaysia as Ulek Mayang.[161] One of the most popular dance theatre is Mak Yong, which is also performed in Kelantan and Terengganu.[162] Popular dance forms also include Joget Pahang( a local style of Joget),[163] Zapin Pekan and Zapin Raub (local styles of Zapin),[164] and Dikir Pahang or Dikir Rebana (a modified and secularised form of dhikr or religious chanting, also performed in Kelantan as Dikir barat).[156] Dikir Rebana which is further divided into Dikir Maulud and Dikir Berdah, has many songs played by a group of 5 to 7 people and was historically performed in the royal court. Pahang performing arts also include some native dance forms like Limbung, Labi-Labi, Pelanduk and Indung.[165] A distinct form of gamelan adopted from the Javanese culture during the time of Johor Empire, known as Malay Gamelan or Gamelan Pahang, forms the main musical ensemble heritage in the state and patronised by royal court of Pahang since the 19th century.[166]