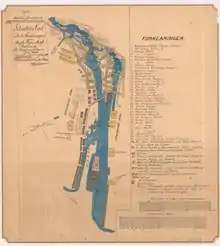

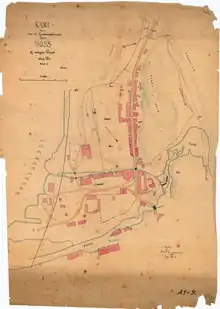

Moss Jernverk ("Moss Ironworks") was an ironwork in Moss, Norway. Established in 1704, it was for many years the largest workplace in the city, and melted ore, chiefly from Arendalsfeltet (a geologic province in Norway). With power from the nearby waterfalls it manufactured many different products. From around the middle of the 1700 century the works were the leading armory in the country and produced hundreds of heavy iron cannons. The first rolling mill in Norway was also located here.

Amongst Moss Jernverk's owners were many of Norway's best-known businessmen, including Bernt Anker and Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg. Under Anker's management it became a much visited attraction for early travellers to Norway. The administration building is best known for being the site where the Convention of Moss was negotiated in August 1814.

In the middle of the 19th century Moss Ironworks met increased competition from Swedish and English ironworks; consequently it closed down in 1873. It was sold for 115,000 speciedaler in 1875 and the area was taken over by the company M. Peterson & Søn, which used it until it went bankrupt in 2012.

Background and establishment

Iron has been extracted and processed in what today is known as Norway for over two thousand years.[1] The first iron producers used Bog iron, which then was processed by what Norwegians know as "jernvinne". Such production of iron was however local and on a small scale – much effort was needed to extract small quantities of iron.

In the 16th century the interest for excavating ore grew in Europe and the foundation for modern knowledge of mineralogy was established by the German Georgius Agricola.[2] In the kingdom of Denmark-Norway iron ore was found in the Norwegian part of the country. In the southern part of Norway the richest deposits were in the Arendalsfeltet around the city of Arendal; however, owing to the need for large amounts of wood to produce charcoal for the blast furnace and power from water falls for powering the bellows, ironworks were often established at other places than close to the iron ore mines. [note 1] By the city of Moss there was easy access to power from waterfalls; there were large woods in the vicinity and the location by the Oslofjord made receiving ore and shipping out the various produced goods easy.

The Danish civil servant and businessman Ernst Ulrich Dose started in 1704 with establishing an ironwork at Moss,[3] and in the same year the Dano-Norwegian king Frederick IV visited Moss twice,[4] events that were positive for Dose's undertakings. In addition to buying land and claiming rights to power from the waterfalls and access iron ore, the projected ironworks received "cirkumferens", an area with a radius of around 25 kilometer where the farmers had to produce and deliver charcoal and other raw material to the ironworks. In November 1704 Moss and its surroundings were inspected by experts from the oberbergamt (the state authority responsible for mines and minerals) in Kongsberg and a letter of privilege was issued on 6 December that year. In the letter various privileges were stated; for the surrounding woods, area for the ironworks, water, access by road, iron ore, freedom from customs and several other points.

Workers were exempted from taxes and military service; they were to be tried by "bergretten" (a special court for miners, residing in Kongsberg), and if needed skilled workers could be recruited from abroad, regardless of what nation they belonged to.[note 2] By its extensive royal privileges Moss Ironworks, when it was established, was close to being a state within the state.[note 3]

Dying in 1706, the prosperous Ernst Ulrich Dose did not live to see Moss Ironworks in full operation.

First years and war

After Ernst Ulrich Dose's death Moss Jernverk was auctioned off and in May 1708 sold to Jacob von Hübsch (3/4) and Henrich Ochsen (1/4).[5] The timing was good, war was close and the ironworks was close to the three large fortresses in the south-eastern part of Norway: Akershus, Fredrikstad and Fredriksten. Hübsch stated in 1713 that he bought the unfinished ironworks to supply the armed forces with cannons, ammunition and rifles. War broke out in 1709 and in 1711 there was an attack into Sweden, supplied by Moss Jernverk with ammunition, cannonballs in iron. The campaign was short, without any use of ammunition and Hübsch had severe difficulties with the payment.[6]

One of the privileges Moss Jernverk received when it was established was exemption from Tithe for three years after the blast furnace was in continuous use. The work to re-establish the tithing was commissioned at Kongsberg in 1712 by the generalkrigskommissær H. C. von Platen (the civil servant responsible for defence matters), but owing to lack of charcoal the blast furnace was only working for shorter periods.[note 4] The local farmers were bound to supply 4733 lester (one lest was around 2 m³) charcoal every year, but in 1714 the ironworks lacked 24,600 lester. The duty to deliver charcoal was quite clearly an extra tax and the farmers tried to avoid it.[note 5] Owing to the initial production problems the ironworks was given the exemption until 1715.

At the latter stage of the Great Northern War Norway was invaded in 1716; the city of Moss and the ironworks were taken by Swedish forces on 17 March. On 26 March the Swedish forces were expelled, but the day after the Swedes again took possession of the city and held it for five weeks, and the ironworks was looted. The war years were difficult for the ironworks: in addition to looting the farmers were busy with transporting goods for the forces and had little time for producing and delivering charcoal. While the other Norwegian ironworks made good money from the war, Moss Jernverk and its main owner Hübsch fared badly.[note 6] Owing to the various difficulties Hübsch petitioned the king for additional years with the exemption and was granted until 1722, from 1723 Moss Jernverk had to pay 300 riksdaler and from 1724 the same as other Norwegian ironworks, which amounted to 400 riksdaler each year.

Post-war years and change of ownership

Jacob von Hübsch died in October 1724 and his widow, Elisabeth Hübsch (née Holst) took over, a heavy burden for a single woman with seven children. In order to better supervise the business she moved with her children from Copenhagen to Moss. The competition from cheap Swedish iron was devastating and many Norwegian ironworks closed down their production.[7] Elisabeth Hübsch had to take large loans to run Moss Jernverk and her creditors became aggressive. Even though Norwegian ironworks enjoyed a monopoly in exporting iron to Denmark from 1730, the economy of Moss Jernverk was still strained.[8]

The ironworks minority owner, the civil servant Henrich Ochsen, repeatedly had to cover various expenses, but in 1738 his patience with the widow ended. Henrich Ochsen sent his attorney Jens Bondorph from Copenhagen to take control over the business. Elisabeth Hübsch tried her best to fight back and in the court archives about the case the situation and the debt of the business is well covered.[9] On 21 January 1739 the oberbergamt on Kongsberg ruled that Jens Bondorph was given the right to control the part of Moss Jernverk that belonged to the widow, until the case was settled. After several years of court proceedings Moss Jernverk was auctioned off and Henrich Ochsen took control of the whole business.[10]

Raw materials, the ironworks and the products

An ironworks in the 18th century was capital intensive heavy industry of great importance for the country and there were several challenges to achieve a satisfying production. At the court proceedings in 1738 it was recorded what Moss Jernverk had of assets and together with supervisor Knud Wendelboe's report it gives a good overview of the business. In the sections below the various activities at the premises are described, from the establishment in 1704 to the close-down in 1874.

Iron ore

The mines that, owing to Moss Jernverk's privileges, were obliged to deliver iron ore, could not supply sufficient amount, so in 1706 the manager Peter Windt secured that Løvold mine at Arendal should deliver 1,000 barrels iron ore each year. The quality of the iron ore was so mixed that there were court proceedings, resulting in the requirement that two knowledgeable miners should control the quality of the iron ore. The mines around Arendal were the most important for the Norwegian ironworks, as they delivered around 2/3 of all iron ore.[note 7] Even though the most important mines were located some distance from the ironworks, the transport was not expensive, as the iron ore was sent by boat.[note 8]

In a 1723 report from Moss Jernverk the manager Knud Wendelboe wrote that they had to collect iron ore for 2–3 years to have one production period.[11] In 1736 the entity had some minor mines around Moss and the larger mines at Østre Buøy, Vestre Buøy, Langsæ and Bråstad in Agder, part of the Arendalsfeltet, supplying iron ore. The management at that time was however not vigilant enough in seeing that the mines supplied iron ore of the quality needed.[12]

In 1749 Weding mines at Arendal is also mentioned; the iron ore from that mine stood out as versatile and was classified as the best Moss Jernverk received. In addition to the mines around Arendal, Skien was a center for the mines supplying Moss Jernverk and several mines were developed there.[13] The ironworks had agents in Skien and Arendal that looked after its interests, paid the miners and took care of seeing that the licenses for using the mines (mutingsbrev) were renewed. In the long period that Lars Semb was manager at Moss Jernverk he traveled almost yearly to the mining areas and he subsequently stayed with the local agents.[14]

Charcoal

Moss Jernverk was totally dependent on charcoal that the surrounding farmers produced. In the spring of 1720 the farmers had a debt of 28,000 lester. Manager Knud Wendelboe at the ironworks stated that for the years 1709–1723 it should have received 70,995 lester, while the actual amount delivered was 37,233 lester, a debt of 33,726 lester charcoal.[15] The debt was due partly to lack of wood, partly to the war, but also to the farmer's reluctance to fulfil their duty to deliver charcoal to Moss Jernverk.[16]

The lack of charcoal continued under Ancher & Wærn's ownership of Moss Jernverk, even though they paid better than other ironworks and gave bonus to those that delivered more than requested. The main reason for dismal quantities delivered was that producing charcoal almost always was less profitable than other use of the timber.[17] Under his ownership, Bernt Anker tried to get the authorities' permission to have a certain quantity charcoal delivered from each farm.

Even the mighty Bernt Anker was not successful in this and it was clear that the authorities did not want to press the farmers too hard to keep their duty of delivering charcoal.[note 9] For the total time-span of 1750–1808 Moss Jernverk received an average of 6,000 lester charcoal each year, while the need for full production mandated twice the quantity.[note 10] The majority of the charcoal was burned and delivered by the farmers in the winter; each transport by horse took only one lest so there were many trips between the various farms and the ironworks until everything was delivered.[18]

Water

The manager Knud Wendelboe stated in his 1723 report that Moss Jernverk was hampered by the lack of water. This was partially caused by the nonexistence of a dam that could collect flood water from the lake Vansjø and partly by the other users of water from the falls (mills and sawmills) using more than their assigned share of the available water. If the water supply to run the blast furnace belches stopped, the oven would quickly stop and huge losses would occur.[19]

During large construction works in 1750 Moss Jernverk got a large head race (Norwegian: vannrenne) that passed over the main road; the previous ran under the road. The head race was 8–9 feet wide, 6 feet deep and the height (fallhøyden) was 48 feet.[20] After the large works, lack of water was a minor problem compared to the early years of the ironworks, but during an unusual drought in 1795 work was extended to the building of dams in and above Krapfos, as the manager Lars Semb thought should have been done for many years. Within Moss Jernverk (not included mills and sawmills) there was, around 1810, a total of 24 water wheels, some of them quite large.[21]

The Ironworks

The ironworks consisted of a large number of buildings on the northern side of the river from the Moss waterfalls. The building with the blast furnaces was the main building. Within this building the two blast furnaces were situated, each 31 feet high, but only the easternmost was in use. In addition to the blast furnaces there was heavy equipment; a winch was used to lift large metal pieces. On the eastern side of the building for the blast furnaces was a building where the molten iron was formed into various shapes. There was also a house with a water-powered hammer that crushed the iron ore. There were two storehouses for charcoal, the westernmost was around 56 x 25 alen (around 550 square meter) while the easternmost measured 45 x 20 alen (around 350 square meter).[22]

The fire risk was substantial; hence, there was also a house with a double fire pump, two hoses. East of the house where the molten iron was shaped there was a forge (kleinsmie) where delicate forging was done. By the seashore there was a wharf with a large storage building. The owner of Moss Jernverk lived in a large building with 9 living rooms, on two floors. In another two story house there were offices. In addition there was a variety of other buildings, stables for horses, barn, living houses for workers and more. The water saw by the bridge was of special importance for Moss Jernverk, where it was licensed to cut timber for new buildings, repair etc. The ironworks could cut up to 12,900 logs on this saw; sale of wood outside Moss Jernverk was strictly forbidden and would be punished with confiscation.[23]

In addition to various expansions and renewals during the 170 years of Moss Jernverk's operation, sections of the ironworks had to be rebuilt after fires. In the 1760s the expensive water-powered hammer burned down, but it was rebuilt in 1766.[24]

In several areas Moss Jernverk was technologically advanced: it was the first ironworks in Norway with tall blast furnaces,[25] cannon production, production of nails. It also had the first rolling mill in Norway, built in 1755 after English design and it cost the considerable amount of 12,000 riksdaler.[26]

The products

When Moss Jernverk was established it was planned by the entrepreneurs to produce ammunition. According to the manager Wendelboe most of the iron produced until 1723 was used for grenades and bullets – only a minor part was iron that was further processed by the water-powered hammers. In an overview from Landetatens Generalkommissariat (the army,[note 11]) from 2 May 1720 the following overview was presented:

| Time of delivery | Amount | Type of ammunition |

|---|---|---|

| 18 June 1714 | 2 000 | 24-pound Round shot |

| 22 March 1715 | 3 000 | 24-pound Round shot |

| 5 330 | 10-pound grenades | |

| 31 January 1716 | 800 | 200-pound grenades |

| 9 000 | 100-pound grenades | |

The price for the heavy ammunition was given as 11,5 riksdaler pr skippund (around 160 kg) while the price for the smaller grenades was 14,5 riksdaler, in total rather large sums.[27] According to the contract from 1716 the ironworks until 1730 delivered around 2,500 skippund worth around 30,000 riksdaler. In 1713 Moss Jernverk also produced 1,000 rifles.[28]

In addition to the military production there was a smaller and varied production for civilian purposes. Moss Jernverk manufactured anvils, saw blades, saucepots, waffle irons and more. The ironworks also made specially designed products; an example was an oven for producing sugar for a sugar refinery in Fredrikshald (Halden) in the 1750s. In the 19th century clothes irons were also produced.[29] During Bernt Anker's time iron for drums was a major product, being also exported.[note 12]

Moss Jernverk's production of iron ovens is of particular interest, partly owing to their current existence, and partly owing to their being designed by talented artists. The Norwegian art historian and riksantikvar Arne Nygård-Nilssen maintains that the ovens were designed by Torsten Hoff, a renowned designer of ovens, who established himself as a sculptor in Christiania in 1711, working there until his 1754 death.[30]

After taking over Moss Jernverk, Ancher & Wærn did also invest in the production of ovens and through one of their connections in Copenhagen they recruited Henrik Lorentzen Bech (1718–1776) to move to Moss. He worked on designs for iron ovens there for around one year, and yet again in 1769.[note 13] From Henrik Lorentzen Bech's last working period at Moss Jernverk three main designs are known; "Medaljongen" (the medallion), "Herkules" and "Altertavlen" (the altar piece), the ironworks used these very popular designs for many years.[31]

| Caliber | København | Rendsborg | Glückstad | Christiania | Fredrikstad | Fredrikssten | Christiansand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 / 12 / 6-pound | 42 / 171 / 5 | 9 / 59 / 0 | 11 / 29 / 0 | 0 / 34 / 0 | 10 / 37 / 0 | 8 / 20 / 0 | 0 / 5 / 0 |

In addition to the cannons listed in the table above a total of 29 12-pound cannons were produced, that sank with their ship during transport in 1759.[32][33] The quality of the cannons that were produced during Bernt Anker's ownership been good according to the manager Lars Semb; none of the guns had cracked during testing for 30 years.[34] During Ancher & Wærn's ownership of Moss Jernverk the cannons were labelled "AW", while later on "MW" was used. A common inscription on the cannons was "Liberalitate optimi" (by the sovereign's most kind generosity), which pointed to the privileges and the large loan from the state.[35]

Moss Jernverk manufactured cannons up to 36-pound size, but also 1/8-pound, which were considered toys. In 1789 there were suspicions regarding 18-pound and 12-pound cannons' quality – test firing confirmed that the cannons were inadequate. This resulted in the state changing to Swedish ironworks for purchasing cannons, with the imminent result that the cannons from Moss were eventually phased out.[36] As late as during the First Schleswig War (1848–1850) the fortress at Fredericia in Denmark was defended with cannons from Moss Jernverk.

A small society

Moss Jernverk was a small independent society, residing north of the city of Moss. The manager was usually called steward (forvalter); the first was Niels Michelsen Thune, and his reign began at the start of the ironworks and lasted until 1716. In addition to Thune a man named Peder Windt was director in the years 1706–1708. After Thune the next steward most probably was Knud Wendelboe. He compiled several extensive reports regarding Moss Jernverk. After the auction in 1738 Jens Bondorph from Copenhagen took charge, but when Henrich Ochsen sold Moss Jernverk, the steward's name was Wichman.

The workers at Moss Jernverk were more anonymous, but typically for the advanced technology an ironworks in that age was, most of them came from other countries – their names tell of Swedish and German origin. How important the skilled workers were for the ironworks is shown in a letter Jacob von Hübsch wrote to the king on 27 December 1719 in which he states that, as the Great Northern War still was fought and the ironworks was idle, he still had to pay his workers in order to keep them.[37]

In the 1730s there was a lack of skilled workers and the workers seemed to exploit that by striking and demanding higher wages during the auction in 1738. The conditions for most of the workers were all the same, poor. Carl Hübsch wrote in 1738 that Moss Jernverk did not keep any overview of the workers that built houses on their premises, as they anyway were so poor that no rent could be extracted from them.[38]

The society around the ironworks had a strained relationship on several levels with the city of Moss. One contested privilege was the duty-free import of food, whereas the citizens of Moss had to pay consumption tax for all goods that passed the city border. Another was the use of the water from the waterfalls and the bridge crossing the waterfalls, the maintenance of it was the responsibility of the town, which they felt was unjust. In addition to this came the jurisdiction. Moss Jernverk had the privilege to judge its workers, with the bergrett at Kongsberg as appellate court, something the local magistrate was much opposed to.[39] In reality the cases were almost always solved locally.[note 14] Two young boys that had stolen potatoes from a farm were punished by their parents by flogging in the ironworks jail, something the parents were satisfied with and further on: "humbly request that the punishment will not be extended and that the kids will be relieved of having to travel to Kongsberg to be punished there".[40]

The vicar Christian Grave, of Rygge and Moss, did not hold Moss Jernverk in high esteem: a statement from him in 1743 says the following:

"At Moss City lies Mosse Jernværk owned by Hr. Stiftsamtmand Ochsen from Copenhagen, who has different from other works owner in Norway the self acquired freedom against the Oberbergamt's rules, that he no gifts give to the church."[41]

The ironworks also had a huge demand for unskilled labor and many women worked there, one of them was Thore Olsdatter malmkjerring (malmkjerring could be translated as ore woman) that were rolling slag, earth and charcoal for 10 shilling a day. Only regarding the church the workers were subject to the local administration. They were omitted from military service, but in times of unrest they established their own unit.[42] In 1786 Moss Jernverk gave permission for two innkeepers to establish themselves within the premises, after strict rules and a yearly fee that were given to the poor within the ironworks. The innkeepers were forbidden to sell liqueur with mortgage in food; late night parties, card games or dance were also forbidden and the inns had to close at 10 in the evening.[43]

The manager Lars Semb wrote in 1809 that the school for the workers' children was established some 40 years erstwhile, around 1770. Before that time the children had attended school in the city of Moss. From other sources it is however known that Moss Jernverk as early as in 1758 employed the teacher Andreas Glafstrøm paying him 6 riksdaler a month. In 1796 the ironworks had an advertisement for a new teacher and in it, it was written that he should: "show good references regarding his competence and knowledge in teaching children in reading, writing and math."[44]

From the end of the 18th century Moss Jernverk had a fund for education of the children and care for the poor (skole- og fattigkasse), each of the workers contributed around 2% of their pay for this and they also received free medical care and drugs, but only for themselves, not the rest of the family. In 1790 a woman from the ironworks was sent to Copenhagen to be educated as a midwife. She worked as a midwife both at Moss Jernverk and in the surrounding area until 1816.[note 15]

The ironwork's fund for poor gave a small allowance for widows, children and exhausted workers, mainly as housing and food. It seems like the management of Moss Jernverk was against firm rules for the support, it should be given out as gifts, and Bernt Anker was fond of such gestures.[45] The number of poor varied, in 1820 the manager Lars Semb estimated there were 30. The many miners working for Moss Jernverk had no obligations or rights in funding from the ironworks, but they were usually taken care of anyway.

After the 18th century the number of foreign workers at Moss Jernverk was reduced. In 1842 there were 270 persons on the ironworks, among them eight Swedes and two Germans, the manager Ignatius Wankel and his brother Frantz. In 1845 many of the workers at the ironworks joined the temperance movement in Moss and the year after the number of workers in the association had risen to 30. The workers were also active in the early Norwegian labor movement (Thranebevegelsen). A local chapter was established during Marcus Thrane's visit to the city on 16 December 1849.[46]

Moss Jernverk owned by the Anker family

Ancher & Wærn

%252C_located_at_the_old_administration_building.jpg.webp)

%252C_located_at_the_old_administration_building.jpg.webp)

Henrich Ochsen sold Moss Jernverk in 1748[note 16] for 16 000 riksdaler[note 17] to Erich Ancher and Mathias Wærn, both were businessmen from Fredrikshald, where they had large businesses manufacturing tobacco and soap.[47] There could have been several reasons for Ancher & Wærn buying the ironworks, it was prestigious, it diversified the firm which made it less vulnerable in downturns, the custom's policies could be changed so import of goods from Sweden would be more expensive, but the most important reason was probably the potential for production of armaments.[48]

Moss Jernverk was in a poor condition when Ancher & Wærn bought it and the companions had to invest heavily in order to produce large cannons. They wrote to Landetatens Generalkommissariat (the state defense office) as early as April 1749 regarding establishing a cannon foundry at the ironworks. King Frederick V was positive, but according to Ancher's reports the breakthrough happened during the king's visit to Norway in the summer of 1749.[49] The king visited Erich Ancher in Fredrikshald and visited Moss three times, so it is obvious that the king both inspected Moss Jernverk and was introduced to the plans for producing armaments.[50]

During the Autumn of 1749 the application from Ancher & Wærn regarding privileges for production of cannons was reviewed by Landetatens Generalkommisariat in Copenhagen, supported by the firm's representative Johan Frederik Classen. On 5 November Ancher & Wærn received privilegium exclusivum, a 20-year-long exclusive right to manufacture iron cannons and mortars. The details in the contract were established on 7 February 1750.

Among the many clauses in the contract was an advance of 20,000 riksdaler (14,000 at once and 6,000 after casting the first cannons) and the demand that two 12-pound cannons should be manufactured and successfully tested before the total advance was released. Each year at least 20 18-pound cannons and 30 12-pound cannons were to be tested by skilled artillery officers before deliverance. The price of the cannons were set to be 12 riksdaler and 48 skilling for each skippund (one skippund was around 160 kg).[51]

The cannon production started already in 1749. Two cannons were cast, but both was turn during the test shooting.[52] During the spring and summer of 1750 the ironworks was refurbished and expanded. Workers were sent abroad to learn how to cast cannons and new workers were recruited from abroad. Cannons of smaller size were manufactured but casting of 12 and 18-pound cannons for the test shooting were in limbo due to the constant lack of charcoal, for the production of such large pieces both blast furnaces were needed. During the winter and spring of 1751 additional problems surfaced and the two first 12-pound cannons were not ready for test shooting before the end of the year. On 18 December Colonel Kaalbøll came down from Christiania to be present at the test shooting, the result was however that both cannons were damaged by the largest charge. The ironworks blamed lack of skilled workers and in a letter dated 14 April 1751 Mathias Wærn asked his brother Morten Wærn, at that time in traveling in France, to try to recruit a worker skilled in casting cannons.[53]

Erich Ancher sent a long letter to the authorities in January 1752, regarding the various problems with manufacturing cannons and with possible solutions. The cannons should be more solid, with less arbitrary testing and a standing, rent free advance, of 50,000 riksdaler. If the authorities in Copenhagen so wished the casting of cannons could be terminated, it was done for the sake of the country. On 30 August 1752 a royal decree was issued, granting Moss Jernverk an expanded advance, mortgaged in the premises and dependent on a successful test shooting, now in Copenhagen.[54]

On 17 April 1753 two 12-pound cannons from Moss Jernverk were tested in Copenhagen, one was damaged while the other was successful. To receive sufficient deliveries of charcoal the ironworks tried to expand the area that had to deliver and on 27 August 1753 a commission was gathered in Moss to question such an expansion.[note 18] By a royal decree dated 20 May 1754 the ironworks current area was confirmed, there were no expansion and the area assigned when the ironworks was established was unchanged until Moss Jernverk closed down.[55]

The negative reply and many other problems made Ancher send a prolonged petition to the king himself, dated 28 July 1754, where he gave a thorough description of all the troubles Moss Jernverk have had in establishing production of cannons.[56] The petition had the following sigh:

- "How many times have we not wished never to have got the whim of casting cannons?"[57]

After a lengthy report Ancher concluded the petition to the king in asking for a larger cirkumferens (area where farmers were obliged to deliver charcoal), remission of the tithe and that the ironworks should receive damaged cannons as they could be melted and the iron could be reused. The king decided on the petition in November 1754, damaged cannons would be returned, but largely the answer was 'yes' to minor demands and delay regarding the important ones. From 1755 the casting of cannons gradually improved. Even though there was not cast a single cannon in 1756 that was accepted, the fight between the owners of Moss Jernverk and the authorities was about to expire.[58]

Conflict between Ancher & Wærn

While Erich Ancher lived in Fredrikshald (today named Halden) and looked after the partner's business there, Mathias Wærn were living in Moss and managing Moss Jernverk. It is plausible that Ancher blamed Wærn for the various problems with casting cannons, so the business in Fredrikshald was sold and Ancher moved to Moss. The total number of cannons delivered under Wærn's reign in the years 1749-1756 was not more than 32.[59] The ironworks debt when Ancher moved there was estimated at around 150,000 riksdaler.[60]

Moss Jernverk seemed to be in a better condition under the management of Erich Ancher. In the years 1757-1759 were cast 86, 99 and 106 pieces of 12-pound cannons without faults, but not before 1760 did the ironworks manage to produce a significant number of 18-pound cannons.[61] Ancher sent his two sons (Carsten Anker og Peter Anker) abroad to study. In Glasgow they were given the honor of being honored citizens of the city and the well known professor Adam Smith wrote approvingly of them.[note 19] At the Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg in Freiberg in Germany the two young Norwegians got a thorough education, preparing them for the family business.[62]

The relationship between Erich Ancher and Mathias Wærn deteriorated after Ancher moved to Moss and in 1761 Ancher petitioned the king for a broker that could divide the company between the two of them. The petition was accepted on 5 June 1761, with a preliminary agreement ten days after.[note 20] Wærn did however immediately distance himself from the settlement and an extended legal process started where several prominent persons got involved, among them the renowned lawyer Henrik Stampe.[63] The dispute between the two business partner was finally settled in favor of Ancher by the bergamtsretten in 1765, and the final settlement between the two was signed 17 March 1766. From that date Erich Ancher was the sole owner of Moss Jernverk.[note 21] Moss Jernverk was at this time well run and got a favorable review by a well known French expert on ironworks.[note 22]

During the 1760s the orders for cannons decreased, Denmark-Norway's state finances were dismal, which was to inflict Moss Jernverk hard as it was dependent on the armament production for the state.[64] The ironworks was heavily indebted and Erich Ancher was dependent on his brother Christian and after his death his brother's company, Karen sal. Christian Anchers & Sønner.[65] In connection with the final settlement with Mathias Wærn it was necessary for Erich Ancher to issue a mortgage bond which later would cause him much trouble.[note 23]

Due to the mortgage bond Ancher had to forgo the jurisdiction of the bergamtsretten and submit the company to the jurisdiction of the city of Moss. A lot of assets were also mortgaged. Moss Jernverk also achieved freedom from tithe for the years 1765–1770, it did however not make a large difference as it was a compensation for a water hammer works that had burned down.[66] During the 1770s Erich Ancher's debt problems with the ironworks were steadily more serious, his properties were successively mortgaged or sold off, until he at last had to surrender and sell Moss Jernverk to his cousins Bernt and Jess Anker.[67]

Bernt and Jess Anker (1776–1784)

With its new owners, the brothers Bernt and Jess Anker, Moss Jernverk got a much improved financial situation.[68] The two brothers all the same tried to get as good conditions as possible from their main customer, the kingdom of Denmark-Norway and then their cousin Carsten Anker as a civil servant in Copenhagen was handy, strangely enough as the ironworks' previous owner was Carsten's father. Moss Jernverk also had to accept competition, especially from Fritzøe Jernverk, as its monopoly on casting cannons had expired. The first years it was the younger brother, Jess Anker, that presided on the ironworks, with the title "Proprietor of Moss Werk". Jess Anker concluded the construction of the administration building, started by his uncle Erich Ancher.[69]

From 1776 the production of cannons increased under the new owners, and more charcoal than ever before was consumed, up to 10,000 lester annually.[70] In connection with a tenants contract that Jess Anker signed with the family firm in 1781 the net value of Moss Jernverk was estimated to be 177,689 riksdaler.[note 24] The Anker brothers had not divided the inheritance after their father Christian Ancher died in 1767: in reality it was run by Bern Anker and he paid out his brothers in 1783 and bought Moss Jernverk for a total of 80,000 riksdaler to Jess Anker.[71]

Bernt Anker (1784–1805)

Bernt Anker's acquisition of Moss Jernverk (he had effectively controlled the business since his uncle had sold it) marked the end of the work's last glorious period. It also marked a turnaround away from previous ownership considering that the owner did not reside permanently on the premises.[72] The first manager was Lars Semb, a Dane from Thyholm in Jutland. He stayed at Moss Jernverk for the rest of his working days: his notebooks give a good overview of the business. In 1793 there were 278 people living within the ironworks, and besides there were between 150 and 200 in Verlesanden, in the city of Moss, and in Jeløyen who were dependent on the business. In addition to this, all the miners and the farmers produced charcoal.[73]

Among Bernt Anker's large collection of various properties connected to forestry and mining, Moss Jernverk was the one with the largest value.[74]

| Designation in the books | Value i riksdaler |

|---|---|

| The blast furnaces with ore hammer and three houses | 10 000 |

| Macerator for producing the cannons | 250 |

| Drills for the cannons, with forge for sharpening the drills | 4 360 |

| Hammer with storehouse for charcoal | 2 500 |

| The rolling mills | 5 000 |

| Nail factory, with 3 waterpowered hammers and equipment for 10 blacksmiths | 1 800 |

| Hammer and equipment forge | 1 500 |

| Warehouse or «Magazinet» by the fjord, for the ironworks products and storage for grain | 1 200 |

| Main administration house with garden | 8 500 |

| House by the blast furnace | 4 000 |

| Workers houses | 1 750 |

| The mill by the main administration house | 1 500 |

| Upper iron rod hammer | 650 |

| The Kihls mine in Kamboskogen | 300 |

| The Knalstad mines in Vestby | 620 |

| The mines in Drammen | 400 |

| The mines in Skien (13) | 8 575 |

| The mines in and around Arendal (17) | 5 260 |

| The mines in Egersund (8) | 1 100 |

| The Sjødal mine at Nesodden | 140 |

| Countryside properties; Rosnes, Krosser, Skipping, Helgerød and Mosseskogen | 5 820 |

| Iron ore stored at Moss Jernverk | 12 300 |

| Iron ore stored at the mines | 19 000 |

| Cannons in storage | 3 120 |

| Various iron in storage | 5 800 |

| Various goods in warehouse by the fjord | 2 000 |

| Charcoal in storage, around 30 lester | 32 |

| Various manufactured iron goods for sale with Carsten Anker in Copenhagen | 7 400 |

| Coal in storage | 1 635 |

| The Huseby water powered saw | 800 |

| Water powered saw and mill in Moss; the Træschowske (8 850) and Brosagene (1 300) | 10 150 |

| Inventory of timber and cut wood | 15 156 |

| Outstanding debt with charcoal producing farmers | 19 760 |

| Outstanding debt with Oeconomi og Commercekollegiets (the state) | 26 625 |

| Outstanding debt with the admiralty | 2 975 |

| Outstanding debt with the workers | 2 580 |

| Various unsecure debt | 15 280 |

| 110 posts in a total of: | 258 480 |

Against the assets listed above were the debt, a total of 15 creditors with 89,000 riksdaler outstanding, where the largest sum was the permanent loan of 50,000 from the state. In addition Moss Jernverk owned the "holding company" Karen sal. Christian Anchers & Sønner 26,680 riksdaler. In total there were net assets around 170,000 riksdaler in Moss Jernverk at the beginning of 1791.[76]

The firm had according to Bernt Anker lost 150,000 riksdaler on Moss Jernverk when he bought out his brothers and he concluded a reduction in the costs, and in addition a larger capital base, gave various savings.[77] Moss Jernverk did under Bernt Anker's ownership never reach its earlier heights in regards to production volume, innovation and artistic decoration of its products,[78] but economically the first years were very good, as the table below demonstrates.[79]

| Year | Profit | From saws and mills | Transferred to Bernt Anker |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1791 | 14 638 rdl | 4 346 rdl | None |

| 1792 | 15 012 | 6 770 | None |

| 1793 | 24 072 | 14 938 | None |

| 1794 | 14 002 | 8 580 | None |

| 1795 | 14 746 | 9 015 | None |

| 1796 | 15 851 | 7 463 | None |

| 1797 | 23 061 | 10 344 | None |

| 1798 | 19 443 | 9 493 | 6 018 |

| 1799 | 27 430 | 12 243 | 35 107 |

| 1800 | 25 443 | 13 573 | 26 105 |

| 1801 | 28 221 | 15 965 | 30 957 |

| 1802 | 40 690 | 26 453 | 26 410 |

| 1803 | 34 277 | 20 141 | 32 178 |

| 1804 | 33 020 | 18 226 | 40 964 |

| 1805 | 39 981 | 20 635 | None |

The production of iron was still restricted by the availability of charcoal: when the timber trade was good the farmers would rather deliver timber to the saws than use it to produce charcoal and thus ignored the duty to deliver.[note 25] The table above also shows that the income for Moss Jernverk was about equally divided between production of iron and timber. In 1793 the ironworks had to let an order of 22 cannons go to the competitor Fritzøe Verk, owing to lack of charcoal.[80] The main reason for the good economy that the table shows were the turbulent times in Europe,[81] the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), and the fact that the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway managed to stay neutral until 1807.

Later generations have considered the period of Bernt Anker's ownership of Moss Jernverk as the heyday of the ironworks, which can be seen in reviews like this one: "One of the most beautiful works in the country that foreigners admire, is Moss Jernverk."[82] When it came to production of cannons the zenith had clearly been passed: it was never larger under Bernt Anker and no heavy cannons were cast between 1789 and 1797.[83] Most of the output seems to have been iron for barrels, nails and pig iron. No larger improvements or extensions were made: the two blast furnaces that long had been considered fragile had to be used during Anker's lifetime.

The foundation after Bernt Anker (1805–1820)

After Bernt Anker's 1805 death his business empire was organised in a Fideikommiss (a special type of foundation) where the manager at Moss Jernverk, Lars Semb, was one of the three persons on the board. Lars Semb had a quite independent position in the management of the ironworks in the following years.[84] 1805 was a very good year for Moss Jernverk, but in 1807 the situation changed dramatically when the Denmark-Norway Royal Navy launched its attack on Copenhagen and then entered the Napoleonic wars on the French side. During the war Moss Jernverk was vital for the Danish-Norwegian war effort as cannons for warships, fortifications and the army were in great demand. Owing to the loss of warships after Royal Navy's attack new and smaller warships had to be built for the Gunboat War, and a considerable number of them got their guns from Moss Jernverk.[85] With the outbreak of hostilities the problems with lack of charcoal did however disappear, both owing to the lack of timber export and the farmers' patriotic sentiment.

The manager Lars Semb started casting 3-pound and 6-pound cannons during the autumn of 1807 and during the winter the blast furnaces were renovated so that casting of large 24-pound cannons for sjøetaten (shore artillery) could begin in February. There was also a demand for cannons for vessels built for privateers, the privateer vessel Christiania receiving 2 6-pound cannons, 5 12-pound cannons and 4 18-pound carronades. It also cast 18-pound cannons for landetaten (the army), among the fortifications whom acquired those guns was Slevik in Onsøy.[86]

Economically 1808 was a good year for the ironworks, but owing to the heavy production and early start in the winter with casting guns the blast furnaces were heavily worn, the easternmost was used for the last time in 1809. That year delivered a markedly worse result, once again a lack of charcoal, and malnutrition among the workers resulting in many of them becoming ill and dying. The manager Lars Semb reported that one-fourth of the workers died in 1809, among them several of the best craftsmen. Some products had to cease production for quite some time owing to a lack of skilled workers.[87] In 1810 some 50 short 18-pound cannons for brigs were cast, which were the last heavy caliber cannons produced at Moss Jernverk.

Even though the times were hard, it was Moss Jernverk that during these years produced net value with the Bernt Anker fideikommiss, however by the end of the war it was based on the timber from the saw mills. Regarding the ironworks, the blast furnace was not working from April 1812 until July 1814, the production in the forges was with iron from storehouses or from other Norwegian iron works, especially Hakadals verk. Owing to the Continental System and the Royal Navy blockade there were severe problems with food, the local shipowner David Chrystie's brig Refsnes was taken by the British during an attempt to fetch a large cargo of grain in Aalborg.[88]

After the Treaty of Kiel where Denmark had to cede Norway to Sweden, a new situation emerged and the Sjøkrigskommisariatet (admiralty) in Christiania inquired regarding Moss Jernverk capacity for Armour to the country's armed forces. The ironworks was so worn down that it could only produce some ammunition in the crucial year of 1814. Some iron for barrels was also produced and the result for the year was a net profit of 37,000 riksdaler, an amount that could not be compared with the previous years, since the inflation caused by the war was severe.[note 26]

When the war ended in 1814 the situation deteriorated for the ironworks. With the dissolution of Denmark-Norway the monopoly on iron was abandoned and the competition from Swedish and especially English ironworks, that produced in new and less expensive ways, was very hard.[note 27] The times were also bad for the timber trade and in 1817 the profit was no more than 6,000 spesiedaler, the lowest result manager Lars Semb had delivered in the 33 years he had been at Moss Jernverk.[89]

The economy of Bernt Anker's fideikommiss steadily worsened during and after the Napoleonic wars, and on 13 December 1819 manager Lars Semb, together with the other administrators had to sign a petition to the king to appoint a liquidation board for the business. Some parts of Moss Jernverk were sold off on auction, but Bernt Anker's brother Peder Anker, through his in-law Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg bought the major part of it,[note 28] for a total of 30,300 spesiedaler.

Peder Anker (1820–1824)

Moss Jernverk was for some few years still owned by a branch of the Anker family; however, Peder Anker never lived there, but on the magnificent Bogstad gård. The business was run by Andreas Semb, son of the previous manager, in compliance with Anker's in-law count Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg.[90] Anker already owned Bærums Verk and the business in Moss was adjusted to that. In 1824 a new blast furnace was erected; apart from that there were no larger events in the years under Peder Anker. After Anker's death Moss Jernverk was taken over by his daughter Karen and her husband count Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg.

Moss Jernverk in business, culture and politics

Moss Jernverk was indubitably important for the city of Moss and its surroundings, both for the emerging industry and agriculture. Many different tools were produced, some in series, while others were custom-made. The technological expertise that the ironworks had, must have been a huge factor in the business development of the area.[91]

Moss Jernverk was not simply an entity that processed iron ore, it was also a meeting place for the ruling class within business, culture and politics.[note 29] The first royal visit to Moss Jernverk happened most likely one year after the establishment of the ironworks. That was in 1704, when the Danish-Norwegian King Frederick IV visited Moss twice. The main road from the western coast of Sweden through Frederikshald to Christiania, the Frederikshaldske Kongevei went straight through its premises: after 1760 Moss Jernverk is widely encountered in travelers' literature.

The new administration building (the convention house) was ready in 1778 and it was very impressive for its time. Bernt Anker, as Norway's richest person of the time, was a very hospitable owner of Moss Jernverk.[note 30][92] Among the amusements that Bernt Anker provided for his guests were amateur theater plays in a scene that he had built on the ironworks premises. Bernt Anker himself played the main part, as author, instructor and actor.[93]

A quite typical visitor was the South-America count of Miranda: in 1787 he visited and viewed the works, the water falls, the park around the administration building and the cannon foundry. In 1788 the crown prince (later king Frederick VI of Denmark-Norway) and prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel came on a visit. This last visit was just before the campaign against Sweden, later known as "Tyttebærkrigen" (Cowberry War), and the royal entourage got to see casting of cannons, and a cannon test where Bernt Anker himself lit the fuse for the cannon.[94]

Moss Jernverk's central position at this time is seen by how Bernt Anker developed it in new and daring ventures: in the autumn of 1791 the first Norwegian East Indiaman Carl, Prince af Hessen was there to be equipped. The undertaking was surrounded with great interest and the newspaper Norske Intelligenssedler ran news and inspiring poems regarding the voyage. The vessel returned with a large load of pepper, coffee, sugar, arak and other commodities on 30 April 1793.[95]

The hospitality at Moss Jernverk continued after Bernt Anker's death and when Christian August travelled through to Sweden in 1810 (he was elected Swedish crown prince) a large effort was put into giving him a memorable stay.[note 31] The administration building would over the years come to be much used as a royal lodging, in 1816 it was for example used by the crown prince (who later would become king as Charles III John) during a visit to Moss.

Moss Jernverk in 1814

Moss Jernverk played a vital part for the country during the war, 1807–1814. During the summer of 1814 the ironworks and its administration building were in the center of the events. Denmark had ceded Norway to Sweden through the Treaty of Kiel, a Norwegian Constituent Assembly had been held and the Danish stattholder Christian Frederick was declared king of Norway.

On 21 July 1814 the newly elected king established his headquarters at Moss Jernverk in anticipation of an attack from Sweden. The negotiations continued nevertheless, through diplomats from the great powers, whose proclaimed aim was to achieve a peaceful solution. The foreign diplomats arrived at Moss with the final offer from Sweden on 27 July,[96] it was rejected by the Norwegian side the day after and the war with Sweden broke out.[97] The superior Swedish forces advanced rapidly, surrounded Fredrikshald and was ready to advance further into Smaalenene. As the state council was held at the headquarters in Moss on 3 August, the Norwegian position was critically weak.

The cease-fire negotiations started on 10 August and the Swedish generals Magnus Björnstjerna and Anders Fredrik Skjöldebrand arrived at the Norwegian king and government headquarters at Moss Jernverk. They were met by the Norwegian negotiators Jonas Collett; eventually Nils Aall also arrived. The results were presented for the Norwegian government in state council at Moss Jernverk on 13 August.[98] The day after, the decisive and concluding negotiations were completed, where Norway accepted the union with Sweden, the Norwegian constitution was accepted and in a secret clause Christian Frederick agreed to abdicate and leave Norway.[99] Afterwards the results of the negotiations became known as the Convention of Moss.

Christian Frederick stayed a few more days at Moss Jernverk and on 16 August he issued a short but touching proclamation to the Norwegian people, which explained the last month's events, the cease-fire and the convention.[100] The day after, he sailed from Moss to Bygdøy. The Norwegian headquarters stayed for a few more days, but on 31 August the government decided to move its headquarters to Christiania.

For many years the Norwegians viewed the short war, the defeat and the succeeding negotiations in Moss, as a surrender and chose to focus on the events at Eidsvoll in May 1814. This view has, however, changed over time: in 1887 the historian Yngvar Nielsen described the events at Moss as the center of gravity on the Norwegian side in 1814.

"At Eidsvold Jernverk the Norwegians got their personal freedom. At Moss Jernverk Norway got its freedom and Independence as a state.", from the book Moss Jernverk.[101]

Wedel-Jarlsberg (1824–1875)

Moss Jernverk was taken over by count Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg in 1824, but the ownership was first formalized in the years 1826–1829.[102] The situation for the business was severely changed as the Norwegian ironworks lost the last customs protection against Swedish iron. From a principled position, count Wedel voted for abandoning the levies on Swedish iron, even though he, as an owner of several Norwegian ironworks, experienced a huge loss in the establishment of free trade.[103] After he formally had taken over Moss Jernverk, count Wedel noticed that the ironworks still owed 50,000 riksdaler to the state, the standing loan from 1755 that was not paid down. After years of court proceedings, the Supreme Court of Norway ruled that the loan was valid, but not possible to terminate as long as the cannon foundry was kept functional.[104]

In the years 1830–1831, a new large rolling mill was built and before 1834 was built a miniature blast furnace (kupolovn) that over the years partly took the latter's place as it could melt scrap metal. The years around 1830 were still difficult for the ironworks in Norway and Moss Jernverk was no exception, and in the years 1836–1840 the blast furnace was idle for a total of three years.[105]

Count Wedel-Jarlsberg died in 1840, whereupon his son Harald Wedel-Jarlsberg continued the family business, among them Moss Jernverk. It was now run by a manager, from 1836 the German, Ignatius Wankel. The period of hospitality was ended and the royals were no longer lodged in the administration building when they travelled through Moss.[106] Moss Jernverk increasingly became subordinate to Bærums Jernverk, especially after 1840. The market improved in the 1840s, Norwegian iron strangely enough sold well in North-America,[note 32] and improvements were done as in similar foreign ironworks.[note 33]

In the second half of the 1840s the market was very good for Moss Jernverk and the production increased strongly:[note 34] exchange of ore and dividing specialities between the ironworks in Bærum and Moss continued. The production of nails did for example expire in Moss in the 1830s, while the rolling mill was the largest in Norway. By the end of the 1850s the old rolling mill was demolished and a new and much larger one was built, only for the machinery the payment in 1858 was almost 10,999 spesiedaler. This was however the last good period for Norwegian ironworks. After the Crimean War the market became very strained and the Norwegian ironworks were inferior in competition with the Swedish and English works.[107]

In the 1860s the Norwegian ironworks were gradually closed down: the price pressure from cheap steel from the very efficient Bessemer process was too strong.[note 35] Moss Jernverk continued for some years, probably due to the new rolling mill and by the end of the 1860s large amounts of iron were received from Bærum for rolling.[108] A few years after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) a new economical crisis emerged with the Long Depression, which was the final blow for Moss Jernverk. The business was also threatened by the Smaalenene Line, which was decided upon in 1873 and projected right through the ironworks premises. After 1873, the melting of iron ceased. In 1874 and 1875 only the mill and the sawmill were in operation.[note 36] Moss Jernverk was sold for 115,000 spesiedaler (460,000 Norwegian kroner) in 1875 to the local firm M. Peterson & Søn. The premises that the ironworks used were taken over; they were used by the Peterson paper factory until 2012.[109]

Perspective and aftermath

For over 150 years, from the middle of the 17th century and until around 1814, the Norwegian ironworks played a central role in Norway's business,[110][111] in the years before and around 1814 also in politics and culture.[112] Together with timber, fish and shipping, copper and iron was what Norway at that time exported.[note 37][113]

The national importance of the ironworks reached its acme during the Napoleonic Wars, while the years before 1807 were excellent;[note 38] consequently the years afterwards were similarly bad.[note 39] The period after the 1814 dissolution of the union with Denmark was hard for the ironworks,[note 27] shown by a dramatic reduction of production volume.[note 40]

While the ironworks were large scale enterprises within Norway,[note 41] they were small on an international scale. By the end of the 18th century the world's total yearly consumption of iron was around 2/3 million ton – of this the Norwegian ironworks produced some 9,000 ton.[114] In comparison, the Swedish production of iron was around 8 times as large as the Norwegian.[115]

Among the around 16 ironworks in the south-easterly part of Norway[116] Moss Jernverk was one of the medium-sized considering the iron production. In the years 1780-1800 yearly consumption of charcoal by Norwegian ironworks was around 140,000 lester (around 270,000 m³).[note 42] Of the total volume Moss Jernverk used less than 10,000 lester.

During and after the time with ironworks using charcoal it was argued that the charcoal production decimated the woods, but according to the Norwegian geologist Johan Herman Lie Vogt the data does not support this, on the contrary the export of timber in the same period was, for example, 7 times larger.[117] At the same time charcoal was the most expensive ingredient and rising prices of charcoal were the final blow for the Norwegian ironworks.[note 43]

Considering the ironworks as strategically important, the Danish-Norwegian state subsidized them in several different ways,[note 44] partly by giving the ironworks a surrounding area where the farmers were obliged to deliver charcoal (called cirkumferens in Norwegian), and partly by installing heavy custom duties on products from other countries. It also sought to bankroll the ironworks through state purchase of products, such as cannons and munition to the army and the navy.[118] The ironworks had to pay tax, called tithe, in reality it was around 1.5% of the total value of the product.[119] Except from shorter periods in the 17th century when Bærums Jernverk and Eidsvolls Jernverk were owned by a Dutchman and a nobleman from Courland, the enterprises were in Danish-Norwegian possession.[120]

Among its contemporaries Moss Jernverk was especially known for the cannon foundry: it was the first in the country.[121] Among experts of the day the ironworks was held in high esteem: the French metallurgist Gabriel Jars did for example name Moss Jernverk together with Fritzøe Jernverk and Kongsberg Jernverk as the foremost in Norway.[122] In retrospect the ironworks have been acknowledged for their important role in introducing technology and the industrialization of Norway,[note 45] the well-known Norwegian lawyer and economist Anton Martin Schweigaard wrote in 1840, "The mining industry has been a school for mechanical and technical knowledge and insight."[123]

Not much is left from Moss Jernverk: most of the buildings were demolished. Among what is preserved are the administration building (the convention building) and the workers' buildings along the street north of the administration building. The mill by the waterfalls has also been preserved.[124]

Books

- Lauritz Opstad, Moss Jernverk, M. Peterson & søn, Moss, 1950

- Arne Nygård-Nilssen, Norsk jernskulptur, 2 vol., thesis, 1944, Næs jernverksmuseum, 1998 ISBN 978-82-7627-017-4

- J.H.L. Vogt, De gamle norske jernverk, Christiania 1908

- Fritz Hodne, An Economic History of Norway 1815-1970, Tapir 1975, ISBN 82-519-0134-0

- Fritz Hodne og Ola Honningdal Grytten, Norsk økonomi i det 19. århundre, Fagbokforlaget, Bergen, 2000, ISBN 82-7674-352-8

- Oskar Kristiansen, Penge og kapital, næringsveie: Bidrag til Norges økonomiske historie 1815-1830, Cammermeyers boghandels forlag, Oslo 1925

Notes

- ↑ "It was actually over time the supply of charcoal - the woods - that were decisive for development of ironworks. Already from early times there was a decentralization at many works in order to use the woods best and cheapest.", from Fra jernverkenes historie i Norge, p. 57

- ↑ "Master craftsmen and artisans that must be recruited from abroad for building and running the ironworks shall without hindrance be allowed into the country with their people and their belongings, regardless of what nation they belong to. Equally free they shall be allowed to leave after lawful discharge.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 31

- ↑ "The mining and melting enterprises with its mines, blast furnaces, forges and its cirkumferens (area where farmers were imposed supplying charcoal), were as half sovereign enclaves in the pre-industrial Norway, where free farmers were morphed into forced laborers and forced suppliers to the ironworks.", p. 277, Knut Mykland, Norges historie, vol. 7, Cappelens forlag, Oslo 1977

- ↑ "The main reason for the late start of the ironworks, was the lack of charcoal, which would place a heavy burden on it in the future. Charcoal had to be collected for 2-3 years to run the blast furnace for 9-10 months, the oberbergamt (the state authority responsible for mines and smelters) could witness in 1714.", Moss Jernverk, p. 36

- ↑ "Both during the Great Northern War and during the 1760s the protests was aimed at the extra taxes. Protests aimed at other public impositions, as production and supply of coal and transporting various products to the ironworks, are related to the tax protests. The peasantry reacted to all instances of raised duties or reduced prices.", from «Opprør eller legitim politisk praksis?»

- ↑ "There is a very reliable statement that show that the ironworks blast furnace was not in use more than 5,5 years of the 15 years from 1709 to 1723, so the difficulties were huge.", Moss Jernverk, p. 39

- ↑ "The mines in Arendalsfeltet did without doubt play the most important role, as those mines, as we in the following shall describe, delivered around two-thirds of all the iron ore the ironworks consumed.", p. 28, J.H.L. Vogt, De gamle norske jernverk

- ↑ "The ironworks were located besides waterfalls in areas with woods or charcoal, and usually quite far away from the mines, the iron ore transport were for the most ironworks quite cheap, as it mostly were by ships, on small sailing boats or sloops.", p. 28, De gamle norske jernverk

- ↑ "The farmers used unlawful means to win the fight to reduce the burden that enforced delivering of charcoal implied, but we can see that the authorities close to accepted such means as illegal gathering of the peasantry, spreading of information and stop of deliverance's. This was not due to sympathy, but resignation and powerlessness towards the farmers, that had powerful allies in estate owners and timber traders. The disregard for the farmers is easily spotted among the civil servants. At the same time we see that Moss jernverk reacted strongly to the authorities weakness. With other words the farmers illegal means were disputed.", From «Opprør eller legitim politisk praksis?»

- ↑ "This could in no way cover the need, that were estimated to 16,337 lester at full production, broken down as such: For each blast furnace 4,320 lester plus 10% waste, for each of the two rod iron hammers 2,916 lester and for preheating etc 1,000 lester.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 164

- ↑ "The central administration for the army was called Landetaten (in distinction from Sjøetaten). Under its authority were army units, garrisons and fortifications in Denmark-Norway.", from arkivportalen.no

- ↑ "Lars Semb argued in 1797 that the good band iron from Moss was more popular in France, Madeira and the West-Indies than the Swedish.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 185

- ↑ "18 riksdaler and 60 skilling it costed to introduce to Norwegian art history one of its finest names in the 18th century, Henrich Beck. Ancher & Wærn got him here and Moss Jernverk would be his first place to work.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 177

- ↑ "When the ironworks omitted sending its offenders to Kongsberg, a substantial cause was that the ironworks had to pay the costly transport, and even if it was awarded heavy fines there were little use in it, as the sentenced, as a rule, had nothing to pay with.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 189–190

- ↑ "It is told that in 1790 a woman was sent to Copenhagen to be educated as a midwife. She was later on much praised and also worked in the district around the city of Moss. In 1816 she was allowed to move from the ironworks as it could not pay her the wage she deserved.", from «Gamle arbeiderboliger i Østfold» Archived 2007-02-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "The deed of conveyance is dated 26 April 1749.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 78

- ↑ "The direct purchase price was 16,000 riksdaler, but as the stock of iron ore, coal and iron was kept outside the total sum was larger, at least 24,000 riksdaler and possibly as much as 50,000 riksdaler.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 78

- ↑ "Wærn asked for that the enlargement had to include Ås parish with Kroer, Nordby and Frogn, Kråkstad parish with Ski, Skiptvedt, Spydeberg, Enebakk.", Moss Jernverk, p. 94

- ↑ «I shall always be happy to hear of the welfare & prosperity of three Gentlemen in whose conversation I have had so much pleasure, as in that of the two Messrs. Anchor & of their worthy Tutor Mr. Holt. 28th of May 1762 Adam Smith Prof. of Moral Philosophy in the University of Glasgow», from "Adam Smiths norske ankerfeste" Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine (Adam Smits Norwegian anchor pile), article by Preben Munthe in the series Overview of Norwegian monetary history (Tilbakeblikk på norsk pengehistorie) from Norges Bank, 2005

- ↑ "... the ironworks should be managed by Ancher for five years in exchange for him paying Wærn 1,750 riksdaler a year. When this period was over, one of the business partners should buy out the other for 25,000 riksdaler.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 108

- ↑ "On behalf of Mathias he concluded a deal with Erich Ancher that he should take over Moss Jernverk for 14,000 riksdaler. Mathias Wærn waived all right to arrears, outstanding debt, etc, that was before 15 June 1761.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 115

- ↑ "Carsten Anker took part in managing the iron work from 1765–71. The renowned French mining expert Gabriel Jars understood in 1767 the relationship thus as Moss Jernverk is owned by father and son together. At the same time he praised the condition they had got the iron works into, not only by extensions, but also by how the work was organised.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 120

- ↑ "On 2 April 1766 he issues a mortgage bond to Christine Wærns heirs (that is Mathias, Morten and their sisters) on 17,131 riksdaler, that should be paid down with 2,000 riksdaler a year and give a 5% interest, if not the whole bond would be terminated.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 120

- ↑ "... assets were a total of 250,927 riksdaler, while the 18 creditors had 73,238 riksdaler outstanding. Excepting the state loan of 50,000 riksdaler it was fairly small amounts. The net value of the ironworks according to its accounts was thus 177,689 riksdaler.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 132

- ↑ "We have examples of farmers in the 18th century managing to obtain a larger political latitude, and also pressuring the authorities and the elite to significant concessions, such as the charcoal producing farmers by the Oslo fjord managed towards the patron Bernt Anker on Moss Jernverk in the 1780s and the 1790s.", from «Opprør eller legitim politisk praksis?» (Rebellion or legitimate political practice?)

- ↑ "The ironworks books gives many drastic testimonies about the fantastic inflation that culminated in 1814 with prices both on coal and rod iron that was up to 30 times as high as 25 years ago.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 150

- 1 2 "For none of the country's businesses Norway's new political position incurred such a large change as for the production of iron.", from Penge og kapital, næringsveie, side 220

- ↑ "The same day the third call (auction, translator's note) for Moss Jernverk with buildings, stores, etc, plus the farms Nøkkeland and Trolldalen except Påske, Kokke and Berg saw.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 154

- ↑ "The main building was more than the administration center for Moss Jernverk. It came to play a diversified role - not least as a cultural center in the district some years under Bern Anker and even longer as a guest residence for the area.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 201

- ↑ "Moss Jernverk was seen by all foreigners that visited the country. It was due to that the ironworks was owned by the richest man in the country, Bernt Anker, who held court in Moss every autumn.", from Moss bys historie, 1700-1880, p. 132

- ↑ "That the traditions from Bernt Ankers time still was alive in 1810 (the hospitality), Christian August's stay bear witness of. The popular prince from Germany was on his way to Sweden, where he had been selected as heir to the throne. Together with almost all what Eastern Norway had of prominent persons he came on 4 January, 18 from Christiania towards Moss.", fra Moss Jernverk, p. 203–204

- ↑ "In the beginning of the 1840s the Norwegian ironworks strangely enough established a market in the United States, where 'Norway Iron' for a long time was much sought.", from De gamle norske jernverk, p. 60–61

- ↑ "According to the five-year report 1841-45 it consisted of bringing hot air into the blast furnace, and use of the Lancasterian method. The first mentioned improvement had been invoked by Moss Jernverk already within the previous ten years.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 251

- ↑ "The increase in production was thus divided on the various products: pig iron 190%, cast iron 320%, rod iron 350%, rolled iron wholly 500%.", from Moss Jernverk, side 252

- ↑ "There were, as we understand, several factors in play in the closing down of the Norwegian ironworks. But the decisive factor was that in England around 1860 a revolutionary method for converting iron to steel was invented." and "The liquidation went unusually quickly, as before the Bessemer-process took over - both in the 1840s and 1850s - there had been very good times for our ironworks.", from Fra jernverkenes historie i Norge, p. 81-82

- ↑ "In 1874 it is totally silent. The only business the books inform us about is by the farms, mill and sawmill.", from Moss Jernverk, p. 254

- ↑ "Approximate estimates of the value of Norwegian export in 1805 show that timber was the most important with a value of 4,5 million riksdaler. After that was fish with 2,7 million riksdaler, shipping with 2,0 million and iron and copper export with 0,8 million riksdaler.", p. 25-26, Norsk økonomi i det 19. århundre

- ↑ "The ironworks were in those years virtual goldmines for the owners. The production costs were low, but the ironworks had to compete with the timber merchants for the wood.", from Sverre Steen, Det norske folks liv og historie gjennom tidene, 1770–1814, Oslo, 1933 p. 240

- ↑ "The traditional iron export also had hard times after 1815. Norway broke away from Denmark in 1814, at the same time leaving a cozy duty-free area for its iron and glass. Denmark, in turn, imposed heavy import duties on Norwegian iron, at the same time as prices took a downward turn. This was the beginning of the end. As the English coke iron began to compete, the Norwegian iron-foundries, based on charcoal, at the time the most capital-intensive ventures in the country, were forced out, one by one ...", from An Economic History of Norway 1815–1970, p. 23

- ↑ "Also the other ironworks, at this time a total of 12, must in the first years after 1814 in total have reduced their production severely, compared to the situation before the war, as the whole production, as in the period 1791–1807 was a total of 9,000 ton pig iron as a yearly average, in the years 1813–1817 was no more than around 3,500 tons a year.", from Penge og kapital, næringsveie, p. 228

- ↑ "The ironworks, that had roots back to the 1640s, was capital-intensive, export oriented and by Norwegian standards large enterprises.", p. 78, Norsk økonomi i det 19. århundre

- ↑ "On basis of the above compiled statements about the size of production by the end of the 18th century at the four ironworks Fritzøe, Næs, Eidsfos and Hassel - that combined supplied around half of the country's total production of iron - and the use at those ironworks of charcoal, and further on basis of the statements of the total iron production in the country, the total yearly consumption of charcoal by the country's ironworks for this time (1780—1800) be estimated to around 140,000 lester.", from De gamle norske jernverk, p. 41

- ↑ "The charcoal account thus for the old ironworks was more than twice as important, often even three times as important as the iron ore account. And it was, as we shall see later on, the steadily increasing price of charcoal, that in the time around 1860—65 led the ironworks to close permanently.", from De gamle norske jernverk, p. 48, see also p. 62–63

- ↑ "Participation by the state in establishing business was usual until 1814 and the support included money, privileges, import ban, tax exemptions and the right to combustibles within an assigned area (cirkumferens).", p. 79, Norsk økonomi i det 19. århundre

- ↑ "In a development perspective one can see that the mining industry (bergverk in Norwegians, that comprise both mines and ironworks, translators comment) educated skilled workers, that they were a school for technical and administrative competence, and that they stimulated increased purchasing power and the propagation of a money economy.", p. 79 Norsk økonomi i det 19. århundre

References

- ↑ Fra jernverkenes historie i Norge, p. 13

- ↑ Fra jernverkenes historie i Norge, p. 28

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 22

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 20

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 33

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 35

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 41

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 42

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 42-50

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 50

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 55

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 55

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 158–159

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 160–161

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 56

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 57–58

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 162

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 165–166

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 59

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 166–167

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 167

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 61

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 63

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 170

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 168

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 171

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 65

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 66

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 183–184

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 68

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 178–179

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 119

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 172

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 173

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 173

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 174

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 70

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 71

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 72–73

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 188

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 73

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 187

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 189

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 264–265

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 267

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 271

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 75–77

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 78–79

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 80

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 80–81

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 81–83

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 85

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 87

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 91

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 96

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 96–103

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 99

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 105

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 106

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 107

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 107

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 108

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 109–115

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 119

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 119

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 121

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 125

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 129

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 130

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 131

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 132

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 133

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 136

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 133

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 137–138

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 138

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 134

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 142–143

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 139

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 135

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 136

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 142

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 143

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 141, 145

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 146

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 147

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 148

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 149

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 151

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 155

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 185

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 201

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 204–205

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 203

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 208–209

- ↑ P. 432, Knut Mykland, Norges historie, bind 9, Cappelen forlag, 1978

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 212

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 219–225

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 226–234

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 239–240

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p, 243

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 246

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 246

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 245–246

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 250

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 251

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 252-253

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 253

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 255

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 51

- ↑ Fra jernverkenes historie i Norge, p. 54

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 59

- ↑ An Economic History of Norway 1815-1970, p. 17

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 27 og 49

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 55

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 45

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 41–45

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 56

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 56

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 58

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 276

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 277

- ↑ De gamle norske jernverk, p. 54

- ↑ Moss Jernverk, p. 273

External links

- About Moss Jernverk, from Moss by- og industrimuseum (Norwegian)

- About Moss Jernverk, from Lokalhistoriewiki (Norwegian)

- Photo of iron oven manufactured by Moss Jernverk, from digitaltmuseum.no