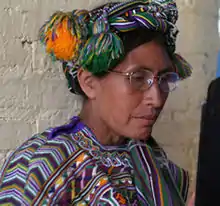

The MicroConsignment Model (MCM) establishes profitable income generating opportunities (and the infrastructure and network for a national, local social enterprise) for primarily women that to date are selling products such as wood-burning stoves, reading glasses, water filters, seeds and gardening techniques and energy efficient lightbulbs to villagers. Through the MCM local individuals with entrepreneurial qualities can start their own business through “sweat equity” and realize profits from inception. Although it rarely works in practice, the model allows for collaboration with local strategic partner organizations to adapt local solutions and train and support local entrepreneurs who serve rural communities within designated territories. What drives the model is an interdisciplinary, intuitive and non-linear approach whereby all stakeholders add value. The model utilizes a rotating capital mechanism with low start-up costs that are continually reinvested. In essence, the MCM strives to intervene at all levels by creating an “ecosystem” whereby problems are diagnosed and products are encountered/designed which are then inserted into the distribution model via the locally trained and supported entrepreneurs.

The MCM is a sustainable, replicable means of delivering health-related and economically beneficial goods and services to remote villages.[1] It uses entrepreneurship to empower the villagers to help themselves. It is a social entrepreneurship approach that is built to organically and opportunistically respond to long-standing challenges.

The MCM creates access to health care-related goods and services in isolated rural communities. The key to the MCM is that local women (AC's) and organizations (SC's) are given the opportunity to become entrepreneurs by selling goods and services in their communities using a consignment mechanism. The MCM creates job opportunities where there weren't any before, and "businesses that can generate jobs for others are the best hope of any country trying to put a serious dent in its poverty rate."[2] Unlike the traditional approach of giving handouts to rural communities, the MCM is scalable, replicable, and sustainable.

The majority of MCM local entrepreneurs are women who have no other opportunities to generate additional household income. Local organizations also work as entrepreneurs primarily through the use of kiosks. The MCM creates synergies between all the stakeholders in the supply chain, from low-cost providers to local organizations, to the local entrepreneurs, and ultimately, to the consumers.

The Problem

Poverty is only a symptom of a real problem of lack of access to services and products. One solution to this problem — providing access to capital for entrepreneurs in the developing world - has been addressed through the microcredit revolution. Other innovations have been developed to address access to education and medical care, including medicines to treat AIDS and TB. However, a model that addresses a wide spectrum of issues, including chronic conditions such as pulmonary and gastrointestinal illnesses, vision problems, malnutrition, water scarcity, lack of energy, and the like, has not been effectively implemented at scale to date. Access can only be created if the product, place, price, and people work in concert to serve those in need in a manner that takes into account their cultural, social, and geographic conditions.[3]

The products necessary for solving problems of access - stoves, water filters, reading glasses, solar panels, and more - already exist. They simply need a way to reach the rural communities that have the greatest need. There is no lack of human capital or local entrepreneurial spirit eager to find solutions. Local transportation networks already reach vulnerable communities, and microcredit organizations are already dedicated to solving the problem of access to needed funds. What has been missing is a model that puts the pieces of the puzzle together.

The Solution

The MCM aims to solve this puzzle by delivering essential products and services at affordable prices to the rural poor in the developing world. MCM entrepreneurs, primarily young women and homemakers who work within defined territories, provide solutions to health problems, save families money, help individuals increase their productivity, and help protect the environment. MCM entrepreneurs offer solutions to help the population at the “base of the pyramid” — in this case, the most vulnerable rural communities — by addressing the “what” (essential products and services), the “who” (rural villagers), and the “where” (rural villages) by creating a highly scalable local distribution network that works to diagnose and address the myriad obstacles confronting these communities in a sustainable way.[4]

History

The MCM was created and developed by Greg Van Kirk (recognized as an Ashoka Fellow in 2008) and George Bucky Glickley. Greg and George were Peace Corps Volunteers in Guatemala from 2001 to 2003.

The MCM first emerged in 2003 when Greg donated money to a wood-burning stove project from the profits of tourism businesses he created in the town of Nebaj, where he was working during the Peace Corps. This donation supplied a handful of stoves to an equal number of families in a local village. Like millions of Guatemalans, these families had always cooked campfire-style on their dirt floors, which had long been recognized as extremely energy inefficient and harmful to the health of family members, particularly women and children. Relief agencies had determined that the construction of inexpensive, locally manufactured, concrete stoves could immediately and dramatically reduce energy costs and improve the health and safety of family members.

Greg realized, however, that merely donating stoves severely limited the capacity for distribution. Once the relief money was expended, nobody else could get a stove. Greg concluded that many more people could obtain these stoves if their distribution was built on a sustainable economy. As a response to this challenge, Greg developed what would become the MCM. Stoves would be locally manufactured, materials provided to local entrepreneurs on consignment and marketed and sold to low income families in villages on an interest-free basis. The money saved in energy costs allowed the stoves to essentially pay for themselves as families made payments over six months. The health, economic and environmental benefits would go on for years. This model would not only provide an essential, high-quality product at an affordable cost to villagers but would provide new income generating opportunities to local individuals as entrepreneurs. Soon after this initial iteration of the model was launched, George joined Greg to further develop and expand this initiative.

Upon finishing their Peace Corps responsibilities, Greg and George stayed in Guatemala and formed New Development Solutions as a means to provide consulting services to USAID, Chemonics, Soros Foundation and the like. In March 2004, they were contracted by Scojo Foundation (now VisionSpring) to work in El Salvador to help them find an effective way to distribute reading glasses to low income villagers. It is estimated that over 90 percent of people over 40 years old will need near-vision reading glasses to see up close. VisionSpring was utilizing a microcredit model at the time to provide local women with a means to distribute the glasses but it wasn't working effectively. Greg and George noted that microcredit is very effective for people who already have established businesses and purchase raw materials from a local distributor to meet unmet demand. However, selling reading glasses, much the same as selling wood-burning stoves, requires a different approach. Due to the fact that awareness needs to be created, a high quality service is the driver, there are no local distributors, training is essential, and the perceived and real financial risk by potential entrepreneurs is very high, they concluded that microcredit was a suboptimal model to achieve VisionSpring's desired outcomes. Microcredit is generally neutral regarding what target businesses buy and sell. Any effort to deliver new, “medium and high intervention” products and services to vulnerable villagers must first look at the villager's needs and then inductively create an entrepreneurial structure that meets those needs.

Greg and George concluded that the MCM could effectively mitigate the challenges that VisionSpring was confronting utilizing microcredit. After in-depth analysis and testing, VisionSpring decided to adopt the MCM as its implementation mechanism. Greg and George realized that the MCM could work as a unique means to get villagers potentially myriad products and services that addressed health, economic, environmental and educational needs. It was this realization that led to them to establish the US non-profit 501 (c) (3) Community Enterprise Solutions in 2004 as the engine to test, develop, implement and expand the MCM in Guatemala and ideally other countries in the future. Their concept was to devise a way to create national scale and local self-sustainability. The key was to train a growing number of primarily women entrepreneurs who could offer a growing mix of essential products and services in an increasing number of remote villages.[5]

The Results

As of September 2009, through the combined efforts of Community Enterprise Solutions and Social Entrepreneur Corps (which offers opportunities for students and recent graduates to volunteer in Guatemala), Soluciones Comunitarias (the social business carrying out the MCM in Guatemala) has trained over 180 local entrepreneurs who have executed approximately 1,800 village campaigns and sold over 35,000 products. The product offering has expanded and now includes wood-burning stoves, reading/near vision glasses, UV protection eyeglasses (January 2005), eye drops (January 2006), water purification buckets (December 2008), vegetable seeds (January 2008), energy efficient light bulbs (January 2008), and solar lamps (January 2010).[6] As well, a new entrepreneurial channel has been created whereby local community organizations are provided with product kiosks and training in order to serve their constituents in new ways and earn extra income in the process.

By some calculations approximately $1,000,000 of direct economic and immeasurable health and environmental impact have been created.[7] In 2008 the MCM reached approximately 375 villages in Guatemala and served 16,200 beneficiaries. This equates to a direct economic impact of $288 per village served and $6.66 per beneficiary.[8]

Gross revenues from the sales of the products total approximately $330,000, and MCM entrepreneurs have earned profits of approximately $60,000. Using the official Guatemalan daily minimum wage of $6.75 - although most people, women in particular, cannot earn anything close to this in rural areas - these earnings equate to approximately 8,888 days of work. There are presently 65 MCM women entrepreneurs and 16 socios comunitarias.[9]

MicroConsignment vs. Microcredit

Microfinance often provides entrepreneurs with much-needed funding that would not otherwise be available. But navigating the terrain of owning a successful business is more complicated than securing loans. The MCM offers "a more focused effort on assisting in entrepreneurship – the whole process from start to end, not just the financing of it."[10]

A key difference between microcredit and the MCM is when the product purchase takes place. In a microcredit model, the entrepreneur first buys the products on credit and then sells them. She then uses her sales revenue to pay back the loan, and ideally buys more products to sell after taking out her profit. If the entrepreneur doesn't sell, she is left with both inventory and debt.

The MCM has the opposite timing. The entrepreneur is first provided products at no cost, then she sells them, pays the supporting organization, and pockets her profits—but only after having completed a sale. At that point she gets her inventory restocked and the cycle begins again. If she doesn't sell, just as in a credit scheme, when the woman doesn't sell, organizational capital is tied up out in the field. However, this capital is tied up in the organization's products that the entrepreneur is simply holding for sale and not in a loan that the entrepreneur must find some way to pay back. The woman can go out and sell the next day, or the next week or next month without falling into debt.

Another difference between the two models can be observed in how entrepreneurs reinvest their earnings. Where credit is used as the enabling mechanism, entrepreneurs may use their earnings for personal consumption before they have time to restock their inventories, which stunts their growth. MCM entrepreneurs reinvest efficiently in their ventures. Because they buy their goods after they make a sale, they do not consider the portion of their revenues that goes to restocking their inventory as theirs.[11]

One of the most compelling differences between microcredit and the MCM is related to risk and uncertainty. Credit works in risky markets, whereas the MCM works in uncertain markets. The power of the MCM lies in the fact that it creates new access and new markets where none previously existed.[12]

As James Surowiecki writes in his article for The New Yorker, “Hanging Tough,” referencing economist Frank Knight, “Risk describes a situation where you have a sense of the range and likelihood of possible outcomes. Uncertainty describes a situation where it’s not even clear what might happen, let alone how likely the possible outcomes are.”[13] However, one person's risk may be another person's uncertainty. Perception, not necessarily reality, defines this distinction. Although there is risk in almost any endeavor, actors in high-risk situations may feel such a level of discomfort that they cross the line from risk into uncertainty.

Credit-driven structures work when the entrepreneur perceives risk. An entrepreneur whose inventory is 100 percent funded up front through credit must sell immediately and sell consistently in order to avoid debt. Therefore, she must understand and feel comfortable with her risk before taking out a loan. For example, if I know my supply-and-demand equation and can predict that I will likely be able to sell my products, I might take out a loan to buy my inventory.

However, when a potential entrepreneur perceives the market as not just risky but uncertain, the MCM has the potential to be an optimal solution. When offering new products to new markets, it can be impossible for an entrepreneur to calculate their risk. If an entrepreneur is highly skeptical of market demand for a new product, she will not want to take out a loan and bear all of the up-front risk.[14]

Consequently, the MCM was designed to fill the gap for previously unknown and/or inaccessible products from the perspective of both entrepreneurs and the villagers — their potential customers. MCM entrepreneurs engage in businesses where supplies have never existed, perceived demand is highly unpredictable, and thus the environment is uncertain. Beneficiaries often barely understand the needs MCM products and services address. For example, MCM entrepreneurs have helped thousands of village weavers who thought they were going blind to solve their problems instantly by getting a free eye exam and buying a $5 pair of reading glasses. The weavers would never have thought of this solution because they did not even understand their problem. The MCM entrepreneurs in turn had never thought they would be able to offer such a service, which was previously only accessible for los ricos, the rich. This is a highly uncertain situation for an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurs must be empowered through a mechanism that finances the support and time necessary to change perceived uncertainty into risk that can be evaluated.[15]

References

- ↑ Micro-Consignment: An Emerging Model of Social Entrepreneurship Archived 2010-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Surowiecki, James. "What Microloans Miss." The New Yorker 17 Mar. 2008.

- ↑ Van Kirk, Greg. "The MicroConsignment Model: Bridging the 'Last Mile' of Access to Products and Services for the Rural Poor." Innovations Hyderabad 2010 (2010): 129.

- ↑ Van Kirk: 129-30.

- ↑ The MicroConsignment Model: The Origins

- ↑ CE Solutions: Impact > Overview

- ↑ "CE Solutions: Impact > Income Generation". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ↑ The MicroConsignment Model: The Origins

- ↑ "CE Solutions: Impact > Income Generation". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ↑ Pryor, Luke. "A New Piece of the Puzzle Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine." The Cornell Daily Sun 17 Nov. 2009.

- ↑ Van Kirk: 131-32.

- ↑ Van Kirk: 132.

- ↑ Surowiecki, James. "Hanging Tough." The New Yorker 20 Apr. 2009.

- ↑ Van Kirk: 133

- ↑ Van Kirk: 134.