Marseille

| |

|---|---|

Prefecture and commune | |

.jpg.webp)  From top to bottom, left to right: Old Port and Notre-Dame de la Garde, narrow streets near Fort Saint-Jean, Sormiou in Calanques National Park, view of the Frioul archipelago from the city, Palais Longchamp, Marseille Cathedral | |

| Motto(s): Actibus immensis urbs fulget massiliensis "The city of Marseille shines from its great achievements" | |

Location of Marseille | |

Marseille  Marseille | |

| Coordinates: 43°17′47″N 5°22′12″E / 43.2964°N 5.37°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur |

| Department | Bouches-du-Rhône |

| Arrondissement | Marseille |

| Canton | 12 cantons |

| Intercommunality | Aix-Marseille-Provence Metropolis |

| Subdivisions | 16 arrondissements |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Benoît Payan[1] (PS) |

| Area 1 | 240.62 km2 (92.90 sq mi) |

| • Urban (2020[2]) | 1,758.2 km2 (678.8 sq mi) |

| • Metro (2020[3]) | 3,971.8 km2 (1,533.5 sq mi) |

| Population | 873,076 |

| • Rank | 2nd in France |

| • Density | 3,600/km2 (9,400/sq mi) |

| • Urban (Jan. 2020[5]) | 1,618,479 |

| • Urban density | 920/km2 (2,400/sq mi) |

| • Metro (Jan. 2020[6]) | 1,879,601 |

| • Metro density | 470/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Marseillais (French) Marselhés (Occitan) Massiliot (ancient) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 13055 /13001-13016 |

| Dialling codes | 0491 or 0496 |

| Website | marseille.fr |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Marseille[lower-alpha 1] (formerly spelled in English as Marseilles; Occitan (Provençal): Marsiho or Marselha) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the Provence region of southern France, it is located on the coast of the Gulf of Lion, part of the Mediterranean Sea, near the mouth of the Rhône river. Its occupants are called Marseillais.

Marseille is the second most populous city in France, with 870,321 inhabitants in 2020 (Jan. census)[7] over a municipal territory of 241 km2 (93 sq mi). Together with its suburbs and exurbs, the Marseille metropolitan area, which extends over 3,972 km2 (1,534 sq mi), had a population of 1,879,601 at the Jan. 2020 census,[6] the third most populated in France after those of Paris and Lyon. The cities of Marseille, Aix-en-Provence, and 90 suburban municipalities have formed since 2016 the Aix-Marseille-Provence Metropolis, an indirectly elected metropolitan authority now in charge of wider metropolitan issues, with a population of 1,903,173 at the Jan. 2020 census.[8]

Founded c. 600 BC by Greek settlers from Phocaea, Marseille is the oldest city in France, as well as one of Europe's oldest continuously inhabited settlements.[9] It was known to the ancient Greeks as Massalia (Greek: Μασσαλία, romanized: Massalía) and to Romans as Massilia.[9][10] The name Massalia probably derives from μᾶζα (mass, lump, barley-cake), the "lump" being the La Garde rock. Marseille has been a trading port since ancient times. In particular, it experienced a considerable commercial boom during the colonial period and especially during the 19th century, becoming a prosperous industrial and trading city. Nowadays the Old Port still lies at the heart of the city, where the manufacture of Marseille soap began some six centuries ago. Overlooking the port is the Basilica of Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde or "Bonne-mère" for the people of Marseille, a Romano-Byzantine church and the symbol of the city. Inherited from this past, the Grand Port Maritime de Marseille (GPMM) and the maritime economy are major poles of regional and national activity and Marseille remains the first French port, the second Mediterranean port and the fifth European port.[11] Since its origins, Marseille's openness to the Mediterranean Sea has made it a cosmopolitan city marked by cultural and economic exchanges with Southern Europe, the Middle East, North Africa and Asia. In Europe, the city has the third largest Jewish community after London and Paris.[12]

In the 1990s, the Euroméditerranée project for economic development and urban renewal was launched. New infrastructure projects and renovations were carried out in the 2000s and 2010s: the tramway, the renovation of the Hôtel-Dieu into a luxury hotel, the expansion of the Velodrome Stadium, the CMA CGM Tower, as well as other quayside museums such as the Museum of Civilisations of Europe and the Mediterranean (MuCEM). As a result, Marseille now has the most museums in France after Paris. The city was named European Capital of Culture in 2013 and European Capital of Sport in 2017. Home of the association football club Olympique de Marseille, one of the most successful and widely supported clubs in France, Marseille has also hosted matches at the 1998 World Cup and Euro 2016. It is also home to several higher education institutions in the region, including the University of Aix-Marseille.

Geography

Marseille is the third-largest metropolitan area in France after Paris and Lyon. To the east, starting in the small fishing village of Callelongue on the outskirts of Marseille and stretching as far as Cassis, are the Calanques, a rugged coastal area interspersed with small fjord-like inlets. Farther east still are the Sainte-Baume (a 1,147 m (3,763 ft) mountain ridge rising from a forest of deciduous trees), the city of Toulon and the French Riviera. To the north of Marseille, beyond the low Garlaban and Etoile mountain ranges, is the 1,011 m (3,317 ft) Mont Sainte Victoire. To the west of Marseille is the former artists' colony of l'Estaque; farther west are the Côte Bleue, the Gulf of Lion and the Camargue region in the Rhône delta. The airport lies to the north west of the city at Marignane on the Étang de Berre.[13]

The city's main thoroughfare (the wide boulevard called the Canebière) stretches eastward from the Old Port to the Réformés quarter. Two large forts flank the entrance to the Old Port—Fort Saint-Nicolas[lower-alpha 2][14] on the south side and Fort Saint-Jean on the north. Farther out in the Bay of Marseille is the Frioul archipelago which comprises four islands, one of which, If, is the location of Château d'If, made famous by the Dumas novel The Count of Monte Cristo. The main commercial centre of the city intersects with the Canebière at Rue St Ferréol and the Centre Bourse (one of the city's main shopping malls). The centre of Marseille has several pedestrianised zones, most notably Rue St Ferréol, Cours Julien near the Music Conservatory, the Cours Honoré-d'Estienne-d'Orves off the Old Port and the area around the Hôtel de Ville. To the south east of central Marseille in the 6th arrondissement are the Prefecture and the monumental fountain of Place Castellane, an important bus and metro interchange. To the south west are the hills of the 7th and 8th arrondissements, dominated by the basilica of Notre-Dame de la Garde. Marseille's main railway station—Gare de Marseille Saint-Charles—is north of the Centre Bourse in the 1st arrondissement; it is linked by the Boulevard d'Athènes to the Canebière.[13]

Climate

The city has a hot-summer mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) with cool-mild winters with moderate rainfall, because of the wet westerly winds, and hot, mostly dry summers.[15] December, January, and February are the coldest months, averaging temperatures of around 12 °C (54 °F) during the day and 4 °C (39 °F) at night. July and August are the hottest months, averaging temperatures of around 28–30 °C (82–86 °F) during the day and 19 °C (66 °F) at night in the Marignane airport (35 km (22 mi) from Marseille) but in the city near the sea the average high temperature is 27 °C (81 °F) in July.[16]

Marseille receives the most sunlight of any French city, 2,897.6 hours per year on average,[17] while the average sunshine in the country is around 1,950 hours. It is also the driest major city with only 532.3 mm (21 in) of precipitation annually, mainly due to the mistral, a cold, dry wind originating in the Rhône Valley that occurs mostly in winter and spring and which generally brings clear skies and sunny weather to the region. Less frequent is the sirocco, a hot, sand-bearing wind, coming from the Sahara. Snowfalls are infrequent; over 50% of years do not experience a single snowfall.

The hottest temperature was 40.6 °C (105.1 °F) on 26 July 1983 during a great heat wave, the lowest temperature was −16.8 °C (1.8 °F) on 13 February 1929 during a strong cold wave.[18]

| Climate data for Marseille-Marignane (Marseille Provence Airport), elevation: 36 m, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1921–present[lower-alpha 3] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

34.9 (94.8) |

39.6 (103.3) |

39.7 (103.5) |

39.2 (102.6) |

34.3 (93.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

39.7 (103.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) |

12.8 (55.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.5 (86.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

20.7 (69.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.9 (76.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

11.7 (53.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.4 (9.7) |

−16.8 (1.8) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−16.8 (1.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.1 (1.85) |

29.8 (1.17) |

29.5 (1.16) |

51.6 (2.03) |

37.7 (1.48) |

27.9 (1.10) |

10.8 (0.43) |

25.8 (1.02) |

82.0 (3.23) |

73.3 (2.89) |

75.9 (2.99) |

40.9 (1.61) |

532.3 (20.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 4.7 | 53.5 |

| Average snowy days | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 147.9 | 173.1 | 234.7 | 250.8 | 298.6 | 337.8 | 372.2 | 333.8 | 263.7 | 196.1 | 150.8 | 138.1 | 2,897.6 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Météo France[21] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[22] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Marseille (Longchamp observatory), elevation: 75 m, 1981–2010 averages, extremes 1868–2003[lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.6 (83.5) |

33.2 (91.8) |

36.9 (98.4) |

40.6 (105.1) |

38.6 (101.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

40.6 (105.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.1 (84.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.9 (40.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.5 (13.1) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51.1 (2.01) |

32.1 (1.26) |

30.7 (1.21) |

51.1 (2.01) |

38.7 (1.52) |

23.5 (0.93) |

7.6 (0.30) |

27.9 (1.10) |

71.6 (2.82) |

78.6 (3.09) |

58.0 (2.28) |

52.3 (2.06) |

523.2 (20.60) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.5 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 52.6 |

| Source 1: Météo France[18] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat.fr[24] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Marseille-Marignane (Marseille Provence Airport), elevation: 36 m, 1961-1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.4 (93.9) |

39.7 (103.5) |

38.6 (101.5) |

32.7 (90.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

39.7 (103.5) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

24.9 (76.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

30.9 (87.6) |

27.4 (81.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

32.4 (90.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.5 (50.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

19.3 (66.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

14.8 (58.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.4 (9.7) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

0.3 (32.5) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 42.4 (1.67) |

47.7 (1.88) |

42.7 (1.68) |

37.0 (1.46) |

38.2 (1.50) |

23.3 (0.92) |

6.0 (0.24) |

25.7 (1.01) |

37.8 (1.49) |

45.0 (1.77) |

48.2 (1.90) |

56.3 (2.22) |

450.3 (17.74) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.5 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 56.8 |

| Average snowy days | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 72 | 67 | 65 | 64 | 63 | 59 | 62 | 69 | 74 | 75 | 77 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 150.0 | 155.5 | 215.1 | 244.8 | 292.5 | 326.2 | 366.4 | 327.4 | 254.3 | 204.5 | 155.5 | 143.3 | 2,835.5 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 53 | 59 | 62 | 65 | 72 | 79 | 77 | 68 | 61 | 54 | 52 | 63 |

| Source 1: NOAA[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity)[19][25] | |||||||||||||

History

Marseille was founded as the Greek colony of Massalia c. 600 BC, and was populated by Greek settlers from Phocaea (modern Foça, Turkey). It became the preeminent Greek polis in the Hellenized region of southern Gaul.[26] The city-state sided with the Roman Republic against Carthage during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), retaining its independence and commercial empire throughout the western Mediterranean even as Rome expanded its empire into Western Europe and North Africa. However, the city lost its independence following the Roman Siege of Massilia in 49 BC, during Caesar's Civil War, in which Massalia sided with the exiled faction at war with Julius Caesar. Afterward, the Gallo-Roman culture was initiated.

The city maintained its position as a premier maritime trading hub even after its capture by the Visigoths in the fifth century AD, although the city went into decline following the sack of AD 739 by the forces of Charles Martel against the Umayyad Arabs. It became part of the County of Provence during the tenth century, although its renewed prosperity was curtailed by the Black Death of the 14th century and a sack of the city by the Crown of Aragon in 1423. The city's fortunes rebounded with the ambitious building projects of René of Anjou, Count of Provence, who strengthened the city's fortifications during the mid-15th century. During the 16th century, the city hosted a naval fleet with the combined forces of the Franco-Ottoman alliance, which threatened the ports and navies of the Genoese Republic.[27]

Marseille lost a significant portion of its population during the Great Plague of Marseille in 1720, but the population had recovered by mid-century. In 1792, the city became a focal point of the French Revolution, and though France's national anthem was born in Strasbourg, it was first sung in Paris by volunteers from Marseille, hence the name the crowd gave it: La Marseillaise. The Industrial Revolution and establishment of the Second French colonial empire during the 19th century allowed for the further expansion of the city, although it was occupied by the German Wehrmacht in November 1942 and subsequently heavily damaged during World War II. The city has since become a major center for immigrant communities from former French colonies in Africa, such as French Algeria.

Economy

Marseille is a major French centre for trade and industry, with excellent transportation infrastructure (roads, sea port and airport). Marseille Provence Airport is the fourth largest in France. In May 2005, the French financial magazine L'Expansion named Marseille the most dynamic of France's large cities, citing figures showing that 7,200 companies had been created in the city since 2000.[28] As of 2019, the Marseille metropolitan area had a GDP amounting to US$81.4 billion,[lower-alpha 5] or US$43,430 per capita (purchasing power parity).[29]

Port

Historically, the economy of Marseille was dominated by its role as a port of the French Empire, linking the North African colonies of Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia with Metropolitan France. The Old Port was replaced as the main port for trade by the Port de la Joliette (now part of Marseille-Fos Port) during the Second Empire and now contains restaurants, offices, bars and hotels and functions mostly as a private marina. The majority of the port and docks, which experienced decline in the 1970s after the oil crisis, have been recently redeveloped with funds from the European Union. Fishing remains important in Marseille and the food economy of Marseille is fed by the local catch; a daily fish market is still held on the Quai des Belges of the Old Port.

The economy of Marseille and its region is still linked to its commercial port, the first French port and the fifth European port by cargo tonnage, which lies north of the Old Port and eastern in Fos-sur-Mer. Some 45,000 jobs are linked to the port activities and it represents €4 billion of added value to the regional economy.[30] 100 million tons of freight pass annually through the port, 60% of which is petroleum, making it number one in France and the Mediterranean and number three in Europe. However, in the early 2000s, the growth in container traffic was being stifled by the constant strikes and social upheaval.[31] The port is among the 20th firsts in Europe for container traffic with 1,062,408 TEU and new infrastructure has already raised the capacity to 2 million TEU.[32] Marseille is connected with the Rhône via a canal and thus has access to the extensive waterway network of France. Petroleum is shipped northward to the Paris basin by pipeline. The city also serves as France's leading centre of oil refining.

Companies, services and high technologies

In recent years, the city has also experienced a large growth in service sector employment and a switch from light manufacturing to a cultural, high-tech economy. The Marseille region is home to thousands of companies, 90% of which are small and medium enterprises with less than 500 employees.[33] Among the most famous ones are CMA CGM, container-shipping giant; Compagnie maritime d'expertises (Comex), world leader in sub-sea engineering and hydraulic systems; Airbus Helicopters, an Airbus division; Azur Promotel, an active real estate development company; La Provence, the local daily newspaper; RTM, Marseille's public transport company; and Société Nationale Maritime Corse Méditerranée (SNCM), a major operator in passenger, vehicle and freight transportation in the Western Mediterranean. The urban operation Euroméditerranée has developed a large offer of offices and thus Marseille hosts one of the main business district in France.

Marseille is the home of three main technopoles: Château-Gombert (technological innovations), Luminy (biotechnology) and La Belle de Mai (17,000 sq.m. of offices dedicated to multimedia activities).[34][35]

Tourism and attractions

The port is also an important arrival base for millions of people each year, with 2.4 million including 890,100 from cruise ships.[30] With its beaches, history, architecture and culture (24 museums and 42 theatres), Marseille is one of the most visited cities in France, with 4.1 million visitors in 2012.[36]

They take place in three main sites, the Palais du Pharo, Palais des Congrès et des Expositions (Parc Chanot) and World Trade Center.[37] In 2012 Marseille hosted the World Water Forum. Several urban projects have been developed to make Marseille attractive. Thus new parks, museums, public spaces and real estate projects aim to improve the city's quality of life (Parc du 26e Centenaire, Old Port of Marseille,[38] numerous places in Euroméditerranée) to attract firms and people. Marseille municipality acts to develop Marseille as a regional nexus for entertainment in the south of France with high concentration of museums, cinemas, theatres, clubs, bars, restaurants, fashion shops, hotels, and art galleries.

Employment

Unemployment in the economy fell from 20% in 1995 to 14% in 2004.[39] However, Marseille unemployment rate remains higher than the national average. In some parts of Marseille, youth unemployment is reported to be as high as 40%.[40]

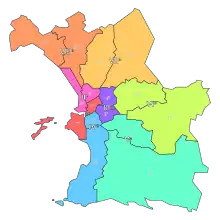

Administration

The city of Marseille is divided into 16 municipal arrondissements, which are themselves informally divided into 111 neighbourhoods (French: quartiers). The arrondissements are regrouped in pairs, into 8 sectors, each with a mayor and council (like the arrondissements in Paris and Lyon).[41] Municipal elections are held every six years and are carried out by sector. There are 303 councilmembers in total, two-thirds sitting in the sector councils and one third in the city council.

The 9th arrondissement of Marseille is the largest in terms of area because it comprises parts of Calanques National Park. With a population of 89,316 (2007), the 13th arrondissement of Marseille is the most populous one.

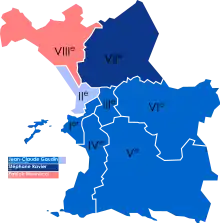

From 1950 to the mid-1990s, Marseille was a Socialist (PS) and Communist (PCF) stronghold. Gaston Defferre (PS) was consecutively reelected six times as Mayor of Marseille from 1953 until his death in 1986. He was succeeded by Robert Vigouroux of the European Democratic and Social Rally (RDSE). Jean-Claude Gaudin of the conservative UMP was elected Mayor of Marseille in 1995. Gaudin was reelected in 2001, 2008 and 2014.

In recent years, the Communist Party has lost most of its strength in the northern boroughs of the city, whereas the National Front has received significant support. At the last municipal election in 2014, Marseille was divided between the northern arrondissements dominated by the left (PS) and far-right (FN) and the southern part of town dominated by the conservative (UMP). Marseille is also divided in twelve cantons, each of them sending two members to the Departmental Council of the Bouches-du-Rhône department.

Mayors of Marseille since the beginning of the 20th century

.jpg.webp)

| Mayor | Term start | Term end | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siméon Flaissières | 1895 | 1902 | POF | |

| Albin Curet (acting) | 1902 | 1902 | Independent | |

| Jean-Baptiste-Amable Chanot | 1902 | 1908 | FR | |

| Emmanuel Allard | 1908 | 1910 | FR | |

| Clément Lévy (acting) | 1910 | 1910 | Independent | |

| Bernard Cadenat | 1910 | 1912 | SFIO | |

| Jean-Baptiste-Amable Chanot | 1912 | 1914 | FR | |

| Eugène Pierre | 1914 | 1919 | Independent | |

| Siméon Flaissières | 1919 | 1931 | SFIO | |

| Simon Sabiani | 1931 | 1931 | Independent | |

| Georges Ribot | 1931 | 1935 | RAD | |

| Henri Tasso | 1935 | 1939 | SFIO | |

| Nominated administrators | 1939 | 1946 | Independent | |

| Jean Cristofol | 1946 | 1947 | PCF | |

| Michel Carlini | 1947 | 1953 | RPF | |

| Gaston Defferre | 1953 | 1986 | SFIO, PS | |

| Jean-Victor Cordonnier (acting) | 1986 | 1986 | PS | |

| Robert Vigouroux | 1986 | 1995 | PS, DVG | |

| Jean-Claude Gaudin | 1995 | 2020 | UDF-PR, DL, UMP, LR | |

| Michèle Rubirola | 2020 | 2020 | EELV | |

| Benoît Payan | 2020 | Incumbent | PS |

Demographics

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Immigration

| Largest groups of immigrants[lower-alpha 6] and natives of Overseas France in the Marseille metropolitan area | |

| Country/territory of birth | Population (2019)[46][47] |

|---|---|

| 59,927 | |

| 17,340 | |

| 16,704 | |

| 11,740 | |

| 10,457 | |

| 7,708 | |

| 7,384 | |

| 6,863 | |

| 4,514 | |

| | 3,841 |

| 3,173 | |

| 2,885 | |

| 2,754 | |

| 2,594 | |

| 2,444 | |

| | 2,304 |

| | 2,168 |

| 2,078 | |

| 1,767 | |

| 1,732 | |

| 1,614 | |

Because of its pre-eminence as a Mediterranean port, Marseille has always been one of the main gateways into France. This has attracted many immigrants and made Marseille a cosmopolitan melting pot. By the end of the 18th century about half the population originated from elsewhere in Provence mostly and also from southern France.[48][49]

Economic conditions and political unrest in Europe and the rest of the world brought several other waves of immigrants during the 20th century: Greeks and Italians started arriving at the end of the 19th century and in the first half of the 20th century, up to 40% of the city's population was of Italian origin;[50] Russians in 1917; Armenians in 1915 and 1923; Vietnamese in the 1920s, 1954 and after 1975;[51] Corsicans during the 1920s and 1930s; Spanish after 1936; Maghrebis (both Arab and Berber) in the inter-war period; Sub-Saharan Africans after 1945; Maghrebi Jews in the 1950s and 1960s; the Pieds-Noirs from the former French Algeria in 1962; and then from Comoros.

At the 2019 census, 81.4% of the inhabitants of the Marseille metropolitan area were natives of Metropolitan France, 0.6% were born in Overseas France, and 18.0% were born in foreign countries (two-fifth of whom French citizens from birth, in particular Pieds-Noirs from Algeria arrived in Metropolitan France after the independence of Algeria in 1962).[46] A quarter of the immigrants living in the Marseille metropolitan area were born in Europe (half of them in Italy, Portugal, and Spain), 46% were born in the Maghreb (almost two-third of them in Algeria), 14% in the rest of Africa (almost half of them in the Indian Ocean islands of Comoros, Madagascar, and Mauritius, not counting those born in Réunion and Mayotte who are not legally immigrants), and 15.0% in the rest of the world (not counting those born in the French overseas departments of the Americas and in the French territories of the South Pacific, who are not legally immigrants).[47]

In 2002, about one third of the population of Marseille can trace their roots back to Italy.[52] Marseille also has the second-largest Corsican and Armenian populations of France. Other significant communities include Maghrebis, Turks, Comorians, Chinese, and Vietnamese.[53]

The largest immigrant communities (including descendants) in 2002 were Italians (290,000 Italians, or 33%), then Muslims - mainly Maghrebis (200,000 Muslims, or 23%), then Corsicans (100,000 Corsicans, or 11.5%), then Armenians (80,000 Armenians, or 9%).[52]

In 1999, in several arrondissements, about 40% of the young people under 18 were of Maghrebi origin (at least one immigrant parent).[54]

Since 2013 a significant number of Central- and Eastern European immigrants have settled in Marseille, attracted by better job opportunities and the good climate of this Mediterranean city. The main nationalities of the immigrants are Romanian and Polish.[55]

| Born in Metropolitan France | Born in Overseas France | Born in foreign countries with French citizenship at birth[a] | Immigrants[b] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81.4% | 0.6% | 7.1% | 10.9% | |||||

| from Europe | from the Maghreb[c] | from Africa (excl. Maghreb) | ||||||

| 2.7% | 5.0% | 1.5% | ||||||

| from Turkey | from Asia (excl. Turkey) | from the Americas & Oceania | ||||||

| 0.4% | 1.0% | 0.3% | ||||||

| ^a Persons born abroad of French parents, such as Pieds-Noirs and children of French expatriates. ^b An immigrant is by French definition a person born in a foreign country and who did not have French citizenship at birth. Note that an immigrant may have acquired French citizenship since moving to France, but is still listed as an immigrant in French statistics. On the other hand, persons born in France with foreign citizenship (the children of immigrants) are not listed as immigrants. ^c Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria | ||||||||

| Source: INSEE[46][47] | ||||||||

| Year | Born in Metropolitan France | Born in Overseas France | Born in foreign countries with French citizenship at birth[a] | Immigrants[b] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 75.9% | 0.8% | 8.2% | 15.1% | |||||||||||||||

| from Europe | from the Maghreb[c] | from Africa (excl. Maghreb) | |||||||||||||||||

| 2.6% | 7.5% | 2.7% | |||||||||||||||||

| from Turkey | from Asia (excl. Turkey) | from the Americas & Oceania | |||||||||||||||||

| 0.6% | 1.4% | 0.3% | |||||||||||||||||

| 1999 | 78.9% | 0.9% | 8.8% | 11.4% | |||||||||||||||

| from EU-15 | non-EU-15 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2.1% | 9.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| ^a Persons born abroad of French parents, such as Pieds-Noirs and children of French expatriates. ^b An immigrant is by French definition a person born in a foreign country and who did not have French citizenship at birth. Note that an immigrant may have acquired French citizenship since moving to France, but is still listed as an immigrant in French statistics. On the other hand, persons born in France with foreign citizenship (the children of immigrants) are not listed as immigrants. ^c Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria | |||||||||||||||||||

| Source: INSEE[46][56] | |||||||||||||||||||

Religion

According to data from 2010, major religious communities in Marseille include:

- Christians - 909,930 or 84.5% (Roman Catholic 68.5%, [57] Armenian Apostolic 7.5%, Protestant [mostly Pentecostal] 7.1%, Eastern Orthodox 1.4%)

- Muslim - 200,000 or 25% [58][59]

- Non-religious -156.000 or 14.5%

- Jewish - 52,000 - 80,000[58] or 4.9%

- Hindu - 4,000 or 0.4%

- Buddhist - 3,000 or 0.3%.[60]

Culture

Marseille is a city that has its own unique culture and is proud of its differences from the rest of France.[61] Today it is a regional centre for culture and entertainment with an important opera house, historical and maritime museums, five art galleries and numerous cinemas, clubs, bars and restaurants.

Marseille has a large number of theatres, including La Criée, Le Gymnase and the Théâtre Toursky. There is also an extensive arts centre in La Friche, a former match factory behind the Saint-Charles station. The Alcazar, until the 1960s a well known music hall and variety theatre, has recently been completely remodelled behind its original façade and now houses the central municipal library.[62] Other music venues in Marseille include Le Silo (also a theatre) and GRIM.

Marseille has also been important in the arts. It has been the birthplace and home of many French writers and poets, including Victor Gélu, Valère Bernard, Pierre Bertas,[63] Edmond Rostand and André Roussin. The small port of l'Estaque on the far end of the Bay of Marseille became a favourite haunt for artists, including Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne (who frequently visited from his home in Aix), Georges Braque and Raoul Dufy.

Multi-cultural influences

Rich and poor neighborhoods exist side by side. Although the city is not without crime, Marseille has a larger degree of multicultural tolerance. Urban geographers[64] say the city's geography, being surrounded by mountains, helps explain why Marseille does not have the same problems as Paris. In Paris, ethnic areas are segregated and concentrated in the periphery of the city. Residents of Marseille are of diverse origins, yet appear to share a similar particular identity.[65][66] An example is how Marseille responded in 2005, when ethnic populations living in other French cities' suburbs rioted, but Marseille remained relatively calm.[67]

Marseille served as the European Capital of Culture for 2013 along with Košice.[68] It was chosen to give a 'human face' to the European Union to celebrate cultural diversity and to increase understanding between Europeans.[69] One of the intentions of highlighting culture is to help reposition Marseille internationally, stimulate the economy, and help to build better interconnection between groups.[70] Marseille-Provence 2013 (MP2013) featured more than 900 cultural events held throughout Marseille and the surrounding communities. These cultural events generated more than 11 million visits.[71] The European Capital of Culture was also the occasion to unveil more than 600 million euros in new cultural infrastructure in Marseille and its environs, including the MuCEM designed by Rudy Ricciotti.

Early on, immigrants came to Marseille locally from the surrounding Provence region. By the 1890s immigrants came from other regions of France as well as Italy.[72] Marseille became one of Europe's busiest ports by 1900.[66] Marseille has served as a major port where immigrants from around the Mediterranean arrive.[72] Marseille continued to be multicultural. Armenians from the Ottoman Empire began arriving in 1913. In the 1930s, Italians settled in Marseille. After World War II, a wave of Jewish immigrants from North Africa arrived. In 1962, a number of French colonies gained their independence, and the French citizens from Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia arrived in Marseille.[73] The city had an economic downturn and lost many jobs. Those who could afford to move left and the poorest remained. For a while, the mafia appeared to run the city, and for a period of time the communist party was prominent.[73]

Multi-cultural Marseille can be observed by a visitor at the market at Noailles, also called Marché des Capucins, in old town near the Old Port. There, Lebanese bakeries, an African spice market, Chinese and Vietnamese groceries, fresh vegetables and fruit, shops selling couscous, shops selling Caribbean food are side by side with stalls selling shoes and clothing from around the Mediterranean. Nearby, people sell fresh fish and men from Tunisia drink tea.[73]

Although most Armenians arrived after the Armenian Genocide, Armenians had a long presence even before the 20th and late 19th centuries. Armenians, having an extensive trade network worldwide, massively traded with Marseille and its port. Most notably, during the 16th century, and after the Armenians gained a monopoly over Iranian silk, which was granted to them by Shah Abbas of Iran, the trade flow of Armenians of Marseille increased tremendously. Merchants of Armenian origin received trade privileges in France by Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu (1585–1642) and later on Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683) Marseille a free port in 1669. One notable Armenian-Iranian merchant gained a patent from Louis XIV (1638–1715) over Iranian silk.[74] Armenians also became successful money-lenders and bankers in the city. Due to these policies and the multiculturalism of the city of Marseille, Armenians became very wealthy, and the legacy of the Armenians in the city still lives on.

Tarot de Marseille

The most commonly used tarot deck takes its name from the city; it has been called the Tarot de Marseille since the 1930s—a name coined for commercial use by the French cardmaker and cartomancer Paul Marteau, owner of B–P Grimaud. Previously this deck was called Tarot italien (Italian Tarot) and even earlier it was simply called Tarot. Before being de Marseille, it was used to play the local variant of tarocchi before it became used in cartomancy at the end of the 18th century, following the trend set by Antoine Court de Gébelin. The name Tarot de Marseille (Marteau used the name ancien Tarot de Marseille) was used by contrast to other types of Tarots such as Tarot de Besançon; those names were simply associated with cities where there were many cardmakers in the 18th century (previously several cities in France were involved in cardmaking).[75]

Another local tradition is the making of santons, small hand-crafted figurines for the traditional Provençal Christmas creche. Since 1803, starting on the last Sunday of November, there has been a Santon Fair in Marseille; it is currently held in the Cours d'Estienne d'Orves, a large square off the Vieux-Port.

Opera

Marseille's main cultural attraction was, since its creation at the end of the 18th century and until the late 1970s, the Opéra. Located near the Old Port and the Canebière, at the very heart of the city, its architectural style was comparable to the classical trend found in other opera houses built at the same time in Lyon and Bordeaux. In 1919, a fire almost completely destroyed the house, leaving only the stone colonnade and peristyle from the original façade.[76][77] The classical façade was restored and the opera house reconstructed in a predominantly Art Deco style, as the result of a major competition. Currently the Opéra de Marseille stages six or seven operas each year.[78]

Since 1972, the Ballet national de Marseille has performed at the opera house; its director from its foundation to 1998 was Roland Petit.

Popular events and festivals

There are several popular festivals in different neighborhoods, with concerts, animations, and outdoor bars, like the Fête du Panier in June. On 21 June, there are dozens of free concerts in the city as part of France's Fête de la Musique, featuring music from all over the world. Being free events, many Marseille residents attend.

Marseille hosts a Gay Pride event in early July. In 2013, Marseille hosted Europride, an international LGBT event, 10 July–20.[79] At the beginning of July, there is the International Documentary Festival.[80] At the end of September, the electronic music festival Marsatac takes place. In October, the Fiesta des Suds offers many concerts of world music.[81]

Hip hop music

Marseille is also well known in France for its hip hop music.[82] Bands like IAM originated from Marseille. Other known groups include Fonky Family, Psy 4 de la Rime (including rappers Soprano and Alonzo), and Keny Arkana. In a slightly different way, ragga music is represented by Massilia Sound System.

Food

- Bouillabaisse is the most famous seafood dish of Marseille. It is a fish stew containing at least three varieties of very fresh local fish: typically red rascasse (Scorpaena scrofa); sea robin (fr: grondin); and European conger (fr: congre).[83] It can include gilt-head bream (fr: dorade); turbot; monkfish (fr: lotte or baudroie); mullet; or silver hake (fr: merlan), and it usually includes shellfish and other seafood such as sea urchins (fr: oursins), mussels (fr: moules); velvet crabs (fr: étrilles); spider crab (fr: araignées de mer), plus potatoes and vegetables. In the traditional version, the fish is served on a platter separate from the broth.[84] The broth is served with rouille, a mayonnaise made with egg yolk, olive oil, red bell pepper, saffron, and garlic, spread on pieces of toasted bread, or croûtons.[85][86] In Marseille, bouillabaisse is rarely made for fewer than ten people.[87]

- Aïoli is a sauce made from raw garlic, lemon juice, eggs and olive oil, served with boiled fish, hard boiled eggs and cooked vegetables.[85]

- Anchoïade is a paste made from anchovies, garlic, and olive oil, spread on bread or served with raw vegetables.[85]

- Bourride is a soup made with white fish (monkfish, European sea bass, whiting, etc.) and aïoli.[88]

- Fougasse is a flat Provençal bread, similar to the Italian focaccia. It is traditionally baked in a wood oven and sometimes filled with olives, cheese or anchovies.

- Navette de Marseille are, in the words of food writer M. F. K. Fisher, "little boat-shaped cookies, tough dough tasting vaguely of orange peel, smelling better than they are."[89]

- Farinata#French variations is chickpea flour boiled into a thick mush, allowed to firm up, then cut into blocks and fried.[90]

- Pastis is an alcoholic beverage made with aniseed and spice. It is extremely popular in the region.[91]

- Pieds paquets is a dish prepared from sheep's feet and offal.[88]

- Pistou is a combination of crushed fresh basil and garlic with olive oil, similar to the Italian pesto. The "soupe au pistou" combines pistou in a broth with pasta and vegetables.[85]

- Tapenade is a paste made from chopped olives, capers, and olive oil (sometimes anchovies may be added).[92]

Films set in Marseille

Marseille has been the setting for many films.

Main sights

Marseille is listed as a major centre of art and history. The city has many museums and galleries and there are many ancient buildings and churches of historical interest.

Central Marseille

_(14181557102).jpg.webp)

Most of the attractions of Marseille (including shopping areas) are located in the 1st, 2nd, 6th and 7th arrondissements. These include:[93][94]

- The Old Port or Vieux-Port, the main harbour and marina of the city. It is guarded by two massive forts (Fort Saint-Nicolas and Fort Saint-Jean) and is one of the main places to eat in the city. Dozens of cafés line the waterfront. The Quai des Belges at the end of the harbour is the site of the daily fish market. Much of the northern quayside area was rebuilt by the architect Fernand Pouillon after its destruction by the Nazis in 1943.

- The Hôtel de Ville (City Hall), a baroque building dating from the 17th century.

- The Centre Bourse and the adjacent Rue St Ferreol district (including Rue de Rome and Rue Paradis), the main shopping area in central Marseille.

- The Porte d'Aix, a triumphal arch commemorating French victories in the Spanish Expedition.

- The Hôtel-Dieu, a former hospital in Le Panier, transformed into an InterContinental hotel in 2013.

- La Vieille Charité in Le Panier, an architecturally significant building designed by the Puget brothers. The central baroque chapel is situated in a courtyard lined with arcaded galleries. Originally built as an alms house, it is now home to an archeological museum and a gallery of African and Asian art, as well as bookshops and a café. It also houses the Marseille International Poetry Centre.[95]

- The Cathedral of Sainte-Marie-Majeure or La Major, founded in the fourth century, enlarged in the 11th century and completely rebuilt in the second half of the 19th century by the architects Léon Vaudoyer and Henri-Jacques Espérandieu. The present day cathedral is a gigantic edifice in Romano-Byzantine style. A romanesque transept, choir and altar survive from the older medieval cathedral, spared from complete destruction only as a result of public protests at the time.

- The 12th-century parish church of Saint-Laurent and adjoining 17th-century chapel of Sainte-Catherine, on the quayside near the cathedral.

- The Abbey of Saint-Victor, one of the oldest places of Christian worship in Europe. Its fifth-century crypt and catacombs occupy the site of a Hellenic burial ground, later used for Christian martyrs and venerated ever since. Continuing a medieval tradition,[96] every year at Candlemas a Black Madonna from the crypt is carried in procession along Rue Sainte for a blessing from the archbishop, followed by a mass and the distribution of "navettes" and green votive candles.

Museums

In addition to the two in the Centre de la Vieille Charité, described above, the main museums are:[97]

- The Musée des Civilisations de l'Europe et de la Méditerranée (MuCEM) and the Villa Méditerranée were inaugurated in 2013. The MuCEM is devoted to the history and culture of European and Mediterranean civilisations. The adjacent Villa Méditerranée, an international centre for cultural and artistic interchange, is partially constructed underwater. The site is linked by footbridges to the Fort Saint-Jean and to the Panier.[98][99]

- The Musée Regards de Provence, opened in 2013, is located between the Cathedral of Notre Dame de la Majeur and the Fort Saint-Jean. It occupies a converted port building constructed in 1945 to monitor and control potential sea-borne health hazards, in particular epidemics. It now houses a permanent collection of historical artworks from Provence as well as temporary exhibitions.[100]

- The Musée du Vieux Marseille, housed in the 16th-century Maison Diamantée, describing everyday life in Marseille from the 18th century onwards.

- The Musée des Docks Romains preserves in situ the remains of Roman commercial warehouses, and has a small collection of objects, dating from the Greek period to the Middle Ages, that were uncovered on the site or retrieved from shipwrecks.

- The Marseille History Museum (Musée d'Histoire de Marseille), devoted to the history of the town, located in the Centre Bourse. It contains remains of the Greek, and Roman history of Marseille as well as the best preserved hull of a sixth-century boat in the world. Ancient remains from the Hellenic port are displayed in the adjacent archeological gardens, the Jardin des Vestiges.

- The Musée Cantini, a museum of modern art near the Palais de Justice. It houses artworks associated with Marseille as well as several works by Picasso.

- The Musée Grobet-Labadié, opposite the Palais Longchamp, houses an exceptional collection of European objets d'art and old musical instruments.

- The 19th-century Palais Longchamp, designed by Esperandieu, is located in the Parc Longchamp. Built on a grand scale, this italianate colonnaded building rises up behind a vast monumental fountain with cascading waterfalls. The jeux d'eau marks and masks the entry point of the Canal de Provence into Marseille. Its two wings house the Musée des beaux-arts de Marseille (a fine arts museum), and the Natural History Museum (Muséum d'histoire naturelle de Marseille).

- The Château Borély is located in the Parc Borély, a park off the Bay of Marseille with the Jardin botanique E.M. Heckel, a botanical garden. The Museum of the Decorative Arts, Fashion and Ceramics opened in the renovated château in June 2013.[101]

- The Musée d'Art Contemporain de Marseille (MAC), a museum of contemporary art, opened in 1994. It is devoted to American and European art from the 1960s to the present day.[102]

- The Musée du Terroir Marseillais in Château-Gombert, devoted to Provençal crafts and traditions.[103]

The MuCEM, Musée Regards de Provence and Villa Mediterannée, with Notre Dame de la Majeur on the right

The MuCEM, Musée Regards de Provence and Villa Mediterannée, with Notre Dame de la Majeur on the right.jpg.webp) The sixteenth century Maison Diamantée which houses the Musée du Vieux Marseille

The sixteenth century Maison Diamantée which houses the Musée du Vieux Marseille The music room in the Grobet-Labadié museum

The music room in the Grobet-Labadié museum The Palais Longchamp with its monumental fountain

The Palais Longchamp with its monumental fountain

Outside central Marseille

The main attractions outside the city centre include:[94]

- The 19th-century Basilica of Notre-Dame de la Garde, an enormous Romano-Byzantine basilica built by architect Espérandieu in the hills to the south of the Old Port. The terrace offers views of Marseille and its surroundings.[104]

- The Stade Vélodrome, the home stadium of the city's main football team, Olympique de Marseille.

- The Unité d'Habitation, an influential and iconic modernist building designed by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier in 1952. On the third floor is the gastronomic restaurant, Le Ventre de l'Architecte. On the roof is the contemporary gallery MaMo opened in 2013.

- The Docks de Marseille, a 19th-century warehouse transformed into offices.[105]

- The Pharo Gardens, a park with views of the Mediterranean and the Old Port.[106]

- The Corniche, a waterfront road between the Old Port and the Bay of Marseille.[106]

- The beaches at the Prado, Pointe Rouge, Les Goudes, Callelongue and Le Prophète.[107]

- The Calanques, a mountainous coastal area, is home to Calanques National Park which became France's tenth national park in 2012.[108][109]

- The islands of the Frioul archipelago in the Bay of Marseille, accessible by ferry from the Old Port. The prison of Château d'If was one of the settings for The Count of Monte Cristo, the novel by Alexandre Dumas.[110] The neighbouring islands of Ratonneau and Pomègues are joined by a human-made breakwater. The site of a former garrison and quarantine hospital, these islands are also of interest for their marine wildlife.

Education

A number of the faculties of the three universities that comprise Aix-Marseille University are located in Marseille:

- University of Provence

- Université de la Méditerranée Aix-Marseille II

- Université Paul Cézanne Aix-Marseille III

In addition Marseille has four grandes écoles:

- Ecole Centrale de Marseille part of Centrale Graduate School

- École pour l'informatique et les nouvelles technologies

- Institut polytechnique des sciences avancées

- KEDGE Business School

The main French research bodies including the CNRS, INSERM and INRA are all well represented in Marseille. Scientific research is concentrated at several sites across the city, including Luminy, where there are institutes in developmental biology (the IBDML), immunology (CIML), marine sciences and neurobiology (INMED), at the CNRS Joseph Aiguier campus (a world-renowned institute of molecular and environmental microbiology) and at the Timone hospital site (known for work in medical microbiology). Marseille is also home to the headquarters of the IRD, which promotes research into questions affecting developing countries.

Transport

International and regional transport

The city is served by an international airport, Marseille Provence Airport, located in Marignane. The airport is the fifth busiest French airport, was known as the fourth most important European traffic growth in 2012.[111] An extensive network of motorways connects Marseille to the north and west (A7), Aix-en-Provence in the north (A51), Toulon (A50) and the French Riviera (A8) to the east.

Gare de Marseille Saint-Charles is Marseille's main railway station. It operates direct regional services to Aix-en-Provence, Briançon, Toulon, Avignon, Nice, Montpellier, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Nantes, etc. Gare Saint-Charles is also one of the main terminal stations for the TGV in the south of France making Marseille reachable in three hours from Paris (a distance of over 750 km) and just over one and a half hours from Lyon. There are also direct TGV lines to Lille, Brussels, Nantes, Geneva, Strasbourg and Frankfurt as well as Eurostar services to London (just in the summer) and Thello services to Milan (just one a day), via Nice and Genoa.

There is a new long-distance bus station adjacent to new modern extension to the Gare Saint-Charles with destinations mostly to other Bouches-du-Rhône towns, including buses to Aix-en-Provence, Cassis, La Ciotat and Aubagne. The city is also served with 11 other regional trains stations in the east and the north of the city, including Marseille-Blancarde.

Marseille has a large ferry terminal, the Gare Maritime, with services to Corsica, Sardinia, Algeria and Tunisia.

Public transport

Marseille is connected by the Marseille Métro train system operated by the Régie des transports de Marseille (RTM). It consists of two lines: Line 1 (blue) between Castellane and La Rose opened in 1977 and Line 2 (red) between Sainte-Marguerite-Dromel and Bougainville opened between 1984 and 1987. An extension of the Line 1 from Castellane to La Timone was completed in 1992, another extension from La Timone to La Fourragère (2.5 km (1.6 mi) and 4 new stations) was opened in May 2010. The Métro system operates on a turnstile system, with tickets purchased at the nearby adjacent automated booths. Both lines of the Métro intersect at Gare Saint-Charles and Castellane. Three bus rapid transit lines are under construction to better connect the Métro to farther places (Castellane -> Luminy; Capitaine Gèze – La Cabucelle -> Vallon des Tuves; La Rose -> Château Gombert – Saint Jérôme).

An extensive bus network serves the city and suburbs of Marseille, with 104 lines and 633 buses. The three lines of the tramway,[112] opened in 2007, go from the CMA CGM Tower towards Les Caillols.

As in many other French cities, a bike-sharing service nicknamed "Le vélo", free for trips of less than half an hour, was introduced by the city council in 2007.[113]

A free ferry service operates between the two opposite quays of the Old Port. From 2011 ferry shuttle services operate between the Old Port and Pointe Rouge; in spring 2013 it will also run to l'Estaque.[114] There are also ferry services and boat trips available from the Old Port to Frioul, the Calanques and Cassis.

Sport

.jpg.webp)

The city boasts a wide variety of sports facilities and teams. The most popular team is the city's football club, Olympique de Marseille, which was the finalist of the UEFA Champions League in 1991, before winning the competition in 1993, the only French club to do so as of 2023. The club also became finalists of the UEFA Europa League in 1999, 2004 and 2018. The club had a history of success under then-owner Bernard Tapie. The club's home, the Stade Vélodrome, which can seat around 67,000 people, also functions for other local sports, as well as the national rugby team. Stade Velodrome hosted a number of games during the 1998 FIFA World Cup, 2007 Rugby World Cup, UEFA Euro 2016 and 2023 Rugby World Cup. The local rugby teams are Marseille XIII and Marseille Vitrolles Rugby.

Marseille is famous for its important pétanque activity, it is even renowned as the pétanque capitale.[115] In 2012 Marseille hosted the Pétanque World Championship and the city hosts every year the Mondial la Marseillaise de pétanque, the main pétanque competition.

Sailing is a major sport in Marseille. The wind conditions allow regattas in the warm waters of the Mediterranean. Throughout most seasons of the year it can be windy while the sea remains smooth enough to allow sailing. Marseille has been the host of 8 (2010) Match Race France events which are part of the World Match Racing Tour. The event draws the world's best sailing teams to Marseille. The identical supplied boats (J Boats J-80 racing yachts) are raced two at a time in an on the water dogfight which tests the sailors and skippers to the limits of their physical abilities. Points accrued count towards the World Match Racing Tour and a place in the final event, with the overall winner taking the title ISAF World Match Racing Tour Champion. Match racing is an ideal sport for spectators in Marseille, as racing in close proximity to the shore provides excellent views. The city was also considered as a possible venue for 2007 America's Cup.[116]

CN Marseille has traditionally been one of France's dominant Water polo teams as it won the Championnat de France a total of 36 times.

Marseille is also a place for other water sports such as windsurfing and powerboating. Marseille has three golf courses. The city has dozens of gyms and several public swimming pools. Running is also popular in many of Marseille's parks such as Le Pharo and Le Jardin Pierre Puget. An annual footrace is held between the city and neighbouring Cassis: the Marseille-Cassis Classique Internationale.

Notable people

Marseille was the birthplace of:

- Pytheas (fl. fourth century BC), Greek merchant, geographer and explorer

- Petronius (fl. first century AD), Roman novelist and satirist

- Pierre Demours (1702–1795), physician

- Pierre Blancard (1741-1826), introduced the chrysanthemum to France

- Jean-Henri Gourgaud, aka. "Dugazon" (1746–1809), actor

- Jean-Baptiste Benoît Eyriès (1767–1846), geographer, author and translator

- Désirée Clary (1777–1860), wife of King Carl XIV Johan of Sweden, and therefore Queen Desirée or Queen Desideria of Sweden

- Sabin Berthelot (1794–1880), naturalist and ethnologist

- Adolphe Thiers (1797–1877), first president of the Third Republic

- Étienne Joseph Louis Garnier-Pages (1801–1841), politician

- Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), caricaturist and painter

- Joseph Autran (1813–1877), poet

- Charles-Joseph-Eugene de Mazenod (1782–1861), bishop of Marseille and founder of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate.

- Lucien Petipa (1815–1898), ballet dancer

- Joseph Mascarel (1816–1899), mayor of Los Angeles

- Marius Petipa (1818–1910), ballet dancer and choreographer

- Ernest Reyer (1823–1909), opera composer and music critic

- Olivier Émile Ollivier (1825–1913), statesman

- Victor Maurel (1848–1923), operatic baritone

- Joseph Pujol, aka. "Le Pétomane" (1857–1945), entertainer

- Charles Fabry (1867–1945), physicist

- Edmond Rostand (1868–1918), poet and dramatist

- Pavlos Melas (1870–1904), Greek army officer

- Louis Nattero, (1870–1915), painter

- Vincent Scotto (1876–1952), guitarist, songwriter[117]

- Charles Camoin (1879–1965), fauvist painter

- Henri Fabre (1882–1984), aviator and inventor of the first seaplane

- Frédéric Mariotti (1883–1971), actor

- Darius Milhaud (1892–1974), composer and teacher[118][119]

- Berty Albrecht (1893–1943), French Resistance, Croix de Guerre

- Antonin Artaud (1897–1948), author

- Henri Tomasi (1901–1971), composer and conductor

- Zino Francescatti (1902–1991), violinist

- Fernandel (1903–1971), actor

- Marie-Madeleine Fourcade (1909–1989), French Resistance, Commander of the Légion d'honneur

- Éliane Browne-Bartroli (Eliane Plewman, 1917–1944), French Resistance, Croix de Guerre

- César Baldaccini (1921–1998), sculptor

- Louis Jourdan (1921–2015), actor

- Jean-Pierre Rampal (1922–2000), flautist

- Alice Colonieu, (1924–2010), ceramist

- Paul Mauriat (1925–2006), orchestra leader, composer

- Maurice Béjart (1927–2007), ballet choreographer

- Régine Crespin (1927–2007), opera singer

- Ginette Garcin (1928–2010), actor

- André di Fusco (1932–2001), known as André Pascal, songwriter, composer

- Henry de Lumley (born 1934), archaeologist

- Sacha Sosno (1937–2013), sculptor

- Michel Lazdunski (born 1938), biochemist

- Jean-Pierre Ricard (born 1944), cardinal, archbishop of Bordeaux

- Georges Chappe (born 1944), cyclist

- Jean-Claude Izzo (1945–2000), author

- Denis Ranque (born 1952), businessman

- Ariane Ascaride (born 1954), actress

- Myriam Fox-Jerusalmi (born 1961), world champion slalom canoer

- Eric Cantona (born 1966), Manchester United and France national team football player

- Christophe Galtier (born 1966), football manager and former player

- Patrick Fiori (born 1969), singer

- Marc Panther (born 1970), member of the popular Japanese rock band Globe

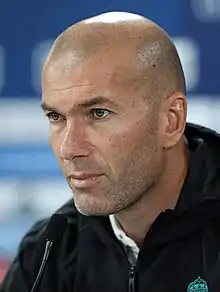

- Zinedine Zidane (born 1972), football player and former captain of the France national football team

- Romain Barnier (born 1976), freestyle swimmer

- Sébastien Grosjean (born 1978), tennis player

- Philippe Echaroux (born 1983), photographer

- Mathieu Flamini (born 1984), football player

- Rémy Di Gregorio (born 1985), cyclist

- Jessica Fox (born 1994), French-born Australian slalom canoer[120]

- Lucas Hernandez (born 1996), football player

- Théo Hernandez (born 1997), football player

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Marseille is twinned with 14 cities, all of them being port cities, with the exception of Marrakech.[121]

Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1958)

Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1958).svg.png.webp) Antwerp, Belgium (1958)

Antwerp, Belgium (1958) Copenhagen, Denmark (1958)

Copenhagen, Denmark (1958) Dakar, Senegal (1968)

Dakar, Senegal (1968) Genoa, Italy (1958)

Genoa, Italy (1958) Glasgow, Scotland (2006)

Glasgow, Scotland (2006) Haifa, Israel (1958)

Haifa, Israel (1958) Hamburg, Germany (1958)

Hamburg, Germany (1958) Kobe, Japan (1961)

Kobe, Japan (1961) Marrakech, Morocco (2004)

Marrakech, Morocco (2004) Odesa, Ukraine (1972)

Odesa, Ukraine (1972) Piraeus, Greece (1984)

Piraeus, Greece (1984) Shanghai, China (1987)

Shanghai, China (1987) Tunis, Tunisia (1989)

Tunis, Tunisia (1989)

Partner cities

In addition, Marseille has signed various types of formal agreements of cooperation with 27 cities all over the world:[122]

Agadir, Morocco (2003)[122]

Agadir, Morocco (2003)[122] Alexandria, Egypt (1990)[122]

Alexandria, Egypt (1990)[122] Algiers, Algeria (1980)[122]

Algiers, Algeria (1980)[122] Bamako, Mali (1991)[122]

Bamako, Mali (1991)[122] Barcelona, Spain (1998)[122]

Barcelona, Spain (1998)[122] Beirut, Lebanon (2003)[122]

Beirut, Lebanon (2003)[122] Casablanca, Morocco (1998)[122]

Casablanca, Morocco (1998)[122] Gdańsk, Poland (1992)[122][123]

Gdańsk, Poland (1992)[122][123] Istanbul, Turkey (2003)[122]

Istanbul, Turkey (2003)[122] Jerusalem (2006)[122]

Jerusalem (2006)[122] Limassol, Cyprus[124]

Limassol, Cyprus[124] Lomé, Togo (1995)[122]

Lomé, Togo (1995)[122] Lyon, France

Lyon, France Meknes, Morocco (1998)[122]

Meknes, Morocco (1998)[122] Montevideo, Uruguay (1999)[122]

Montevideo, Uruguay (1999)[122] Nice, France

Nice, France Nîmes, France

Nîmes, France Rabat, Morocco (1989)[122]

Rabat, Morocco (1989)[122] Saint Petersburg, Russia (2013)[122]

Saint Petersburg, Russia (2013)[122] Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina (2003)[122]

Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina (2003)[122] Thessaloniki, Greece[125]

Thessaloniki, Greece[125] Tirana, Albania (1991)[122][126]

Tirana, Albania (1991)[122][126] Tripoli, Libya (1991)[122]

Tripoli, Libya (1991)[122] Tunis, Tunisia (1998)[122]

Tunis, Tunisia (1998)[122] Valparaíso, Chile (2013)[122]

Valparaíso, Chile (2013)[122] Varna, Bulgaria (2007)[122]

Varna, Bulgaria (2007)[122] Yerevan, Armenia (1992)[122][127][128]

Yerevan, Armenia (1992)[122][127][128]

See also

Notes

- ↑ /mɑːrˈseɪ/ mar-SAY, French: [maʁsɛj] ⓘ, locally [maχˈsɛjə] ⓘ; Occitan: Marsiho in mistralian norm or Occitan: Marselha in classical norm [maʀˈsejɔ, -ˈsijɔ]; Italian: Marsiglia.

- ↑ Port Saint-Nicholas is a 17th-century fortress built around the small medieval chapel of Entrecasteaux near the Abbey of St Victor, Marseille.

- ↑ The altitude provided from the site varies about 31 m, a much larger value than the margin of error, which may mean that the station was relocated ms in one of the data had maintained the elevation from when measured, which should be used.[19][20]

- ↑ Although the values have a record of more than two decades, it can not be used as an overview of the local climate, as it does not reach the minimum period of 30 years required by WMO.[23]

- ↑ Constant PPP US dollars, base year 2015.

- ↑ An immigrant is a person born in a foreign country not having French citizenship at birth. Note that an immigrant may have acquired French citizenship since moving to France, but is still considered an immigrant in French statistics. On the other hand, persons born in France with foreign citizenship (the children of immigrants) are not listed as immigrants.

- ↑ Not including Hong Kong and Macau

References

- ↑ "Répertoire national des élus: les maires" (in French). data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises. 13 September 2022.

- ↑ "Comparateur de territoire - Unité urbaine 2020 de Marseille-Aix-en-Provence (00759)". INSEE. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ↑ "Comparateur de territoire - Aire d'attraction des villes 2020 de Marseille - Aix-en-Provence (003)". INSEE. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ↑ "Populations légales 2021". The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 28 December 2023.

- ↑ INSEE. "Statistiques locales - Marseille - Aix-en-Provence : Unité urbaine 2020 - Population municipale 2020". Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 INSEE. "Statistiques locales – Marseille – Aix-en-Provence : Aire d'attraction des villes 2020 – Population municipale 2020". Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- 1 2 INSEE. "Historique des populations communales - Recensements de la population 1876-2020" (in French). Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ↑ "Statistiques locales - Métropole d'Aix-Marseille-Provence : Intercommunalité 2021 - Population municipale 2020". INSEE. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- 1 2 Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, page needed A.

- ↑ Ebel, Charles (1976). Transalpine Gaul: the emergence of a Roman province. Brill Archive. pp. 5–16. ISBN 90-04-04384-5., Chapter 2, Massilia and Rome before 390 B.C.

- ↑ Notteboom, Theo (11 March 2009). "Les ports maritimes et leur arrière-pays intermodal". Concurrence entre les ports et les liaisons terrestres avec l'arrière-pays. Tables rondes FIT. pp. 27–81. doi:10.1787/9789282102299-3-fr. ISBN 9789282102268. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ Mandel, Maud S. (5 January 2014). Muslims and Jews in France. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400848584. ISBN 978-1-4008-4858-4.

- 1 2 Michelin Guide to Provence, ISBN 2-06-137503-0

- ↑ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, p. 384

- ↑ "Marseille, France Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ Météo France, 1981–2010 averages

- ↑ Deluzarche, Céline. "France : top 20 des villes les plus ensoleillées". Futura Sciences (in French). Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- 1 2 "Marseille–Obs (13)" (PDF). Fiche Climatologique: Statistiques 1981–2010 et records (in French). Meteo France. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Normales et records pour la période 1981-2010 à Marseille Observatoire Longchamp" (in French). Infoclimat. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Marseille-Marignane (07650) - WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved 4 February 2019. Archived 8 February 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Marignane (13)" (PDF). Fiche Climatologique: Statistiques 1991–2020 et records (in French). Meteo France. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ↑ "Marseille, France - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ↑ The Definition of the Standard WMO Climate Normal: The Key to Deriving Alternative Climate Normals, American Meteorological Society (June 2011). Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ "Normales et records pour la période 1981-2010 à Marseille Observatoire Longchamp" (in French). Infoclimat. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ "07650: Marseille / Marignane (France)". ogimet.com. OGIMET. 29 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ Patrick Boucheron, et al., eds. France in the World: A New Global History (2019) pp 30-35.

- ↑ "France-Ottoman | Ottoman History". ottoman.ahya.net. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ↑ Neumann, Benjamin (1 May 2005). "Les villes qui font bouger la France" [Cities That Are Moving France]. L'Express (in French). Paris: Roularta Media Group. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- ↑ OECD. "City statistics : Economy". Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- 1 2 "Record Container Year as Marseilles Fos Sets Vision for Future" (PDF). Port of Marseille-Fos. 5 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ "Les ports français" (PDF). Cour de comptes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- ↑ "Marseille: Strategic Call for Arkas". Port Strategy. 11 April 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Marseille Metropole Provence" (in French). Marseille-provence.com. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ "Technopôles". Marseille Provence Metropole. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Marseilles Euroméditerranée: Between Europe and the Mediterranean" (PDF). Euroméditerranée. Établissement Public d'Aménagement Euroméditerranée. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2003.

- ↑ "Découvrir Marseille – Une ville de tourisme" (in French). Marseille.fr. 26 September 2004. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "Economie – Tourisme d'affaires et congrès" (in French). Marseille.fr. 26 September 2004. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ Ravenscroft, Tom (5 March 2013). "Foster Unveils Reflective Events Pavilion in Marseille". Architects Journal. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Jean-Claude Gaudin: Sénateur-Maire de Marseille" (in French). Polytechnique.fr. 2 March 2004. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael (19 December 2007). "In Marseille, Rap Helps Keep the Peace". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ↑ "Mairies d'Arrondissements" (in French). Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- 1 2 Dupâquier, Jacques, ed. (1989). Histoire de la population française. Vol. 4: De 1914 à nos jours. Quadrige / Presses Universitaires de France. p. 35. ISBN 978-2-1304-6824-0.

- ↑ Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Marseille, EHESS (in French).

- ↑ EHESS. "Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui". Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ↑ INSEE. "Statistiques locales - Marseille - Aix-en-Provence : Aire d'attraction des villes 2020 - Population municipale (historique depuis 1876)". Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Individus localisés au canton-ou-ville en 2019 - Recensement de la population - Fichiers détail" (in French). Institut national de la statistique et des études économiqes (INSEE). Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Étrangers - Immigrés en 2019 : Aire d'attraction des villes 2020 de Marseille - Aix-en-Provence (003) : IMG1B - Pays de naissance détaillé - Sexe : Ensemble" (in French). Institut national de la statistique et des études économiqes (INSEE). Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ↑ Liauzu 1996

- ↑ Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, page needed E.

- ↑ "Local0631EN:Quality0667EN" (PDF). Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ↑ Guillemin, Alain. "Les Vietnamiens a Marseille" (in French). Archived from the original on 23 March 2014.

- 1 2 "Citizenship and integration: Marseille, model of integration?". 28 September 2004. Archived from the original on 28 September 2004. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ↑ "Diverse Marseille Spared in French Riots". NPR. 10 December 2005. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ Michèle Tribalat (2007). "Les concentrations ethniques en France" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2011.

- ↑ "Insee – Population – Les immigrés récemment arrivés en France – Une immigration de plus en plus européenne". insee.fr.

- ↑ "IMG1B - Population immigrée par sexe, âge et pays de naissance en 2019 - Commune de Marseille (13055)" (in French). Institut national de la statistique et des études économiqes (INSEE). Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ↑ "Archdiocese of Marseille". Catholic hierarchy. 1 January 2020.

- 1 2 Katz, Ethan (2015). The Burdens of Brotherhood: Jews and Muslims from North Africa to France. Harvard University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780674088689.

Today, 80,000 Jews and 200,000 Muslims, many sharing North African heritage, live in Marseille.

- ↑ B. Murphy, Alexander (2008). The European Culture Area: A Systematic Geography. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 9780742579064.

The French port city of Marseille alone has 200,000 Muslims in its population of 1,400,000, as well as some 50 mosque.

- ↑ "Marseille Espérance. All different, all Marseilles, Part II". France Diplomatie. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ Chris Kimble. "Marseille Culture". Marseillecityofculture.eu. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ History of library

- ↑ "Pierre Bertas".

- ↑ Ingram, Mark (2009). "Euro-Mediterranean Marseille: Redefining State Cultural Policy in an Era of Transnational Governance". City & Society. Vol. 21. pp. 268–292.

- ↑ Moreau, Alain (2001). Migrations, identités, et territoires à Marseille.Migrations, identités, et territoires à Marseille. Paris: Hamattan. pp. 27–52.

- 1 2 Dickey, Christopher (March 2012). "Marseille's Melting Pot". National Geographic Magazine. Vol. 2012, no. 3.

- ↑ Williams, D (27 October 2005). "Long Integrated, Marseille Is Spared. Southern Port Was Largely Quiet as Riots Raged in Other French Cities". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Marseille Provence 2013: European Capital of Culture". Archived from the original on 26 August 2010.

- ↑ Bullen, Claire (2010). "European Capitals of Culture and Everyday Cultural Diversity: A Comparison of Liverpool (UK) and Marseilles (France)". European Cultural Foundation.

- ↑ Zukin, S (1995). The Culture of Cities. Oxford: Blackwell.

- ↑ "11 millions de visiteurs pour la capitale européenne de la culture". Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- 1 2 Clark, Peter (2009). European Cities and Towns. Oxford, England: Oxford. pp. 283, 247.

- 1 2 3 Kimmelman, Michael (4 October 2013). "Marseille, the Secret Capital of France". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Armenian trade networks".

- ↑ see: Musée du Vieux-Marseille (2004), Cartes à jouer & tarots de Marseille: La donation Camoin, Alors Hors Du Temps, ISBN 2-9517932-7-8, official catalogue of the permanent collection of playing cards from the museum of Vieux-Marseille, including a detailed history of Tarot de Marseille Depaulis, Thierry (1984), Tarot, jeu et magie, Bibliothèque nationale, ISBN 2-7177-1699-8

- ↑ "Opera in Genoa, Nice, Marseille, Montpellier, Barcelona". Capsuropera.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ↑ "Schmap Marseille Sights & Attractions – 6th arrond". Schmap.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ↑ "Actualités". Opéra de Marseille (in French).

- ↑ "Marseille 2013". EuroPride. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ "March 2013 Newsletter". FIDMarseille. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "octobre, 2012 – Dock des Suds : festivals, concerts de musique et location de salles à Marseille" (in French). Dock des Suds. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "In Marseille, Rap Helps Keep the Peace", Article in New York Times, December 2007 Cannon, Steve; Dauncey, Hugh (2003), Popular music in France from chanson to techno: culture, identity, and society, Ashgate Publishing, pp. 194–198, ISBN 0-7546-0849-2

- ↑ "La bouillabaisse classique doit comporter les 'trois poissons': rascasse, grondin, congre." Michelin Guide Vert -Côte dAzur, 1990, page 31

- ↑ |History and traditional recipe of bouillabaisse on the site of the Marseille Tourism Office

- 1 2 3 4 David, Elizabeth (1999). French Provincial Cooking. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-118153-2.

- ↑ Wright, Clifford (2002). Real Stew. Harvard Common Press. ISBN 1-55832-199-3.