Mabel Ping-Hua Lee | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

李彬华 | |||||||||||

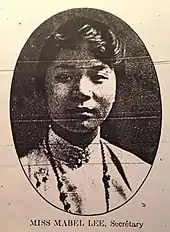

.jpg.webp) Lee c. 1923–1925 | |||||||||||

| Born | October 7, 1896 | ||||||||||

| Died | 1966 (aged 69–70) New York City, U.S. | ||||||||||

| Education | Barnard College (BA; MEd) Columbia University (PhD) | ||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 李彬华[1] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee[2] (Chinese: 李彬华; October 7, 1896 – 1966) was a Chinese-American women's rights activist and minister who campaigned for women's suffrage in the United States. Later in life, Lee became a Baptist minister, working with the First Chinese Baptist Church in Chinatown.[3][4]

Born in China and raised in New York City, Lee received a bachelor's degree and master's degree from Barnard College of Columbia University, and later a doctorate in economics from Columbia University in 1921, becoming the first Chinese woman in the United States to earn a doctorate in economics.[5] In the 1910s, Lee became an activist for women's suffrage, and participated in the 1912 New York City women's suffrage parade, where she rode on horseback. Following the eventual passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, Lee still was unable to vote due to her status as a Chinese immigrant per the Chinese Exclusion Act. She would not gain the right to vote until at least the passage of the Magnuson Act in 1943.[3][6][7]

Lee became a Baptist minister in 1924, after taking over her father's church following his death. She went on to run the First Chinese Baptist Church for forty years, while also becoming a leader within the American Baptist Home Mission Society. Lee additionally became a community advocate for the Chinese community in New York and residents of Chinatown, working with the Chinese Community Center. In recognition of her life and advocacy on behalf of women and Chinese immigrants in the United States, the Chinatown U.S. Post Office on Doyers Street was renamed in her honor in 2017.

Early life

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was born on October 7, 1896[8] in Guangzhou during the Qing dynasty of China.[9][10][6] Her father was Lee To or Lee Towe, a minister who emigrated to the United States and worked in the American Baptist Home Mission Society.[11] He first served as a missionary to the Chinese community in Washington state in 1898 and then was appointed to minister at the Morning Star Mission in New York City, where he became a leading member in New York's Chinatown.[12][13] Her mother's name is recorded in US census documents alternately as Lennick or Libreck Lee.[14]

Lee spent her early childhood in China, attending a missionary school where she learned English. She was raised by her mother and grandmother while her father was in America.[15] It has been reported she traveled with her mother to America in the summer of 1900 when she was four years old to reunite with her father.[13] However, most articles, including a 1912 New-York Tribune article, made mention that she settled with her family in New York by 1905. She was also an only child but the same New-York Tribune article writes of a baby sister.[12][11] Her family lived in a tenement at 53 Bayard Street in Chinatown. She attended New York City's public schools, specifically Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn, which was a school meant to accommodate the increase in immigrant children.[14][12][16]

Education

In 1913, Lee began attending Barnard College where she majored in history and philosophy.[12] She joined the Debating Club and Chinese Students' Association. In 1916, she ran for president of this student association against Tse-ven Soong, who later became finance minister of China's national government. She wrote articles for The Chinese Students’ Monthly, in which she championed for woman's suffrage and argued for equality as necessary in a democracy. While at Barnard College, she also received a master's degree in educational administration.[13][12][10]

In 1917, Lee was admitted to Columbia University for a doctorate in economics. The Chinese government was impressed with her research in the agricultural economy and granted her a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship which allowed her to continue her studies. She became the first woman to win this scholarship. She was the vice president of the Columbia Chinese Club and became associate editor of The Chinese Students’ Monthly. Lee graduated in 1921 or 1922 and earned a PhD in economics from Columbia University in 1921.[17][12][13] She was selected by the Board of Council of Columbia University as the University Scholar in Economics for her research work in agricultural economics. This was the first time a Chinese student was given this award. Her final dissertation was titled "The Economic History of China: With Special Reference to Agriculture" and was later published.[14][16] Her thesis was the first agricultural economics text written by a foreign Chinese student and maintained a balanced view of western economic ideology and Chinese traditional economic thought within the context of modern agricultural reform.[13]

Post-education

After her studies, Lee traveled to Europe in 1923 to study postwar economics. A local Baptist newspaper reported, "On March 28, 1923, Miss Lee sailed for France where she is now engaged in the study of European Economics, in fuller preparation for her life work, in her native land, China. A position of great trust and signal honor awaits her arrival in China."[12] Lee had numerous job opportunities including an offer from a Chinese firm interested in trade from the United States to China.[15] She was also recruited for the Dean of Women students at the University of Amoy, now Xiamen University.[12] However, after the sudden death of her father, she went back to New York City in 1924 to care for her mother. She was appointed by the American Baptist Home Mission Society to take on her father's duties and became chairman of the Morning Star Mission. Lee continued to travel to her homeland, eager to join the new generation of workers and help the people of China, but on her third trip to China in 1937, she decided otherwise. Racial and sexist discrimination were likely to reduce her chances of attaining her goals and it became unsafe to live in China with the Japanese invasion and the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War. These factors coupled with her familial and religious duties ultimately helped her decide to stay in New York.[12][14][18][15]

Women's suffrage

Mabel Lee's early suffragist and nationalist consciousness was influenced by her father's religious and nationalistic views for China and by New York's liberal environment.[13][15] Before she was writing essays advocating equality in The Chinese Students’ Monthly, she was riding horseback as a teenager in the campaign for women's suffrage in New York state. On May 4, 1912, a fifteen year old Lee led a parade in support of women's voting rights with the likes of Annie Rensselaer Tinker, the Women's Political Union, and Anna Howard Shaw in New York. The parade grew a large crowd, up to ten thousand people were in attendance. Shaw carried a National American Woman Suffrage Association banner that stated: "N.A.W.S.A Catching Up with China" while Lee rode on horseback.[11][19][20][6] She also led Chinese and Chinese-American women in a parade down Fifth Avenue in 1917 as a member of the Women's Political Equality League.[3]

In a 1914 issue of The Chinese Students' Monthly, Lee wrote that feminism is “the extension of democracy or social justice and equality of opportunities to women”.[16] She continued to write articles throughout college, calling for gender equality but also began giving speeches. At the Suffrage Workshop in 1915, Lee gave a speech that was covered in the New York Times. The speech was titled "China's Submerged Half" and stated:

The welfare of China and possibly its very existence as an independent nation depend on rendering tardy justice to its womankind. For no nation can ever make real and lasting progress in civilization unless its women are following close to its men if not actually abreast with them.

— Mabel Ping-Hua Lee[15]

.jpg.webp)

In 1917, women won the right to vote in the state of New York, amending the state's constitution. However, Lee herself was unable to exercise that constitutional right because of the discriminatory federal naturalization laws of the time. The Chinese Exclusion Act, which was not repealed until 1943, barred Chinese immigrants from the process of naturalization. While Lee fought for equality and the right to vote, she and other immigrant women, were unable to reap the benefits until years later.[3][6] Her mother supported the suffrage movement but also could not vote.[14] It is unclear if Lee ever voted or if she became a US citizen.[21]

According to the only directly attributed quote from Lee in a 1912 New-York Tribune article about her, entitled Chinese Girl Wants Vote, Lee's definition of suffrage was framed in the context of its benefit to the family, specifically a husband.

"How can a marriage be happy?" she asked, "unless the wife is educated enough to understand and sympathize with her husband in his business and intellectual interests? That seems to be the great difference between the American and the Chinese ideals of education. The Chinese ideal is to make the girl a comfort and delight to her parents and later to her husband. The American ideal is to help the girl toward her own improvement for her own pleasure. It seems to me that each nation has something to learn from the other."[11]

In a later essay, The Meaning of Woman Suffrage Lee authored and published in The Chinese students' monthly, while providing arguments in favor of suffrage for the "interest" of the race, community, woman herself, husband, and child, she articulated her definition of the feminist movement as follows.

"We believe in the idea of democracy; woman suffrage or the feminist movement (of which woman suffrage is a fourth part) is the application of democracy to women. ... The fundamental principle of democracy is equality of opportunity ... It means an equal chance for each man to show what his merits are. ... the feminists want nothing more than the equality of opportunity for women to prove their merits and what they are best suited to do."[22]

Ministry

When Mabel Lee's father died from a heart attack in 1924, she took over his role as head of the Baptist mission in Chinatown at the age of 28.[23] Although this was meant to be a temporary position, it would become her life's work. Lee traveled three times to China during the 1920s and 1930s, and even had job offers awaiting her there, but she eventually chose to settle permanently in New York and focus on her father's church.[12]

Lee began raising funds from the American Baptist Home Mission Society and local Chinese American organizations to help fund a Chinese Christian Center in memory of her father. In 1926, she purchased a building for this community center at 21 Pell Street in Chinatown. The center offered English classes, a medical clinic, and a kindergarten. Lee believed that an independent Chinese church was crucial for providing support and a feeling of freedom to its community members, who were otherwise marginalized and oppressed in American society.[15]

Lee's view that there needed to be a Chinese Christianity and not a European American Protestantism sometimes brought her into conflict with the larger white-led Baptist mission in New York City. In 1954, Lee was able to secure the title of the 21 Pell Street property solely under First Chinese Baptist Church which from then on became fully independent. Paradoxically, this independence coincided with the increasing secularization of younger generations of Chinese Americans, and led to dwindling membership at the church.[4][14][15] However, under her leadership the church became the first "self-supporting Chinese church in America."[12] As a bilingual Chinese-American, Lee was able to provide significant assistance to the working class Chinese immigrant community by providing classes teaching the English language, typewriting, and broadcasting and carpentry among other useful skills. Lee even participated by preaching and taught kindergarten and Sunday school. In many ways the church functioned as an underground social service center for the Chinese community.[12][24]

The First Chinese Baptist Church is still standing and continues to offer the social services Lee started and strives to maintain the community's civil rights she fought for.[6]

Personal life and death

Mabel Lee never married and managed to maintain economic independence. This was a lifestyle only women with higher education could have had during Lee's lifetime.[13] She never went back to her academic studies, even after friend Hu Shih suggested she continue her "scholastic and intellectual interests".[15] Lee chose to dedicate her life to Christ and the Chinatown community until her death in 1966. She was 70 years old.[16][14]

Legacy

In November 2017, a motion was introduced in Congress by Rep. Nydia Velazquez to rename the Chinatown Station U.S. Post Office at 6 Doyers Street in honor of Mabel Lee.[25] The bill was passed in the U.S. House of Representatives in March 2018.[26] There was a dedication ceremony at the First Chinese Baptist Church at 21 Pell St. on December 3, 2018, at 11am.[27]

In March 2018, Lee was honored as one of a featured series of women's suffrage activists displayed on LinkNYC kiosks in New York City as part of a partnership with the Museum of the City of New York.[28]

Lee was named a National Women's History Alliance honoree in 2020.[29] Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was featured in the New York Times Overlooked series obituaries on remarkable people whose deaths initially went unreported in newspaper in September 2020.[30]

References

- ↑ "胡适心中的圣女" (in Chinese). Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Biography: Mabel Ping-Hua Lee". Biography: Mabel Ping-Hua Lee. Retrieved 2021-08-11.

- 1 2 3 4 "Beyond Suffrage: "Working Together, Working Apart" How Identity Shaped Suffragists' Politics". Museum of the City of New York. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- 1 2 Tseng, Timothy (2002). "Unbinding Their Souls: Chinese Protestant Women in Twentieth-Century America". In Bendroth, Margaret Lamberts; Brereton, Virginia Lieson (eds.). Women and Twentieth-Century Protestantism. University of Illinois Press. pp. 136–163. ISBN 9780252069987.

- ↑ "How Columbia Suffragists Fought for the Right of Women to Vote". Columbia Magazine. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "New York City's Chinatown Post Office Named in Honor of Dr. Mabel Lee '1916 | Barnard College". barnard.edu. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ↑ "The Magnuson Act". www.fgcu.edu.

- ↑ Khan, Brooke (5 November 2019). Home of the Brave : An American History Book for Kids : 15 Immigrants Who Shaped U.S. History. López de Munáin, Iratxe, 1985–. Emeryville, California. ISBN 978-1-64152-780-4. OCLC 1128884800.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Who's who of the Chinese Students in America. Lederer, Street & Zeus Company. 1921. p. 52.

Ping-Hua Lee canton china.

- 1 2 Lee, Mabel Ping-hua (1921). The Economic History of China: With Special Reference to Agriculture. Columbia University.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chinese Girl Wants Vote". New-York Tribune. April 13, 1912. ISSN 1941-0646. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Tseng, Timothy (June 1, 2017). "Chinatown's Suffragist, Pastor, and Community Organizer". Christianity Today. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Xiao, Yue (September 28, 2018). Chinese economic development and Chinese women economists from The Routledge Handbook of the History of Women's Economic Thought Routledge. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315723570-16. ISBN 9781138852341. S2CID 159105581.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brooks, Charlotte. "#20: Suffragist Landmark » Asian American History in NYC". blogs.baruch.cuny.edu. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tseng, Timothy (1996). "Dr. Mabel Lee: The Intersticial Career of a Protestant Chinese American Woman, 1924–1950" (PDF). Presented at the 1996 Organization of American Historians Meeting.

- 1 2 3 4 May, Grace (2016). "William Carey International Development Journal : 3a. Leading Development at Home: Dr. Mabel Ping Hua Lee (1896–1966)". www.wciujournal.org. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ↑ Lindley, Susan Hill (2008). The Westminster Handbook to Women in American Religious History. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 130.

- ↑ "Asian American Legacy: Dr. Mabel Lee". Tim Tseng. December 13, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ↑ Tinker, Catherine (2017). "Annie Rensselaer Tinker (1884–1924) of East Setauket and NYC: Philanthropist, Suffragist, WWI Volunteer in Europe". Long Island History Journal. 26 (1). ISSN 0898-7084. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ↑ Chapman, Mary; Mills, Angela (2011). Treacherous Texts: U.S. Suffrage Literature, 1846–1946. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813549590.

- ↑ "Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ↑ Lee, Mabel (May 1914). "The Meaning of Woman Suffrage". The Chinese Students' Monthly. V.9:6–8. 9 (7): 526–531. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ↑ Hall, Bruce (January 15, 2002). Tea That Burns: A Family Memoir of Chinatown. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743236591.

- ↑ Chau, Lotus. "Chinatown Post Office Named for Mabel Lee". Voices of NY. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ↑ "Velazquez Moves to Rename Doyers Street Post Office For Suffragette Mabel Lee | The Lo-Down : News from the Lower East Side". The Lo-Down : News from the Lower East Side. November 29, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ↑ Perler, Elie (March 26, 2018). "Doyers Street Post Office Edges Closer to Honoring Chinese American Suffragette". Bowery Boogie. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Dedication For Chinatown's Mabel Lee Post Office Takes Place This Morning". The Lo-Down : News from the Lower East Side. December 3, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ↑ Warerkar, Tanay. "LinkNYC and Museum of the City of New York team up to honor women activists". Curbed NY. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ↑ "2020 Honorees". National Women's History Alliance. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ↑ Yang, Jia Lynn (2020-09-19). "Overlooked No More: Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, Suffragist With a Distinction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-07-23.