A Link at Third Avenue and 16th Street in Manhattan | |

| Founded | November 7, 2014 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | New York City, New York, U.S. |

Area served | New York metropolitan area |

| Brands | LinkNYC |

| Services | Wireless communication |

| Owner | Intersection (CityBridge consortium) Qualcomm CIVIQ Smartscapes |

| Website | link |

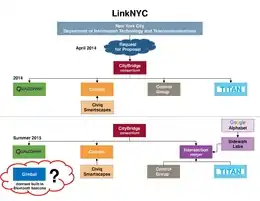

LinkNYC is the New York City branch of an international infrastructure project to create a network covering several cities with free Wi-Fi service. The office of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the plan on November 17, 2014, and the installation of the first kiosks, or "Links," started in late 2015. The Links replace the city's network of 9,000 to 13,000 payphones, a contract for which expired in October 2014. The LinkNYC kiosks were devised after the government of New York City held several competitions to replace the payphone system. The most recent competition, in 2014, resulted in the contract being awarded to the CityBridge consortium, which comprises Qualcomm; Titan and Control Group, which now make up Intersection; and Comark.

All of the 9.5-foot-tall (2.9 m) Links feature two 55-inch (140 cm) high-definition displays on their sides; Android tablet computers for accessing city maps, directions, and services, and making video calls; two free USB charging stations for smartphones; and a phone allowing free calls to all 50 states and Washington, D.C. The Links also provide the ability to use calling cards to make international calls, and each Link has one button to call 9-1-1 directly. Since 2022, CityBridge has also installed 32-foot-tall (9.8 m) poles under the Link5G brand, which provide both Wi-Fi and 5G service.

The project brings free, encrypted, gigabit wireless internet coverage to the five boroughs by converting old payphones into Wi-Fi hotspots where free phone calls could also be made. As of 2020, there are 1,869 Links citywide; eventually, 7,500 Links are planned to be installed in the New York metropolitan area, making the system the world's fastest and most expansive. Intersection has also installed InLinks in cities across the UK. The Links are seen as a model for future city builds as part of smart city data pools and infrastructure.

Since the Links' deployment, there have been several concerns about the kiosks' features. Privacy advocates have stated that the data of LinkNYC users can be collected and used to track users' movements throughout the city. There are also concerns with cybercriminals possibly hijacking the Links, or renaming their personal wireless networks to the same name as LinkNYC's network, in order to steal LinkNYC users' data. In addition, prior to September 2016, the tablets of the Links could be used to browse the Internet. In summer 2016, concerns arose about the Link tablets' browsers being used for illicit purposes; despite the implementation of content filters on the kiosks, the illicit activities continued, and the browsers were disabled.

History

Payphones and plans for reuse

In 1999, thirteen companies signed a contract that legally obligated them to maintain New York City's payphones for fifteen years.[1] In 2000, the city's tens of thousands of payphones were among the 2.2 million payphones spread across the United States.[2] Since then, these payphones' use had been declining with the advent of cellphones.[1] As of July 2012, there were 13,000 phones in over 10,000 individual locations;[1] that number had dropped to 9,133 phones in 7,302 locations by April 2014,[3] at a time when the number of payphones in the United States had declined more than 75 percent, to 500,000.[2] The contract with the thirteen payphone operators was set to expire in October 2014, after which time the payphones' futures were unknown.[1][3]

In July 2012, the New York City government released a public request for information, asking for comments about the future uses for these payphones.[1] The RFI presented questions such as "What alternative communications amenities would fill a need?"; "If retained, should the current designs of sidewalk payphone enclosures be substantially revised?"; and "Should the current number of payphones on City sidewalks change, and if so, how?".[1] Through the RFI, the New York City government sought new uses for the payphones, including a combination of "public wireless hotspots, touch-screen wayfinding panels, information kiosks, charging stations for mobile communications devices, [and] electronic community bulletin boards,"[1] all of which eventually became the features of the kiosks that were included in the LinkNYC proposal.[2][4][5]

In 2013, a year before the payphone contract was set to expire, there was a competition that sought ideas to further repurpose the network of payphones.[6] The competition, held by the administration of Michael Bloomberg, expanded the idea of the pilot project.[6] There were 125 responses that suggested a Wi-Fi network, but none of these responses elaborated on how that would be accomplished.[7][8]

Previous free Wi-Fi projects

In 2012, the government of New York City installed Wi-Fi routers at 10 payphones in the city (seven in Manhattan, two in Brooklyn, and one in Queens[9]) as part of a pilot project. The Wi-Fi was free of charge and available for use at all times.[6][9] The Wi-Fi signal was detectable from a radius of a few hundred feet (about 100m). Two of New York City's largest advertising companies—Van Wagner and Titan, who collectively owned more than 9,000 of New York City's 12,000 payphones at the time—paid $2,000 per router,[6] with no monetary input from either the city or taxpayers.[9] While the payphones participating in the Wi-Fi pilot project were poorly marked, the Wi-Fi offered at these payphones was significantly faster than some of the other free public Wi-Fi networks offered elsewhere.[9]

The Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem received free Wi-Fi starting in late 2013.[10] Routers were installed in three phases within a 95-block area between 110th Street, Frederick Douglass Boulevard, 138th Street, and Madison Avenue. Phase 1, from 110th to 120th Streets, finished in 2013; Phase 2, from 121st to 126th Street, was expected to be complete in February 2014; and Phase 3, the remaining area, was supposed to be finished by May 2014.[10] The network was estimated to serve 80,000 Harlemites, including 13,000 in public housing projects[10] who may have otherwise not had broadband internet access at home.[11][12] At the time, it was dubbed the United States' most expansive "continuous free public Wi-Fi network."[10]

Bids

On April 30, 2014, the New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DOITT) requested proposals for how to convert the city's over 7,000 payphones into a citywide Wi-Fi network.[7][8] A new competition was held, with the winner standing to receive a 12-year contract to maintain up to 10,000 communication points.[7][8][13] The communication points would tentatively have free Wi-Fi service, advertising, and free calls to at least 9-1-1 (the emergency service) or 3-1-1 (the city information hotline).[2][3]

The contract would require the operator, or the operating consortium, to pay "$17.5 million or 50 percent of gross revenues, whichever is greater" to the City of New York every year. The communication points could be up to 10 ft 3 in (3.12 m) tall, compared to the 7 ft 6 in (2.29 m) height of the phone booths; however, the advertising space on these points would only be allowed to accommodate up to 21.3 square feet (1.98 m2) of advertisements, or roughly half the maximum of 41.6 square feet (3.86 m2) of the advertising space allowed on existing phone booths.[3] There would still need to be phone service at these Links because the payphones are still used often: collectively, all of New York City's nearly 12,000 payphones were used 27 million times in 2011, amounting to each phone being used about 6 times per day.[1]

In November 2014, the bid was awarded to the consortium CityBridge, which consists of Qualcomm, Titan, Control Group, and Comark.[2][13][14][15][16] In June 2015, Control Group and Titan announced that they would merge into one company called Intersection. Intersection is being led by a Sidewalk Labs-led group of investors who operate the company as a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc. that focuses on solving problems unique to urban environments.[17][18][19] Daniel L. Doctoroff, the former CEO of Bloomberg L.P. and former New York City Deputy Mayor for Economic Development and Rebuilding, is the CEO of Sidewalk Labs.[20]

Installation of kiosks

Initial kiosks

.jpg.webp)

CityBridge announced that it would be setting up about 7,000 kiosks, called "Links," near where guests could use the LinkNYC Wi-Fi. Coverage was set to be up by late 2015, starting with about 500 Links in areas that already have payphones, and later to other areas.[21] These Links were to be placed online by the end of the year.[16] The project would require the installation of 400 miles (640 km) of new communication cables.[4] The Links would be built in coordination with borough presidents, business improvement districts, the New York City Council, and New York City community boards.[14] The project is expected to create up to 800 jobs, including 100 to 150 full-time jobs at CityBridge as well as 650 technical support positions.[2][14] Of the LinkNYC plans, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio said,

With this proposal for the fastest and largest municipal Wi-Fi network in the world – accessible to and free for all New Yorkers and visitors alike – we're taking a critical step toward a more equal, open and connected city – for every New Yorker, in every borough.[14]

In December 2014, the network was approved by New York City's Franchise and Concession Review Committee.[22] Installation of two stations on Third Avenue—at 15th and 17th Streets[23]—began on December 28, 2015,[24] followed by other Links on Third Avenue below 58th Street,[25][26] as well as on Eighth Avenue.[26] After some delays, the first Links went online in January 2016.[5][25][27] The public network was announced in February 2016.[28] Locations like St. George, Jamaica, South Bronx, and Flatbush Avenue were prioritized for LinkNYC kiosk installations, with these places receiving Links by the end of 2016.[28]

The vast majority of the payphones were to be demolished and replaced with Links.[2][25][26][28] However, three[2][4][13] or four[29] banks of payphones along West End Avenue in the Upper West Side are expected to be preserved rather than being replaced with Links.[2][4][13][29] These payphones are the only remaining fully enclosed payphones in Manhattan.[29][30] The preservation process includes creating new fully enclosed booths for the site, which is a difficulty because that specific model of phone booths is no longer manufactured.[29] The New York City government and Intersection agreed to preserve these payphones because of their historical value, and because they were a relic of the Upper West Side community, having been featured in the 2002 movie Phone Booth and the 2010 book "The Lonely Phone Booth."[29]

Expansion and issues

By mid-July 2016, the planned roll-out of 500 hubs throughout New York City was to occur,[27] though the actual installation proceeded at a slower rate.[31] As of September 2016, there were 400 hubs in three boroughs,[31] most of which were in Manhattan, although there were at least 25 hubs in the Bronx and several additional hubs in Queens.[32] In November 2016, the first two Links were installed in Brooklyn, with plans to install nine more Links in various places around Brooklyn before year's end.[33] Around this time, Staten Island received its first Links, which were installed in New Dorp.[33] The Links were being installed at an average pace of ten per day throughout the boroughs[26] with a projected goal of 500 hubs by the end of 2016.[25] By July 2017, there were 920 Links installed across the city.[34] This number had increased to 1,250 by January 2018,[35] and to 1,600 by September 2018.[36]

As originally planned, there would be 4,550 hubs by July 2019[37] and 7,500 hubs by 2024,[25][26][28] which would make LinkNYC the largest and fastest public, government-operated Wi-Fi network in the world.[2][7][13][14][23] Slightly more than half, or 52%, of the hubs would be in Manhattan and the rest would be in the outer boroughs.[26] There would be capacity for up to 10,000 Links within the network, as per the contract.[13][16][28] The total cost for installation is estimated at more than $200 million.[25][26] The eventual network includes 736 Links in the Bronx, 361 of which will have advertising and fast network speeds; as well as over 2,500 in Manhattan, most with advertising and fast network speeds.[38] By December 2019, only 1,774 LinkNYC kiosks had been installed across the city; the kiosks were largely concentrated in wealthy neighborhoods Manhattan, although Harlem, the South Bronx, and Queens also had several kiosks.[39]

CityBridge had installed 1,869 kiosks by May 2020.[40] Most of the kiosks were in Manhattan. CityBridge had only provided three-fifths the number of kiosks that it had been expected to provide by that time.[40][41] New York state comptroller Thomas DiNapoli released a report in 2021, finding that 86 of the city's 185 ZIP Codes had kiosks; Manhattan was the only borough that had LinkNYC kiosks in the vast majority of its ZIP Codes.[40]

Implementation of 5G poles

_02_-_Link5G.jpg.webp)

In October 2021, CityBridge submitted designs to the New York City Public Design Commission for the installation of 32-foot-tall (9.8 m) poles, capable of transmitting 5G wireless signals, under the Link5G brand.[42] The Public Design Commission initially only approved the construction of Link5G poles in commercial and industrial neighborhoods.[42][43] The first such pole was installed at the intersection of Hunters Point Avenue and 30th Place in Long Island City, Queens, in March 2022 and was used for testing.[44] As part of an agreement with the city government, over 2,000 poles were to be installed in portions of the city that lacked reliable internet service.[41][45] Under the agreement with CityBridge, the city would receive eight percent of the first $200 million in profits from the Link5G project, as well as half of all revenue above $200 million.[41] The first publicly accessible pole was installed in Morris Heights, Bronx, in July 2022.[43][46] By the end of the year, CityBridge had installed 26 Link5G poles citywide.[47]

As additional poles were rolled out across the city in 2023, many residents expressed concerns about the Link5G poles' appearance and height; some opponents also cited misinformation related to 5G technology.[48][49] Neighborhoods such as the West Village[50] and the Upper East Side passed regulations opposing the Link5G poles.[48] Conversely, city officials and businesses supported the installation of the poles.[49] Following a letter from U.S. representative Jerrold Nadler,[51] the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ruled in April 2023 that the poles needed to undergo environmental and historic-preservation reviews.[52][53]

Description

Links

The Links are 9.5 feet (2.9 m) tall, and are compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.[14][25] There are two 55-inch (140 cm) high-definition displays on each Link[2][4][24][54] for advertisements[2][15][16][21] and public service announcements.[2][5] There is an integrated Android tablet embedded within each Link, which can be used to access city maps, directions, and services, as well as make video calls;[2][4][5] they were formerly also available to allow patrons to use the internet, but these browsers have now been disabled due to abuse (see below).[31]

Each Link includes two free USB charging stations for smartphones as well as a phone that allows free calls to all 50 states and to Washington, D.C.[36] The Links allow people to make either phone calls (using the keypad and the headphone jack to the keypad's left), or video calls (using the tablet).[2][4][5][26] Vonage provides this free domestic phone call service as well as the ability to make international calls using calling cards.[20] The Links feature a red 9-1-1 call button between the tablet and the headphone jack,[4][55] and they can be used to call the information helpline 3-1-1.[4][14][55]

The Links can be used for completing simple time-specific tasks[35] such as registering to vote.[56] In April 2017, the Links were equipped with another app, Aunt Bertha, which could be utilized to find social services such as food pantries, financial aid, and emergency shelter.[57] The Links sometimes offer eccentric apps, such as an app to call Santa's voice mail that was enabled in December 2017.[35] In October 2019, a video relay service for deaf users was added to the Links.[58]

The Wi-Fi technology comes from Ruckus Wireless and is enabled by Qualcomm's Vive 802.11ac Wave 2 4x4 chipsets.[5] The Links' operating system runs on the Qualcomm Snapdragon 600 processor and the Adreno 320 graphics processing unit.[54] The Links' hardware and software can handle future upgrades. The software will be updated until at least 2022, but Qualcomm has promised to maintain the Links for the rest of their service lives.[54]

Links are cleaned twice weekly, with LinkNYC staff removing vandalism and dirt from the Links. Each Link has cameras and over 30 vibration sensors to sense if the kiosk has been hit by an object.[26][59] A separate set of sensors also detects if the USB ports are tampered with.[59] If either the vibration sensors or the USB port sensors detect tampering, an alert is displayed at LinkNYC headquarters that the specific part of the Link has been affected.[59] All of the Links have a backup battery power supply that can last for up to 24 hours if a long-term power outage were to occur.[28] This was added to prevent interruption of phone service, as happened in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which caused power outages citywide, especially to the city's payphones (which were connected to the municipal power supply of New York City).[2] Antenna Design helped with the overall design of the kiosks,[14][16] which are produced by Comark subsidiary Civiq.[4][60]

Advertising screens

New York City does not pay for the system because CityBridge oversees the installation, ownership, and operations, and is responsible for building the new optic infrastructure under the streets.[61] CityBridge stated in a press release that the network would be free for all users, and that the service would be funded by advertisements.[2][15][16][21] This advertising will provide revenue for New York City as well as for the partners involved in CityBridge.[61]

The advertising is estimated to bring in over $1 billion in revenue over twelve years, with the City of New York receiving over $500 million, or about half of that amount.[25][26] Technically, the LinkNYC network is intended to act as a public internet utility with advertising services.[4] However, in four of the first five years the Links have been active, actual revenue fell short of goals. This is partially due to the fact that some local small businesses and non-profits were given advertisement space for free.[62]

The Links' advertising screens also display "NYC Fun Facts", one-sentence factoids about New York City, as well as "This Day in New York" facts and historic photographs of the city, which are shown between advertisements.[35][63] In April 2018, some advertising screens started displaying real-time bus arrival information for nearby bus routes, using data from the MTA Bus Time system.[64][65] Other things displayed on Links include headlines from the Associated Press, as well as weather information, comics, contests, and "content collaborations" where third-party organizations display their own information.[63]

Links in some areas, especially lower-income and lower-traffic areas, are expected to not display advertisements because it is not worthwhile for CityBridge to advertise in these areas.[38] Controversially, the Links that lack advertising are expected to exhibit network speeds that may be as slow as one-tenth of the network speeds of advertisement-enabled Links. As of 2014, wealthier neighborhoods in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens were expected to have the most Links with advertisements and fast network speeds, while poorer neighborhoods and Staten Island would get slower Links with no advertising.[38] CityBridge sold fewer advertisements than expected, and it defaulted on $70 million owed to the city in July 2021.[40][66]

5G poles

CityBridge began installing Link5G poles across the city in 2022. Each pole measures 32 feet (9.8 m) tall, more than three times as high as the original kiosks;[41][45] the FCC had mandated that the poles be at least 19.5 feet (5.9 m) high.[67] In contrast to the kiosks, the Link5G poles were supposed to be installed in neighborhoods without good internet service; ninety percent of the poles were to be placed in the outer boroughs or in Upper Manhattan north of 96th Street.[68]

The lower sections of many of the poles have tablets, USB charging ports, 9-1-1 call buttons, and advertising displays, similar to the original kiosks. The upper portions of each pole contain 5G equipment installed by telecommunications companies, which can rent space within the poles from CityBridge.[41] The 5G antennas measure 63 inches (1,600 mm) tall and 21 feet (6.4 m) across. Next to each antenna is a box measuring 38 by 16 by 14 inches (970 by 410 by 360 mm).[45] There are five transmitters atop each pole, measuring at least 29 inches (740 mm) tall.[67] Although Wi-Fi service from the 5G poles is provided free of charge, users have to pay their telecom companies to receive 5G service.[41] The poles also have cameras on them, but the cameras are not operational at all times.[43][68]

Network

According to its specifications, the Links' Wi-Fi will cover a radius of 150 feet (46 m)[4][5][7][16][21] to 400 feet (120 m).[4][23][26] The Links' Wi-Fi is capable of running at 1 gigabit per second or 1000 megabits per second,[2][16][21][23] more than 100 times faster than the 8.7 megabit per second speed of the average public Wi-Fi network in the United States.[23][26] LinkNYC's routers have neither a bandwidth cap nor a time limit for usage, meaning that users can use LinkNYC Wi-Fi for as long as they need to.[26] The free phone calls are also available for unlimited use.[26] The network is only intended for use in public spaces,[26] though this may be subject to change in the future.[4] In the future, the LinkNYC network could also be used to "connect lighting systems, smart meters, traffic networks, connected cameras and other IoT systems,"[54] as well as for utility monitoring and for 5G installations.[4]

CityBridge emphasized that it takes security and privacy seriously "and will never sell any personally identifiable information or share with third parties for their own use".[15]: 2 Aside from the unsecured network that devices can directly connect to, the Links provide an encrypted network that shields communications from eavesdropping within the network. There are two types of networks: a private (secured WPA/WPA2) network called "LinkNYC Private," which is available to iOS devices with iOS 7 and above; and a public network called "LinkNYC Free Public Wi-Fi," which is available to all devices but is only protected by the device's browser.[69][70]

Private network users will have to accept a network key in order to log onto the LinkNYC Wi-Fi.[59][70] This would make New York City one of the first American municipalities to have a free, encrypted Wi-Fi network,[16] as well as North America's largest.[4] LinkNYC would also be the fastest citywide ISP in the world, with download and upload speeds between 15 and 32 times faster than on free networks at Starbucks, in LaGuardia Airport, and within New York City hotels.[70]

Originally, the CityBridge consortium was supposed to include Transit Wireless, which maintains the New York City Subway's wireless system.[14] However, as neither company mentioned each other on their respective websites, one communications writer speculated that the deal had either not been implemented yet or had fallen through. Transit Wireless stated that "those details have not been finalized yet", and CityBridge "promised to let [the writer] know when more information is available."[16]

The network is extremely popular, and by September 2016, around 450,000 unique users and over 1 million devices connected to the Links in an average week.[71] The Links had been used a total of more than 21 million times by that date.[72] This had risen to over 576,000 unique users by October 4,[56] with 21,000 phone calls made in the previous week alone.[73] By January 2018, the number of calls registered by the LinkNYC system had risen to 200,000 per month, or 50,000 per week on average. There were also 600,000 unique users connecting to the Links' Wi-Fi or cellular services each week.[35] The LinkNYC network exceeded 500,000 average monthly calls, 1 billion total sessions, and 5 million monthly users in September 2018.[36]

One writer for the Motherboard website observed that the LinkNYC network also helped connect poor communities, as people from these communities come to congregate at the Links.[74] This stems from the fact that the network provides service to all New Yorkers regardless of income, but it especially helps residents who would have otherwise used their smartphones for internet access using 3G and 4G.[28] The New York City Bureau of Policy and Research published a report in 2015 that stated that one-fourth of residents do not have home broadband internet access, including 32 percent of unemployed residents.[12]

As of January 2018, the most-dialed number on the LinkNYC network was the helpline for the state's electronic benefit transfer system, which distributes food stamps to low-income residents.[35] The LinkNYC network is seen as only somewhat mitigating this internet inequality, as many poor neighborhoods, like some in the Bronx, will get relatively few Links.[74] LinkNYC is seen as an example of smart city infrastructure in New York City, as it is a technologically advanced system that helps enable technological connectivity.[4][74]

Concerns

Tracking

The deployment of the Links and the method, process, eventual selection, and ownership of entities involved in the project has come under scrutiny by privacy advocates, who express concerns about the terms of service, the financial model, and the collection of end users' data.[60][75][76][77] These concerns are aggravated by the involvement of Sidewalk Labs, which belongs to Google's holding company, Alphabet Inc.[60] Google already has the ability to track the majority of all website visits,[78] and LinkNYC could be used to track people's movements.[60] Nick Pinto of the Village Voice, a Lower Manhattan newspaper, wrote:

Google is in the business of taking as much information as it can get away with, from as many sources as possible, until someone steps in to stop it. ... But LinkNYC marks a radical step even for Google. It is an effort to establish a permanent presence across our city, block by block, and to extend its online model to the physical landscape we humans occupy on a daily basis. The company then intends to clone that system and start selling it around the world, government by government, to as many as will buy.[60]

.jpg.webp)

In March 2016, the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU), the New York City office of the American Civil Liberties Union, wrote a letter to Mayor de Blasio outlining their privacy concerns.[76][77] In the letter, representatives for the NYCLU wrote that CityBridge could be retaining too much information about LinkNYC users. They also stated that the privacy policy was vague and needed to be clarified. They recommended that the privacy policy be rewritten so that it expressly mentions whether the Links' environmental sensors or cameras are being used by the NYPD for surveillance or by other city systems.[76] In response, LinkNYC updated its privacy policy to make clear that the kiosks do not store users' browsing history or track the websites visited while using LinkNYC's Wi-Fi,[79] a step that NYCLU commended.[80]

In an unrelated incident, Titan, one of the members of CityBridge, was accused of embedding Bluetooth radio transmitters in their phones, which could be used to track phone users' movements without their consent.[61][81] These beacons were later found to have been permitted by the DOITT, but "without any public notice, consultation, or approval", so they were removed in October 2014.[61] Despite the removal of the transmitters, Titan is proposing putting similar tracking devices on Links, but if the company decides to go through with the plan, it has to notify the public in advance.[61]

In 2018, a New York City College of Technology undergraduate student, Charles Myers, found that LinkNYC had published folders on GitHub titled "LinkNYC Mobile Observation" and "RxLocation". He shared these with The Intercept website, which wrote that the folders indicated that identifiable user data was being collected, including information on the user's coordinates, web browser, operating system, and device details, among other things. However, LinkNYC disputed these claims and filed a Digital Millennium Copyright Act claim to force GitHub to remove files containing code that Meyer had copied from LinkNYC's GitHub account.[82]

Other privacy issues

According to LinkNYC, it does not monitor its kiosks' Wi-Fi, nor does it give information to third parties.[26] However, data will be given to law enforcement officials in situations where LinkNYC is legally obliged.[23][77] Its privacy policy states that it can collect personally identifiable information (PII) from users to give to "service providers, and sub-contractors to the extent reasonably necessary to enable us provide the Services; a third party that acquires CityBridge or a majority of its assets [if CityBridge was acquired by that third party]; a third party with whom we must legally share information about you; you, upon your request; [and] other third parties with your express consent to do so."[83] Non-personally identifiable information can be shared with service providers and advertisers.[2][83] The privacy policy also states that "in the event that we receive a request from a governmental entity to provide it with your Personally [sic] Information, we will take reasonable attempts to notify you of such request, to the extent possible."[26][83]

There are also concerns that despite the WPA/WPA2 encryption, hackers may still be able to steal other users' data, especially since the LinkNYC Wi-Fi network has millions of users. To reduce the risk of data theft, LinkNYC is deploying a better encryption system for devices that have Hotspot 2.0.[26][28] Another concern is that hackers could affect the tablet itself by redirecting it to a malware site when users put in PII, or adding a keystroke logging program to the tablets.[59] To protect against this, CityBridge places in "a series of filters and proxies" that prevents malware from being installed; ends a session when a tablet is detected communicating with a command-and-control server; and resets the entire kiosk after 15 seconds of inactivity.[59][69] The USB ports have been configured so that they can only be used to charge devices. However, the USB ports are still susceptible to physical tampering with skimmers, which may lead to a user's device getting a malware infection while charging; this is prevented by the more than 30 anti-vandalism sensors on each Link.[59][69]

Yet another concern is that a person may carry out a spoofing attack by renaming their personal Wi-Fi network to "LinkNYC." This is potentially dangerous since many electronic devices tend to automatically connect to networks with a given name, but do not differentiate between the different networks.[59] One reporter for The Verge suggested that to circumvent this, a person could turn off their mobile device's Wi-Fi while in the vicinity of a kiosk, or "forget" the LinkNYC network altogether.[59]

The cameras on the top of each kiosk's tablet posed a concern in some communities where these cameras face the interiors of buildings. However, as of July 2017, the cameras were not activated.[34]

Browser access and content filtering

In the summer of 2016, a content filter was set up on the Links to restrict navigation to certain websites, such as pornography sites and other sites with not safe for work (NSFW) content.[84] This was described as a problem especially among the homeless,[85] and at least one video showed a homeless man watching pornography on a LinkNYC tablet.[84] This problem has supposedly been ongoing since at least January 2016.[85] Despite the existence of the filter, Link users still found a way to bypass these filters.[69][71][86][87]

The filters, which consisted of Google SafeSearch as well as a web blocker that was based on the web blockers of many schools, were intentionally lax to begin with because LinkNYC feared that stricter filters that blocked certain keywords would alienate customers.[87] Other challenges included the fact that "stimulating" user-generated content can be found on popular, relatively interactive websites like Tumblr and YouTube; it is hard to block NSFW content on these sites, because that would entail blocking the entire website when only a small portion hosts NSFW content. In addition, it was hard, if not impossible, for LinkNYC to block new websites with NSFW content, as such websites are constantly being created.[87]

A few days after Díaz's and Johnson's statements, the web browsers of the tablets embedded into the Links were disabled indefinitely due to concerns of illicit activities such as drug deals and NSFW website browsing.[31][88] LinkNYC cited "lewd acts" as the reason for shutting off the tables' browsing capabilities.[86] One Murray Hill resident reported that a homeless man "enthusiastically hump[ed]" a Link in her neighborhood while watching pornography.[85] Despite the tablets being disabled, the 9-1-1 capabilities, maps, and phone calls would still be usable, and people can still use LinkNYC Wi-Fi from their own devices.[72][86][88]

The disabling of the LinkNYC tablets' browsers had stoked fears about further restrictions on the Links. The Independent, a British newspaper, surveyed some homeless New Yorkers and found that while most of these homeless citizens used the kiosks for legitimate reasons (usually not to browse NSFW content), many of the interviewees were scared that LinkNYC may eventually charge money to use the internet via the Links, or that the kiosks may be demolished altogether.[89] The Guardian, another British newspaper, came to a similar conclusion; one of the LinkNYC users they interviewed said that the Links are "very helpful, but of course bad people messed it up for everyone".[90] In a press release, LinkNYC refuted fears that service would be paywalled or eliminated, though it did state that several improvements, including dimming the kiosks and lowering maximum volumes, were being implemented to reduce the kiosks' effect on the surrounding communities.[72]

Immediately after the disabling of the tablets' browsing capabilities, reports of loitering near kiosks decreased by more than 80%.[56][73] By the next year, such complaints had dropped 96% from the pre-September 2016 figure.[91] The tablets' use, as a whole, has increased 12%, with more unique users accessing maps, phone calls, and 3-1-1.[56][73]

Nuisance complaints

There have been scattered complaints in some communities that the LinkNYC towers themselves are a nuisance. These complaints mainly have to do with loitering, browser access, and kiosk volume, the latter two of which the city has resolved.[34] However, these nuisance complaints are rare citywide; of the 920 kiosks installed citywide by then, there had been only one complaint relating to the kiosk design itself.[34]

In September 2016, the borough president of the Bronx, Rubén Díaz Jr., called on city leaders to take stricter action, saying that "after learning about the inappropriate and over-extended usage of Links throughout the city, in particular in Manhattan, it is time to make adjustments that will allow all of our city residents to use this service safely and comfortably."[71] City Councilman Corey Johnson said that some police officials had called for several Links in Chelsea to be removed because homeless men had been watching NSFW content on these Links while children were nearby.[31][92] Barbara A. Blair, president of the Garment District Alliance, stated that "people are congregating around these Links to the point where they're bringing furniture and building little encampments clustered around them. It's created this really unfortunate and actually deplorable condition."[31]

A related problem arising from the tablets' browser access was that even though the tablets were intended for people to use it for a short period of time, the Links began being "monopolized" almost as soon as they were unveiled.[71] Some people would use the Links for hours at a time.[31] Particularly, homeless New Yorkers would sometimes loiter around the Links, using newspaper dispensers and milk crates as "makeshift furniture" on which they could sit while using the Links.[31][74][92] The New York Post characterized the Links as having become "living rooms for vagrants".[93] As a result, LinkNYC staff were working on a way to help ensure that Links would not be monopolized by one or two people.[71][72] Proposals for solutions included putting time limits on how long the tablets could be used by any one person.[94]

Some people stated that the Links could also be used for loitering and illicit phone calls.[92][95] One Hell's Kitchen bar owner cited concerns about the users of a Link located right outside his bar, including a homeless man who a patron complained was a "creeper" watching animal pornography, as well as several people who made drug deals using the Link's phone capabilities while families were nearby.[95] In Greenpoint, locals alleged that after Links were activated in their neighborhood in July 2017, these particular kiosks became locations for drug deals; however, that particular Link was installed near a known drug den.[91]

Wider deployment

Intersection, in collaboration with British telecommunications company BT and British advertising agency Primesight, is also planning to install up to 850 Links in the United Kingdom, including in London, beginning in 2017. The LinkUK kiosks, as they will be called, are similar to the LinkNYC kiosks in New York City. These Links will replace some of London's iconic telephone booths due to these booths' age.[96][97][98] The first hundred Links would be installed in the borough of Camden.[96] The Links will have tablets, but they will lack web browsing capabilities due to the problems that LinkNYC faced in enabling the tablet browsers.[99][100]

In early 2016, Intersection announced that it could install about 100 Links in a mid-sized city in the United States, provided that it wins the United States Department of Transportation's Smart City Challenge.[101] Approximately 25 of that city's blocks will get the Links, which will be integrated with Sidewalk Labs' transportation data-analysis initiative, Flow.[101] In summer 2016, the city of Columbus, Ohio, was announced as the winner of the Smart City Challenge.[102] Intersection has proposed installing Links in four Columbus neighborhoods.[103]

In July 2017, the city of Hoboken, New Jersey, located across the Hudson River from Manhattan, proposed adding free Wi-Fi kiosks on its busiest pedestrian corridors. The kiosks, which are also a smart-city initiative, are proposed to be installed by Intersection.[104]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Request for Information Regarding the Future of Public Pay Telephones on New York City Sidewalks and Potential Alternative or Additional Forms of Telecommunications Facilities on New York City Sidewalks" (PDF). nyc.gov. Government of New York City. July 11, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 3, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Chowdhry, Amit (November 19, 2014). "Pay Phones In NYC To Be Replaced With Up To 10,000 Free Wi-Fi Kiosks Next Year". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Dunlap, David W. (April 30, 2014). "The 21st Century Is Calling, With Wi-Fi Hot Spots". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Stilson, Janet (February 15, 2016). "What It Means for Consumers and Brands That New York Is Becoming a 'Smart City'". AdWeek. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kleiman, Rob (January 19, 2016). "The first wave of high-speed public internet access via LinkNYC kiosks has arrived". psfk.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Abuelgasim, Fay (July 15, 2012). "Pay Phones Getting The WiFi Treatment". The Huffington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gould, Jessica (January 5, 2016). "Goodbye Pay Phones, Hello LinkNYC". WNYC. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 McCarthy, Tyler (May 8, 2014). "New York City Seriously Wants To Turn Pay Phones Into WiFi Hotspots". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Payphones Get an Upgrade with City's Free WiFi Pilot". MetroFocus. WNET. July 17, 2012. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Announcing the country's largest continuous free public WiFi network". nyc.gov. Government of New York City. December 10, 2013. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ Horn, Leslie (December 10, 2013). "Harlem Is Getting the Biggest Free Public Wi-Fi Network In the U.S." Gizmodo. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- 1 2 Stringer, Scott (September 2015). "Internet Inequality: Broadband Access in NYC" (PDF). nyc.gov. Office of the New York City Comptroller. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "New York City unveils the pay phone of the future—and it does a whole lot more than make phone calls". Washington Post. November 17, 2014. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "De Blasio Administration Announces Winner of Competition to Replace Payphones with Five-Borough Wi-Fi Network". nyc.gov. Government of New York City. November 17, 2014. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Gigabit Wi-Fi And that's just the beginning" (PDF). CityBridge. November 17, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Silly, Mari (June 25, 2015). "Who's Feeding Fiber to LinkNYC Hotspots?". Light Reading. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ↑ Dale, Brady (June 16, 2015). "Seven Urban Technologies Google-Backed Sidewalk Labs Might Advance". New York Observer. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Control Group and Titan Merge to form Intersection" (PDF) (Press release). June 23, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Google's Sidewalk Labs is taking over the plan to blanket NYC with free Wi-Fi". The Verge. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- 1 2 Crow, David (January 5, 2016). "First WiFi kiosks set to land on New York's streets". Financial Times. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Aguilar, Mario (November 17, 2014). "The Plan to Turn NYC's Old Payphones Into Free Gigabit Wi-Fi Hot Spots". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ↑ "DoITT - LinkNYC Franchises". nyc.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology & Telecommunications (DOITT). December 10, 2014. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Alba, Alejandro (January 5, 2016). "New York to start replacing payphones with Wi-Fi kiosks". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Brandom, Russell (December 28, 2015). "New York is finally installing its promised public gigabit Wi-Fi". The Verge. Archived from the original on December 29, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Crow, David (January 5, 2016). "The City's First Wi-Fi Kiosks Unveiled Today!". 6sqft.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Robbins, Christopher (January 5, 2016). "Brace For The "Fastest Internet You've Ever Used" At These Free Sidewalk Kiosks". Gothamist. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Brandom, Russell (January 19, 2016). "New York's first public Wi-Fi hubs are now live". The Verge. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Mayor de Blasio Announces Public Launch of LinkNYC Program". nyc.gov. Government of New York City. February 18, 2016. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kilgannon, Corey (February 10, 2016). "And Then There Were Four: Phone Booths Saved on Upper West Side Sidewalks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ↑ Carr, Nick (August 27, 2009). "The Last Phone Booths In Manhattan". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 McGeehan, Patrick (September 14, 2016). "Free Wi-Fi Was to Aid New Yorkers. An Unsavory Side Spurs a Retreat". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Find a Link". CityBridge / LinkNYC. Intersection. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 Fingas, Jon (November 14, 2016). "New York City's free gigabit WiFi comes to Brooklyn". Engadget. Archived from the original on December 12, 2016. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Frost, Mary (July 31, 2017). "LinkNYC kiosks not a hit with everyone". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Williams, Keith (2018). "What are those tall kiosks that have replaced pay phones in New York?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Wiggers, Kyle (September 29, 2018). "LinkNYC's 5 million users make 500,000 phone calls each month". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ↑ Otis, Ginger Adams (August 30, 2016). "Wi-Fi kiosks will replace Bronx pay phones under LinkNYC". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 4, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Greg B. (November 24, 2014). "EXCLUSIVE: De Blasio's Wi-Fi plan slower in poor nabes". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ Correal, Annie (December 6, 2019). "Just a Quarter of New York's Wi-Fi Kiosks Are Up. Guess Where". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "DiNapoli Examines Faltering LinkNYC Program". Office of the New York State Comptroller. July 30, 2021. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sandoval, Gabriel; McWhirter, Joshua (April 27, 2022). "Big Tech Pays to Supersize LinkNYC and Revive Broken Promise to Bridge Digital Divide". The City. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 Deffenbaugh, Ryan (October 18, 2021). "City commission questions design for 'giant' LinkNYC 5G kiosks". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Duggan, Kevin (July 10, 2022). "City boots up in the Bronx with massive new LinkNYC kiosks featuring 5G capability". amNewYork. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Failing Up: First Link5G 'Smart Pole' Stands Quietly in Queens". The City. March 20, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Stewart, Dodai (November 5, 2022). "What Are Those Mysterious New Towers Looming Over New York's Sidewalks?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ↑ Wassef, Mira (July 11, 2022). "NYC's first Link5G kiosk installed in the Bronx". PIX11. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ↑ Siff, Andrew (December 6, 2022). "More 5G Towers Are Coming to NYC — See Where They Are Being Built". NBC New York. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 Garber, Nick (December 16, 2022). "Towering Upper East Side 5G Poles Shot Down By Community Board". Upper East Side, NY Patch. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 Garber, Nick (June 8, 2023). "Hulking 5G towers get biz backing amid neighborhood opposition". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ↑ Anderson, Lincoln (February 22, 2023). "G shock: Rollout of jumbo Link5G towers is roiling the historic West Village". The Village Sun. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ↑ Parrott, Max (April 17, 2023). "Rep. Nadler calls for federal review of Manhattan's 5G poles". amNewYork. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Link5G Towers Must Pass Historic Preservation and Environmental Reviews, Says FCC". The City. April 26, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ↑ Sommerfeldt, Chris (April 26, 2023). "NYC's behemoth 5G towers haven't undergone required reviews, FCC says". New York Daily News. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Shah, Agam (March 7, 2016). "Users will get faster free Wi-Fi from hubs in New York". PCWorld. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Zeman, Eric (January 20, 2016). "LinkNYC WiFi Hotspots Kick Off". InformationWeek. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Pereira, Ivan (October 4, 2016). "LinkNYC: Over 576,000 have used free Wi-Fi at kiosks". am New York. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ↑ Bliss, Laura (April 13, 2017). "'Yelp for Social Services' Now Available on Hundreds of New York City Wi-Fi Kiosks". CityLab. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ↑ "LinkNYC Kiosks Now Accessible for the Deaf". www.ny1.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Carman, Ashley (January 20, 2016). "How secure are New York City's new Wi-Fi hubs?". The Verge. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pinto, Nick (July 6, 2016). "Google Is Transforming NYC's Payphones Into a 'Personalized Propaganda Engine'". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stuart, Tessa (November 19, 2014). "New Wi-Fi 'Payphones' May Include Controversial Location-Tracking Beacons". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on August 14, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ Voytko, Lisette (May 6, 2019). "Payphone-Replacing LinkNYC Kiosks Not Generating Projected Revenue". Gotham Gazette. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- 1 2 Wiggers, Kyle (March 28, 2019). "LinkNYC's 6 million users have used 8.6 terabytes of data". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ↑ Stremple, Paul (April 4, 2018). "Bus Time Pilot For LinkNYC Kiosks Misses The Mark - BKLYNER". BKLYNER. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ↑ Flamm, Matthew (April 4, 2018). "LinkNYC kiosks to double as bus countdown clocks". Crain's New York Business. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ↑ Deffenbaugh, Ryan (July 30, 2021). "Lack of oversight allowed LinkNYC to fall $70M behind". Crain's New York Business. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- 1 2 Combs, DeAnn (December 21, 2022). "LinkNYC 5G Poles Spreading Across Gotham". Inside Towers. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 Weaver, Shaye (July 11, 2022). "Thousands of 32-foot-tall 5G kiosks will be going up across NYC". Time Out New York. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Biersdorfer, J. D. (August 26, 2016). "Are the Free Wi-Fi Kiosks on New York Streets Safe?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Stern, Joanna (January 19, 2016). "The Future of Public Wi-Fi: What to Do Before Using Free, Fast Hot Spots". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on December 15, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chan, Shirley (September 12, 2016). "More lewd acts purportedly spotted at Manhattan Wi-Fi kiosks". New York's PIX11 / WPIX-TV. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Service Update". CityBridge / LinkNYC. Intersection. September 14, 2016. Archived from the original on October 14, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Fermino, Jennifer (October 4, 2016). "LinkNYC kiosks usage rises 12% month after web browsing disabled". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Huber, Linda (September 14, 2016). "Is New York City's Public Wi-Fi Actually Connecting the Poor?". motherboard.vice.com. Vice. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ Dean, Benjamin; Hirose, Mariko (July 24, 2016). "LinkNYC Spy Stations - from HOPE XI - LAMARR" (Livestream video). HOPE XI - The Eleventh HOPE Hackers On Planet Earth!. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Hirose, Mariko; Miller, Johanna (March 15, 2016). "Re: LinkNYC Privacy Policy" (PDF). www.nyclu.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Waddell, Kaveh. "Will New York City's Free Wi-Fi Help Police Watch You?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ Yu, Zhonghao; Macbeth, Sam; Modi, Konark; Pujol, Josep M. (2016). "Tracking the Trackers". Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web. Montreal, Canada: International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee. pp. 121–132. ISBN 978-1-4503-4143-1. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ↑ Intersection (December 20, 2018). "Privacy Policy". LinkNYC. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ↑ "City Strengthens Public Wi-Fi Privacy Policy After NYCLU Raises Concerns". NYCLU. March 17, 2017. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ↑ Brown, Stephen Rex (October 6, 2014). "Manhattan phone booths rigged to follow your every step". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Are New York's Free LinkNYC Internet Kiosks Tracking Your Movements?". The Intercept. September 8, 2018. Archived from the original on November 13, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "PUBLIC COMMUNICATIONS STRUCTURE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT: Exhibit 2 – Privacy Policy: CityBridge, LLC" (PDF). nyc.gov. Government of New York City. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Chung, Jen (July 28, 2016). "Yes, NYC's New WiFi Kiosks Are Still Being Used To View Porn". Gothamist. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 DeGregory, Priscilla; Rosenbaum, Sophia (September 11, 2016). "Bum caught masturbating in broad daylight next to Wi-Fi kiosk". New York Post. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Brodkin, Jon (September 14, 2016). "After "lewd acts", NYC's free Internet kiosks disable Web browsing". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 King, Hope (July 30, 2016). "Why free Wi-Fi kiosks in NYC can't stop people from watching porn in public". CNNMoney. CNN. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 Burns, Janet W. (September 16, 2016). "LinkNYC Drops Web Access From Kiosks After Some Users Watch Porn". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Homeless men took over New York's public WiFi to watch porn, TV and YouTube". The Independent. August 23, 2016. Archived from the original on June 14, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ↑ Puglise, Nicole (September 15, 2016). "'Bad people messed it up': misuse forces changes to New York's Wi-Fi kiosks". the Guardian. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 Hogan, Gwynne (September 22, 2017). "Greenpoint LinkNYC Kiosk Acts As 'Drug Den' Concierge: Neighbors". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Rajamani, Maya (August 30, 2016). "LinkNYC Users Watching Porn, Doing Drugs on Chelsea Sidewalks, Locals Say". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ↑ Fonrouge, Gabrielle (August 29, 2016). "Wi-Fi kiosks have become living rooms for vagrants". New York Post. Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ↑ Small, Eddie (September 1, 2016). "LinkNYC Should Have Time Limits in Wake of Porn Complaints, Official Says". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- 1 2 Marcius, Chelsia; Burke, Kerry; Fermino, Jennifer (September 15, 2016). "LinkNYC kiosks still concern for locals even without web browsing". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- 1 2 Lunden, Ingrid (October 25, 2016). "LinkNYC's free WiFi and phone kiosks hit London as LinkUK, in partnership with BT". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ McCormick, Rich (October 25, 2016). "Link brings its free public Wi-Fi booths from New York to London". The Verge. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ Sayer, Peter (October 25, 2016). "London is next in line for Google-backed gigabit Wi-Fi". PCWorld. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ Osborne, Charlie (October 31, 2016). "London's Link smart kiosks will be stripped down due to NYC complaints". ZDNet. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ Sullivan, Ben (October 27, 2016). "London's New Wi-Fi Kiosks Won't Have Public Browsing Due to NYC's Porn Problem". motherboard.vice.com. Vice. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- 1 2 Flamm, Matthew (March 17, 2016). "The Wi-Fi kiosks replacing New York pay phones will soon pop up in another city". Crain's New York Business. Archived from the original on March 29, 2017. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Department of Transportation Announces Columbus as Winner of Unprecedented $40 Million Smart City Challenge". Department of Transportation. June 23, 2016. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ Harris, Mark (July 1, 2016). "Inside Alphabet's money-spinning, terrorist-foiling, gigabit Wi-Fi kiosks". Recode. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ↑ Strunsky, Steve (July 22, 2017). "City to offer free wifi on busy sidewalks". NJ.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2017.