Ashanti Empire | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

Map of the Ashanti Empire | |||||||||||||

| Status | State union | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Kumasi | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Ashanti (Twi) (official) | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Initially Akan religion, later also Christianity | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

• 1670–1717 (first) | Osei Tutu | ||||||||||||

• 1888–1896 (13th) | Prempeh I | ||||||||||||

• 1931–1957 (last) | Prempeh II | ||||||||||||

| Osei Tutu II | |||||||||||||

| Legislature | Asante Kotoko (Council of Kumasi)[1] and the Asantemanhyiamu (National Assembly) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 1701 | ||||||||||||

• Independence from Denkyira | 1701 | ||||||||||||

• Annexed to form a British colony named Ashanti | 1901[2] | ||||||||||||

• Self-rule | 1935 | ||||||||||||

| 1957 | |||||||||||||

| Present | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| [3][4] | 259,000 km2 (100,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• [3] | 3,000,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Ghana

Ivory Coast Togo | ||||||||||||

The Asante Empire (Asante Twi: Asanteman), today commonly called the Ashanti Empire, was an Akan state that lasted from 1701 to 1901, in what is now modern-day Ghana.[6] It expanded from the Ashanti Region to include most of Ghana as well as parts of Ivory Coast and Togo.[7][8] Due to the empire's military prowess, wealth, architecture, sophisticated hierarchy and culture, the Ashanti Empire has been extensively studied and has more historic records written by European, primarily British, authors than any other indigenous culture of sub-Saharan Africa.[9][10]

Starting in the late 17th century, the Ashanti king Osei Tutu (c. 1695 – 1717) and his adviser Okomfo Anokye established the Ashanti Kingdom, with the Golden Stool of Asante as a sole unifying symbol.[6][11] Osei Tutu oversaw a massive Ashanti territorial expansion, building up the army by introducing new organisation and turning a disciplined royal and paramilitary army into an effective fighting machine.[9] In 1701, the Ashanti army conquered Denkyira, giving the Ashanti access to the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean coastal trade with Europeans, notably the Dutch.[9] The economy of the Ashanti Empire was mainly based on the trade of gold and agricultural exports[12] as well as slave trading, craft work and trade with markets further north.[5]

The army served as the effective tool to procure captives.[13] The Ashanti Empire fought several wars with neighboring kingdoms and lesser organized groups such as the Fante. The Ashanti defeated the British Empire's invasions in the first two of the four Anglo-Ashanti Wars, killing British army general Sir Charles MacCarthy and keeping his skull as a gold-rimmed drinking cup in 1824. British forces later burnt and sacked the Ashanti capital of Kumasi, however, and after the final Ashanti defeat at the fifth Anglo-Ashanti War, the Ashanti empire became part of the Gold Coast colony on 1 January 1902. Today, the Ashanti Kingdom survives as a constitutionally protected, sub-national traditional state[14] in union with the Republic of Ghana. The current king of the Ashanti Kingdom is Otumfuo Osei Tutu II Asantehene. The Ashanti Kingdom is the home to Lake Bosumtwi, Ghana's only natural lake. The state's current economic revenue is derived mainly from trading in gold bars, cocoa, kola nuts and agriculture.[15]

Etymology and origins

The name Asante means "because of war". The word derives from the Twi words ɔsa meaning "war" and nti meaning "because of". This name comes from the Asante's origin as a kingdom created to fight the Denkyira kingdom.[16]

The variant name "Ashanti" comes from British reports transcribing "Asante" as the British heard it pronounced, as-hanti. The hyphenation was subsequently dropped and the name Ashanti remained, with various spellings including Ashantee common into the early 20th century.

Between the 10th and 12th centuries AD, the ethnic Akan people migrated into the forest belt of Southern Ghana and established several Akan states: Ashanti, Brong-Ahafo, Assin-Denkyira-Fante Confederacy-Mankessim Kingdom (present-day Central region), Akyem-Akwamu-Akuapem-Kwahu (present-day Eastern region and Greater Accra), and Ahanta-Aowin-Sefwi-Wassa (present-day Western region).

Ashanti had a flourishing trade with other African states due to the Ashanti gold wealth. The Ashanti also traded enslaved people. At this time the trade of enslaved people was focused towards the north. These captives from war would go to Hausa and Mande traders and would be exchanged for goods from North Africa and other European goods.[17] [18] When the gold mines in the Sahel started to play out, the Ashanti Kingdom rose to prominence as the major player in the gold trade.[15] At the height of the Ashanti empire, the Ashanti people became wealthy through the trading of gold mined from their territory.[15]

History

Foundation

Ashanti political organization was originally centred on clans headed by a paramount chief or Omanhene.[19][6] One particular clan, the Oyoko, settled in the Ashanti's sub-tropical forest region, establishing a centre at Kumasi.[20] The Ashanti became tributaries of another Akan state, Denkyira but in the mid-17th century the Oyoko under Chief Oti Akenten started consolidating the Ashanti clans into a loose confederation against the Denkyira.[21]

The introduction of the Golden Stool (Sika dwa) was a means of centralization under Osei Tutu. According to legend, a meeting of all the clan heads of each of the Ashanti settlements was called just prior to declaring independence from Denkyira. Those included members from Nsuta, Mampong, Dwaben, Bekwai and Kokofu.[6] In this meeting the Golden Stool was commanded down from the heavens by Okomfo Anokye, chief-priest or sage advisor to Asantehene Osei Tutu I and floated down from the heavens into the lap of Osei Tutu I. Okomfo Anokye declared the stool to be symbolic of the new Ashanti Union (the Ashanti Kingdom) and allegiance was sworn to the stool and to Osei Tutu as the Asantehene. The newly declared Ashanti union subsequently waged war against and defeated Denkyira.[22] The stool remains sacred to the Ashanti as it is believed to contain the Sunsum — spirit or soul of the Ashanti people.

Independence

In the 1670s the head of the Oyoko clan, Osei Kofi Tutu I, began another rapid consolidation of Akan peoples via diplomacy and warfare.[23] King Osei Kofi Tutu I and his chief advisor, Okomfo Kwame Frimpong Anokye led a coalition of influential Ashanti city-states against their mutual oppressor, the Denkyira who held the Ashanti Kingdom in its thrall. The Ashanti Kingdom utterly defeated them at the Battle of Feyiase, proclaiming its independence in 1701. Subsequently, through hard line force of arms and savoir-faire diplomacy, the duo induced the leaders of the other Ashanti city-states to declare allegiance and adherence to Kumasi, the Ashanti capital. From the beginning, King Osei Tutu and priest Anokye followed an expansionist and an imperialistic provincial foreign policy. According to folklore, Okomfo Anokye is believed to have visited Agona-Akrofonso.[24]

Under Osei Tutu

Realizing the strengths of a loose confederation of Akan states, Osei Tutu strengthened centralization of the surrounding Akan groups and expanded the powers of the judiciary system within the centralized government. This loose confederation of small city-states grew into a kingdom and eventually an empire looking to expand its borders. Newly conquered areas had the option of joining the empire or becoming tributary states.[25] Opoku Ware I, Osei Tutu's successor, extended the borders, embracing much of Ghana's territory.[23]

European contact

European contact with the Ashanti on the Gulf of Guinea coast region of Africa began in the 15th century. This led to trade in gold, ivory, slaves, and other goods with the Portuguese.[6] On May 15, 1817, the Englishman Thomas Bowdich entered Kumasi. He remained there for several months, was impressed, and on his return to England wrote a book, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee.[26] His praise of the kingdom was disbelieved as it contradicted prevailing prejudices. Joseph Dupuis, the first British consul in Kumasi, arrived on March 23, 1820. Both Bowdich and Dupuis secured a treaty with the Asantehene, but the governor, Hope Smith, did not meet Ashanti expectations.[27]

British relations

From 1824 till 1899 there were five Anglo-Ashanti wars between the Ashanti Empire and Great Britain and its allies. The British lost or negotiated truces in several of these wars, with the final war resulting in British burning of Kumasi and official occupation of the Ashanti Empire in 1900. The wars were mainly due to Ashanti attempts to establish a stronghold over the coastal areas of present-day Ghana. Coastal peoples such as the Fante and the Ga came to rely on British protection against Ashanti incursions.

In December 1895, the British left Cape Coast with an expeditionary force to start what is known as the Third Anglo-Ashanti War, see below. The Asantehene directed the Ashanti to not resist the British advance, as he feared reprisals from Britain if the expedition turned violent. Shortly thereafter, Governor William Maxwell arrived in Kumasi as well.

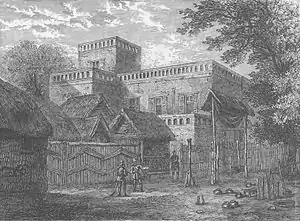

Britain annexed the territories of the Ashanti and the Fanti and constituted the Ashanti Crown Colony on 26 September 1901.[2] Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh was deposed and arrested, and he and other Ashanti leaders were sent into exile in the Seychelles. The Asante Union was dissolved. A British Resident was permanently placed in the city of Kumasi, and soon after a British fort was built there.

Uprisings of 1900 and since 1935

As a final measure of resistance, the remaining Asante court not exiled to the Seychelles mounted an offensive against the British Residents at the Kumasi Fort. The resistance was led by Asante queen Yaa Asantewaa, Queen-Mother of Ejisu. From March 28 to late September 1900, the Asante and British were engaged in what would become known as the War of the Golden Stool. In the end, the British were victorious; they exiled Asantewaa and other Asante leaders to the Seychelles to join Asante King Prempeh I.

In January 1902, Britain finally designated the Ashanti Kingdom as a protectorate. the Ashanti Kingdom was restored to self-rule on 31 January 1935. Asante King Prempeh II was restored in 1957, and the Ashanti Kingdom entered a state union with Ghana on independence from the United Kingdom.

Territorial history timeline

Government and politics

The Ashanti state was a centralized state made up of a hierarchy of heads starting from the "Abusua Panyin" who was head of a family or lineage. The family was the basic political unit in the empire. The family or lineage followed the village organization which was headed by the Odikro. All villages were then grouped together to form divisions headed by a divisional head called Ohene. The various divisions were politically grouped to form a state which was headed by an Omanhene or Amanhene. Finally, all Ashanti states formed the Ashanti Empire with the Asantehene as their king.[28]

The Ashanti government was built upon a sophisticated bureaucracy in Kumasi, with separate ministries to handle the state's affairs.[29] Of particular note was Ashanti's Foreign Office based in Kumasi; despite its small size, it allowed the state to pursue complex negotiations with foreign powers. The Office was divided into departments to handle relations separately with the British, French, Dutch, and Arabs. Scholars of Ashanti history, such as Larry Yarak and Ivor Wilks, disagree over the power of this sophisticated bureaucracy in comparison to the Asantehene, but agree that it was a sign of a highly developed government with a complex system of checks and balances.

Administration

Asantehene

At the top of Ashanti's power structure sat the Asantehene, the King of Ashanti. Each Asantahene was enthroned on the sacred Golden Stool, the Sika 'dwa, an object that came to symbolise the very power of the King. Osei Kwadwo (1764–1777) began the meritocratic system of appointing central officials according to their ability, rather than their birth.[30]

As King, the Asantehene held immense power in Ashanti, but did not enjoy absolute royal rule.[31][32] He was obliged to share considerable legislative and executive powers with Ashanti's sophisticated bureaucracy. But the Asantehene was the only person in Ashanti permitted to invoke the death sentence in cases of crime. During wartime, the King acted as Supreme Commander of the Ashanti army, although during the 19th century, the fighting was increasingly handled by the Ministry of War in Kumasi. Each member of the confederacy was also obliged to send annual tribute to Kumasi.

The Asantehene (King of all Ashanti) reigned over all and was King of the division of Kumasi, the nation's capital, and the Ashanti Empire. He was elected in the same manner as all other chiefs. In this hierarchical structure, every chief or King swore fealty to the one above him—from village and subdivision, to division, to the chief of Kumasi, and finally the Asantehene swore fealty to the State.[6]

The elders circumscribed the power of the Asantehene, and the chiefs of other divisions considerably checked the power of the King. This in practical effect created a system of checks and balances. As the symbol of the nation, the Asantehene received significant deference ritually, for the context was religious in that he was a symbol of the people in the flesh: the living, dead or yet to be born. When the king committed an act not approved of by the counsel of elders or the people, he could possibly be impeached, and demoted to a commoner.

The existence of aristocratic organizations and the council of elders is evidence of an oligarchic tendency in Ashanti political life. Though older men tended to monopolize political power, Ashanti instituted an organization of young men, the nmerante, that tended to democratize and liberalize the political process in the empire. The council of elders undertook actions only after consulting a representative of the nmerante. Their views were taken seriously as they participated in decision-making in the empire.

Residence

The current residence of the Asantehene is the Manhyia Palace built in 1925 by the British and presented to the Prempeh I as a present upon his return from exile. The original palace of the Asantehene in Kumasi was burned down by the British in 1874. From European accounts, the edifice was massive and ornately built. In 1819, English traveler and author, Thomas Edward Bowdich described the palace complex as[33]

...an immense building of a variety of oblong courts and regular squares [with] entablatures exuberantly adorned with bold fan and trellis work of Egyptian character. They have a suite of rooms over them, with small windows of wooden lattice, of intricate but regular carved work, and some have frames cased with thin gold. The squares have a large apartment on each side, open in front, with two supporting pillars, which break the view and give it all the appearance of the proscenium or front of the stage of the older Italian theaters. They are lofty and regular, and the cornices of a very bold cane-work in alto-relievo. A drop-curtain of curiously plaited cane is suspended in front, and in each, we observed chairs and stools embossed with gold, and beds of silk, with scattered regalia.[34]

Winwood Reade also described his visit to the Ashanti Royal Palace of Kumasi in 1874: "We went to the king's palace, which consists of many courtyards, each surrounded with alcoves and verandahs, and having two gates or doors, so that each yard was a thoroughfare . . . But the part of the palace fronting the street was a stone house, Moorish in its style . . . with a flat roof and a parapet, and suites of apartments on the first floor. It was built by Fanti masons many years ago. The rooms upstairs remind me of Wardour Street. Each was a perfect Old Curiosity Shop. Books in many languages, Bohemian glass, clocks, silver plate, old furniture, Persian rugs, Kidderminster carpets, pictures and engravings, numberless chests and coffers. A sword bearing the inscription From Queen Victoria to the King of Ashantee. A copy of the Times, 17 October 1843. With these were many specimens of Moorish and Ashanti handicraft."[35]

_p338_PLATE_5_-_COOMASSIE%252C_ODUMATA'S_SLEEPING_ROOM.jpg.webp) Odumata's Sleeping Room (1819).

Odumata's Sleeping Room (1819)._p341_PLATE_7_-_COOMASSIE%252C_PART_OF_A_PIAZZA_IN_THE_PALACE.jpg.webp) Piazza in the Palace (1819).

Piazza in the Palace (1819)._p344_PLATE_9_-_COOMASSIE%252C_PART_OF_ADAM_STREET.jpg.webp) Adum Street (1819).

Adum Street (1819).

Asanteman council

This institution assisted the Asantehene and served as an advisory body to the king. The council was made up of Amanhene or paramount chiefs who were leaders of the various Ashanti states. The council also included other provincial chiefs. By law the Asantehene never ignored the decisions of the Asanteman council. Doing so could get him de-stooled from the throne.[36][28]

Amanhene

The Ashanti Empire was made up of metropolitan and provincial states. The metropolitan states were made up of Ashanti citizens known as amanfo. The provincial states were other kingdoms absorbed into the empire. Every metropolitan Ashanti state was headed by the Amanhene or paramount chief. Each of these paramount chiefs served as principal rulers of their own states, where they exerted executive, legislative and judicial powers.[36]

Ohene

The Ohene were divisional chiefs under the Amanhene. Their major function was to advise the Amanhene. The divisional chiefs were the highest order in various Ashanti state divisions. The divisions were made up of various villages put together. Examples of divisional chiefs included Krontihene, Nifahene, Benkumhene, Adontenhene and Kyidomhene.[36]

Odikuro

Each village in Asante had a chief called Odikro who was the owner of the village. The Odikro was responsible for the maintenance of law and order. He also served as a medium between the people of his jurisdiction, the ancestor and the gods. As the head of the village, the Odikro presided over the village council.[36][28]

Queen

.jpg.webp)

The queen or Ohenemaa was an important figure in Ashanti political systems. She was the most powerful female in the Empire. She had the prerogative of being consulted in the process of installing a chief or the king, as she played a major role in the nomination and selection. She settled disputes involving women and was involved in decision-making alongside the Council of elders and chiefs.[36] Not only did she participate in the judicial and legislative processes, but also in the making and unmaking of war, and the distribution of land.[37]

Obirempon

Successful entrepreneurs who accumulated large wealth and men as well as distinguished themselves through heroic deeds were awarded social and political recognition by being called "Abirempon" or "Obirempon" which means big men. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries AD, the appellation "Abirempon" had formalized and politicized to embrace those who conducted trade from which the whole state benefited. The state rewarded entrepreneurs who attained such accomplishments with Mena (elephant tail) which was the "heraldic badge" [38] Obirempons had a fair amount of legislative power in their regions, more than the local nobles of Dahomey but less than the regional governors of the Oyo Empire. In addition to handling the region's administrative and economic matters, the obirempon also acted as the Supreme Judge of their jurisdiction, presiding over court cases.

Kotoko council

The Kotoko was a government council in the Ashanti government. Politically, the kotoko council served as the counterweight to the king's council of elders and basically embodied the aristocratic party in the government. The council formed the Legislature of Ashanti governmental system.[1] It was made up of the Asantehene, the Queen mother as well as the state chiefs and their ministers.

Elections

The election of Kings and the Asantehene (King of Kings or emperor ) himself followed a pattern. The senior female of the kingly lineage nominated the eligible males. This senior female then consulted the elders, male and female, of that line. The final candidate is then selected. That nomination was sent to a council of elders, who represented other lineages in the town or district.

The Elders then presented the nomination to the assembled people. If the assembled citizens disapproved of the nominee, the process was restarted.[39] Chosen, the new Kings were enstooled by the Elders, who admonished him with expectations. The chosen Kings swore a solemn oath to the Earth Goddess and to his ancestors to fulfill his duties honorably in which he "sacrificed" himself and his life for the betterment of the state.

This elected and enstooled King enjoyed a great majestic ceremony with much spectacle and celebration. He reigned with much despotic power, including the ability to make judgments of life and death on his subjects. However, he did not enjoy absolute rule. Upon the stool, the King was sacred. He served as the holy intermediary between the people and the ancestors. His powers theoretically were more apparent than real and hinged on his attention to the advice and decisions of the Council of Elders.

Impeachment

Kings of the Ashanti Empire who violated any of the oaths taken during his or her enstoolment, were destooled by Kingmakers.[40] For instance, if a king punished citizens arbitrarily or was exposed as corrupt, he would be destooled. Destoolment entailed kingmakers removing the sandals of the king and bumping his buttocks on the ground three times. Once destooled from office, his sanctity and thus reverence were lost, as he could not exercise any of the powers he had as king; this includes Chief administrator, Judge, and Military Commander. The now previous king was dispossessed of the Stool, swords and other regalia which symbolized his office and authority. He also lost his position as custodian of the land. However, even if destooled from office, the king remained a member of the royal family from which he was elected.[40] An impeachment occurred during the reign of Kusi Obodom, caused by a failed invasion of Dahomey.[41]

Legal system

Okomfo Anokye was responsible for creating the Seventy-Seven Laws of Komfo Anokye which served as the codified constitution of the Ashanti Empire.[44][45][46]

The Ashanti state, in effect, was a theocracy. It invokes religious, rather than secular-legal postulates. What the modern state views as crimes, Ashanti view practically as sins. Antisocial acts disrespect the ancestors, and are only secondarily harmful to the community. If the chief or King fails to punish such acts, he invokes the anger of the ancestors and the gods, and is therefore in danger of impeachment. The penalty for some crimes (sins) is death, but this is seldom imposed; a more common penalty is banishment or imprisonment. The King typically exacts or commutes all capital cases. These commuted sentences by King and chiefs sometimes occur by ransom or bribe; they are regulated in such a way that they should not be mistaken for fines, but are considered as revenue to the state, which for the most part welcomes quarrels and litigation. Commutations tend to be far more frequent than executions.

Ashanti are repulsed by murder, and suicide is considered murder. They decapitate those who commit suicide, the conventional punishment for murder. The suicide thus had contempt for the court, for only the King may kill an Ashanti.

In a murder trial, intent must be established. If the homicide is accidental, the murderer pays compensation to the lineage of the deceased. The insane cannot be executed because of the absence of responsible intent – except for murder or cursing the King; in the case of cursing the king, drunkenness is a valid defense. Capital crimes include murder, incest within the female or male line, and intercourse with a menstruating woman, rape of a married woman, and adultery with any of the wives of a chief or the King. Assaults or insults of a chief or the court or the King also carried capital punishment.

Cursing the King, calling down powers to harm the King, is considered an unspeakable act and carries the weight of death. One who invokes another to commit such an act must pay a heavy indemnity. Practitioners of harmful (evil) forms of sorcery and witchcraft receive death but not by decapitation, for their blood must not be shed. They receive execution by strangling, burning, or drowning.

Ordinarily, families or lineages settle disputes between individuals. Nevertheless, such disputes can be brought to trial before a chief by uttering the taboo oath of a chief or the King. In the end, the King's Court is the sentencing court, for only the King can order the death penalty. Before the Council of Elders and the King's Court, the litigants orate comprehensively. Anyone present can cross-examine the defendant or the accuser, and if the proceedings do not lead to a verdict, a special witness is called to provide additional testimony. If there is only one witness, their sworn oath assures the truth is told. Moreover, that he favours or is hostile to either litigant is unthinkable. Cases with no witness, like sorcery or adultery are settled by ordeals, like drinking poison.

Ancestor Veneration establishes the Ashanti moral system, and it provides the principal foundation for governmental sanctions. The link between mother and child centres the entire network, which includes ancestors and fellow men as well. Its judicial system emphasizes the Ashanti conception of rectitude and good behaviour, which favours harmony among the people. The rules were made by Nyame (Supreme God) and the ancestors, and one must behave accordingly.

Geography

The Ashanti Empire was one of a series of states along the coast including Dahomey, Benin, and Oyo. The Ashanti had mountains and large agricultural surpluses.[3] The southern part of the Ashanti Empire was covered with moist semi-deciduous forest whilst the Guinea savanna covered the northern part of the state. The Guinea Savanna consists of short deciduous and fire resistant trees. Riparian forests also occur along the Afram River and streams of the savanna zone. Soils in Ashanti were mainly of two types; forest ochrosols in the southern part of Ashanti whilst the savanna ochrosols were confined to northern part of the empire.[3]

The predominant fauna or food rich wildlife and animal species encountered in the Ashanti Empire were the hen, sheep, goat, duck, turkey, rabbit, guinea fowl, fish, and the porcupine which became the national emblem of the state, as well as about thirty multipurpose flora species of trees and shrubs and over thirty-five ornamental plants which beautified the environs of Ashanti. These tree/shrub-crop-animal (hen/fish) components were intensively integrated spatially and/or sequentially on the same land unit of individual Ashanti houses.[3]

Between 1700 and 1715, Osei Tutu I conquered the neighboring states of Twifo, Wassa and Aowin. Opoku Ware I who succeeded Osei Tutu, led the integration of Akan states such as Tekyiman, Akyem and Kwahu into Ashanti after embarking on wars of conquest between 1720 and 1750. After the conquest of the Akyem in 1742, the Ashanti exerted power unto the coast. From 1730 to 1770, the Ashanti Empire expanded north into the Savannah states of Gonja, Dagbon and Krakye.[47] By 1816, the Ashanti had absorbed coastal states such as the Fante Confederacy.[48][49] The expansion into Dagbon is refuted by some researchers such as A.A. Lliasu. Scholar Karl J. Haas argues that "claims of Asante dominance over Dagbon in the precolonial era have been greatly exagged."[50]

Economy

Resources

The lands within the Ashanti Kingdom were also rich in river-gold, cocoa and kola nuts, and the Ashanti were soon trading with the Portuguese at coastal fort Sao Jorge da Mina, later Elmina,and with the Hausa states.[6]

Agriculture

The Ashanti prepared the fields by burning before the onset of the rainy season and cultivated with an iron hoe. Fields are left fallow for a couple years, usually after two to four years of cultivation. Plants cultivated include plantains, yams, manioc, corn, sweet potatoes, millet, beans, onions, peanuts, tomatoes, and many fruits. Manioc and corn are New World transplants introduced during the Atlantic European trade. Many of these vegetable crops could be harvested twice a year and the cassava (manioc), after a two-year growth, provides a starchy root.[51][52]

The Ashanti transformed palm wine, maize and millet into beer, a favourite drink; and made use of the oil from palm for many culinary and domestic uses.[51][52]

Communication

The Ashanti invented the Fontomfrom, an Asante talking drum, and they also invented the Akan Drum. They drummed messages to distances of over 300 kilometres (200 mi), as rapidly as a telegraph. Asante dialect (Twi) and Akan, the language of the Ashanti people is tonal and more meaning is generated by tone. The drums reproduced these tones, punctuations, and the accents of a phrase so that the cultivated ear heard the entirety of the phrase itself.

The Ashanti readily heard and understood the phrases produced by these "talking drums". Standard phrases called for meetings of the chiefs or to arms, warned of danger, and broadcast announcements of the death of important figures. Some drums were used for proverbs and ceremonial presentations.

Although pre-literate, the Ashanti recruited literate individuals into its government to increase the efficiency of the state's diplomacy. Some written records were also kept.[53][54] Historian Adjaye, gives estimates based on surviving letters by the Ashanti that documents from the Ashanti government "could have exceeded several thousands."[54] Writing was also used in record keeping during court proceedings. Bowdich documented in the early nineteenth century about the "trial of Apea Nyano" on 8 July 1817 where he states that "the Moorish secretaries were there to take notes of the transactions of the day." Wilks adds that such transcripts have not survived today.[55]

Before the 19th century, couriers were trained to memorize the exact contents of the verbal message and by the 19th century, the Ashanti government relied on writing for diplomacy. In the 1810s, it was common for couriers to be deployed with despatch boxes.[56] For Wilks, evidence exists on the use of mounted couriers during the reign of Kwaku Dua I around the Metropolitan districts. He cites a case In 1841 when Freeman documented the arrival of a party of messengers sent by the Asantehene to Kaase. The chief of these messengers "rode on a strong Ashanti pony, with an Arabic or Moorish saddle and bridle." Wilks argues the tsetse fly nullified the extensive use of horses to speed communications.[57]

Demography

The population history of the Ashanti Kingdom was one of slow centralization. In the early 19th century the Asantehene used the annual tribute to set up a permanent standing army armed with rifles, which allowed much closer control of the Ashanti Kingdom. The Ashanti Kingdom was one of the most centralised states in sub-Saharan Africa. Osei Tutu and his successors oversaw a policy of political and cultural unification and the union had reached its full extent by 1750. It remained an alliance of several large city-states which acknowledged the sovereignty of the ruler of Kumasi and the Ashanti Kingdom, known as the Asantehene. The Ashanti Kingdom had dense populations, allowing the creation of substantial urban centres.[3] The Ashanti controlled over 250,000 square kilometers while ruling approximately 3 million people.[3]

Architecture

The Ashanti traditional buildings are the only remnants of Ashanti architecture. Construction and design consisted of a timber framework filled up with clay and thatched with sheaves of leaves. The surviving designated sites are shrines, but there have been many other buildings in the past with the same architectural style.[58] These buildings served as palaces and shrines as well as houses for the affluent.[59] The Ashanti Empire also built mausoleums which housed the tombs of several Ashanti leaders. Generally, houses whether designed for human habitation or for the deities, consisted of four separate rectangular single-room buildings set around an open courtyard; the inner corners of adjacent buildings were linked by means of splayed screen walls, whose sides and angles could be adapted to allow for any inaccuracy in the initial layout. Typically, three of the buildings were completely open to the courtyard, while the fourth was partially enclosed, either by the door and windows, or by open-work screens flanking an opening.[60]

Infrastructure

Infrastructure such as road transport and communication throughout the empire was maintained via a network of well-kept roads from the Ashanti mainland to the Niger river and other trade cities.[51][52] English visitors to Kumasi in the 19th century, noted the division of the capital into 77 wards with 27 main streets; one of which was 100 yards wide. Many houses especially those near the king's palace were two story buildings embodied with indoor plumbing in the form of toilets that were flushed with gallons of boiling water.[61] Bowdich revealed in his 1817 account that all streets of Kumasi were named.[62][63] Stationed at various points of Ashanti roads were the Nkwansrafo or road wardens who served as the highway police; checking the movement of traders and strangers on all roads. They were also responsible for scouting and were charged with the collection of tolls from traders.[64]

In the early 19th century larger rivers were either forded in the dry season or crossed by canoe or line-and-raft ferries. Smaller rivers were either waded, or were bridged by a tree trunk: in both cases a rope handrail was usually stretched across the river to assist the traveller. However, by 1841, in response to European influences, the Ashanti Empire began to build bridges across water bodies for transport.[65] Asantehene Kwaku Dua ordered proper bridges to be built across streams in the metropolitan area of Kumase. Thomas Freeman, who visited the empire in 1841, described the construction as:

Some stout, forked sticks or posts are driven in the centre of the stream at convenient distances, across which are placed some strong beams, fastened to the posts with withes, from the numerous climbing plants on every hand. On these bearers are placed long stout poles which are covered with earth from fourth to six inches thick....

— Freeman.[66]

Police and military

Police

The Asantehene inherited his position from his queen mother, and he was assisted at the capital, Kumasi, by a civil service of men talented in trade, diplomacy, and the military, with a head called the Gyaasehene.[51] Men from the Arabian Peninsula, Sudan, and Europe were employed in the Ashanti empire civil service; all of whom were appointed by the Asantehene.[51] In the metropolitan areas of Ashanti, several police forces were responsible for maintaining law and order. In Kumasi, a uniformed police, who were distinguished by their long hair, maintained order by ensuring no one else entered and left the city without permission from the government.[67] The ankobia or special police were used as the empire's special forces and bodyguards to the Asantehene, as sources of intelligence, and to suppress rebellion.[51] For most of the 19th century and into the 20th century, the Ashanti sovereign state remained powerful.[68]

Military

The Ashanti armies served the empire well, supporting its long period of expansion and subsequent resistance to European colonization.

Armament was primarily with firearms, but some historians hold that indigenous organization and leadership probably played a more crucial role in Ashanti successes.[69] These are, perhaps, more significant when considering that the Ashanti had numerous troops from conquered or incorporated peoples, and faced a number of revolts and rebellions from these peoples over its long history. The political genius of the symbolic "golden stool" and the fusing effect of a national army however, provided the unity needed to keep the empire viable. Total potential strength was some 80,000 to 200,000, making the Ashanti army bigger than the well known Zulu, and comparable to possibly Africa's largest – the legions of Ethiopia.[70] The Ashanti army was described as a fiercely organized one whose king could "bring 200,000 men into the field and whose warriors were evidently not cowed by Snider rifles and 7-pounder guns"[71]

While actual forces deployed in the field were less than potential strength, tens of thousands of soldiers were usually available to serve the needs of the empire. Mobilization depended on small cadres of regulars, who guided and directed levees and contingents called up from provincial governors.

Organization was structured around an advance guard, main body, rear guard and two right and left wing flanking elements. This provided flexibility in the forest country the Ashanti armies typically operated in. Horses were known to survive in Kumasi but because they could not survive in the tsetse fly-infested forest zone in the south, there was no cavalry. Ashanti high-ranking officers rode horses with the hauteur of European officers but they did not ride to battle.[72] The approach to the battlefield was typically via converging columns, and tactics included ambushes and extensive maneuvers on the wings. Unique among African armies, the Ashanti deployed medical units to support their fighters. This force was to expand the empire substantially and continually for over a century, and defeated the British in several encounters.[70]

Brass barrel blunderbuss were produced in some states in the Gold Coast including the Ashanti Empire around the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Various accounts indicate that Asante blacksmiths were not only able to repair firearms, but that barrels, locks and stocks were on occasion remade.[73]

Wars of the Asante

From 1806 until 1896, the Ashanti state was in a perpetual state of war involving expansion or defense of its domain. Ashanti exploits against other African forces made it the paramount power in the region. Its impressive performance against the British also earned it the respect of European powers.

Asante–Fante War

In 1806, the Ashanti pursued two rebel leaders through Fante territory to the coast. The British refusal to surrender the rebels led to an Ashanti attack. This was devastating enough that the British handed over a rebel; the other escaped.[74] In 1807 disputes with the Fante led to the Ashanti–Fante War, in which the Ashanti were victorious under Asantehene Osei Bonsu ("Bonsu, the whale").

Ga–Fante War

In the 1811 Ga–Fante War, a coalition of Asante and Ga fought against an alliance of Fante, Akwapim and Akim states. The Asante war machine was successful in defeating the alliance in open combat pushing their enemies towards the Akwapim hills. Ashanti however abandoned their campaign of pursuit after capturing a British fort and establishing their presence and authority on the coast.

Ashanti–Akim–Akwapim War

In 1814 the Ashanti launched an invasion of the Gold Coast, largely to gain access to European traders. In the Ashanti–Akim–Akwapim War, the empire faced the Akim–Akwapim alliance. After several battles, the out numbered Akim–Akwapim alliance were defeated and became tributories to the Ashantis. The Ashanti was established from the midlands down to the coast.

Anglo-Ashanti Wars

First Anglo-Ashanti War

The first of the Anglo-Ashanti wars occurred in 1823. In these conflicts, the Ashanti empire faced off, with varying degrees of success, against the British Empire residing on the coast. The root of the conflict traces back to 1823 when Sir Charles MacCarthy, resisting all overtures by the Ashanti to negotiate, led an invading force. The Ashanti defeated this, killed MacCarthy, took his head for a trophy and swept on to the coast. However, disease forced them back. The Ashanti were so successful in subsequent fighting that in 1826 they again moved on the coast. The Ashanti were stopped about 15 kilometres (10 mi) north of Accra by a British led force. They fought against superior numbers of British allied forces, including Denkyirans until the novelty of British rockets caused the Ashanti army to flee.[75] In 1831, a treaty led to 30 years of peace, with the Pra River accepted as the border.

Second Anglo-Ashanti War

With the exception of a few Ashanti light skirmishes across the Pra in 1853 and 1854, the peace between the Ashanti and British Empire had remained unbroken for over 30 years. Then, in 1863, a large Ashanti delegation crossed the river pursuing a fugitive, Kwesi Gyana. There was fighting, casualties on both sides, but the governor's request for troops from England was declined and sickness forced the withdrawal of his West Indian troops. The war ended in 1864 as a stalemate with both sides losing more men to sickness than any other factor.

Third Anglo-Ashanti War

In 1869 a European missionary family was taken to Kumasi. They were hospitably welcomed and were used as an excuse for war in 1873. Also, Britain took control of Ashanti land claimed by the Dutch. The Ashanti invaded the new British protectorate. General Wolseley and his famous Wolseley ring were sent against the Ashanti. This was a modern war, replete with press coverage (including by the renowned reporter Henry Morton Stanley) and printed precise military and medical instructions to the troops.[77] The British government refused appeals to interfere with British armaments manufacturers who were unrestrained in selling to both sides.[78]

All Ashanti attempts at negotiations were disregarded. Wolseley took 2,500 British troops and several thousand West Indian and African troops to Kumasi. It arrived in Kumasi in January 1896 along a route cleared by an advance contingent under the command of Robert Baden-Powell.[79][80] The capital was briefly occupied. The British were impressed by the size of the palace and the scope of its contents, including "rows of books in many languages."[81] The Ashanti had abandoned the capital after a bloody war. The British burned it.[82]

The British and their allies suffered considerable casualties in the war losing numerous soldiers and high ranking army officers.[83] but in the end the firepower was too much to overcome for the Ashanti. The Asantehene (the king of the Ashanti) signed a British treaty in July 1874 to end the war.

Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War

In 1895, the Ashanti turned down an unofficial offer to become a British protectorate.

The Ashanti wanting to keep French and European colonial forces out of the territory (and its gold), the British were anxious to conquer the Ashanti once and for all. Despite being in talks with the state about making it a British protectorate, Britain began the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War in 1895 on the pretext of failure to pay the fines levied on the Ashanti monarch after the 1874 war. The British were victorious and the Ashanti was forced to sign a treaty.

Culture and society

Family

Standing among families was largely political. The royal family typically topped the hierarchy, followed by the families of the chiefs of territorial divisions. In each chiefdom, a particular female line provides the chief. A committee of several men eligible for the post elects the chief. The typical Ashanti family was extended and matrilineal.[84] A mother's brother was the legal guardian of her children. The father on the other hand had fewer legal responsibilities for his children with the exception of ensuring their well-being. Women also had the right to initiate divorce whiles the husband had some legal rights over his wife such as the right to cut off her nose for adultery.[85]

Clothing

Prominent people wore silk. The ordinary Ashanti wore cotton whiles slaves dressed in black cloth. Garments signalled the rank of the wearer in society and its colour expressed different meanings. White was worn by ordinary people after winning a court case. Dark colours were worn for funerals or mourning.[86] Laws existed to restrict certain Kente designs to the nobility. Some cotton or silk patterns on the Kente were designed solely for the king and could only be worn with his permission.[86]

Education and children

Education in the Ashanti Kingdom was conducted by Asante and imported scholars and Ashanti people would often attend schools in Europe for their higher education.

Tolerant parents are typical among the Ashanti. Childhood is considered a happy time and children cannot be responsible for their actions. The child is not responsible for their actions until after puberty. A child is harmless and there is no worry for the control of their soul, the original purpose of all funeral rites, so the ritual funerals typically given to the deceased Ashanti are not as lavish for the children.

The Ashanti adored twins when they were born within the royal family because they were seen as a sign of impending fortune. Ordinarily, boy twins joined the army and twin girls potential wives of the King. If the twins are a boy and girl, no particular career awaits them. Women who bear triplets are greatly honored because three is regarded as a lucky number. Special rituals ensue for the third, sixth, and ninth child. The fifth child (unlucky five) can expect misfortune. Families with many children are well respected and barren women scoffed at.

Adinkra Symbols

The Ashanti used Adinkra symbols in their daily society. The symbols were used as a form of decoration, logos, arts, sculpture and pottery.

Menstruation and impurity

The Ashanti held puberty rites only for females. Fathers instruct their sons without public observance. The privacy of boys was respected in the Ashanti kingdom. As menstruation approaches, a girl goes to her mother's house. When the girl's menstruation is disclosed, the mother announces the good news in the village beating an iron hoe with a stone. Old women come out and sing Bara (menstrual) songs.

Menstruating women suffered numerous restrictions. The Ashanti viewed them as ritually unclean. They did not cook for men, nor did they eat any food cooked for a man. If a menstruating woman entered the ancestral stool (shrine) house, she was arrested, and the punishment could result in death. If this punishment is not exacted, the Ashanti believe, the ghost of the ancestors would strangle the chief. Menstruating women lived in special houses during their periods as they were forbidden to cross the threshold of men's houses. They swore no oaths and no oaths were sworn for or against them. They did not participate in any of the ceremonial observances and did not visit any sacred places.

Healthcare and death

Sickness and death were major events in the kingdom. The ordinary herbalist divined the supernatural cause of the illness and treated it with herbal medicines.

People loathed being alone for long without someone available to perform this rite before the sick collapsed. The family dressed the deceased in their best clothes, and adorned them with packets of gold dust (money for the after-life), ornaments, and food for the journey "up the hill". The body was normally buried within 24 hours. Until that time the funeral party engage in dancing, drumming, shooting of guns, all accompanied by the wailing of relatives. This was done because the Ashanti typically believed that death was not something to be sad about, but rather a part of life. As the Ashanti believed in an after-life, families felt they would be reunited with their ancestors upon death. Funeral rites for the death of a king involved the whole kingdom and were a much more elaborate affair.

Ceremony

The greatest and most frequent ceremonies of the Ashanti recalled the spirits of departed rulers with an offering of food and drink, asking their favour for the common good, called the Adae. The day before the Adae, Akan drums broadcast the approaching ceremonies. The stool treasurer gathers sheep and liquor that will be offered. The chief priest officiates the Adae in the stool house where the ancestors came. The priest offers each food and a beverage. The public ceremony occurs outdoors, where all the people joined the dancing. Minstrels chant ritual phrases; the talking drums extol the chief and the ancestors in traditional phrases. The Odwera, the other large ceremony, occurs in September and typically lasted for a week or two. It is a time of cleansing of sin from society the defilement, and for the purification of shrines of ancestors and the gods. After the sacrifice and feast of a black hen—of which both the living and the dead share—a new year begins in which all are clean, strong, and healthy.

Slavery

Slavery was historically a tradition in the Ashanti Empire, with slaves typically taken as captives from enemies in warfare. The Ashanti Empire was the largest slaveowning and slave trading state in the territory of today's Ghana during the Atlantic slave trade.[87] The welfare of their slaves varied from being able to acquire wealth and intermarry with the master's family to being sacrificed in funeral ceremonies. The Ashanti believed that slaves would follow their masters into the afterlife. Slaves could sometimes own other slaves, and could also request a new master if the slave believed he or she was being severely mistreated.[88][89]

The modern-day Ashanti claim that slaves were seldom abused,[90] and that a person who abused a slave was held in high contempt by society. They defend the "humanity" of Ashanti slavery by noting that those slaves were allowed to marry.[24] If a master found a female slave desirable, he might marry her. He preferred such an arrangement to that of a free woman in a conventional marriage, because marriage to an enslaved woman allowed the children to inherit some of the father's property and status[91] This favoured arrangement occurred primarily because of what some men considered their conflict with the matrilineal system. Under this kinship system, children were considered born into the mother's clan and took their status from her family. Generally her eldest brother served as mentor to her children, particularly for the boys. She was protected by her family. Some Ashanti men felt more comfortable taking a slave girl or pawn wife in marriage, as she would have no abusua (older male grandfather, father, uncle or brother) to intercede on her behalf when the couple argued. With an enslaved wife, the master and husband had total control of their children, as she had no kin in the community.

In popular culture

The Ashanti Empire has been depicted in a number of different works of nonfiction, detailing the structure of the empire

Literature and theatre

- The novel The Two Hearts of Kwasi Boachi(1997)[92] is based on the memoirs of Kwasi Boachi, the son of the Asantehene Kwaku Dua I, from when he and his cousin Kwame Poku were sent to the Netherlands in 1837 to receive a European education.

- It was later adapted into an opera in 2007 by the author Arthur Japin and composer Jonathan Dove[93]

- The 2006 novel Copper Sun's protagonist Amari comes from the Ashanti Empire.

Literature

Television

- The Ashanti Empire is referenced in the Static Shock episodes "Static in Africa" and "Out of Africa", where Static and his family visit Ghana.

Video games

The Ashanti Empire has been depicted in some historical war strategy video games, along with being characters in video games with origins from the area

- In the grand strategy video games Europa Universalis IV (2013) and Victoria 3 (2022), both developed by Paradox Interactive, the Ashanti Empire appears as one of many historical nations that players can play as or interact with.

- In Crusader Kings III, the Ashanti Empire is one of the many nations that players can play or interact as.

- In Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag, two characters, Kumi Berko, a pirate playable in the multiplayer mode under the pseudonym "The Mercenary", and Antó, a Master Assassin of the West Indies Brotherhood, were both born in the Ashanti Empire.

- The Ashanti Empire appears as a playable minor civilization in Age of Empires III.

See also

References

- 1 2 Edgerton, Robert B. Fall of the Asante Empire: The Hundred Year War for Africa's Gold Coast. Free Press, 1995.

- 1 2 Ashanti Order in Council 1901.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Obeng, J. Pashington (1996). Asante Catholicism: Religious and Cultural Reproduction Among the Akan of Ghana. BRILL. p. 20. ISBN 978-90-04-10631-4.

An empire of a hundred thousand square miles, occupied by about three million people from different ethnic groups, made it imperative for the Asante to evolve sophisticated statal and parastatal institutions [...]

- ↑ Iliffe, John (1995). Africans: The History of a Continent. Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9780521484220.

- 1 2 Arhin, Kwame (1990). "Trade, Accumulation and the State in Asante in the Nineteenth Century". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 60 (4): 524–537. doi:10.2307/1160206. JSTOR 1160206. S2CID 145522016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Osei Tutu | king of Asante empire". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ↑ Davidson, Basil (2014-10-29). West Africa before the Colonial Era: A History to 1850. Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-317-88265-7.

- ↑ Isichei, Elizabeth (1997). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 346. ISBN 9780521455992.

- 1 2 3 Collins and Burns (2007), p. 140.

- ↑ McCaskie (2003), p. 2.

- ↑ "Asante Kingdom". Irie Magazine. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ↑ Green, Toby (31 January 2019). A fistful of shells : West Africa from the rise of the slave trade to the age of revolution (Kindle-Version ed.). London: Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 108, 247. ISBN 978-0-241-00328-2.

- ↑ Shumway, Rebecca. The Fante and the transatlantic slave trade. Rochester, NY. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-78204-572-4.

- ↑ Roeder, Philip (2007). Where Nation-States Come From: Institutional Change in the Age of Nationalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-0691134673.

- 1 2 3 Collins and Burns (2007), p. 139.

- ↑ "Asante – The People Of A Wealthy Gold-Rich Empire – BlackFaces". Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ↑ , BlackPast.

- ↑ , PBS.

- ↑ Kings And Queens Of Asante Archived 2012-10-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ashanti.com.au Archived 2012-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Ghana - THE PRECOLONIAL PERIOD". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ↑ Alan Lloyd, The Drums of Kumasi, London: Panther, 1964, pp. 21–24.

- 1 2 Shillington, Kevin, History of Africa, New York: St. Martin's, 1995 (1989), p. 194.

- 1 2 History of the Ashanti Empire. Archived 2012-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Gilbert, Erik, Africa in World History: From Prehistory to the Present, 2004.

- ↑ Bowdich, Thomas Edward (2019). Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee, with a statistical account of that kingdom, and geographical notices of other parts of the interior of Africa. London: J. Murray. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 28–38.

- 1 2 3 Gadzekpo (2005), p. 91–92.

- ↑ Chioma, Unini (2020-03-15). "Historical Reminisciences: Great Empires Of Yore (Part 15) By Mike Ozekhome, SAN". TheNigeriaLawyer. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- ↑ Shillington, p. 195.

- ↑ Tordoff, William (November 1962). "The Ashanti Confederacy1". The Journal of African History. 3 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1017/S0021853700003327. ISSN 1469-5138. S2CID 159479224.

- ↑ Aidoo, Agnes A. (1977). "Order and Conflict in the Asante Empire: A Study in Interest Group Relations". African Studies Review. 20 (1): 1–36. doi:10.2307/523860. ISSN 0002-0206. JSTOR 523860. S2CID 143436033.

- 1 2 Prussin, Labelle (1980). "Traditional Asante Architecture". African Arts. 13 (2): 57–65+78–82+85–87. doi:10.2307/3335517. JSTOR 3335517. S2CID 191603652.

- ↑ The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal. 1819. p. 291.

- ↑ Wilks 1989, p. 201

- 1 2 3 4 5 Prince A. Kuffour (2015). Concise Notes on African and Ghanaian History. K4 Series Investment Ventures. pp. 205–206. ISBN 9789988159306. Retrieved 2020-12-16 – via Books.google.com.

- ↑ Arhin, Kwame, "The Political and Military Roles of Akan Women", in Christine Oppong (ed.), Female and Male in West Africa, London: Allen and Unwin, 1983.

- ↑ Obeng, J.Pashington (1996). Asante Catholicism; Religious and Cultural Reproduction among the Akan of Ghana. Vol. 1. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10631-4.

- ↑ Apter David E. (2015). Ghana in Transition. Princeton University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9781400867028.

- 1 2 Obeng, J.Pashington (1996). Asante Catholicism; Religious and Cultural Reproduction among the Akan of Ghana. Vol. 1. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10631-4.

- ↑ Pescheux 2003, p. 449.

- 1 2 Wilks (1989), p. 206.

- ↑ Wilks (1989), p. 377.

- ↑ McCaskie, T. C. (1986). "Komfo Anokye of Asante: Meaning, History and Philosophy in an African Society". The Journal of African History. 27 (2): 315–339. doi:10.1017/S0021853700036690. JSTOR 181138. S2CID 145530470.

- ↑ Claessen, Henri J.M.; Oosten, Jarich Gerlof (1996). Ideology and the Formation of Early States. Brill. p. 89. ISBN 9789027979049.

- ↑ Eisenstadt, Shmuel Noah.; Abitbol, Michael; Chazan, Naomi (1988). The Early State in African Perspective: Culture, Power, and Division of Labor. Brill. p. 68. ISBN 9004083553.

- ↑ Gocking (2005), p. 21-23.

- ↑ Agbodeka, Francis (1964). "The Fanti Confederacy 1865–69: An Enquiry Into the Origins, Nature and Extent of an Early West African Protest Movement". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. Accra, Ghana: Historical Society of Ghana. 7: 82–123. ISSN 0855-3246. JSTOR 41405766. OCLC 5545091926. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ Gocking (2005), p. 30.

- ↑ Haas, Karl J. (2017). "A View From the Periphery: A Re-Assessment of Asante-Dagbamba Relations in the 18th Century". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 50 (2): 205–224. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 44723447.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Davidson (1991), p. 240.

- 1 2 3 Collins & Burns (2007), pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Edgerton (2010), p. 35.

- 1 2 Adjaye, Joseph K. (1985). "Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 18 (3): 487–503. doi:10.2307/218650. JSTOR 179951.

- ↑ Wilks (1989), p. 344.

- ↑ Wilks (1989), p. 40.

- ↑ Wilks (1989), p. 41.

- ↑ "Asante Traditional Buildings". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ↑ Asante, Eric Appau; Kquofi, Steve; Larbi, Stephen (January 2015). "The symbolic significance of motifs on selected Asante religious temples". Journal of Aesthetics & Culture. 7 (1): 27006. doi:10.3402/jac.v7.27006. ISSN 2000-4214.

- ↑ "Ghana Museums & Monuments Board". www.ghanamuseums.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ↑ Edgerton (2010), p. 26.

- ↑ Wilks (1989), p. 376–377.

- ↑ Joseline Donkoh, Wilhelmina (2004). "Kumasi: Ambience of Urbanity and Modernity". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana (8): 167–183. JSTOR 41406712.

- ↑ Wilks 1989, p. 48–;55

- ↑ Wilks 1989, p. 38

- ↑ Wilks 1989, p. 38

- ↑ Edgerton (2010), p. 29–30.

- ↑ Davidson (1991), p. 242.

- ↑ Vandervort, Bruce, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa: 1830–1914, Indiana University Press, 1998, pp. 16–37.

- 1 2 Vandervort (1998).

- ↑ "News.google.com: The Newfoundlander - Dec 16, 1873". Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ↑ Edgerton (2010), p. 56.

- ↑ Kea, R. A. (1971). "Firearms and Warfare on the Gold and Slave Coasts from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries". The Journal of African History. 12 (2): 185–213. doi:10.1017/S002185370001063X. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 180879. S2CID 163027192.

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 24–27.

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 39–53.

- ↑ Anglo-Ashanti wars

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 88–102.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 96.

- ↑ The Downfall of Prepmeh by Robert Baden-Powell, 1896, the American edition is available for download at http://www.thedump.scoutscan.com/dumpinventorybp.php Archived 2016-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ As an aside, Prempeh was banished to the Seychelles. Years later, B-P founded the Boy Scouts, and Prempeh became Chief Scout of Ashanti.

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 172–74.

- ↑ Lloyd, p. 175.

- ↑ "The Daily Advertiser - Google News Archive Search". Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ↑ Gadzekpo (2005), p. 75.

- ↑ Edgerton (2010), p. 40.

- 1 2 Edgerton (2010), pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Perbi, Akosua Adoma (2004). A history of indigenous slavery in Ghana : from the 15th to the 19th century. Legon, Accra, Ghana: Sub-Saharan Publishers. p. 23. ISBN 9789988550325.

- ↑ Alfred Burdon Ellis, The Tshi-speaking peoples of the Gold Coast of West Africa Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, 1887. p. 290

- ↑ Rodriguez, Junius P. The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Volume 1, 1997. p. 53.

- ↑ Johann Gottlieb Christaller, Ashanti Proverbs: (the primitive ethics of a savage people), 1916, pp. 119–20.

- ↑ "Marraige [sic] and Divorce-T.E Kyei". Centre of African Studies. 5 September 2013.

- ↑ Mendelsohn, Daniel (27 November 2000). "Telltale Hearts - Nymag". New York Magazine. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ "Kwasi & Kwame". Jonathan Dove. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ↑ Company, Johnson Publishing (2002-07-01). Jet. Johnson Publishing Company.

Bibliography

- Davidson, Basil, African Civilization Revisited, Africa World Press, 1991, ISBN 9780865431232

- Collins, Robert O.; Burns, James M. (2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521867467.

- Edgerton, Robert B. (2010). The Fall of the Asante Empire: The Hundred-Year War For Africa's Gold Coast. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781451603736.

- Gocking, Roger (2005). The History of Ghana. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31894-8.

- Wilks, Ivor (1989). Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521379946. Retrieved 2020-12-29 – via Books.google.com.

- Shillington, Kevin, 1995 (1989), History of Africa, New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Lloyd, Alan (1964). The Drums of Kumasi: the story of the Ashanti wars. London: Longmans. LCCN 65006132. OL 5937815M.

- Pescheux, Gérard (2003). Le royaume asante (Ghana): parenté, pouvoir, histoire, XVIIe–XXe siècles. Paris: KARTHALA Editions. p. 582. ISBN 2-84586-422-1.

- Gadzekpo, Seth K. (2005). History of Ghana: Since Pre-history. Excellent Pub. and Print. ISBN 9988070810. Retrieved 2020-12-27 – via Books.google.com.

- McCaskie, T. C. (2003). State and Society in Pre-colonial Asante. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521894326.

External links

- the Ashanti Kingdom Encyclopedia - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- UC San Diego - Asante Language Program - Directed Study

- BBC News | Africa | Funeral rites for Ashanti king

- "Osei Tutu", Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

- Asante Catholicism at Googlebooks

- Ashanti Page at the Ethnographic Atlas, maintained at Centre for Social Anthropology and Computing, University of Kent, Canterbury

- Ashanti Kingdom at the Wonders of the African World, at PBS

- Ashanti Culture contains a selected list of Internet sources on the topic, especially sites that serve as comprehensive lists or gateways

- The Story of Africa: Asante — BBC World Service

- Web dossier about the Asante Kingdom: African Studies Centre, Leiden

- "Asante empire", Encyclopædia Britannica.