| Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka | |

|---|---|

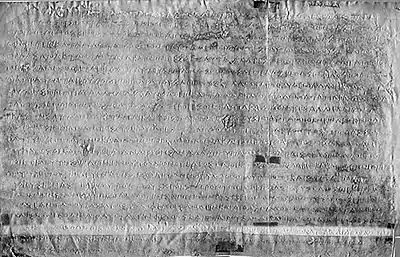

Greek inscription by king Ashoka, discovered in Kandahar | |

| Material | Sandstone tablet |

| Size | 45 by 69.5 centimetres (17.7 in × 27.4 in) |

| Writing | Greek |

| Created | circa 258 BCE |

| Period/culture | 3rd Century BCE |

| Discovered | 31°36′09N 65°39′32E |

| Place | Old Kandahar, Kandahar, Afghanistan |

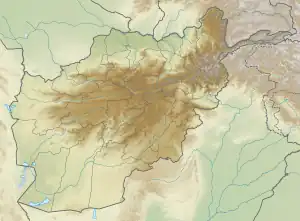

The Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka are among the Major Rock Edicts of the Indian Emperor Ashoka (reigned 269-233 BCE), which were written in the Greek language and Prakrit language. They were found in the ancient area of Old Kandahar (known as Zor Shar in Pashto, or Shahr-i-Kona in Persian) in Kandahar in 1963.[1] It is thought that Old Kandahar was founded in the 4th century BCE by Alexander the Great, who gave it the Ancient Greek name Ἀλεξάνδρεια Ἀραχωσίας (Alexandria of Arachosia).

The extant edicts are found in a plaque of limestone, which probably belonged to a building, and its size is 45 by 69.5 centimetres (17.7 in × 27.4 in) and it is about 12 centimetres (4.7 in) thick. These are the only Ashoka inscriptions thought to have belonged to a stone building.[1][2] The beginning and the end of the fragment are lacking, which suggests the inscription was original significantly longer, and may have included all 14 of Ashoka's Edicts in Greek, as in several other locations in India.[2] The plaque with the inscription was bought in the Kandahar market by the German doctor Seyring, and French archaeologists found that it had been excavated in Old Kandahar. The plaque was then offered to the Kabul Museum,[3] but its current location is unknown following the looting of the museum in 1992–1994.[4]

Background

Greek communities lived in the northwest of the Mauryan empire, currently in Pakistan, notably ancient Gandhara near the current Pakistani capital of Islamabad and in the region of Gedrosia, and presently in Southern Afghanistan, following the conquest and the colonization efforts of Alexander the Great around 323 BCE. These communities therefore were significant in the area of Afghanistan during the reign of Ashoka.[5]

Content

The Edict is a Greek version of the end of the 12th Edicts (which describes moral precepts) and the beginning of the 13th Edict (which describes the King's remorse and conversion after the war in Kalinga), which makes it a portion of a Major Rock Edict.[6] This inscription does not use another language in parallel, contrary to the famous Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription in Greek language and Aramaic, discovered in the same general area.[7]

The Greek language used in the inscription is of a very high level and displays philosophical refinement. It also displays an in-depth understanding of the political language of the Hellenic world in the 3rd century BCE. This suggests the presence of a highly cultured Greek presence in Kandahar at that time.[2]

Implications

The proclamation of this edict in Kandahar is usually taken as proof that Ashoka had control over that part of Afghanistan, presumably after Seleucus I had ceded this territory to Chandragupta Maurya in their 305 BCE peace agreement.[1] The Edict also shows the presence of a sizable Greek population in the area[5][8] where great efforts were made to convert them to Buddhism.[9] At the same epoch, the Greeks were established in the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, and particularly in the border city of Ai-Khanoum, in the northern part of Afghanistan.

Translation

| English translation | Original Greek text |

|---|---|

|

|

Other inscriptions in Greek in Kandahar

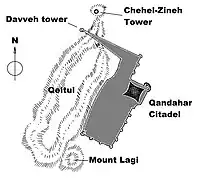

The Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription, discovered in 1958, is the other well-known Greek inscription by Ashoka in the area of Kandahar. It was found on the mountainside of the Chil Zena outcrop on the western side of the city of Kandahar.

Two other inscriptions in Greek are known at Kandahar. One is a dedication by a Greek man who names himself "son of Aristonax" (3rd century BCE). The other is an elegiac composition by Sophytos son of Naratos (2nd century BCE).[12]

Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription in Greek and Aramaic, by Emperor Ashoka, 3rd century BCE, Kandahar.

Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription in Greek and Aramaic, by Emperor Ashoka, 3rd century BCE, Kandahar. Inscription in Greek by the "son of Aristonax", 3rd century BCE, Kandahar.

Inscription in Greek by the "son of Aristonax", 3rd century BCE, Kandahar. Kandahar Sophytos Inscription, 2nd century BCE, Kandahar.

Kandahar Sophytos Inscription, 2nd century BCE, Kandahar. Plan of ancient fortifications of Kandahar.

Plan of ancient fortifications of Kandahar.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Dupree, L. (2014). Afghanistan. Princeton University Press. p. 287. ISBN 9781400858910. Retrieved 2016-11-27.

- 1 2 3 Une nouvelle inscription grecque d'Açoka, Schlumberger, Daniel, Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres Année 1964 Volume 108 Numéro 1 pp. 126-140

- ↑ "Kabul Museum p.9" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-28. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- ↑ Archaeology "Museum Under Siege" April 20, 1998

- 1 2 3 Dupree, L. (2014). Afghanistan. Princeton University Press. p. 286. ISBN 9781400858910. Retrieved 2016-11-27.

- ↑ "Asoka, Romilla Thapar" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- ↑ Rome, the Greek World, and the East: Volume 1: The Roman Republic and the Augustan Revolution, Fergus Millar, Univ of North Carolina Press, 2003, p.45

- ↑ Indian Hist (Opt). McGraw-Hill Education (India) Pvt Limited. 2006. p. 1:183. ISBN 9780070635777. Retrieved 2016-11-27.

- ↑ Halkias, G. (2014), When the Greeks Converted The Buddha: Asymmetrical Transfers of Knowledge in Indo-Greek CulturesLeiden: Brill, pp. 65-116

- ↑ "Afghanistan", Louis Dupree, Princeton University Press, 2014, p.286

- ↑ Schlumberger, Daniel (1964). "Une nouvelle inscription grecque d'Açoka". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 108e année, N. 1: 131. doi:10.3406/crai.1964.11695. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ↑ The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Greek Religion, Esther Eidinow, Julia Kindt, Oxford University Press, 2015