| Taiwan Expedition of 1874 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Formosa Conflict | |||||||||

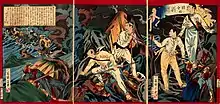

Commander-in-chief Saigo (sitting at the center) pictured with leaders of the Seqalu tribe.  The Assault at Sekimon (石門進撃), May 22, 1874. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| Botan | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| Unknown (DOW) | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Land: 3,600 Sea: 6 warships | Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

12 killed ~30 wounded 561 died from disease[3] |

89 killed Many wounded | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Japanese punitive expedition to Taiwan in 1874, referred to in Japan as the Taiwan Expedition (Japanese: 台湾出兵, Hepburn: Taiwan Shuppei) and in Taiwan and Mainland China as the Mudan incident (Chinese: 牡丹社事件), was a punitive expedition launched by the Japanese ostensibly in retaliation for the murder of 54 Ryukyuan sailors by Paiwan aborigines near the southwestern tip of Taiwan in December 1871. In May 1874, the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the indigenous Taiwanese peoples in southern Taiwan and retreated in December after the Qing dynasty agreed to pay an indemnity of 500,000 taels. Some ambiguous wording in the agreed terms were later argued by Japan to be confirmation of Chinese renunciation of suzerainty over the Ryukyu Islands, paving the way for de facto Japanese incorporation of the Ryukyu in 1879.

Background

Mudan incident

In December 1871, a Ryukyuan vessel shipwrecked on the southeastern tip of Taiwan and 54 sailors were killed by aborigines. Four tribute ships were returning to the Ryukyu Islands when they were blown off course on 12 December. Two ships were pushed towards Taiwan. One of them landed on Taiwan's western coast and made it back home with the help of Qing officials. The other one crashed into the eastern coast of southern Taiwan near Bayao Bay. There were 69 passengers and 66 managed to make it to shore. Fifty-four of them were killed by Paiwan while the remaining 12 were rescued by Han Chinese who transferred them to Taiwan Prefecture (modern Tainan). They then made their way to Fujian province in mainland China and from there, the Qing government arranged transport to send them home. They departed in July 1872[5]

This event, known as the Mudan incident, did not immediately cause any concern in Japan. A few officials knew of it by mid-1872 but it was not until April 1874 that it became an international concern. The repatriation procedure in 1872 was by the books and had been a regular affair for several centuries. From the 17th to 19th centuries, the Qing had settled 401 Ryukyuan shipwreck incidents both on the coast of mainland China and Taiwan. The Ryukyu Kingdom did not ask Japanese officials for help regarding the shipwreck. Instead its king, Shō Tai, sent a reward to Chinese officials in Fuzhou for the return of the 12 survivors.[6]

Diplomacy

On 30 August 1872, Sukenori Kabayama, a general of the Imperial Japanese Army, urged the Japanese government to invade Taiwan's tribal areas. In September, Japan dethroned the king of Ryukyu. On 9 October, Kabayama was ordered to conduct a survey in Taiwan. In 1873, Tanemomi Soejima was sent to communicate to the Qing court that if it did not extend its rule to the entirety of Taiwan, punish murderers, pay victims' families' compensation, and refused to talk about the matter, Japan would take care of the matter. The Foreign Minister Sakimitsu Yanagihara believed that the perpetrators of the Mudan incident were "all Taiwan savages beyond Chinese education and law."[7] Japan justified sending an expedition to Taiwan through linguistic interpretation of huawai zhimin (lit. outside the sphere of civilization) to mean not part of China. Chinese diplomat Li Hongzhang rejected the claim that the murder of Ryukyuans had anything to do with Japan once he learned of Japan's aspirations.[8] However, after communications between the Qing and Yanagihara, the Japanese took their explanation to mean that the Qing government had not opposed Japan's claims to sovereignty over the Ryukyu Islands, disclaimed any jurisdiction over Aboriginal Taiwanese, and had indeed consented to Japan's expedition to Taiwan.[9] In the eyes of Japan and the foreign advisor Charles Le Gendre, the aborigines were "savages" who had no sovereign or international status, and therefore their territory was "terra nullius", free to be seized for Japan.[10] The Qing argued that like in many other countries, the administration of the government did not stretch to every part of a country, similar to the Indian territories in the United States or aboriginal territories in Australia and New Zealand, a view Le Gendre also took before his employment by the Japanese.[11]

Japan had already sent a student, Kurooka Yunojo, to conduct surveys in Taiwan in April 1873. Kabayama reached Tamsui on 23 August disguised as a merchant and surveyed eastern Taiwan.[8] On 9 March 1874, the Taiwan Expedition prepared for its mission. The magistrate of the Taiwan Circuit learned of the impending Japanese invasion from a Hong Kong newspaper quoting a Japanese news item and reported it to Fujian authorities.[12] Qing officials were taken by complete surprise due to the seemingly cordial relations with Japan at the time. On 17 May, Saigō Jūdō led the main force, 3,600 strong, aboard four warships in Nagasaki headed to Tainan.[13] On 6 June, the Japanese emperor issued a certificate condemning the Taiwan "savages" for killing our "nationals", the Ryukyuans killed in southeastern Taiwan.[14]

Expedition

On 3 May 1874, Kusei Fukushima delivered a note to Fujian-Zhejiang Governor Li Henian announcing that they were heading to savage territory to punish the culprits.[16]

On 6 May the Japanese landed a small force commanded by Douglas R. Cassel to select a campsite fortified by the sea.[17] On 7 May, a Chinese translator, Zhan Hansheng, was sent ashore to establish peaceful relations with tribes other than the Mudan and Kuskus.[16]

American foreign officers and Fukushima landed at Checheng and Xinjie. They tried to use Baxian Bay at Qinggangpu as their barracks but heavy rain flooded the site a few days later so the Japanese moved to the southern end of Langqiao Bay on 11 May. They learned that Tanketok had died and invited the Shemali tribe for talks. Japanese scouts fanned out and were met by attacks by aborigines.[16] On 15 May, Cassel acted as a negotiator to Chief Issa (Chinese: 伊厝), head of the island's sixteen southern tribes. Chief Issa stated the "Botans" were out of his control, and gave the Japanese his consent to punish them as they wished.[18]

On 17 May, a 100 man party went inland to scout for another camp location, and from this party a dozen split off to investigate a village. Despite being within friendly territory, this small group was ambushed by the Botans. In the ensuing skirmish one Japanese soldier was wounded in the neck and a sergeant from Satsuma killed. The small Japanese group retreated back to the main force, and upon returning found the sergeant had been decapitated by the aborigines, his head taken as a trophy.[19]

On 18 May the Japanese ship Nisshin commanded by Akamatsu Noriyoshi anchored in Kwaliang bay and launched a small boat to conduct surveys. Aborigines from the village Koalut fired upon the boat with muskets. Despite receiving no injuries, Akamatsu was enraged at the incident and made immediate plans not only for attack on Koalut, but the nearby village of Lingluan as well. These plans would be postponed and eventually cancelled.[19]

On 21 May, a detachment of 12 men was sent out to investigate the area where the Satsuma sergeant had been killed. During this investigation the detachment was ambushed again by a group of 50 natives and in the exchange of fire two Japanese were seriously wounded and one attacker was killed. The Japanese returned hastily to the shore and sounded the alarm, and 250 men accompanied by Wasson marched inland to respond. Wasson was dismayed at the lack of discipline of the Japanese soldiers, particularly in the rear, who quickly broke rank and dashed ahead in a race to get to combat first. The natives retreated after the arrival of the main force.[20]

Saigō arrived with more troops on 22 May. Colonel Sakuma Samata commanding a 150-strong force marched too far inland and was ambushed by 70 Mudan fighters, commencing the Battle of Stone Gate. The aborigines were already in pre-selected ambush positions behind stone, while the Japanese had to make do with what cover they could find from rocks seated in the waist-deep river and only being able to employ 30 troops at one time due to the terrain. Early in the engagement Sakuma ordered a retreat, but was completely ignored by his troops who continued to fight. The fighting lasted a little over an hour, until Sakuma ordered 20 riflemen to scale a cliff to his left and fire on the natives from above while the men in the river continued to press them. Upon seeing the 20 riflemen atop the cliff, the natives retreated. The Mudan lost 16 men including their chief, Agulu, and his son with many more wounded.[21] The Japanese suffered seven casualties including an officer and 30 wounded.[16]

The Japanese army split into three forces and headed in different directions, the south, north, and central routes. The south route army was ambushed by the Kuskus tribe and lost three soldiers. A counterattack defeated the Kuskus fighter and the Japanese burnt their villages. The central route was attacked by Mudan and two or three soldiers were wounded. The Japanese burnt their villages. The north route attacked the Nünai village. On 3 June, they burnt all the villages that had been occupied. On 1 July, the new leader of the Mudan tribe and the chief of Kuskus admitted defeat and promised not to harm shipwrecked castaways.[22] Surrendered aborigines were given Japanese flags to fly over their villages. They were viewed as a symbol of peace with Japan and protection from rival tribes by the aborigines. To the Japanese, it was a symbol of jurisdiction over the aborigines.[23] Chinese forces arrived on 17 June and a report by Fujian Administration Commissioner reported that all 56 representatives of the tribes except for Mudan, Zhongshe and Linai, who were not present due to fleeing from the Japanese, complained about Japanese bullying.[24]

A Chinese representative, Pan Wei, met with Saigō four times between 22 and 26 June but nothing came of it. The Japanese settled in and established large camps with no intention of withdrawing, but in July, there was an outbreak of malaria. Both American foreign advisors contracted it, and while Wasson survived, Cassel died from the malaria he contracted on the expedition in spring the next year, 1875.[4] In August and September 600 soldiers fell ill. They started dying 15 a day. The death toll rose to 561. Toshimichi Okubo arrived in Beijing on 10 September and seven negotiating sessions occurred over a month long period. The Western Powers pressured China not to cause bloodshed with Japan as it would negatively impact the coastal trade. The resulting Peking Agreement was signed on 30 October. Japan gained the recognition of Ryukyu as its vassal and an indemnity payment of 500,000 taels. Japanese troops withdrew from Taiwan on 3 December.[25]

Legacy

Although launched ostensibly to punish the local tribesmen for their murder of 54 Ryukyuan merchants, the 1874 punitive expedition to Taiwan served a number of purposes for Japan's new Meiji government. Japan had for some time begun claiming suzerainty, and later sovereignty, over the Ryūkyū Kingdom, whose traditional suzerain had been China, though it had also been a feudatory of the by then defunct Satsuma Domain since the 17th century. The expedition demonstrated that China was not in effective control of Taiwan, let alone the Ryukyu Islands. Japan was emboldened to more forcefully assert its claim to speak for the Ryukyuan islanders. The settlement in 1874, brokered by the British, included a reference to Chinese recognition that the Japanese expedition was "in protection of civilians", a reference that Japan later pointed towards as Chinese renunciation of its rights over Ryukyu. In 1879 Japan referred the dispute to British arbitration, and the British confirmed Japanese sovereignty over the Ryukyus, a result which was not recognised by China.[26]

The surrendering aborigines were given Japanese flags to fly over their villages that they viewed as a symbol of peace with Japan and protection from rival tribes, however, the Japanese viewed them as a symbol of jurisdiction over the aborigines.[27] The expedition also served as a useful rehearsal for future Japanese imperial ambitions. Taiwan was already being viewed as a potential Japanese colony in some circles in Japan.[28]

More generally, the Japanese incursion into Taiwan in 1874 and the feeble Chinese response was a blatant revelation of Chinese weakness and an invitation to further foreign encroachment in Taiwan. In particular, the success of the Japanese incursion was among the factors influencing the French decision to invade Taiwan in October 1884, during the Sino-French War. The Qing court belatedly attempted to strengthen its hold on Taiwan. Chinese imperial commissioner Shen Baozhen built the Batongguan Trail in 1875 across the island's rugged interior to encourage Han settlement in the mountains and better subjugate the indigenous population.[29][30]

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- ↑ "WASHINGTON.; OFFICIAL DISPATCHES ON THE FORMOSA DIFFICULTY. PARTIAL OCCUPATION OF THE ISLAND BY JAPANESE THE ATTITUDE OF CHINA UNCERTAIN CHARACTER OF THE FORMOSAN BARBARIANS. THE RAILROAD AND THE MAILS. THE VACANT INSPECTOR GENERALSHIP OF STEAMBOATS. THE TREATY OF WASHINGTON. THE CURRENCY BANKS AUTHORIZED CIRCULATION WITHDRAWN. POSTMASTERS APPOINTED. APPOINTMENT OF AN INDIAN COMMISSIONER. THE WRECK OF THE SCOTLAND, NEW-YORK HARBOR. NAVAL ORDERS. TOLL ON VESSELS ENGAGED IN FOREIGN COMMERCE. THE TREASURY SECRET SERVICE. TREASURY BALANCES". New York Times. Washington. August 18, 1874.

- ↑ Eskildsen, Robert (2010). "An Army as Good and Efficient as Any in the World: James Wasson and Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan" (PDF). Asian Cultural Studies (36): 52–56.

- ↑ アジア歴史資料センター, A03030094100, 正院修史局ヘ征台ノ節出兵総数死傷人員其外問合ニ付回答(国立公文書館)「JACAR(アジア歴史資料センター)Ref.A03030094100、単行書・処蕃書類追録九(国立公文書館)」。

- 1 2 Cunningham p. 7

- ↑ Barclay 2018, p. 51-52.

- ↑ Barclay 2018, p. 53-54.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 124-126.

- 1 2 Wong 2022, p. 127-128.

- ↑ Leung (1983), p. 270.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 185-186.

- ↑ Ye 2019, p. 187.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 129.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 132.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 130.

- ↑ Huffman, James L. (2003). A Yankee in Meiji Japan. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 94. ISBN 9780742526211.

- 1 2 3 4 Wong 2022, p. 134-137.

- ↑ Cunningham p. 6

- ↑ Cunningham p. 6

- 1 2 Eskildsen, Robert. An Army as Good and Efficient as Any in the World: James Wasson and Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan (Asian Cultural Studies 36, 2010), p. 55

- ↑ Eskildsen, Robert. An Army as Good and Efficient as Any in the World: James Wasson and Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan (Asian Cultural Studies 36, 2010), pp. 56–57

- ↑ House p. 91

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 137-138.

- ↑ "| of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan | the American Historical Review, 107.2 | the History Cooperative". Archived from the original on 2010-12-12. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 138.

- ↑ Wong 2022, p. 141-143.

- ↑ Kerr (2000), pp. 359–360.

- ↑ "| of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan | the American Historical Review, 107.2 | the History Cooperative". Archived from the original on 2010-12-12. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ↑ Eskildsen, Robert (2002). "Of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan". The American Historical Review. 107 (2): 388–418. doi:10.1086/532291.

- ↑ "八通關古道". National Cultural Heritage Database Management System (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Bureau of Cultural Heritage. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ↑ 楊南邵 (1989). 玉山國家公園八通關古道東段調查研究報告 (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Academia Sinica. pp. 37–38. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

Bibliography

- Barclay, Paul D. (2018), Outcasts of Empire: Japan's Rule on Taiwan's "Savage Border," 1874-1945, University of California Press

- Chiu, Hungdah (1979). China and the Taiwan Issue. London: Praeger. ISBN 0-03-048911-3.

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects : tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1887893. OL 6931635M.

- House, Edward H. (May 2018). The Japanese Expedition to Formosa. Forgotten Books. ISBN 9780282270940.

- Kerr, George (2000) [1958]. Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Afterword by Mitsugu Sakihara (revised ed.). Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9780804820875.

- Leung, Edwin Pak-Wah (1983), "The Quasi-War in East Asia: Japan's Expedition to Taiwan and the Ryūkyū Controversy", Modern Asian Studies, 17 (2): 257–281, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00015638, S2CID 144573801.

- Paine, S.C.M (2002). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81714-5.

- Ravina, Mark (2003). The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-08970-2.

- Roger D., Cunningham (2004). A Conspicuous Ornament: The Short, Eventful Life of Lt. Cdr. Douglas R. Cassel, U.S.N. Journal of America's Military Past.

- Smits, Gregory (1999). Visions of Ryūkyū: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Wong, Tin (2022), Approaching Sovereignty over the Diaoyu Islands, Springer

- Ye, Ruiping (2019), The Colonisation and Settlement of Taiwan, Routledge

Further reading

- House, Edward H. (1875). The Japanese Expedition to Formosa. Tokio. OCLC 602178265. OL 6954039M.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Eskildsen, Robert (2002). "Of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan". The American Historical Review. 107 (2): 388–418. doi:10.1086/532291.

External links

Media related to Taiwan Expedition of 1874 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Taiwan Expedition of 1874 at Wikimedia Commons