| First Sino-Japanese War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Century of humiliation | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Within theatre of operations 180,310 bannermen 51,760 Green Standard 125,030 Trained men Total 357,100 |

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

Total: 17,069 casualties | ||||||||

| First Sino-Japanese War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

-Long_live_the_Great_Japanese_Empire!_Our_army's_victorious_attack_on_Seonghwan.jpg.webp) | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 甲午戰爭 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 甲午战争 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | War of Jiawu – referring to the year 1894 under the traditional sexagenary system | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 日清戦争 | ||||||

| Kyūjitai | 日清戰爭 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Japan–Qing War | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 청일전쟁 | ||||||

| Hanja | 淸日戰爭 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Qing–Japan War | ||||||

| |||||||

| Events leading to World War I |

|---|

|

|

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) or the First China–Japan War was a conflict between the Qing dynasty and Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Korea.[2] After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the port of Weihaiwei, the Qing government sued for peace in February 1895.

The war demonstrated the failure of the Qing dynasty's attempts to modernize its military and fend off threats to its sovereignty, especially when compared with Japan's successful Meiji Restoration. For the first time, regional dominance in East Asia shifted from China to Japan;[3] the prestige of the Qing dynasty, along with the classical tradition in China, suffered a major blow. The humiliating loss of Korea as a tributary state sparked an unprecedented public outcry. Within China, the defeat was a catalyst for a series of political upheavals led by Sun Yat-sen and Kang Youwei, culminating in the 1911 Revolution and ultimate end of dynastic rule in China.

The war is commonly known in China as the War of Jiawu (Chinese: 甲午戰爭; pinyin: Jiǎwǔ Zhànzhēng), referring to the year (1894) as named under the traditional sexagenary system of years. In Japan, it is called the Japan–Qing War (Japanese: 日清戦争, Hepburn: Nisshin sensō). In Korea, where much of the war took place, it is called the Qing–Japan War (Korean: 청일전쟁; Hanja: 淸日戰爭).

Background

After two centuries, the Japanese policy of seclusion under the shōguns of the Edo period came to an end when the country was opened to trade by the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854. In the years following the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the fall of the shogunate, the newly formed Meiji government embarked on reforms to centralize and modernize Japan.[4] The Japanese had sent delegations and students around the world to learn and assimilate Western arts and sciences, with the intention of making Japan an equal to the Western powers.[5] These reforms transformed Japan from a feudal society into a modern industrial state.

During the same time period, the Qing dynasty also started to undergo reform in both military and political doctrine, but was far less successful.

Korean politics

In January 1864, King Cheoljong died without a male heir, and through Korean succession protocols King Gojong ascended the throne at the age of 12. However, as King Gojong was too young to rule, the new king's father, Yi Ha-ŭng, became the Daewongun, or lord of the great court, and ruled Korea in his son's name as regent.[6] Originally the term Daewongun referred to any person who was not actually the king but whose son took the throne.[6] With his ascendancy to power the Daewongun initiated a set of reforms designed to strengthen the monarchy at the expense of the Yangban class. He also pursued an isolationist policy and was determined to purge the kingdom of any foreign ideas that had infiltrated into the nation.[7] In Korean history, the king's in-laws enjoyed great power, consequently the Daewongun acknowledged that any future daughters-in-law might threaten his authority.[8] Therefore, he attempted to prevent any possible threat to his rule by selecting as a new queen for his son an orphaned girl from among the Yŏhŭng Min clan, which lacked powerful political connections.[9] With Queen Min as his daughter-in-law and the royal consort, the Daewongun felt secure in his power.[9] However, after she had become queen, Min recruited all her relatives and had them appointed to influential positions in the name of the king. The Queen also allied herself with political enemies of the Daewongun, so that by late 1873 she had mobilized enough influence to oust him from power.[9] In October 1873, when the Confucian scholar Choe Ik-hyeon submitted a memorial to King Gojong urging him to rule in his own right, Queen Min seized the opportunity to force her father-in-law's retirement as regent.[9] The departure of the Daewongun led to Korea's abandonment of its isolationist policy.[9]

Opening of Korea

On February 26, 1876, after confrontations between the Japanese and Koreans, the Ganghwa Treaty was signed, opening Korea to Japanese trade. In 1880, the King sent a mission to Japan that was headed by Kim Hong-jip, an enthusiastic observer of the reforms taking place there.[10] While in Japan, the Chinese diplomat Huang Zunxian presented him with a study called "A Strategy for Korea" (Chinese: 朝鮮策略; pinyin: Cháoxiǎn cèlüè).[10] It warned of the threat to Korea posed by the Russians and recommended that Korea maintain friendly relations with Japan, which was at the time too economically weak to be an immediate threat, to work closely with China, and seek an alliance with the United States as a counterweight to Russia.[11] After returning to Korea, Kim presented the document to King Gojong, who was so impressed with the document that he had copies made and distributed to his officials.[12]

In 1880, following Chinese advice and breaking with tradition, King Gojong decided to establish diplomatic ties with the United States.[13] After negotiations through Chinese mediation in Tianjin, the Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce, and Navigation was formally signed between the United States and Korea in Incheon on May 22, 1882.[13] However, there were two significant issues raised by the treaty. The first concerned Korea's status as an independent nation. During the talks with the Americans, the Chinese insisted that the treaty contain an article declaring that Korea was a dependency of China and argued that the country had long been a tributary state of China.[13] But the Americans firmly opposed such an article, arguing that a treaty with Korea should be based on the Treaty of Ganghwa, which stipulated that Korea was an independent state.[14] A compromise was finally reached, with Shufeldt and Li agreeing that the King of Korea would notify the U.S. president in a letter that Korea had special status as a tributary state of China.[14] The treaty between the Korean government and the United States became the model for all treaties between it and other Western countries. Korea later signed similar trade and commerce treaties with Great Britain and Germany in 1883, with Italy and Russia in 1884, and with France in 1886. Subsequently, commercial treaties were concluded with other European countries.[15]

Korean reforms

After 1879, China's relations with Korea came under the authority of Li Hongzhang, who had emerged as one of the most influential figures in China after playing an important role during the Taiping Rebellion, and was also an advocate of the Self-Strengthening Movement.[12] In 1879, Li was appointed as governor-general of Zhili Province and the imperial commissioner for the northern ports. He was in charge of China's Korea policy and urged Korean officials to adopt China's own self-strengthening program to strengthen their country in response to foreign threats, to which King Gojong was receptive.[12] The Korean government, immediately after opening the country to the outside world, pursued a policy of enlightenment aimed at achieving national prosperity and military strength through the doctrine of tongdo sŏgi (Eastern ways and Western machines).[15] To modernize their country, the Koreans tried selectively to accept and master Western technology while preserving their country's cultural values and heritage.[15]

In January 1881, the government launched administrative reforms and established the T'ongni kimu amun (Office for Extraordinary State Affairs) which was modeled on Chinese administrative structures.[15] Under this overarching organization, twelve sa or agencies were created.[15] In 1881, a technical mission was sent to Japan to survey its modernized facilities.[16] Officials traveled all over Japan inspecting administrative, military, educational, and industrial facilities.[16] In October, another small group went to Tianjin to study modern weapons manufacturing, and Chinese technicians were invited to manufacture weapons in Seoul. Additionally, as part of their plan to modernize the country, the Koreans had invited the Japanese military attaché Lieutenant Horimoto Reizō to serve as an adviser in creating a modern army.[17] A new military formation called the Pyŏlgigun (Special Skills Force) was established, in which eighty to one hundred young men[18] of the aristocracy were to be given Japanese military training.[19] The following year, in January 1882, the government also reorganized the existing five-army garrison structure into the Muwiyŏng (Palace Guards Garrison) and the Changŏyŏng (Capital Guards Garrison).[15]

Japanese insecurities over Korea

During the 1880s, discussions in Japan about national security focused on the issue of Korean reform. The political discourse over the two were interlinked; as the German military adviser Major Jacob Meckel stated, Korea was "a dagger pointed at the heart of Japan".[20] What made Korea of strategic concern was not merely its proximity to Japan but its inability to defend itself against outsiders. If Korea were truly independent, it posed no strategic problem to Japan's national security, but if the country remained undeveloped it would remain weak and consequently would be inviting prey for foreign domination.[21] The political consensus in Japan was that Korean independence lay, as it had been for Meiji Japan, through the importation of "civilization" from the West.[20] Korea required a program of self-strengthening like the post-Restoration reforms that were enacted in Japan.[21] The Japanese interest in the reform of Korea was not purely altruistic. Not only would these reforms enable Korea to resist foreign intrusion, which was in Japan's direct interest, but through being a conduit of change they would also have opportunity to play a larger role on the peninsula.[20] To Meiji leaders, the issue was not whether Korea should be reformed but how these reforms might be implemented. There was a choice of adopting a passive role which required the cultivation of reformist elements within Korean society and rendering them assistance whenever possible, or adopting a more aggressive policy, actively interfering in Korean politics to assure that reform took place.[22] Many Japanese advocates of Korean reform swung between these two positions.

Japan in the early 1880s was weak, as a result of internal peasant uprisings and samurai rebellions during the previous decade. The country was also struggling financially, with inflation as a result of these internal factors. Subsequently, the Meiji government adopted a passive policy, encouraging the Korean court to follow the Japanese model but offering little concrete assistance except for the dispatch of the small military mission headed by Lieutenant Horimoto Reizo to train the Pyŏlgigun.[22] What worried the Japanese was the Chinese, who had loosened their hold over Korea in 1876 when the Japanese succeeded in establishing a legal basis for Korean independence by ending its tributary status.[23] Chinese actions appeared to be thwarting the forces of reform in Korea and re-asserting their influence over the country.[23]

1882 crisis

In 1882, the Korean Peninsula experienced a severe drought which led to food shortages, causing much hardship and discord among the population. Korea was on the verge of bankruptcy, even falling months behind on military pay, causing deep resentment among the soldiers. There was also resentment towards the Pyŏlgigun on the part of the soldiers of the regular Korean army, as the formation was better equipped and treated.[17] Additionally, more than 1000 soldiers had been discharged in the process of overhauling the army; most of them were either old or disabled, and the rest had not been given their pay in rice for thirteen months.[19]

In June of that year, King Gojong, being informed of the situation, ordered that a month's allowance of rice be given to the soldiers.[19] He directed Min Gyeom-ho, the overseer of government finances and Queen Min's nephew,[24] to handle the matter. Min in turn handed the matter over to his steward who sold the good rice he had been given and used the money to buy millet which he mixed with sand and bran.[19] As a result, the rice became rotten and inedible. The distribution of the alleged rice infuriated the soldiers. On July 23, a military mutiny and riot broke out in Seoul. Enraged soldiers headed for the residence of Min Gyeom-ho, who they had suspected of having swindled them out of their rice.[19] Min, on hearing word of the revolt, ordered the police to arrest some of the ringleaders and announced that they would be executed the next morning. He had assumed that this would serve as a warning to the other agitators. However, after learning what had transpired, the rioters broke into Min's house to take vengeance; as he was not at his residence the rioters vented their frustrations by destroying his furniture and other possessions.[19]

The rioters then moved on to an armory from which they stole weapons and ammunition, and then headed for the prison. After overpowering the guards, they released not only the men who had been arrested that day by Min Gyeom-ho but also many political prisoners as well.[19] Min then summoned the army to quell the rebellion but it had become too late to suppress the mutiny. The original body of mutineers had been swelled by the poor and disaffected citizenry of the city; as a result the revolt had assumed major proportions.[19] The rioters now turned their attention to the Japanese. One group headed to Lieutenant Horimoto's quarters and killed him.[19] Another group, some 3,000 strong, headed for the Japanese legation, where Hanabusa Yoshitada the minister to Korea and twenty seven members of the legation resided.[19] The mob surrounded the legation shouting its intention of killing all the Japanese inside.[19] Hanabusa gave orders to burn the legation and important documents were set on fire. As the flames quickly spread, the members of the legation escaped through a rear gate, where they fled to the harbor and boarded a boat which took them down the Han River to Chemulpo. Taking refuge with the Incheon commandant, they were again forced to flee after word arrived of the events in Seoul and the attitude of their hosts changed. They escaped to the harbor during heavy rain and were pursued by Korean soldiers. Six Japanese were killed, while another five were seriously wounded.[19] The survivors carrying the wounded then boarded a small boat and headed for the open sea where three days later they were rescued by a British survey ship, HMS Flying Fish,[25] which took them to Nagasaki. The following day, after the attack on the Japanese legation, the rioters forced their way into the royal palace where they found and killed Min Gyeom-ho, as well as a dozen other high-ranking officers.[25] They also searched for Queen Min. The queen narrowly escaped, however, dressed as an ordinary lady of the court and was carried on the back of a faithful guard who claimed she was his sister.[25] The Daewongun used the incident to reassert his power.

The Chinese then deployed about 4,500 troops to Korea, under General Wu Changqing, which effectively regained control and quelled the rebellion.[26] In response, the Japanese also sent four warships and a battalion of troops to Seoul to safeguard Japanese interests and demand reparations. However, tensions subsided with the Treaty of Chemulpo, signed on the evening of August 30, 1882. The agreement specified that the Korean conspirators would be punished and ¥50,000 would be paid to the families of slain Japanese. The Japanese government would also receive ¥500,000, a formal apology, and permission to station troops at their diplomatic legation in Seoul. In the aftermath of rebellion, the Daewongun was accused of fomenting the rebellion and its violence, and was arrested by the Chinese and taken to Tianjin.[27] He was later carried off to a town about sixty miles southwest of Beijing, where for three years he was confined to one room and kept under strict surveillance.[28]

Re-assertion of Chinese influence

After the Imo Incident, early reform efforts in Korea suffered a major setback.[29] In the aftermath of the incident, the Chinese reasserted their influence over the peninsula, where they began to interfere in Korean internal affairs directly.[29] After stationing troops at strategic points in the capital Seoul, the Chinese undertook several initiatives to gain significant influence over the Korean government.[30] The Qing dispatched two special advisers on foreign affairs representing Chinese interests to Korea: the German Paul Georg von Möllendorff, a close confidant of Li Hongzhang, and the Chinese diplomat Ma Jianzhong.[31] A staff of Chinese officers also took over the training of the army, providing the Koreans with 1,000 rifles, two cannons, and 10,000 rounds of ammunition.[32] Furthermore, the Chingunyeong (Capital Guards Command), a new Korean military formation, was created and trained along Chinese lines by Yuan Shikai.[31]

In October, the two countries signed a treaty stipulating that Korea was dependent on China and granted Chinese merchants the right to conduct overland and maritime business freely within its borders. It also gave the Chinese advantages over the Japanese and Westerners and granted them unilateral extraterritoriality privileges in civil and criminal cases.[32] Under the treaty, the number of Chinese merchants and traders significantly increased, a severe blow to Korean merchants.[31] Although it allowed Koreans reciprocally to trade in Beijing, the agreement was not a treaty but was in effect issued as a regulation for a vassal.[29] Additionally, during the following year, the Chinese supervised the creation of a Korean Maritime Customs Service, headed by von Möllendorff.[29] Korea was reduced to a semi-colonial tributary state of China with King Gojong unable to appoint diplomats without Chinese approval,[31] and with troops stationed in the country to protect Chinese interests.[nb 1] China also obtained concessions in Korea, notably the Chinese concession of Incheon.[33][34]

Factional rivalry and ascendancy of the Min clan

During the 1880s two rival factions emerged in Korea. One was a small group of reformers that had centered around the Gaehwadang (Enlightenment Party), which had become frustrated at the limited scale and arbitrary pace of reforms.[29] The members who constituted the Enlightenment Party were well-educated Koreans and most were from the yangban class.[29] They were impressed by the developments in Meiji Japan and were eager to emulate them.[29] Members included Kim Ok-gyun, Pak Yung-hio, Hong Yeong-sik, Seo Gwang-beom, and Soh Jaipil.[35] The group was also relatively young; Pak Yung-hio came from a prestigious lineage related to the royal family and was 23, Hong was 29, Seo Gwang-beom was 25, and Soh Jaipil was 20, with Kim Ok-gyun being the oldest at 33.[35] All had spent some time in Japan; Pak Yung-hio had been part of a mission sent to Japan to apologize for the Imo incident in 1882.[29] He had been accompanied by Seo Gwang-beom and by Kim Ok-gyun, who later came under the influence of Japanese modernizers such as Fukuzawa Yukichi. Kim Ok-gyun, while studying in Japan, had also cultivated friendships with influential Japanese figures and became the de facto leader of the group.[35] They were also strongly nationalistic and desired to make their country truly independent by ending Chinese interference in Korea's internal affairs.[31]

The Sadaedang was a group of conservatives, which included not only Min Yeong-ik from the Min family but also other prominent Korean political figures that wanted to maintain power with China's help. Although the members of the Sadaedang supported the enlightenment policy, they favored gradual changes based on the Chinese model.[31] After the Imo incident, the Min clan pursued a pro-Chinese policy. This was also partly a matter of opportunism as the intervention by Chinese troops led to subsequent exile of the rival Daewongun in Tianjin and the expansion of Chinese influence in Korea, but it also reflected an ideological disposition shared by many Koreans toward the more comfortable and traditional relationship as a tributary of China.[35] Consequently, the Min clan became advocates of the dongdo seogi ("adopting Western knowledge while keeping Eastern values") philosophy, which had originated from the ideas of moderate Chinese reformers who had emphasized the need to maintain the perceived superior cultural values and heritage[15] of the Sino-centric world while recognizing the importance of acquiring and adopting Western technology, particularly military technology, in order to preserve autonomy. Hence, rather than major institutional reforms such as the adoption of new values such as legal equality or introducing modern education like in Meiji Japan, the advocates of this school of thought sought piecemeal adoptions of institutions that would strengthen the state while preserving the basic social, political, and cultural order.[35] Through the ascendancy of Queen Min to the throne, the Min clan had also been able to use newly created government institutions as bases for political power; subsequently with their growing monopoly of key positions they frustrated the ambitions of the Enlightenment Party.[35]

Gapsin Coup

In the two years preceding the Imo incident, the members of the Gaehwadang had failed to secure appointments to vital offices in the government and were unable to implement their reform plans.[36] As a consequence they were prepared to seize power by any means necessary. In 1884, an opportunity to seize power by staging a coup d'état against the Sadaedang presented itself. In August, as hostilities between France and China erupted over Annam, half of the Chinese troops stationed in Korea were withdrawn.[36] On December 4, 1884, with the help of Japanese minister Takezoe Shinichiro who promised to mobilize Japanese legation guards to provide assistance, the reformers staged their coup under the guise of a banquet hosted by Hong Yeong-sik, the director of the General Postal Administration. The banquet was to celebrate the opening of the new national post office.[36] King Gojong was expected to attend together with several foreign diplomats and high-ranking officials, most of whom were members of the pro-Chinese Sadaedang faction. Kim Ok-gyun and his comrades approached King Gojong falsely stating that Chinese troops had created a disturbance and escorted him to the small Gyoengu Palace, where they placed him in the custody of Japanese legation guards. They then proceeded to kill and wound several senior officials of the Sadaedang faction.[36]

After the coup, the Gaehwadang members formed a new government and devised a program of reform. The radical 14-point reform proposal stated that the following conditions be met: an end to Korea's tributary relationship with China; the abolition of ruling-class privilege and the establishment of equal rights for all; the reorganization of the government as virtually a constitutional monarchy; the revision of land tax laws; cancellation of the grain loan system; the unification of all internal fiscal administrations under the jurisdiction of the Ho-jo; the suppression of privileged merchants and the development of free commerce and trade, the creation of a modern police system including police patrols and royal guards; and severe punishment of corrupt officials.[36]

However, the new government lasted no longer than a few days.[36] This was possibly inevitable, as the reformers were supported by no more than 140 Japanese troops who faced at least 1,500 Chinese garrisoned in Seoul,[36] under the command of General Yuan Shikai. With the reform measures being a threat to her clan's power, Queen Min secretly requested military intervention from the Chinese. Consequently, within three days, even before the reform measures were made public, the coup was suppressed by Chinese troops who attacked and defeated the Japanese forces and restored power to the pro-Chinese Sadaedang faction.[36] During the ensuing melee Hong Yeong-sik was killed, the Japanese legation building was burned down and forty Japanese were killed. The surviving Korean coup leaders including Kim Ok-gyun escaped to the port of Chemulpo under escort of the Japanese minister Takezoe. From there they boarded a Japanese ship for exile in Japan.[37]

In January 1885, with a show of force the Japanese dispatched two battalions and seven warships to Korea,[38] which resulted in the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1885, signed on 9 January 1885. The treaty restored diplomatic relations between Japan and Korea. The Koreans also agreed to pay the Japanese ¥100,000 for damages to their legation[38] and to provide a site for the building of a new legation. Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi, in order to overcome Japan's disadvantageous position in Korea followed by the abortive coup, visited China to discuss the matter with his Chinese counterpart, Li Hongzhang. The two parties succeeded in concluding the Convention of Tianjin on May 31, 1885. They also pledged to withdraw their troops from Korea within four months, with prior notification to the other if troops were to be sent to Korea in the future.[38] After both countries withdrew their forces they left behind a precarious balance of power on the Korean Peninsula between the two nations.[38] Meanwhile, Yuan Shikai remained in Seoul, appointed as the Chinese Resident, and continued to interfere with Korean domestic politics.[38] The failure of the coup also marked a dramatic decline in Japanese influence over Korea.[39]

Nagasaki incident

The Nagasaki incident was a riot that took place in the Japanese port city of Nagasaki in 1886. Four warships from the Qing Empire's navy, the Beiyang Fleet, stopped at Nagasaki, apparently to carry out repairs. Some Chinese sailors caused trouble in the city and started the riot. Several Japanese policemen confronting the rioters were killed. The Qing government did not apologize after the incident, which resulted in a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment in Japan.[40]

Bean controversy

A poor harvest in 1889 led the governor of Korea's Hamgyong Province to prohibit soybean exports to Japan. Japan requested and received compensation in 1893 for their importers. The incident highlighted the growing dependence Japan felt on Korean food imports.[41]

Prelude to the war

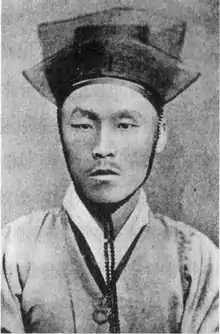

Kim Ok-gyun affair

On March 28, 1894, a pro-Japanese Korean revolutionary, Kim Ok-gyun, was assassinated in Shanghai. Kim had fled to Japan after his involvement in the 1884 coup, and the Japanese had turned down Korean demands for him to be extradited.[42] Many Japanese activists saw in him potential for a future role in Korean modernization; however, Meiji government leaders were more cautious. After some reservations, they exiled him to the Bonin (Ogasawara) Islands. Ultimately, he was lured to Shanghai, where he was killed by a Korean, Hong Jong-u, in his room at a Japanese inn in the International Settlement. After some hesitation, the British authorities in Shanghai concluded that rules against extradition did not apply to a corpse and turned his body over to Chinese authorities. His body was then taken aboard a Chinese warship and sent back to Korea, where it was cut up by the Korean authorities, quartered and displayed in all Korean provinces as a warning to other purported rebels and traitors.[42][43]

In Tokyo, the Japanese government took that as an outrageous affront.[42] Kim Ok-gyun's brutal murder was portrayed as a betrayal by Li Hongzhang and a setback for Japan's stature and dignity.[42] The Chinese authorities refused to press charges against the assassin, and he was even allowed to accompany Kim's mutilated body back to Korea, where he was showered with rewards and honors.[44] Kim's assassination had also called Japan's commitment to its Korean supporters into question. The police in Tokyo had foiled an earlier attempt during the same year to assassinate Pak Yung-hio, one of the other Korean leaders of the 1884 uprising. When two suspected Korean assassins received asylum at the Korean legation, that had instigated a diplomatic outrage as well.[44] Although the Japanese government could have immediately used Kim's assassination to its advantage, it concluded that since Kim had died on Chinese territory, the treatment of the corpse was outside its authority.[44] However, the shocking murder of the Korean inflamed Japanese opinion since many Japanese considered the Chinese-supported actions to be directed against Japan as well. To the Japanese, the Chinese had also showed their contempt for international law when they set free the suspected assassin, who had been arrested by British authorities in Shanghai and then, in accordance with treaty obligations, turned over to the Chinese for trial. Nationalistic groups immediately began to call for war with China.[44]

Donghak Rebellion

Tensions ran high between China and Japan, but war was not yet inevitable, and the fury in Japan over Kim's assassination began to dissipate. However, in late April, the Donghak Rebellion erupted in Korea. Korean peasants rose up in open rebellion against oppressive taxation and incompetent financial administration of the Joseon government. It was the largest peasant rebellion in Korean history.[45] However, on June 1, rumors reached the Donghaks that the Chinese and Japanese were on the verge of sending troops and so the rebels agreed to a ceasefire to remove any grounds for foreign intervention.[45]

On June 2, the Japanese cabinet decided to send troops to Korea if China did the same. In May, the Chinese had taken steps to prepare for the mobilization of their forces in the provinces of Zhili, Shandong and in Manchuria as a result of the tense situation on the Korean Peninsula.[46] However, those actions were planned more as an armed demonstration to strengthen the Chinese position in Korea than as preparation for war against Japan.[46] On June 3, King Gojong, on the recommendation of the Min clan and at the insistence of Yuan Shikai, requested aid from the Chinese government in suppressing the Donghak Rebellion. Although the rebellion was not as serious as it had initially seemed and so the Chinese forces were not necessary, the decision was made to send 2,500 men under the command of General Ye Zhichao to the harbor of Asan, about 70 km (43 mi) from Seoul. The troops destined for Korea sailed on board three British-owned steamers chartered by the Chinese government, arriving at Asan on June 9. On June 25, a further 400 troops had arrived. Consequently, by the end of June, Ye Zhichao had about 2,800-2,900 soldiers under his command at Asan.[46][47]

Closely watching the events on the peninsula, the Japanese government had quickly become convinced that the rebellion would lead to Chinese intervention in Korea. As a result, soon after learning of the Korean government's request for Chinese military help, all Japanese warships in the vicinity were immediately ordered to Pusan and Chemulpo.[46] By June 9, Japanese warships had consecutively called at Chemulpo and Pusan.[48] A formation of 420 sailors, selected from the crews of warships anchored in Chempulo, was immediately dispatched to Seoul, where they served as a temporary counterbalance to the Chinese troops camped at Asan.[49] Simultaneously, a reinforced brigade of approximately 8,000 troops (the Oshima Composite Brigade), under the command of General Ōshima Yoshimasa, was also dispatched to Chemulpo by June 27.[50]

According to the Japanese, the Chinese government had violated the Convention of Tientsin by not informing the Japanese government of its decision to send troops, but the Chinese claimed that Japan had approved the decision.[43] The Japanese countered by sending an expeditionary force to Korea. The first 400 troops arrived on June 9 en route to Seoul, and 3,000 landed at Incheon on June 12.[51]

However, Japanese officials denied any intention to intervene. As a result, the Qing viceroy Li Hongzhang "was lured into believing that Japan would not wage war, but the Japanese were fully prepared to act".[52] The Qing government turned down Japan's suggestion for Japan and China to co-operate to reform the Korean government. When Korea demanded that Japan withdraw its troops from Korea, the Japanese refused.

In July 1894, the 8,000 Japanese troops captured the Korean king Gojong and occupied the Gyeongbokgung in Seoul. By July 25, they had replaced the existing Korean government with members of the pro-Japanese faction.[51] Even though Qing forces were already leaving Korea after they found themselves unneeded there, the new pro-Japanese Korean government granted Japan the right to expel Qing forces, and Japan dispatched more troops to Korea. The Qing Empire rejected the new Korean government as illegitimate.

Status of the combatants

.jpg.webp)

Japan

Japanese reforms under the Meiji government gave significant priority to the creation of an effective modern national army and navy, especially naval construction. Japan sent numerous military officials abroad for training and evaluation of the relative strengths and tactics of Western armies and navies.

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy was modeled after the British Royal Navy,[53] at the time the foremost naval power. British advisors were sent to Japan to train the naval establishment, while Japanese students were in turn sent to Britain to study and observe the Royal Navy. Through drilling and tuition by Royal Navy instructors, Japan developed naval officers expert in the arts of gunnery and seamanship.[54] At the start of hostilities, the Imperial Japanese Navy was composed of a fleet of 12 modern warships, (the protected cruiser Izumi being added during the war), eight corvettes, one ironclad warship, 26 torpedo boats, and numerous auxiliary/armed merchant cruisers and converted liners. During peacetime, the warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy were divided among three main naval bases at Yokosuka, Kure and Sasebo and following mobilization, the navy was composed of five divisions of seagoing warships and three flotillas of torpedo boats with a fourth being formed at the beginning of hostilities.[55] The Japanese also had a relatively large merchant navy, which at the beginning of 1894 consisted of 288 vessels. Of these, 66 belonged to the Nippon Yusen Kaisha shipping company, which received national subsidies from the Japanese government to maintain the vessels for use by the navy in time of war. As a consequence, the navy could call on a sufficient number of auxiliaries and transports.[55]

Japan did not yet have the resources to acquire battleships and so planned to employ the Jeune École doctrine, which favoured small, fast warships, especially cruisers and torpedo boats, with the offensive capability to destroy larger craft. The Japanese naval leadership, on the eve of hostilities, was generally cautious and even apprehensive,[56] as the navy had not yet received the warships ordered in February 1893, particularly the battleships Fuji and Yashima and the protected cruiser Akashi.[57] Hence, initiating hostilities at the time was not ideal, and the navy was far less confident than the army about the outcome of a war with China.[56]

Many of Japan's major warships were built in British and French shipyards (eight British, three French and two Japanese-built) and 16 of the torpedo boats were known to have been built in France and assembled in Japan.

Imperial Japanese Army

The Meiji government at first modeled their army after the French Army. French advisers had been sent to Japan with two military missions (in 1872–1880 and 1884), in addition to one mission under the shogunate. Nationwide conscription was enforced in 1873 and a Western-style conscript army[58] was established; military schools and arsenals were also built. In 1886, Japan turned toward the German-Prussian model as the basis for its army,[58] adopting German doctrines and the German military system and organisation. In 1885 Jacob Meckel, a German adviser, implemented new measures, such as the reorganization of the command structure into divisions and regiments; the strengthening of army logistics, transportation, and structures (thereby increasing mobility); and the establishment of artillery and engineering regiments as independent commands. It was also an army that was equal to European armed forces in every respect.[58]

On the eve of the outbreak of the war with China all men between the ages of 17 and 40 years were eligible for conscription, but only those who turned 20 were to be drafted while those who had turned 17 could volunteer.[58] All men between the ages of 17 and 40, even those who had not received military training or were physically unfit, were considered part of the territorial militia or national guard (kokumin).[58] Following the period of active military service (gen-eki), which lasted for three years, the soldiers became part of the first Reserve (yōbi numbering 92,000 in 1893) and then the second Reserve (kōbi numbering 106,000 in 1893). All young and able-bodied men who did not receive basic military training due to exceptions and those conscripts who had not fully met the physical requirements of military service, became third Reserve (hojū).[58] In time of war, the first Reserve (yōbi) were to be called up first and they were intended to fill the ranks of the regular army units. Next to be called up were the kōbi reserve who were to be either used to further fill in the ranks of line units or to be formed into new ones. The hojū reserve members were to be called up only in exceptional circumstances, and the territorial militia or national guard would only be called up in case of an immediate enemy attack on or invasion of Japan.[58]

The country was divided into six military districts (headquarters Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Sendai, Hiroshima and Kumamoto), with each being a recruitment area for a square infantry division consisting of two brigades of two regiments.[58] Each of these divisions contained approximately 18,600 troops and 36 artillery pieces when mobilized.[59] There was also an Imperial Guard division which recruited nationally, from all around Japan. This division was also composed of two brigades but had instead two-battalion, not three-battalion, regiments; consequently its numerical strength after mobilization was 12,500 troops and 24 artillery pieces.[59] In addition, there were fortress troops consisting of approximately six battalions, the Colonial Corps of about 4,000 troops which was stationed on Hokkaido and the Ryukyu Islands, and a battalion of military police in each of the districts. In peacetime the regular army had a total of fewer than 70,000 men, while after mobilization the numbers rose to over 220,000.[59] Moreover, the army still had a trained reserve, which, following the mobilization of the first-line divisions, could be formed into reserve brigades. These reserve brigades each consisted of four battalions, a cavalry unit, a company of engineers, an artillery battery and rear-echelon units. They were to serve as recruiting bases for their front-line divisions and could also perform secondary combat operations, and if necessary they could be expanded into full divisions with a total of 24 territorial force regiments. However, formation of these units was hindered by a lack of sufficient amounts of equipment, especially uniforms.[59]

Japanese troops were equipped with the 8-mm single-shot Murata Type 18 breech-loading rifle. The improved eight-round-magazine Type 22 was just being introduced and consequently in 1894, on the eve of the war, only the Imperial Guard and 4th Division were equipped with these rifles. The division artillery consisted of 75-mm field guns and mountain pieces manufactured in Osaka. The artillery was based on Krupp designs that were adapted by the Italians at the beginning of the 1880s; although it could hardly be described as modern in 1894, in general it still matched contemporary battlefield requirements.[59]

By the 1890s, Japan had at its disposal a modern, professionally trained Western-style army which was relatively well equipped and supplied. Its officers had studied in Europe and were well educated in the latest strategy and tactics. By the start of the war, the Imperial Japanese Army could field a total force of 120,000 men in two armies and five divisions.

The Japanese army despite the integration of supply troops into its divisions was unable to rely on its pre-existing logistical system and personnel to sustain its armies in the field with 153,000 labourers, contractors, and drivers being contracted to sustain the armies in the field. Supply issues and a general lack of preparedness for a sustained war would routinely delay operations and slow down the Japanese field armies as seen in the Yingkou Campaign, troops often had to forage or steal from the local populace and medicine and winter clothing was often in short supply during the latter stages of the war.[60]

The Japanese Army also possessed a large amount of coastal guns at key locations which could be used for siege operations, these weapons were as follows:[61]

- 50 280-mm Howitzers

- 38 274-mm guns

- 45 240-mm guns

- 40 150-mm guns

- 42 120-mm guns

- various smaller pieces

China

The prevailing view in many Western circles was that the modernized Chinese military would crush the Japanese. Observers commended Chinese units such as the Huai Army and Beiyang Fleet.[nb 2] The German General Staff predicted a Japanese defeat and William Lang, who was a British advisor to the Chinese military, praised Chinese training, ships, guns, and fortifications, stating that "in the end, there is no doubt that Japan must be utterly crushed".[63]

Imperial Chinese Army

The Qing dynasty did not have a unified national army, but was made up of three main components, with the so-called Eight Banners forming the elite. The Eight Banners forces were segregated along ethnic lines into separate Manchu, Han Chinese, Mongol, Hui (Muslim) and other ethnic formations.[64] Bannermen who made up the Eight Banners got higher pay than the rest of the army while the Manchu received further privileges. In total, there were 250,000 soldiers in the Eight Banners, with over 60 percent kept in garrisons in Beijing, while the remaining 40 percent served as garrison troops in other major Chinese cities.[65] The Green Standard Army was a 600,000-strong gendarmerie-type force that was recruited from the majority Han Chinese population. Its soldiers were not given any peacetime basic military training, but were expected to fight in any conflict. The third component was an irregular force called the Braves, which were used as a kind of reserve force for the regular army, and which were usually recruited from the more distant or remote provinces of China. They were formed into very loosely organized units from the same province. The Braves were sometimes described as mercenaries, with their volunteers receiving as much military training as their commanders saw fit. With no fixed unit organization, it is impossible to know how many battle-ready Braves there actually were in 1894.[65] There were also a few other military formations, one of which was the Huai Army, which was under the personal authority of Li Hongzhang and was created originally to suppress the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864). The Huai Army had received limited training by Western military advisors;[65] numbering nearly 45,000 troops, it was considered the best-armed military unit in China.[66]

However, there is no definitive estimate for the size of the Qing armies in this war and scholarly estimates vary widely.

| Armies | Gawlikowski | Vladimir | Du Boulay[68] | Putyata | Olender[69] | Powell[70] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bannermen | Not given | 276,000 | 325,600 | 230,000 | 250,000

(100,000 actual) |

|

| Braves (yong ying) | 125,000 | 97,000 | 408,300* | 120,000 | ||

| Green Standard | Not given | ~600,000 | 357,150 | 1,000,000 (paper)

450,000-600,000 (actual) |

||

| Trained | 230,000-240,000 | 12,000 | 408,300* | 100,000 maximum | ||

| Militia | Not given | Manchurian army

175,000 (paper) 13,500 (actual) |

Not given | 1,025,000 | 300,000 maximum | |

| Total (paper) | 375,000 | 1,160,000 | 1,091,150 | 1,255,000 | 1,770,000 | |

| Total (actual) | 375,000 | 998,500 | less than

1,091,150 |

1,255,000 | 1,070,000-1,220,000 | 350,000 (fielded) |

*does not distinguish between the two armies.

The Japanese Imperial General Staff estimated that they would face no more than 350,000 effective Chinese soldiers. This corresponds well with the estimate of the Board of war from 1898 which states that the total of the provincial militia, Defense army (Yong ying), Disciplined army (modernised Green standard), and new-style forces (organised after the war) was approximately 360,000.[70] Du Boulay confirms this with the total army strength of the army in Zhili, Shandong and Manchuria amounting to 357,100 men (of which 125,030 were deemed as trained soldiers) and 280,000 trained men in the theatre of operations (Zhili, Shandong, and Manchuria ) and 400,000 total trained men in the empire.[68]

Due to various factors such as the limited transport capacity (the absence of any railway in the combat zone), provincial infighting and a general lack of capacity for accommodating soldiers, only a small portion of the army that could be fielded was actually deployed, even forces that were mobilised, including the strong Hunan forces of Liu Kunyi they were not able to arrive in time to make a meaningful difference. This meant that the fighting primarily fell on the forces already in Zhili, Shandong and Manchuria. This was a similar situation as what occurred in the Opium Wars, as the much larger Chinese army found itself outnumbered in those conflicts as it did this one.[70]

Chinese forces were also far behind the Japanese in terms of support services; there was a complete absence of engineers, quartermasters, transportation, signal and medical troops. Hired labour (coolies) often performed transportation duties and rudimentary engineering tasks, supply was organised by the province where the soldiers were fighting and left to civilian officials assigned as quartermasters and a few doctors were attached to the army at the rear. This lack of adequate supply organisation led to some units receiving the wrong ammunition for their rifles (on the presumption they possessed rifles).[70]

The basic tactical unit of the Chinese army was the battalion (ying), composed on paper of 500 men, though in reality actual strength was 350 for the infantry and 250 for the cavalry. Up to a dozen of these Ying would form an independent corps, and only at a corps level did Chinese units receive artillery.[50]

Although the Chinese had established arsenals to produce firearms, and a large number of them had been imported from abroad, 40 percent of Chinese troops at the outbreak of the war were not issued with rifles or even muskets.[71] Instead they were armed with a variety of swords, spears, pikes, halberds, and bows and arrows.[71] Against well-trained, well-armed, and disciplined Japanese troops, they would have little chance. Those units that did have firearms were equipped with a heterogeneity of weapons, from a variety of modern rifles to old-fashioned muskets; this lack of standardization led to a major problem with the proper supply of ammunition.[72]

Chinese troops were often not drilled in how to use their guns with training conducted with spears and when guns were utilised in training the officer corps resistant to modern training practice would conduct it at a distance of 50 ft. There was also a lack of discipline within the army as troops would routinely flee before, during, or after combat as occurred in the Battle of Pyongyang.[73]

The Imperial Chinese Army in 1894 was a heterogeneous mixture of modernized, partly modernized, and almost medieval units which no commander could have led successfully, resulting in poor leadership among Chinese officers.[74] Chinese officers did not know how to handle their troops and the older, higher-ranking officers still believed that they could fight a war as they had during the Taiping Rebellion of 1850–1864.[75] This was also the result of the Chinese military forces being divided into largely independent regional commands. The soldiers were drawn from diverse provinces that had no affinity with each other.[76] Chinese troops also suffered from poor morale, largely because many of the troops had not been paid for a long time.[75] The low prestige of soldiers in Chinese society also hindered morale, and the use of opium and other narcotics was rife throughout the army.[75] Low morale and poor leadership seriously reduced the effectiveness of Chinese troops, and contributed to defeats such as the abandonment of the very well-fortified and defensible Weihaiwei. Additionally, military logistics were lacking, as the construction of railroads in Manchuria had been discouraged. Huai Army troops, although they were a small minority in the overall Imperial Chinese Army, were to take part in the majority of the fighting during the war.[65]

Beiyang Fleet

The Beiyang Fleet was one of the four modernised Chinese navies in the late Qing dynasty. The navies were heavily sponsored by Li Hongzhang, the Viceroy of Zhili who had also created the Huai Army. The Beiyang Fleet was the dominant navy in East Asia before the First Sino-Japanese War. The Japanese themselves were apprehensive about facing the Chinese fleet, especially the two German-built battleships – Dingyuan and Zhenyuan – to which the Japanese had no comparable counterparts.[56] However, China's advantages were more apparent than real as most of the Chinese warships were over-age and obsolescent;[56] the ships were also not maintained properly and indiscipline was common among their crews.[77] The greater armor of major Chinese warships and the greater weight of broadside they could fire were more than offset by the number of quick-firing guns on most first-line Japanese warships, which gave the Japanese the edge in any sustained exchange of salvos.[56] The worst feature of both Chinese battleships was actually their main armament; each was armed with short-barreled guns in twin barbettes mounted in echelon which could fire only in restricted arcs. The short barrels of the Chinese main armament meant that the shells had a low muzzle velocity and poor penetration, and their accuracy was also poor at long ranges.[78]

Tactically, Chinese naval vessels entered the war with only the crudest set of instructions – ships that were assigned to designated pairs were to keep together and all ships were to fight end-on, as far forward from the beam as possible, a tactic dictated by the obsolescent arrangement of guns aboard Chinese warships.[78] The only vague resemblance of a fleet tactic was that all ships were to follow the visible movements of the flagship, an arrangement made necessary because the signal book used by the Chinese was written in English, a language with which few officers in the Beiyang Fleet had any familiarity.[78]

When it was first developed by Empress Dowager Cixi in 1888, the Beiyang Fleet was said to be the strongest navy in East Asia. Before her adopted son, Emperor Guangxu, took over the throne in 1889, Cixi wrote out explicit orders that the navy should continue to develop and expand gradually.[79] However, after Cixi went into retirement, all naval and military development came to a drastic halt. Japan's victories over China has often been falsely rumored to be the fault of Cixi.[80] Many believed that Cixi was the cause of the navy's defeat because Cixi embezzled funds from the navy in order to build the Summer Palace in Beijing. However, extensive research by Chinese historians revealed that Cixi was not the cause of the Chinese navy's decline. In actuality, China's defeat was caused by Emperor Guangxu's lack of interest in developing and maintaining the military.[79] His close adviser, Grand Tutor Weng Tonghe, advised Guangxu to cut all funding to the navy and army, because he did not see Japan as a true threat, and there were several natural disasters during the early 1890s which the emperor thought to be more pressing to expend funds on.[79]

The total strength of the entire Imperial Chinese navy was:[81]

- 2 battleships

- 1 coastal battleship (often labelled as an armoured cruiser)

- 5 unprotected cruisers

- 5 protected cruisers

- 1 auxiliary cruiser

- 7 small cruisers

- 4 torpedo gunboats

- 34 gunboats

- 28 small gunboats

- 30 torpedo boats

- 9 armed transports

| Beiyang Fleet |

Major combatants |

|---|---|

| Ironclad battleships | Dingyuan (flagship), Zhenyuan |

| Armoured cruisers | King Yuen, Laiyuan |

| Protected cruisers | Chih Yuen, Ching Yuen |

| Cruisers | Torpedo cruisers – Tsi Yuen, Kuang Ping/Kwang Ping, Chaoyong, Yangwei |

| Coastal warship | Pingyuan |

| Corvette | Kwan Chia |

| Other vessels | Approximately 13 torpedo boats; numerous gunboats and chartered merchant ships |

Contemporaneous wars waged by the Qing Empire

While the Qing Empire was fighting the First Sino-Japanese War, it was also simultaneously engaging rebels in the Dungan Revolt in northwestern China, where thousands lost their lives. The generals Dong Fuxiang, Ma Anliang and Ma Haiyan were initially summoned by the Qing government to bring the Hui troops under their command to participate in the First Sino-Japanese War, but they were eventually sent to suppress the Dungan Revolt instead.

Early stages

1 June 1894: The Donghak Rebel Army moves toward Seoul. The Korean government requests help from the Qing government to suppress the revolt.

6 June 1894: About 2,465 Chinese soldiers are transported to Korea to suppress the Donghak Rebellion. Japan asserts that it was not notified and thus China has violated the Convention of Tientsin, which requires that China and Japan must notify each other before intervening in Korea. China asserts that Japan was notified and approved of Chinese intervention.

8 June 1894: First of about 4,000 Japanese soldiers and 500 marines land at Chemulpo.

11 June 1894: Ceasefire during the Donghak Rebellion.

13 June 1894: The Japanese government telegraphs the commander of the Japanese forces in Korea, Ōtori Keisuke, to remain in Korea for as long as possible despite the end of the rebellion.

16 June 1894: Japanese foreign minister Mutsu Munemitsu meets with Wang Fengzao, the Qing ambassador to Japan, to discuss the future status of Korea. Wang states that the Qing government intends to pull out of Korea after the rebellion has been suppressed and expects Japan to do the same. However, China retains a resident to look after Chinese primacy in Korea.

22 June 1894: Additional Japanese troops arrive in Korea. Japanese prime minister Itō Hirobumi tells Matsukata Masayoshi that since the Qing Empire appear to be making military preparations, there is probably "no policy but to go to war". Mutsu tells Ōtori to press the Korean government on the Japanese demands.

26 June 1894: Ōtori presents a set of reform proposals to the Korean king Gojong. Gojong's government rejects the proposals and instead insists on troop withdrawals.

7 July 1894: Failure of mediation between China and Japan arranged by the British ambassador to China.

19 July 1894: Establishment of the Japanese Combined Fleet, consisting of almost all vessels in the Imperial Japanese Navy. Mutsu cables Ōtori to take any necessary steps to compel the Korean government to carry out a reform program.

23 July 1894: Japanese troops occupy Seoul, capture Gojong, and establish a new, pro-Japanese government, which terminates all Sino-Korean treaties and grants the Imperial Japanese Army the right to expel the Qing Empire's Beiyang Army from Korea.

25 July 1894: First battle of the war: the Battle of Pungdo / Hoto-oki kaisen

Events during the war

Opening troop movements

By July 1894, Chinese forces in Korea numbered 3,000–3,500 and they were outnumbered by Japanese troops. They could only be supplied by sea through Asan Bay. The Japanese objective was first to blockade the Chinese at Asan and then encircle them with their land forces. Japan's initial strategy was to gain command of the sea, which was critical to its operations in Korea.[82] Command of the sea would allow Japan to transport troops to the mainland. The army's Fifth Division would land at Chemulpo on the western coast of Korea, both to engage and push Chinese forces northwest up the peninsula and to draw the Beiyang Fleet into the Yellow Sea, where it would be engaged in decisive battle. Depending on the outcome of this engagement, Japan would make one of three choices. If the Combined Fleet were to win decisively, the larger part of the Japanese army would undertake immediate landings on the coast between Shan-hai-kuan and Tientsin in order to defeat the Chinese army and bring the war to a swift conclusion. If the engagement were to be a draw and neither side gained control of the sea, the army would concentrate on the occupation of Korea. Lastly, if the Combined Fleet was defeated and consequently lost command of the sea, the bulk of the army would remain in Japan and prepare to repel a Chinese invasion, while the Fifth Division in Korea would be ordered to hang on and fight a rearguard action.[83]

Sinking of the Kow-shing

On 25 July 1894, the cruisers Yoshino, Naniwa and Akitsushima of the Japanese flying squadron, which had been patrolling off Asan Bay, encountered the Chinese cruiser Tsi-yuan and gunboat Kwang-yi.[83] These vessels had steamed out of Asan to meet the transport Kow-shing, escorted by the Chinese gunboat Tsao-kiang. After an hour-long engagement, the Tsi-yuan escaped while the Kwang-yi grounded on rocks, where its powder magazine exploded.

The Kow-shing was a 2,134-ton British merchant vessel owned by the Indochina Steam Navigation Company of London, commanded by Captain T. R. Galsworthy and crewed by 64 men. The ship was chartered by the Qing government to ferry troops to Korea, and was on her way to reinforce Asan with 1,100 troops plus supplies and equipment. A German artillery officer, Major von Hanneken, advisor to the Chinese, was also aboard. The ship was due to arrive on 25 July.

The Japanese cruiser Naniwa, under Captain Tōgō Heihachirō, intercepted the Kow-shing and captured its escort. The Japanese then ordered the Kow-shing to follow Naniwa and directed that Europeans be transferred to Naniwa. However, the 1,100 Chinese on board, desperate to return to Taku, threatened to kill the English captain, Galsworthy, and his crew. After four hours of negotiations, Captain Togo gave the order to fire upon the vessel. A torpedo missed, but a subsequent broadside hit the Kow Shing, which started to sink.

In the confusion, some of the Europeans escaped overboard, only to be fired upon by the Chinese.[84] The Japanese rescued three of the British crew (the captain, first officer and quartermaster) and 50 Chinese, and took them to Japan. The sinking of the Kow-shing almost caused a diplomatic incident between Japan and Great Britain, but the action was ruled in conformity with international law regarding the treatment of mutineers (the Chinese troops). Many observers considered the troops lost on board the Kow-shing to have been the best the Chinese had.[84]

The German gunboat Iltis rescued 150 Chinese, the French gunboat Le Lion rescued 43, and the British cruiser HMS Porpoise rescued an unknown number.[85]

Conflict in Korea

Commissioned by the new pro-Japanese Korean government to forcibly expel Chinese forces, on July 25 Major-General Ōshima Yoshimasa led a mixed brigade numbering about 4,000 on a rapid forced march from Seoul south toward Asan Bay to face Chinese troops garrisoned at Seonghwan Station east of Asan and Kongju.

The Chinese forces stationed near Seonghwan under the command of General Ye Zhichao numbered about 3,880 men. They had anticipated the impending arrival of the Japanese by fortifying their position with trenches, earthworks including six redoubts protected by abatis and by the flooding of surrounding rice fields.[86] But expected Chinese reinforcements had been lost on board the British-chartered transport Kowshing.[87] Units of the Chinese main force were deployed east and northeast of Asan, near the main road leading to Seoul; the key positions held by the Chinese were the towns of Seonghwan and Cheonan. Approximately 3,000 troops were stationed at Seonghwan, while 1,000 men along with General Ye Zhichao were at headquarters at Cheonan. The remaining Chinese troops were stationed in Asan itself.[88] The Chinese had been preparing for a pincer movement against the Korean capital by massing troops at Pyongyang in the north and Asan in the south.[89]

On the morning of 27–28 July 1894, the two forces met just outside Asan in an engagement that lasted till 07:30 the next morning. The battle began with a diversionary attack by Japanese troops, followed by the main attack which quickly outflanked the Chinese defences. The Chinese troops, witnessing that they were being outflanked, left their defensive positions and fled towards the direction of Asan. The Chinese gradually lost ground to the superior Japanese numbers, and finally broke and fled towards Pyongyang abandoning arms, ammunition and all their artillery.[90] The Japanese took the city of Asan on July 29, breaking the Chinese encirclement of Seoul.[86] The Chinese suffered 500 killed and wounded while the Japanese suffered 88 casualties.[91]

Declaration of War

On 1 August 1894, war was officially declared between China and Japan. The rationale, language and tone given by the rulers of both nations in their respective declarations of war were being markedly different.

The tenor of the Japanese declaration of war, issued in the name of the Meiji Emperor, appears to have had at least one eye fixed on the wider international community using phrases such as 'Family of Nations', the 'Law of Nations' and making additional references to international treaties. This was in sharp contrast to the Chinese approach to foreign relations which historically was noted for refusing to treat with other nations on an equal diplomatic footing, and instead insistent on such foreign powers paying tribute to the Chinese Emperor as vassals. In keeping with the traditional Chinese approach to its neighbours, the Chinese declaration of war stated the palpable disdain for the Japanese can be surmised from the repeated use of the term Wojen which translates to 'dwarf',[92] an ancient intentionally offensive and highly derogative term for the Japanese.[92]

This use of the pejorative to describe a foreign nation was not unusual for Chinese official documents of the time – so much so that a major bone of contention between Imperial China and the Treaty Powers of the day had previously been the habitual use of the Chinese character 夷 ('Yi'...which literally meant 'barbarian'), to refer to those termed otherwise as 'Foreign Devils' typically describing those powers occupying the Treaty Ports. The use of the term 'Yi' (夷) by Chinese Imperial officials had in fact been considered so provocative by the Treaty Powers that the collective bundle of accords known as the Treaty of Tientsin negotiated in 1858 to end the Second Opium War explicitly proscribed the Chinese Imperial Court from using the term 'Yi' to refer to officials, subjects, or citizens of the belligerent powers, the signatories seemingly feeling it necessary to extract this specific demand from the Xianfeng Emperor's representatives.[93] In the thirty-five years elapsing since the Treaty of Tientsin, however, the language of the Chinese Emperors would appear to change little with regards to its neighbor Japan.

After the Declarations

By 4 August, the remaining Chinese forces in Korea retreated to the northern city of Pyongyang, where they were met by troops sent from China. The 13,000–15,000 defenders made defensive repairs to the city, hoping to check the Japanese advance.

On 15 September, the Imperial Japanese Army converged on the city of Pyongyang from several directions. The Japanese assaulted the city and eventually defeated the Chinese by an attack from the rear; the defenders surrendered. Taking advantage of heavy rainfall overnight, the remaining Chinese troops escaped Pyongyang and headed northeast toward the coastal city of Uiju. In the early morning of 16 September, the entire Japanese army entered Pyongyang.

Qing Hui Muslim general Zuo Baogui, from Shandong province, died in action in Pyongyang from Japanese artillery in 1894 while securing the city. A memorial to him was constructed.[94]

Defeat of the Beiyang fleet

In early September, Li Hongzhang decided to reinforce the Chinese forces at Pyongyang by employing the Beiyang fleet to escort transports to the mouth of the Taedong River.[95] About 4,500 additional troops stationed in the Zhili were to be redeployed. On September 12, half of the troops embarked at Dagu on five specially chartered transports and headed to Dalian where two days later on September 14, they were joined by another 2,000 soldiers. Initially, Admiral Ding wanted to send the transports under a light escort with only a few ships, while the main force of the Beiyang Fleet would locate and operate directly against the Combined Fleet in order to prevent the Japanese from intercepting the convoy.[95] But the appearance of the Japanese cruisers Yoshino and Naniwa on a reconnaissance sortie near Weihaiwei thwarted these plans.[95] The Chinese had mistaken them for the main Japanese fleet. Consequently, on September 12, the entire Beiyang Fleet departed Dalian heading for Weihaiwei, arriving near the Shandong Peninsula the next day. The Chinese warships spent the entire day cruising the area, waiting for the Japanese. However, since there was no sighting of the Japanese fleet, Admiral Ding decided to return to Dalian, reaching the port in the morning of September 15.[95] As Japanese troops moved north to attack Pyongyang, Admiral Ito correctly guessed that the Chinese would attempt to reinforce their army in Korea by sea. On 14 September, the Combined Fleet steamed northwards to search the Korean and Chinese coasts in order to bring the Beiyang Fleet to battle.[96]

The Japanese victory at Pyongyang had succeeded in pushing Chinese troops north to the Yalu River, in the process removing all effective Chinese military presence on the Korean Peninsula.[97] Shortly before the convoy's departure, Admiral Ding received a message concerning the battle at Pyongyang informing him about the defeat. Subsequently, it made the redeployment of the troops to the mouth of the Taedong river unnecessary.[95] Admiral Ding then correctly assumed that the next Chinese line of defence would be established on the Yalu River, and decided to redeploy the embarked soldiers there.[95] On September 16, the convoy of five transport ships departed from Dalian Bay under escort from the vessels of the Beiyang Fleet which included the two ironclad battleships Dingyuan and Zhenyuan.[95] Reaching the mouth of the Yalu River, the transports disembarked the troops, and the landing operation lasted until the following morning.

On September 17, 1894, the Japanese Combined Fleet encountered the Chinese Beiyang Fleet off the mouth of the Yalu River. The naval battle, which lasted from late morning to dusk, resulted in a Japanese victory.[96] Although the Chinese were able to land 4,500 troops near the Yalu River by sunset the Beiyang fleet was near the point of total collapse – most of the fleet had fled or had been sunk and the two largest ships Dingyuan and Zhenyuan were nearly out of ammunition.[98] The Imperial Japanese Navy destroyed eight of the ten Chinese warships, assuring Japan's command of the Yellow Sea. The principal factor in the Japanese victory was its superiority in speed and firepower.[99] The victory shattered the morale of the Chinese naval forces.[100] The Battle of the Yalu River was the largest naval engagement of the war and was a major propaganda victory for Japan.[101][102]

Invasion of Manchuria

With the defeat at Pyongyang, the Chinese abandoned northern Korea and took up defensive positions in fortifications along their side of the Yalu River near Jiuliancheng. After receiving reinforcements by 10 October, the Japanese quickly pushed north toward Manchuria.

On the night of 24 October 1894, the Japanese successfully crossed the Yalu River, undetected, by erecting a pontoon bridge. The following afternoon of 25 October at 17:00, they assaulted the outpost of Hushan, east of Jiuliancheng. At 20:30 the defenders deserted their positions and by the next day they were in full retreat from Jiuliancheng.

With the capture of Jiuliancheng, General Yamagata's 1st Army Corps occupied the nearby city of Dandong, while to the north, elements of the retreating Beiyang Army set fire to the city of Fengcheng. The Japanese had established a firm foothold on Chinese territory with the loss of only four killed and 140 wounded.

The Japanese 1st Army Corps then split into two groups with General Nozu Michitsura's 5th Provincial Division advancing toward the city of Mukden (present-day Shenyang) and Lieutenant-General Katsura Tarō's 3rd Provincial Division pursuing fleeing Chinese forces west toward the Liaodong Peninsula.

By December, the 3rd Provincial Division had captured the towns of Tatungkau, Takushan, Xiuyan, Tomucheng, Haicheng and Kangwaseh. The 5th Provincial Division marched during a severe Manchurian winter towards Mukden.

The Japanese 2nd Army Corps under Ōyama Iwao landed on the south coast of Liaodong Peninsula on 24 October and quickly moved to capture Jinzhou and Dalian Bay on 6–7 November. The Japanese laid siege to the strategic port of Lüshunkou (Port Arthur).

Fall of Lüshunkou

By 21 November 1894, the Japanese had taken the city of Lüshunkou (Port Arthur) with minimal resistance and suffering minimal casualties. Describing their motives as having encountered a display of the mutilated remains of Japanese soldiers as they invaded the town, Japanese forces proceeded with the unrestrained killing of civilians during the Port Arthur Massacre with unconfirmed estimates in the thousands. This event was at the time widely viewed with skepticism, as the world at large was still in disbelief that the Japanese were capable of such deeds – it seemed more likely to have been exaggerated propagandist fabrications of a Chinese government to discredit Japanese hegemony. In reality, the Chinese government itself was unsure how to react and initially denied the occurrence of the loss of Port Arthur to the Japanese altogether.

As we entered the town of Port Arthur, we saw the head of a Japanese soldier displayed on a wooden stake. This filled us with rage and a desire to crush any Chinese soldier. Anyone we saw in the town, we killed. The streets were filled with corpses, so many they blocked our way. We killed people in their homes; by and large, there wasn't a single house without from three to six dead. Blood was flowing and the smell was awful. We sent out search parties. We shot some, hacked at others. The Chinese troops just dropped their arms and fled. Firing and slashing, it was unbounded joy. At this time, our artillery troops were at the rear, giving three cheers [banzai] for the emperor.

— Makio Okabe, diary[103]

By 10 December 1894, Kaipeng (present-day Gaizhou) fell to the Japanese 1st Army Corps.

Fall of Weihaiwei

The Chinese fleet subsequently retreated behind the Weihaiwei fortifications. However, it was then surprised by Japanese ground forces, who outflanked the harbor's defenses in coordination with the navy.[104] The Battle of Weihaiwei was a 23-day siege with the major land and naval engagements taking place between 20 January and 12 February 1895. Historian Jonathan Spence notes that "the Chinese admiral retired his fleet behind a protective curtain of contact mines and took no further part in the fighting."[105] The Japanese commander marched his forces over the Shandong peninsula and reached the landward side of Weihaiwei, where the siege was eventually successful for the Japanese.[105]

After Weihaiwei's fall on 12 February 1895, and an easing of harsh winter conditions, Japanese troops pressed further into southern Manchuria and northern China. By March 1895 the Japanese had fortified posts that commanded the sea approaches to Beijing. Although this would be the last major battle fought, numerous skirmishes would follow. The Battle of Yingkou was fought outside the port town of Yingkou, Manchuria, on 5 March 1895.

Occupation of the Pescadores Islands

Even before the peace negotiations were set to begin at Shimonoseki, the Japanese had begun preparations for the capture of Taiwan. However, the first operation would be directed not against the island itself, but against the Pescadores Islands, which due to their strategic position off the west coast would become a stepping stone for further operations against the island.[106] On March 6, a Japanese expeditionary force consisting of a reinforced infantry regiment with 2,800 troops and an artillery battery were embarked on five transports, and sailed from Ujina to Sasebo, arriving there three days later.[106] On March 15, the five transports, escorted by seven cruisers and five torpedo boats of the 4th Flotilla, left Sasebo heading south. The Japanese fleet arrived at the Pescadores during the night of March 20, but encountered stormy weather. Due to the poor weather, the landings were postponed until March 23, when the weather cleared.[107]

On the morning March 23, the Japanese warships began the bombardment of the Chinese positions around the port of Lizhangjiao. A fort guarding the harbor was quickly silenced. At about midday, the Japanese troops began their landing. Unexpectedly, when the landing operation was underway, the guns of the fort once again opened fire, which caused some confusion among the Japanese troops. But they were soon silenced again after being shelled by the Japanese cruisers.[107] By 14:00, Lizhangjiao was under Japanese control. After reinforcing the captured positions, the following morning, Japanese troops marched on the main town of Magong. The Chinese offered token resistance and after a short skirmish they abandoned their positions, retreating to nearby Xiyu Island. At 11:30, the Japanese entered Magong, but as soon as they had taken the coastal forts in the town, they were fired upon by the Chinese coastal battery on Xiyu Island. The barrage went unanswered until nightfall, as the Chinese had destroyed all the guns at Magong before they retreated, and Japanese warships feared entering the strait between the Penghu and Xiyu Islands due to the potential threat posed by mines. However, it caused no serious casualties among the Japanese forces. During the night, a small naval gunnery crew of 30 managed to make one of the guns of the Magong coastal battery operational. At dawn, the gun began shelling the Chinese positions on Xiyu, but the Chinese guns did not respond. Subsequently, the Japanese crossed the narrow strait, reaching Xiyu, discovering that the Chinese troops had abandoned their positions during the night and escaped on board local vessels.[107]

The Japanese warships entered the strait the next day and, upon discovering that there were no mine fields, they entered Magong harbor. By March 26, all the islands of the archipelago were under Japanese control, and Rear Admiral Tanaka Tsunatsune was appointed governor. During the campaign the Japanese lost 28 killed and wounded, while the Chinese losses were almost 350 killed or wounded and nearly 1,000 taken prisoner.[107] This operation effectively prevented Chinese forces in Taiwan from being reinforced, and allowed the Japanese to press their demand for the cession of Taiwan in the peace negotiations.

End of the war

Treaty of Shimonoseki

The Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed on 17 April 1895. China recognized the total independence of Korea and ceded the Liaodong Peninsula, Taiwan, and the Penghu Islands to Japan "in perpetuity".[108] The disputed islands known as "Senkaku/Diaoyu" islands were not named by this treaty, but Japan annexed these uninhabited islands to Okinawa Prefecture in 1895. Japan asserts this move was taken independently of the treaty ending the war, and China asserts that they were implied as part of the cession of Taiwan.

Additionally, China was to pay Japan 200 million taels (8,000,000 kg/17,600,000 lb) of silver as war reparations. The Qing government also signed a commercial treaty permitting Japanese ships to operate on the Yangtze River, to operate manufacturing factories in treaty ports and to open four more ports to foreign trade. Russia, Germany and France in a few days made the Triple Intervention, however, and forced Japan to give up the Liaodong Peninsula in exchange for another 30 million taels of silver (equivalent to about 450 million yen).