Igor Stravinsky | |

|---|---|

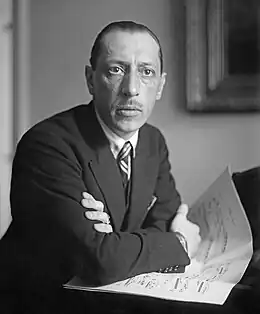

Stravinsky in the early 1920s | |

| Born | 17 June 1882 Oranienbaum, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Died | 6 April 1971 (aged 88) New York City, US |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky[lower-alpha 1] (17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship (from 1934) and United States citizenship (from 1945). He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century and a pivotal figure in modernist music.

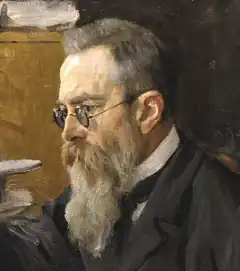

Stravinsky's father was an established bass opera singer, and Stravinsky grew up taking piano and music theory lessons. While studying law at the University of Saint Petersburg, he met Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and studied under him until Rimsky-Korsakov's death in 1908. Stravinsky met the impresario Sergei Diaghilev soon after, who commissioned Stravinsky to write three ballets: The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911), and The Rite of Spring (1913), the last of which brought him international fame after the near-riot at the premiere, and changed the way composers understood rhythmic structure.

Stravinsky's compositional career is divided into three periods: his Russian period (1913–1920), his neoclassical period (1920–1951), and his serial period (1954–1968). Stravinsky's Russian period was characterised by influence from Russian styles and folklore. Renard (1916) and Les noces (1923) were based on Russian folk poetry, and works like L'Histoire du soldat blended these folktales with popular musical structures, like the tango, waltz, rag, and chorale. His neoclassical period exhibited themes and techniques from the classical period, like the use of the sonata form in his Octet (1923) and use of Greek mythological themes in works like Apollon musagète (1927), Oedipus rex (1927), and Persephone (1935). In his serial period, Stravinsky turned towards compositional techniques from the Second Viennese School like Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique. In Memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954) was the first of his compositions to be fully based on the technique, and Canticum Sacrum (1956) was his first to be based on a tone row. Stravinsky's last major work was the Requiem Canticles (1966), which was performed at his funeral.

While some composers and academics of the time disliked the avant-garde nature of Stravinsky's music, particularly The Rite of Spring, later writers recognized his importance to the development of modernist music. Stravinsky's revolutions of rhythm and modernism influenced composers like Aaron Copland, Philip Glass, Béla Bartók, and Pierre Boulez, all of whom "felt impelled to face the challenges set by [The Rite of Spring]," as George Benjamin wrote in The Guardian.[1] In 1998, Time magazine named Stravinsky one of the 100 most influential people of the century. Stravinsky died of pulmonary edema on 6 April 1971 in New York City.

Biography

Early life, 1882–1901

Stravinsky was born on 17 June 1882 in the town of Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov), on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland, 25 mi (40 km) west of Saint Petersburg.[2][3] His father, Fyodor Ignatievich Stravinsky, was an established bass opera singer in the Kiev Opera and the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg and his mother, Anna Kirillovna Stravinskaya (née Kholodovskaya; 1854–1939), a native of Kiev, was one of four daughters of a high-ranking official in the Kiev Ministry of Estates. Igor was the third of their four sons; his brothers were Roman, Yury, and Gury.[4] The Stravinsky family was of Polish and Russian heritage,[5] descended "from a long line of Polish grandees, senators and landowners".[6] It is traceable to the 17th and 18th centuries to the bearers of the Sulima and Strawiński coat of arms. The original family surname was Sulima-Strawiński; the name "Stravinsky" originated from the word "Strava", one of the variants of the Streva river in Lithuania.[7][8]

On 10 August 1882, Stravinsky was baptised at Nikolsky Cathedral in Saint Petersburg.[4] Stravinsky's first school was the Second Saint Petersburg Gymnasium, where he stayed until his mid-teens. Then, he moved to Gourevitch Gymnasium, a private school, where he studied history, mathematics, and languages (Latin, Greek, French, German, Slavonic, and his native Russian).[9] Stravinsky expressed his general distaste for schooling and recalled being a lonely pupil: "I never came across anyone who had any real attraction for me."[10]

At around eight years old, he attended a performance of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky Theatre, which began a lifelong interest in ballets and Tchaikovsky.[11] Stravinsky took to music at an early age and began regular piano lessons at age nine, followed by tuition in music theory and composition.[12] By age fourteen, Stravinsky mastered Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto No. 1, and at age fifteen finished a piano reduction of a string quartet by Alexander Glazunov, who reportedly considered Stravinsky unmusical and thought little of his skills.[11]

Education and first compositions, 1901–1909

Despite Stravinsky's enthusiasm and ability in music, his parents expected him to study law. In 1901, he enrolled at the University of Saint Petersburg, studying criminal law and legal philosophy, but attendance at lectures was optional and he estimated that he turned up to fewer than fifty classes in his four years of study.[13]

In 1902, Stravinsky met Vladimir Rimsky-Korsakov, a fellow student at the University of Saint Petersburg and the youngest son of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Nikolai at that time was arguably the leading Russian composer, and he was a professor at Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Stravinsky wished to meet him to discuss his musical aspirations. He spent the summer of 1902 with Rimsky-Korsakov and his family in Heidelberg, Germany. Rimsky-Korsakov suggested to Stravinsky that he should not enter the Saint Petersburg Conservatory but continue private lessons in theory.[14]

By the time of his father's death in 1902, Stravinsky was spending more time studying music than law.[13] His decision to pursue music full time was helped when the university was closed for two months in 1905 in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, which prevented him from taking his final law exams.[15] In April 1906, Stravinsky received a half-course diploma and concentrated on music thereafter.[16] In 1905, he had begun studying with Rimsky-Korsakov twice a week and came to regard him as a second father.[13] These lessons continued until Rimsky-Korsakov's death in 1908.[17] Stravinsky completed his first composition during this time, the Symphony in E-flat, catalogued as Opus 1. In 1908, soon after Rimsky-Korsakov's death, Stravinsky composed Funeral Song, Op. 5, which was performed once and then considered lost until its re-discovery in 2015.[18]

In August 1905, Stravinsky became engaged to his first cousin, Yekaterina Gavrilovna Nosenko. In spite of the Orthodox Church's opposition to marriage between first cousins, the couple married on 23 January 1906.[19][20] They lived in the family's residence at 66 Krukov Canal in Saint Petersburg before they moved into a new home in Ustilug, which Stravinsky designed and built, chosen because Stravinsky had spent many summers there as a child with his father-in-law.[21][19][22] Stravinsky worked on many of his early compositions there, including Funeral Song, the revision of Feu d'artifice, The Nightingale, and some parts of The Rite of Spring.[23][24] It is now a museum with documents, letters, and photographs on display, and an annual Stravinsky Festival takes place in the nearby town of Lutsk.[25][26] The couple had two children, Fyodor and Ludmila, who were born in 1907 and 1908, respectively.[22]

Ballets for Diaghilev and international fame, 1909–1920

By 1909, Stravinsky had composed two more pieces, Scherzo fantastique, Op. 3, and Feu d'artifice (Fireworks), Op. 4. In February of that year, both were performed in Saint Petersburg at a concert that marked a turning point in Stravinsky's career. In the audience was Sergei Diaghilev, a Russian impresario and owner of the Ballets Russes who was struck with Stravinsky's compositions. He commissioned Stravinsky to write some orchestrations for the 1909 ballet season, which were finished by April of that year. While planning for the 1910 ballet season, Diaghilev wished to stage a new ballet from fresh talent that was based on the Russian fairytale of the Firebird. After Anatoly Lyadov was given the task of composing the score, he informed Diaghilev that he needed about one year to complete it. Diaghilev then asked the 28-year-old Stravinsky, who had already begun work on the score in anticipation of the commission.[27] At about 50 minutes in length, The Firebird was revised by Stravinsky into concert suites in 1919 and 1945.[28]

The Firebird premiered at the Opera de Paris on 25 June 1910 to widespread critical acclaim and Stravinsky became an overnight sensation.[29][30] As his wife was pregnant, the Stravinskys spent the summer in La Baule in western France. In September, they moved to Clarens, Switzerland, where their second son, Soulima, was born.[31] The family would spend their summers in Russia and winters in Switzerland until 1914.[32] Diaghilev commissioned Stravinsky to score a second ballet for the 1911 Paris season. The result was Petrushka, based on the Russian folk tale featuring the titular character, a puppet, who falls in love with another, a ballerina.[33] Though it failed to capture the immediate reception that The Firebird had following its premiere at Théâtre du Châtelet in June 1911, the production continued Stravinsky's success.[34]

.jpg.webp)

It was Stravinsky's third ballet for Diaghilev, The Rite of Spring, that caused a sensation among critics, fellow composers, and concertgoers. Based on an idea thought up by Stravinsky while composing Firebird, the production features a series of primitive pagan rituals celebrating the advent of spring.[35] Stravinsky's score contained many novel features for its time, including experiments in tonality, metre, rhythm, stress and dissonance. The radical nature of the music and choreography caused a near-riot at its premiere at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on 29 May 1913.[36][37]

Shortly after the premiere, Stravinsky contracted typhoid from eating bad oysters and he was confined to a Paris nursing home. He left in July 1913 and returned to Ustilug.[38] For the rest of the summer he focused on his first opera, The Nightingale, based on a story by Hans Christian Andersen, which Stravinsky had started in 1908.[39] On 15 January 1914, Stravinsky and Nosenko had their fourth child, Marie Milène (or Maria Milena). After her delivery, Nosenko was discovered to have tuberculosis and was committed to a sanatorium in Leysin in the Alps. Stravinsky took up residence nearby, where he completed The Nightingale.[40][41] The work premiered in Paris in May 1914, after the Moscow Free Theatre had commissioned the piece for 10,000 roubles but soon became bankrupt. Diaghilev agreed that the Ballets Russes to stage it.[42][43] The opera had only lukewarm success with the public and the critics, apparently because its delicacy did not meet their expectations following the tumultuous Rite of Spring.[41] However, composers including Maurice Ravel, Béla Bartók, and Reynaldo Hahn found much to admire in the score's craftsmanship, even claiming to detect the influence of Arnold Schoenberg.[44]

In April 1914, Stravinsky and his family returned to Clarens.[45] Stravinsky was ineligible for military service in the World War due to his history of typhoid.[32] Stravinsky managed a short visit to Ustilug to retrieve personal items just before borders were closed.[46] In June 1915, he and his family moved from Clarens to Morges, a town six miles from Lausanne on the shore of Lake Geneva. The family lived there (at three different addresses), until 1920.[47] In December 1915, Stravinsky made his conducting debut at two concerts in aid of the Red Cross with The Firebird.[48] The war and subsequent Russian Revolution in 1917 made it impossible for Stravinsky to return to his homeland.[49]

Stravinsky began to struggle financially in the late 1910s. When Russia (and its successor, the USSR) did not adhere to the Berne Convention and the aftermath of World War I left countries in ruin, royalties for performances of Stravinsky's pieces stopped coming.[50][51] Stravinsky, seeking financial assistance, approached the Swiss philanthropist Werner Reinhart, who agreed to sponsor him and largely underwrite the first performance of L'Histoire du soldat in September 1918.[52] In gratitude, Stravinsky dedicated the work to Reinhart and gave him the original manuscript.[51] Reinhart supported Stravinsky further when he funded a series of concerts of his chamber music in 1919.[53][54] In gratitude to his benefactor, Stravinsky dedicated his Three Pieces for Solo Clarinet to Reinhart, who was an amateur clarinettist.[55] Stravinsky travelled to Paris to attend the premiere of Pulcinella by the Ballets Russes on 15 May 1920, returning to Switzerland afterwards.[56]

Life in France, 1920–1939

In June 1920, Stravinsky and his family left Switzerland for France, first settling in Carantec for the summer while they sought a permanent home in Paris.[57][58]

They soon heard from the couturière Coco Chanel, who invited the family to live in her Paris mansion until they had found their own residence. The Stravinskys accepted and arrived in September.[59] Stravinsky and Chanel quickly became lovers, but the affair was short and ended in May 1921.[60] She helped secure a guarantee for a revival production of The Rite of Spring by the Ballets Russes from December 1920 with an anonymous gift to Diaghilev that was claimed to be worth 300,000 francs.[61]

In 1920, Stravinsky signed a contract with the French piano manufacturing company Pleyel. As part of the deal, Stravinsky transcribed most of his compositions for their player piano, the Pleyela. The company helped collect Stravinsky's mechanical royalties for his works and provided him with a monthly income. In 1921, he was given studio space at their Paris headquarters where he worked and entertained friends and acquaintances.[62][63][64] The piano rolls were not recorded, but were instead marked up from a combination of manuscript fragments and handwritten notes by Jacques Larmanjat, musical director of Pleyel's roll department. During the 1920s, Stravinsky recorded Duo-Art piano rolls for the Aeolian Company in London and New York City.[65]

Stravinsky met Vera Sudeikin in Paris in February 1921,[66] while she was married to the painter and stage designer Serge Sudeikin, and they began an affair that led to Vera Sudeikin leaving her husband in the spring of 1922.[67]

In May 1921, Stravinsky and his family moved to Anglet, a town close to the Spanish border.[68] Their stay was short-lived as by autumn, they had settled to nearby Biarritz and Stravinsky completed his Trois mouvements de Petrouchka, a piano transcription of excerpts from Petrushka for Artur Rubinstein. Diaghilev then requested orchestrations for a revival production of Tchaikovsky's The Sleeping Beauty.[69] From then until his wife's death in 1939, Stravinsky led a double life, dividing his time between his family in Anglet, and Vera Sudeikin in Paris and on tour.[70] Nosenko reportedly bore her husband's situation "with a mixture of magnanimity, bitterness, and compassion".[71]

In June 1923, Stravinsky's ballet Les noces premiered in Paris and performed by the Ballets Russes.[72] In the following month, he started to receive money from an anonymous patron from the US who insisted on remaining anonymous and only identified themselves as "Madame". They promised to send him $6,000 in the course of three years, and sent Stravinsky an initial cheque for $1,000. Stravinsky's later student Robert Craft believed that the patron was the famed conductor Leopold Stokowski, whom Stravinsky had recently met, and theorised that the conductor wanted to win Stravinsky over to visit the US.[72][73]

In September 1924, Stravinsky bought a new home in Nice.[74] Here, the composer re-evaluated his religious beliefs and reconnected with his Christian faith with help from a Russian priest, Father Nicholas.[75] He also thought of his future, and used the experience of conducting the premiere of his Octet at one of Serge Koussevitzky's concerts the year before to build on his career as a conductor. Koussevitzky asked Stravinsky to compose a new piece for one of his upcoming concerts; Stravinsky agreed to a piano concerto. The Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments was first performed in May 1924 with Stravinsky as the soloist.[76] The piece was a success, and Stravinsky secured himself the exclusive rights to perform the work for the next five years.[77] Stravinsky visited Catalonia six times, and the first time, in 1924, after holding three concerts with the Pau Casals Orchestra at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, he said, "Barcelona will be unforgettable for me. What I liked most was the cathedral and the sardanas".[78] Following a European tour through the latter half of 1924, Stravinsky completed his first US tour in early 1925, which spanned two months.[79] It opened with Stravinsky conducting an all-Stravinsky programme at Carnegie Hall.[80]

In 1926, Stravinsky rejoined the Orthodox Church, having been moved by a ceremony at the Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua while on a spring concert tour.[81][82] In May 1927, Stravinsky's opera-oratorio Oedipus Rex premiered in Paris. The funding of its production was largely provided by Winnaretta Singer, Princesse Edmond de Polignac, who paid 12,000 francs for a private preview of the piece at her house. Stravinsky gave the money to Diaghilev to help finance the public performances. The premiere at the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt received a negative reaction, believed by the painter Boris Grigoriev to be due to its tameness compared to The Firebird, which irked Stravinsky, who had started to become annoyed at the public's fixation on his early ballets.[83] In the summer of 1927, Stravinsky received a commission from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, his first from the US. A wealthy patron of music, Coolidge requested a thirty-minute ballet score for a festival to be held at the Library of Congress, for a $1,000 fee.[84] Stravinsky accepted and wrote Apollo, which premiered in 1928.[85]

.jpg.webp)

After Diaghilev's death in 1929, Stravinsky continued touring across Europe, playing the premiere of his Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra at the Salle Pleyel on 6 December and performing it in many European towns afterwards.[86] Stravinsky toured for most of 1930 to 1933, also composing his Symphonies of Wind Instruments upon a commission from the Boston Symphony Orchestra and his Violin Concerto in D for Samuel Dushkin.[87] After touring the latter with Dushkin, Stravinsky was inspired to transcribe some of his works for violin and piano, later touring these transcriptions at "recitals" with Dushkin.[88] On 30 May 1934, the Stravinskys acquired French nationality by naturalization.[89] Later in that year, they moved to a house on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, where they stayed for five years.[86][90][91] The composer used his citizenship to publish his memoirs in French, entitled Chroniques de ma Vie in 1935. His only composition of that year was the Concerto for Two Solo Pianos, which was written for himself and his son Sviatoslav using a special double piano that Pleyel had built. The pair completed a tour of Europe and South America in 1936.[90] In April 1937, he directed his three-part ballet Jeu de cartes, a commission for Lincoln Kirstein's ballet company in New York City with choreography by George Balanchine.[92]

Upon his return to Europe, Stravinsky left Paris for Annemasse near the Swiss border to be near his family, after his wife and daughters Ludmila and Milena had contracted tuberculosis and were in a sanatorium.[93] Ludmila died in late 1938, followed by his wife of 33 years, in March 1939.[94] Stravinsky himself spent five months in hospital at Sancellemoz,[95] during which time his mother also died.[94] During his later years in Paris, Stravinsky had developed professional relationships with key people in the United States: he was already working on his Symphony in C for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and he had agreed to accept the Charles Eliot Norton Chair of Poetry of 1939–1940 at Harvard University and while there, deliver six lectures on music as part of the prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Lectures.[96][97][98]

Life in the United States, 1939–1971

Early US years, 1939–1945

Stravinsky arrived in New York City on 30 September 1939 and headed for Cambridge, Massachusetts, to fulfil his engagements at Harvard. During his first two months in the US, Stravinsky stayed at Gerry's Landing, the home of art historian Edward W. Forbes.[99] Vera Sudeikin arrived in January 1940 and the couple married on 9 March in Bedford, Massachusetts. After a period of travel, the two moved into a home in Beverly Hills, California, before they settled in Hollywood from 1941. Stravinsky felt the warmer Californian climate would benefit his health.[100] Stravinsky had adapted to life in France, but moving to America at the age of 58 was a very different prospect. For a while, he maintained a circle of contacts and émigré friends from Russia, but he eventually found that this did not sustain his intellectual and professional life. He was drawn to the growing cultural life of Los Angeles, especially during World War II, when writers, musicians, composers, and conductors settled in the area. The music critic Bernard Holland claimed Stravinsky was especially fond of British writers, who visited him in Beverly Hills, like W. H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, and later Dylan Thomas: "They shared the composer's taste for hard spirits – especially Aldous Huxley, with whom Stravinsky spoke in French."[101] Stravinsky and Huxley had a tradition of Saturday lunches for west coast avant-garde and luminaries.[102]

In 1940, Stravinsky completed his Symphony in C and conducted the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at its premiere later that year.[103] At this time, Stravinsky began to associate himself with film music; the first major film to use his music was Walt Disney's animated feature Fantasia (1940) which includes parts of The Rite of Spring rearranged by Leopold Stokowski to a segment depicting the history of Earth and the age of dinosaurs.[104] Orson Welles urged Stravinsky to write the score for Jane Eyre (1943), but negotiations broke down; a piece used in one of the film's hunting scenes was used in Stravinsky's orchestral work Ode (1943). An offer to score The Song of Bernadette (1943) also fell through; Stravinsky considered the terms were too much in the producer's favour. Music he had written for the film was later used in his Symphony in Three Movements.[104]

Stravinsky's unconventional dominant seventh chord in his arrangement of the "Star-Spangled Banner" led to an incident with the Boston police on 15 January 1944, and he was warned that the authorities could impose a $100 fine upon any "re-arrangement of the national anthem in whole or in part".[lower-alpha 3] The police, as it turned out, were wrong. The law in question forbade using the national anthem "as dance music, as an exit march, or as a part of a medley of any kind",[105] but the incident soon established itself as a myth, in which Stravinsky was supposedly arrested, held in custody for several nights, and photographed for police records.[106]

On 28 December 1945, the Stravinskys became naturalised US citizens.[107] Their sponsor and witness was the actor Edward G. Robinson.[108]

Last major works, 1945–1966

On the same day Stravinsky became an American citizen, he arranged for Boosey & Hawkes to publish rearrangements of several of his compositions and used his newly acquired American citizenship to secure a copyright on the material, thus allowing him to earn money from them.[109] The five-year contract was finalised and signed in January 1947 which included a guarantee of $10,000 per for the first two years, then $12,000 for the remaining three.[110]

In late 1945, Stravinsky received a commission from Europe, his first since Perséphone, in the form of a string piece for the 20th anniversary for Paul Sacher's Basle Chamber Orchestra. The Concerto in D premiered in 1947.[108][111] In January 1946, Stravinsky conducted the premiere of his Symphony in Three Movements at Carnegie Hall in New York City. It marked his first premiere in the US.[112] In 1947, Stravinsky was inspired to write his English-language opera The Rake's Progress by a visit to a Chicago exhibition of the same-titled series of paintings by the eighteenth-century British artist William Hogarth, which tells the story of a fashionable wastrel descending into ruin. W. H. Auden and writer Chester Kallman worked on the libretto. The opera premiered in 1951 and marks the final work of Stravinsky's neoclassical period.[113] While composing The Rake's Progress, Stravinsky met Robert Craft, whom Stravinsky invited to his home in Hollywood as a personal assistant.[114] Craft soon became Stravinsky's "closest friend, his confident, amanuensis, spokesman and fellow conductor," as Jay Harrison wrote in the New York Herald Tribune.[115] Craft encouraged the composer to explore serial music and the composers of the Second Viennese School, beginning Stravinsky's third and final distinct musical period, which lasted until his death.[116][117][118]

In 1953, Stravinsky agreed to compose a new opera with a libretto by Dylan Thomas, which detailed the recreation of the world after one man and one woman remained on Earth after a nuclear disaster. Development on the project came to a sudden end following Thomas's death in November of that year. Stravinsky completed In Memoriam Dylan Thomas, a piece for tenor, string quartet, and four trombones, in 1954.[119] Stravinsky composed his cantata Canticum Sacrum for the International Festival of Contemporary Music in Venice, to which he dedicated the work, and it premiered on 13 September 1956.[120] The work inspired the Norddeutscher Rundfunk to commission the musical setting Threni in 1957, which was premiered by their orchestra and chorus on 23 September 1958.[121][122] In 1959, Craft interviewed Stravinsky for an article titled Answers to 35 Questions, in which Stravinsky corrected a number of myths surrounding him and discussed his relationships with many of his collaborators. The article was later expanded into a book, and over the next four years, three more books of this fashion were published due to Craft's initiative.[123]

.tif.jpg.webp)

In 1961, the Stravinskys and Craft travelled to London, Zürich and Cairo on their way to Australia where Stravinsky and Craft conducted all-Stravinsky concerts in Sydney and Melbourne. They returned to California via New Zealand, Tahiti, and Mexico.[124][125] In January 1962, during his tour's stop in Washington, D.C., Stravinsky attended a dinner at the White House with President John F. Kennedy in honour of his 80th birthday, where he received a special medal for "the recognition his music has achieved throughout the world".[126][127] In September 1962, Stravinsky returned to Russia for the first time since 1914, accepting an invitation from the Union of Soviet Composers to conduct six performances in Moscow and Leningrad. During the three-week visit he met with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and several leading Soviet composers, including Dmitri Shostakovich and Aram Khachaturian.[128][129] Stravinsky did not return to his Hollywood home until December 1962 in what was almost eight months of continual travelling.[130] Following the assassination of Kennedy in 1963, Stravinsky completed his Elegy for J.F.K. in the following year. The two-minute work took the composer two days to write.[131]

By early 1964, the long periods of travel started to affect Stravinsky's health. His case of polycythemia worsened and his friends noticed that his movements and speech had slowed.[131] In 1965, Stravinsky agreed to have David Oppenheim produce a documentary film about himself for the CBS network. It involved a film crew following the composer at home and on tour that year, and he was paid $10,000 for the production.[132] The documentary includes Stravinsky's visit to Les Tilleuls, the house in Clarens where he wrote the majority of The Rite of Spring. The crew asked Soviet authorities for permission to film Stravinsky returning to his hometown of Ustilug, but the request was denied.[133] In 1966, Stravinsky completed his last major work, the Requiem Canticles.[134] His final attempt at composition, Two Sketches for a Sonata, existed in a manuscript of short piano fragments. The sketches were published by Boosey & Hawkes in 2021.[135]

Final years and death, 1967–1971

In March 1967, Stravinsky conducted L'Histoire du soldat with the Seattle Opera. By this time, Stravinsky's typical performance fee had grown to $10,000. However, after Stravinsky's conducting became "erratic" and "vague" as one reviewer described it, Craft cancelled all concerts that required Stravinsky to fly.[136] An exception to this was a concert at Massey Hall in Toronto in May 1967, where he conducted the relatively physically undemanding Pulcinella suite with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Unbeknownst to him, it was his final performance as conductor.[137][138] While backstage at the venue, Stravinsky informed Craft that he believed he had suffered a stroke.[136] In August 1967, Stravinsky was hospitalised in Hollywood for bleeding stomach ulcers and thrombosis which required a blood transfusion.[139]

By 1968, Stravinsky had recovered enough to resume touring across the US with him in the audience while Craft took to the conductor's post for the majority of the concerts. In May 1968, Stravinsky completed the piano arrangement of two songs by Hugo Wolf for a small orchestra.[140] In October, the Stravinskys and Craft travelled to Zürich to sort out business matters with Stravinsky's family.[141] The three considered relocating to Switzerland as they had become increasingly less fond of Hollywood, but they decided against it and returned to the US.[142]

In October 1969, after close to three decades in California and Stravinsky being denied to travel overseas by his doctors due to ill health, the Stravinskys secured a two-year lease for a luxury three bedroom apartment in Essex House in New York City. Craft moved in with them, effectively putting his career on hold to care for the ailing composer.[143] Among Stravinsky's final projects was orchestrating two preludes from Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier, but it was never completed.[144] In June 1970, he travelled to Évian-les-Bains by Lake Geneva where he reunited with his eldest son Fyodor and niece Xenia.[145]

On 18 March 1971, Stravinsky was taken to Lenox Hill Hospital with pulmonary edema where he stayed for ten days. On 29 March, he moved into a newly furnished apartment at 920 Fifth Avenue, his first city apartment since living in Paris in 1939. After a period of well-being, the edema returned on 4 April and Vera Stravinsky insisted that medical equipment should be installed in the apartment.[146] Stravinsky soon stopped eating and drinking and died at 5:20 a.m. on 6 April at the age of 88. The cause on his death certificate is heart failure. A funeral service was held three days later at Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel.[144] [147] In accordance with his wishes, he was buried in the Russian corner of the cemetery island of San Michele in Venice, several yards from the tomb of Sergei Diaghilev,[148][149] having been brought there by gondola after a service at Santi Giovanni e Paolo led by Cherubin Malissianos, Archimandrite of the Greek Orthodox Church.[148][150] During the service, his Requiem Canticles and organ music by Andrea Gabrieli were performed.[151]

Music

Most of Stravinsky's student works were composed for assignments from his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov, being mainly influenced by Rimsky-Korsakov and other Russian composers.[152] Stravinsky's first three ballets, The Firebird, Petrushka, and The Rite of Spring, were the beginning of his international fame and deviation from the conservative Saint Petersburg life.[152][153] Stravinsky's music is often divided into three periods of composition: his Russian period (1913–1920), where he was greatly influenced by Russian folklore and style;[154] his neoclassical period (1920–1951), where Stravinsky turned towards techniques and themes from the Classical period;[155][156] and his serial period (1954–1968), where Stravinsky used serial composition techniques pioneered by composers of the Second Viennese School.[157][118]

Student works, 1898–1907

Stravinsky's time before meeting Diaghilev was spent learning from Rimsky-Korsakov and his collaborators.[152] Only three works survive from before Stravinsky met Rimsky-Korsakov in August 1902: "Tarantella" (1898), Scherzo in G minor (1902), and The Storm Cloud, the first two being works for piano and the last for voice and piano.[158][159] Stravinsky's first assignment from Rimsky-Korsakov was the four-movement Piano Sonata in F♯ minor, which was also his first work to be performed in public.[160][161] Rimsky-Korsakov often gave Stravinsky the task of orchestrating various works to allow him to analyze the works' form and structure.[162] A number of Stravinsky's student compositions were performed at Rimsky-Korsakov's gatherings at his home; these include a set of bagatelles, a "chanson comique", and a cantata, showing the use of classical musical techniques that would later define Stravinsky's neoclassical period.[162] Stephen Walsh described this time in Stravinsky's musical career as "aesthetically cramped" due to the "cynical conservatism" of Rimsky-Korsakov and his music.[163] Rimsky-Korsakov thought the Symphony in E-flat (1907) was swayed too much by Glazunov's style, and disliked the modernist influence on Faun and Shepherdess (1907).[164]

First three ballets, 1910–1913

After the premiere of Scherzo fantastique and Feu d'artifice attracted the attention of Diaghilev, he commissioned Stravinsky to orchestrate Chopin's Nocturne in A-flat major and Grande valse brillante in E-flat major for the new ballet Les Sylphides, and commissioned Stravinsky's first ballet, The Firebird, a few months after.[165]

The Firebird used a harmonic structure that Stravinsky called "leit-harmony", a portmanteau of leitmotif and harmony used by Rimsky-Korsakov in his opera The Golden Cockerel.[166] The "leit-harmony" was used to juxtapose the protagonist, the Firebird, and the antagonist, Koschei the Deathless, the Firebird being associated with whole-tone phrases and Koschei being associated with octatonic music.[167] Stravinsky later wrote how he composed The Firebird in a state of "revolt against Rimsky", and that he "tried to surpass him with ponticello, col legno, flautando, glissando, and fluttertongue effects".[168]

Stravinsky's second ballet for the Ballets Russes, Petrushka, is where Stravinsky defined his musical character.[169] Originally meant to be a konzertstück for piano and orchestra, Diaghilev convinced Stravinsky that he should instead compose it as a ballet instead for the 1911 season.[33] The Russian influence can be seen in the use of a number of Russian folk tunes in addition to two waltzes by Viennese composer Joseph Lanner and a French music hall tune (La Jambe en bois or The Wooden Leg).[lower-alpha 4] Stravinsky also used a folk tune from Rimsky-Korsakov's opera The Snow Maiden, showing his continued influence on the music of Stravinsky.[170]

Stravinsky's third ballet, The Rite of Spring, caused a sensation at the premiere due to the avant-garde nature of the work.[35] Stravinsky had begun to experiment with polytonality in The Firebird and Petrushka, but for The Rite of Spring, he "pushed [it] to its logical conclusion," as Eric Walter White describes it.[171] In addition, the complex metre in the music consists of phrases combining conflicting time signatures and odd accents, such as the "jagged slashes" in the "Sacrificial Dance".[172][171] Both polytonality and unusual rhythms can be heard in the chords that open the second episode, "Augurs of Spring", consisting of an E♭ dominant 7 superimposed on an F♭ major triad written in an uneven rhythm, Stravinsky shifting the accents seemingly at random to create asymmetry.[173][174] The Rite of Spring is one of the most famous and influential works of the 20th century; the musicologist Donald Jay Grout described it as having "the effect of an explosion that so scattered the elements of musical language that they could never again be put together as before."[175]

Russian period, 1913–1920

The musicologist Jeremy Noble says that Stravinsky's "intensive researches into Russian folk material" took place during his time in Switzerland from 1914 to 1920.[154] The composer Béla Bartók considered Stravinsky's Russian period to have begun in 1913 with The Rite of Spring due to the works' use of Russian folk songs, themes, and techniques.[176] The use of duple or triple metres was especially prevalent in Stravinsky's Russian period music; while the pulse may have remained constant, the time signature would often change to constantly shift the accents.[177]

Stravinsky did not use as many folk melodies as he had in his first three ballets, but his works were with Russian style.[178] Stravinsky used folk poetry often; his next opera, Les noces, was based on texts from a collection of Russian folk poetry by Pyotr Kireevsky,[32][179] and his opera-ballet Renard was based on a folktale collected by Alexander Afanasyev.[180][181] Many of Stravinsky's Russian period works featured animal characters and themes, likely due to exposure to nursery rhymes he read with his four children.[182] Stravinsky also used unique theatrical styles. Les noces blended the ballet and cantata, a unique production described on the score as "Russian Choreographic Scenes".[183] In Renard, the voices were placed in the orchestra, as they were meant to accompany the action on stage.[182] L'Histoire du soldat was composed in 1918 with the Swiss novelist Charles F. Ramuz as a "quirky musical-theatre work" for dancers, a narrator, and a septet.[51] The work mixed the Russian folktales in the narrative with common musical structures of the time, like the tango, waltz, rag, and chorale.[184] According to Walsh, Stravinsky's music was always influenced by his Russian roots, and despite their decreased use in his later output, he maintained continuous musical innovation.[185]

Neoclassical period, 1920–1951

In Naples, Italy, Stravinsky saw a commedia dell'arte featuring the "great drunken lout" of a character Pulcinella, who would later become the subject of his ballet Pulcinella.[186] Officially begun in 1919,[187] Pulcinella was commissioned by Diaghilev after he proposed the idea of a ballet based on music by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Domenico Gallo, and others whose music was published under Pergolesi's name.[188][189] Composing a work based on harmonic and rhythmic systems by a late-Baroque era composer was the beginning of Stravinsky's turn towards 18th-century music that would "serve him for some 30 productive years."[188]

Although White and Jeremy Noble consider Stravinsky's neoclassical period to have begun in 1920 with his Symphonies for Wind Instruments,[152][155] Bartók argues that the period "really starts with his Octet for Wind Instruments, followed by his Concerto for Piano ..."[190] During this period, Stravinsky used techniques and themes from the Classical period of music.[190]

Greek mythology was a common theme in Stravinsky's neoclassical works. His first Greek mythology-based work was the ballet Apollon musagète (1927), choosing the leader of the Muses and god of art Apollo as the subject.[85] Stravinsky would use themes from Greek mythology in future works like Oedipus rex (1927), Persephone (1935), and Orpheus (1947).[191] Taruskin writes that Oedipus rex was "the product of Stravinsky's neo-classical manner at its most extreme," and that musical techniques "thought outdated" were juxtaposed against "a deliberately offputting hauteur."[192] In addition, Stravinsky turned towards older musical structures and techniques during this period and modernised them.[193][194] His Octet (1923) uses the sonata form, modernising it by disregarding the standard ordering of themes and traditional tonal relationships for different sections.[193] The idea of musical counterpoint, commonly used in the Baroque era, was used throughout the choral Symphony of Psalms.[195]

Stravinsky's neoclassical period ended in 1951 with the opera The Rake's Progress.[196][197] Taruskin described the opera as "the hub and essence of 'neo-classicism'." He points out how the opera contains numerous references to Greek mythology and other operas like Don Giovanni and Carmen, but still "embody[s] the distinctive structure of a fairy tale." Stravinsky was inspired by the operas of Mozart in composing the music, but other scholars also point out influence from Handel, Gluck, Beethoven, Schubert, Weber, Rossini, Donizetti, and Verdi.[198][199] The Rake's Progress has become an important work in opera repertoire, being "[more performed] than any other opera written after the death of Puccini."[200]

Serial period, 1954–1968

In the 1950s, Stravinsky began using serial compositional techniques such as the twelve-tone technique originally devised by Arnold Schoenberg.[201] Noble writes that this time was "the most profound change in Stravinsky's musical vocabulary," partly due to Stravinsky's newfound interest in the music of the Second Viennese School after meeting Robert Craft.[157]

Stravinsky first experimented with non-twelve-tone serial techniques in vocal and chamber works such as the Cantata (1952), the Septet (1953) and Three Songs from Shakespeare (1953). The first of his compositions fully based on such techniques was In Memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954). Agon (1954–57) was the first of his works to include a twelve-tone series and the second movement from Canticum Sacrum (1956) was the first piece to contain a movement entirely based on a tone row.[118] Agon's unique tonal structure was significant to Stravinsky's serial music; the work begins diatonic, moves towards full 12-tone serialism in the middle, and returns to diatonicism in the end.[202] Stravinsky returned to sacred themes in works such as Canticum Sacrum, Threni (1958), A Sermon, a Narrative and a Prayer (1961), and The Flood (1962). Stravinsky used a number of concepts from earlier works in his serial pieces; for example, the voice of God being two bass voices in homophony seen in The Flood was previously used in Les noces.[202] Stravinsky's final work, the Requiem Canticles (1966), made use of a complex four-part array of tone rows throughout, showing the evolution of Stravinsky's serialist music.[203][202] Noble describes the Requiem Canticles as "a distillation both of the liturgical text and of his own musical means of setting it, evolved and refined through a career of more than 60 years."[204]

Influence from other composers can be seen throughout this period. Stravinsky was heavily influenced by Schoenberg, not only in his use of the twelve-tone technique, but also in the distinctly "Schoenbergian" instrumentation of the Septet and the "Stravinskian interpretation of Schoenberg's Klangfarbenmelodie" found in Stravinsky's Variations.[157][202] Stravinsky also used a number of themes found in works by Benjamin Britten,[202] commenting in Themes and Conclusions about the "many titles and subjects [I have shared] with Mr. Britten already."[205] In addition, Stravinsky was very familiar with the works of Anton Webern, being one of the figures who inspired Stravinsky to consider serialism a possible form of composition.[206]

Influences

Literary

.jpg.webp)

Stravinsky displayed a taste in literature that was wide and reflected his constant desire for new discoveries.[207] The texts and literary sources for his work began with interest in Russian folklore.[208][154] After moving to Switzerland in 1914, Stravinsky began gathering folk stories from numerous collections, which were later used in works like Les noces, Renard, Pribaoutki, and various songs.[32] Many of Stravinsky's works, including The Firebird, Renard, and L'Histoire du soldat were inspired by Alexander Afanasyev's famous collection Russian Folk Tales.[209][180][210] Collections of folk music influenced Stravinsky's music; numerous melodies from The Rite of Spring were found in an anthology of Lithuanian folk songs.[211]

An interest in the Latin liturgy began shortly after Stravinsky rejoined the church in 1926, beginning with the composition of his first religious work in 1926 Pater Noster, written in Old Church Slavonic.[81][82] He later used three psalms from the Latin Vulgate in his Symphony of Psalms for orchestra and mixed choir.[212][213] Many works in the composer's neoclassical and serial periods used (or were based on) liturgical texts.[82][214]

Stravinsky worked with many authors throughout his career. He first worked with the Swiss novelist Charles F. Ramuz on L'Histoire du soldat in 1918, who wrote the text and helped form the idea.[51] In 1933, Ida Rubinstein commissioned Stravinsky to set music to a poem by André Gide, later becoming the melodrama Persephone.[215] The two collaborated well at first, but disagreements over the text caused Gide to leave the project.[216] The story of The Rake's Progress was first conceived by Stravinsky and W. H. Auden, the latter of whom wrote the libretto with Chester Kallman.[217][218] Stravinsky befriended many other authors as well, including T.S. Eliot,[207] Aldous Huxley, Christopher Isherwood, and Dylan Thomas,[101] the last of whom Stravinsky began working with on an opera in 1953 but stopped due to Thomas's death.[119]

Artistic

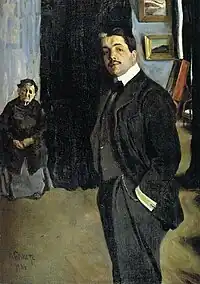

Stravinsky worked with some of the most famous artists of his time, many of whom he met after the premiere of The Firebird.[153][219] Diaghilev was one of the composer's most prominent artistic influences, having introduced him to composing for the stage and bringing him international fame with his first three ballets.[219][220] Through the Ballets Russes and Diaghilev, Stravinsky worked with figures like Vaslav Nijinsky, Léonide Massine,[153] Alexandre Benois,[153] Michel Fokine, and Léon Bakst.[221] The composer's interest in art propelled him to develop a strong relationship with Picasso, whom he met in 1917.[222] From 1917 to 1920, the two engaged in an artistic dialogue in which they exchanged small-scale works of art to each other as a sign of intimacy, which included the famous portrait of Stravinsky by Picasso,[223] and a short sketch of clarinet music by Stravinsky.[224] This exchange was essential to establish how the artists would approach their collaborative space in Ragtime and Pulcinella.[225][226]

Legacy

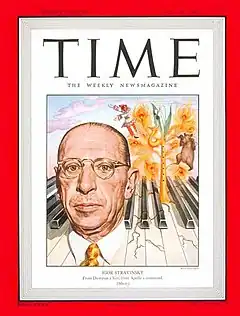

Stravinsky is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the 20th century.[156][219][227][228][229] In 1998, Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people of the century.[230] Stravinsky was not only recognised for his composing; he also achieved fame as a pianist and as a conductor; Philip Glass wrote in 1998, "He conducted with an energy and vividness that completely conveyed his every musical intention. Here was Stravinsky, a musical revolutionary whose own evolution never stopped. There is not a composer who lived during his time or is alive today who was not touched, and sometimes transformed, by his work."[227][230]

Stravinsky had a number of dissenters throughout his career, particularly regarding his later works.[231][232] In 1935, the American composer Marc Blitzstein compared Stravinsky to Jacopo Peri and C. P. E. Bach, conceding that, "There is no denying the greatness of Stravinsky. It is just that he is not great enough."[233] In 1934, the composer Constant Lambert described pieces such as L'Histoire du soldat as containing "essentially cold-blooded abstraction ... melodic fragments in Histoire du Soldat are completely meaningless themselves. They are merely successions of notes that can conveniently be divided into groups of three, five, and seven and set against other mathematical groups."[234][235] On the contrary, Erik Satie argued that measuring the "greatness" of an artist by comparing him to other artists is illusory, and that every piece of music should be judged on its own merits and not by comparing it to the standards of other composers.[236]

Stravinsky's reputation in Russia and the USSR varied. Performances of his music were banned from around 1933 until 1962, the year Khrushchev invited him to the USSR for an official visit. In 1972, an official proclamation by the Soviet Minister of Culture, Yekaterina Furtseva, ordered Soviet musicians to "study and admire" Stravinsky's music, and she made hostility toward it a potential offence.[237][238]

White writes that the attention given to the composer's first three ballets undermined the importance of his later works, and that works like Les noces, the Symphony of Psalms, and Persephone "represent the high-water mark of his invention and form one of the most precious contributions to the musical treasury of the twentieth century."[239] The conductor Michael Tilson Thomas said in a 2013 interview for NPR, "[Stravinsky] had insatiable curiosity about words, about geography, about just things that he encountered in his day-to-day life ... he was never going to stay still, he was always going to move forward."[240] Georg Predota's profile of Stravinsky for Interlude says regarding Stravinsky's vast styles, "he might well have represented the face of an entire century as his works touch almost every important trend and tendency the century had on offer."[228]

.jpg.webp)

Stravinsky was noted for his distinctive use of rhythm, especially in The Rite of Spring.[241] According to Glass, "the idea of pushing the rhythms across the bar lines ... led the way ... [for] the rhythmic structure of music [to become] much more fluid and in a certain way spontaneous."[242] Glass also noted Stravinsky's "primitive, offbeat rhythmic drive".[227] Andrew J. Browne wrote, "Stravinsky is perhaps the only composer who has raised rhythm in itself to the dignity of art."[243] Over the course of his career, Stravinsky called for a wide variety of orchestral, instrumental, and vocal forces, ranging from single instruments in such works as Three Pieces for Solo Clarinet (1918) or Elegy for Solo Viola (1944) to the enormous orchestra of The Rite of Spring (1913), which Copland characterised as "the foremost orchestral achievement of the 20th century".[244]

Stravinsky influenced many composers and musicians.[245] George Benjamin wrote in The Guardian that, "Since 1913 generation after generation of composers – from Varèse to Boulez, Bartók to Ligeti — has felt impelled to face the challenges set by [The Rite of Spring],"[1] while Walsh wrote, "For younger composers of almost every persuasion, his work has continued to offer inspiration and a source of method."[246] Stravinsky's rhythm and vitality greatly influenced Aaron Copland and Pierre Boulez, the latter who Stravinsky had worked with on Threni.[247][248][245] Stravinsky's combination of folklore and modernism influenced the works and style of Béla Bartók as well.[249] Stravinsky also influenced composers like Elliott Carter, Harrison Birtwistle, and John Tavener.[245] Included among his students are Robert Craft, Robert Strassburg, and Warren Zevon.[250][251]

Honours

Stravinsky received the Royal Philharmonic Society's gold medal in 1954,[252] the Léonie Sonning Music Prize in 1959,[253] and the Wihuri Sibelius Prize in 1963.[254] On 25 July 1966, he was awarded the Portuguese Military Order of Saint James of the Sword.[255] In 1977, the "Sacrificial Dance" from The Rite of Spring was included among many tracks around the world on the Voyager Golden Record.[256] In 1982, the composer was featured on a 2¢ postage stamp by the United States Postal Service as part of its Great Americans stamp series.[257] He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960[258] and was posthumously inducted into the National Museum of Dance and Hall of Fame in 2004.[259]

A number of major works were dedicated to Stravinsky, including En blanc et noir by Claude Debussy, Trois poèmes de Mallarmé by Maurice Ravel,[260] and the revised version of La tragédie de Salomé by Florent Schmitt.[261] The composer received five Grammy Awards and eleven total nominations.[262] Three records of his works were inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1993, 1999, and 2000, and he was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987.[263][264][265]

Recordings

Stravinsky found recordings a practical and useful tool in preserving his thoughts on the interpretation of his music. As a conductor of his own music, he recorded primarily for Columbia Records, beginning in 1928 with a performance of the original suite from The Firebird and concluding in 1967 with the 1945 suite from the same ballet.[265] In the late 1940s he made several recordings for RCA Victor at the Republic Studios in Los Angeles.[266] Although most of his recordings were made with studio musicians, he also worked with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra, the CBC Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.[266]

During his lifetime, Stravinsky appeared on several telecasts, including the 1962 world premiere of The Flood on CBS Television. Although he made an appearance, the actual performance was conducted by Craft.[267] Numerous films and videos of the composer have been preserved, including the 1966 award-winning National Film Board of Canada documentary Stravinsky, directed by Roman Kroitor and Wolf Koenig, in which he conducts the CBC Symphony Orchestra in a recording of the Symphony of Psalms.[268]

Writings

Stravinsky published a number of books throughout his career, almost always with the aid of a (sometimes uncredited) collaborator. In his 1936 autobiography, Chronicle of My Life, which was written with the help of Walter Nouvel, Stravinsky included his well-known statement that "music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all".[269] With Alexis Roland-Manuel and Pierre Souvtchinsky, he wrote his 1939–40 Harvard University Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, which were delivered in French and first collected under the title Poétique musicale in 1942 and then translated in 1947 as Poetics of Music.[lower-alpha 5] In 1959, several interviews between the composer and Craft were published as Conversations with Igor Stravinsky,[270] which was followed by a further five volumes over the following decade. A collection of Stravinsky's writings and interviews appears under the title Confidences sur la musique.[271]

Books and articles are selected from Appendix E of Eric Walter White's Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works and Stephen Walsh's profile of Stravinsky on Oxford Music Online.[272][273]

Books

- Stravinsky, Igor (1936). Chronicle of My Life. London: Gollancz. OCLC 1354065. Originally published in French as Chroniques de ma vie, 2 vols. (Paris: Denoël et Steele, 1935), subsequently translated (anonymously) as Chronicle of My Life. This edition reprinted as Igor Stravinsky – An Autobiography, with a preface by Eric Walter White (London: Calder and Boyars, 1975) ISBN 978-0-7145-1063-7, 0-7145-1082-3. Reprinted again as An Autobiography (1903–1934) (London: Boyars, 1990) ISBN 978-0-7145-1063-7, 0-7145-1082-3. Also published as Igor Stravinsky – An Autobiography (New York: M. & J. Steuer, 1958), and An Autobiography. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1962). ISBN 978-0-393-00161-7. OCLC 311867794.

- — (1947). Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons: The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures for 1939–1940. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674678569. OCLC 155726113.

- —; Craft, Robert (1959). Conversations with Igor Stravinsky. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. OCLC 896750. Reprinted Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0-520-04040-3.

- —; — (1960). Memories and Commentaries. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780520044029. Reprinted 1981, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04402-9 The 2002 reprinted "One-Volume Edition" varies from the 1960 original, London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-21242-2.

- —; — (1962). Expositions and Developments. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780520044036. Reprinted, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981.

- —; — (1963). Dialogues and a Diary. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. OCLC 896750. The 1968 reprinted Dialogues varies from the 1963 original, London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-10043-0.

- —; — (1966). Themes and Episodes. New York: A. A. Knopf.

- —; — (1969). Retrospectives and Conclusions. New York: A. A. Knopf.

- —; — (1972). Themes and Conclusions. London: Faber and Faber. A one-volume edition of Themes and Episodes (1966) and Retrospectives and Conclusions (1969) as revised by Igor Stravinsky in 1971. ISBN 978-0-571-08308-4.

Articles

- Stravinsky, Igor (29 May 1913). Canudo, Ricciotto (ed.). "Ce que j'ai voulu exprimer dans "Le sacre du printemps"" [What I Wanted to Express in The Rite of Spring]. Montjoie! (in French). No. 2. At DICTECO

- —— (15 May 1921). "Les Espagnols aux Ballets Russes" [The Spaniards at the Ballets Russes]. Comœdia (in French). At DICTECO

- —— (18 October 1921). "The Genius of Tchaikovsky". The Times (Open Letter to Letter to Diaghilev). London.

- —— (18 May 1922). "Une lettre de Stravinsky sur Tchaikovsky" [A Letter from Stravinsky on Tchaikovsky]. Le Figaro (in French). At DICTECO

- —— (1924). "Some Ideas about my Octuor". The Arts. Brooklyn. At SCRIBD.

- —— (1927). "Avertissement... a Warning". The Dominant. London.

- —— (29 April 1934). "Igor Strawinsky nous parle de 'Perséphone'" [Igor Stravinsky tells us about Persephone]. Excelsior (in French). At DICTECO

- —— (15 December 1935). "Quelques confidences sur la musique" [Some secrets about music]. Conferencia (in French). Paris. At DICTECO

- ——; Nouvel, Walter (1935–1936). Chroniques de ma vie (in French). Paris: Denoël & Steele. OCLC 250259515. Translated in English, 1936, as An Autobiography.

- —— (28 January 1936). "Ma candidature à l'Institut" [My application to the Institute]. Jour (in French). Paris.

- —— (1940). Pushkin: Poetry and Music. New York. OCLC 1175989080.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ——; Nouvel, Walter (1953). "The Diaghilev I Knew". The Atlantic Monthly. pp. 33–36.

References

Notes

- ↑ Pronunciation: /strəˈvɪnski/; Russian: Игорь Фёдорович Стравинский, IPA: [ˈiɡərʲ ˈfʲɵdərəvʲɪtɕ strɐˈvʲinskʲɪj] ⓘ

- ↑ See "Sacrificial Dance" from The Rite of Spring (audio, animated score) on YouTube, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas conducting (1972)

- ↑ According to Michael Steinberg's liner notes to Stravinsky in America, RCA 09026-68865-2, p. 7, the police "removed the parts from Symphony Hall", quoted in Thom 2007, p. 50.

- ↑ See: "Table I: Folk and Popular Tunes in Petrushka" Taruskin (1996, pp. I: 696–697).

- ↑ The names of uncredited collaborators are given in Walsh 2001.

Citations

- 1 2 Benjamin 2013.

- ↑ Greene 1985, p. 1101.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 19–21.

- 1 2 Walsh 2002.

- ↑ Vlad 1967, p. 3.

- ↑ Walsh 2001, 1. Background and early years, 1882–1905.

- ↑ Pisalnik 2012.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, pp. 6, 17.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 21.

- ↑ Stravinsky 1962, p. 8.

- 1 2 Dubal 2003, p. 564.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 23–24.

- 1 2 3 Dubal 2003, p. 565.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 25.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 83.

- ↑ Walsh 2001, 2. Towards The Firebird, 1902–09.

- ↑ Stravinsky 1962, p. 24.

- ↑ Walsh 2015.

- 1 2 White 1979, p. 22.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 28.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.c.

- 1 2 White 1979, p. 29.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.d.

- ↑ Sadie & Sadie 2005, p. 359.

- ↑ Sadie & Sadie 2005, p. 360.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.e.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, pp. 140–143.

- ↑ Whiting 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 4 White 1979, p. 51.

- 1 2 White 1979, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 37.

- 1 2 Stravinsky 1962, p. 31.

- ↑ Service 2013.

- ↑ Hewett 2013.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, pp. 100, 102.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, pp. 111–114.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 224.

- 1 2 V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 119.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 221.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 113.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 120.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 233.

- ↑ Oliver 1995, p. 74.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 56.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 469.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 65.

- 1 2 3 4 Keller 2011, p. 456.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Stravinsky 1962, p. 83.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 70.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.a.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 313.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 315.

- ↑ Stravinsky 1962, pp. 84–86.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 318.

- ↑ Taruskin 1996, Vol. 1, p. 1516; Simon 2011, p. 38.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 319 and fn 21.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 78.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 619.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.f.

- ↑ Lawson 1986, pp. 297–301.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 336.

- ↑ Kay n.d.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 329.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 77.

- ↑ Cooper 2000, p. 306.

- ↑ Joseph 2001, p. 73.

- 1 2 Traut 2016, p. 8.

- ↑ Craft 1992, pp. 73–81.

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 193.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 51.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 87.

- ↑ Fontelles-Ramonet 2021.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.g.

- 1 2 White 1979, pp. 89, 90.

- 1 2 3 Steinberg 2005, p. 270.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 91.

- 1 2 White 1979, p. 92.

- 1 2 White 1979, p. 98.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 98–100.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ "Journal officiel de la République française. Lois et décrets". Gallica. 10 June 1934. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- 1 2 Routh 1975, p. 41.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 105.

- ↑ Routh 1975, p. 43.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 29.

- 1 2 Whiting 2005, p. 38.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 18.

- ↑ Joseph 2001, p. 279.

- ↑ Routh 1975, p. 44.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 595.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 115.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 116.

- 1 2 Holland 2001.

- ↑ Braubach 2009.

- ↑ Routh 1975, p. 46.

- 1 2 Routh 1975, p. 47.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.i.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 152.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 429.

- 1 2 Walsh 2006, p. 185.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 124.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 201.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 190.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Whiting 2005, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 131.

- ↑ Quoted in Walsh (2006, pp. 419).

- ↑ White 1979, p. 133.

- ↑ Whiting 2005, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Straus 2001, p. 4.

- 1 2 Routh 1975, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 136.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 137.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 504.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Cunningham 2012.

- ↑ Anonymous 2022.

- ↑ Anonymous 1962a.

- ↑ Anonymous 1962b.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 146–148.

- ↑ Anonymous 1962c.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 476.

- 1 2 Walsh 2006, p. 488.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 501.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, pp. 503–504.

- ↑ Whiting 2005, p. 41.

- ↑ Anonymous 2021.

- 1 2 Walsh 2006, p. 528.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 528, 529.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 154.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 532.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 155.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, pp. 542–543.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 544.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 550.

- 1 2 Henahan 1971.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 158.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 560.

- ↑ Walsh 2006, p. 561.

- 1 2 Anonymous 1971.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 159.

- ↑ Rolls Press & Popperfoto 1971.

- ↑ Collarile 2021, p. 104.

- 1 2 3 4 White & Noble 1980, p. 240.

- 1 2 3 4 Walsh 2003, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 White & Noble 1980, p. 248.

- 1 2 White & Noble 1980, p. 253.

- 1 2 Walsh 2003, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 White & Noble 1980, p. 259.

- ↑ Walsh 2003, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Taruskin 1996, p. I: 100.

- ↑ Walsh 2003, p. 4.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 9.

- 1 2 White 1979, p. 10.

- ↑ Walsh 2003, p. 5.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 12.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ McFarland 1994, pp. 205, 219.

- ↑ McFarland 1994, p. 209.

- ↑ McFarland 1994, p. 219 quoting Stravinsky & Craft 1962, p. 128.

- ↑ Taruskin 1996, p. I: 662.

- ↑ Taruskin 1996, p. I: 698.

- 1 2 White 1957, p. 61.

- ↑ Hill 2000, p. 86.

- ↑ Hill 2000, p. 63.

- ↑ Ross 2008, p. 75.

- ↑ Grout & Palisca 1981, p. 713.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 149.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 563.

- ↑ White & Noble 1980, p. 249.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 145.

- 1 2 White 1979, p. 240.

- ↑ Walsh 2003, p. 16.

- 1 2 White & Noble 1980, p. 250.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 144.

- ↑ Zak 1985, p. 105.

- ↑ Walsh 2001, 4. Exile in Switzerland, 1914–20.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 62.

- ↑ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 183.

- 1 2 White & Noble 1980, p. 251.

- ↑ Freed 1981.

- 1 2 V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 218.

- ↑ Lowe 2016.

- ↑ Taruskin 1992a, pp. 651–652.

- 1 2 Szabo 2011, pp. 19–22.

- ↑ Szabo 2011, p. 39.

- ↑ Szabo 2011, p. 23.

- ↑ Szabo 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ White & Noble 1980, p. 256.

- ↑ Taruskin 1992b, pp. 1222–1223.

- ↑ White & Noble 1980, p. 257.

- ↑ Taruskin 1992b, p. 1220.

- ↑ Craft 1982.

- 1 2 3 4 5 White & Noble 1980, p. 261.

- ↑ Straus 1999, p. 67.

- ↑ White & Noble 1980, pp. 261–262.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 539.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 134.

- 1 2 Predota 2021b.

- ↑ Taruskin 1980, pp. 501.

- ↑ Taruskin 1996, p. 558, 559.

- ↑ Zak 1985, p. 103.

- ↑ Taruskin 1980, pp. 502.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 359, 360.

- ↑ Steinberg 2005, p. 268.

- ↑ Zinar 1978, pp. 177.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 375.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 376, 377.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 451, 452.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 146.

- 1 2 3 Anonymous n.d.y.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 560, 561.

- ↑ White 1979, p. 32.

- ↑ Nandlal 2017, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1959, p. 117.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.j.

- ↑ Nandlal 2017, pp. 81.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1959, pp. 116–117.

- 1 2 3 Glass 1998.

- 1 2 Predota 2021a.

- ↑ Lamb 2019.

- 1 2 Anonymous 1999.

- ↑ White 1997, p. 7.

- ↑ Walsh 2003, p. 49.

- ↑ Blitzstein 1935, p. 330.

- ↑ Lambert 1934, p. 94.

- ↑ Lambert 1934, pp. 101–105.

- ↑ Satie 1923.

- ↑ Karlinsky 1985, p. 282.

- ↑ Norris 1976, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ White 1997, p. 171.

- ↑ Siegel & Tilson Thomas 2013.

- ↑ Simon & Alsop 2007.

- ↑ Simeone, Craft & Glass 1999.

- ↑ Browne 1930, p. 360.

- ↑ Copland 1952, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 Cross 1998, p. 6.

- ↑ Walsh 2003, p. 50.

- ↑ Matthews 1970–1971, p. 11.

- ↑ Schiff 1995.

- ↑ Taruskin 1998.

- ↑ Pfitzinger 2017, p. 17.

- ↑ Plasketes 2016, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.k.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.l.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.m.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.n.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.o.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.p.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.q.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.r.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.s.

- ↑ Pasler 2001, p. 543.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.t.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.u.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.v.

- 1 2 Anonymous n.d.w.

- 1 2 Boretz & Cone 1968, pp. 268–288.

- ↑ Cross n.d.

- ↑ Anonymous n.d.x.

- ↑ Stravinsky 1936, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1959.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Dufour 2013.

- ↑ White 1979, pp. 621–624.

- ↑ Walsh 2001, "Writings".

Sources

- Anonymous (19 January 1962a). "Kennedy Entertains Igor Stravinsky at Dinner". The New York Times. p. 6. Retrieved 22 March 2023. Facsimile. Shortened at "Stravinsky to Be Kennedy Guest at White House". Herald & Review. Decatur, Illinois. 10 January 1962. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020.

- Anonymous (16 January 1962b). "Stravinsky to Get Medal at Dinner". The Terre Haute Star. Washington. p. 1. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (21 September 1962c). "Stravinsky in Russia after 52 years away". The Evening Sun. Baltimore. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (16 April 1971). "Stravinsky Is Interred in Venice Near Grave of Friend Diaghilev". The New York Times. p. 40. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (14 June 1999). "TIME 100 Persons Of The Century". Time. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- Anonymous (March 2021). "Stravinsky Anniversary: Two Sketches for a Sonata published". Boosey & Hawkes. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- Anonymous (9 May 2022). "Stravinsky conducts Stravinsky in Australia in 1961". ABC Classic. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.a). "Stravinsky: Histoire du Soldat Suite". NAXOS Direct. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014.

- Anonymous (n.d.c). "Устилузький народний музей Ігоря Стравінського" [Ustilug Folk Museum of Igor Stravinsky]. Museums of the Volyn (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 11 October 2016.

- Anonymous (n.d.d). "A virtual tour of the house-museum of Igor Stravinsky in Ustilug". House-Museum of Igor Stravinsky in Ustilug (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 8 August 2020.

- Anonymous (n.d.e). "International Music Festival "Stravinsky and Ukraine"". Lutsk. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018.

- Anonymous (n.d.f). "Composers and the Pianola – Igor Stravinsky". The Pianola Institute. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.g). "Concert details: RL Copied Thursday, January 8, 1925 at 8:30 PM". Carnegie Hall. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.i). "Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 249 § 9". Archived from the original on 20 November 2011.

- Anonymous (n.d.j). "Stravinsky and Picasso: how two cultural giants became collaborators". Classic FM. The Sunday Times. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.k). "RPS Gold Medal". Royal Philharmonic Society. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.l). "The Léonie Sonning Music Prize 2022". Royal Danish Theatre. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.m). "Wihuri Sibelius Price". Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.n). "Cidadãos Estrangeiros Agraciados com Ordens Portuguesas". Página Oficial das Ordens Honoríficas Portuguesas (in Portuguese). Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.o). "Music from Earth". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.p). "2c Igor Stravinsky Single". National Postal Museum. Smithsonian. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.q). "Igor Stravinsky". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.r). "Hall of Fame". National Museum of Dance and Hall of Fame. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.s). "As dedicatee: Igor Stravinsky". IMSLP. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.t). "Igor Stravinsky". Grammy Awards. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.u). "Lifetime Achievement Award". Grammy Awards. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.v). "Grammy Hall of Fame Award". Grammy Awards. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.w). "Miniature masterpieces". Fondation Igor Stravinsky. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- Anonymous (n.d.x). "Stravinsky". National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Anonymous (n.d.y). "Igor Stravinsky". British Library. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- Benjamin, George (29 May 2013). "How Stravinsky's Rite of Spring has shaped 100 years of music". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- Blitzstein, Marc (July 1935). "The Phenomenon of Stravinsky". The Musical Quarterly. 75 (4): 51–69. doi:10.1093/mq/75.4.51. ISSN 0027-4631. JSTOR 741833.

- Boretz, Benjamin; Cone, Edward T. (1968). "Igor Stravinsky: A Discography of the Composer's Performances". Perspectives on Schoenberg and Stravinsky. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7843-7.

- Braubach, Mary Ann (2009). Huxley on Huxley (documentary).

- Browne, Andrew J. (October 1930). "Aspects of Stravinsky's Work". Music & Letters. Oxford University Press. 11 (4): 360–366. doi:10.1093/ml/XI.4.360. ISSN 0027-4224. JSTOR 726868.

- Cooper, John Xiros (2000). T.S. Eliot's Orchestra: Critical Essays on Poetry and Music. New York: Garland. ISBN 978-0-8153-2577-2.

- Copland, Aaron (1952). Music and Imagination. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-58915-5.

- Craft, Robert (December 1982). "Assisting Stravinsky – On a misunderstood collaboration". The Atlantic. pp. 64–74. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Craft, Robert (1992). Stravinsky: Glimpses of a Life. London: Lime Tree. ISBN 978-0-413-45461-4.

- Cross, Jonathan (n.d.). "Stravinsky, Igor: The Flood – Work details and repertoire note". Boosey & Hawkes. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Cross, Jonathan (1998). The Stravinsky Legacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56365-9.

- Collarile, Luigi (2021). "Andrea Gabrieli for Igor Stravinsky (Venice, 15 April 1971): The Choice of Sandro Dalla Libera". Archival Notes (6): 101–110. ISSN 2499-832X. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Cunningham, Harriet (25 February 2012). "Echoes of greatness". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Dubal, David (24 October 2003). The Essential Canon of Classical Music. New York: North Point Press. ISBN 978-0-86547-664-6.

- Freed, Richard (26 July 1981). "The Pergolesi Puzzle". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- Fontelles-Ramonet, Albert (2021). "Igor Stravinsky a Barcelona: escàndols i triomfs entre concerts i lleure" [Igor Stravinsky in Barcelona: scandals and triumphs between concerts and leisure]. Revista Musical Catalana (in Catalan) (373): 30–34. ISSN 1887-2980.

- Glass, Philip (8 June 1998). "The Classical Musician Igor Stravinsky". Time. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Greene, David Mason (1985). Petrak, Albert M. (ed.). Greene's Biographical Encyclopedia of Composers. Reproducing Piano Roll Fnd. ISBN 978-0-385-14278-6.

- Grout, Donald Jay; Palisca, Claude V. (1981). A History of Western Music (3rd ed.). London and Melbourne: J. M. Dent & Sons. ISBN 978-0-460-04546-9.

- Henahan, Donal (7 April 1971). "Igor Stravinsky, the Composer, Dead at 88". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Hewett, Ivan (29 May 2013). "Did The Rite of Spring really spark a riot?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020.

- Hill, Peter (2000). Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62714-6.

- Holland, Bernard (11 March 2001). "Stravinsky, a Rare Bird Amid the Palms; A Composer in California, At Ease if Not at Home". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Joseph, Charles M. (2001). Stravinsky Inside Out. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12936-6.

- Karlinsky, Simon (July 1985). "Searching for Stravinskii's Essence". The Russian Review. 44 (3): 281–287. doi:10.2307/129304. JSTOR 129304.

- Kay, Graeme (n.d.). "Vera de Bosset Sudeikina (Vera Stravinsky) (1888-1982)". BBC Radio 3. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Keller, James M. (2011). Chamber Music: A Listener's Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-020639-0.

- Lamb, Bill (11 March 2019). "Biography of Igor Stravinsky, Revolutionary Russian Composer". liveaboutdotcom. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Lambert, Constant (1934). Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Lawson, Rex (1986). "Stravinsky and the Pianola". In Pasler, Jan (ed.). Confronting Stravinsky: Man, Musician, and Modernist. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05403-5.

- Lowe, Dominic (27 September 2016). ""Sing O Muse": Salonen explores Stravinsky inspired by Greek myth". Bachtrack. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Matthews, David (Winter 1970–1971). "Copland and Stravinsky". Tempo (95): 10–14. doi:10.1017/S0040298200026577. ISSN 0040-2982. JSTOR 944065. S2CID 145054429.

- McFarland, Mark (1994). ""Leit-harmony", or Stravinsky's Musical Characterization in "The Firebird"". International Journal of Musicology. Peter Lang. 3: 203–233. ISSN 0941-9535. JSTOR 24618812.

- Nandlal, Carina (22 May 2017). "Picasso and Stravinsky: Notes on the Road from Friendship to Collaboration". Colloquy. Monash University (22): 81–88. doi:10.4225/03/5922784a722cd.

- Norris, Geoffrey (September 1976). "Review of I. F. Stravinsky: Stat'i i Materialy". Tempo. Cambridge University Press (118): 39–40. ISSN 0040-2982. JSTOR 944233.

- Oliver, Michael (1995). Igor Stravinsky. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3158-9.

- Pasler, Jann (2001). "Schmitt, Florent". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- Pfitzinger, Scott (2017). Composer Genealogies: A Compendium of Composers, Their Teachers, and Their Students. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-7225-5.