Gujarat | |

|---|---|

From top and L-R: Sabarmati Ashram, Gujarati attire, Somnath Temple, Rann of Kutch, Dwarkadhish Temple, Statue of Unity, Laxmi Vilas Palace at Vadodara | |

| Etymology: Land of Gurjars | |

| Nickname: "Jewel of Western India" | |

| Motto: Satyameva Jayate (Truth alone triumphs) | |

| Anthem: Jai Jai Garavi Gujarat ("Victory to Proud Gujarat")[1] | |

Location of Gujarat in India | |

| Coordinates: 23°13′12″N 72°39′18″E / 23.220°N 72.655°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | West India |

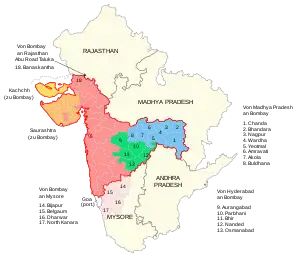

| Before was | Bombay State |

| Formation (by bifurcation) | 1 May 1960 |

| Capital | Gandhinagar |

| Largest city | Ahmedabad |

| Largest metro | Ahmedabad |

| Districts | 33 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Government of Gujarat |

| • Governor | Acharya Devvrat |

| • Chief minister | Bhupendrabhai Patel (BJP) |

| State Legislature | Unicameral |

| • Assembly | Gujarat Legislative Assembly (182 seats) |

| National Parliament | Parliament of India |

| • Rajya Sabha | 11 seats |

| • Lok Sabha | 26 seats |

| High Court | Gujarat High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 196,024 km2 (75,685 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 5th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 590 km (370 mi) |

| • Width | 500 km (300 mi) |

| Elevation | 137 m (449 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 1,145 m (3,757 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −1 m (−3 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | |

| • Rank | 9th |

| • Density | 308/km2 (800/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 42.6% |

| • Rural | 57.4% |

| Demonym | Gujarati[3] • [4][5] |

| Language | |

| • Official | Gujarati, Hindi |

| • Official script | Gujarati script, Devanagari script |

| GDP | |

| • Total (2020-2021) | |

| • Rank | 4th |

| • Per capita | |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-GJ |

| Vehicle registration | GJ |

| HDI (2019) | |

| Literacy (2011) | |

| Sex ratio (2011) | 919♀/1000 ♂[9] (16th) |

| Website | gujaratindia |

| Symbols of Gujarat | |

| |

| Song | Jai Jai Garavi Gujarat ("Victory to Proud Gujarat")[1] |

| Foundation day | Gujarat Day |

| Bird | Greater flamingo |

| Fish | Blackspotted croaker[10] |

| Flower | Marigold[11] |

| Fruit | Mango[12] |

| Mammal | Asiatic lion[11] |

| Tree | Banyan[11] |

| State highway mark | |

| |

| State highway of Gujarat GJ SH1 - GJ SH173 | |

| List of Indian state symbols | |

| ^† The state of Bombay was divided into two states i.e. Maharashtra and Gujarat by the Bombay (Reorganisation) Act 1960. | |

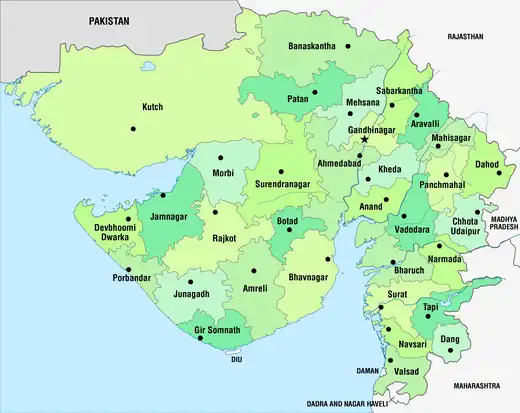

Gujarat (/ˌɡʊdʒəˈrɑːt/ GUUJ-ə-RAHT, Gujarati: [ˈɡudʒəɾat̪] ⓘ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about 1,600 km (990 mi) is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some 196,024 km2 (75,685 sq mi); and the ninth-most populous state, with a population of 60.4 million. It is bordered by Rajasthan to the northeast, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu to the south, Maharashtra to the southeast, Madhya Pradesh to the east, and the Arabian Sea and the Pakistani province of Sindh to the west. Gujarat's capital city is Gandhinagar, while its largest city is Ahmedabad.[13] The Gujaratis are indigenous to the state and their language, Gujarati, is the state's official language.

The state encompasses 23 sites of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation (more than any other state). The most important sites are Lothal (the world's first dry dock), Dholavira (the fifth largest site), and Gola Dhoro (where 5 uncommon seals were found). Lothal is believed to have been one of the world's first seaports.[14] Gujarat's coastal cities, chiefly Bharuch and Khambhat,[15] served as ports and trading centres in the Maurya and Gupta empires and during the succession of royal Saka dynasties in the Western Satraps era.[16][17] Along with Bihar, Mizoram and Nagaland, Gujarat is one of four Indian states to prohibit the sale of alcohol.[18] The Gir Forest National Park in Gujarat is home to the only wild population of the Asiatic lion in the world.[19]

The economy of Gujarat is the fourth-largest in India, with a gross state domestic product (GSDP) of ₹16.55 trillion (equivalent to ₹19 trillion or US$230 billion in 2023) and has the country's 10th-highest GSDP per capita of ₹215,000 (US$2,700).[6] Gujarat ranks 21st among Indian states and union territories in human development index.[20] Gujarat is regarded as one of the most industrialised states and has a low unemployment rate,[21] but the state ranks poorly on some social indicators and is at times affected by religious violence.[22]

Etymology

Gujarat is derived from the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty, who ruled Gujarat in the 8th and 9th centuries CE.[23][24][25][26] Parts of modern Rajasthan and Gujarat have been known as Gurjarat or Gurjarabhumi for centuries before the Mughal period.[27]

History

Ancient history

Gujarat was one of the main central areas of the Indus Valley civilisation, which is centred primarily in modern Pakistan.[28] It contains ancient metropolitan cities from the Indus Valley such as Lothal, Dholavira and Gola Dhoro.[29] The ancient city of Lothal was where India's first port was established.[14] The ancient city of Dholavira is one of the largest and most prominent archaeological sites in India, belonging to the Indus Valley civilisation. The most recent discovery was Gola Dhoro. Altogether, about fifty Indus Valley settlement ruins have been discovered in Gujarat.[30]

The ancient history of Gujarat was enriched by the commercial activities of its inhabitants. There is clear historical evidence of trade and commerce ties with Egypt, Bahrain and Sumer in the Persian Gulf during the time period of 1000 to 750 BCE.[30][32] There was a succession of various Indian empires such as the Mauryan dynasty, Western Satraps, Satavahana dynasty, Gupta Empire, Chalukya dynasty, Rashtrakuta Empire, Pala Empire and Gurjara-Pratihara Empire, as well as the Maitrakas and then the Chaulukyas.

The early history of Gujarat includes the imperial grandeur of Chandragupta Maurya who conquered a number of earlier states in what is now Gujarat. Pushyagupta, a Vaishya, was appointed the governor of Saurashtra by the Mauryan regime. He ruled Girinagar (modern-day Junagadh) (322 BCE to 294 BCE) and built a dam on the Sudarshan lake. Emperor Ashoka the Great, the grandson of Chandragupta Maurya, not only ordered his edicts engraved in the rock at Junagadh, but also asked Governor Tusherpha to cut canals from the lake where an earlier Indian governor had built a dam. Between the decline of Mauryan power and Saurashtra coming under the sway of the Samprati Mauryas of Ujjain, there was an Indo-Greek defeat in Gujarat of Demetrius. In 16th century manuscripts, there is an apocryphal story of a merchant of King Gondophares landing in Gujarat with Apostle Thomas. The incident of the cup-bearer torn apart by a lion might indicate that the port city described is in Gujarat.[33][34]

For nearly 300 years from the start of the 1st century CE, Saka rulers played a prominent part in Gujarat's history. The weather-beaten rock at Junagadh gives a glimpse of the ruler Rudradaman I (100 CE) of the Saka satraps known as Western Satraps, or Kshatraps. Mahakshatrap Rudradaman I founded the Kardamaka dynasty which ruled from Anupa on the banks of the Narmada up to the Aparanta region bordering Punjab. In Gujarat, several battles were fought between the Indian dynasties such as the Satavahana dynasty and the Western Satraps. The greatest and the mightiest ruler of the Satavahana dynasty was Gautamiputra Satakarni who defeated the Western Satraps and conquered some parts of Gujarat in the 2nd century CE.[35]

The Kshatrapa dynasty was replaced by the Gupta Empire with the conquest of Gujarat by Chandragupta Vikramaditya. Vikramaditya's successor Skandagupta left an inscription (450 CE) on a rock at Junagadh which gives details of the governor's repairs to the embankment surrounding Sudarshan lake after it was damaged by floods. The Anarta and Saurashtra regions were both parts of the Gupta empire. Towards the middle of the 5th century, the Gupta empire went into decline. Senapati Bhatarka, the general of the Guptas, took advantage of the situation and in 470 set up what came to be known as the Maitraka state. He shifted his capital from Giringer to Valabhi, near Bhavnagar, on Saurashtra's east coast. The Maitrakas of Vallabhi became very powerful with their rule prevailing over large parts of Gujarat and adjoining Malwa. A university was set up by the Maitrakas, which came to be known far and wide for its scholastic pursuits and was compared with the noted Nalanda University. It was during the rule of Dhruvasena Maitrak that Chinese philosopher-traveler Xuanzang/ I Tsing visited in 640 along the Silk Road.[37]

Gujarat was known to the ancient Greeks and was familiar with other Western centers of civilisation through the end of the European Middle Ages. The oldest written record of Gujarat's 2,000-year maritime history is documented in a Greek book titled The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century.[38][39]

Medieval history

In the early 8th century, the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate established an empire in the name of the rising religion of Islam, which stretched from Spain in the west to Afghanistan and modern-day Pakistan in the east. Al-Junaid, the successor of Qasim, finally subdued the Hindu resistance within Sindh and established a secure base. The Arab rulers tried to expand their empire southeast, which culminated in the Caliphate campaigns in India fought in 730; they were defeated and expelled west of the Indus river, probably by a coalition of the Indian rulers Nagabhata I of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty, Vikramaditya II of the Chalukya dynasty and Bappa Rawal of the Guhila dynasty. After this victory, the Arab invaders were driven out of Gujarat. General Pulakeshin, a Chalukya prince of Lata, received the title Avanijanashraya (refuge of the people of the earth) and honorific of "Repeller of the unrepellable" by the Chalukya emperor Vikramaditya II for his victory at the battle at Navsari, where the Arab troops suffered a crushing defeat.[40]

In the late 8th century, the Kannauj Triangle period started. The three major Indian dynasties – the northwestern Indian Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty, the southern Indian Rashtrakuta dynasty and the eastern Indian Pala Empire – dominated India from the 8th to 10th centuries. During this period the northern part of Gujarat was ruled by the northern Indian Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty and the southern part of Gujarat was ruled by the southern Indian Rashtrakuta dynasty.[41] However, the earliest epigraphical records of the Gurjars of Broach attest that the royal bloodline of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty of Dadda I, II and III (650–750) ruled south Gujarat.[42] Southern Gujarat was ruled by the Indian Rashtrakuta dynasty until it was captured by the Indian ruler Tailapa II of the Western Chalukya Empire.[43]

Zoroastrians from Greater Iran migrated to the western borders of India (Gujarat and Sindh) during the 8th or 10th century,[44] to avoid persecution by Muslim invaders who were in the process of conquering Iran. The descendants of those Zoroastrian refugees came to be known as the Parsi.[45][46][47][48]

Subsequently, Lāṭa in southern Gujarat was ruled by the Rashtrakuta dynasty until it was captured by the Western Chalukya ruler Tailapa II.[43][49]

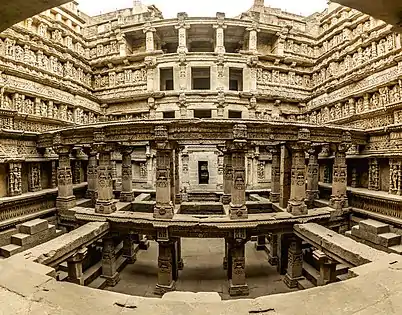

The Chaulukya dynasty[50] ruled Gujarat from c. 960 to 1243. Gujarat was a major center of Indian Ocean trade, and their capital at Anhilwara (Patan) was one of the largest cities in India, with a population estimated at 100,000 in the year 1000. After 1243, the Solankis lost control of Gujarat to their feudatories, of whom the Vaghela chiefs of Dholka came to dominate Gujarat. In 1292 the Vaghelas became tributaries of the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri in the Deccan. Karandev of the Vaghela dynasty was the last Hindu ruler of Gujarat. He was defeated and overthrown by the superior forces of Alauddin Khalji from Delhi in 1297. With his defeat, Gujarat became part of the Delhi Sultanate, and the Rajput hold over Gujarat would never be restored.

Fragments of printed cotton from Gujarat have been discovered in Egypt, providing evidence for medieval trade in the western Indian Ocean.[51] These fragments represent the Indian cotton traded in Egypt during the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods, from the tenth to sixteenth centuries. Similar cotton was also traded as far east as Indonesia.[51]

Muslim rule

Islamic conquests, 1197–1614

After the Ghoris had assumed a position of Muslim supremacy over North India, Qutbuddin Aibak attempted to conquer Gujarat and annex it to his empire in 1197, but failed in his ambitions.[52] An independent Muslim community continued to flourish in Gujarat for the next hundred years, championed by Arab merchants settling along the western coast. From 1297 to 1300, Alauddin Khalji, the Turko-Afghan Sultan of Delhi, destroyed the Hindu metropolis of Anhilwara and incorporated Gujarat into the Delhi Sultanate. After Timur sacked Delhi at the end of the 14th century, weakening the Sultanate, Gujarat's Muslim Khatri governor Zafar Khan Muzaffar (Muzaffar Shah I) asserted his independence, and his son, Sultan Ahmed Shah (ruled 1411–1442), established Ahmedabad as the capital. Khambhat eclipsed Bharuch as Gujarat's most important trade port. Gujarat's relations with Egypt, which was then the premier Arab power in the Middle East, remained friendly over the next century and the Egyptian scholar, Badruddin-ad-Damamimi, spent several years in Gujarat in the shade of the Sultan before proceeding to the Bahmani Sultanate on the Deccan Plateau.[53][54]

Shah e Alam, a famous Sufi saint of the Chishti order who was the descendant of Makhdoom Jahaniyan Jahangasht from Bukhara, soon arrived in a group that included Arab theologian Ibn Suwaid, several Sayyid Sufi members of the Aydarus family of Tarim in Yemen,[55] Iberian court interpreter Ali al-Andalusi from Granada,[56] and the Arab jurist Bahraq from Hadramaut who was appointed a tutor of the prince.[57] Among the illustrious names who arrived during the reign of Mahmud Begada was the philosopher Haibatullah Shah Mir from Shiraz, and the scholar intellectual Abu Fazl Ghazaruni from Persia[58][59] who tutored and adopted Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, author of the Akbarnama.[60] Later, a close alliance between the Ottoman Turks and Gujarati sultans to effectively safeguard Jeddah and the Red Sea trade from Portuguese imperialism, encouraged the existence of powerful Rumi elites within the kingdom who took the post of viziers in Gujarat keen to maintain ties with the Ottoman state.[61][62][63][64][65]

Humayun also briefly occupied the province in 1536, but fled due to the threat Bahadur Shah, the Gujarat king, imposed.[66] The Sultanate of Gujarat remained independent until 1572, when the Mughal emperor Akbar conquered it and annexed it to the Mughal Empire.[67]

The Surat port (the only Indian port facing west) then became the principal port of India during Mughal rule, gaining widespread international repute. The city of Surat, famous for its exports of silk and diamonds, had reached a par with contemporary Venice and Beijing, great mercantile cities of Europe and Asia,[68] and earned the distinguished title, Bab al-Makkah (Gate of Mecca).[16][17]

Drawn by the religious renaissance taking place under Akbar, Mohammed Ghaus moved to Gujarat and established spiritual centers for the Shattari Sufi order from Iran, founding the Ek Toda Mosque and producing such devotees as Wajihuddin Alvi of Ahmedabad whose many successors moved to Bijapur during the height of the Adil Shahi dynasty.[69] At the same time, Zoroastrian high priest Azar Kayvan who was a native of Fars, immigrated to Gujarat founding the Zoroastrian school of illuminationists which attracted key Shi'ite Muslim admirers of the Safavid philosophical revival from Isfahan.

Early 14th-century Maghrebi adventurer, Ibn Batuta, who famously visited India with his entourage, recalls in his memoirs about Cambay, one of the great emporia of the Indian Ocean that indeed:

Cambay is one of the most beautiful cities as regards the artistic architecture of its houses and the construction of its mosques. The reason is that the majority of its inhabitants are foreign merchants, who continually build their beautiful houses and wonderful mosques – an achievement in which they endeavor to surpass each other.

Many of these "foreign merchants" were transient visitors, men of South Arabian and Persian Gulf ports, who migrated in and out of Cambay with the rhythm of the monsoons. But others were men with Arab or Persian patronyms whose families had settled in the town generations, even centuries earlier, intermarrying with Gujarati women, and assimilating everyday customs of the Hindu hinterland.[70]

The Age of Discovery heralded the dawn of pioneer Portuguese and Spanish long-distance travel in search of alternative trade routes to "the East Indies", moved by the trade of gold, silver and spices. In 1497, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama is said to have discovered the Europe-to-India sea route which changed the course of history, thanks to Kutchi sailor Kanji Malam, who showed him the route from the East African coasts of Mozambique sailing onwards to Calicut off the Malabar coast in India.[71][72][73] Later, the Gujarat Sultanate allied with the Ottomans and Egyptian Mamluks naval fleets led by governor-generals Malik Ayyaz and Amir Husain Al-Kurdi, vanquished the Portuguese in the 1508 Battle of Chaul resulting in the first Portuguese defeat at sea in the Indian Ocean.[74]

To 16th-century European observers, Gujarat was a fabulously wealthy country. The customs revenue of Gujarat alone in the early 1570s was nearly three times the total revenue of the whole Portuguese empire in Asia in 1586–87, when it was at its height.[75] Indeed, when the British arrived on the coast of Gujarat, houses in Surat already had windows of Venetian glass imported from Constantinople through the Ottoman empire.[76] In 1514, the Portuguese explorer Duarte Barbosa described the cosmopolitan atmosphere of Rander known otherwise as City of Mosques in Surat province, which gained the fame and reputation of illustrious Islamic scholars, Sufi-saints, merchants and intellectuals from all over the world:[77]

Ranel (Rander) is a good town of the Moors, built of very pretty houses and squares. It is a rich and agreeable place ... the Moors of the town trade with Malacca, Bengal, Tawasery (Tannasserim), Pegu, Martaban, and Sumatra in all sort of spices, drugs, silks, musk, benzoin and porcelain. They possess very large and fine ships and those who wish Chinese articles will find them there very completely. The Moors of this place are white and well dressed and very rich they have pretty wives, and in the furniture of these houses have china vases of many kinds, kept in glass cupboards well arranged. Their women are not secluded like other Moors, but go about the city in the day time, attending to their business with their faces uncovered as in other parts.

The conquest of the Kingdom of Gujarat marked a significant event of Akbar's reign. Being the major trade gateway and departure harbour of pilgrim ships to Mecca, it gave the Mughal Empire free access to the Arabian sea and control over the rich commerce that passed through its ports. The territory and income of the empire were vastly increased.[78]

The Sultanate of Gujarat and the merchants

For the best part of two centuries, the independent Khatri Sultanate of Gujarat was the cynosure of its neighbours on account of its wealth and prosperity, which had long made the Gujarati merchant a familiar figure in the ports of the Indian Ocean.[53][79] Gujaratis, including Hindus and Muslims as well as the enterprising Parsi class of Zoroastrians, had been specialising in the organisation of overseas trade for many centuries, and had moved into various branches of commerce such as commodity trade, brokerage, money-changing, money-lending and banking.[80]

By the 17th century, Chavuse and Baghdadi Jews had assimilated into the social world of the Surat province, later on their descendants would give rise to the Sassoons of Bombay and the Ezras of Calcutta, and other influential Indian-Jewish figures who went on to play a philanthropical role in the commercial development of 19th-century British Crown Colony of Shanghai.[81] Spearheaded by Khoja, Bohra, Bhatiya shahbandars and Moorish nakhudas who dominated sea navigation and shipping, Gujarat's transactions with the outside world had created the legacy of an international transoceanic empire which had a vast commercial network of permanent agents stationed at all the great port cities across the Indian Ocean. These networks extended to the Philippines in the east, East Africa in the west, and via maritime and the inland caravan route to Russia in the north.[82]

Tomé Pires, a Portuguese official at Malacca, wrote of conditions during the reigns of Mahmud I and Mozaffar II:

"Cambay stretches out two arms; with her right arm she reaches toward Aden and with the other towards Malacca"[83]

He also described Gujarat's active trade with Goa, the Deccan Plateau and the Malabar. His contemporary, Duarte Barbosa, describing Gujarat's maritime trade, recorded the import of horses from the Middle East and elephants from Malabar, and lists exports which included muslins, chintzes and silks, carnelian, ginger and other spices, aromatics, opium, indigo and other substances for dyeing, cereals and legumes.[84] Persia was the destination for many of these commodities, and they were partly paid for in horses and pearls taken from Hormuz.[85] The latter item, in particular, led Sultan Sikandar Lodi of Delhi, according to Ali-Muhammad Khan, author of the Mirat-i-Ahmadi, to complain that the

support of the throne of Delhi is wheat and barley but the foundation of the realm of Gujarat is coral and pearls[86]

Hence, the sultans of Gujarat possessed ample means to sustain lavish patronage of religion and the arts, to build madrasas and ḵānaqāhs, and to provide douceurs for the literati, mainly poets and historians, whose presence and praise enhanced the fame of the dynasty.[87]

Even at the time of Tomé Pires' travel to the East Indies in the early 16th century, Gujarati merchants had earned an international reputation for their commercial acumen and this encouraged the visit of merchants from Cairo, Armenia, Abyssinia, Khorasan, Shiraz, Turkestan and Guilans from Aden and Hormuz.[88] Pires noted in his Suma Orientale:[89]

These [people] are [like] Italians in their knowledge of and dealings in merchandise ... they are men who understand merchandise; they are so properly steeped in the sound and harmony of it, that the Gujaratees say that any offence connected with merchandise is pardonable. There are Gujaratees settled everywhere. They work some for some and others for others. They are diligent, quick men in trade. They do their accounts with fingers like ours and with our very writings.

Gujarat in the Mughal Empire

Gujarat was one of the twelve original subahs (imperial top-level provinces) established by Mughal Emperor (Badshah) Akbar, with seat at Ahmedabad, bordering on Thatta (Sindh), Ajmer, Malwa and later Ahmadnagar subahs.

Aurangzeb, who was better known by his imperial title Alamgir ("Conqueror of the World"), was born at Dahod, Gujarat, and was the sixth Mughal Emperor ruling with an iron fist over most of the Indian subcontinent. He was the third son and sixth child of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal. At the time of his birth, his father, Shah Jahan, was then the Subahdar (governor) of Gujarat, and his grandfather, Jehangir, was the Mughal Emperor. Before he became emperor, Aurangzeb was made Subahdar of Gujarat subah as part of his training and was stationed at Ahmedabad. Aurangzeb was a notable expansionist and was among the wealthiest of the Mughal rulers, with an annual yearly tribute of £38,624,680 (in 1690). During his lifetime, victories in the south expanded the Mughal Empire to more than 3.2 million square kilometres and he ruled over a population estimated as being in the range of 100–150 million subjects.

Aurangzeb had great love for his place of birth. In 1704, he wrote a letter to his eldest son, Muhammad Azam Shah, asking him to be kind and considerate to the people of Dahod as it was his birthplace. Muhammad Azam was then the Subedar (governor) of Gujarat.

In his letter, Aurangzeb wrote:[90]

My son of exalted rank, the town of Dahod, one of the dependencies of Gujarat, is the birthplace of this sinner. Please consider a regard for the inhabitants of that town as incumbent on you.

Maratha Empire

When the cracks had started to develop in the edifice of the Mughal Empire in the mid-17th century, the Marathas were consolidating their power in the west, Chatrapati Shivaji, the great Maratha ruler, attacked Surat in southern Gujarat twice first in 1664 and again in 1672.[91] These attacks marked the entry of the Marathas into Gujarat. However, before the Maratha had made inroads into Gujarat, the Europeans had made their presence felt, led by the Portuguese, and followed by the Dutch and the English.

The Peshwas had established sovereignty over parts of Gujarat and collected taxes and tributes through their representatives. Damaji Rao Gaekwad and Kadam Bande divided the Peshwa territory between them,[92] with Damaji establishing the sway of Gaekwad over Gujarat and making Baroda (present day Vadodara in southern Gujarat) his capital. The ensuing internecine war among the Marathas was fully exploited by the British, who interfered in the affairs of both Gaekwads and the Peshwas.

In Saurashtra, as elsewhere, the Marathas were met with resistance.[93] The decline of the Mughal Empire helped form larger peripheral states in Saurashtra, including Junagadh, Jamnagar, Bhavnagar and a few others, which largely resisted the Maratha incursions.[93]

European colonialism, 1614–1947

In the 1600s, the Dutch, French, English and Portuguese all established bases along the western coast of the region. Portugal was the first European power to arrive in Gujarat, and after the Battle of Diu, acquired several enclaves along the Gujarati coast, including Daman and Diu as well as Dadra and Nagar Haveli. These enclaves were administered by Portuguese India under a single union territory for over 450 years, only to be later incorporated into the Republic of India on 19 December 1961 by military conquest.

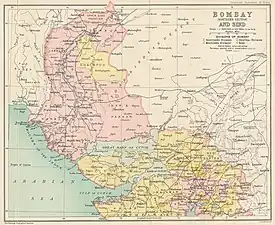

The British East India Company established a factory in Surat in 1614 following the commercial treaty made with Mughal Emperor Nuruddin Salim Jahangir, which formed their first base in India, but it was eclipsed by Bombay after the English received it from Portugal in 1668 as part of the marriage treaty of Charles II of England and Catherine of Braganza, daughter of King John IV of Portugal. The state was an early point of contact with the west, and the first British commercial outpost in India was in Gujarat.[94]

17th-century French explorer François Pyrard de Laval, who is remembered for his 10-year sojourn in South Asia, bears witness in his account that the Gujaratis were always prepared to learn workmanship from the Portuguese, and in turn imparted skills to the Portuguese:[95]

I have never seen men of wit so fine and polished as are these Indians: they have nothing barbarous or savage about them, as we are apt to suppose. They are unwilling indeed to adopt the manners and customs of the Portuguese; yet do they regularly learn their manufactures and workmanship, being all very curious and desirous of learning. In fact, the Portuguese take and learn more from them than they from the Portuguese.

Later in the 17th century, Gujarat came under control of the Hindu Maratha Empire that arose, defeating the Muslim Mughals who had dominated the politics of India. Most notably, from 1705 to 1716, Senapati Khanderao Dabhade led the Maratha Empire forces in Baroda. Pilaji Gaekwad, first ruler of Gaekwad dynasty, established the control over Baroda and other parts of Gujarat.

The British East India Company wrested control of much of Gujarat from the Marathas during the Second Anglo-Maratha War in 1802–1803. Many local rulers, notably the Maratha Gaekwad Maharajas of Baroda (Vadodara), made a separate peace with the British and acknowledged British sovereignty in return for retaining local self-rule.

An epidemic outbreak in 1812 killed half the population of Gujarat.[96]

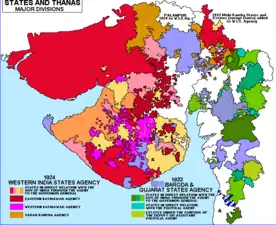

Gujarat was placed under the political authority of the Bombay Presidency, with the exception of Baroda State, which had a direct relationship with the Governor-General of India. From 1818 to 1947, most of present-day Gujarat, including Kathiawar, Kutch and northern and eastern Gujarat were divided into hundreds of princely states, but several districts in central and southern Gujarat, namely Ahmedabad, Broach (Bharuch), Kaira (Kheda), Panchmahal and Surat, were governed directly by British officials. In 1819, Sahajanand Swami established the World's First Swaminarayan Mandir in Kalupur, Ahmedabad.

Princely states of Gujarat in 1924

Princely states of Gujarat in 1924 Bombay Presidency in 1909, northern portion

Bombay Presidency in 1909, northern portion Mahatma Gandhi picking salt at Dandi beach, South Gujarat, ending the Salt satyagraha on 5 April 1930

Mahatma Gandhi picking salt at Dandi beach, South Gujarat, ending the Salt satyagraha on 5 April 1930 Foundational Swaminarayan Mandir, est. 1819

Foundational Swaminarayan Mandir, est. 1819

Post-independence

Initially there was confusion over whether Junagadh would join India or Pakistan. This was resolved in 1947 with a plebiscite for full union with India following the next year.[97]

After Indian independence and the partition of India in 1947, the new Indian government grouped the former princely states of Gujarat into three larger units; Saurashtra, which included the former princely states on the Kathiawad peninsula, Kutch, and Bombay state, which included the former British districts of Bombay Presidency together with most of Baroda State and the other former princely states of eastern Gujarat. Bombay state was enlarged to include Kutch, Saurashtra (Kathiawar) and parts of Hyderabad state and Madhya Pradesh in central India. The new state had a mostly Gujarati-speaking north and a Marathi-speaking south. Agitation by Gujarati nationalists, the Mahagujarat Movement, and Marathi nationalists, the Samyukta Maharashtra, for their own states led to the split of Bombay state on linguistic lines; on 1 May 1960, it became the new states of Gujarat and Maharashtra. In 1969 riots, at least 660 died and properties worth millions were destroyed.[98][99]

The first capital of Gujarat was Ahmedabad. The capital of Gujarat was moved to Gandhinagar in 1970. Nav Nirman Andolan was a socio-political movement of 1974. It was a students' and middle class people's movement against economic crisis and corruption in public life. This was the first and last successful agitation after the Independence of India that ousted an elected government.[100][101][102]

Gujarat has emerged as an important industrial hub in India. In Western India Surat was among the strongest industrial clusters in the 1970s. Between 1971 and 1981 diamond cutting was established as industry in Surat. At the same time the production of artificial silk and a substantial petrochemical industry became a fixture in Surat.[103]

The Morvi dam failure, in 1979, resulted in the death of thousands of people and large economic loss.[104] In the 1980s, a reservation policy was introduced in the country, which led to anti-reservation protests in 1981 and 1985. The protests witnessed violent clashes between people belonging to various castes.[105]

The 2001 Gujarat earthquake was located about 9 km south-southwest of the village of Chobari in the Bhachau taluka of Kutch District. This magnitude 7.7 shock killed around 20,000 people (including at least 18 in South-eastern Pakistan), injured another 167,000 and destroyed nearly 400,000 homes.[106]

In February 2002, the Godhra train burning led to statewide riots, resulting in the deaths of 1044 people – 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus, and hundreds missing still unaccounted for.[107] Akshardham Temple was attacked by two terrorists in September 2002, killing 32 people and injuring more than 80 others. National Security Guards intervened to end the siege killing both terrorists.[108] On 26 July 2008 a series of seventeen bomb blasts rocked Ahmedabad, killing and injuring several people.[109]

Geography

Gujarat borders the Tharparkar, Badin and Thatta districts of Pakistan's Sindh province to the northwest, is bounded by the Arabian Sea to the southwest, the state of Rajasthan to the northeast, Madhya Pradesh to the east, and by Maharashtra, the Union Territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu to the south. Historically, the north was known as Anarta, the Kathiawar peninsula, "Saurastra", and the south as "Lata".[110] Gujarat was also known as Pratichya and Varuna.[111] The Arabian Sea makes up the state's western coast. The capital, Gandhinagar is a planned city. Gujarat has an area of 75,686 sq mi (196,030 km2) with the longest coastline (24% of Indian sea coast) 1,600 km (990 mi), dotted with 41 ports: one major, 11 intermediate and 29 minor.

The Narmada is the largest river in Gujarat followed by the Tapi. The Sabarmati has the longest course through the state. The Sardar Sarovar Project is built on Narmada, one of the major rivers of peninsular India where it is one of only three major rivers that run from east to west – the others being the Tapi and the Mahi. It is about 1,312 km (815 mi) long. Several riverfront embankments have been built on the Sabarmati River.

The eastern borders have fringes of low mountains of India, the Aravalli, Sahyadri (Western Ghats), Vindhya and Saputara. Apart from this the Gir hills, Barda, Jessore and Chotila together make up a large minority of Gujarat. Girnar is the tallest peak and Saputara is the only hill-station (hilltop resort) in the state.

Rann of Kutch

Rann (રણ) is Gujarati for desert. The Rann of Kutch is a seasonally marshy saline clay desert in the Thar Desert biogeographic region between the Pakistani province of Sindh and the rest of the state of Gujarat; it commences 8 km (5.0 mi) from the village of Kharaghoda, Surendranagar District.

Mount Karo, Kutch

Mount Karo, Kutch Cracked earth in the Rann of Kutch

Cracked earth in the Rann of Kutch.jpg.webp) The colourful Rann Utsav Festival is held annually in the Rann of Kutch.

The colourful Rann Utsav Festival is held annually in the Rann of Kutch.

Camel ride in Rann of Kutch

Camel ride in Rann of Kutch

Flora and fauna

Prehistoric fauna

In the early 1980s, palaeontologists found dinosaur egg hatcheries and fossils of at least 13 species in Balasinor.[112] The most important find was that of a carnivorous abelisaurid dinosaur named Rajasurus narmadensis which lived in the Late Cretaceous period.[112][113] A notable discovery in the village of Dholi Dungri was that of Sanajeh indicus, a primitive madtsoiid snake that likely preyed on sauropod dinosaur hatchlings and embryos.[113][114]

Extant species

According to the India State of Forest Report 2011, Gujarat has 9.7% of its total geographical area under forest cover.[115] Among the districts, The Dangs has the largest area under forest cover. Gujarat has four national parks and 21 sanctuaries. It is the only home of Asiatic lions and, outside Africa, is the only present natural habitat of lions.[116] Gir Forest National Park in the southwest part of the state covers part of the lions' habitat. Apart from lions, Indian leopards are also found in the state. They are spread across the large plains of Saurashtra and the mountains of South Gujarat. Other National Parks include Vansda National Park, Blackbuck National Park, Velavadar and Narara Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutchh, Jamnagar. Wildlife sanctuaries include Wild Ass Wildlife Sanctuary, Nal Sarovar Bird Sanctuary, Porbandar Bird Sanctuary, Kutch Desert Wildlife Sanctuary, Kutch Bustard Sanctuary, Narayan Sarovar Sanctuary, Jessore Sloth Bear Sanctuary, Anjal, Balaram-Ambaji, Barda, Jambughoda, Khavda, Paniya, Purna, Rampura, Ratan Mahal, and Surpaneshwar.

In February 2019, a Bengal tiger claimed to be from Ratapani in Madhya Pradesh was spotted in the area of Lunavada in Mahisagar district, in the eastern part of the state,[117][118] before being found dead later that month, likely from starvation.[119]

An Asiatic lion family, which occurs in and around Gir National Park

An Asiatic lion family, which occurs in and around Gir National Park

.jpg.webp)

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 9,094,748 | — |

| 1911 | 9,803,587 | +7.8% |

| 1921 | 10,174,989 | +3.8% |

| 1931 | 11,489,828 | +12.9% |

| 1941 | 13,701,551 | +19.2% |

| 1951 | 16,263,000 | +18.7% |

| 1961 | 20,633,000 | +26.9% |

| 1971 | 26,697,000 | +29.4% |

| 1981 | 34,086,000 | +27.7% |

| 1991 | 41,310,000 | +21.2% |

| 2001 | 50,671,000 | +22.7% |

| 2011 | 60,383,628 | +19.2% |

| Source: Census of India[120] | ||

The population of Gujarat was 60,439,692 (31,491,260 males and 28,948,432 females) according to the 2011 census data.[121] The population density is 308 persons per square kilometre (800 persons/sq mi), lower than other Indian states. As per the census of 2011, the state has a sex ratio of 918 females for every 1000 males, one of the lowest (ranked 24) among the 29 states in India.

While Gujarati speakers constitute a majority of Gujarat's population, the metropolitan areas of Ahmedabad, Vadodara and Surat are cosmopolitan, with numerous other ethnic and language groups. Marwaris compose large minorities of economic migrants; smaller communities of people from the other states of India have also migrated to Gujarat for employment. Luso-Indians, Anglo-Indians, Jews and Parsis also live in the areas.[122] Sindhi presence is traditionally important here following the Partition of India in 1947.[123] The Koli forms the largest caste-cluster, comprising 24% of the total population of the state.[124][125]

Religion

According to 2011 census, the religious makeup in Gujarat was 88.57% Hindu, 9.67% Muslim, 0.96% Jain, 0.52% Christian, 0.10% Sikh, 0.05% Buddhist and 0.03% others. Around 0.1% did not state any religion.[126] Hinduism is the majority religion, and is over 93% in rural areas. Muslims are the biggest minority in the state accounting for 9.7% of the population. Gujarat has the third-largest population of Jains in India, following Maharashtra and Rajasthan, almost all of whom live in urban areas like Vadodara, Ahmedabad and Surat.[127]

The Zoroastrians, also known in India as Parsi and Irani, migrated to Gujarat as refugees. They have also played an instrumental role in economic development, with several of the best-known business conglomerates of India run by Parsi-Zoroastrians, including the Tata, Godrej, and Wadia families. There is a small Jewish community centred around Magen Abraham Synagogue.

Modhera Sun Temple built by Bhimdev

Modhera Sun Temple built by Bhimdev Gurudwara Govinddham, Ahmedabad

Gurudwara Govinddham, Ahmedabad Magen Abraham Jewish Synagogue

Magen Abraham Jewish Synagogue Jama Masjid (Friday Mosque, 15th century), Ahmedabad

Jama Masjid (Friday Mosque, 15th century), Ahmedabad

Language

Gujarati is the official language of the state. It is spoken natively by 86% of the state's population, or 52 million people (as of 2011). Hindi is the second-largest language, spoken by over 6% of the population. Marathi is also spoken in urban areas.[128]

People from the Kutch region of Gujarat also speak in the Kutchi mother tongue, and to a great extent understand Sindhi as well. Memoni is the mother tongue of Kathiawar and Sindhi Memons, most whom are Muslims.

Almost 88% of the Gujarati Muslims speak Gujarati as their mother tongue, whilst the other 12% speak Urdu. A sizeable proportion of Gujarati Muslims are bilingual in the two languages; Islamic academic institutions (Darul Uloom) place a high prestige on learning Urdu and Arabic, with students' memorising the Quran and ahadith, and emphasising the oral and literary importance of mastering these languages as a compulsory rite of religion.

In rural areas among the tribals, various Bhil dialects are spoken by around 1.37% of the population. In the northeast, Bhili is spoken, in the central part is spoken Bhili, Bhilali and Vasava, while in the southeast is spoken Dangi, Varli Chodri and Dhodia which are related to Marathi.

Apart from this, English, Bengali, Kannada, Malayalam, Marwari, Odia, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu and others are spoken by a considerable number of economic migrants from other states of India seeking employment.[129]

The languages taught in schools under the three-language formula are:[130]

First language: Gujarati/Hindi/English

Second language: Gujarati/English

Third language: Hindi

Governance and administration

"Structurally Gujarat is divided into districts (Zila), Prant (subdivisions), Taluka (blocks) & villages. The state is divided into 33 districts, 122 prants, 248 talukas.[131] There are 08 municipal corporations, 156 municipalities and 14,273 Panchayats, for administrative purposes.'

| India | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gujarat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Districts | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prant (Subdivisions) | Municipal Corporations (Mahanagar Palika) | Municipalities (Nagar Palika) | Town Council (Nagar Panchayat) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taluka (Block/Tehsil) | Wards | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gujarat has 33 districts and 250 talukas.[132][133]

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ahmedabad  Surat |

1 | Ahmedabad | Ahmedabad | 6,357,693 | 11 | Morbi | Morbi | 210,451 |  Vadodara  Rajkot |

| 2 | Surat | Surat | 5,935,000 | 12 | Anand | Anand | 209,410 | ||

| 3 | Vadodara | Vadodara | 4,065,771 | 13 | Mehsana | Mehsana | 190,753 | ||

| 4 | Rajkot | Rajkot | 1,390,640 | 14 | Surendranagar Dudhrej | Surendranagar | 177,851 | ||

| 5 | Bhavnagar | Bhavnagar | 605,882 | 15 | Veraval | Gir Somnath | 171,121 | ||

| 6 | Jamnagar | Jamnagar | 479,920 | 16 | Navsari | Navsari | 171,109 | ||

| 7 | Junagadh | Junagadh | 319,462 | 17 | Bharuch | Bharuch | 169,007 | ||

| 8 | Gandhinagar | Gandhinagar | 292,167 | 18 | Vapi | Valsad | 163,630 | ||

| 9 | Gandhidham | Kutch | 248,705 | 19 | Porbandar | Porbandar | 152,760 | ||

| 10 | Nadiad | Kheda | 225,071 | 20 | Bhuj | Kutch | 148,834 | ||

Gujarat is governed by a Legislative Assembly of 182 members. Members of the Legislative Assembly are elected on the basis of adult suffrage from one of 182 constituencies, of which 13 are reserved for scheduled castes and 27 for scheduled tribes. The term of office for a member of the Legislative Assembly is five years. The Legislative Assembly elects a speaker who presides over the meetings of the legislature. A governor is appointed by the President of India, and is to address the state legislature after every general election and the commencement of each year's first session of the Legislative Assembly. The leader of the majority party or coalition in the legislature (Chief Minister) or his or her designee acts as the Leader of the Legislative Assembly. The administration of the state is led by the Chief Minister.

.jpg.webp)

After the independence of India in 1947, the Indian National Congress (INC) ruled the Bombay State (which included present-day Gujarat and Maharashtra). Congress continued to govern Gujarat after the state's creation in 1960.

During and after India's State of Emergency of 1975–1977, public support for the INC eroded, but it continued to hold government until 1995 with the brief rule of nine months by Janata Morcha. In the 1995 Assembly elections, the Congress lost to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Keshubhai Patel who became the Chief Minister. His government lasted only two years. The fall of that government was provoked by a split in the BJP led by Shankersinh Vaghela. BJP again won election in 1998 with clear majority. In 2001, following the loss of two assembly seats in by-elections, Keshubhai Patel resigned and yielded power to Narendra Modi. BJP retained a majority in the 2002 election, and Narendra Modi remained as Chief Minister. On 1 June 2007, Narendra Modi became the longest serving Chief Minister of Gujarat.[134][135][136] BJP retained the power in subsequent elections in 2007 and 2012 and Narendra Modi continued as the chief minister. After Narendra Modi became the prime minister of India in 2014, Anandiben Patel became the first female chief minister of the state. Vijay Rupani took over as chief minister and Nitin Patel as deputy chief minister on 7 August 2016 after Anandiben Patel resigned earlier on 3 August. Bhupendrabhai Patel became chief minister in September 2021 after the resignation of Vijay Rupani.

The incumbent chief secretary of Gujarat is Raj Kumar[137] and director general of police (DGP) is Vikas Sahay.[138]

Economy

During the British Raj, Gujarati businesses played a major role in enriching the economies of Karachi and Mumbai.[139] Major agricultural produce of the state includes cotton, groundnuts (peanuts), dates, sugar cane, milk and milk products. Industrial products include cement and petrol.[140] Gujarat is ranked number one in the pharmaceutical industry in India, with a 33% share in drug manufacturing and 28% share in drug exports. The state has 130 USFDA certified drug manufacturing facilities. Ahmedabad and Vadodara are considered as pharmaceutical hubs, as there are many big and small pharmaceutical companies established in these cities.[141]

Gujarat has the longest coastline in India (1600 km), and its ports (both private and public sector) handle around 40% of India's ocean cargo, with Mundra Port located in Gulf of Kutch being the largest port of India by cargo handled (144 million tons) due to its favourable location on the westernmost part of India and closeness to global shipping lanes. Gujarat also contributes around 20% share in India's industrial production and merchandise exports. According to a 2009 report on economic freedom by the Cato Institute, Gujarat is the most free state in India (the second one being Tamil Nadu).[142] Reliance Industries operates the oil refinery at Jamnagar, which is the world's largest grass-roots refinery at a single location. The world's largest shipbreaking yard is in Gujarat near Bhavnagar at Alang. India's only Liquid Chemical Port Terminal at Dahej, developed by Gujarat Chemical Port Terminal Co Ltd. Gujarat has two of the three liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals in the country (Dahej and Hazira). Two more LNG terminals are proposed, at Pipavav and Mundra.

Gujarat has 85% village connectivity with all‐weather roads.[143] Nearly 100% of Gujarat's 18,000 villages have been connected to the electrical grid for 24-hour power to households and eight hours of power to farms, through the Jyotigram Yojana.[144] As of 2015, Gujarat ranks first nationwide in gas-based thermal electricity generation with a national market share of over 8%, and second nationwide in nuclear electricity generation with national market share of over 1%.[145]

The state registered 12.8% agricultural growth in the last five years against the national average of 2%.[146]

Gujarat records highest decadal agricultural growth rate of 10.97%. Over 20% of the S&P CNX 500 conglomerates have corporate offices in Gujarat.[147] As per RBI report, in year 2006–07, 26% of total bank finance in India was in Gujarat.

According to a 2012 survey report of the Chandigarh Labour Bureau, Gujarat had the lowest unemployment rate of 1% against the national average of 3.8%.[148]

Legatum Institute's Global Prosperity Index 2012 recognised Gujarat as one of the two highest-scoring among all states of India on matters of social capital.[149] The state ranks 15th alongside Germany in a list of 142 nations worldwide: higher than several developed nations.[150]

Infrastructure

The tallest tower in Gujarat, GIFT One was inaugurated on 10 January 2013. One other tower called GIFT Two has been finished and more towers are planned.[151]

Industrial growth

Gujarat's major cities include Ahmedabad, Surat, Vadodara, Rajkot, Jamnagar and Bhavnagar. In 2010, Forbes' list of the world's fastest growing cities included Ahmedabad at number 3 after Chengdu and Chongqing from China.[152][153] The state is rich in calcite, gypsum, manganese, lignite, bauxite, limestone, agate, feldspar, and quartz sand, and successful mining of these minerals is done in their specified areas. Jamnagar is the hub for manufacturing brass parts. Gujarat produces about 98% of India's required amount of soda ash, and gives the country about 78% of the national requirement of salt. It is one of India's most prosperous states, having a per-capita GDP significantly above India's average. Kalol, Khambhat, and Ankleshwar are today known for their oil and natural gas production. Dhuvaran has a thermal power station, which uses coal, oil, and gas. Also, on the Gulf of Khambhat, 50 km (31 mi) southeast of Bhavnagar, is the Alang Ship Recycling Yard (the world's largest). MG Motor India manufactures its cars at Halol near Vadodara, Tata Motors manufactures the Tata Nano from Sanand near Ahmedabad, and AMW trucks are made near Bhuj. Surat, a city by the Gulf of Khambhat, is a hub of the global diamond trade. In 2003, 92% of the world's diamonds were cut and polished in Surat.[154] The diamond industry employs 500,000 people in Gujarat.[155]

At an investor's summit entitled "Vibrant Gujarat Global Investor Summit", arranged between 11 and 13 January 2015, at Mahatma Mandir, Gandhinagar, the state government signed 21000 Memoranda of Understanding for Special Economic Zones worth a total of ₹ 2.5 million crores (short scale).[156] However, most of the investment was from domestic industry.[157] In the fourth Vibrant Gujarat Global Investors' Summit held at Science City, Ahmedabad, in January 2009, there were 600 foreign delegates. In all, 8668 MOUs worth ₹ 12500 billion were signed, estimated to create 2.5 million new job opportunities in the state.[158] In 2011, Vibrant Gujarat Global Investors' Summit MOUs worth ₹ 21 trillion (US$ 463 billion) were signed.

Gujarat is a state with surplus electricity.[159] The Kakrapar Atomic Power Station is a nuclear power station run by NPCIL that lies in the proximity of the city of Surat. According to the official sources, against demand of 40,793 million units during the nine months since April 2010, Gujarat produced 43,848 million units. Gujarat sold surplus power to 12 states: Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Haryana, Karnataka, Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal.[160]

Energy

As of April 2022, the peak power requirement of state is 20,277 MW.[162] Total installed power generation capacity is 44,127.43 MW. Of this 25,688.66 MW belongs to thermal power generation capacity while 17,879.77 MW belongs to renewable energy generation capacity. The rest 559 MW is nuclear power generation capacity.[163] The renewable energy installed capacity includes 9,209 MW wind power and 7,180 MW solar power, as of March 2022.[164]

Agriculture

The total geographical area of Gujarat is 19,602,400 hectares, of which crops take up 10,630,700 hectares.[165] The three main sources of growth in Gujarat's agriculture are from cotton production, the rapid growth of high-value foods such as livestock, fruits and vegetables, and from wheat production, which saw an annual average growth rate of 28% between 2000 and 2008 (According to the International Food Policy Research Institute).[166] Other major produce includes bajra, groundnut, cotton, rice, maize, wheat, mustard, sesame, pigeon pea, green gram, sugarcane, mango, banana, sapota, lime, guava, tomato, potato, onion, cumin, garlic, isabgul and fennel. Whilst, in recent times, Gujarat has seen a high average annual growth of 9% in the agricultural sector, the rest of India has an annual growth rate of around 3%. This success was lauded by former President of India, APJ Abdul Kalam.[167]

The strengths of Gujarat's agricultural success have been attributed to diversified crops and cropping patters; climatic diversity (8 climatic zones for agriculture); the existence of 4 agricultural universities in the state, which promote research in agricultural efficiency and sustainability;[168] co-operatives; adoption of hi-tech agriculture such as tissue culture, green houses and shed-net houses; agriculture export zones; strong marketing infrastructure, which includes cold storage, processing units, logistic hubs and consultancy facilities.[169]

Gujarat is the main producer of tobacco, cotton, and groundnuts in India. Other major food crops produced are rice, wheat, jowar, bajra, maize, tur, and gram. The state has an agricultural economy; the total crop area amounts to more than one-half of the total land area.[170]

Animal husbandry and dairying have played vital roles in the rural economy of Gujarat. Dairy farming, primarily concerned with milk production, functions on a co-operative basis and has more than a million members. Gujarat is the largest producer of milk in India. The Amul milk co-operative federation is well known all over India, and it is Asia's biggest dairy.[171] Among the livestock raised are, buffaloes and other cattle, sheep, and goats. As per the results of livestock census 1997, there were 20.97 million head of livestock in Gujarat State. In the estimates of the survey of major livestock products, during the year 2002–03, Gujarat produced 6.09 million tonnes of milk, 385 million eggs and 2.71 million kg of wool. Gujarat also contributes inputs to the textiles, oil, and soap industries.

The adoption of cooperatives in Gujarat is widely attributed to much of the success in the agricultural sector, particularly sugar and dairy cooperatives. Cooperative farming has been a component of India's strategy for agricultural development since 1951. Whilst the success of these was mixed throughout the country, their positive impact on the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat have been the most significant. In 1995 alone, the two states had more registered co-operatives than any other region in the country. Out of these, the agricultural cooperatives have received much attention. Many have focused on subsidies and credit to farmers and rather than collective gathering, they have focused on facilitating collective processing and marketing of produce. However, whilst they have led to increased productivity, their effect on equity in the region has been questioned, because membership in agricultural co-operatives has tended to favour landowners whilst limiting the entry of landless agricultural labourers.[172] An example of co-operative success in Gujarat can be illustrated through dairy co-operatives, with the particular example of Amul (Anand Milk Union Limited).

Amul was formed as a dairy cooperative in 1946,[173] in the city of Anand, Gujarat. The cooperative, Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation Ltd. (GCMMF), is jointly owned by around 2.6 million milk producers in Gujarat. Amul has been seen as one of the best examples of cooperative achievement and success in a developing economy and the Amul pattern of growth has been taken as a model for rural development, particularly in the agricultural sector of developing economies. The company stirred the White Revolution of India (also known as Operation Flood), the world's biggest dairy development program, and made the milk-deficient nation of India the largest milk producer in the world, in 2010.[174] The "Amul Model" aims to stop the exploitation by middlemen and encourage freedom of movement since the farmers are in control of procurement, processing and packaging of the milk and milk products.[175] The company is worth 2.5 billion US dollars (as of 2012).[176]

70% of Gujarat's area is classified as semi-arid to arid climatically, thus the demand on water from various economic activities puts a strain on the supply.[177] Of the total gross irrigated area, 16–17% is irrigated by government-owned canals and 83–84% by privately owned tube wells and other wells extracting groundwater, which is the predominant source of irrigation and water supply to the agricultural areas. As a result, Gujarat has faced problems with groundwater depletion, especially after demand for water increased in the 1960s. As access to electricity in rural areas increased, submersible electric pumps became more popular in the 1980s and 1990s. However, the Gujarat Electricity Board switched to flat tariff rates linked to the horsepower of pumps, which increased tubewell irrigation again and decreased the use of electric pumps. By the 1990s, groundwater abstraction rates exceeded groundwater recharge rate in many districts, whilst only 37.5% of all districts has "safe" recharge rates. Groundwater maintenance and preventing unnecessary loss of the available water supplies is now an issue faced by the state.[178] The Sardar Sarovar Project, a debated dam project in the Narmada valley consisting of a network of canals, has significantly increased irrigation in the region. However, its impact on communities who were displaced is still a contested issue. In 2012 Gujarat began an experiment to reduce water loss due to evaporation in canals and to increase sustainability in the area, by constructing solar panels over the canals. In a one megawatt (MW) solar power project set up at Chandrasan, Gujarat uses solar panels fixed over a 750-metre stretch of an irrigation canal. Unlike many solar power projects, this one does not take up large amounts of land since the panels are constructed over the canals, and not on additional land. This results in lower upfront costs since land does not need to be acquired, cleared or modified to set up the panels. The Chandrasan project is projected to save 9 million litres of water per year.[179]

The Government of Gujarat, to improve soil management and introduce farmers to new technology, started on a project which involved giving every farmer a Soil Health Card. This acts like a ration card, providing permanent identification for the status of cultivated land, as well as farmers' names, account numbers, survey numbers, soil fertility status and general fertiliser dose. Samples of land from each village are taken and analysed by the Gujarat Narmada Valley Fertiliser Corporation, State Fertiliser Corporation and Indian Farmers Fertilisers Co-operative. 1,200,000 soil test data from the villages was collected as of 2008, from farmer's field villages have gone into a database. Assistance and advice for this project was given by local agricultural universities and crop and soil-specific data was added to the database. This allows the soil test data to be interpreted and recommendations or adjustments made in terms of fertiliser requirements, which are also added to the database.[180]

Culture

Gujarat is home for the Gujarati people. Gujarat was also the home of Mahatma Gandhi, a worldwide figure known for his non-violent struggle against British rule, and Vallabhbhai Patel, a founding father of the Republic of India.

Literature

The history of Gujarati literature may be traced back to 1000 CE. Well-known laureates of Gujarati literature include Hemchandracharya, Narsinh Mehta, Mirabai, Akho, Premanand Bhatt, Shamal Bhatt, Dayaram, Dalpatram, Narmad, Govardhanram Tripathi, Mahatma Gandhi, K. M. Munshi, Umashankar Joshi, Suresh Joshi, Swaminarayan, Pannalal Patel and Rajendra Shah.[181]

Kavi Kant, Zaverchand Meghani and Kalapi are famous Gujarati poets.

Gujarat Vidhya Sabha, Gujarat Sahitya Sabha, and Gujarati Sahitya Parishad are Ahmedabad based literary institutions promoting the spread of Gujarati literature. Saraswatichandra is a landmark novel by Govardhanram Tripathi. Writers like Aanand Shankar Dhruv, Ashvini Bhatt, Balwantray Thakore, Bhaven Kachhi, Bhagwatikumar Sharma, Chandrakant Bakshi, Gunvant Shah, Harindra Dave, Harkisan Mehta, Jay Vasavada, Jyotindra Dave, Kanti Bhatt, Kavi Nanalal, Khabardar, Sundaram, Makarand Dave, Ramesh Parekh, Suresh Dalal, Tarak Mehta, Vinod Bhatt, Dhruv Bhatt and Varsha Adalja have influenced Gujarati thinkers.

A notable contribution to Gujarati literature came from the Swaminarayan paramhanso, like Brahmanand Swami, Premanand, with prose like Vachanamrut and poetry in the form of bhajans.[182]

Shrimad Rajchandra Vachnamrut and Shri Atma Siddhi Shastra, written in 19th century by Jain philosopher and poet Shrimad Rajchandra (Mahatma Gandhi's guru) are very well known.[183][184]

Gujarati theatre owes a lot to Bhavai. Bhavai is a folk musical performance of stage plays. Ketan Mehta and Sanjay Leela Bhansali explored artistic use of bhavai in films such as Bhavni Bhavai, Oh Darling! Yeh Hai India and Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam. Dayro (gathering) involves singing and conversation reflecting on human nature.

Mumbai theatre veteran, Alyque Padamsee, best known in the English-speaking world for playing Muhammad Ali Jinnah in Sir Richard Attenborough's Gandhi, was from a traditional Gujarati-Kutchi family from Kathiawar.[185]

Cuisine

Gujarati food is primarily vegetarian. The typical Gujarati thali consists of rotli or bhakhari or thepala or rotlo, dal or kadhi, khichdi, Bhat and shak. Athanu (Indian pickle) and chhundo are used as condiments. The four major regions of Gujarat all bring their own styles to Gujarati food. Many Gujarati dishes are distinctively sweet, salty, and spicy at the same time. In the Saurashtra region, chhash (buttermilk) is believed to be a must-have in their daily food.

Cinema

The Gujarati film industry dates back to 1932, when the first Gujarati film, Narsinh Mehta, was released.[186][187][188] After flourishing through the 1960s to 1980s, the industry saw a decline. The industry is revived in recent times. The film industry has produced more than one thousand films since its inception.[189] The Government of Gujarat announced a 100% entertainment tax exemption for Gujarati films in 2005[190] and a policy of incentives in 2016.[191]

Music

Gujarati folk music, known as Sugam Sangeet, is a hereditary profession of the Barot community. Gadhvi and Charan communities have contributed heavily in modern times. The omnipresent instruments in Gujarati folk music include wind instruments, such as turi, bungal, and pava, string instruments, such as the ravan hattho, ektaro, and jantar and percussion instruments, such as the manjira and zanz pot drum.[192]

Festivals

Navratri Garba at Ambaji temple

Navratri Garba at Ambaji temple Tourists playing Dandiya Raas

Tourists playing Dandiya Raas International Kite Festival, Ahmedabad

International Kite Festival, Ahmedabad

The folk traditions of Gujarat include bhavai and raas-garba. Bhavai is a folk theatre; it is partly entertainment and partly ritual, and is dedicated to Amba. The raas-garba is a folk dance done as a celebration of Navratri by Gujarati people. The folk costume of this dance is chaniya choli for women and kedia for men. Different styles and steps of garba include dodhiyu, simple five, simple seven, popatiyu, trikoniya (hand movement which forms an imagery triangle), lehree, tran taali, butterfly, hudo, two claps and many more. Sheri garba is one of the oldest form of garba where all the women wear red patola sari and sing along while dancing. It is a very graceful form of garba.[193] Makar Sankranti is a festival where people of Gujarat fly kites. In Gujarat, from December through to Makar Sankranti, people start enjoying kite flying. Undhiyu, a special dish made of various vegetables, is a must-have of Gujarati people on Makar Sankranti. Surat is especially well known for the strong string which is made by applying glass powder on the row thread to provide it a cutting edge.[194]

Apart from Navratri and Uttarayana, Diwali, Holi, Janmashtami, Mahavir Janma Kalyanak, Eid, Tazia, Paryushan and others are also celebrated.

Diffusion of culture

Due to close proximity to the Arabian Sea, Gujarat has developed a mercantile ethos which maintained a cultural tradition of seafaring, long-distance trade, and overseas contacts with the outside world since ancient times, and the diffusion of culture through Gujarati diaspora was a logical outcome of such a tradition. During the pre-modern period, various European sources have observed that these merchants formed diaspora communities outside of Gujarat, and in many parts of the world, such as the Persian Gulf, Middle East, Horn of Africa, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and Philippines.[195] long before the internal rise of the Maratha dynasty, and the British Raj colonial occupation.[196]

Early 1st-century Western historians such as Strabo and Dio Cassius are testament to Gujarati people's role in the spread of Buddhism in the Mediterranean, when it was recorded that the sramana monk Zarmanochegas (Ζαρμανοχηγὰς) of Barygaza met Nicholas of Damascus in Antioch while Augustus ruled the Roman Empire, and shortly thereafter proceeded to Athens where died by setting himself on fire to demonstrate his faith.[197][198] A tomb to the sramana, was still visible in the time of Plutarch,[199] which bore the mention "ΖΑΡΜΑΝΟΧΗΓΑΣ ΙΝΔΟΣ ΑΠΟ ΒΑΡΓΟΣΗΣ" ("The sramana master from Barygaza in India").[200]

The progenitor of the Sinhala language is believed to have been Prince Vijaya, son of King Simhabahu, who ruled Simhapura (modern-day Sihor near Bhavnagar).[201] Prince Vijaya was banished by his father for his lawlessness and set forth with a band of adventurers. This tradition was followed by other Gujaratis. For example, in the Ajanta frescoes, a Gujarati prince is shown entering Sri Lanka.[202]

Many Indians migrated to Indonesia and the Philippines, most of them Gujaratis. King Aji Saka, who is said to have come to Java in Indonesia in year 1 of the Saka calendar, is believed by some to have been a king of Gujarat.[203] The first Indian settlements in the Philippines and Java Island of Indonesia are believed to have been established with the coming of Prince Dhruvavijaya of Gujarat, with 5000 traders.[203] Some stories propose a Brahmin named Tritresta was the first to bring Gujarati migrants with him to Java, so some scholars equate him with Aji Saka.[204] A Gujarati ship has been depicted in a sculpture at Borabudur, Java.[202]

Tourism

.jpg.webp)

Gujarat's natural environment includes the Great Rann of Kutch and the hills of Saputara, and it is the sole home of pure Asiatic lions in the world.[205] During the historic reigns of the sultans, Hindu craftsmanship blended with Islamic architecture, giving rise to the Indo-Saracenic style. Many structures in the state are built in this fashion. It is also the birthplace of Mahatma Gandhi and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, great iconic figures of India's Independence movement. Amitabh Bachchan is currently the brand ambassador of Gujarat Tourism.[206]

Museums and memorials

Gujarat has a variety of museums on different genres that are run by the state's Department of Museums located at the principal state museum, Baroda Museum & Picture Gallery in Vadodara,[207] which is also the location of the Maharaja Fateh Singh Museum. The Kirti Mandir, Porbandar, Sabarmati Ashram, and Kaba Gandhi No Delo are museums related to Mahatma Gandhi, the former being the place of his birth and the latter two where he lived in his lifetime. Kaba Gandhi No Delo in Rajkot exhibits part of a rare collection of photographs relating to the life of Mahatma Gandhi. Sabarmati Ashram is the place where Gandhi initiated the Dandi March. On 12 March 1930 he vowed that he would not return to the Ashram until India won independence.[208]

The Maharaja Fateh Singh Museum is housed within Lakshmi Vilas Palace, the residence of the erstwhile Maharajas, located in Vadodara.

The Calico Museum of Textiles is managed by the Sarabhai Foundation and is one of the most popular tourist spots in Ahmedabad.

The Lakhota Museum at Jamnagar is a palace transformed into museum, which was residence of the Jadeja Rajputs. The collection of the museum includes artefacts spanning from 9th to 18th centuries, pottery from medieval villages nearby and the skeleton of a whale.

Other well-known museums in the state include the Kutch Museum in Bhuj, which is the oldest museum in Gujarat founded in 1877, the Watson Museum of human history and culture in Rajkot,[209] Gujarat Science City and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Memorial in Ahmedabad. In October 2018, the world's tallest statue commemorating the independence leader Sardar Patel was unveiled. At 182 metres tall the Statue of Unity is the newest tourist attraction with over 30,000 visitors every day.[210][211]

Religious sites

Religious sites play a major part in the tourism of Gujarat. Somnath is the first of the twelve Jyotirlingas, and is mentioned in the Rigveda. The Dwarakadheesh Temple, Radha Damodar Temple, Junagadh and Dakor are holy pilgrimage sites with temples dedicated to Lord Krishna. The Sun Temple, Modhera is a ticketed monument, handled by the Archaeological Survey of India.[212] Other religious sites in state include Ambaji, Dakor, Shamlaji, Chotila, Becharaji, Mahudi, Shankheshwar etc. The Palitana temples of Jainism on Mount Shatrunjaya, Palitana are considered the holiest of all pilgrimage places by the Svetambara and Digambara Jain community.[213] Palitana is the world's only mountain with more than 900 temples.[214] The Sidi Saiyyed Mosque and Jama Masjid are holy mosques for Gujarati Muslims.

Fairs

A five-day festival is held during Maha Shivaratri at the fort of Girnar, Junagadh, known as the Bhavanth Mahadev Fair (Gujarati: ભવનાથ નો મેળો). The Kutch Festival or Rann Festival (Gujarati: કચ્છ or રણ ઉત્સવ) is a festival celebrated at Kutch during Mahashivratri. The Modhra Dance Festival is a festival for classical dance, arranged by the Government of Gujarat's Cultural Department, to promote tourism in state and to keep traditions and culture alive.[215]

The Ambaji Fair is held in the Hindu month of Bhadrapad (around August–September) at Ambaji, during a time which is particularly suitable for farmers, when the busy monsoon season is about to end. The Bhadrapad fair is held at Ambaji which is in the Danta Taluka of Banaskantha district, near the Gujarat-Rajasthan border. The walk from the bus station to the temple is less than one kilometre, under a roofed walkway. Direct buses are available from many places, including Mount Abu (45 km away), Palanpur (65 km away), Ahmedabad and Idar. The Bhadrapad fair is held in the centre of the Ambaji village just outside the temple premises. The village is visited by the largest number of sanghas (pilgrim groups) during the fair. Many of them go there on foot, which is particularly enriching as it happens immediately after the monsoon, when the landscape is rich with greenery, streams are full of sparkling water and the air is fresh. About 1.5 million devotees are known to attend this fair each year from all over the world. Not only Hindus, but some devout Jains and Parsis also attend the functions, whilst some Muslims attend the fair for trade.

The Tarnetar Fair is held during the first week of Bhadrapad, (September–October according to Gregorian calendar), and mostly serves as a place to find a suitable bride for tribal people from Gujarat. The region is believed to be the place where Arjuna took up the difficult task of piercing the eye of a fish, rotating at the end of a pole, by looking at its reflection in the pond water, to marry Draupadi.[216] Other fairs in Gujarat include Dang Durbar, Shamlaji Fair, Chitra Vichitra Fair, Dhrang Fair and Vautha Fair.

The Government of Gujarat has banned alcohol since 1960.[217] Gujarat government collected the Best State Award for 'Citizen Security' by IBN7 Diamond States on 24 December 2012.[218]

Transport

Air

There are three international airports (Ahmedabad and Surat, Vadodara), nine domestic airports (Bhavnagar, Bhuj, Jamnagar, Kandla, Porbandar, Rajkot, Amreli, Keshod), two private airports (Mundra, Mithapur) and three military bases (Bhuj, Jamnagar, Naliya) in Gujarat. Two more airports (Ankleshwar, Rajkot) are under construction. There are three disused airports situated at Deesa, Mandvi and Mehsana; the last serving as a flying school. Gujarat State Aviation Infrastructure Company Limited (GUJSAIL) has been established by the Government of Gujarat to foster development of aviation infrastructure in the state.[219]

These airports are operated and owned by either the Airports Authority of India, Indian Air Force, Government of Gujarat or private companies.[220][221]

Rail

Gujarat comes under the Western Railway Zone of the Indian Railways. Ahmedabad Railway Station is the most important, centrally located and biggest railway station in Gujarat which connects to all important cities of Gujarat and India.Surat railway station and Vadodara Railway Station is also the busiest railway station in Gujarat and the ninth busiest railway station in India. Other important railway stations are Palanpur Junction, Bhavnagar Terminus, Rajkot Railway Station, Sabarmati Junction, Nadiad Junction, Valsad Railway Station, Bharuch Junction, Gandhidham Junction, Anand Junction, Godhra Railway Station, etc. Indian Railways is planning a dedicated rail freight route Delhi–Mumbai passing through the state.

The 39.259 km (24.394 mi) long tracks of the first phase of MEGA, a metro rail system for Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar is under construction. It is expected to complete by 2024. The construction started on 14 March 2015.[222][223]

Sea

Gujarat State has the longest sea coast of 1214 km in India. Kandla Port is one of the largest ports serving Western India. Other important ports in Gujarat are the Port of Navlakhi, Port of Magdalla, Port Pipavav, Bedi Port, Port of Porbandar, Port of Veraval and the privately owned Mundra Port. The state also has Ro-Ro ferry service.[224]

Road

Gujarat State Road Transport Corporation (GSRTC) is the primary body responsible for providing the bus services within the state of Gujarat and also with the neighbouring states. It is a public transport corporation providing bus services and public transit within Gujarat and to the other states in India. Apart from this, there are a number of services provided by GSRTC.

- Mofussil Services – connects major cities, smaller towns and villages within Gujarat.[225]

- Intercity Bus Services – connects major cities – Ahmedabad, Surat, Veraval, Vapi, Vadodara (Baroda), Rajkot, Bharuch etc.[225]

- Interstate Bus Services – connects various cities of Gujarat with the neighbouring states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan.[225]

- City Services – GSRTC provides city bus services at Surat, Vadodara, Vapi, Gandhinagar and Ahmedabad, within the state of Gujarat.[225]

- Parcel Services – service used for transporting goods.[225]

Apart from this, the GSRTC provides special bus services for festivals, industrial zones, schools, colleges and pilgrim places also buses are given on contract basis to the public for certain special occasions.[225]

- There are also city buses in cities like Ahmedabad (AMTS and Ahmedabad BRTS), Surat (Surat BRTS), Bhavnagar (BMC CITY BUS) ) Vadodara (Vinayak Logistics), Gandhinagar (VTCOS), Rajkot (RMTS and Rajkot BRTS), Anand (VTCOS) Bharuch (Gurukrupa) etc.

Auto rickshaws are common mode of transport in Gujarat. The Government of Gujarat is promoting bicycles to reduce pollution by the way of initiative taken by free cycle rides for commuters..

Education and research

The Gujarat Secondary and Higher Secondary Education Board (GSHSEB) are in charge of the schools run by the Government of Gujarat. However, most of the private schools in Gujarat are affiliated to the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) and Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE) board. Gujarat has 13 state universities and four agricultural universities.

Institutes for Engineering and Research in the area include IIT Gandhinagar, Indian Institute of Information Technology Vadodara (IIITV), Institute of Infrastructure Technology Research and Management (IITRAM), Dhirubhai Ambani Institute of Information and Communication Technology (DA-IICT) also in Gandhinagar, Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology (SVNIT) and P P Savani University in Surat, Pandit Deendayal Petroleum University (PDPU) in Gandhinagar, Nirma University in Ahmedabad, M.S. University in Vadodara, Marwadi Education Foundation's Group of Institutions (MEFGI) in Rajkot and Birla Vishwakarma Mahavidyalaya (BVM) in Vallabh Vidyanagar (a suburb in Anand district).

Mudra Institute of Communications Ahmedabad (MICA) is an institute for mass communication.

In addition, Institute of Rural Management Anand (IRMA) is one of the leading sectoral institution in rural management. IRMA is a unique institution in the sense that it provides professional education to train managers for rural management. It is the only one of its kind in all Asia.

The National Institute of Design and development (NID) in Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar is internationally acclaimed as one of the foremost multi-disciplinary institutions in the field of design education and research. Centre for Environmental Planning & Technology University, popularly known as (CEPT) is one of the best planning and architectural school not in India, but across the world; providing various technical and professional courses.